Abstract

Keratoconus is a progressive corneal ectasia, which can be managed both by conservative measures like glasses or contact lenses in non-progressive cases or surgical procedures like collagen crosslinking (CXL) with or without adjuvant measures like intrastromal corneal rings segments (ICRS) or topography guided ablation. Various kinds of ICRS are available to the surgeon, but it is most essential to be able to plan the implantation of the ring to optimize outcomes.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the visual outcome and progression in patients of keratoconus implanted with ICRS.

Materials and Methods:

Two different types of ICRS-Intacs (Addition Technology) and Kerarings (Mediphacos Inc.) were implanted in 2 different cohorts of patients and were followed-up to evaluate the outcome of the procedure. All patients underwent a complete ocular examination including best spectacle corrected visual acuity, slit lamp examination fundus examination, corneal topography and pachymetry. The ICRS implantation is done with CXL to stop the progression of the disease. Improvement in uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best spectacle corrected visual acuity and topographic changes were analyzed.

Results:

A significant improvement in keratometry and vision was seen in both groups.

Conclusion:

ICRS have been found to reduce corneal irregularity and flatten keratometry with improvement in UCVA and best corrected visual acuity.

Keywords: Intrastromal corneal rings segments, keratoconus, treatment

Keratoconus is an ectatic disease of the cornea characterized by localized progressive thinning and forward protrusion of the cornea.[1] There have been several management options discussed for keratoconus including collagen crosslinking (CXL), topography guided ablation, intrastromal corneal ring segment (ICRS) implantation and keratoplasty.[2,3,4,5,6,7] Both the surgeon and the patient are likely to be reluctant to opt for a keratoplasty when the cornea is clear because of the possible post-operative complications. These potential complications could be avoided by a relatively less invasive surgical intervention like ICRS implantation.[8,9,10] ICRS have been found to be useful in correcting ectatic corneal disorders by reducing corneal steepening and decreasing irregular astigmatism thus potentially improving the visual acuity. It can also be considered as an option to defer if not eliminate, the need for keratoplasty in these patients.[1,7]

Improvement in visual acuity and refraction after ICRS implantation is accomplished by a shortening of collagen lamellae along the arc length of the ring. There is a redistribution of corneal stress due to the change in the shape of the cornea after implantation of ICRS.[7,11,12]

Intracorneal Ring Models

There are different types of ICRS available: (1) Intacs (Addition Technology Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) (2) Kerarings (Mediphacos Inc.) (3) Bisantis Intrastromal segmented perioptic implants (Opticon 2000 SpA and SolekoSpA).

Intacs segments

Intacs segments are made of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and are available in various sizes with two broad categories of regular (R) rings and steep keratometry (SK) rings with a circumference arc length of 150°. The (R) rings have a hexagonal transverse cross-section and a conical longitudinal section with an external diameter of 8.10 mm and an internal diameter 6.77 mm. The refractive effect is modulated by the thickness of the rings, which are available from 0.25 mm to 0.50 mm in 0.05 mm increments.[3] The Intacs SK has an inner diameter of 6.0 mm and an oval cross-section shape and is more effective in more advanced keratoconus with SK. SK rings are available in thickness of 0.40 mm, 0.45 mm, 0.50 mm and 0.210 mm.[13] The smaller diameter has a larger effect on corneal flattening and the elliptical design reduces halos.[14] All these rings can be used as a single insert or in combination.

Kerarings

Keraring is an orthosis implanted in the corneal stroma. It acts upon corneal tissue by altering its central curvature and shape, thus reducing or eliminating morphological irregularities and existing myopia and astigmatism. They are available as 160° segments made of PMMA. They are triangular in cross-section with a 600 micron base and an apical diameter of 5 mm. They come in variable thickness (0.15, 0.20, 0.25, 0.30 and 0.35 mm) in 0.05 mm steps.[5]

The change in the corneal structure induced by any ICRS can be roughly estimated by the Barraquer thickness law; therefore, the outcome achieved is directly proportional to the thickness of the ICRS and inversely proportional to its diameter.[1,7,11]

Channel dissection methods for ICRS

Channel creation for implantation of the ICRS can be done by 2 methods – manual technique or using a femtosecond laser under topical anesthesia. Depth of the channel is kept at 75-80% of maximum pachymetry in the area of ring implantation.

