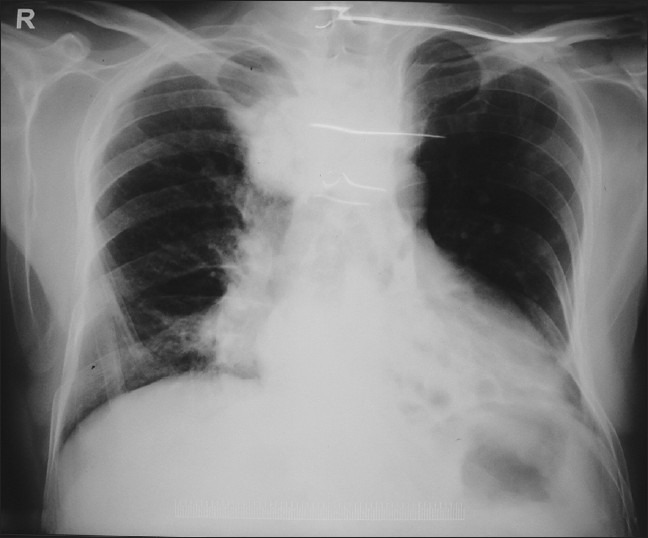

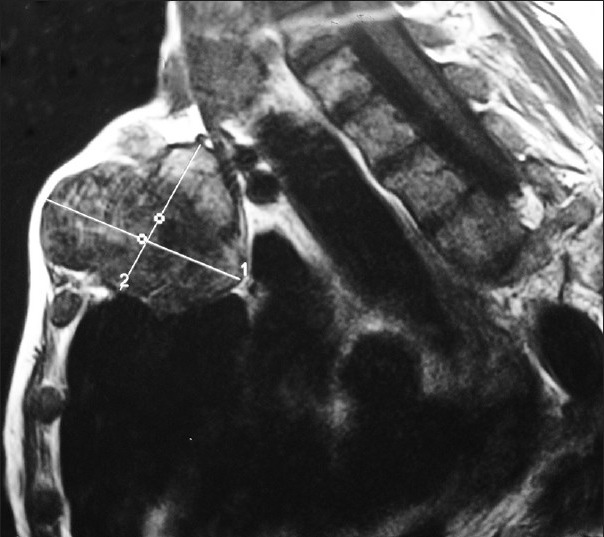

A 57-year-old male presented with complaints of chest pain for 8 months and swelling in upper anterior chest wall for 2 months, which were gradually increasing. He had no history of fever, chest trauma, weight loss, cough, or dyspnoea. His medical and surgical history for past illnesses was unremarkable. On local examination, a big potato-like swelling attached to the sternum [Figure 1] with slightly raised temperature and irregular margins was observed. The consistency of the swelling was hard and it was freely mobile. Rest of the respiratory system examination was normal. Examination of the cardiovascular system, central nervous system, abdomen, musculo-skeletal and reticulo-endothelial systems revealed no abnormality. His hemogram, liver function tests and kidney function tests were within normal range. Profiles for all collagen vascular diseases were negative, and random blood sugar was 132 mg/dl. Chest radiograph revealed mediastinal widening [Figure 2] and bronchiectatic changes in the left lower lobe, computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest [Figure 3] showed a large potato-like mass behind manubrium and upper body of sternum with extensive irregular calcifications. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of sternum [Figure 4] revealed a large retrosternal expansile destructive mass (size 5.2 cm × 7.8 cm × 6 cm, h, w, d) which was extending to anterior mediastinum and up to the carina, abutting and possibly adherent to a small segment of right brachiocephalic vein just distal to its junction with superior vena cava. The remaining mediastinal vessels including the aortic arch, left innominate vein, and the superior vena cava were free.

Figure 1.

Potato-like swelling over the chest

Figure 2.

X-ray chest showing mediastinal widening

Figure 3.

CT chest showing extensive calcifications

Figure 4.

MRI sternum

QUESTION

Q1. What is the diagnosis?

ANSWER

A hard swelling over the chest, X-ray chest showing a mediastinal widening and imaging studies revealing a large expansile destructive mass with extensive irregular calcifications are suggestive of malignancies. Most common diagnosis in this situation would be chondrosarcoma or osteosarcoma. Other conditions which can be considered are osteomyelitis, followed by inflammatory arthropathies like rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Disorder like pectus carinatum can also mimic this condition. The sternum as a whole is displaced anteriorly in pectus carinatum. This anomaly, also known as pigeon breast, occurs in approximately one per 1500 live births, more commonly in males than in females (M:F ratio 4:1). More than 30% cases of pectus carinatum are associated with scoliosis, and a small percentage are associated with congenital heart disease,[1] which was not the case in our patient. Familial occurrence is reported in approximately 25% patients. Clinical manifestations are not so frequent and include shortness of breath and exercise intolerance,[2] but there is no chest pain. The presentation of septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joints is acute or sub-acute, it is an uncommon infectious condition, which is usually monoarticular and insidious in onset. It manifests clinically as shoulder discomfort, low-grade fever, erythema, warmth, and swelling of the sternoclavicular joint. Concomitant sternal osteomyelitis occurs in 50% of cases, and abscesses are formed in about 20% of patients. Other complications include mediastinitis, superior vena cava syndrome, and septic shock. Risk factors include intravenous drug use, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis.[3,4] Our patient was not having much of local symptoms, he was hemodynamically stable and his blood sugar and Rh factor were normal.

