Abstract

The interaction of Cu(II) and Zn(II) ions with Amyloid-β (Aβ) plays an important role in the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. We describe the use of electron spin resonance (ESR) to measure metal binding competition between Cu(II) and Zn(II) in Amyloid-β at physiological pH. Continuous wave (CW) ESR show that Cu(II) has a significantly higher affinity towards Aβ(1–16) than Zn(II) at physiological pH. Importantly, of the two known Cu(II) coordination modes in Aβ, component I and component II, Zn(II) displaces Cu(II) only from component I. Our results indicate that at excess amounts of Zn(II) component II becomes the most dominant coordination mode. This observation is important as Aβ aggregates in the brain contain a high Zn(II) ion concentration. In order to determine details of the metal ion competition, ESEEM experiments were carried out on Aβ variants that were systematically 15N labeled. In the presence of Zn(II), most peptides use His 14 as an equatorial ligand to bind Cu(II) ions. Interestingly, Zn(II) ions completely substitute Cu(II) ions that are simultaneously coordinated to His6 and His13. Furthermore, in the presence of Zn(II), the proportion of Cu(II) ions that are simultaneously coordinated to His 13 and His 14 is increased. Based on our results we suggest that His 13 plays a critical role in modulating the morphology of Aβ aggregates.

Keywords: ESR, ESEEM, HYSCORE, Alzheimer’s disease, Metal ion coordination

INTRODUCTION

Metal ion competition in biological systems is important for maintaining a proper ion balance, which in turn is critical for homeostasis.1 Copper and zinc ions play critical roles in many biological pathways, including respiration, cell signaling and electron transfer.2–4 In the central nervous system metal ion competition is critical as these metal ions are involved in a large variety of activities including the development and maintenance of enzymatic activities, neurotransmission etc.5 Ionic imbalance in the central nervous system can lead into several neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia.6–8

Herein we examine the metal binding competition in the Aβ peptide which is involved in the Alzheimer’s disease. Much research has been conducted to determine the role metal ions play in the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Interestingly, micro particle induced X-ray emission microscopy measurements have shown that amyloid aggregates in brain tissues show abnormally high levels of Cu(II) and Zn(II).9 Furthermore, these metal ions are co-localized within the Aβ deposits.9 Several coordination modes have been proposed for these metal ions in Aβ, on the basis of several spectroscopic techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), circular dichroism, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, electronspray-ionization mass spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy.10–13 Most of these investigations were focused on single metal ion coordination in Aβ. In this work, we utilize ESR in conjunction with isotopic labeling to establish the coordination environment of Cu(II) in the presence of Zn(II).

The higher concentration of these ions in amyloid plaques9 raises the possibility that these metal ions might be involved in the plaque formation. Aβ peptide undergoes metal induced oligomerization under physiological conditions.14 It is important to note that the aggregated states of Aβ-Cu(II) and Aβ-Zn(II) are very different. Saxena and co-workers reported that Cu(II) induces mature fibril formation at sub-equimolar concentrations, while granular amorphous aggregates are observed at higher concentrations of Cu(II).15 Zn(II) on the other hand forms more amorphous aggregates rather than fibrillar aggregates even at sub equimolar concentrations.16–17 It has been suggested that the different coordination modes of Cu(II) and Zn(II) ions in Aβ are related to the different morphologies and toxicities of aggregates.18–19

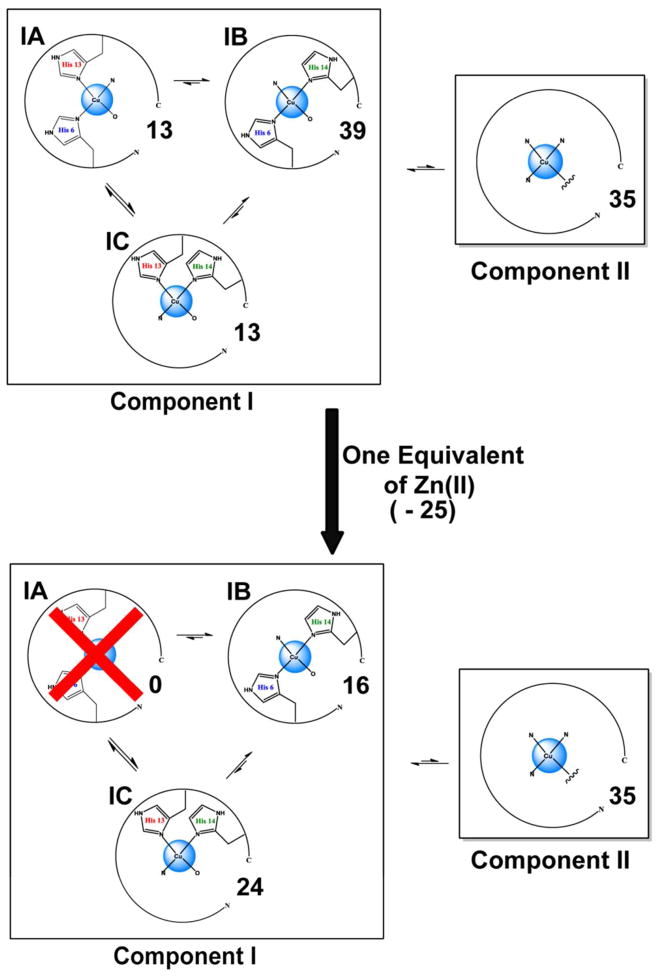

The Cu(II)-ion coordination in Aβ(1–16) has been shown to be identical to that in the full length Aβ.20–22 Continuous-wave electron spin resonance (CW-ESR) spectroscopy has revealed that there are two major coordination modes in Aβ-Cu(II), known as component I and II.23–25 Component I is the major Cu(II) coordination mode at physiological pH, accounting for 65% – 75% of the overall coordination.10, 26 A number of experimental techniques have revealed that the histidine residues in Aβ at positions 6, 13, and 14 are involved in the Cu(II) coordination.10, 12–13, 25 Previous work done in our group using electron spin echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) spectroscopy and hyperfine sublevel correlation (HYSCORE) showed that all three histidine residues in Aβ(1–16) are involved in the coordination of Cu(II).27 In component I, Cu(II) is thought to be coordinated to two out of three histidine residues present in Aβ at positions 6, 13 and 14. Depending on which histidine residues are coordinated to Cu(II) two possible coordination modes for Cu(II) component I were proposed at pH 6.0.24 Component IA contains simultaneous coordination of His 6 and 13, while component IB contains His 6 and 14 (cf. Figure 1). At pH 6.0, the simultaneous coordination of Cu(II) by His 13 and 14 is almost nonexistent. However, Shin et. al. showed that simultaneous coordination of His 13 and 14 is as important as His 6 and His 13 coordination at physiological pH.26 Thus a subcomponent IC, as shown in Figure 1, was introduced to account for the simultaneous His 13 and 14 coordination. A recent investigation done in Aβ(1–40) fibrils using pulsed ESR revealed a bis-cis-His equatorial coordination geometry for Cu(II).28 Also, this research proposed a structure where Cu(II) is coordinated to His 6/His 13 and His 6/His 14 alternatively along the fibrillar axis on the opposite sides of the β-sheet structure.28 The other two equatorial ligands for Cu(II) component I, are believed to be the N-terminus21, 24–25 and the carbonyl oxygen from Asp 1.24

Figure 1.

