Abstract

Background:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the quality of life of Neyshabur health-care staff and some factors associated with it with use of WHOQOL-BREF scale.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 522 staff of Neyshabur health-care centers from May to July 2011. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was applied to examine the internal consistency of WHOQOL-BREF scale; Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine the level of agreement between different domains of WHOQOL-BREF. Paired t-test was used to compare difference between score means of different domains. T-independent test was performed for group analysis and Multiple Linear Regression was used to control confounding effects.

Results:

In this study, a good internal consistency (α = 0.925) for WHOQOL-BREF and its four domains was observed. The highest and the lowest mean scores of WHOQOL-BREF domains was found for physical health domain (Mean = 15.26) and environmental health domain (Mean = 13.09) respectively. Backward multiple linear regression revealed that existence chronic disease in staff was significantly associated with four domains of WHOQOL-BREF, education years was associated with two domains (Psychological and Environmental) and sex was associated with psychological domain (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

The findings from this study confirm that the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire is a reliable instrument to measure quality of life in health-care staff. From the data, it appears that Neyshabur health-care staff has WHOQOL-BREF scores that might be considered to indicate a relatively moderate quality of life.

Keywords: Health-care staff, neyshabur, quality of life, WHOQOL-BREF

INTRODUCTION

In recent years there has been a broadening in focus in the measurement of health beyond traditional health indicators such as mortality and morbidity, and quality of life (QOL) has turned into an important outcome in clinical and interventional studies.[1] Different definitions of QOL have been proposed by different researchers or Organizations. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined “QOL” as “an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”.[2] Recently, many general instruments have been used to measure QOL in different groups (e.g., patients, workers, population and so on). One of these instruments is the World Health Organization QOL-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire which captures many subjective aspects of QOL.[3,4,5] This questionnaire is one of the best known instruments that has been developed for cross-cultural comparisons of QOL and is available in many languages.[6] This instrument, by focusing on individuals’ own views of their well-being, provides a new perspective on life. The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire has translated into Persian and then validated in Iran by Dr. Nedjat and co-workers.[7] Most studies were performed to evaluate quality of life in patients’ people,[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] but there are few studies that evaluated quality of life of health-care staff, which provide services for patients. Health-care staff provides higher quality services for their customers when they are healthy and have good quality of life. The objective of this study was to evaluate the quality of life of Neyshabur health-care staff and some factors associated with it with use of WHOQOL-BREF scale.

METHODS

This was designed as a cross-sectional study. The data were collected between May and July 2011, at the health centers in the city of Neyshabur (A city in Northeastern of Iran). Of all Neyshabur health-centers staff (n = 583), forty eight persons exclude from study because of disagreement of them. All participating subjects provided informed consent after being acquainted with the purpose of study.

Procedure and study instrument

In this study, questionnaires have been filled by participants and for enhance accuracy; all participants were informed that their responses would remain confidential. A trained person was present to explain how to complete the questionnaires. We used the brief version of the WHO's QOL scale (WHOQOL-BREF) in this study. This instrument derived from the WHOQOL-100. The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire contains two items from the Overall QOL and General Health and 24 items of satisfaction that divided into four domains: Physical health with 7 items (DOM1), psychological health with 6 items (DOM2), social relationships with 3 items (DOM3) and environmental health with 8 items (DOM4). Five hundred and thirty five of Neyshabur health-care staff filled out the Iranian version of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Each item of the WHOQOL-BREF is scored from 1 to 5 on a response scale. Raw domain scores for the WHOQOL were transformed to a 4-20 score according to guidelines.[6] Domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (i.e., higher scores denote higher QOL). The mean score of items within each domain is used to calculate the domain score. After computed the scores, they transformed linearly to a 0-100-scale.[35,36]

Dependent and independent variables

Four domains of WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire were considered as dependent variables. The other data collected were included sex, age, education years, marital status, employment type, income level (per month), job background, chronic disease existence and local residence as independent variables. The age of participants was represented by two categories of ≤35 year and >35 year. Education years was categorized into two groups: 0-12 year and >12 year. Marital status was categorized into two categories including single/divorced and married. Employment type was categorized into two categories including official and contractual. Income level was divided into two categories including ≤5 million rial and >5 million rial per month. Job background was divided into two categories including <10 year and year ≥10 year. chronic disease existence was categorized into two categories including yes and no. Local residence was categorized into two categories including urban and rural.