Usually, such a large bony swelling is not seen in inflammatory conditions but more commonly point towards a neoplastic condition. Chondrosarcomas are more common, usually occur at more than 50 years of age with predilection of calcification at the peripheries; whereas ostesarcomas are rare, usually occur in less than 20 years of age group with predilection of calcification at the center.[5] Clinically, chondrosarcomas are painless while osteosarcomas are painful.[6] Radiologically, sternal osteosarcoma appears as a mass lesion that consists of bone and soft tissue and contains areas of osteolysis, calcification, and osteoid matrix.[7,8] A CT scan of the primary tumor is best for defining bone destruction and the pattern of calcification, whereas MRI is better for defining intramedullary, extra-osseous and soft tissue extension and invasion of the tumor into the adjacent tissues.[9] In our patient, CT chest revealed a large mass behind the sternum with extensive irregular calcifications and MRI scan showed the spread of the lesion to anterior mediastinum and up to the carina which was possibly adherent to a small segment of right brachiocephalic vein. Osteosarcomas have centrally dense widespread calcifications while chondrosarcomas tend to have flocculent or stippled calcifications.[8] Ringlike or arclike calcifications also have been described in chondrosarcomas. Almost 50% of the sternal malignancies are chondrosarcomas, while 20% are caused by osteosarcomas.[10]

FNAC and a trucut biopsy clinched the final diagnosis of primary osteosarcoma of the sternum. Further MRI studies showed secondaries in the spine (L1, L3 and L4 vertebrae) and iliac bone and bone scan revealed active bony lesion at L5. He was planned for and administered IAP-based palliative chemotherapy (Ifosphamide, Adriamycin and Cisplatin) as per his body surface area, but the patient could not make it and expired after 5 months.

Sarcomas are mesodermal neoplasms and are rare (< 1% of all malignancies) that arise in bone and soft tissues, and the bony sarcomas are still rarer accounting for only 0.2% of all new malignancies.[9] Osteosarcomas are malignant mesenchymal neoplasms that rarely occur in the thorax.[8] The rib, scapula, and clavicle are the most frequent sites of origin. Lesions originating in these osseous sites usually manifest in young adults. The overall survival rate among patients with thoracic osteosarcomas is approximately 15%, much lower than that among patients with limb osteosarcomas (60-70%).[7]

The case is being presented as it is extremely rare.[9] This patient was unique as osteosarcoma of the sternum is less common than that of extremities, occurred at a later age, had extensive irregular calcifications and had a very pictorial presentation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shamberger RC. Congenital chest wall deformities. In: O’Neill JA Jr, Rowe MI, Grosfeld JL, Fonkalsrud EW, Coran AG, editors. Pediatric surgery. 5th ed. St. Louis Mo: Mosby; 1998. pp. 787–817. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonkalsrud EW, Beanes S. Surgical management of pectus carinatum: 30 years’ experience. World J Surg. 2001;25:898–903. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein MA, Spreitzer AM, Miro PA, Carrera GF. MR imaging of the abnormal sternoclavicular joint: A pictorial essay. Clin Imaging. 1997;21:138–43. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(96)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-Natan M, Salai M, Sidi Y, Gur H. Sternoclavicular infectious arthritis in previously healthy adults. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:189–95. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nam SJ, Kim S, Lim BJ, Yoon CS, Kim TH, Suh JS, et al. Imaging of primary chest wall tumors with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2011;31:749–70. doi: 10.1148/rg.313105509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoki J, Moser RP, Jr, Kransdorf MJ. Chondrosarcoma of the sternum: CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:806–10. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladish GW, Sabloff BM, Munden RF, Truong MT, Erasmus JJ, Chasen MH. Primary thoracic sarcomas. Radiographics. 2002;22:621–37. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma17621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tateishi U, Gladish GW, Kusumoto M, Hasegawa T, Yokoyama R, Tsuchiya R, et al. Chest wall tumors: Radiologic findings and pathologic correlation. II. Malignant tumors. Radiographics. 2003;23:1491–508. doi: 10.1148/rg.236015527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel SR, Benjamin RS. Soft tissue and bone sarcomas and bone metastases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, et al., editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 17th ed. Chapter 94. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2008. pp. 610–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downey RJ, Huvos AG, Martini N. Primary and secondary malignancies of the sternum. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;11:293–6. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(99)70071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]