Abstract

Background:

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the major causes of death and disability. Apoptosis after TBI contributes significantly to the final extent of tissue damage. The Bcl-2 family proteins are important apoptosis modulators which increased in injured neurons. Bcl-2 has shown an antiapoptotic effect in rats and mice. ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 is a synthetic short fragment of ACTH devoid of hormonal effects and has neuromodulatory properties. ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 has been shown to increase levels of Bcl-2 and BDNF in vitro as well as in vivo. It has been postulated that ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 will result in improved clinical outcome and reduce hospital length of stay. The goal of this study is to compare the effect of standard therapy only with standard therapy and ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10, the increase of Bcl-2, and clinical outcome with reduction of hospital stay.

Materials and Methods:

Subjects of moderate head injury (MHI) with no indication of surgery were taken consecutively (n = 40) and separated into two groups: standard treatment only and standard treatment combined with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10. Blood samples were taken on day 1 and day 5 from each subject for measurements of Bcl-2 concentration. Barthel Index and MMSE were measured, at discharge and hospital length of stay was noted.

Results:

Forty subjects have been involved in this study, three subjects died in the standard therapy group, and one subject in ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group. Bcl-2 serum level in standard therapy was 1.39 ± 0.75 ng/mL on day 1 and 1.48 ± 0.77 ng/mL on day 5. After treatment with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10, Bcl-2 level was 1.39 ± 0.70 ng/mL on day 1 and 3.70 ± 1.02 ng/mL on day 5. The serum Bcl-2 concentration was significantly increased with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 therapy with shorter hospital length of stay (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 increased serum Bcl-2 levels and reduced hospital length of stay significantly compared with standard therapy alone.

Keywords: ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10, Barthel Index, Bcl-2 concentration, hospital length of stay, MMSE, moderate head injury

Introduction

Head injury caused by traffic accidents has a high prevalence. Data from the Department of Neurosurgery, H. Adam Malik Hospital Medan, showed that the total of head injury cases in 2010 were 1627 cases, mild head injury 1021 cases, moderate head injury (MHI) 444 cases, and severe head injury 162 cases. Of the total, 274 cases (16.8%) were surgical cases. Some of the moderate and severe head injury cases have a high mortality and high morbidity causing the loss of productivity.[1]

Brain injury can be classified into primary and secondary brain injury. Primary brain injury is the damage to brain parenchyma as a direct cause of trauma and secondary brain injury is the increased tissue damage that progresses after the primary insult and adds to the final lesion. Improved prognosis which can be observed as indicated by hospital length of stay, higher functional score, and reduction in mortality could be ascribed to the attenuation of secondary brain damage.[2,3]

Secondary brain damage mechanisms are disturbances of blood flow autoregulation, inflammation, free radical generation, excitotoxicity, and apoptosis. The apoptotic process follows two signaling pathways, a caspase-dependent pathway and a caspase-independent pathway, the latter has an intrinsic pathway mediated by mitochondrial failure and an extrinsic pathway mediated by death receptors. Induction of apoptosis by these two pathways activates the caspase cascade resulting in the activation of caspase-3 as executor caspase.[4,5]

Bcl-2 is a proto-oncogene protein with antiapoptotic properties. Bcl-2 has an important role in survival-signal pathways which inhibit apoptosis. Bcl-2 controls apoptotic intracellular signal transduction by preventing the out flux of cytochrome C from mitochondria through the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore preventing cytochrome c forming the apoptosome by binding caspase 9 and Apoptotic Protease Activating Factor-1. Thus, the increase of Bcl-2 would protect neurons from apoptotic death in the secondary brain damage phase.[6,7,8]

One of the neuroprotective agents in neuronal apoptosis is ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 or MEHFPGP. ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 is a synthetic peptide constituting a short fragment of ACTH, free of hormonal effects, with the potential to inhibit apoptosis by increasing Bcl-2. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 160 acute carotid ischemic stroke patients, ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 therapy showed a reduction of mortality as much as 76.6% in moderate and mild cases, and 77.3% in severe cases. The increase of Bcl-2 is compared with baseline on admission 20 times higher in CSF on day 3 and peaks on day 7 in serum.[9]

The goal of this study is to compare the effect of standard therapy with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10, the increase of Bcl-2 serum levels, and the reduction of hospital stay. The hypothesis is that standard treatment combined with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 would increase Bcl-2 levels and result in improved clinical outcome.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sampling

This is an experimental study and ethical clearance has been given by the Board of Ethics, Faculty of Medicine University of Sumatera Utara. Forty patients were taken into the study after consecutive sampling. The subjects were aged 18-60 years with MHI: Glasgow Coma Scale (9-12) with onset under 48 hours and with cerebral contusion as indicated by head CT scan without indication for surgery. Pregnancy, history of anticoagulants, malignancy cases, and epilepsy were exclusion criteria of this study.

