Abstract

Ultrasound (US) is the most commonly used imaging method for studying urinary tract disorders in dogs, as it is easy to perform, inexpensive and provides excellent contrast resolution in real-time. However, US examination of dogs presents a series of technical difficulties, and the US operator must therefore have a longstanding experience and access to high-quality equipment including a range of different probes to achieve a correct diagnosis. The aim of this mini-pictorial essay is to describe US findings and patterns which permit identification of the most common pathologies of the urinary tract in dogs. The technical difficulties that may be encountered are also evaluated as well as integration with other imaging modalities (traditional X-ray, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging).

Keywords: Ultrasound, Canine pathology, Urinary system, Sonography

Riassunto

L’ecografia è la metodica di imaging più utilizzata per lo studio dell’apparato urinario del cane per varie ragioni: la semplicità di utilizzo, i costi ridotti, la possibilità di avere un esame in tempo reale e l’ottima risoluzione spaziale. L’ecografia del cane presenta, tuttavia, una serie di difficoltà tecniche che rendono necessario acquisire un’esperienza significativa e disporre di uno strumentario completo, di qualità elevata, per ottenere i risultati aspettati. Questo mini-pictorial essay si propone di fornire un riferimento iconografico minimo, ma completo, per individuare le patologie più frequenti dell’apparato urinario del cane, oltre a valutare le difficoltà tecniche che si possono incontrare e le integrazioni con le altre metodiche di imaging (radiografia tradizionale, tomografia computerizzata, risonanza magnetica).

Introduction

Ultrasound (US) is the most commonly used imaging method for studying urinary tract disorders in dogs, as it is easy to perform, inexpensive and provides excellent contrast resolution in real-time. When combined with direct abdominal X-ray, US is usually able to provide a definitive diagnosis, and few situations require further investigation using other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. US is furthermore useful for guiding interventional procedures [1].

However, US examination presents a series of technical difficulties in dogs, and the US operator must therefore have a significant experience and access to US equipment of high quality to achieve a correct diagnosis. Some of the difficulties in question are encountered in the US study of all the anatomical structures of the dog, while others are specific to the urinary tract.

Dogs vary considerably in size, and probes suitable for different situations are therefore required as well as disposable or reusable standoff pads to be applied to the probes. Shaving of the dog’s fur is time-consuming and may prevent the decision to evaluate contralateral structures, particularly if not foreseen before the examination, as contralateral shaving is difficult during the examination. The psychological aspect of shaving should furthermore not be underestimated, as it may be seen as defacement, albeit minimal, both by the owner and the animal itself.

In most dogs, the urinary system contains little adipose tissue and the contrast between the different planes and anatomical structures is therefore poor. Moreover, while most US examinations (e.g. of the musculoskeletal system) can be performed without deep sedation of the dog, examination of the urinary system may be more difficult. The position and possible pain may cause the animal to be intractable and as reported in the literature, sedation/anesthesia may be required. However, the benefits of performing the examination under sedation/anesthesia should always be weighed up against the risk and cost involved as well as the need to minimize the duration of the procedure.

On contrary to the literature, in our experience, sedation is required only in a limited number of cases, i.e. no more than 10 %.

Despite the crucial role of US and wide diffusion among veterinarians, it seems that not all veterinarian US operators possess the necessary experience which enables them to quickly identify pathological US findings. The aim of this mini-pictorial essay is to describe US findings and patterns which permit identification of the most common pathologies of the urinary tract in dogs.

US aspects of urinary tract disorders in dogs

Bladder

The urinary tract disease which most frequently affects dogs is undoubtedly urolithiasis [2]. The presence of calculi particularly in the bladder can be easily diagnosed at US imaging (Figs. 1, 2). Bladder stones appear as multiple (Fig. 1) or individual (Fig. 2) hyperechoic formations with posterior acoustic shadowing artifacts. They move within the bladder lumen according to the position due to gravity (Fig. 2) and may be associated with bladder wall thickening. Occasionally, the bladder wall may not be visible due to shadow cone artifacts and the possible coexistence of a neoplastic disease; in that case US-guided cystocentesis may be required (Fig. 3).

