Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether stress or depressive symptoms mediated associations between perceived discrimination and multiple modifiable behavioral risk factors for cancer among 1363 African American adults.

Methods

Nonparametric bootstrapping procedures, adjusted for sociodemographics, were used to assess mediation.

Results

Stress and depressive symptoms each mediated associations between discrimination and current smoking, and discrimination and the total number of behavioral risk factors for cancer. Depressive symptoms also mediated the association between discrimination and overweight/obesity (p values < .05).

Conclusions

Discrimination may influence certain behavioral risk factors for cancer through heightened levels of stress and depressive symptoms. Interventions to reduce cancer risk may need to address experiences of discrimination, as well as the stress and depression they engender.

Keywords: discrimination, stress, depression, cancer risk factors

Stressful experiences with discrimination, defined as unfair treatment due to a person’s racial/ethnic characteristics, are unfortunately quite common among African Americans in the United States1–3 and have been associated with poorer physical and psychological health.4–8 Researchers have recently suggested that experiences of discrimination may at least partially contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health,7,9,10 including disparities in cancer incidence and survival that disproportionately affect African Americans [eg,11,12]. Modifiable behavioral-based risk factors, such as overweight/obesity, inadequate fruit and vegetable intake, smoking, insufficient physical activity, and at-risk alcohol use have each been associated with increased cancer risk among diverse samples [eg,13,14]. Therefore, one mechanism by which discriminatory events may affect cancer risk among African Americans is through associations with increased engagement in these modifiable risk factors. However, the relationships between discrimination and cancer risk behaviors, as well as the mechanisms underlying these potential associations, are unclear.

Findings regarding the associations between discrimination and behavioral risk factors for cancer in African Americans have been mixed. Perceived discrimination has been linked to higher rates of smoking,15–22 problematic alcohol use,16,23–26 and unhealthy eating habits,23 but it has not been linked to insufficient/low physical activity rates16,23,27 or weight status.28,29 However, some research suggests that discrimination is associated with higher levels of physical activity, at least among some subgroups of African Americans [eg, young women 23]. Given that insufficient/low physical activity and overweight/obesity are some of the most common modifiable risk factors among African Americans [cf.30,31], research aimed toward understanding whether discrimination affects these behaviors in African Americans and how it operates is critical. The effects of discrimination on these and other behavioral risk factors for cancer among African Americans might be best understood through a more comprehensive biopsychosocial model that includes the potential for indirect effects via psychological factors, such as stress and depressive symptoms. The generation of new information on the mechanisms underlying relations between discrimination and health among African Americans, including the modifiable behavioral factors that influence health, is needed to better understand and address health inequities involving this population.32

Biopsychosocial theory and the stress and coping framework suggest that discriminatory events are experienced as psychological stressors that can trigger unhealthy behaviors, presumably in efforts to alleviate distress.33 Empirical research has linked perceived discrimination to elevated stress and depressive symptoms32,33 as well as serious/severe psychological distress.2,34 In turn, such psychological symptoms have been linked with a number of behavioral risk factors for cancer, including an unhealthy diet,35–38 increased alcohol consumption,38 insufficient/low physical activity rates,35,36,39 being a smoker,35,36,40,41 and being overweight or obese.42,43 Consequently, stress and depressive symptoms may be the primary mechanisms through which discrimination affects modifiable cancer risk factors among African Americans. However, very few studies have formally examined this possibility by testing indirect effects in mediation analyses. We are aware of only 2 such studies, both of which focused on smoking. One study, conducted among young African American females, indicated that stress mediated the relationship between discrimination and current cigarette smoking.19 Another more recent study using a large population-based sample supported a similar pattern of results among adults.15 These initial results suggest the biopsychosocial model and the stress and coping framework may critically alter our understanding of how perceived discrimination affects engagement in other modifiable risk factors for cancer among African Americans. Research that elucidates biopsychosocial pathways linking discrimination with key health-related outcomes will be informative for the development of interventions to prevent the negative health consequences of discrimination.

The current study examined associations among perceived discrimination, stress and depressive symptoms, and multiple behavioral-based cancer risk factors (ie, overweight/obesity, inadequate fruit and vegetable intake, smoking, low physical activity, at-risk alcohol use, and the total number of risk factors) in a large sample of African American adults living in Houston, Texas. We hypothesized that stress and depressive symptoms would significantly mediate associations between perceived discrimination and behavioral risk factors for cancer.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected through a cohort study investigating associations among biopsychosocial factors and health behaviors in African American adults. Participants were recruited from a large church in Houston, Texas, through printed and televised media within the church and in-person solicitation (eg, during church services, at a church health fair). Individuals were eligible to participate if they were 18 years of age or older, resided in the Houston area, had a functional telephone number, and attended church (although church membership was not a requirement).

