Abstract

Background. Sulfhydryl groups (SH) are considered a key factor in redox sensitive reaction of plasma, and their modification could be considered an expression of abnormal generation of oxygen free radicals. Methods. Fifty consecutive patients with acute brain stroke were enclosed in this study. The plasma concentrations of SH groups were correlated to cytokines (IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), plasma chitotriosidase (Chit), metalloprotease (MMP2–9), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). Results. The results demonstrated a significant reduction of SH groups within 24 hours from the onset of an acute ischemic stroke, a reduction of plasma IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-8, and an increase of Chit and TNF-α in relation to the stroke severity. Conclusion. The observation of an intense microenvironment activation that follows the stroke and the correlation between SH levels and markers of immune response suggest that, especially in stroke, is necessary to maintain the redox function to prevent the brain damage. The reduced SH levels represent an attempt to neutralize the abnormal generation of free radicals. Since the reperfusion of brain after ischemic event represents a severe oxidative stress, which must be corrected by regeneration of redox sensitive function, pharmacological intervention could be beneficial in this setting.

1. Introduction

Thiols contain functional SH groups within conserved cysteinyl residue, and thiol-containing proteins are now recognised as key players in redox sensitive reactions of plasma [1]. Their redox sensing abilities are thought to occur by electron flow through the sulfhydryl side chain. The majority of thiols present in cellular proteins are within a highly reducing environment and therefore protected, or buffered, against oxidation [2, 3]. Only protein as albumin with accessible thiol groups and high oxidation potentials are likely to be involved in redox mechanisms [4].

Several evidences demonstrate that such thiol-containing proteins are sensitive to thiol modification when exposed to changes in redox state of different tissues [5].

Plasma is the principal source of reduced thiols: their concentration is about 500 umol/L, they have a high molecular mass, and they are chiefly attributable to albumin [6]. In fact, antioxidant functions of albumin are linked to its ability to bind transition metal ions and bilirubin, and to the radical scavenging properties of its thiol groups [7]. Albumin's redox active thiol groups are predominantly in the reduced state. In fact, albumin thiol groups can play an important role in extracellular redox balance and subsequent signalling pathways [8]. In the brain, the redox reaction is maintained by ascorbic acid, which is introduced by meals, and it is maintained in the redox status inside the brain, where it protects the cerebral structures from the oxidation [9].

Stroke is a frequent neurological accident in old age and its prevalence in Western countries is high [10]. After an acute brain event, the early glial and endothelial cells are induced to produce transcription of tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin IL-6, which is followed by a cascade of modulator inflammatory pathways [11]. Local endothelia is transformed into a prothrombotic state allowing peripheral mono- and polymorphonuclear cytotoxic cells to be chemoattracted into the lesion site [12, 13]. With a few exceptions [14], a relationship between the extent of the brain damage and the early increase of TNF-α and IL-6 plasma levels has generally been reported in stroke [12–14]. Though the topic remains controversial, this process induces an abnormal generation of oxygen free radicals by microenvironment cells. Moreover, infiltrated macrophages contribute further to brain damage through the synthesis of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-10 [15]. Relationships between the extent of brain damage and the plasma level of TNF-α, IL-6, and, recently, chitotriosidase (Chit), a marker of macrophage activation, are reported, though usually in strict relation to pre-existing and concomitant infectious inflammatory diseases [16]. Our group demonstrated that this response is generated also in absence of infection or other mechanism of macrophage activation [17], limiting this phenomenon to the ischemic event. In these studies, plasma chitotriosidase and TNF-α correlated to the extent of stroke severity and to CT lesion volume, and the levels of these two markers to date could be considered the more sensible parameters to follow the stroke event.

