Abstract

The success of collagen cross-linking as a clinical modality to modify the clinical course in keratoconus seems to have fueled the search for alternative applications for this treatment. Current clinical data on its efficacy is limited and laboratory data seems to indicate that it performs poorly against resistant strains of bacteria and against slow growing organisms. However, the biological plausibility of crosslinking and the lack of effective strategies in managing infections with these organisms continue to focus attention on this potential treatment. Well-conducted experimental and clinical studies with controls are required to answer the questions of its efficacy in future.

Keywords: Collagen cross-linking, microbial keratitis, riboflavin, fungus, acanth

The combination of riboflavin and ultraviolet A light (UVA) exposure has been extensively used in collagen cross-linking (CXL) for the treatment of ectatic disorders of the cornea.[1] The antimicrobial effect of a similar photochemical reaction using riboflavin and UVA has been successfully exploited in the field of transfusion medicine for inactivation of various microorganisms in blood products.[2,3] This has inspired various groups to investigate the potential beneficial effects of CXL in the management of microbial keratitis. Herein, we attempt to put together the available evidence exploring the use of this modality in corneal infections.

Evidence from Laboratory Studies

Martins et al., first reported on the antimicrobial effect of riboflavin and UVA in vitro. An inhibition of growth was seen in both drug sensitive as well as drug resistant bacteria, but no effect was observed on the growth of Candida albicans.[4] Subsequently, Schrier et al., reported the effectiveness of a combination of riboflavin and UVA exposure for 30 minutes against Staphylococcus aureus as well as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[5] Makdoumi et al., tested the effects of riboflavin and UVA on bacterial suspensions in a fluid solution. They demonstrated that exposure for 60 minutes achieved a high degree of eradication of bacteria in vitro, whereas an exposure for 30 minutes achieved only a limited eradication.[6] In vitro and animal-model studies from multiple centers failed to show a beneficial effect of this treatment against Acanthamoeba.[7,8] Using a rabbit model, Galperin et al., demonstrated a reduction in severity and intensity of Fusarium solani keratitis using CXL.[9] In contrast, no effect of a similar treatment was observed on Fusarium solani and C. albicans isolates in an in vitro experiment performed by Kashiwabuchi et al.[10]