In total, 1501 African American adults enrolled in the study from December 2008 to July 2009. Procedures included the completion of surveys at the church where participants viewed questionnaire items on a computer screen and responded using the computer keyboard. Compensation for time and effort included a $30 Visa Debit Card following survey completion. Only participants with complete data on the measures described below (N = 1363) were included in the current study.

Measures

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, partner status, total annual household income, educational level, and employment status. Sociodemographics were included as covariates in the analyses due to known associations with cancer risk behaviors.

Perceived discrimination

The Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale was selected as the measure of perceived discrimination. This measure is a widely used, validated protocol with good psychometric properties.44 The scale includes ten examples of discrimination experienced in different settings (eg, at work, getting medical care, getting services in a store or restaurant). Respondents were asked how often they experienced such forms of discrimination in their day-to-day lives based on their race/ethnicity or skin color, where the response categories were 1=“4 or more times,” 2=“2 or 3 times,” 3=“once,” or 4=“never.” Responses were reverse scored and summed so higher scores were indicative of greater perceived discrimination. The Cronbach’s alpha for the Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale in this sample was 0.91.

Perceived stress

The Perceived Stress Scale-4 (PSS-4)45 is a 4-item self-report scale that asks respondents to indicate how often they experience certain situations, such as “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” and “In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?” (reverse scored). Responses were summed with a potential range of zero to 16, where higher scores indicate greater perceived stress. The Cronbach’s alpha for the PSS-4 in this sample was 0.73.

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression 10-item scale (CESD-10) was used to assess the degree of depressive symptoms experienced over the past week.46,47 Items include “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me” and “I felt hopeful about the future” (reversed scored). Responses were summed with a potential range of zero to 30, where higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha for the CESD-10 in this sample was 0.82.

Overweight/Obesity status

Overweight/ obesity status was determined based on staff-administered height and weight measurements, which were converted to body mass index (BMI; kg/m2). Participants with a BMI ≥ 25 were considered overweight/obese.

Fruit and vegetable intake

Fruit and vegetable intake was assessed with the NCI 5-A-Day fruit and vegetable questionnaire.48 This questionnaire yielded a continuous variable of daily fruit and vegetable servings that was highly skewed. Because of this, we chose to focus on a binary outcome whereby participants were classified as meeting recommendations for daily intake (≥5 servings of fruits and vegetables a day) or not meeting recommendations for daily intake (<5 servings of fruits and vegetables a day).

Smoking status

Smoking status was assessed with survey items resulting in classification as a current smoker (smoked ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime and currently smoke) or former smoker/never smoker (ie, smoked ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime but quit or smoked <100 cigarettes in lifetime).

Insufficient physical activity

Physical activity was assessed with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire - Short Format (IPAQ). The IPAQ is a self-report questionnaire used to measure the amount of time spent in moderate activity, vigorous activity, and walking during the past 7 days.49 Time spent engaging in each type of activity was multiplied by the corresponding metabolic equivalent (MET) value, which is a metric used to quantify energy expenditure [ie, the ratio of energy expended during an activity to the energy expended during rest].50 MET minutes were summed to arrive at the total weekly MET minutes spent in physical activity. Because resulting data were highly skewed, participants were classified as engaging in low or moderate/high rates of physical activity during the previous week based on total weekly MET minutes, the number of days per week engaged in physical activity, and the amount of time spent in each type of physical activity (see Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the IPAQ, 2005). The short version of the IPAQ has good test-retest reliability and acceptable criterion validity against the Computer Science Applications, Inc. accelerometer.49 Participants were considered insufficiently active if they were categorized as having low activity during the previous week.

At-risk drinking

At-risk drinking was assessed using the Alcohol Quantity and Frequency Questionnaire, a self-report measure of the average alcohol consumption on each day of the week over the last 30 days. Males were classified as atrisk drinkers if they consumed an average of >14 drinks per week, and females were classified as atrisk drinkers if they consumed an average of >7 drinks per week.51

Total number of risk factors

The total number of behavioral cancer risk factors was determined by summing the number of risk factors for which the specified criteria were met (ie, overweight/obesity, not meeting fruit and vegetable intake recommendations, current smoking, low physical activity, and at-risk drinking). Scores could range from zero to 5 risk factors.