The aim of this study is to evaluate and try to correlate the plasma concentrations of SH groups to brain damage volume, to serum cytokines (IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), plasma chitotriosidase (Chit), metalloprotease (MMP2–9), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and to thioles (cysteine, cysteinylglycine, homocysteine, and glutathione), in 50 consecutive patients with acute brain ischemia without concomitant symptoms or signs of inflammatory infectious diseases. The evaluation of these possible mediators of stroke could permit to better characterize the redox reaction in the pathogenesis of stroke damage.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

Fifty consecutive Caucasian patients with an acute ischemic stroke, 30 males and 20 females, mean age 64 (range 40–82), were enrolled for this study at Institute of Neurology, University of Sassari, Italy. Blood samples were drawn within 24 hours after stroke onset and before pharmacologic intervention. Samples were centrifuged and stored at −80°C until assayed. Exclusion criteria were the clinical evidence of infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases, malignancy, severe cardiac or renal or hepatic diseases, recent transient ischemic attack or previous ischemic-hemorrhagic strokes, atheromatous diseases, arteriosclerotic heart disease, hypertension, and pulmonary diseases, anticoagulant or acetylsalicylic acid therapies. An informed consent to the study was obtained from all patients or their relatives, and the protocol of study was approved by Ethical Committee of Sassari University.

All patients underwent repeated neurological examinations, electrocardiography and ultrasound tomography of carotid and vertebral arteries. Stroke severity was evaluated and scored by administering the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on admission (0–42). NIHSS provides optimal discrimination of 30-day mortality risk, more than 75% for patients with a score of at least 40. The NIHSS is a tool used by healthcare providers to objectively quantify the impairment caused by a stroke. The NIHSS is composed of 11 items, each of which scores a specific ability between 0 and 4. For each item, a score of 0 typically indicates normal function in that specific ability, while a higher score is indicative of some level of impairment. The individual scores from each item are summed in order to calculate a patient's total NIHSS score. The maximum possible score is 42, with the minimum score being a 0 (Table 1).

Table 1.

National institutes of health stroke scale.

| Score | Stroke severity |

|---|---|

| 0 | No stroke symptoms |

| 1–4 | Minor stroke |

| 5–15 | Moderate stroke |

| 16–20 | Moderate to severe stroke |

| 21–42 | Severe stroke |

Brain CT was routinely performed on patient admission and at 7 days by means of a spiral-CT HISPEED/LX/I (General Electric, USA). Each scan was 120 KV, 160 mA, 5 mm thickness, and 2 sec acquisition time. To avoid imprecise estimations of the lesion volume, due to the different three-dimensional conformation of the lesion, we used an accurate technique for calculating the volume of ischemic brain lesion according with the Cavalieri's principle, as described [14]. A control group represented by 20 healthy subjects, mean age 55 (range 35–70), not suffering of cardiovascular disease, atheromatous diseases, arteriosclerotic heart disease, hypertension, pulmonary diseases, and carotid atherosclerosis, was included in this study.

2.2. Cytokines

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests for human IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-8 and human TNF-α (Euroclone, Switzerland) were performed at the Institute of Neurology, University of Sassari, Italy, according to indications and suggestions of the manufacturer. VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule), ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1), and BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Values were expressed as pg/mL while VCAM-1 was expressed as ng/mL. The intra-assay imprecision was <5%, whereas the interassay imprecision was <8%. MMP2–9 was measured by the zymogram method. The gelatinolytic activity is given in arbitrary units (units/ug protein).

2.3. Thioles

Plasma thioles (cysteine, cysteinylglycine, homocysteine, glutathione) were measured in HPLC and expressed in μmol/L at the Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory of Catholic University, Rome, Italy. Inter-assay coefficient of variation was 3.6%, calculated by measuring 15 replicates of a serum sample in the same day. Plasma homocysteine > 15 μmol/L was considered elevated.