Clinical Reports

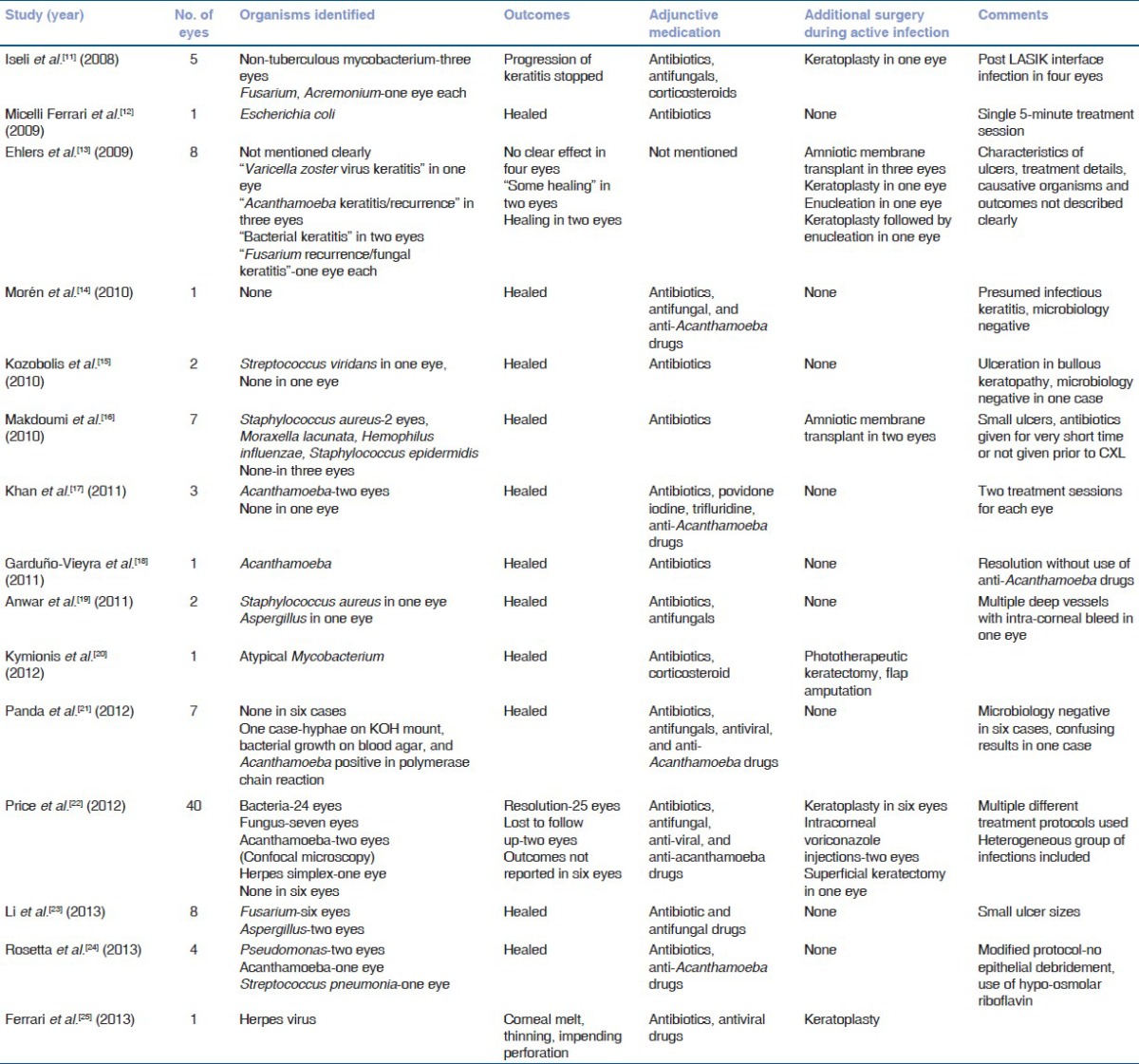

Studies on CXL in microbial keratitis are summarized in the Table 1. Most are small case series or single case reports. The modality has been studied in bacterial, fungal, viral, and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Except one, all are retrospective studies. Case selection appears arbitrary. A lack of homogeneity in terms of predisposing factors, clinical presentation and responsible organisms makes interpretation of results difficult. Some reported cases are presumed infections with negative microbiology. Others are diagnosed based on confocal microscopy. Treatment protocols range from a single 5-minute exposure of UVA to multiple sessions lasting up to 45 minutes. The concentration of riboflavin used has also been variable. Surgical procedures performed during active infection include keratoplasty, amniotic membrane transplantation, phototherapeutic keratectomy, flap amputation, intracorneal voriconazole injection, and enucleation. Outcome assessment is largely subjective, as a clear definition of what constitutes resolution or healing is missing in a majority of reports. Almost all results are confounded by the concurrent use of standard of care medical therapy. Though these reports seem to indicate that CXL may be an option in the treatment of infection, one cannot conclusively say it is effective as no control groups are available to compare against.

Table 1.