The initial management for patients coming to the Emergency Unit followed Advanced Trauma Life Support principles. Then patients were given standard treatment corresponding to the Department of Neurosurgery University of Sumatera Utara's consensus. Patients were then divided into two groups by randomization. The first group was given standard therapy only. The second group was given standard therapy combined with intranasal application of ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 (Semax®) for 5 days using consecutive dosages of 9 mg/day, 6 mg/day, and 3 mg daily for the remaining 3 days.

Serum collection

Blood (6 cc) was drawn on day 1 and day 5 after trauma. The procedure utilized 20 G syringes (Terumo®) on the right medial cubital vein. The blood was transferred into centrifuge-capable tubes and stored at room temperature until coagulation was observed, then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min (Eppendorf 5702). The serum was collected and stored in cold storage at −20°C until all data sampling was completed and ready to be analyzed (Sanyo Biomedical Freezer MDF-U730 Upright Laboratory).

Bcl-2 assay

The serum Bcl-2 was quantitatively analyzed by Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay method, using Chemwell 2910 (Awareness Technology Inc.). The reagents used were Human Bcl-2 Recombinant Protein (H00000596-P01) from Abnova Corporation (Taiwan). The serum analysis was conducted at the Clinical Pathology Laboratory of RS. H Adam Malik (H Adam Malik Hospital).

Outcome

Clinical outcome was evaluated by Barthel Index (Maryland State Medical Society) and MMSE (Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.) on the day patients were discharged.

Statistical analysis

Category variables were analyzed by frequency and percentage and presented in tables or graphs. Numeric variables were descriptively analyzed in form of mean, median. and standard deviations. In the case of normal data spreads, paired means and standard deviations were used. If the data spreads deviated from normal, median with maximum–minimum were used.

For normality, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used with P < 0.05. Nonpaired data with normal spread were analyzed with nonpaired t-test. Nonpaired data with non-normal spread were analyzed with Mann–Whitney test.

The correlation in numeric data was analyzed with Pearson correlation test, for normal spread data, and Spearman test in non-normal spread data.

Results

MHI patients were found predominantly in males 18-29 years of age with initial GCS of 10.98 ± 1.43. Four patients were excluded from this study because of mortality in the first 3 days: Three patients in the standard group and one patient in the therapy group.

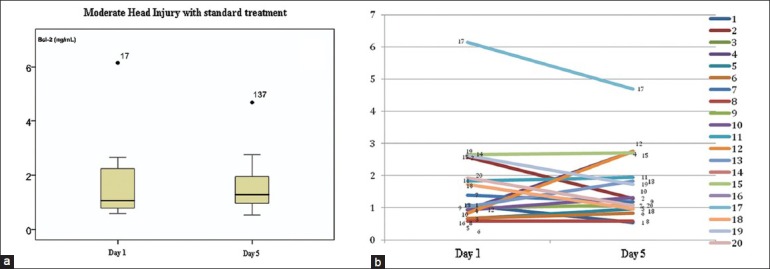

Bcl-2 changes with standard treatment

On Figure 1a the Bcl-2 mean of day 1 was 1.68 ± 1.34 ng/mL and at day 5 the mean was 1.66 ± 1.06 ng/mL. Mann–Whitney test was used because of non-normal data spread and the result showed insignificant differences (P > 0.05). Figure 1b showed the changes of Bcl-2 levels case by case. Nine samples showed an increase and the other eight samples showed a decrease. The subject with the highest decrease was the one with a high Bcl-2 level on day 1 as outlier (sample no. 17).

Figure 1.