2.4. Chit Activity

Chit activity was measured in plasma according to the method reported in Sotgiu et al. [17], at Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania, Italy. Chit activity was measured as nanomoles of substrate (4-methylumbelliferyl-beta-D-N,N′,N′′triacetylchitotriose, Sigma Chemical Co., USA). Briefly, Chit activity was measured incubating 5 μL of undiluted plasma with 100 μL of a solution containing 22 mMol/L of the fluorogenic substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl-beta-D-N,N,N-triacetylchitotriose (Sigma Chemical Co.) in 0.5 M citrate phosphate buffer pH 5.2, for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by using 2 mL of 0.5 mol/L Na2CO3/NaHCO3 buffer, pH 10.7. The fluorescence of formed 4-methylumbelliferone was read on a Hitachi 2500 fluorometer, at 365 nm excitation and 450 nm emission. Chit activity was expressed as nanomoles of substrate hydrolyzed per milliliter per hour (nmol/mL per h). Patients with plasma Chit activity below 2.5 nmol/mL per h were considered as Chit deficient.

2.5. Dosage of SH

SH groups were evaluated according to Ellman reaction [18] at the Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory of Catholic University, Rome, Italy, performing the spectrophotometer measurements on an automated chemistry analyser (OLYMPUS 400). The assay is based on the reaction of the SH groups with 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB, 2.5 mM) in Tris-HCl 0.25 M and EDTA 20 mM (pH 8.2) that develops a yellow-coloured compound, which absorbs at 405 nm. The calibration was obtained by using GSH 1000 μM solution as standard. Intra-assay imprecision was <5%, calculated by measuring the same sample in ten different days. The method is linear up to 10 mM/L, and the sensitivity is 10 mM/L. A control group was selected among healthy individuals who underwent for health balance and resulted in good conditions at the clinical examination.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Clinical data and inflammatory biomarkers were expressed as median and range and/or mean ± SD where possible. Differences between groups were evaluated through the Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test. Correlations between inflammatory markers and clinical variables were assessed by using the Spearman Rank Order Correlation coefficient (r), and the P value was considered significant when <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Outcome

The median NIHSS score was 30 (range 0–42). The intrinsic property of the NIHSS scale (Table 1) allowed us stratifying patients in two groups, with better (NIHSS score ≤ 30; 30 patients) and worse outcome (NIHSS score of at least >30; 20 patients). The clinical parameters in the two groups are reported in Table 2. A significant difference was found for VCAM and BDNF, ICAM, and MMP2–9 between the two groups. The VCAM, BDNF, and ICAM values were higher than in healthy controls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory parameters of 50 patients with brain stroke divided in function of NIHSS score ≤30 and >30.

| Age (yrs) | VCAM | BDNF | ICAM | MMP2–9 | |

|

| |||||

| (A) NIHSS ≤ 30 n. 30 (M. 20, F. 10) |

67.3 ± 13.0 | 519 ± 205 | 43.23 (13.94–337.4) | 248.6 ± 86.6 | 124.2 ± 64.1 |

| (B) NIHSS > 30 n. 20 (M. 11, F. 9) |

70.3 ± 7.98 | 683.2 ± 404.0 | 121.8 (20–1303.9) | 360.35 ± 179.71 | 239.6 ± 152.5 |

| A versus B | P = 0.36 | P = 0.064 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.005 | P = 0.0006 |

| Control groups | 55 (35–70) | 15.96 ± 4.024 | 14.24 ± 6.88 | 201.2 ± 55.0 | — |

VCAM: Cytokine-induced cell adhesion molecule (ng/mL); BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (pg/mL); ICAM: intercellular adhesion molecules (pg/mL); MMP2–9: matrix metalloprotease 2–9 (units/ug protein).

3.2. Cytokines, Chitotriosidase, SH Groups, and Thioles

The SH concentration was significantly lower (104.5 ± 67.6 mmol/L) in stroke patients compared to healthy controls (578.6 ± 63.6 mmol/L) (P = 0.0001) and significantly lower in the subgroup with worse outcome (P = 0.030) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Cytokines (pg/mL), TNF-α, TC volume, Chit (nmol/mL/h) and SH groups (mmol/L) in 50 patients with brain stroke divided in function of NIHSS score ≤30 and >30.

| Parameters | IL-1b | IL-6 | IL-8 | TNF-α | TC mm3 | Chit | SH groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) NIHSS ≤ 30 n. 30 (M. 20, F. 10) |