Cross-linking for microbial keratitis

Our Experience

We have carried out in vitro experiments to test the effects of a combination of riboflavin and UVA exposure on drug sensitive as well as multi-drug resistant bacteria, fungi, and Acanthamoeba. We used the standard Dresden protocol including 30 minutes of soaking time with 0.1% riboflavin in dextran and a 30-minute exposure of 3 mW/cm2 to 370 nm UV light. We conducted our experiments at LV Prasad Eye Institute in four arms, control, riboflavin only, UV only, and combined riboflavin + UV. We found the group with combined riboflavin and UV exposure had the greatest efficacy in reducing growth of the exposed microbes. In our experience, the treatment was most effective against bacterial isolates, with drug resistant strains requiring multiple exposures. We have not been able to demonstrate arrest the growth of fungi or Acanthamoeba in vitro with this treatment. Looking at the mixed published results as well as our own experimental data, we have been hesitant thus far to use CXL as a therapeutic option in cases of microbial keratitis. We have, however, managed cases treated elsewhere, which seemed to show equivocal results. We haven′t yet seen a patient with either fungal or Acanthamoeba keratitis where CXL helped in resolution of the infectious process following failure of specific therapy. We believe the next steps should be aimed at evaluating the response of the cornea with active keratitis to CXL and changes that occur over time rather than a cross-sectional observation. The ideal model for this kind of data would be an animal model of keratitis treated with CXL to observe changes in histology at various stages following the exposure.

Discussion

The promise of a simple, effective, and safe alternative to anti-microbial medication or keratoplasty is somewhat of a holy grail in the management of microbial keratitis. Harnessing the antimicrobial properties of UVA-activated riboflavin sounds biologically plausible. Putative mechanisms include the genome damage resulting from intercalation of activated flavins with nucleic acids and direct free radical insult to microbial deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA), in addition to the presumably increased resistance of the cornea to melting due to CXL-induced stiffening. Proof of principle exists, as demonstrated by the successful use of this technology in transfusion medicine.

In vitro studies show mixed results. The modality seems to be able to inhibit growth of bacteria, with drug-resistant strains requiring greater exposure time. Studies on fungi have conflicting results, and activity against Acanthamoeba seems even less convincing. Clinical reports are marred by poor study designs. Most cases reported include ulcers that would probably heal well with adequate duration of standard of care therapy. Ethical constraints preclude the use of CXL in isolation, without first using anti-microbial drugs. Potential concerns include endothelial damage in corneas that are already thin, as well as corneal melts and reactivation of viral keratitis. Most investigators have directly extrapolated the protocols using in CXL for keratoconus. Gray areas include optimum concentration of riboflavin and UVA exposure duration needed to combat microbes.

Based on available evidence, it is difficult to say whether CXL is effective in cases of microbial keratitis where we need it the most-drug resistant organisms, advanced keratitis and keratitis caused by organisms such as fungi and Acanthamoeba, which are refractory to conventional medical therapy. An ideal study would be prospective, with an adequate sample size, well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, appropriate outcome measures, and unbiased assessment as well as a robust interpretation of data. The preliminary results reported by Price et al., are part of an ongoing prospective, multi-center study.[22] We hope the eventual results would plug some of gaps in existent knowledge.

