Abstract

The brain basis for music knowledge and the effects of disease on music cognition are poorly understood. Here we present evidence for relatively preserved knowledge of music in a musically untrained patient with semantic dementia and characteristic asymmetric anterior temporal lobe atrophy. Our findings suggest that music is partly separable neuropsychologically and anatomically from other semantic domains, with implications for the clinical management of patients with brain disease.

Semantic dementia (SD) is a clinical syndrome that is characterised by progressive, selective breakdown of verbal and non-verbal (multimodal) knowledge systems. The disorder is associated with focal brain atrophy predominantly involving the anterior left temporal lobe1 and is distinct clinically, anatomically and pathologically from Alzheimer disease. Music is a specialised dimension of non-verbal cognition;2 – 4 however, the effects of SD on music processing have not been studied. Here, we describe relative preservation of musical knowledge in a patient with SD.

A 56-year-old right-handed female book keeper exhibited insidiously progressive deterioration of language, manifesting as reduced vocabulary and empty, circumlocutory but grammatical speech. The patient subsequently developed impaired recognition of familiar faces and everyday objects, executive dysfunction and behavioural changes including sweet tooth and mild disinhibition. She became increasingly interested in music, listening to CDs of popular songs for many hours each day and singing or humming along to these songs and music on television. The patient had no formal musical training and had never played an instrument.

Brain MRI and general neuropsychological assessments were undertaken 3 years and 5 years after clinical onset. Brain MRI initially showed selective atrophy of the anterior left temporal lobe predominantly involving the temporal pole and the fusiform, inferior and middle temporal gyri—typical of SD. Subsequently, there was extension of the atrophy to involve the right antero-inferior temporal lobe and orbitofrontal cortex.

At the first neuropsychological assessment, the patient displayed predominant impairments of naming and of single-word comprehension (both <5th percentile) with surface dyslexia (supplementary table 1 online). By the time of the second assessment, the patient had widespread deficits with profound impairment of both verbal and non-verbal semantic memory (at floor on Synonyms, Famous Faces recognition and easy British Picture Vocabulary Scale rests).

Musical memory was assessed 5 years after clinical onset. The patient was asked to continue singing or humming familiar tunes after hearing a brief introduction. Forty tunes were chosen (supplementary table 2 online): 10 popular songs of the 1960s and 1970s to which she listened regularly (identified by her family), 10 common nursery rhymes and 20 other tunes well-known to British subjects (e.g. Auld Lang Syne, Jerusalem). The first four to eight musical bars of each tune were presented, whereas for the popular songs and nursery rhymes the first line was sung (with lyrics) by one of the authors (JH). For the ‘British’ tunes, another of the authors (RO) played the introduction on the piano as a single line melody without harmony or vocal accompaniment. Melodies were presented in a key other than the original. Responses were recorded for subsequent analysis. The ‘British’ tunes were also administered to three healthy non-musician female control subjects (ages 64–72) with no history of tone deafness, who were asked to demonstrate recognition of the tunes.

To compare musical and verbal performance, the patient was assessed on verbal tasks analogous to the musical continuations (supplementary table 2). She was presented with spoken first lines of the pop songs and nursery rhymes, and five sentences requiring high frequency terminal words (e.g. ‘She posted the letter without a…[stamp]’) and six common idioms (e.g. ‘Bread and …[butter]’).