212.42 (4.1–1096) | 12.23 ± 4.53 | 74.64 ± 16.47 | 52.74 ± 26.86 | 617 (355–5998) | 21.90 ± 15.62 | 121.94 ± 72.95 |

| (B) NIHSS > 30 n. 20 (M. 11, F. 9) |

166.5 (0.2–975.08) | 9.55 ± 5.71 | 60.32 ± 16.36 | 225.32 ± 163.60 | 6611 (185–20836) | 50.35 ± 35.36 | 80.63 ± 47.88 |

| A versus B | P = 0.99 | P = 0.071 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0003 | P = 0.030 |

| Control groups | 0–2.4 | 0.0–5.6 | 1.9–17.4 | 0.0–13.3 | — | 0.0–25 | 578.6 ± 63.6 |

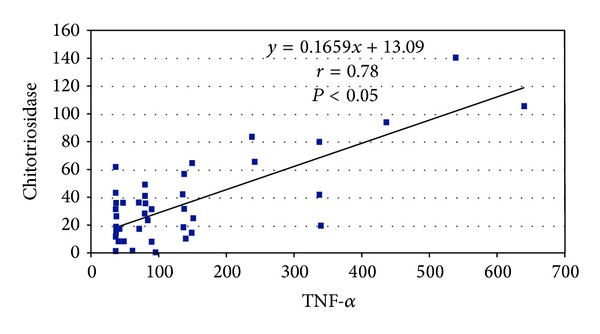

Cytokines as IL-6 and IL-8 were higher in patients with NIHSS score <30 (P = 0.071 and P = 0.004, resp.), but the IL-1b was not significantly higher in the same patients. TNF-α and chitotriosidase were higher in patients with NIHSS score >30 (P = 0.0001 and P = 0.0003 resp.) compared to that with NIHSS score <30 (see Table 3). The median lesion volume was 987 mm3, significantly larger (P < 0.05) in patients with worse outcome (median 6611 mm3; range 185–20836) as compared to those with better outcome (median 617, range 355–5998). A significant correlation was found between TNF-α and Chit (P < 0.05) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between TNF-α and chitotriosidase in 50 patients with brain stroke.

The thioles were all in the normal range for age, and the slight differences between the two groups NIHSS ≤30 or >30 were not significant except glutathione that was lower in all patients (see Table 4). The correlation between homocysteine and SH was not significant (P = 0.84). A direct positive correlation was found between lesion volume and NIHSS score (r = 0.59, P = 0.01) and negative with SH groups (r = −0.60, P = 0.0001). Significant correlation was found between SH and all the other considered parameters with exception of TNF-α and ICAM (see Table 5).

Table 4.

Thioles (μmol/L) in 50 patients with brain stroke divided in function of NIHSS score ≤30 and >30.

| Parameters | Cysteine | Cysteinylglycine | Homocysteine | Glutathione |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) NIHSS ≤ 30 n. 30 (M. 20, F. 10) |

196.58 ± 97.65 | 28.16 ± 19.20 | 7.93 ± 3.84 | 1.81 ± 1.81 |

| (B) NIHSS > 30 n. 20 (M. 11, F. 9) |

206.72 ± 104.7 | 26.30 ± 16.79 | 9.22 ± 7.86 | 1.35 ± 1.18 |

| A versus B | P = 0.72 | P = 0.72 | P = 0.44 | P = 0.32 |

| Controls groups | 193 ± 39.8 | 24.6 ± 6.2 | 9.3 ± 3.7 | 3.05 ± 2.0 |

Table 5.