Statistical analyses

The information collected was organized with the SPSS software, version 16. Descriptive analyses performed including frequencies, percentages, ranges, means, and standard deviations (SD). Cronbach's alpha (internal consistency index) was used to estimate the reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF (Cronbach›s alpha values of 0.70 and over were deemed acceptable).[37] Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine the level of agreement between four domains of WHOQOL-BREF. Paired t-test was used to compare difference between score means of different domains of WHOQOL-BREF. To investigate the association between participants’ characteristics and their QOL, t-independent test was used. At the end Multiple Linear Regression (with backward method) was performed to control confounding effects. Transformed scores were used for statistical analyses in four domains. In this study, the level of significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

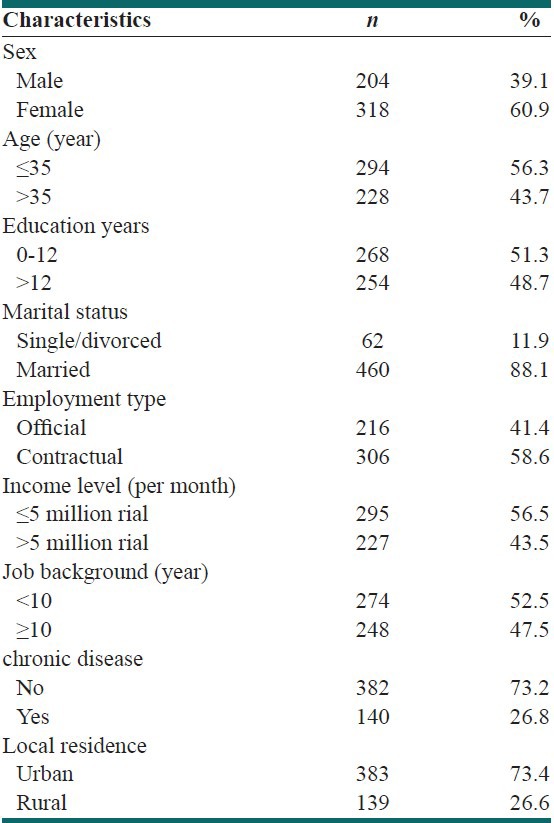