Three proposed subcomponents for component I in Cu(II) coordinated to Aβ peptide. In subcomponent IA, His 6 and 13 simultaneously coordinate the Cu(II) ion in the uatorial plane. Subcomponent IB Cu(II) coordinates His 6 and 14, while subcomponent IC coordination contains His 13 and 14

The metal binding site for Zn(II) ion lies in the N-terminal hydrophilic region of the Aβ(1–16) as is the case for Cu(II).29–30 It is believed that all three histidine residues are involved in the coordination of Zn(II) in Aβ(1–16).30–34 Classically Zn(II) coordination involves four to six ligands. The identities of other ligands are still controversial. The Aβ ligands proposed in binding Zn(II) in addition to the three histidine residues are the N-terminal amine from Asp 1, the Glu 11 carboxylate side chain, the deprotonated amide of the Arg 5 backbone and Tyr 10.10

The Cu(II) coordination in Aβ(1–16) is heterogeneous and involves all three histidine residues in different coordination modes. Given the coexistence of Cu(II) and Zn(II) in amyloid plaques, it is critical to study the Cu(II) coordination in the presence of Zn(II). This represents a better depiction of the in vivo environment. We used CW-ESR spectroscopy in conjunction with simulations to determine how Zn(II) competes with Cu(II) for Aβ(1–16) coordination at physiological pH. These results show that Cu(II) has an overall higher affinity towards Aβ(1–16) than Zn(II). Importantly, only component I of Cu(II) was substituted by Zn(II). Electron spin echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) experiments were carried out at low magnetic field (2800 G), at which only component I of Cu(II) coordination is present. Single labeled and double labeled peptides containing one and two 15N isotopically labeled histidine residues were used to obtain detailed information on the role of each histidine residue towards Cu(II) coordination. In the presence of equimolar amount of Zn(II) the ESEEM results suggest that approximately half of the peptides in the ensemble use His 14 as an equatorial ligand for Cu(II) coordination in component I. Furthermore, the proportion of subcomponent IC was increased in the presence of Zn(II). The atomic force microscopy (AFM) results obtained using Aβ(1–40) show that amorphous aggregates are prevalent in the presence of both Zn(II) and Cu(II).

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Peptide synthesis and Cu(II)/Zn(II) complex preparation

Isotopically enriched [G-15N]-Nα-Fmoc-Nτ-trityl-L-histidine, in which all nitrogen atoms are 15N enriched was purchased from Cambridge isotope Laboratory (Andover, MA). Three different variants of Amyloid-β(1–16) (DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK) containing an 15N enriched histidine at either position 6,13, or 14 were synthesized at the Molecular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh, using standard fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry.35–36 Double labeled peptides containing two 15N enriched histidine residues were synthesized in the same manner. All the labeled Amyloid-β(1–16) variants were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography and characterized by mass spectroscopy. Nonlabeled Amyloid-β (1–16) peptide was purchased from rPeptide (Bogart, GA). Isotopically enriched (98.6%) 63CuCl2 was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratory (Andover, MA), and anhydrous ZnCl2 powder (≥ 99.995 % metal basis) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). The enriched isotope was used to minimize inhomogeneous broadening of the Cu(II) ESR spectra. N-ethylmorpholine (NEM) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO).

2.5 mM solutions of peptides were prepared in 100mM NEM buffer (pKa = 7.8) at pH 7.4 in 50% (v/v) glycerol and appropriate amounts of hydrochloric acid. Cu(II) and Zn(II) stock solutions of 10 mM concentration were prepared in NEM buffer. Appropriate amounts of stock solutions of Cu(II) and Zn(II) were added to a tube. Then the peptide was added to the tube containing Cu(II) and Zn(II) to make sure the peptide coordinates with both the metal ions simultaneously. The final peptide concentration of the ternary complexes was 1.25 mM. For all ESEEM experiments equivalent amounts of Cu(II) and Zn(II) were added(peptide: Cu(II): Zn(II) = 1:1:1). For CW experiments the metal ion concentrations were changed to provide the desired ratios. Samples of double isotopic labeled peptide were prepared following the same procedure used for the single isotopic labeled ones.

Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy

A 200 μL aliquot of the sample was transferred into a quartz tube with an inner diameter of 3 mm. Electron spin resonance experiments were performed either on a Bruker ElexSys E580 or a Bruker ElexSys E680 X-band FT/CW spectrometer equipped with Bruker ER4118X-MD5 and EN4118X-MD4 resonators, respectively. The temperature was controlled using an Oxford ITC503 temperature controller and an Oxford CF935 dynamic continuous flow cryostat connected to an Oxford LLT 650 low-loss transfer tube. All samples were frozen quickly by immersing in liquid nitrogen. Then, the samples were inserted into the sample cavity which was pre-cooled to the desired temperature (20 K or 80 K).

Continuous-wave ESR experiments were carried out on sample solutions at 80 K with a microwave frequency of approximately 9.69 GHz. The magnetic field was swept from 2600 to 3600 G for 1024 data points. A time constant of 40.96 ms, a conversion time of 81.92 ms, modulation amplitude of 4 G, a modulation frequency of 100 KHz, and a microwave power of 0.1993 mW were the other instrument parameters used for the CW experiment. The experimentally obtained spectra were compared with simulations using Bruker-Simfonia.

Three-pulse ESEEM experiments were performed on the sample solutions at 20 K, by using a π/2-τ-π/2- T-π/2-echo pulse sequence with a π/2 pulse width of 16 ns. The first pulse separation, τ, was set at 144 ns, and the second pulse separation, T, was varied from 288 ns with a step size of 16 ns with the magnetic field strength fixed at 2800 G. Component I of the Cu(II)-Aβ(1–16) complex is almost exclusively observed at this magnetic field at physiological pH. A four-step phase cycling was employed to eliminate unwanted echoes.37–38 The raw data were phase corrected and the real part was selected. After the baseline correction, the data were fast Fourier-transformed. Then the final spectra were obtained as the magnitude of the Fourier transforms.

Four-pulse HYSCORE experiments were carried out at 20 K with a pulse sequence of π/2-τ-π/2-t1-π-t2-π/2-τ-echo with π/2 and π pulse lengths of 16 and 32 ns respectively. The first pulse separation, τ, was set at 144 ns, and both the second (t1) and third (t2) pulse separations were varied with a step size of 16 ns and 100 shots per points. The final data consisted of 256 data points in both t1 and t2. The magnetic field was fixed at 3360 G where the echo intensity is a maximum. Four-step phase cycling was employed to eliminate unwanted signals. The real parts of the collected two-dimensional data were baseline corrected and zero filled to 1024 points in both dimensions. After performing the twodimensional Fourier transformation the final spectra were obtained as contour plots of the magnitude of the Fourier transforms.

