Abstract

Keratoconus is the most common corneal ectatic disorder, the cause of which is largely unknown. Many factors have been implicated, and the ocular allergy is being one of them. The commonly proposed pathogenesis includes the release of inflammatory mediators due to eye rubbing which may alter the corneal collagen and lead to corneal ectasias. The onset of keratoconus is often early in cases associated with allergy and routine corneal topography may detect subtle forms of keratoconus. These cases may require early keratoplasty and are at an increased risk of having acute corneal hydrops. Surgical outcomes are similar to primary keratoconus cases. However, post-operative epithelial breakdown may be a problem in these cases. Control of allergy and eye rubbing is the best measure to prevent corneal ectasias in cases of ocular allergy.

Keywords: Keratoconus, ocular allergy, vernal keratoconjunctivitis

Keratoconus (KC) is a clinical term used to describe a condition in which the cornea assumes a conical shape because of thinning and protrusion.[1] The cause of this disease is still unknown. A positive association between KC and many conditions has been suggested and ocular allergy is one of them.[1] The various ocular allergic conditions that have been associated with KC includes vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), atopic keratoconjunctivitis and seasonal or perennial allergic keratoconjunctivitis.[1]

This review article attempts to study the association of ocular allergy with KC, and its implications on the management of KC.

Review of literature

Association between ocular allergy and keratoconus

The first reported association between ocular allergy and KC was described by Hilgartner in 1937.[1] The association was controversial with few studies reporting an association ranging from 7 to 35% while others did not show any relationship.[1] However, more recent studies have proved that there is a definite association between allergy and KC. Bawazeer et al., did a case control study and found a positive correlation between atopy, eye rubbing, and KC.[2] The Dundee University Scottish Keratoconus study was a prospective observational study of 200 consecutive patients presenting with KC.[3] They found atopic diseases including asthma in 23%, eczema in 14%, and hay fever in 30% of the KC patients. A study from India by Agrawal et al., evaluated 274 patients of KC and revealed a higher prevalence of allergy in these patients.[4] History of skin allergy, symptomatic ocular allergy, and asthma was seen in 26.6, 24.4, and 11.3% of patient's, respectively.[4]

Pathogenesis of ocular allergy and KC

KC is characterized by progressive stromal thinning as a result of increased expression of lysosomal and proteolytic enzymes, decreased concentration of protease inhibitors, which result in altered collagen configuration.[5,6] In allergic conjunctivitis when specific allergens are re-introduced into the body through the conjunctiva it reacts with the allergen specific IgE on the surface of mast cells or basophils, releasing vasoactive mediators. These mediators include inflammatory molecules like histamine, proteases, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) -alpha, and interleukin (IL).[1,3,4,5,6,8] Increased proteases, protease activity, and inflammatory molecules in the tears have been found to be relevant in the pathogenesis of KC. It has been proven that eye rubbing increases the level of tear matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-13, IL-6, and TNF- alpha even in normal subjects.[5,6] It has been hypothesized that this increase in protease activity may be further exacerbated during forceful eye rubbing seen in patients with allergic conjunctivitis, contributing to the development and progression of KC.

Role of early topography in ocular allergy

Since allergic disorders may be associated with early onset of KC, routine topography is indicated in such cases. Totan et al., studied the incidence of KC in VKC and found KC in 26.8% by quantitative evaluation of videokeratography (VKG) maps.[7] There was an increased incidence of KC with male gender, long standing disease, mixed/palpebral form, and advanced cornea lesions. They concluded that the higher incidence of KC in their study was due to early detection of mild KC with topography, stressing its importance in VKC patients. Léoni-Mesplié et al., studied the epidemiological aspects of KC in 49 children and compared these with 167 adult patients.[8] They found that allergy as well as eye rubbing are more in children compared to adults (allergy; 67.3 versus 47.3% in adults and eye rubbing; 91.8 versus 70% in adults). The authors recommend that corneal topography should be performed routinely in all young, allergic boys with the history of eye rubbing and recent-onset corneal astigmatism.