Even though, the manual technique using a diamond blade and a metal channel dissector has good results in terms of outcome, the advent of the femtosecond laser has made the procedure safer with very high accuracy of implantation. The laser used is a femtosecond photo disruptive laser.[7,13,15] Advantages of Femtosecond laser over conventional tunnel creation are less discomfort to patient and better patient cooperation, faster creation of tunnels, precise control of tunnel depth, width and centration, minimal tissue disturbance and faster post-operative recovery.

Incision

The location of incision is usually guided by the steep topographic axis, which may not be consistent with the axis of manifest refraction, but some surgeons have been known to make the incision at 180° meridian irrespective of the axis.[14]

Combining ICRS with crosslinking

It is recommended to follow the intrastromal ring implantation with corneal CXL to prevent progression of the keratoconus and amplify the flattening effect of the ring segments.[13]

Materials and Methods

Intacs group: 61 eyes of 58 patients (single surgeon RS).

Kerarings group: 89 eyes of 73 patients (single surgeon SG).

Inclusion criteria

Moderate to severe keratoconus with pachymetry greater than 450 microns in the zone of ring implantation with disabling visual acuity, intolerance to contact lens/spectacle correction and patients with progressing keratoconus were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with pachymetry less than 450 microns in the zone of ring implantation, post hydrops, corneal scarring, glaucoma, retinal diseases, severe atopic disease, local active infection, autoimmune or immunodeficiency syndrome or patients with recurrent corneal erosion syndrome or corneal dystrophy were excluded from the study. All patients underwent a complete ocular examination including uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best spectacle corrected visual acuity, slit lamp examination of anterior segment, intraocular pressure measurement and a detailed fundus examination.

Cornealtopography, keratometry and pachymetry assessed by Pentacam (Oculus, GmBH, Wetzlar, Germany) and Orbscan II (Bausch and Lomb Inc, Rochester, NY, USA) was done for all patients.

Planning the keraring to be implanted

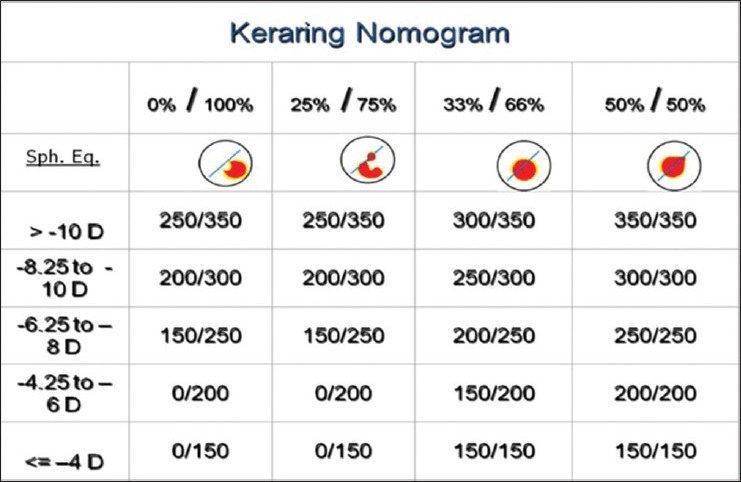

Kerarings were implanted as per the keraring nomogram [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Nomogram for kerarings

Planning the intacs ring to be implanted

Although there is extensive work done in this area, we have found that many available nomograms do not usually explain the possible indications for each type of ring or the stepwise planning for the Intacs ring insertion. To this end, we have been trying to frame a planning protocol, which takes into account the centration of the cone, the spherical equivalent and the keratometry. The centration of the cone is based on the percentage of the cone within 3 mm zone on the pentacam posterior elevation map. A centered cone has more than 50% of the cone within the 3 mm zone while a decentered cone has more than 50% of the cone outside it. A centered cone requires symmetric rings to be implanted while a decentered cone should be implanted with asymmetric or a single ring depending on the extent of decentration. The steepness of the keratometry decides whether we choose a regular Intacs ring or an SK ring with a mean K of 55D being the cut-off value and the size of the ring is decided as per the mean spherical refractive equivalent (MRSE); the higher MRSE needs a thicker ring. This simplifies choosing the appropriate Intacs ring for implantation to achieve a more predictable and improved outcome post procedure.

Results of Intacs Ring Implantation

The average UCVA improved from 0.10 ± 0.05 pre-operatively to 0.25 ± 0.08 at 1 year post-operatively (P < 0.05). The average best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) improved from 0.61 ± 0.14 pre-operatively to 0.73 ± 0.17 post-operative 1 year (P < 0.05) [Fig. 2]. The improvement in average MRSE was from –6.11 ± 4.26 to –2.42 ± 1.58 (P < 0.001). Average K reduced from 52.5 ± 5.13 to –48.30 ± 4.12 (P < 0.05) [Fig. 3].