Data Analysis

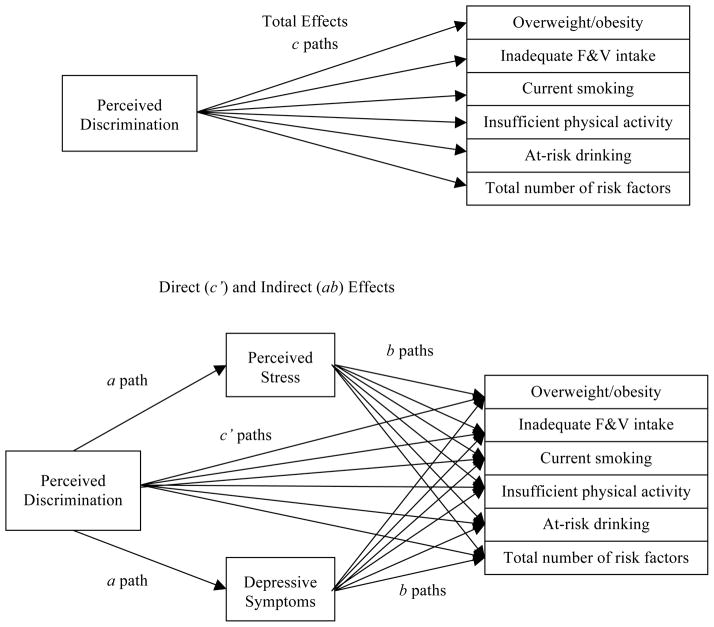

This study was designed to examine the indirect effects of perceived discrimination on behavioral cancer risk factors through stress and depressive symptoms among a subset of participants with complete data from the parent project (Figure 1). First, any potential differences between included and excluded participants on the variables of interest were assessed, as data allowed. Next, a preliminary linear regression analysis was conducted among the included participants to examine relations between each sociodemographic variable and perceived discrimination while controlling for other sociodemographic variables. Finally, main analyses consisted of a series of single mediation models to assess the indirect effects of perceived discrimination on each behavioral cancer risk factor through stress and depressive symptoms. Each model was adjusted for age, sex, partner status, total annual household income, educational level, and employment status. Analyses involving overweight/ obesity status additionally controlled for fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity. These models were run using an INDIRECT macro52 in SPSS 19.0, which also provided information regarding the total effects of perceived discrimination on each behavioral cancer risk factor (ie, the direct associations between these variables). Indirect effects were specifically tested using a non-parametric, bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure. 53 The bootstrapping procedure generated an empirical approximation of the sampling distribution of the product of the estimated coefficients in the indirect paths using 5000 resamples from the data set. The proportion of the effect that was mediated (PME) in each model was calculated by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect (PME = ab/c).54

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Conceptual Model of the Total (c path) and Indirect Effect (ab paths) of Perceived Discrimination on Behavioral Risk Factors for Cancer Through Proposed Mediators

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The current study consisted of the 1363 participants with complete data (ie, no missing data). Participants (25.0% male) were 45.4 years old on average (SD=12.5). Three quarters of participants were employed, 49.4% reported at least a Bachelor’s Degree, and 35.2% reported an annual household income of at least $80,000. See Tables 1 and 2 for participant characteristics and their interrelations with other study variables.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics and Their Interrelations

| Participant Characteristics | Mean (SD) / [Percentage] | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 45.4 (12.5) | 1363 | 1.000 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 2. Sex | .031 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Female | [75.0] | 1022 | |||||||||

| Male (REF) | [25.0] | 341 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 3. Education | .048 | .097** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| < Bachelor’s Degree (REF) | [50.6] | 690 | |||||||||

| Bachelor’s Degree | [30.0] | 409 | |||||||||

| ≥ Master’s Degree | [19.4] | 264 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 4. Annual household income | .055* | −.140** | .344** | 1.000 | |||||||

| < $40,000 (REF) | [25.0] | 341 | |||||||||

| $40,000–79,999 | [39.8] | 542 | |||||||||

| ≥ $80,000 | [35.2] | 480 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 5. Partner status | .179** | −.217** | .046 | .421** | 1.000 | ||||||

| Partner | [43.6] | 594 | |||||||||

| No Partner (REF) | [56.4] | 769 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 6. Employment status | −.097** | −.045 | .198** | .294** | .052 | 1.000 | |||||

| Employed | [75.2] | 1025 | |||||||||

| Unemployed (REF) | [24.8] | 338 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 7. Perceived discrimination | 20.4 (7.3) | 1363 | −.017 | −.085** | −.004 | −.019 | .011 | −.009 | 1.000 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| 8. Stress | 4.6 (3.0) | 1363 | −.177** | .051 | −.141** | −.165** | −.045 | −.044 | .148** | 1.000 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| 9. Depressive symptoms | 5.7 (5.0) | 1363 | −.109** | .067* | −.174** | −.203** | −.102** | −.104** | .178** | .674** | 1.000 |

p <. 01;

p < .05

Note.