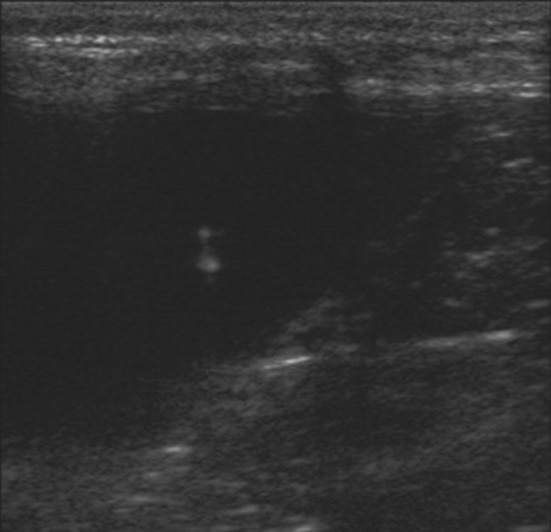

Fig. 1.

Pug dog with hematuria. US imaging shows multiple debris in the lumen of the bladder and moderate bladder wall thickening. Cystocentesis revealed no malignant cells

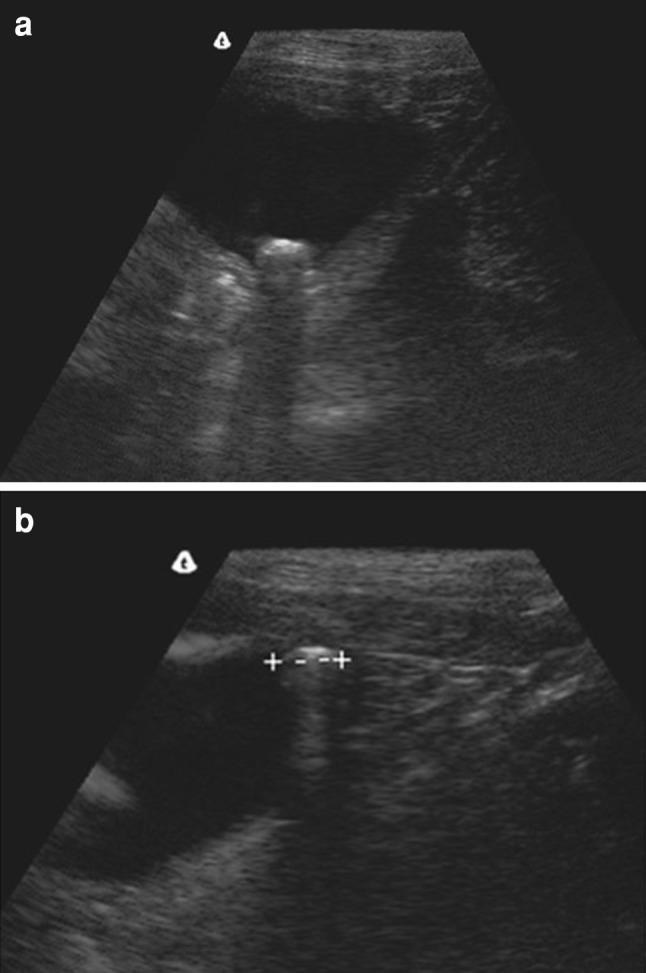

Fig. 2.

A 7-year-old wolfdog weighing 10 kg, with hematuria. US imaging shows bladder stone which is hyperechoic with posterior acoustic shadowing (a); the stone moves according to the dog’s position (b)

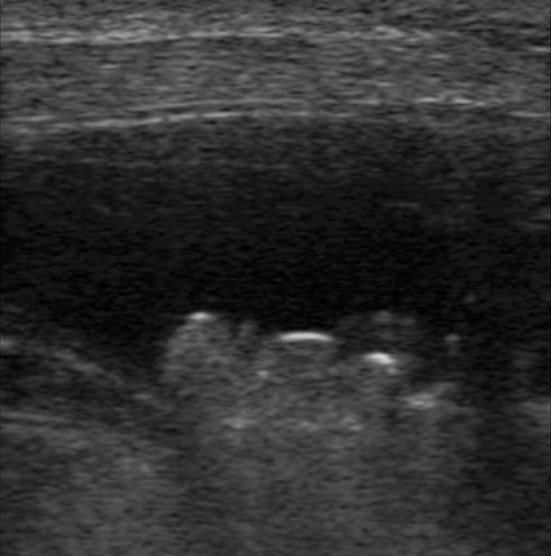

Fig. 3.