Spearman rank order correlation of 50 patients with brain stroke.

| All patients | Age | mm3 | NIHSS | SH | IL-1b | IL-6 | IL-8 | TNF-α | Chit | MMP2–9 | ICAM | VCAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | no | no | 0.219 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| P | 0.0125 | |||||||||||

| mm3 |

||||||||||||

| r | 0 | 0.59 | −0.60 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| P | 0.01 | 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| NIHSS | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | No | No | −0.415 | −0.351 | 0.816 | 0.435 | 0.488 | 0.497 | 0.363 | ||

| P | 0.0029 | 0.0126 | 0.000 | 0.0017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.0098 | |||||

| SH | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | No | 0.374 | 0.331 | No | −0.296 | −0.469 | No | 0.002 | |||

| P | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.0371 | 0.002 | 0.52 | |||||||

| IL-1b | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | 0.337 | No | No | No | No | No | No | ||||

| P | 0.0171 | |||||||||||

| IL-6 | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | No | −0.296 | −0333 | −0.395 | −0.507 | No | |||||

| P | 0.0371 | 0.0182 | 0.0047 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| IL-8 | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | −0.355 | No | −0.306 | No | No | ||||||

| P | 0.0117 | 0.0310 | ||||||||||

| TNF-α | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | 0.479 | 0.371 | 0.470 | No | |||||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.0082 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Chit | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | No | 0.535 | No | ||||||||

| P | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| MMP2–9 | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | 0.372 | No | |||||||||

| P | 0.0080 | |||||||||||

| ICAM | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | 0.317 | ||||||||||

| P | 0.0253 | |||||||||||

| VCAM | ||||||||||||

| r | 0 | |||||||||||

| P |

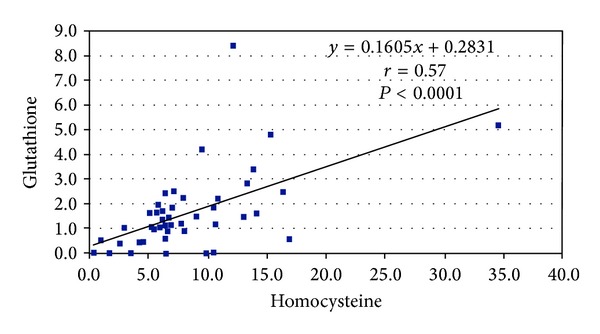

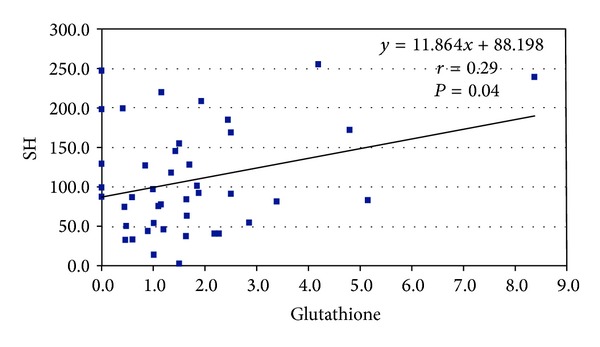

Significant correlations were found between homocysteine and glutathione (P < 0.0001) and between SH and glutathione (P = 0.04) (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Correlation between homocysteine and glutathione in 50 patients with brain stroke.

Figure 3.

Correlation between SH and glutathione in 50 patients with brain stroke.

4. Discussion

There is a strict relation among the extension of tissue injury in cerebral ischemia and generation of oxygen free radicals [19], alteration of vascular reactivity with migration of peripheral leukocyte, and increase in cytokine release [12–14, 20–22]. In our study, we found a significant reduction of SH groups within 24 hours from the onset of an acute ischemic stroke, an increase of plasma TNF-α and Chit, and a reduction of IL-6 and IL-8 in relation to the stroke severity. Moreover, IL-6 and IL-8 directly correlate with SH groups consumption, while Chit and SH correlate negatively, especially in patients with worse outcome (see Table 5). Several studies have demonstrated that the level of IL-6 directly relates to both fever and severity of stroke [16–19, 23], which in turn is directly related to the strength of the acute phase. This demonstrates that the innate reaction of stroke is probably due exclusively to the macrophage activation, secondary to the ischemic event.

In this study, plasma Chit and TNF-α correlated to the extent of the stroke severity, and CT lesion volume and the level of these two marker to date could be considered the more sensible parameters in the followup of the stroke event, as well as IL-6 is considered a marker of the acute event [24].