Interrelations between participant characteristics were evaluated using Pearson correlations for continuous-continuous variable associations, Point-biserial correlations for continuous-binary associations, Spearman correlations for continuous-ordinal and ordinal-ordinal associations, Phi coefficients for binary-binary associations, and Rank biserial coefficient for ordinal-binary associations. Discrimination = Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale; Stress = Perceived Stress Scale; Depressive symptoms = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression 10-item scale. REF= Reference group.

Table 2.

Relations of Participant Characteristics and Behavioral Risk Factors for Cancer

| Overweight/ obese | Inadequate F&V intake | Current smoking | Insufficient physical activity | At-risk drinker | # of risk factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Participant Characteristics | No (REF)/Yes N = 229/1134 |

No (REF)/Yes N = 1140/223 |

No (REF)/Yes N = 1247/116 |

No (REF)/Yes N = 1004/359 |

No (REF)/Yes N = 1296/67 |

Mean/Std 2.1 (±0.8) |

| 1. Age | .223** | .007** | −.011 | .004 | −.056* | .056* |

|

| ||||||

| 2. Sex | −.042 | .040 | −.139** | .157** | .006 | .001 |

| Female | ||||||

| Male (REF) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 3. Education | −.080* | .002 | −.297** | .054 | −.136* | −.064* |

| < Bachelor’s Degree (REF) | ||||||

| Bachelor’s Degree | ||||||

| ≥ Master’s Degree | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 4. Annual household income | .015 | .001 | −.214** | −.008 | −.023 | −.045 |

| < $40,000 (REF) | ||||||

| $40,000–79,999 | ||||||

| ≥ $80,000 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 5. Partner status | .051 | .015 | −.024 | −.008 | −.029 | −.004 |

| Partner | ||||||

| No Partner (REF) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 6. Employment status | .015 | −.090** | −.068* | .043 | −.034 | .040 |

| Employed | ||||||

| Unemployed (REF) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 7. Perceived discrimination | .029 | .010 | .039 | −.014 | .048 | .028 |

|

| ||||||

| 8. Stress | .013 | −.022 | .086** | .054* | .055* | .092** |

|

| ||||||

| 9. Depressive symptoms | .045 | −.026 | .105** | .054* | .042 | .112** |

p < .01;

p < .05

Note.

Interrelations between participant characteristics and risk factors were assessed using Pearson correlations for continuous-continuous variable associations, Point-biserial correlations for continuous-binary associations, Spearman correlations for continuous-ordinal and ordinal-ordinal associations, Phi coefficients for binary-binary associations, and Rank biserial coefficient for ordinal-binary associations. Discrimination = Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale; Stress = Perceived Stress Scale; Depressive symptoms = Center for Epide-miological Studies Depression 10-item scale. REF= Reference group. Std = standard deviation.

Analyses failed to support any statistically significant differences between the included participants (N = 1363) and the additional participants from the parent project with incomplete data (p values ≥ .44).

Preliminary Analysis

See Table 3 for results of a preliminary analysis assessing differences in perceived discrimination as a function of sociodemographic variables. Controlling for the other sociodemographic variables, results indicated that men reported higher levels of perceived discrimination than women (β=−1.54, t= −3.27, p = .001).

Table 3.

Adjusted Relations of Sociodemographics and Perceived Discrimination

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients β | Std. Error | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.010 | .016 | −.620 | .533 |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | −1.540 | .471 | −3.27 | .001 |

| Male (REF) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| < Bachelor’s Degree (REF) | ||||

| Bachelor’s Degree | −.543 | .473 | −1.15 | .251 |

| ≥ Master’s Degree | 1.042 | .566 | 1.84 | .066 |

|

| ||||

| Annual household oncome | ||||

| < $40,000 (REF) | ||||

| $40,000–79,999 | −.186 | .536 | −.350 | .728 |

| ≥$80,000 | −.368 | .612 | −.600 | .548 |

|

| ||||

| Partner status | ||||

| Partner | −.002 | .449 | −.010 | .996 |

| No Partner (REF) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | −.158 | .481 | −.330 | .742 |

| Unemployed (REF) | ||||

Note.