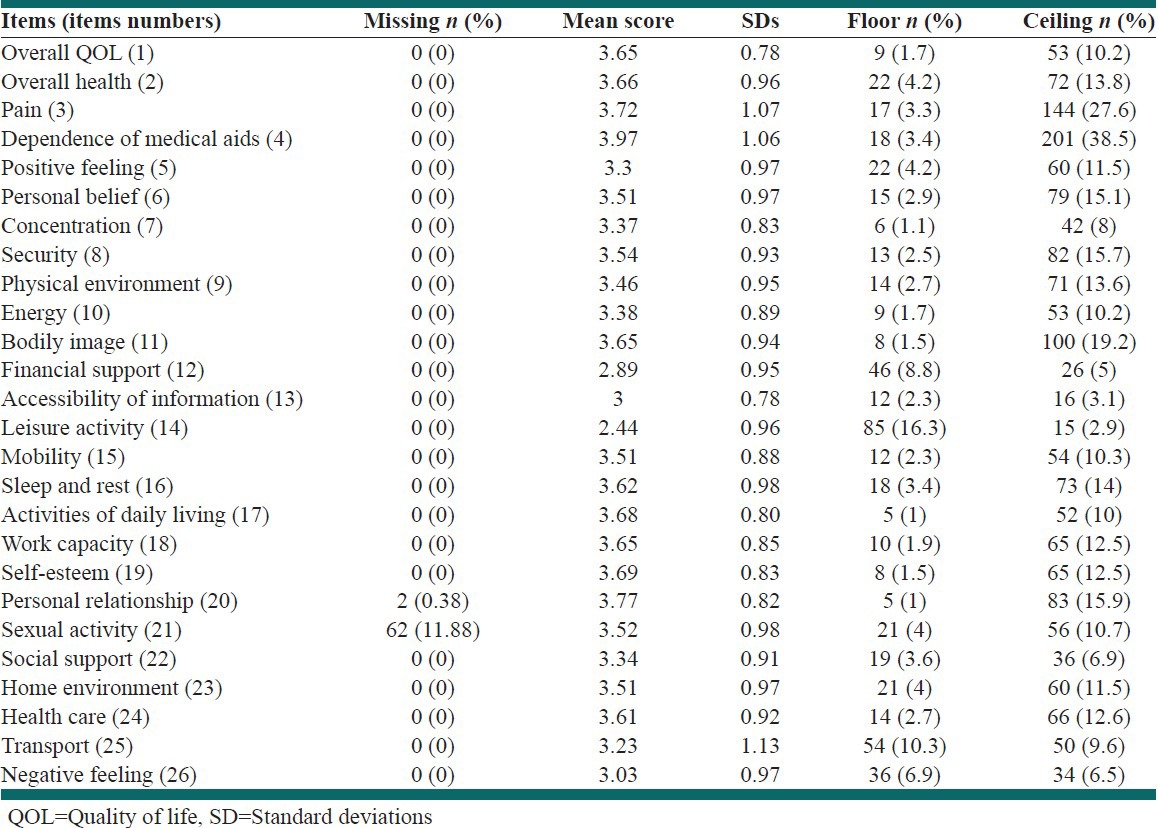

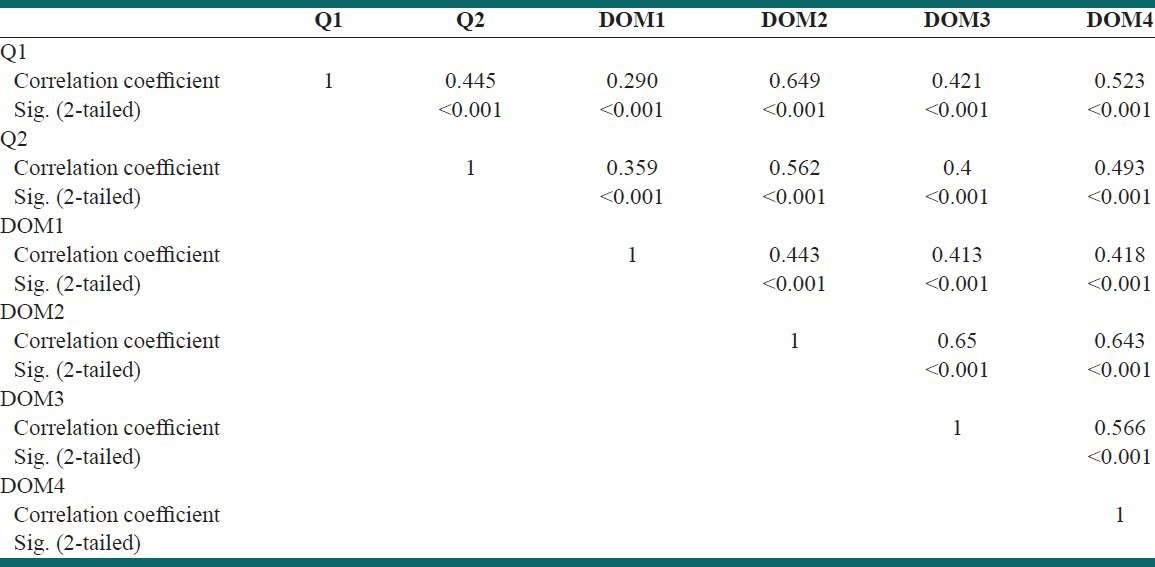

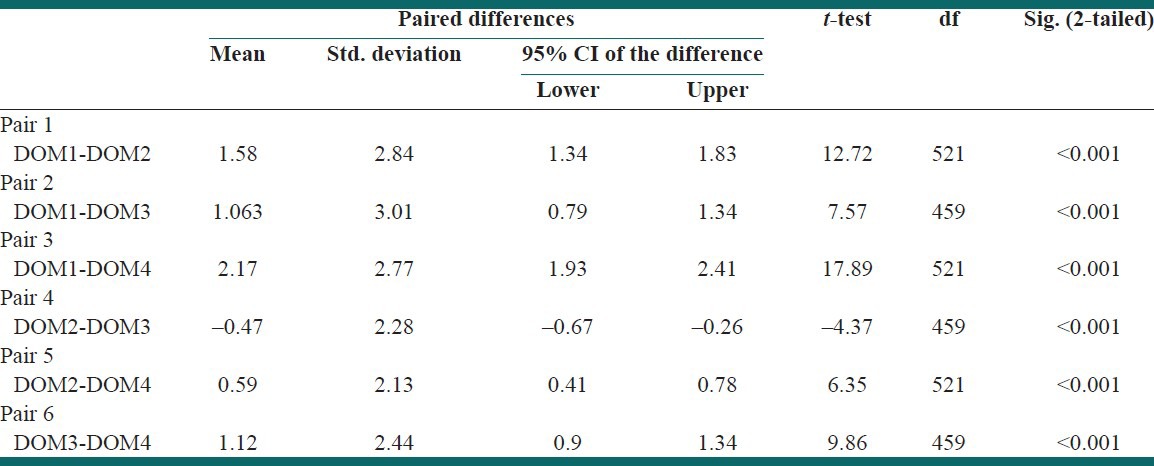

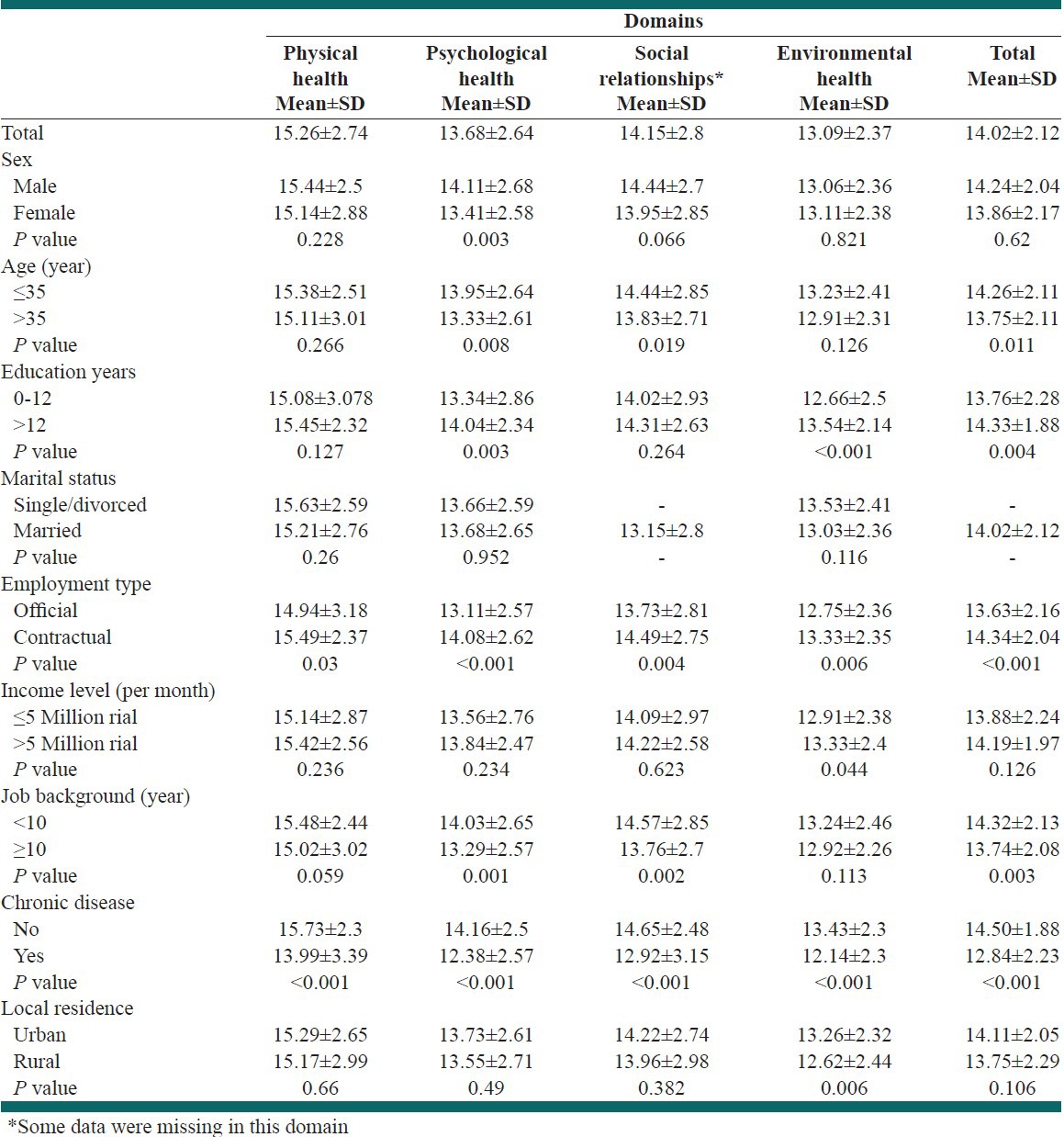

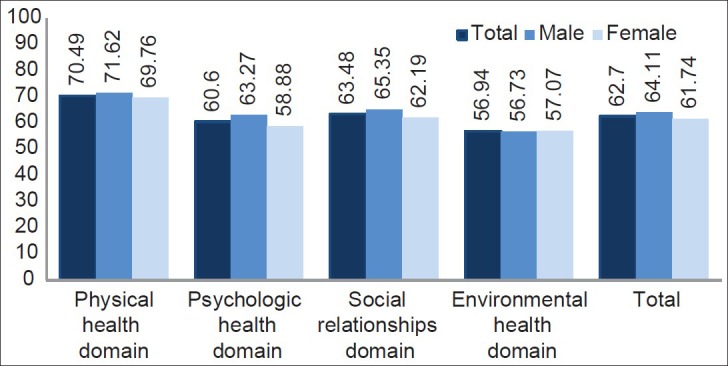

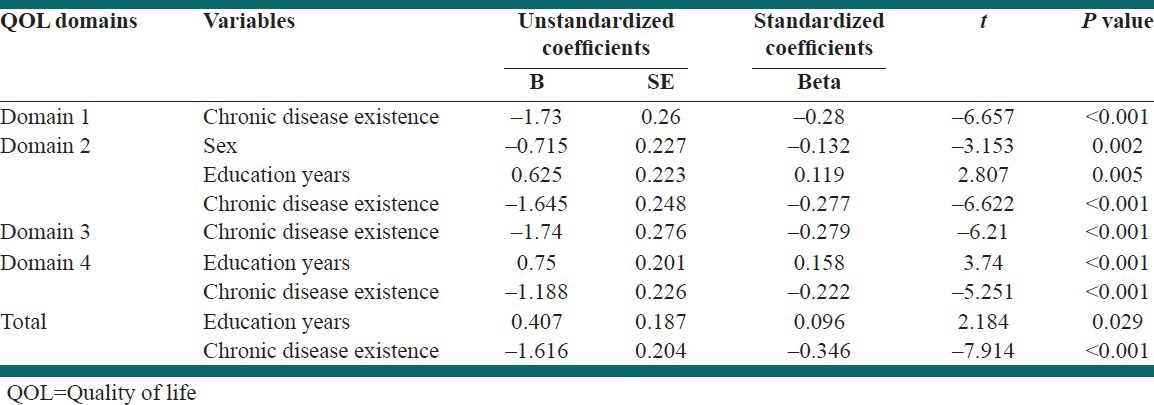

In total, 535 individuals filled out the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire in this study. Thirteen questionnaires had more than 20% missing data and thus were excluded from the study. The analysis was restricted for the remaining 522 respondents. The characteristics of study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of study population was 35.1 ± 7.7 year (Rang: 21-65 yr). Of all participants who completed WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire 318 persons (60.9%) were female, with a mean age of 33.38 ± 6.77 and 204 persons (39.1%) were male with a mean age of 37.76 ± 8.29. There was a significant difference between them in terms of age (P < 0.001). Table 2 depicts the missing, floor and ceiling effects for each item. The percentage