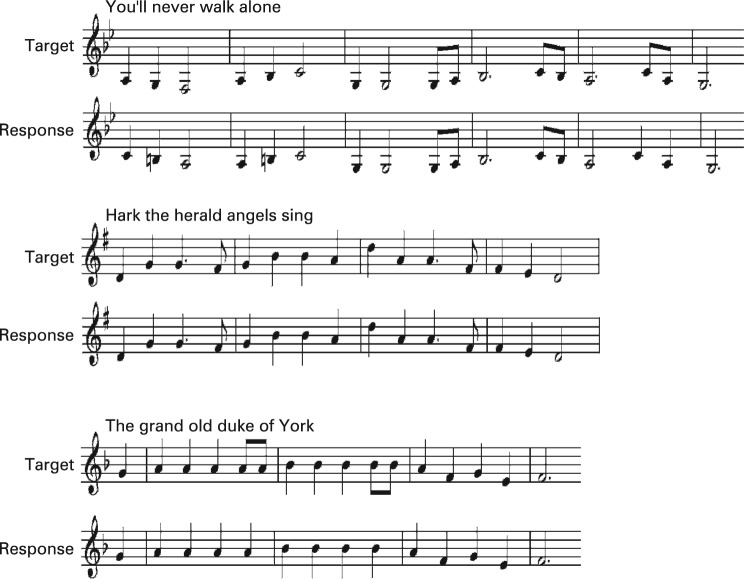

The patient sang an accurate (unambiguous) continuation of the melody for 25 of the 40 tunes (figure 1; supplementary table 2): 7 of the 10 pop songs, 6 of the 10 nursery rhymes and 12 of the 20 ‘British’ tunes. Her performance on ‘British’ tunes was comparable or somewhat inferior to recognition performance of the older control subjects (mean control score 13 out of 20, range 12–16). The patient generally sang the tunes to the syllable ‘do’, producing accompanying lyrics for three pop songs (average 5.3 words) and five nursery rhymes (average 1.6 words). In those cases where the patient did not continue the tune correctly, she produced an alternative continuation that was meaningful melodically (ending on the tonic or the dominant of the key) or rhythmically (ending with a long or stressed final note). This performance contrasted with her gravely impaired verbal skills. She was able to provide a verbal continuation for only 5 of the 20 spoken song lyrics and nursery rhymes (between 1 and 3 words in these cases) and was unable to provide any high frequency sentence or idiom completions.

Figure 1.

Examples of musical continuations provided by the patient for pop songs, well-known “British” tunes and nursery rhymes. For each tune, the “target” melody (the correct continuation) is shown above and the patient’s response has been transcribed below.

This case suggests that knowledge of music may be disproportionately preserved in SD compared with other modalities of knowledge. Debate continues regarding the nature of musical knowledge and the relative contributions of semantic, episodic and procedural factors.2 – 4 Indeed, episodic and procedural (motor activity) memory are often spared in SD and might support some kinds of musical memory. It is unlikely, however, that our patient’s ability to continue familiar tunes depended entirely on episodic recall, since the tunes were presented in a non-standard form with both instrumental context (sung or played on piano) and harmonic context (transposed in key) altered. This suggestion is consistent with other evidence that knowledge of familiar music does not depend on episodic memory.2 3 It is also unlikely that our patient’s performance was driven solely by procedural memory: only around a quarter of the tunes were sung regularly by the patient, and half were presented on the piano, which she had never played. Rather than reactivating an episode from memory or a stored motor programme, the continuation of the tunes required, therefore, active translation of heard music into a new vocal output. We argue that this translation process is mediated by brain knowledge stores (semantic memory) for music. Besides retained knowledge of particular songs, the patient’s ability to supply alternative musical continuations in accord with the melodic and rhythmic ‘rules’ of Western music suggests that she retained general implicit knowledge about musical structure.

The present case supports previous studies suggesting that knowledge of music has brain substrates that are partly separable from those mediating other forms of verbal and nonverbal knowledge.3 4 Functional imaging evidence in normal individuals suggests that semantic memory for familiar tunes is mediated by a distributed network that includes the bilateral medial and orbital frontal cortex, the left angular gyrus and the left anterior middle temporal gyrus.3 We do not claim that musical semantic memory was entirely normal in our patient; however, the present findings suggest that the anterior left temporal lobe may be less critical for musical than for other forms of semantic memory. We propose that musical knowledge may be differently represented in the brain because musical ‘objects’ (such as melodies) are essentially abstract, unlike visual objects, environmental sounds and other objects of sensory perception. This differentiation could be functional as well as anatomical: it is likely that factors such as emotional content, arousal and context have an important influence on the encoding and retrieval of musical versus other kinds of memories. Moreover, knowledge for different kinds of musical information may have distinct substrates.4 Relative sparing of musical knowledge may contribute to musicophilia in patients with frontotemporal lobar degenerations5 and may have implications for the use of music therapy and music-based cognitive rehabilitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for her participation. Informed consent was obtained for publication of the person’s details in this report.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Funding: This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and the Alzheimer’s Research Trust. JDW is supported by a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship. This work was undertaken at University College London, London, UK, which receives a proportion of funding from the Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. The Dementia Research Centre is an Alzheimer’s Research Trust Co-ordinating Centre.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bozeat S, Lambon Ralph MA, Patterson K, et al. Non-verbal semantic impairment in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia 2000;38:1207–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haslam C, Cook M. Striking a chord with amnesic patients: evidence that song facilitates memory. Neurocase 2002;8:453–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Platel H, Baron JC, Desgranges B, et al. Semantic and episodic memory of music are subserved by distinct neural networks. Neuroimage 2003;20:244–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steinbeis N, Koelsch S. Comparing the processing of music and language meaning using EEG and FMRI provides evidence for similar and distinct neural representations. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boeve BF, Geda YE. Polka music and semantic dementia. Neurology 2001;57:1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]