There are several links between macrophage activation and stroke and infiltrated macrophages, which may contribute to brain damage through a group of potentially neurotoxic factors such as proinflammatory cytokines, free radicals, glutamate, and metalloproteases [25]. The modification of SH groups in the poststroke period may be considered the consequence of free radical generation. The reduced SH levels may represent a tentative to neutralize the abnormal generation of free radicals.

However, on this topic many questions remain to be answered. For example, why chemoattracted or perhaps resident macrophages such as microglia do activate their gene to produce Chit and other cytokines, showing a direct influence on the tissue damage or they simply reflect an epiphenomenon of a pre-existing situation? We cannot argue for any such hypotheses yet. Our results indicate that Chit activity possibly represents the hallmark of an innate macrophage response, and this activation correlates with the severity of stroke [17]. This parameter could be a novel marker of stroke in addition with other cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) [14], even if the cytokine upregulation follows as a fall mechanism not sufficiently regulated, which worse often the clinical course of neurological event.

Another point to consider should be the observation that the patients with stroke could be smokers, alcohol users, or affected by pathologies that reduce the redox status [26, 27] and determine an increase of homocysteinemia. One of the potential injurious effects of hyperhomocysteinemia in the stroke is the free radical generation [28].

In our study, the homocysteine level was found normal, thus indicating that the redox status precedent the acute stroke [29] was normal. The observation of a microenvironment activation, which follows the stroke and the correlation between SH levels and markers of immune response confirms other similar studies [20, 21], but suggests that in stroke is necessary to maintain the redox function to prevent and in particular to contain the brain damage determined by the ischemic event.

Since oxidative stress plays an important role in acute ischemic stroke pathogenesis, free radical formation, and subsequent oxidative damage may be a determinant factor in stroke severity. In fact serum levels of nitric oxide (NO), malondialdehyde (MDA), and glutathione (GSH) were measured within the first 48 h of stroke [30] and correlated with the clinical outcomes. These results suggest deleterious effects of oxidative stress on clinical outcome in acute ischemic stroke and the variation of GSH levels may be an adaptive mechanism during this period.

Since the reperfusion of brain after ischemic event represents a severe oxidative stress that must be corrected by regeneration of redox function [31], a pharmacological intervention could be beneficial in this setting.

Conflict of Interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests in the research.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mr. Giuseppe Rapicavoli, Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania for, his skillful technical assistance in laboratory work.