Figure 2.

Change in uncorrected visual acuity and best corrected visual acuity from pre-operative to 1 year post-operative Intacs + collagen crosslinking

Figure 3.

Flattening of keratometry from pre-operative to 1 year post-operative Intacs + collagen crosslinking

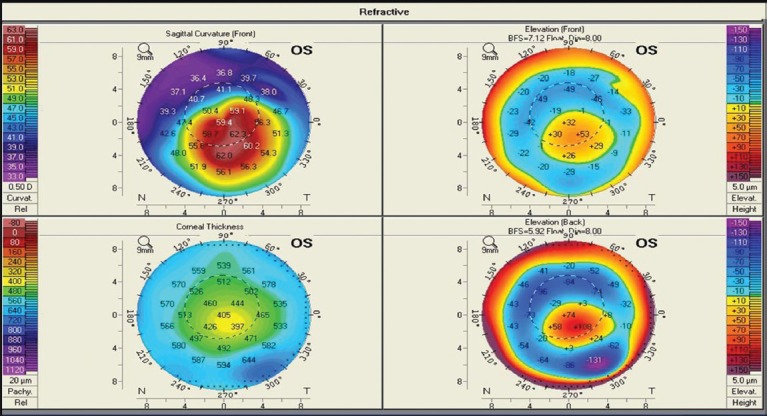

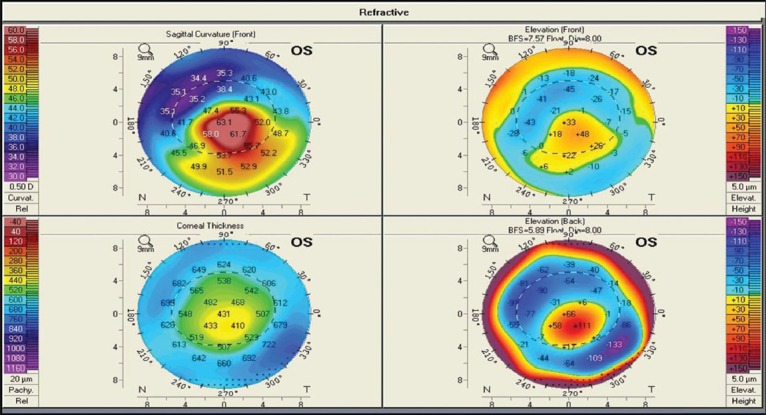

We would like to highlight a case example showing a good outcome post-surgery.

Case – 28-year-old male with bilateral keratoconus, with the left eye pre-operative K1 54.1, K2 58.7, partly decentered cone on pentacam [Fig. 4] and spherical equivalent –4.0. Patient was planned for the left eye asymmetric Intacs SK rings implantation (0.45 and 0.21 mm) post-operative pentacam scan showed a marked flattening with K1 being 51.2 and K2 54.5 [Fig. 5].

Figure 4.

Pre-operative pentacam map showing partially decentered cone

Figure 5.

Post-operative pentacam map post Intacs and crosslinking showing better centration of the cone and flattening on sagittal curvature