Results represent relations between each sociodemographic variable and perceived discrimination controlling for the other sociodemographic variables, as assessed using linear regression.

Main Analyses

None of the direct associations between perceived discrimination and behavioral risk factors were significant (p values ≥ .06); however, there were a few significant indirect effects. Specifically, perceived discrimination had an indirect effect on smoking status (CIs.95= .0006, .0096; .0018, .0115) and the total number of risk factors (CIs.95= .0006, .0028; .0012, .0036) through both stress and depressive symptoms. Specifically, greater discrimination was associated with greater stress and depressive symptoms, which were associated with a higher likelihood of current smoking and a greater number of behavioral risk factors for cancer. Additionally, the indirect effect of discrimination on overweight/obesity status through depressive symptoms was significant (CIs.95= .0013, .0108). Specifically, greater discrimination was associated with greater depressive symptoms, which were associated with higher odds of overweight/obesity. Finally, both stress and depressive symptoms were suppressors of the effect of perceived discrimination on insufficient physical activity (CIs.95= .0001, .0060; .0005, .0069). Suppression occurs when the association between perceived discrimination and insufficient physical activity increases (rather than decreases) when the mediator is included in the model.55 This inconsistent mediation (suppressor effect) occurred because the directional relation between discrimination and insufficient physical activity was negative, whereas the directional relations between stress/depressive symptoms and insufficient physical activity were positive in this sample. No indirect effects emerged for fruit and vegetable intake or at-risk drinking. See Table 4 for a summary of the mediation results.

Table 4.

Results of Adjusted Models Examining Relations of Discrimination and Behavioral Risk Factors Through Proposed Mediators

| Mediator = Stress | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Coefficient Estimates | BCa | |||||||

| Behavioral Risk Factor | a path | b path | c path | c’ path | ab | 95% | CI | PME (%) |

| Overweight/obese | 0.063 | 0.0488 | 0.0121 | 0.0089 | 0.0031 | −0.0003 | 0.0069 | - |

| Inadequate F&V intake | 0.063 | −0.0150 | 0.0054 | 0.0064 | −0.0010 | −0.0045 | 0.0023 | - |

| Current smoking | 0.063 | 0.0755 | 0.0113 | 0.0066 | 0.0047 | 0.0006 | 0.0096 | 41.59 |

| Insufficient physical activity | 0.063 | 0.0427 | −0.0002 | −0.0030 | 0.0027 | 0.0001 | 0.0060 | <0 |

| At-risk drinking | 0.063 | 0.0532 | 0.0311 | 0.0278 | 0.0033 | −0.0022 | 0.0092 | - |

| Total number of risk factors | 0.063 | 0.0246 | 0.0034 | 0.0019 | 0.0015 | 0.0006 | 0.0028 | 44.12 |

| Mediator = Depressive symptoms | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Coefficient Estimates | BCa | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Behavioral Risk Factor | a path | b path | c path | c’ path | ab | 95% | CI | PME (%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Overweight/obese | 0.124 | 0.0456 | 0.0121 | 0.0069 | 0.0056 | 0.0013 | 0.0108 | 46.28 |

| Inadequate F&V intake | 0.124 | −0.0170 | 0.0054 | 0.0076 | −0.0020 | −0.0065 | 0.0016 | - |

| Current smoking | 0.124 | 0.0498 | 0.0113 | 0.0043 | 0.0062 | 0.0018 | 0.0115 | 54.87 |

| Insufficient physical activity | 0.124 | 0.0271 | −0.0002 | −0.0040 | 0.0034 | 0.0005 | 0.0069 | <0 |

| At-risk drinking | 0.124 | 0.0193 | 0.0311 | 0.0287 | 0.0024 | −0.0038 | 0.0082 | - |

| Total number of risk factors | 0.124 | 0.0180 | 0.0034 | 0.0012 | 0.0022 | 0.0012 | 0.0036 | 64.71 |

Note.