of respondents scoring at the lowest level (floor effect) ranged from 1 to 16.3 while the percentage of respondents scoring at the highest level (ceiling effect) ranged from 2.9 to 38.5. In this study Cronbach's alpha coefficient was applied to examine the internal consistency of WHOQOL-BREF scale (26 items) as well as the four domains of it. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of WHOQOL-BREF was adequate (0.925) for all 26 questions and for each domain the values are: Physical health domain (0.813), Psychological health domain (0.811), Social relationship domain (0.65) and Environmental health domain (0.772). Table 3 present correlations between four domains of WHOQOL-BREF; as observed, there are statistically significant correlations between all domains. There is also statistically significant correlation between overall QOL (Q1) and scores obtained from different domains. In this study in order to compare the significant difference between score means of different domain ratings, the paired t-tests were used. As Table 4 shows, significant differences were found between all four different domains of WHOQOL-BREF. As seen in Table 5 and Figure 1, among the different domains, the highest and the lowest mean and percentage of satisfaction were found for DOM1 (Mean = 15.26; percentage = 70.49) and DOM4 (Mean = 13.09; percentage = 56.94) respectively. The mean score of four domains and total of WHOQOL-BREF according to sex, age, education years, marital status, employment type, income level, job background, chronic disease existence and local residence separately are presented in Table 5. Mean and percentage of satisfaction rating in DOM1, DOM2 and DOM3 was higher in males than females but this is reversed in the DOM4 [Table 5 and Figure 1]. As Table 5 shows, there were significant differences between different states of some variables in four domains and total of WHOQOL (P < 0.05). Table 6 illustrates the results of Backward Multiple Linear Regression, it is apparent that “existence chronic disease” and “education years” are significantly associated with total WHOQOL. “Existence chronic disease” is associated with four domains of WHOQOL, “education years” associated with DOM2 and DOM4, sex associated with DOM2. In the DOM1, the confounder was employment type; in the DOM2 and DOM3, age, employment type and job background were recognized as confounders and in DOM4, employment type, income level and local residence were confounders.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population (n=522)

Table 2.

Response pattern and missing items for each item (n=522)

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients in two overall questions and four domains of WHOQOL-BREF

Table 4.

Paired t-test for the four domains of WHOQOL-BREF

Table 5.

Comparison of the WHOQOL-BREF mean scores in four domains according to sex, age, education years, marital status, employment type, income level, job background, chronic disease existence and local residence

Figure 1.

Comparison transformed scores (0-100-scale) of the WHOQOL-BREF in four domains according to sex

Table 6.