ESEEM data analysis

For systems where Cu(II) is coordinated to 14N, the ESEEM spectrum contains three characteristic peaks between 0 and 2 MHz.39–43 When the exact cancellation condition is fulfilled, these three ESEEM frequencies correspond to ν0, ν−, and ν+ for the nuclear quadrupole interaction (NQI) transitions.

| [1] |

In the equations above e is the electron charge, q is the z-component of the electric field gradient across the nucleus, Q is the 14N nuclear quadrupole moment, η is the asymmetry parameter, and h is Planck’s constant.

Apart from these three NQI peaks there is a broad peak around 3.8 MHz, which is attributed to a double quantum transition (DQ) 39–43. The double quantum transition frequency is given by44

| [2] |

Where νDQ is the double quantum transition frequency, νI is the Larmor frequency of 14N, and A and B are the secular and the pseudo secular part of the hyperfine interaction respectively.

In this work we compare the ESEEM signals of wild type Aβ(1–16) with 15N labeled Aβ(1–16) peptides. Upon 15N substitution the modulation depths of the signals due to 14N nuclei will decrease in ESEEM. This decrease is because the single quantum transition of 15N nuclei does not substantially contribute to the ESEEM signal.43, 45–49 In our approach 14N ESEEM signal is normalized by the 1H ESEEM signal as the 1H ESEEM modulation depth is not affected by a replacement of 14N with 15N. The decrease in the relative modulation depth of the 14N nuclear transition frequency can be calculated by comparing the relative integrated intensity of the 15N labeled peptide with the non-labeled peptide. For a single 14N nuclei coupled to an electron spin system, this decrease in modulation depth is,26

| [3] |

Where, K is the modulation depth, and f is the fraction of 14N nucleus that has been replaced. Subscripts 14 and 1 denote the 14N spin and 1H spin, respectively. Subscripts α and β represent the α and β spin manifolds of the electron spin, respectively. Shin and Saxena showed that this normalized 14N modulation depth is a monotonic function of the fraction of 14N that is replaced with 15N.26 It is evident that the decrease in the relative modulation depth of the 14N nuclear transition frequency is greater than that in the fraction of 14N. If and are much smaller than 1, the factor converges to (1–f), which is the fraction of 14N. For example if the and values are approximately 0.15 eq [3] becomes,

| [4] |

In the case of a 33% replacement of 14N with 15N, the ratio F(m14N/015N) is approximately 0.63, which indicates that the relative modulation depth of the 14N transition frequency decreases by 37%, just 4% greater than the expected from the fraction of replacement.

However, it is difficult to obtain modulation depths as many components are overlaid in the ESEEM time domain curve. Shin and Saxena showed that the integrated intensity can be used to account for the decrease in the modulation depth upon 15N labeling, in the 14N ESEEM signal.26 In the frequency domain the 1H signal is well separated from the signal produced by 14N so it is possible to integrate each separately. The 14N ESEEM integrated intensity is obtained by integrating between 0–8 MHz, and for the1H ESEEM the integration is done between 10–14 MHz. Thus relative integrated intensities can be used to calculate the fraction of 14N nuclei coordinated to Cu(II). Detailed equations for multiple histidine coordination are provided in reference 22.

RESULTS

Zn(II) competes with Cu(II) for Aβ (1–16) coordination

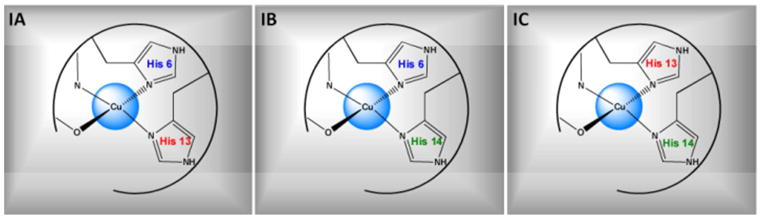

Continuous-wave ESR experiments were carried out on the equimolar mixture of Cu(II) and Aβ(1–16) in the presence and absence of Zn(II) in 100 mM NEM at pH 7.4 buffer. These experiments were performed to demonstrate the binding competition between Cu(II) and Zn(II) for Aβ(1–16)coordination. As Zn(II) is a diamagnetic ESR silent species, the change in the Cu(II) signal is used to investigate the effects of Zn(II) in the system. At the physiological pH in NEM buffer, free Cu(II) precipitates and does not contribute to the signal.23 Figure 2 shows the experimentally obtained CW-ESR spectra in the presence and absence of Zn(II). In the presence of one equivalent of Zn(II), the intensity of the ESR signal decreased as shown in Figure 2. Quantitatively the double integrated intensity was reduced by ~25 %. Upon the addition of four equivalents of Zn(II), the double integrated signal intensity of Cu(II) was decreased ~ 40 %. The decrease in the double integrated intensity of Cu(II) signal clearly illustrates the fact that Zn(II) competes with Cu(II) for Aβ(1–16) coordination. In order to understand how the Cu(II) signal intensity changes with the increase of Zn(II) concentration further CW experiments were carried out. The ratio of Aβ(1–16) and Cu(II) were kept constant and the Zn(II) ratio was changed from 0 to 10 in these experiments. The double integrated intensity of these CW spectra was calculated to elucidate the amount of Cu (II) bound to the peptide at different Zn(II) ratios (Figure S1). The amount of Cu(II) bound remains approximately constant after the addition of four equivalents of Zn(II) into the mixture. Approximately 60% of initially added Cu(II) is still bound to Aβ(1–16) even at large excess concentrations of Zn(II), under conditions where both metal ions compete simultaneously for peptide coordination.

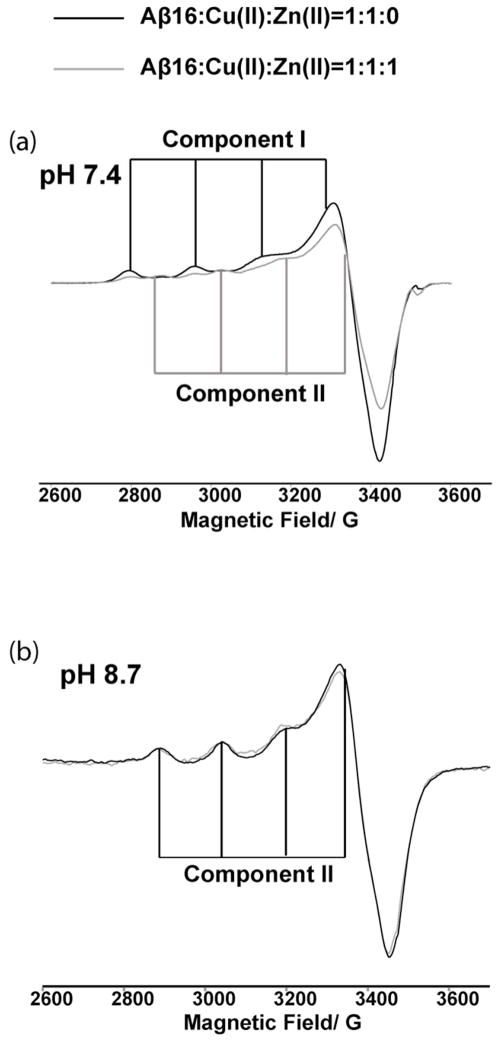

Figure 2.