Role of ocular allergy in progression of KC

The effect of allergy on KC progression is controversial. Study by Lapid-Gortzak et al., evaluated the VKG findings in children with VKC (n = 40) versus those of healthy children (n = 36) and found that VKC patients have more abnormal corneal topographic patterns than non-VKC controls.[9] Barreto Jr et al., compared the slit-scanning topographic (SST) pattern of eyes with VKC (n =50) and normal eyes (54) and found that patients with VKC have more abnormal corneal SST patterns than controls.[10] A recent study by Taneja et al., evaluated KC progression in patients with VKC (22 eyes) using scanning slit topography and found that the rate of progression is not affected by the clinical course of VKC.[11]

Although allergy may not hasten KC progression, it definitely increases the chances of complications such as hydrops. In a study by Sharma et al., risk factors for keratoplasty and development of acute corneal hydrops in 120 consecutive KC patients were evaluated.[12] It was found that the patients of KC who had VKC required corneal transplant surgery earlier as compared to primary KC cases. In addition patients with younger age at onset, history of eye rubbing, and atopy had higher risk for developing corneal hydrops.[12]

Surgical outcome in cases of ocular allergy and KC

Egrilmez et al., evaluated the effect of VKC on clinical outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) in 33 eyes of KC.[13] They found that the clinical outcomes of PKP in eyes with KC and VKC is comparable to that in eyes with KC alone. However, complications such as loose sutures and steroid-induced cataracts were more common in cases with KC who had VKC. Wagoner et al., found that the graft survival, postoperative complications, and visual outcomes are comparable after PKP for KC in eyes with (n = 80) or without VKC (n = 384).[14] Thomas et al., compared the prevalence of endothelial rejection episodes and the probability of graft survival after initial and repeat PKP in patients with KC with (n = 66) and without (n = 102) atopy and found no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of endothelial graft rejection episodes or probability of graft survival.[15] Thus, it can be concluded that even though the final outcome may not differ after keratoplasty in cases of KC with or without ocular allergy, close follow up is required in the postoperative period to detect epithelial breakdown and steroid induced complications.