The change in Bcl-2 in the group of MHI with standard treatment. (a) The mean spread and standard deviation with one outlier. (b) Bcl-2 change case by case

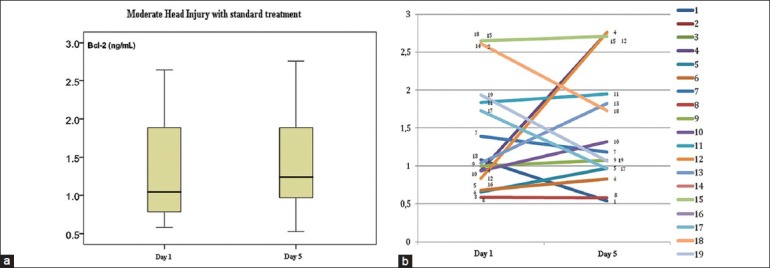

Figure 2 shows that Bcl-2 increased on day 5 (1.48 ± 0.77 ng/mL) compared with day 1's concentration (1.39 ± 0.75 ng/mL) after the outlier was ruled out. Because the distribution of data was normal, independent t-test was used. There was no significant difference in Bcl-2 concentration between day 1 and day 5. In the case by case graph after the outlier had been ruled out, nine samples showed increased Bcl-2 and seven samples showed decreased Bcl-2.

Figure 2.

The decrease of Bcl-2 in MHI with standard therapy group after outlier data have been ruled out. (a) Mean spread and standard deviation. (b) Bcl-2 change case by case

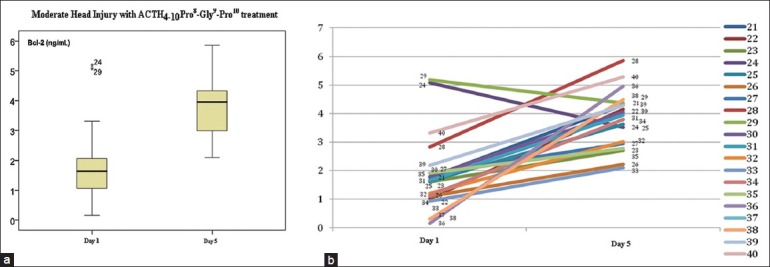

Bcl-2 Changes in standard treatment combined with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10

Figure 3 shows that mean serum Bcl-2 levels increased on day 5 (3.81 ± 1.00 ng/mL) compared with day 1 (1.93 ± 1.35 ng/mL). Based on independent t-test, the result was significant (P < 0.05). Case by case examination showed that in 17 samples Bcl-2 was increased and 2 samples showed a decrease in Bcl-2. The latter were outliers.

Figure 3.

The decrease of Bcl-2 in MHI in standard therapy combined with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group. (a) The mean spread and standard deviation. There were two outliers, which were sample no. 24 and sample no. 29. (b) Bcl-2 decreased in each case

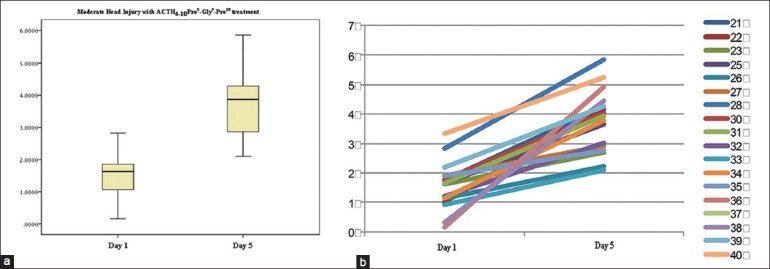

Figure 4, after the outlier had been ruled out, shows that serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 5 (3.70 ± 1.02 ng/mL) were higher compared with day 1 (1.39 ± 0.70 ng/mL). Based on independent t-test, there was a significant difference (P < 0.05). In the case by case graph, there were no sample subjects with a decrease in serum Bcl-2 concentration.

Figure 4.

The decrease of Bcl-2 in MHI in standard therapy combined with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group after the outlier had been ruled out. (a) Means and standard deviation, (b) case by case graph

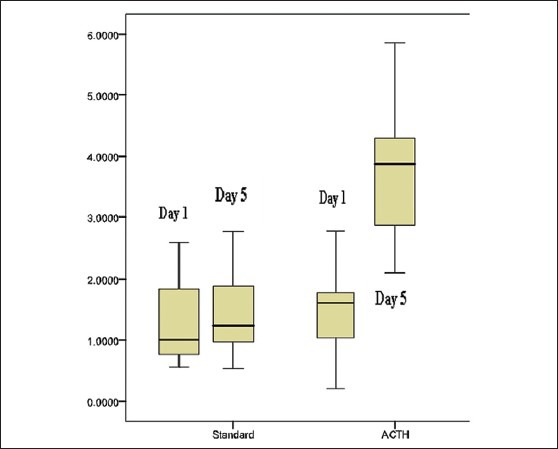

Intergroup difference of serum Bcl-2

Figure 5 On day 1, it was shown that the mean difference of Bcl-2 between the two groups was not significant (P > 0.05) by independent t-test. On day 5, the serum Bcl-2 concentration was significantly increased. The serum Bcl-2 concentration in the group with standard therapy combined with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 is significantly higher compared with the standard treatment group (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Intergroup serum Bcl-2 concentration