Backward multiple linear regression analyses of significant factors associated with QOL

DISCUSSION

One of the major objective of this study was to evaluate the reliability (internal consistency) of WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire in health- care staff. Reliability analysis in this study indicated an acceptable internal consistency of WHOQOL-BREF scale (α = 0.925) and for each of its domains were high, except for social relationships domain that is partly low (α = 0.65) which is similar to Asnani (α=0.66), Skevington (α = 0.68) and Mazaheri (α = 0.62) studies.[38,39,40] Lower internal consistency can be attributed to the small number of questions (3 items) in social relationships domain. Other purpose of this study was to evaluate the QOL of Neyshabur health-care staff with use of the Iranian version of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies assessing QOL among the health-care centers staff in Iran.

QOL as a measurement can identify groups with physical or mental health problems and provide a guide to intervention and follow up evaluation.[41] In this study, among the four domains of WHOQOL-BREF, the highest mean satisfaction rating was found for DOM1 (physical health, Mean = 15.26), implying good activities of daily living, less dependence on medicinal substances and medical aids, enough energy and mobility, less pain and discomfort, sufficient sleep and rest and good work capacity. Moreover, the lowest mean score was shown for DOM4 (environmental support, Mean = 13.09), indicating not very good financial resources, opportunities for acquiring new information and skills and leisure activities. Most SD from mean (SD = 2.82) was observed in DOM3 (Social Relationships). Greater SD of mean obtained from DOM3 might be associated with different interpretations of the questions used in this domain and also small number of questions. As Table 4 shows, mean scores of four domains were different and statistically significant. The most difference was observed between DOM1 and DOM4. In Mazaheri’ study observed that mean scores of four domains were different and the most difference was between DOM1 and DOM4.[40] As seen in Table 5, the mean score of satisfaction rating in DOM1, DOM2 and DOM3 was higher in males than females but this difference was only statistically significant in DOM2 (Psychological Health). Some factors may be associated with lower psychological health in women as well as their job (e.g., pregnancy, delivery, milking, homemaking and so on) that need to do more investigation.

In this study, item 4 in responses had upper mean score (3.97) and item 14 had lower mean score (2.44). In Nedjat’ study observed that items 3 and 4 in responses had upper mean score and item 14 had lower mean score.[42] In this study after use of multiple linear regression (as shows in Table 6) observed that chronic disease existence is most important factor that affects QOL of study population in total and four domains of WHOQOL. Sex and education years were other factors that affect QOL of study population. In Abdollahpour’ study, the influential factors affecting each domain were: educational level and current disease in the physical health domain, employment status in the psychological health domain, status of house ownership and number of years employed in the environmental health domain and marital status in the social relationship domain.[43]