CW-ESR spectra illustrating the reduction of Cu(II) intensity in the presence of Zn(II) when coordinated to Aβ(1–16) peptide at physiological pH. At equimolar amount, Zn(II) reduces the double integrated intensity of Cu(II) signal by ~ 25 % with respect to the no Zn(II) spectra, and at four equivalents of Zn(II) the signal intensity is reduced by ~ 40 %.

Zn(II) competes only with component I of Cu(II) at physiological pH

The Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) CW spectrum contains two clear components at physiological pH (cf. Figure 2). Component I, which is the major component for Cu(II) coordination at physiological pH, has g|| and A|| values of 2.26 ± 0.005 and 170 ± 1 G, respectively. These ESR parameters are consistent with a type II Cu(II) center, coordinated to three nitrogen ligands and one oxygen ligand in the equatorial plane 50. Likewise, the g|| and A|| values of 2.23 ± 0.005 and 156 ± 1G of component II is consistent with either three nitrogen ligands and one oxygen ligand or four nitrogen ligands coordination.50

A close inspection of CW-ESR spectra of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) and Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) showed an interesting pattern. Figure 3a shows the CW-ESR spectra of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) and Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) complexes at pH 7.4. Interestingly, in the presence of Zn(II) only the intensity of component I was decreased. The intensity of component II remains very similar in both the presence and absence of Zn(II). Spectral simulations were performed to quantify the proportion of each component in Aβ(1–16)- Cu(II) complex. ESR parameters used for the CW simulations are tabulated in Table S2. An overlay of experimental and simulation results are shown in Figure S2. In the absence of Zn(II) component I was the major component and accounts for ~65 % of the overall signal. However, in the Aβ(1–16)- Cu(II)/Zn(II) equimolar complex the amount of component I is ~50 %. At a fourfold excess of Zn(II) the proportion of component I is ~35 %. To confirm the selective substitution of Cu(II) by Zn(II), experiments were repeated at pH 8.7. At this pH only component II of Cu(II) binding is present. The double integrated intensity of Cu(II) signal in the presence and the absence of one equivalent of Zn(II) remained approximately the same as shown in Figure 3b, indicating Zn(II) was unable to displace Cu(II) from component II.

Figure 3.

(a) Overlay of CW-ESR spectra of Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) equimolar binary complex (black) and Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) equimolar ternary complex (grey) at pH 7.4 and (b) at pH 8.7. At pH 8.7 only the component II of Cu(II) binding is present. Interestingly double integrated intensity of the spectra remains almost the same, suggesting Zn(II) cannot compete with Cu(II) for component II coordination

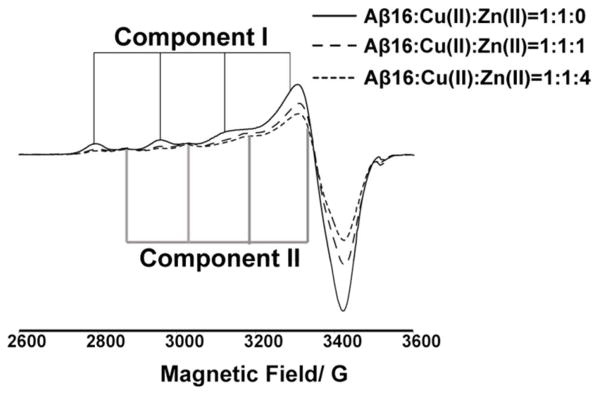

Contribution of each histidine residue for component I in Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) complex

As discussed earlier, all three histidine residues are involved in the Cu(II) coordination at physiological pH24–25, 27 and component I consists of three subcomponents as shown in Figure 1.26 Our CW results show that Zn(II) only competes with Cu(II) for component I coordination. Thus it is of interest to discover which subcomponents of component I compete with Zn(II) for Aβ(1–16) coordination by evaluating the contribution of each histidine residue to the Cu(II) coordination in component I. Experiments are carried out at magnetic field 2800 G, where the contribution from component II is negligible.

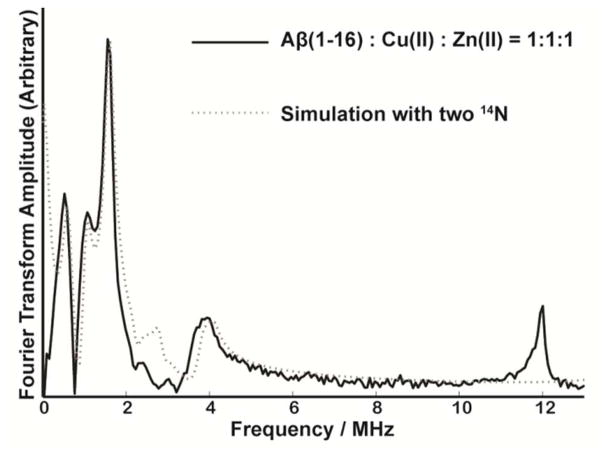

Figure 4 shows the ESEEM spectrum of unlabeled Aβ(1–16) peptide coordinated to Cu(II) and Zn(II) at physiological pH at 2800 G. The spectrum contains three peaks around 0.55, 1.01, and 1.54 MHz. The nuclear quadrupole parameters, e2qQ/h and η, are determined to be 1.70 ± 0.03 MHz and 0.65 ± 0.02, respectively. These numbers are comparable to those for Cu(II) histidine complexes.39–42 The broad peak around 3.8 MHz is due to a double quantum (DQ) transition of the remote nitrogen of the imidazole.51–52 As two histidine residues are likely simultaneously coordinate to Cu(II) on the equatorial plane, two simultaneous histidine coordination assumed to yield the best fit for ESEEM simulation (cf. Figure 4). Apart from the peaks arising from 14N, there is another peak around 11.9 MHz which is similar to the 1H Larmor frequency at 2800 G. This peak is a result of hydrogen atom(s) weakly interacting with the electron spin of Cu(II).

Figure 4.

Experimentally obtained and simulated three-pulse ESEEM spectra of the nonlabeled Aβ(1–16) peptide mixed with equimolar amounts of Cu(II) and Zn(II) at 2800 G at pH 7.4.