Results were calculated using the SPSS INDIRECT macro syntax for estimating models with continuous (or binary) outcomes and continuous mediators. Ordinary least squares regression is used for continuous outcomes. The a path is the relation between perceived discrimination and the mediator. The b path is the relation between the mediator and the behavioral risk factor, controlling for perceived discrimination. The c path is the total effect of perceived discrimination on the behavioral risk factor. The c’ path is the relation of perceived discrimination and the behavioral risk factor in the mediated model. ab is the mean of the indirect effect estimates calculated across 5000 bootstrap samples. BCa 95% CI= Bias corrected and accelerated 95% confidence interval. PME = proportion of the mediated effect. Discrimination = Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale; Stress = Perceived Stress Scale; Depressive symptoms = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression 10-item scale. Each model was adjusted for age, sex, partner status, total annual household income, educational level, and employment status. Analyses involving overweight/obesity status additionally controlled for fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity.

DISCUSSION

As suggested by biopsychosocial theory and the stress and coping framework, results of the current study support that perceived discrimination is a psychosocial stressor that may heighten stress and depressive symptoms, which in turn may engender unhealthy behavioral patterns, perhaps in attempt to cope with psychological symptomatology. Specifically, findings suggest that perceived discrimination may indirectly influence smoking via its effects on stress and depressive symptoms, and overweight/obesity status via its effects on depressive symptoms. The results linking perceived discrimination and current smoking via stress complement prior findings citing similar indirect effect among young African Americans females19 and a population-based sample of adults.15 The current study, however, was the first to examine and highlight the indirect role of depressive symptoms in relations between perceived discrimination and smoking and overweight/obesity, respectively. Results also support indirect effects of perceived discrimination on the total number of behavioral risk factors for cancer. Greater perceived discrimination was associated with higher stress and depressive symptoms, which were associated with a greater number of behavioral risk factors for cancer. This result is noteworthy given that, although each modifiable behavior examined in this study is thought to increase cancer risk independently, the combination of multiple risk factors may work synergistically to increase risk for chronic disease and related mortality to a greater degree.56–59 As a result, church-based interventions to reduce cancer risk among African Americans, at least among African Americans from the South, may need to address experiences of discrimination as well as the stress and depression that these may engender.

Despite the presence of indirect effects for some behavioral cancer risk factors, perceived discrimination did not affect all of the risk factors examined via stress or depressive symptoms. In the case of at-risk alcohol use, this may be attributable to the low prevalence of at-risk drinking (4.9%) in the current church-going sample, which is consistent with research suggesting that religious attendance is associated with lower alcohol use in African Americans.60 Thus, null findings in this regard may not be generalizable to more population-based samples of African Americans. Similarly, the current results failed to support indirect associations of discrimination and the failure to meet daily recommendations for fruit and vegetable intake via stress or depressive symptoms. Future studies might explore whether discrimination affects other aspects of dietary consumption via relations with stress and depressive symptoms, such as an increased consumption of foods with high concentrations of fats and sugars (ie, “comfort foods”). A number of studies suggest that stress, and the experience of negative affect more generally, decreases the quality of dietary intake in this regard, particularly among women [cf. 38,61–65]. Finally, results indicated that stress and depression were suppressors of the relation between perceived discrimination and insufficient physical activity, rather than mediators of that relation. These results were driven by the negative directional relation between discrimination and insufficient physical activity countered with the positive directional relation between stress/depressive symptoms and insufficient physical activity. Although this relation was not statistically significant in this sample, at least one previous study has supported significant links between perceived discrimination and higher rates of physical activity, but only among young African American women.23 The literature on the relation between discrimination and physical activity, however, is mixed overall with most studies citing null effects as was the case in this sample.16,23,27 Additional research, perhaps using a more complex model than the one tested in the current study, is needed to better understand how discrimination might affect physical activity and through what mechanisms. The potentially moderating role of sex might also be of interest in this regard.

In the current study, there were no significant direct relations between discrimination and modifiable behavioral risk factors for cancer, including overweight/obesity, inadequate fruit and vegetable intake, smoking, insufficient/low physical activity, or at-risk alcohol use. These results differ from some previous studies that have supported significant associations between discrimination and current smoking,15–22 problematic alcohol use,16,23–26 and less healthy eating.23 However, results are consistent with other studies citing a lack of association between discrimination and insufficient physical activity rates16,23,27 and body mass index. 28,29 Discrepancies between the current findings and those of other studies may reflect differences in sample characteristics or measurement tools. Future studies in this area should seek to include a more diverse population of African American adults.