Pug dog with hematuria. US imaging shows abundant debris in the bladder, partly adherent to the wall. The examination does not rule out underlying bladder cancer. Surgical findings: calculosi concrementi, cystitis, non-neoplastic cells

It should be kept in mind that spatial compound imaging reduces artifacts and improves image quality by reducing the background noise; the posterior shadow cone is attenuated and may almost disappear. Spatial compound imaging thus changes the traditional US patterns but this technique improves the ability to identify pathologies of the bladder wall and may therefore be useful in cases of doubt [3].

Even though US imaging provides important diagnostic information in real-time, plain abdominal X-ray is required to determine the composition of the urinary calculi [4]. US cannot identify the composition, which is essential for a correct therapeutic planning. Radiographic features such as radiopacity, morphology, number and dimensions of the calculi can provide a fairly reliable identification of the chemical composition. Plain abdominal X-ray is also required in the follow-up after lithotripsy [5].

Prostate

Canine prostate diseases are very similar to those of humans. Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is very common among dogs, as 80 % of unneutered dogs over 5-year old have BPH [6]. Surface US allows assessment of the volume and shows US appearance of the gland. Physiological prostatic volume can be calculated according to a formula based on the dog’s weight and age [7] and be compared to the volume actually found, based on US measurements (craniocaudal extension and maximum axial diameter) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

An 8-year-old St. Bernard dog weighing 40 kg, with acute urinary retention. US shows enlarged prostate with prostatic cyst

The echostructure is also very important [6–8]: under normal circumstances the prostate is homogeneously echoic, whereas it is widely inhomogeneous when affected by BPH. Unlike the human prostate, the canine prostate affected by BPH is furthermore characterized by cystic degeneration. These prostatic cysts are classified as retention cysts (intraparenchymal and typically linked to BPH) or paraprostatic cysts (outside the gland and unrelated to BPH); US differential diagnosis is simple and prompt [8] (Fig. 4). US is also essential for guiding biopsy procedures required to exclude prostate cancer or to drain prostatic cysts [7].

Kidneys

One of the most frequent disorders diagnosed at US imaging of the kidney is hydroureteronephrosis (Fig. 5). Various conditions can cause hydroureteronephrosis and some of them can be identified at US examination. However, in the presence of hydroureteronephrosis, the US operator should first of all suspect possible coexistence of pyonephrosis [9]. Pyonephrosis is an infection of the pyelic cavity which can be caused by an ascending infection or as a complication of nephritis. Prognosis is generally poor and death may occur. US differential diagnosis is difficult, but the presence of hyperechoic spots in the area of hydroureteronephrosis suggests pyonephrosis. The hyperechoic spots are caused by cell debris which makes the contents of the pyelic cavity appear inhomogeneous, and sometimes fluid-debris levels are present [9]. In the presence of inhomogeneous contents in the pyelic cavity, CT or MR imaging should always be performed, as US alone is often unable to provide a correct diagnosis [10].

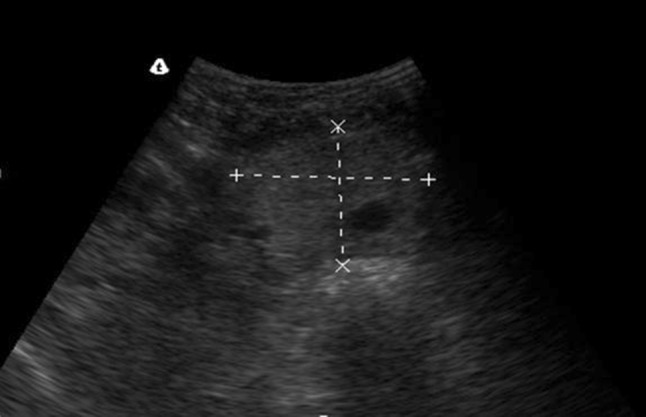

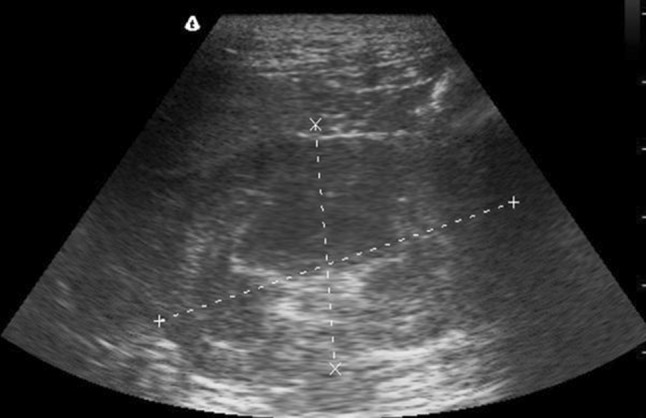

Fig. 5.