References

- 1.Chung K-Y, Lee S-J, Chung S-M, Lee M-Y, Bae O-N, Chung J-H. Generation of free radical by interaction of iron with thiols in human plasma and its possible significance. Thrombosis Research. 2005;116(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coan C, Ji J-Y, Hideg K, Mehlhorn RJ. Protein sulfhydryls are protected from irreversible oxidation by conversion to mixed disulfides. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1992;295(2):369–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90530-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soriani M, Pietraforte D, Minetti M. Antioxidant potential of anaerobic human plasma: role of serum albumin and thiols as scavengers of carbon radicals. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1994;312(1):180–188. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran LK, Gutteridge JMC, Quinlan GJ. Thiols in cellular redox signalling and control. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;8(7):763–772. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buczek O, Green BR, Bulaj G. Albumin is a redox-active crowding agent that promotes oxidative folding of cysteine-rich peptides. Biopolymers. 2007;88(1):8–19. doi: 10.1002/bip.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Simplicio P, Frosali S, Priora R, et al. Biochemical and biological aspects of protein thiolation in cells and plasma. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2005;7(7-8):951–963. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camerini S, Polci ML, Bachi A. Proteomics approaches to study the redox state of cysteine containing proteins. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanita. 2005;41(4):451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters T. Biochemistry: Genetics and Medical Afflictions. New York, NY, USA: Academic press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice ME. Ascorbate regulation and its neuroprotective role in the brain. Trends in Neurosciences. 2000;23(5):209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clara JG, De Macedo ME, Pego M. Prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension in the population over 55 years old. Results from a national study. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia. 2007;26(1):11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dziedzic T, Bartus S, Klimkowicz A, Motyl M, Slowik A, Szczudlik A. Intracerebral hemorrhage triggers interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 release in blood. Stroke. 2002;33(9):2334–2335. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000027211.73567.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothwell NJ, Loddick SA, Stroemer P. Interleukins and cerebral ischaemia. International review of neurobiology. 1997;40:281–298. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60724-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castillo J, Rodríguez I. Biochemical changes and inflammatory response as markers for brain ischaemia: molecular markers of diagnostic utility and prognosis in human clinical practice. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2004;17(1):7–18. doi: 10.1159/000074791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sotgiu S, Zanda B, Marchetti B, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers in blood of patients with acute brain ischemia. European Journal of Neurology. 2006;13(5):505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvo C-F, Amigou E, Desaymard C, Glowinski J. A pro- and an anti-inflammatory cytokine are synthetised in distinct brain macrophage cells during innate activation. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2005;170(1-2):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palasik W, Fiszer U, Lechowicz W, Czartoryska B, Krzesiewicz M, Lugowska A. Assessment of relations between clinical outcome of ischemic stroke and activity of inflammatory processes in the acute phase based on examination of selected parameters. European Neurology. 2005;53(4):188–193. doi: 10.1159/000086355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotgiu S, Barone R, Zanda B, et al. Chitotriosidase in patients with acute ischemic stroke. European Neurology. 2005;54(3):149–153. doi: 10.1159/000089935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellman G, Lysko H. A precise method for the determination of whole blood and plasma sulfhydryl groups. Analytical Biochemistry. 1979;93(1):98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leinonen JS, Ahonen J-P, Lönnrot K, et al. Low plasma antioxidant activity is associated with high lesion volume and neurological impairment in stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(1):33–39. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasarica D, Gheorghiu M, Topârceanu F, Bleotu C, Ichim L, Trandafir T. Neurotrophin-3, TNF-alpha and IL-6 relations in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of ischemic stroke patients. Roumanian archives of microbiology and immunology. 2005;64(1–4):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith CJ, Emsley HC, Gavin CM, et al. Peak plasma interleukin-6 and other peripheral markers of inflammation in the first week of ischaemic stroke correlate with brain infarct volume, stroke severity and long-term outcome. BMC Neurology. 2004;4(article 2) doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fassbender K, Rossol S, Kammer T, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines in serum of patients with acute cerebral ischemia: kinetics of secretion and relation to the extent of brain damage and outcome of disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1994;122(2):135–139. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emsley HCA, Smith CJ, Gavin CM, et al. An early and sustained peripheral inflammatory response in acute ischaemic stroke: relationships with infection and atherosclerosis. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2003;139(1-2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waje-Andreassen U, Kråkenes J, Ulvestad E, et al. IL-6: an early marker for outcome in acute ischemic stroke. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2005;111(6):360–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendriks JJA, Teunissen CE, De Vries HE, Dijkstra CD. Macrophages and neurodegeneration. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;48(2):185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durak I, Elgün S, Kemal Bingöl N, et al. Effects of cigarette smoking with different tar content on erythrocyte oxidant/antioxidant status. Addiction Biology. 2002;7(2):255–258. doi: 10.1080/135562102200120505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandhir R, Subramanian S, Koul A. Long-term smoking and ethanol exposure accentuates oxidative stress in hearts of mice. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2003;3(2):135–140. doi: 10.1385/ct:3:2:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Kossi MMH, Zakhary MM. Oxidative stress in the context of acute cerebrovascular stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(8):1889–1892. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson A, Hultberg B, Lindgren A. Redox status of plasma homocysteine and other plasma thiols in stroke patients. Atherosclerosis. 2000;151(2):535–539. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozkul A, Akyol A, Yenisey C, Arpaci E, Kiylioglu N, Tataroglu C. Oxidative stress in acute ischemic stroke. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;14(11):1062–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murín R, Drgová A, Kaplán P, Dobrota D, Lehotský J. Ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress causes structural changes of brain membrane proteins and lipids. General Physiology and Biophysics. 2001;20(4):431–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]