The present study was cross-sectional in nature, precluding assumptions of temporal associations or causality. In addition, the potential for reverse causality in mediational analyses using crosssectional data cannot be ruled out. Future studies might examine mediational pathways between discrimination and behavioral cancer risk factors using longitudinal data that can elucidate temporal associations. An additional limitation concerns the convenience sample of church-based African American adults from a large metropolitan city in the South. Participants were largely female and generally well-educated, and results may not generalize to other populations. Future research should seek to include larger, population-based samples to examine indirect relations of discrimination and behavioral risk factors through stress and depressive symptoms. Also, the current study exclusively focused on everyday discrimination. Relations of other conceptualizations of discrimination [eg, discrimination associated with major life events66] and behavioral risk factors for cancer were not examined in this study but could be the focus of future research. In addition, the extent to which recall bias affected reports of perceived discrimination is unknown, as is information on the recency or chronicity of discrimination experienced. Finally, the current study examined 2 potential psychosocial mediators of relations between discrimination and risk factors: stress and depressive symptoms. Future research might address other potential mediators of these relations, such as serious/severe psychological distress,2,34 which were not measured in the current study.

Despite limitations, the current study is strengthened by a large sample of African American adults, assessment of multiple behaviors related to cancer risk, statistical control of important sociodemographic covariates, and examination of psychosocial mechanisms underlying associations between discrimination and cancer risk. Results suggest that experiences with everyday discrimination may engender engagement in certain behavioral risk factors for cancer through their associations with greater stress and depressive symptoms. In light of these results, future research should strive to identify protective factors that might improve coping with discrimination and/or prevent discrimination- associated stress from triggering cancer risk behaviors. Although research does not clearly support the use of any one protective strategy in this regard, social support, racial/ethnic identity, and religious coping each show some promise for preventing mental and physical health effects of discrimination.8,67–70 It is our hope that this ongoing area of research will lead to the development and dissemination of interventions that pay close attention to psychological responses to discrimination (ie, stress and depressive symptoms) in order to reduce cancer risk, improve quality of life, and eliminate health disparities for African Americans. The current work adds to the understanding of how discrimination might potentially affect the health of African American adults, but more preventative work is needed on a societal level to combat racism by eliminating the structural and social determinants of current discriminatory practices across the nation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the University Cancer Foundation; the Duncan Family Institute through the Center for Community-Engaged Translational Research; faculty fellowship through the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment (to CEA); the Ms. Regina J. Rogers Gift: Health Disparities Research Program; the Cullen Trust for Health Care Endowed Chair Funds for Health Disparities Research; the Morgan Foundation Funds for Health Disparities Research and Educational Programs; The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center startup funds (to LRR); and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health through a cancer prevention fellowship training grant (R25ECA56452) and The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the project supporters.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no competing interests pertaining to this research.