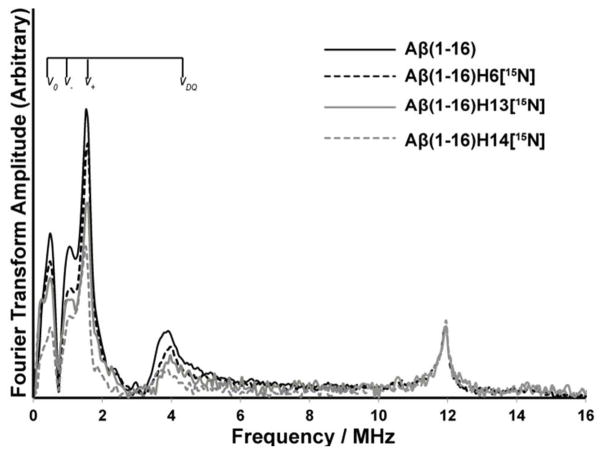

Next, we analyzed the three pulse ESEEM spectra obtained for three singly labeled Aβ(1–16) peptide variants. The spectra are shown in Figure 5. In these peptides a single histidine at either His 6, His 13 or His 14 is isotopically labeled with 15N. All these Aβ(1–16) variants were mixed with equivalent amounts of Cu(II) and Zn(II) at pH 7.4. The four spectra have similar line shapes and peak positions in the 14N ESEEM region. The similarity in the peak shapes implies that the ESEEM active 14N of each histidine residue has almost the same nuclear transition frequencies.42 In ESEEM experiments the 14N ESEEM intensity is related to the number of 14N histidine residues coordinated to Cu(II) (cf. Methods section). The Single-quantum transition of 15N, a nucleus with a spin of 1/2, contributes minimally (~ 2 %) towards the ESEEM signal.43, 48 Hence, when a 14N nucleus is replaced with a 15N the ESEEM signal intensity will decrease.

Figure 5.

Three-pulse ESEEM spectra of the nonlabeled and single 15N labeled Aβ(1–16) variants mixed with equimolar amounts of Cu(II) and Zn(II) at 2800 G at pH 7.4 (peptide: Cu(II): Zn(II) =1:1:1). The decrease in intensity below 8 MHz in 15N labeled Aβ(1–16) variants gives the contribution of each histidine residue for component I in Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) complex. Aβ(1–16)H6[15N], Aβ(1–16)H13[15N], Aβ(1–16)H14[15N] denote peptides where His 6, His 13, and His 14 are labeled with 15N, respectively.

The three pulse ESEEM spectra of three single labeled peptides and the wild type were normalized using their 1H ESEEM intensities at or around 11.9 MHz. Then the ESEEM spectra were integrated between 0 and 8 MHz and compared between the wild type and the 15N labeled peptides (cf. Methods section). As Figure 5 illustrates, the 15N labeled variants have lower intensities in the 14N region below 8 MHz. At physiological pH, the normalized 14N ESEEM intensity of His 14 labeled peptide decreased approximately 50% compared to the unlabeled ternary complex (cf. Aβ(1–16)H14[15N] in Figure 5). The decrease in 14N ESEEM intensity indicates that ~ 50% of the peptides in the ensemble use His 14 as an equatorial ligand in Cu(II) coordination. The reduction of 14N ESEEM intensity for His 6 and His 13 label samples were ~ 20% (cf. Aβ(1–16)H6[15N] in Figure 5) and 30% (cf. Aβ(1–16)H13[15N] in Figure 5), respectively. These values suggest that ~ 20% and ~ 30% of the peptides in the mixture equatorially coordinate to Cu(II) through His 6 and His13, respectively. Hence, His 14 becomes the most significant equatorially coordinated histidine ligand in Cu(II) binding (~ 50%) in component I. In the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) binary complex, both His 6 and His 14 were equally important in Cu(II) binding, accounting ~40% each.26 Thus, the Cu(II) coordination environment is rearranged in the presence of Zn (II).

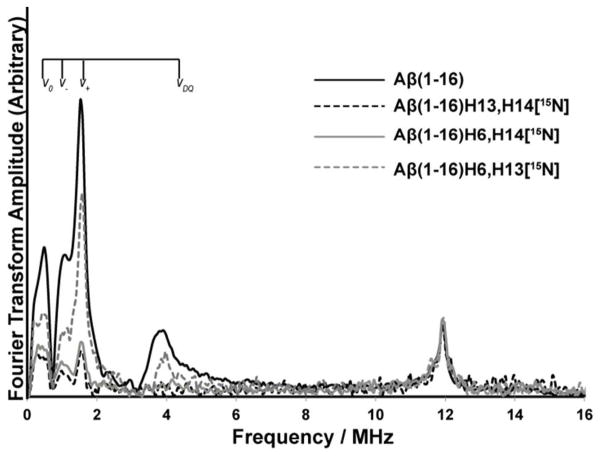

The same set of experiments was carried out using three doubly labeled Aβ(1–16) variants. In these double labeled peptides two histidine residues out of three in Aβ(1–16) are isotopically labeled with 15N. As two of the three histidine residues are labeled, 14N ESEEM signal intensity only results from the non-labeled histidine. This provides us a direct methodology to determine to what extent each of these residues is involved in the ternary complex. All the experiments were carried out at 2800 G, where only component I is present.

Despite low signal to noise, due to only one histidine giving the 14N ESEEM signal, with extensive signal averaging we were able to do the analysis. As shown in Figure 6, as expected, His 14 was the highest contributing histidine ligand in Cu(II) coordination in the ternary complex. The ESEEM signal intensity of His 6 and His 13 labeled peptide (in which only His 14 gives rise to the signal) is approximately 50 % of that of the non-labeled peptide (cf. Aβ(1–16)H6,13[15N] in Figure 6). This signal intensity indicates that ~ 50 % of the peptides in the mixture use His 14 as an equatorial ligand. The ESEEM signal intensities of Aβ(1–16)H6,13[15N] (His 6 non-labeled) and Aβ(1–16)H6,13[15N] (His 13 non-labeled) were ~20 % and ~30 %, respectively. Hence, the percentages of each histidine residue involved as an equatorial ligand in Cu(II), obtained from both single and double labeled peptides were similar. The integrated intensities of each spectrum and the relative contributions from each histidine residue towards the 14N ESEEM signal are tabulated in the supporting information, Tables S3 and S4.

Figure 6.

Three-pulse ESEEM spectra of the nonlabeled and double 15N labeled Aβ(1–16) variants mixed with equimolar amounts of Cu(II) and Zn(II) at 2800 G at pH 7.4(peptide: Cu(II): Zn(II) =1:1:1). Integrated area between 0 – 8 MHz gives the contribution of the nonlabeled histidine residue in double labeled Aβ(1–16) variants for component I in Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) complex. Aβ(1–16)H13,14[15N], Aβ(1–16)H6,14[15N], Aβ(1–16)H6,13[15N] denote peptides where His 13/14, His 6/14, and His 6/13 are labeled with 15N, respectively.