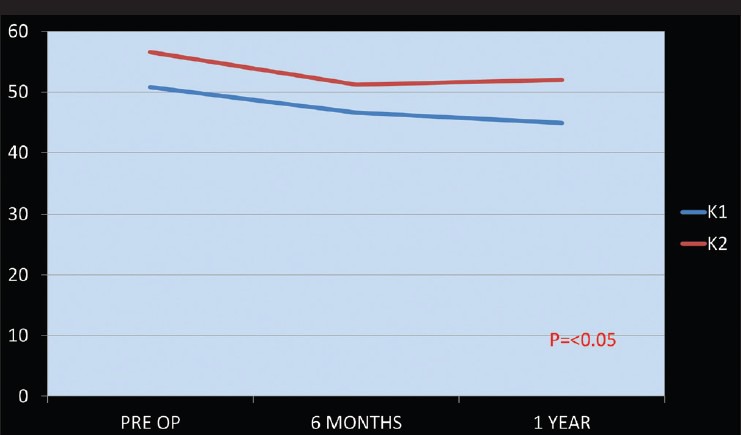

Results of Kerarings Implantation

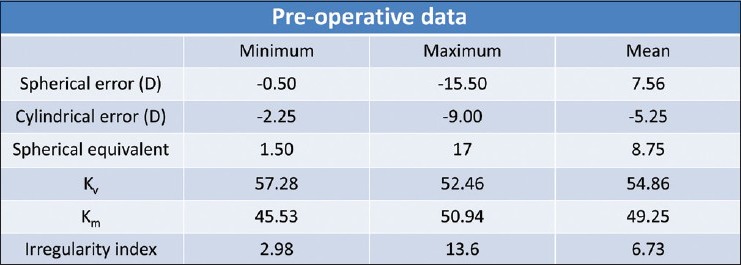

Pre-operatively the mean spherical equivalent was –8.75 ± 2.25, mean cylindrical error was –5.25 ± 2.37, the mean K (vertical) pre-operative was 54.86 ± 2.19 and K (horizontal) was 49.25 ± 2.75. The irregularity index at 3 mm zone pre-operative was 6.73 ± 2.94 [Fig. 6]. Post-operatively at 12th month follow-up, the mean spherical equivalent was −2.56 ± 1.13, mean cylindrical error was –2.48 ± 1.57, the mean K (vertical) post Kera Ring Implant was 48.78 ± 2.75 and K (horizontal) was 45.56 ± 2.15. The irregularity index at 3 mm zone post-operative was 5.98 ± 2.32 [Fig. 7]. Reduction noted in Sim K, Min K, Max K and irregularity index were statistically significant. On statistical analysis of UCVA, all eyes in the study had a vision better than 6/36 with 16 eyes having 6/6. Analysis of BCVA showed all eyes had a vision better than 6/12 with 26 eyes having a vision of 6/6 [Fig. 8]. Post-operatively the number of patients with UCVA of 6/6 increased from 16 to 28 (31.4%).

Figure 6.

Pre-operative data of patients for whom kerarings were implanted

Figure 7.

Post-operative data of patients for whom kerarings were implanted

Figure 8.

Lines of improvement in visual acuity after kerarings implantation

Discussion

The planning for insertion of the ICRS is extremely crucial in deciding the outcome of the surgery. The rings can be used as single inserts or as a combination of symmetric or asymmetric rings. Some earlier studies related to ICRS described uniform placement of symmetric or asymmetric ring for all keratoconus patients.[16]

Various parameters have been considered in the planning of ICRS placement. Ertan and Colin[13] Wachler et al.,[17] Kanellopoulos et al.[18] and Zare et al.[10] all used the spherical equivalent of the patient for insertion of symmetric rings of 0.4 or 0.45 mm thickness. They all showed an improvement in UCVA, BCVA and mean K. Colin et al.[19] and Ertan et al.[20] used 0.45/0.25 mm asymmetric rings uniformly for all patients. Single ring implantation was carried out in the study conducted by Chan et al.[21] which established the effectiveness of ICRS with CXL as against ICRS alone. Sharma and Wachler[22] did a study on comparison of single versus double ring implantation for post- laser in situ keratomileusis ectasia. They found a more dramatic improvement in the single segment group. Rabinowitz et al.[23] however, conducted a similar study and did not find any statistically significant difference between the two groups. Nomograms, which included the morphology of cones were those by Colin,[24] which took into consideration the location of the cone and asymmetric astigmatism induced by the keratoconus. Their description of the cone was either global or central for which they used symmetrical rings; and as mildly, moderately or highly asymmetric for which they used asymmetric rings. Alió et al.[25] advised asymmetric or single ring implantation based on the layout of the cone on topography. Inferior cones not going beyond the 180° meridian got a single ring while those exceeding that limit were implanted with symmetric double rings. Torquetti et al.[1] also took into account the type of cone on topography and the distribution of ectasia based on the percentage of cone on either side of the midline. Even in this study, planning of the ring placement based on the morphology of the cone in addition to the patient's refraction gave superior outcomes in terms of the flattening in keratometry and visual acuity. Coskunseven et al.[26] studied the effect of femtolaser assisted kera ring implantation in keratoconic patients and found that there was a statistically significant reduction in the spherical equivalent refractive error compared with pre-implantation error. The use of the femtosecond laser in corneal tunnel creation made the procedure faster, easier and more comfortable for the patient. However, the main advantage of femtosecond laser assisted channel creation over the mechanical technique seems to be the precise depth of implantation. From the published data and our experience, the safety of the procedure seems to be very high.[15] In comparison with other studies of intracorneal rings implantation with mechanical devices, there was a significant reduction of complication rate. The advantages of ICRS are that the procedure is reversible and the refractive result can be potentially be titrated by replacing the segment with another ring segment of a different thickness. The procedure maintains the prolate shape of the cornea and the ring segments do not affect the central cornea thus reducing the incidence of glare and halos.[27]