CONCLUSIONS

The findings from this study confirm that the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire is a reliable instrument to measure quality of life in health-care staff. From the data it appears that Neyshabur health-care staffs have WHOQOL-BREF scores that might be considered to indicate a relatively moderate quality of life. In this study observed that chronic disease in health-care staff is important health issue influencing quality of life of them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Neyshabur health-care staffs who willingly contribute in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was supported financially by Neyshabur Faculty of University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Fairclough DL. New York: Champan and Hall/CRC; 2002. Introduction in design and analysis of quality of life studies in clinical trials; p. 4.p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.What quality of life? The WHOQOL Group. World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment. World Health Forum. 1996;17:354–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHOQOL Group. Development of the WHOQOL: Rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23:24–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–85. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noerholm V, Groenvold M, Watt T, Bjorner JB, Rasmussen NA, Bech P. Quality of life in the Danish general population-normative data and validity of WHOQOL-BREF using Rasch and item response theory models. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:531–40. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018485.05372.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization's. Quality of Life group: WHOQOL-sBREF Introduction. Administration and Scoring. Field Trial version. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nedjat S, Montazeri A, Holakouie Naieni K, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh SR. The World Health Organization quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire: Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Iran J Health Sch. 2006;4:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danquah FV, Wasserman J, Meininger J, Bergstrom N. Quality of life measures for patients on hemodialysis: A review of psychometric properties. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37:255–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pizzo E, Pezzoli A, Stockbrugger R, Bracci E, Vagnoni E, Gullini S. Screenee perception and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer screening: A review. Value Health. 2011;14:152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soni RK, Porter AC, Lash JP, Unruh ML. Health-related quality of life in hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and coexistent chronic health conditions. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:e17–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taphoorn MJ, Sizoo EM, Bottomley A. Review on quality of life issues in patients with primary brain tumors. Oncologist. 2010;15:618–26. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter AC, Vijil JC, Jr, Unruh M, Lora C, Lash JP. Health-related quality of life in Hispanics with chronic kidney disease. Transl Res. 2010;155:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoniu SA. Effects of inhaled therapies on health-related quality of life in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:155–62. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimer T, Gerber B. Quality-of-life considerations in the treatment of early-stage breast cancer in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:791–800. doi: 10.2165/11584700-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers SN. Quality of life perspectives in patients with oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:445–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Bordeleau LJ, Lauzier S, Théberge V. Quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer: An updated systematic review (2001-2009) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:178–231. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan SY, Eiser C, Ho MC. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review. (e1-10).Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:559–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opara JA, Jaracz K, Brola W. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Med Life. 2010;3:352–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW ADT Survivorship Working Group. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: Recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2996–3010. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Batran SE, Ajani JA. Impact of chemotherapy on quality of life in patients with metastatic esophagogastric cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:2511–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Quality of life among long-term (≥5 years) colorectal cancer survivors-systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2879–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers A, Routledge T, Pilling J, Scarci M. In elderly patients with lung cancer is resection justified in terms of morbidity, mortality and residual quality of life? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:1015–21. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.233189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Razzolini L, Amato MP. Coping strategies, cognitive impairment, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:s227–30. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luckett T, King M, Butow P, Friedlander M, Paris T. Assessing health-related quality of life in gynecologic oncology: A systematic review of questionnaires and their ability to detect clinically important differences and change. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:664–84. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181dad379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller DM, Allen R. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: determinants, measurement, and use in clinical practice. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chase DM, Watanabe T, Monk BJ. Assessment and significance of quality of life in women with gynecologic cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1279–87. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor RM, Wray J, Gibson F. Measuring quality of life in children and young people after transplantation: Methodological considerations. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:445–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman AC, Simonton S. Advances in quality of life research among head and neck cancer patients. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:208–15. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landreneau K, Lee K, Landreneau MD. Quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis and renal transplantation-a meta-analytic review. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh J, Trabulsi EJ, Gomella LG. The quality-of-life impact of prostate cancer treatments. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:139–46. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown EA. Can quality of life be improved for the increasing numbers of older patients with end-stage kidney disease? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:661–6. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiqui F, Konski AA, Movsas B. Quality-of-life concerns in lung cancer patients. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:667–76. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JJ. Parkinson's disease: Health-related quality of life, economic cost, and implications of early treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(Suppl Implications):s87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CM, Cano SJ, Klassen AF, King T, McCarthy C, Cordeiro PG, et al. Measuring quality of life in oncologic breast surgery: A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures. Breast J. 2010;16:587–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skevington SM, Tucker C. Designing response scales for cross-cultural use in health care: Data from the development of the UK WHOQOL. Br J Med Psychol. 1999;72:51–61. doi: 10.1348/000711299159817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harper A, Power M. WHOQOL User manual. Edinburgh. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach's alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asnani MR, Lipps GE, Reid ME. Utility of WHOQOL-BREF in measuring quality of life in sickle cell disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazaheri M. Overall, and Specific Life Satisfaction Domains: Preliminary Iranian Students Norms. Irnian J Publ Health. 2010;39:89–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daher AM, Ibrahim HS, Daher TM, Anbori AK. Health related quality of life among Iraqi immigrants settled in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nedjat S, Montazeri A, Holakouie K, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R. Psychometric properties of the Iranian interview-administered version of the World Health Organization's Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): A population-based study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdollahpour I, Salimi Y, Nedjat SN, Jorjoran shushtari Z. Quality of life and effective factors on it among governmental staff in boukan city. Urmia J Med sci. 2011;22:40–7. [Google Scholar]