The integrated intensity of the DQ peak depends on the number of 14N ESEEM active histidine residues.40 Hence, the double quantum signal was weak in the doubly labeled peptides as only one 14N ESEEM active histidine residue is present. The comparison between the single and the double labeled peptide showed that in the single label the DQ integrated intensity is larger. If there is just single histidine coordination the DQ intensity would remain similar between the single and the double labeled peptides. Therefore, the simultaneous coordination of two histidine residues in component I of the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) ternary complex is preserved as in the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) binary complex.24–26

HYSCORE experiments were carried out in nonlabeled and labeled Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) at physiological pH and at the magnetic field of 3360 G. The spectra obtained showed the same frequency patterns as in the -Cu(II) complex26–27, indicating that despite the presence of Zn(II), the coordination of Cu(II) remains essentially unchanged (Figure S3). The primary difference between the two sets of spectra was that the intensities of correlation peaks were reduced as Zn(II) replaced approximately 25% of bound Cu(II) at equimolar amounts.

DISCUSSION

Selective Zn(II) competition for component I Cu(II) coordination

Much work has been performed to determine the coordination environments and aggregate forms of Aβ in the presence of metal ions, such as Cu(II) and Zn(II). However, multiple metal ion interactions in Aβ are not well understood. The changes in Cu(II) coordination modes in the presence of Zn(II) in prion protein were examined using CW-ESR53 and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS).54 These results in Aβ(1–16)shows the usefulness of ESEEM to elucidate molecular level details of metal ion competition and coordination. These kinds of experiments are important as multiple metal ions coexist in an in-vivo environment. Using CW-ESR and spectral simulations we established that Zn(II) competes only with component I at physiological pH. Our CW-ESR and simulations revealed that at excess amounts of Zn(II), component II becomes the most significant coordination mode. In brain tissues affected with Alzheimer’s disease zinc has a higher concentration than copper.9 Hence, it will be critical to understand the microscopic details of component II coordination.

Change in component I Cu(II) coordination in the Aβ(1–16) in the presence of Zn(II)

The ESEEM results show that at the physiological pH proportions of peptides coordinated through histidine residues in the equatorial plane is in the order of His 14 > His 13 > His 6. These contributions were significantly different from the contributions reported for component I in Cu(II)- Aβ(1–16) binary complex. Previous work done in our group reported that the order for the binary complex was His 14 ~ His 6 > His 13.26 This is the first investigation reporting the contributions of each histidine residue in the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)/Zn(II) ternary complex. These results suggest the importance of His 14 in Cu(II) coordination in the presence of Zn(II).

Damante et. al.55 in their work done using the Aβ(1–16)-polyethyleneglycol-ylated peptide suggested that the addition of Zn(II) does not liberate Cu(II) ion, but modifies the metal ion distribution in Aβ(1–16). In our findings Zn(II) can partially substitute (~25 %) bound Cu(II) from Aβ(1–16) at equimolar concentrations. Also present work adds critical details of the redistribution of Cu(II). Using the proportions of each histidine residue involved in the Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II), the proportion of peptides in each component was calculated (cf. Figure S4 in supporting information for more details).26 Figure 7 shows the overall coordination environment of Cu(II) in Aβ(1–16) in the presence and absence of one equivalent of Zn(II). Notably, all the Cu(II) ions in subcomponent IA, in which the metal ion is simultaneously coordinated to His 6 and His 13, are replaced by Zn(II). The proportion of Cu(II) coordinated peptides in subcomponent IB is decreased, while the number of peptides in subcomponent IC is increased. These observations can be rationalized using the individual affinities of histidine residues towards Cu(II). The affinity of each histidine residue is in the order of His 14 > His 13 ~ His 6.26 This order would suggest Zn(II) is more likely to remove Cu(II) coordinated to His 6 and His 13, rather than His 14. Hence, Zn(II) is most likely to substitute Cu(II) in the sub component IA.

Figure 7.

Overall population distribution of Cu(II) binding modes in Aβ(1–16) in the presence and the absence of Zn(II) at physiological pH. The proportion of Subcomponent IC, which may inhibit the formation of ordered fibrillar forms, is increased. Subcomponent IA is no longer present in the presence of Zn(II) and IB proportion is decreased.

Information on Cu(II) and Zn(II) coordination in Aβ will help establish the conformational preferences and structure of the N-terminal. This insight is crucial because current models of structure are in the absence of any metal ions. Furthermore, these results are also likely to guide rational structure based design of metal chelates as therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease.56–58

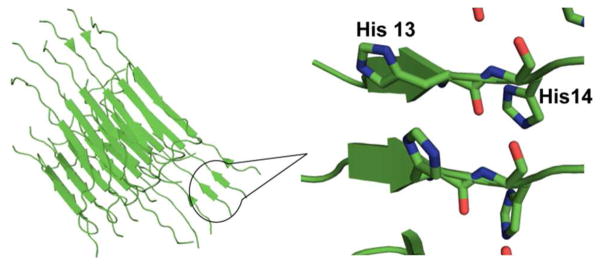

Physiological Importance of Simultaneous His-13 and His-14 Coordination

It is known that at greater than equimolar concentrations the proportion of amorphous aggregates is greater than the ordered fibrillar aggregates.15 Previously, we had proposed that simultaneous His13-His 14 coordination (subcomponent IC) might be the genesis of this effect. Simultaneous coordination His13-His14 to Cu(II) is expected to prevent the formation of ordered β-sheet structures, as the side chains of the histidine residues would be forced to be on the same side. In the presence of Zn(II) the proportion of subcomponent IC increases. It has also, been postulated that a salt-bridge between His 13 and Asp 23 is important for the formation of a key intermediate towards the formation of ordered fibrils. 60–61 Zn(II) or Cu(II) coordination to His 13 even at very small concentrations may disrupt the salt bridge leading to the formation of disordered amorphous aggregates, rather than the ordered. We performed AFM imaging in order to test these hypotheses. In the presence of Zn(II), amyloid-β forms more amorphous aggregates (Figure S5). These AFM experiments were carried out using Aβ(1–40), as this variant contains the hydrophobic region necessary for aggregation of the peptide, which is absent in Aβ(1–16). In general, when the metal ion concentration increases, the probability of forming fibrillar aggregates is decreased. These results suggest that metal-ion coordination to His 13 likely plays a decisive role in dictating the morphology of the aggregates. It would be fascinating to directly monitor the disruption of the His13-Asp23 salt-bridge by solid state NMR.62

CONCLUSIONS

We used a well-known metal binding peptide, Aβ which is involved in the Alzheimer’s disease to study the metal binding competition between Cu(II) and Zn(II). The two metal ions, Cu(II) and Zn(II), have different affinities towards Aβ(1–16), and even at large excess of Zn(II), ~ 60% of Cu(II) is still bound to Aβ(1–16). Interestingly Zn(II) was only able to replace Cu(II) coordinated in component I, while component II bound Cu(II) resisted the Zn(II) substitution. Subcomponent IC in which His 13 and 14 are equatorially coordinated to Cu(II) ion becomes the most significant coordination mode. This is a very interesting observation as subcomponent IC might be responsible for the formation of amorphous aggregates. This work shows the ability of ESEEM to obtain molecular level information of metal ion coordination and competition. Such molecular level details of metal ion coordination may ultimately pave the way to understand the formation of aggregates of different morphologies, and ultimately the toxicity associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Supplementary Material

Figure 8.