Comparison of length of stay

Correlation of Bcl-2 concentration on day 1 and day 5 with outcome

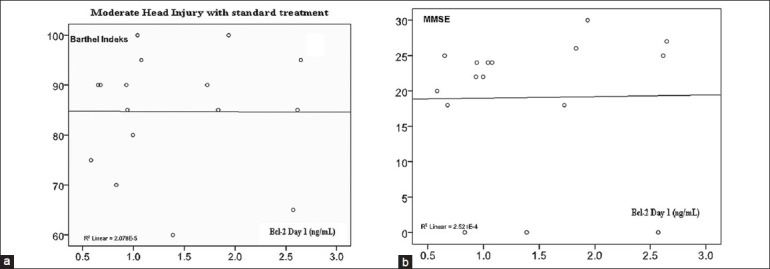

On Figure 6, there was no significant correlation between Bcl-2 day 1 with Barthel Index and MMSE in standard therapy group.

Figure 6.

(a) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration with Barthel Index (r = −0.005; P = 0.493). (b) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration with MMSE (r = 0.016; P = 0.477)

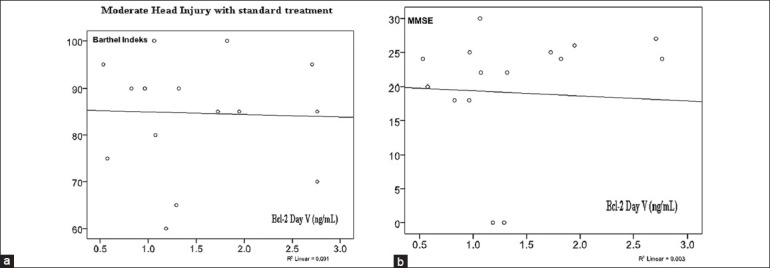

On Figure 7, there was no significant correlation between serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 5 with Barthel Index and MMSE in standard therapy group.

Figure 7.

(a) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 5 with Barthel Index (r = 0.034; P = 0.450). (b) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration with MMSE (r = 0.057; P = 0.418)

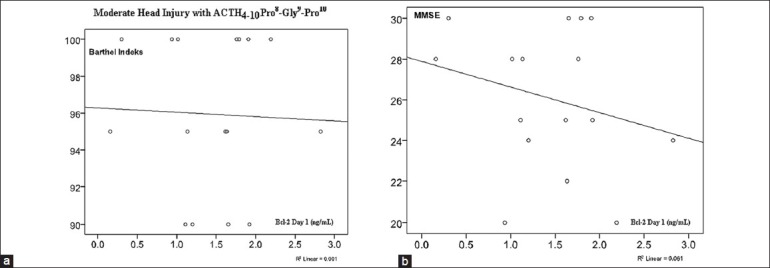

On Figure 8, there was no significant correlation between serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 1 with Barthel Index and MMSE in the ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group.

Figure 8.

(a) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 1 with Barthel Index (r = 0.515; P = 0.025). (b) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration with MMSE (r = 0.036; P = 0.449) there were no significant correlation

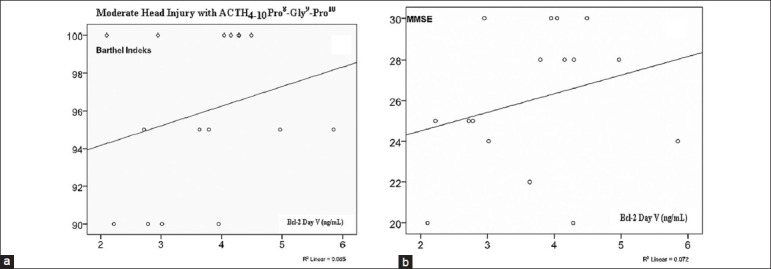

On Figure 9, there was no significant correlation between serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 5 with Barthel Index and MMSE in the ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group.

Figure 9.