Conclusion

Parallels in transfusion medicine and data from laboratory experiments indicate the photochemical reaction used in CXL holds promise as a future therapeutic option for microbial keratitis. Clinical reports are inconsistent and difficult to interpret. Well-designed studies investigating the safety and efficacy of this modality in appropriately chosen cases of microbial keratitis are sorely needed.[25]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Chan E, Snibson GR. Current status of corneal collagen cross-linking for keratoconus: A review. Clin Exp Optom. 2013;96:155–64. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodrich RP. The use of riboflavin for the inactivation of pathogens in blood products. Vox Sang. 2000;78(Suppl 2):S211–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruane PH, Edrich R, Gampp D, Keil SD, Leonard RL, Goodrich RP. Photochemical inactivation of selected viruses and bacteria in platelet concentrates using riboflavin and light. Transfusion. 2004;446:877–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martins SA, Combs JC, Noguera G, Camacho W, Wittmann P, Walther R, et al. Antimicrobial efficacy of riboflavin/UVA combination (365 nm) in vitro for bacterial and fungal isolates: A potential new treatment for infectious keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3402–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrier A, Greebel G, Attia H, Trokel S, Smith EF. In vitro antimicrobial efficacy of riboflavin and ultraviolet light on Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:S799–802. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090813-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makdoumi K, Bäckman A, Mortensen J, Crafoord S. Evaluation of antibacterial efficacy of photo-activated riboflavin using ultraviolet light (UVA) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;248:207–12. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashiwabuchi RT, Carvalho FRS, Khan YA, de Freitas D, Foronda AS, Hirai FE, et al. Assessing Efficacy of combined riboflavin and uv-a light (365 nm) treatment of Acanthamoeba trophozoites. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9333–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Buey MA, Cristóbal JA, Casas P, Goñi P, Clavel A, Mínguez E, et al. Evaluation of in vitro efficacy of combined riboflavin and ultraviolet a for Acanthamoeba isolates. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galperin G, Berra M, Tau J, Boscaro G, Zarate J, Berra A. Treatment of fungal keratitis from Fusarium infection by corneal cross-linking. Cornea. 2012;31:176–80. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318221cec7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashiwabuchi RT, Carvalho FR, Khan YA, Hirai F, Campos MS, McDonnell PJ. Assessment of fungal viability after long-wave ultraviolet light irradiation combined with riboflavin administration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;251:521–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iseli HP, Thiel MA, Hafezi F, Kampmeier J, Seiler T. Ultraviolet A/riboflavin corneal cross-linking for infectious keratitis associated with corneal melts. Cornea. 2008;27:590. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318169d698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micelli Ferrari T, Leozappa M, Lorusso M, Epifani E, Micelli Ferrari L. Escherichia coli keratitis treated with ultraviolet A/riboflavin corneal cross-linking: A case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:295–7. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehlers N, Hjortdal J, Nielsen K, Søndergaard A. Riboflavin-UVA treatment in the management of edema and nonhealing ulcers of the cornea. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:S803–6. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090813-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morén H, Malmsjö M, Mortensen J, Ohrström A. Riboflavin and ultraviolet a collagen crosslinking of the cornea for the treatment of keratitis. Cornea. 2010;29:102–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31819c4e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozobolis V, Labiris G, Gkika M, Sideroudi H, Kaloghianni E, Papadopoulou D, et al. UV-A collagen cross-linking treatment of bullous keratopathy combined with corneal ulcer. Cornea. 2010;29:235–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a81802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makdoumi K, Mortensen J, Crafoord S. Infectious keratitis treated with corneal crosslinking. Cornea. 2010;29:1353–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181d2de91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan YA, Kashiwabuchi RT, Martins SA, Castro-Combs JM, Kalyani S, Stanley P, et al. Riboflavin and ultraviolet light A therapy as an adjuvant treatment for medically refractive acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garduño-Vieyra L, Gonzalez-Sanchez CR, Hernandez-Da Mota SE. Ultraviolet-a light and riboflavin therapy for acanthamoeba keratitis: A case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2:291–5. doi: 10.1159/000331707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anwar HM, El-Danasoury AM, Hashem AN. Corneal collagen crosslinking in the treatment of infectious keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1277–80. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S24532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kymionis GD, Kankariya VP, Kontadakis GA. Combined treatment with flap amputation, phototherapeutic keratectomy, and collagen crosslinking in severe intractable post-LASIK atypical mycobacterial infection with corneal melt. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:713–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panda A, Krishna SN, Kumar S. Photo-activated riboflavin therapy of refractory corneal ulcers. Cornea. 2012;31:1210–3. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823f8f48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price MO, Tenkman LR, Schrier A, Fairchild KM, Trokel SL, Price FW., Jr Photoactivated riboflavin treatment of infectious keratitis using collagen cross-linking technology. J Refract Surg. 2012;28:706–13. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20120921-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Jhanji V, Tao X, Yu H, Chen W, Mu G. Riboflavin/ultravoilet light-mediated crosslinking for fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:669–71. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosetta P, Vinciguerra R, Romano MR, Vinciguerra P. Corneal collagen cross-linking window absorption. Cornea. 2013;32:550–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318259c9bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrari G, Iuliano L, Viganò M, Rama P. Impending corneal perforation after collagen cross-linking for herpetic keratitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:638–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]