Location of His 13 and His 14 in the fibrillar structure of Aβ(1–40)59. (PDB ID: 2LMN)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (5R01NS053788), and a National Science Foundation (MCB 1157712) grant. The Bruker ElexSys E680 was purchased from the funds from National Institutes of Health grant 1S10RR028701. We are grateful to the peptide synthesis facility at University of Pittsburgh, for peptide preparation. We also thank Dr. Byong-kyu Shin and Brian Michael for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION PARAGRAPH

Proportions of component I and II at different Zn(II) concentrations (Figure S1, Table S1), CW simulations (Figure S2) ESR parameters for CW simulation (Table S2), Intensities of the 14N-ESEEM and the 1H-ESEEM region in the three-pulse ESEEM spectra (Table S3, Table S4), HYSCORE spectra (Figure S3), Method of calculating subcomponent percentages (Figure S4), AFM images (Figure S5) Web at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Maret W. Metalloproteomics, Metalloproteomes, and the Annotation of Metalloproteins. Metallomics. 2010;2:117–125. doi: 10.1039/b915804a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan JH, Lutsenko S. Copper Transport in Mammalian Cells: Special Care for a Metal with Special Needs. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25461–25465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.031286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turski ML, Thiele DJ. New Roles for Copper Metabolism in Cell Proliferation, Signaling, and Disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:717–721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800055200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim BE, Nevitt T, Thiele DJ. Mechanisms for Copper Acquisition, Distribution and Regulation. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:176–185. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ducea JA, Bush AI. Biological Metals and Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Therapeutics and Diagnostics. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010;92:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattson MP. Pathways Towards and Away from Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guy M, David K, Howard C, Bradley H, Jr, Claudia JCK, William K, Walter K, Jennifer M, Richard M, John M, Martin R, Philip S, et al. The Diagnosis of Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovell MA, Robertsona JD, Teesdaleb WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. Copper, Iron and Zinc in Alzheimer’s Disease Senile Plaques. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faller P, Hureau C. Bioinorganic Chemistry of Copper and Zinc Ions Coordinated to Amyloid-β Peptide. Dalton Trans. 2009:1080–1094. doi: 10.1039/b813398k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kepp KP. Bioinorganic Chemistry of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem Rev. 2012;112:5193–5239. doi: 10.1021/cr300009x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hureaua C, Dorlet P. Coordination of Redox Active Metal Ions to the Amyloid Precursor Protein and to Amyloid-β Peptides Involved in Alzheimer Disease. Part 2: Dependence of Cu(II) Binding Sites with Aβ Sequences. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2012;256:2175–2187. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morante S. The Role of Metals in β-Amyloid Peptide Aggregation: X-Ray Spectroscopy and Numerical Simulations. Current Alzheimer’s Research. 2008;5:508–524. doi: 10.2174/156720508786898505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viles JH. Metal Ions and Amyloid Fiber Formation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Copper, Zinc and Iron in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Prion Diseases. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2012;256:2271–2284. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jun S, Gillespie JR, Shin BK, Saxena S. The Second Cu(II)-Binding Site in a Proton-Rich Environment Interferes with the Aggregation of Amyloid-β(1–40) into Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10724–10732. doi: 10.1021/bi9012935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noy D, Solomonov I, Sinkevich O, Arad T, Kjaer K, Sagi I. Zinc-Amyloid β Interactions on a Millisecond Time-Scale Stabilize Non-Fibrillar Alzheimer-Related Species. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1376–1383. doi: 10.1021/ja076282l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garai K, Sahoo B, Kaushalya SK, Desai R, Maiti S. Zinc Lowers Amyloid-β Toxicity by Selectively Precipitating Aggregation Intermediates. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10655–10663. doi: 10.1021/bi700798b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamley IW. The Amyloid Beta Peptide: A Chemist’s Perspective. Role in Alzheimer’s and Fibrillization. Chem Rev. 2012;112:5147–5192. doi: 10.1021/cr3000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damante CA, Ősz K, Nagy Zn, Pappalardo G, Grasso G, Impellizzeri G, Rizzarelli E, Sóvágó I. Metal Loading Capacity of Aβ N-Terminus: A Combined Potentiometric and Spectroscopic Study of Zinc(II) Complexes with Aβ(1–16) Its Short or Mutated Peptide Fragments and Its Polyethylene Glycol–Ylated Analogue. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:10405–10415. doi: 10.1021/ic9012334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karr JW, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. Amyloid-β Binds Cu2+ in a Mononuclear Metal Ion Binding Site. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13534–13538. doi: 10.1021/ja0488028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karr JW, Akintoye H, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. N-Terminal Deletions Modify the Cu2+ Binding Site in Amyloid-β. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5478–5487. doi: 10.1021/bi047611e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karr JW, Szalai VA. Cu(Ii) Binding to Monomeric, Oligomeric, and Fibrillar Forms of the Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-β Peptide. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5006–5016. doi: 10.1021/bi702423h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syme CD, Nadal RC, Rigby SEJ, Viles JH. Copper Binding to the Amyloid-β (Aβ) Peptide Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18169–18177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drew SC, Noble CJ, Masters CL, Hanson GR, Barnham KJ. Pleomorphic Copper Coordination by Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-β Peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1195–1207. doi: 10.1021/ja808073b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorlet P, Gambarelli S, Faller P, Hureau C. Pulse Epr Spectroscopy Reveals the Coordination Sphere of Copper(II) Ions in the 1–16 Amyloid-β Peptide: A Key Role of the First Two N-Terminus Residues. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:9273–9276. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin B-k, Saxena S. Substantial Contribution of the Two Imidazole Rings of the His13–His14 Dyad to Cu(II) Binding in Amyloid-β(1–16) at Physiological pH and Its Significance. J Phys Chem A. 2011;115:9590–9602. doi: 10.1021/jp200379m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin B-k, Saxena S. Direct Evidence That All Three Histidine Residues Coordinate to Cu(II) in Amyloid-β 1–16. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9117–9123. doi: 10.1021/bi801014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunderson WA, Hernández-Guzmán J, Karr JW, Sun L, Szalai VA, Warncke K. Local Structure and Global Patterning of Cu2+ Binding in Fibrillar Amyloid-β [Aβ(1–40)] Protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18330–18337. doi: 10.1021/ja306946q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minicozzi V, Stellato F, Comai M, Serra MD, Potrich C, Meyer-Klaucke W, Morante S. Identifying the Minimal Copper- and Zinc-Binding Site Sequence in Amyloid-β Peptides. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10784–10792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozina SA, Zirahc S, Rebuffatc S, Hoad GHB, Debey P. Zinc Binding to Alzheimer’s Aβ(1–16) Peptide Results in Stable Soluble Complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:959–964. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zirah SV, Kozin SA, Mazur AK, Blond A, Cheminant M, Ségalas-Milazzo I, Debey P, Rebuffat S. Structural Changes of Region 1 – 16 of the Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid β - Peptide Upon Zinc Binding and in-Vitro Aging. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2151–2161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syme CD, Viles JH. Solution 1H NMR Investigation of Zn2+ and Cd2+ Binding to Amyloid-Beta Peptide (Aβ) of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;1764, 246:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danielsson J, Pierattelli R, Banci L, Grälund A. High-Resolution Nmr Studies of the Zinc-Binding Site of the Alzheimer’s Amyloid Beta-Peptide. FEBS J. 2007;274:46–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsvetkov PO, Kulikova AA, Golovin AV, Tkachev YV, Archakov AI, Kozin SA, Makarov AA. Minimal Zn2+ Binding Site of Amyloid-B. Biophys J. 2010;99:L84–L86. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merrifield RB. Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis. I. The Synthesis of a Tetrapeptide. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85(14):2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fields GB, Noble RL. Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis Utilizing 9- Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl Amino Acids. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1990;35:161–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fauth JM, Schweiger A, Braunschweiler L, Forrer J, Ernst RR. Elimination of Unwanted Echoes and Reduction of Dead Time in Three-Pulse Electron Spin-Echo Spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1986;66:74–85. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gemperle C, Aebli G, Schweiger A, Ernst RR. Phase Cycling in Pulse EPR. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1990;88:241–256. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCracken J, Peisach J, Dooley DM. Cu(II) Coordination Chemistry of Amine Oxidases. Pulsed Epr Studies of Histidine Imidazole, Water, and Exogenous Ligand Coordination. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:4064–4072. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCracken J, Pember S, Benkovic SJ, Villafranca JJ, Miller RJ, Peisach J. Electron Spin-Echo Studies of the Copper Binding Site in Phenylalanine Hydroxylase from Chromobacterium Violaceum. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:1069–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCracken J, Desai PR, Papadopoulos NJ, Villafranca JJ, Peisach J. Electron Spin-Echo Studies of the Copper(II) Binding Sites in Dopamine β-Hydroxylase. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4133–4137. doi: 10.1021/bi00411a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang F, McCracken J, Peisach J. Nuclear Quadrupole Interactions in Copper(II)- Diethylenetriamine-Substituted Imidazole Complexes and in Copper(Ii) Proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:9035–9044. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCracken J, Peisach J, Cote CE, McGuirl MA, Dooley DM. Pulsed Epr Studies of the Semiquinone State of Copper-Containing Amine Oxidases. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3715–3720. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flanagan HL, Singel DJ. Analysis of Nitrogen-14 Eseem Patterns of Randomly Oriented Solids. J Chem Phys. 1987;87:5606–5616. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mims WB. Envelope Modulation in Spin-Echo Experiments. Phys Rev B. 1972;5:2409–2419. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai A, Flanagan HL, Singel DJ. Multifrequency Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation in S=1/2, I=1/2 Systems: Analysis of the Spectral Amplitudes, Line Shapes, and Linewidths. J Chem Phys. 1988;89:7161–7166. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang XS, Diner BA, Larsen BS, Gilchrist ML, Jr, Lorigan GA, Britt RD. Identification of Histidine at the Catalytic Site of the Photosynthetic Oxygen-Evolving Complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:704–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh V, Zhu Z, Davidson VL, McCracken J. Characterization of the Tryptophan Tryptophyl-Semiquinone Catalytic Intermediate of Methylamine Dehydrogenase by Electron Spin-Echo Envelope Modulation Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:931–938. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoll S, Calle C, Mitrikas G, Schweiger A. Peak Suppression in ESEEM Spectra of Multinuclear Spin Systems. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2005;177:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peisach J, Blumberg WE. Structural Implications Derived from the Analysis of EPR Spectra of Natural and Artificial Copper Proteins. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1974;165:691–708. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burns CS, Aronoff-Spencer E, Dunham CM, Lario P, Avdievich NI, Antholine WE, Olmstead MM, Vrielink A, Gerfen GJ, Peisach J, Scott WG, et al. Molecular Features of the Copper Binding Sites in the Octarepeat Domain of the Prion Protein. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3991–4001. doi: 10.1021/bi011922x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deligiannakis Y, Louloudi M, Hadjiliadis N. Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation (ESEEM) Spectroscopy as a Tool to Investigate the Coordination Environment of Metal Centers. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2000;204:1–112. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walter ED, Stevens DJ, Visconte MP, Millhauser GL. The Prion Protein Is a Combined Zinc and Copper Binding Protein: Zn2+ Alters the Distribution of Cu2+ Coordination Modes. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15440–15441. doi: 10.1021/ja077146j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stellato F, Spevacek A, Proux O, Minicozzi V, Millhauser G, Morante S. Zinc Modulates Copper Coordination Mode in Prion Protein Octa-Repeat Subdomains. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:1259–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0713-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Damante CA, Ősz K, Nagy ZN, Grasso G, Pappalardo G, Rizzarelli E, Sóvágó I. Zn2+’S Ability to Alter the Distribution of Cu2+ among the Available Binding Sites of Aβ(1–16)-Polyethylenglycol-Ylated Peptide: Implications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:5342–5350. doi: 10.1021/ic101537m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braymer JJ, Choi JS, DeToma AS, Wang C, Nam K, Kampf JW, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Development of Bifunctional Stilbene Derivatives for Targeting and Modulating Metal-Amyloid-β Species. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:10724–10734. doi: 10.1021/ic2012205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones MR, Service EL, Thompson JR, Wang MCP, Kimsey IJ, DeToma AS, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH, Storr T. Dual-Function Triazole–Pyridine Derivatives as Inhibitors of Metal-Induced Amyloid-β Aggregation. Metallomics. 2012;4:910–920. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20113e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Collin F, Sasaki I, Eury Hln, Faller P, Hureau C. Pt(II) Compounds Interplay with Cu(II) and Zn(II) Coordination to the Amyloid-B Peptide Has Metal Specific Consequences on Deleterious Processes Associated to Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem Commun. 2013;49:2130–2132. doi: 10.1039/c3cc38537j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petkova AT, Yau WM, Tycko R. Experimental Constraints on Quaternary Structure in Alzheimer’s B-Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kirkitadze MD, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Identification and Characterization of Key Kinetic Intermediates in Amyloid Beta-Protein Fibrillogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:1103–1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fraser PE, Nguyen JT, Surewicz WK, Kirschner DA. pH-Dependent Structural Transitions of Alzheimer Amyloid Peptides. Biophysical J. 1991;60:1190–1201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mithu VS, Sarkar B, Bhowmik D, Chandrakesan M, Maiti S, Madhu PK. Zn++ Binding Disrupts the Asp23-Lys28 Salt Bridge without Altering the Hairpin-Shaped Cross-β Structure of Aβ42 Amyloid Aggregates. Biophys J. 2011;101:2825–2832. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.