(a) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 5 with Barthel Index (r = 0.336; P = 0.111). (b) Correlation of serum Bcl-2 concentration with MMSE (r = 0.015; P = 0.479) there were no significant correlation

Discussion

From this study, the age group that have highest incidence of head injury is the 18-29 years age group with a predominance of males. In the United States and Europe, incidence of head injury is highest at 15-24 years of age with male predominance.[10,11]

In the standard therapy group, the increase of serum Bcl-2 was not significant, 1.39 ± 0.75 ng/mL on day 1 to 1.48 ± 0.77 ng/mL on day 5.

There was a significant increase in serum Bcl-2 concentration in the ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group, 1.93 ± 1.35 ng/mL on day 1 to 3.81 ± 1.00 ng/mL on day 5 [Figure 4]. Gusev dan Skvortsova (2003) in their study with ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 administered to a population of 160 carotid ischemic stroke patients with dosages of 6 mg/day, 12 mg/day, and 18 mg/day found a significant increase of serum Bcl-2. The serum Bcl-2 concentration kept increasing with dosage increments as high as 18 mg/day.[9]

The length of stay on ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group was significantly shorter compared with the standard therapy group. Gusev dan Skvortsova (2003) used ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 on ischemic stroke patients and found that there was a shorter hospital length of stay compared with the standard group.

In this study, some outliers were found in serum Bcl-2 concentration measurement data, which deviated from standard deviation. The outliers might be caused by polymorphism of the Bcl-2 gene. In one study, there was a correlation between genotype Bcl-2 with global function after head injury. From that finding it was known that there are allele variants for rs17759659 and rs1801018 with worse outcome [Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) and Disability Rating Scale (DRS)], higher mortality rate, and lesser Neurobehavioral Rating Scale-Revised (NRS-R). In contradiction to that finding, homozygote allele wild type for rs7236090 and homozygote variants from rs949037 correlates with better outcome (GOS and DRS). These results supported the chance of, genetic polymorphism especially genetic variance in Bcl-2 gene for prosurvival proteins which could affect the outcome of head injury.[12]

There is no significance in correlation between serum Bcl-2 concentration, either on day 1 or day 5, with Barthel Index and MMSE in this study. Although in ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group there was a positive correlation trend in serum Bcl-2 levels on day 5 when compared with serum Bcl-2 on day 1. That trend could not be found in the standard group. Wagnes (2011) found there was a significant increase in serum Bcl-2 concentration correlated with better outcome, evaluated with GOS at 6 and 12 months post-trauma.[13] In this study, the reduced significance in correlation might be caused by clinical evaluation at the time of patient discharge and also by the small sample size in each group.

Conclusion

Significant increase of serum Bcl-2 levels and decrease of hospital length of stay were found in the ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group compared with standard therapy alone. There was a trend toward positive correlation between serum Bcl-2 concentration on day 5 with Barthel Index and MMSE on ACTH4-10Pro8-Gly9-Pro10 group.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rutland-Brown W, Langlois JA, Thomas KE, Xi YL. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:544–8. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stahel PF, Shohami E, Younis FM, Kariya K, Otto VI, Lenzlinger PM, et al. Experimental closed head injury: Analysis of neurological outcome, blood brain barrier dysfunction, intracranial neutrophil infiltration and neuronal cell death in mice deficient in gene for inflammatory cytokines. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:369–80. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis G, Marion D, George B, Hamel O, Turner M, McCrory P. Clinics in neurology and neurosurgery of sport: Traumatic cerebral contusion. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:451–4. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baliga B, Kumar S. Apaf-1/cytochrome c apoptosome: An essential initiator of caspase activation or just a sideshow? Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:16–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hague A, Paraskeva C. Apoptosis and disease: A matter of cell fate. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:1366–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim R. Unknotting the roles of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:336–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomenius MJ, Distelhorst CW. Bcl-2 on the endoplasmic reticulum: Protecting the mitochondria from a distance. J cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 22):4493–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng X, Gao F, Flagg T, Anderson J, May WS. Bcl-2's flexible loop domain regulates p53 binding and survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4421–34. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01647-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gusev EI, Skvortsova VI. Neuroprotection in brain ischemia. In: Gusev RI, editor. Brain Ischemia. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 237–322. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruns J, Jr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: A review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(suppl 10):2–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraus JF, McArthur DL. Epidemiology aspects of brain injury. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:435–50. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoh NZ, Wagner AK, Alexander SA, Clark RB, Beers SR, Okonkwo DO, et al. BCL2 Genotypes: Functional dan neurobehavioral outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1413–27. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner AK, McCullough EH, Niyonkuru C, Ozawa H, Loucks TL, Dobos JA, et al. Acute serum hormone levels: Characterization and prognosis after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:871–88. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]