Wolf dog with abdominal pain on the left side and positive urine culture. US imaging shows kidney with slight loss of the outer cortical layer and urine stasis

US is useful in renal pathologies, not only in the diagnostic phase but also for guiding drainage and local administration of antibiotics [11]. Also less frequent pathologies such as neoplastic diseases can be identified by US, but a definitive diagnosis often requires CT and biopsy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, US is an essential imaging tool for studying the urinary tract in dogs. However, there are also some limitations linked to this method. The advantages are the wide diffusion of the method and the fact that it is fast and inexpensive. US also provides the possibility to perform various diagnostic procedures under US guidance (such as cystocentesis) as well as therapeutic procedures (Fig. 6). These procedures may require sedation/anesthesia which is technically simple to administer, but it clearly involves additional costs. The limitations are linked to the duration of the examination when sedation/anesthesia is required and to the narrow acoustic window which is limited to the area which has been shaved, thus not allowing an extended field of view.

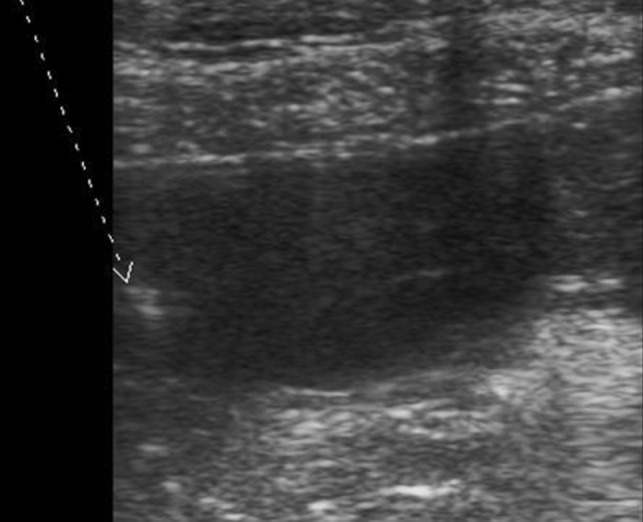

Fig. 6.

Same case as Fig. 5; US-guided cystocentesis. US allows the operator to visualize the needle tip (arrow) during the procedure

The veterinary US operator should have access to high-quality US equipment and have a thorough clinical and radiological knowledge on urinary tract diseases in dogs. In addition to this he/she should be familiar with the US appearance of the most important pathologies to identify them without delay. In this way, the examination can be performed in the shortest possible time and, particularly in less complex cases, yielding a prompt and accurate diagnosis.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Karpenstein H, Klumpp S, Seyrek-Intas D, Kramer M. Ultrasonography of urinary tract diseases in the dog and cat. Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 2011;39(4):281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborne CA, Lulich JP, Kruger JM, Ulrich LK, Koehler LA. Analysis of 451,891 canine uroliths, feline uroliths, and feline urethral plugs from 1981 to 2007: perspectives from the Minnesota Urolith Center. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2009;39(1):183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heng HG, Rohleder JJ, Pressler BM. Comparative sonographic appearance of nephroliths and associated acoustic shadowing artifacts in conventional vs. spatial compound imaging. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2012;53(2):217–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2011.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lulich JP, Osborne CA. Changing paradigms in the diagnosis of urolithiasis. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2009;39(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lulich JP, Adams LG, Grant D, Albasan’ H, Osborne CA. Changing paradigms in the treatment of uroliths by lithotripsy. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2009;39(1):143–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston SD, Kamolpatana K, Root-Kustritz MV, Johnston GR. Prostatic disorders in the dog. Anim Reprod Sci. 2000;60–61:405–415. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith J. Canine prostatic disease: a review of anatomy, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Theriogenology. 2008;70(3):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster RA. Common lesions in the male reproductive tract of cats and dogs. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2012;42(3):527–545. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi J, Jang J, Choi H, Kim H, Yoon J. Ultrasonographic features of pyonephrosis in dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2010;51(5):548–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hylands R. Veterinary diagnostic imaging. Retroperitoneal abscess and regional cellulitis secondary to a pyelonephritis within the left kidney. Can Vet J. 2006;47(10):1033–1035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szatmári V, Osi Z, Manczur F. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage for treatment of pyonephrosis in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218(11):1796–1799. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]