Conclusion

ICRS is safe, reversible, minimally invasive procedure with good visual and refractive outcomes. It is an extremely good option for treatment of keratoconus and has shown excellent outcomes in terms of the change in topography, the visual acuity and tolerance to contact lenses. Planning for the appropriate ring to be implanted is probably as important as the surgical technique to ensure a good outcome and a happy patient. It is essential to keep in mind the various factors that can influence the response to treatment like the location of the cone, the severity of the keratoconus and the biomechanics of the eye before planning the procedure.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Torquetti L, Berbel RF, Ferrara P. Long-term follow-up of intrastromal corneal ring segments in keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1768–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ertan A, Kamburoğlu G. Intacs implantation using a femtosecond laser for management of keratoconus: Comparison of 306 cases in different stages. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:1521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barraquer JI. Modification of refraction by means of intracorneal inclusions. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1966;6:53–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald MB, Kaufman HE, Durrie DS, Keates RH, Sanders DR. Epikeratophakia for keratoconus. The nationwide study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1294–300. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210048024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buratto L, Belloni S, Valeri R. Excimer laser lamellar keratoplasty of augmented thickness for keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 1998;14:517–25. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19980901-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch DD. Refractive surgery for keratoconus: A new approach. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:1099–100. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekundo W, Stevens JD. Surgical treatment of keratoconus at the turn of the 20th century. J Refract Surg. 2001;17:69–73. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20010101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson RJ, Pingree M, Ridges R, Lundergan ML, Alldredge C, Jr, Clinch TE. Penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: A long-term review of results and complications. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:987–91. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordan LT. Keratoconus: Diagnosis and treatment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37:51–63. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199703710-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zare MA, Hashemi H, Salari MR. Intracorneal ring segment implantation for the management of keratoconus: Safety and efficacy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1886–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burris TE, Ayer CT, Evensen DA, Davenport JM. Effects of intrastromal corneal ring size and thickness on corneal flattening in human eyes. Refract Corneal Surg. 1991;7:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dauwe C, Touboul D, Roberts CJ, Mahmoud AM, Kérautret J, Fournier P, et al. Biomechanical and morphological corneal response to placement of intrastromal corneal ring segments for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1761–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ertan A, Colin J. Intracorneal rings for keratoconus and keratectasia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1303–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan MI, Injarie A, Muhtaseb M. Intrastromal corneal ring segments for advanced keratoconus and cases with high keratometric asymmetry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratkay-Traub I, Ferincz IE, Juhasz T, Kurtz RM, Krueger RR. First clinical results with the femtosecond neodynium-glass laser in refractive surgery. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:94–103. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20030301-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kymionis GD, Siganos CS, Tsiklis NS, Anastasakis A, Yoo SH, Pallikaris AI, et al. Long-term follow-up of intacs in keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:236–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wachler BS, Christie JP, Chandra NS, Chou B, Korn T, Nepomuceno R. Intacs for keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1031–40. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(03)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanellopoulos AJ, Pe LH, Perry HD, Donnenfeld ED. Modified intracorneal ring segment implantations (INTACS) for the management of moderate to advanced keratoconus: Efficacy and complications. Cornea. 2006;25:29–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000167883.63266.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colin J, Cochener B, Savary G, Malet F, Holmes-Higgin D. INTACS inserts for treating keratoconus: One-year results. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1409–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ertan A, Kamburoğlu G, Bahadir M. Intacs insertion with the femtosecond laser for the management of keratoconus: One-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:2039–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan CC, Sharma M, Wachler BS. Effect of inferior-segment intacs with and without C3-R on keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma M, Wachler BS. Comparison of single-segment and double-segment Intacs for keratoconus and post-LASIK ectasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:891–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabinowitz YS. Intacs for keratoconus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:279–83. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3281fc94a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colin J. European clinical evaluation: Use of Intacs for the treatment of keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alió JL, Shabayek MH, Belda JI, Correas P, Feijoo ED. Analysis of results related to good and bad outcomes of intacs implantation for keratoconus correction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:756–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coskunseven E, Kymionis GD, Tsiklis NS, Atun S, Arslan E, Jankov MR, et al. One-year results of intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation (KeraRing) using femtosecond laser in patients with keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:775–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubaloglu A, Sari ES, Cinar Y, Koytak A, Kurnaz E, Ozertürk Y. Intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation for the treatment of keratoconus. Cornea. 2011;30:11–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e2cf57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]