Personal experience

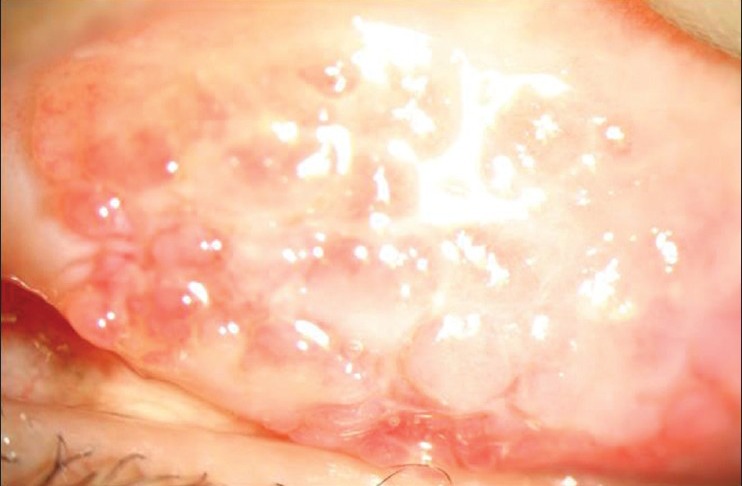

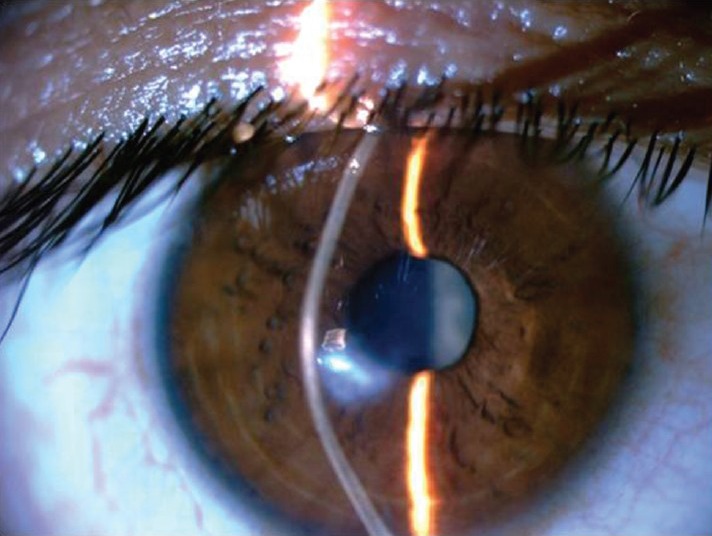

KC accounts for almost 90% of the lamellar keratoplasties and 5-10% of PKP are done at our center. VKC is the commonest type of association we find in our cases [Figs. 1 and 2]. These cases usually present early (in fact we have seen advanced KC cases at the age of 8 years) and show rapid progression. Patients with concomitant VKC may require early keratoplasty in cases of KC. Moreover, history of eye rubbing, VKC, and atopy increase the risk for developing acute corneal hydrops.[12] Post-operative course is also quite challenging in these cases. Chances of postoperative prolonged inflammation, epithelial breakdown and rapid healing with early loosening of sutures are commonly observed in these cases. Eye rubbing is the leading factor for early onset and rapid progression, hence all the cases of atopy or VKC must be advised to avoid eye rubbing. Prior to the surgery it must be ensured that the inflammation is controlled.

Figure 1.

Case of vernal keratoconjunctivitis with keratoconus having giant papillary conjunctivitis

Figure 2.

Same case as in Figure 1with keratoconus

Discussion

Ocular allergy is one of the important risk factors for KC. Subtle cases are unmasked on topography and hence all cases with ocular allergy should routinely be subjected to these investigations. Eye rubbing precipitates the onset and may also exacerbate the progression of KC; hence the patients should be advised to avoid eye rubbing. These cases are at an increased risk of complications such as acute corneal hydrops and may require early keratoplasty. The surgical outcome in cases of ocular allergy with KC is similar to the primary cases of KC, but a close follow up is required to avoid complications related to epithelial healing or steroid use.

Conclusion

To conclude ocular allergy has an important role in pathogenesis, disease progression, and the treatment outcome in cases of KC. Although a number of studies have proven this over the past decades, yet randomized controlled clinical trials on larger number of cases with longer follow up is required. Control of inflammation and avoidance of eye rubbing may offer the best means to prevent KC in these cases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Krachmer JH, Feder RS, Belin MW. Keratoconus and related noninflammatory corneal thinning disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:293–322. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bawazeer AM, Hodge WG, Lorimer B. Atopy and keratoconus: A multivariate analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:834–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weed KH, MacEwen CJ, Giles T, Low J, McGhee CN. The Dundee University Scottish Keratoconus study: Demographics, corneal signs, associated diseases, and eye rubbing. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:534–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal VB. Characteristics of keratoconus patients at a tertiary eye center in India. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011;6:87–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasubramanian SA, Mohan S, Pye DC, Willcox MD. Proteases, proteolysis and inflammatory molecules in the tears of people with keratoconus. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:e303–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balasubramanian SA, Pye DC, Willcox MD. Effects of eye rubbing on the levels of protease, protease activity and cytokines in tears: Relevance in keratoconus. Clin Exp Optom. 2013;96:214–8. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Totan Y, Hepşen IF, Cekiç O, Gündüz A, Aydin E. Incidence of keratoconus in subjects with vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A videokeratographic study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:824–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Léoni-Mesplié S, Mortemousque B, Mesplié N, Touboul D, Praud D, Malet F, et al. Epidemiological aspects of keratoconus in children. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2012;35:776–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lapid-Gortzak R, Rosen S, Weitzman S, Lifshitz T. Videokeratography findings in children with vernal keratoconjunctivitis versus those of healthy children. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:2018–23. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barreto J, Jr, Netto MV, Santo RM, José NK, Bechara SJ. Slit-scanning topography in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:250–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taneja M, Ashar JN, Mathur A, Vaddavalli PK, Rathi V, Sangwan V, et al. Measure of keratoconus progression in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis using scanning slit topography. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2013;36:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2012.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma R, Titiyal JS, Prakash G, Sharma N, Tandon R, Vajpayee RB. Clinical profile and risk factors for keratoplasty and development of hydrops in north Indian patients with keratoconus. Cornea. 2009;28:367–70. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818cd077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egrilmez S, Sahin S, Yagci A. The effect of vernal keratoconjunctivitis on clinical outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39:772–7. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagoner MD, Ba-Abbad R King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital Cornea Transplant Study Group. Penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus with or without vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2009;28:14–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818225dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas JK, Guel DA, Thomas TS, Cavanagh HD. The role of atopy in corneal graft survival in keratoconus. Cornea. 2011;30:1088–97. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31820d8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]