References

- 1.Ayalon L, Gum AM. The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15:587–594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, et al. Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1704–1713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis SK, Liu Y, Quarells RC, Din-Dzietharn R. Stress-related racial discrimination and hypertension likelihood in a population-based sample of African Americans: the metro atlanta heart disease study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4):585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brondolo E, Brady Ver Halen N, Pencille M, et al. Coping with racism: a selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brondolo E, Gallo LC, Myers HF. Race, racism and health: disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, et al. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):894–911. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor TR, Williams CD, Makambi KH, et al. Racial discrimination and breast cancer incidence in US black women: the black women’s health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(1):46–54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of black-white disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2913–2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacInnis RJ, English DR, Hopper JL, Giles GG. Body size and composition and the risk of gastric and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2005;118(10):2628–2631. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purnell JQ, Peppone LJ, Alcaraz K, et al. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress, and current smok ing status: results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system reactions to race module, 2004–2008. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):844–851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Racial discrimination, racial/ethnic segregation, and health behaviors in the CARDIA study. Ethn Health. 2012 Aug 22; doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.713092. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Jr, Williams DR, et al. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the coronary artery risk development in adults study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Racial discrimination and cigarette smoking among blacks: findings from two studies. Ethn Dis. 2000;10(2):195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, et al. African American girls’ smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nurs Res. 2002;51(3):183–189. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The Schedule of Racist Events: a measure of racial discrimination and a stud of its negative physical and mental health consequences. J Black Psychol. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Robinson EL, et al. Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95(2):238–240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, et al. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brodish AB, Cogburn CD, Fuller-Rowell TE, et al. Perceived racial discrimination as a predictor of health behaviors: the moderating role of gender. Race Soc Probl. 2011;3(3):160–169. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9050-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yen IH, Ragland DR, Greiner BA, Fisher JM. Racial discrimination and alcohol-related behavior in urban transit operators: findings from the San Francisco muni health and safety study. Public Health Rep. 1999;114(5):448–458. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.5.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen IH, Ragland DR, Greiner BA, Fisher JM. Workplace discrimination and alcohol consumption: findings from the san francisco muni health and safety study. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin JK, Tuch SA, Roman PM. Problem drinking patterns among African Americans: the impacts of reports of discrimination, perceptions of prejudice, and “risky” coping strategies. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):408–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shelton RC, Puleo E, Bennett GG, et al. Racial discrimination and physical activity among low-income-housing residents. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelton RC, Puleo E, Bennett GG, et al. The association between racial and gender discrimination and body mass index among residents living in lower-income housing. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(3):251–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunte HE, Williams DR. The association between perceived discrimination and obesity in a population-based multiracial and multiethnic adult sample. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1285–1292. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghafoor A, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):326–341. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkissyan M, Wu Y, Vadgama JV. Obesity is associated with breast cancer in African-American women but not Hispanic women in south Los Angeles. Cancer. 2011;117(16):3814–3823. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans. A biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Jackson JS. Discrimination, attribution, and racial group identification: implications for psychological distress among black Americans in the national survey of American life (2001–2003) Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(4):498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGuire LC, Strine TW, Okoro CA, et al. Modifiable characteristics of a healthy lifestyle in U.S. older adults with or without frequent mental distress: 2003 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(9):754–761. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180986125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng DM, Jeffery RW. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychol. 2003;22(6):638–642. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCann BS, Warnick GR, Knopp RH. Changes in plasma lipids and dietary intake accompanying shifts in perceived workload and stress. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(1):97–108. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steptoe A, Lipsey Z. Stress, hassles and variations in alcohol consumption, food choice, and physical exercise: a diary study. Br J Health Psychol. 1998;3(1):51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stetson BA, Rahn JM, Dubbert PM, et al. Prospective evaluation of the effects of stress on exercise adherence in community-residing women. Health Psychol. 1997;16(6):515–520. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.6.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dube SR, Caraballo RS, Dhingra SS, et al. The relationship between smoking status and serious psychological distress: findings from the 2007 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 1):68–74. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGuire LC, Strine TW, Vachirasudlekha S, et al. Modifiable characteristics of a healthy lifestyle and chronic health conditions in older adults with or without serious psychological distress, 2007 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 1):84–93. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and metaanalysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, et al. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, et al. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subar AF, Heimendinger J, Patterson BH, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake in the United States: the baseline survey of the five a day for better health program. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(5):352–360. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.5.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Craig C, Marshall A, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–S504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Wilson VB, editors. Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003. pp. 75–99. (NIH Publication No. 03-3745) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tofighi D, Mackinnon DP, Yoon M. Covariances between regression coefficient estimates in a single mediator model. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2009;62(Pt 3):457–484. doi: 10.1348/000711008X331024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castellsagué X, Muñoz N, De Stefani E, et al. Independent and joint effects of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on the risk of esophageal cancer in men and women. Int J Cancer. 1999;82(2):657–664. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<657::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loef M, Walach H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2012;55(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pelucchi C, Gallus S, Garavello W, et al. Cancer risk associated with alcohol and tobacco use: focus on upper aero-digestive tract and liver. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):193–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hart CL, Smith GD, Gruer L, Watt GCM. The combined effect of smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol on causespecific mortality: a 30 year cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:789–799. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holt CL, Roth DL, Clark EM, Debnam K. Positive selfperceptions as a mediator of religious involvement and health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. J Behav Med. 2012 Nov 11; doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9472-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dallman MF, Pecoraro NC, la Fleur SE. Chronic stress and comfort foods: self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(4):275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23(11–12):887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Austin AW, Smith AF, Parrerson SM. Stress and dietary quality in black adolescents in a metropolitan area. Stress & Health. 2009;25:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Epel E, Lapidus R, McEwen B, Brownell K. Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dube L, LeBel JL, Lu J. Affect assymetry and comfort food consumption. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(4):559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sims M, Wyatt SB, Gutierrez ML, et al. Development and psychometric testing of a multidimensional instrument of perceived discrimination among African Americans in the Jackson heart study. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(1):56–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bierman A. Does religion buffer the effects of discrimination on mental health? Differing effects by race. J Sci Study of Relig. 2006;45:551–565. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ellison CG, Musick MA, Henderson AK. Balm in Gilead: Racism, religious involvement, and psychological distress among African-American adults. J Sci Study of Relig. 2008;47:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]