Abstract

The purpose of this article is to describe Fortalezas Familiares (FF; Family Strengths), a community-based prevention program designed to address relational family processes and promote wellbeing among Latino families when a mother has depression. Although depression in Latina women is becoming increasingly recognized, risk and protective mechanisms associated with children’s outcomes when a mother has depression are not well understood for Latino families. We begin by reviewing the literature on risk and protective psychosocial mechanisms by which maternal depression may affect Latino youth, using family systems theory and a developmental psychopathology framework with an emphasis on sociocultural factors shaping family processes. Next, we describe the theoretical basis and development of the FF program, a community-based 12-week intervention for Latina immigrant women with depression, other caregivers, and their children. Throughout this article, we use a case study to illustrate a Latina mother’s vulnerability to depression and the family’s response to the FF program. Recommendations for future research and practice include consideration of sociocultural processes in shaping both outcomes of Latino families and their response to interventions.

Keywords: maternal depression, Latinos, immigrants, child mental health, family intervention

There is an acute need for family based interventions when mothers have depression (Beardslee, 2002). Over 25 years of research shows that children of mothers with depression are more likely to develop social impairment and mental health problems (i.e., major depression, anxiety disorders, and substance dependence), as well as physical disability and medical conditions that persist into adulthood, compared to children of mothers without depression (Timko et al., 2009; Weissman et al., 2006). Because the majority of this research has been conducted with predominantly White populations, researchers and practitioners have been limited in their ability to address the needs of socioeconomically disadvantaged families, where rates of depression are particularly elevated (Cardemil, Kim, Pinedo, & Miller, 2005). Thus, understanding the relationship between maternal depression and family functioning among minority families, such as Latino immigrant families, and the associated sociocultural pathways to risk and resilience, therefore, should be a priority for researchers who are interested in developing culturally-appropriate interventions for this vulnerable population. Although depression varies by severity and timing of onset, in this article, we focus on mothers who experience moderate to severe symptoms of depression during their child’s pre-adolescent or adolescent years, to highlight the association of these symptoms with other family processes, and their impact on a particularly vulnerable stage of child development.

Keeping Families Strong (Author et al., 2008), an evidence-derived family based intervention developed for White and African American families, has now been adapted for Latino families in response to the growing literature on depression in Latina women. The adapted intervention, Fortalezas Familiares (FF; Family Strengths) was piloted over three administrations in a community-based, multi-family group setting. We discuss how this intervention addresses the needs of Latino families and their response to the intervention.

Despite research showing that many newly arrived Latino immigrants have lower rates of depression, their risk for depression increases the longer they live in the United States (Alegría et al., 2007). In addition, when immigrant mothers succumb to depression, they have a more chronic course of depression compared to White women (Breslau, Kendler, Su, Gaxiola-Aguilar, & Kessler, 2005), and coping may be less effective in a foreign culture, where traditional support systems may not be in place (Busch, Bohon, & Kim, 2010). Because family cohesion and interdependence are highly valued by many Latino families (Falicov, 2003), maternal depression has significant implications for the wellbeing of children of immigrant parents.

Factors contributing to depression among Latina women include family separation, exposure to traumatic experiences, acculturative stress, racism and discrimination, and poverty (Heilemann, Coffey-Love, & Frutos, 2004). Relational factors and patterns are mutually influential in Latina depression as well, and include marital dissatisfaction, parent-child conflict, and coping with interpersonal losses and transitions both in the country of origin and the host country (Falicov, 2003). These factors are illustrated in the following case study of Mariana1, a 33 year-old Mexican mother and wife:

Mariana first experienced depression when she was 11 years old, after being sexually abused by a neighbor while her single mother worked outside the home. At the age of 20, Mariana migrated to the United States alone in search of better economic opportunities, but she struggled to adapt to her new environment without her mother’s support. Three years later, her boyfriend abandoned her after discovering that she was pregnant. Soon after Antonio was born, she married Joaquín, a kind man who lovingly raised her son. Mariana and Joaquín have experienced a series of financial and marital stressors, and in the past two years, Mariana’s mother passed away in Mexico, and Antonio’s biological father returned to start a relationship with his, now, 10 year-old son. Mariana’s regret over leaving her mother in Mexico, and fear of having to disclose the truth to Antonio about his biological father, intensified her depression. Joaquín could not understand why she was increasingly withdrawing from the family, and he responded in turn by being critical and distant. Interactions grew tense between Joaquín and Mariana, and the children grew angry and worried as they watched their family fall apart. In one attempt to get her mother’s attention, Amanda, her 7 year-old daughter, wrote a poem to Mariana but was saddened when her gesture went unacknowledged for days.

Although research is beginning to reveal why Latina women, like Mariana, are vulnerable to depression, mechanisms of risk and resilience for children with a mother with depression are less well understood for Latinos, relative to Whites (Corona, Lekfowitz, Sigman, & Romo, 2005). Consequently, theory- and culturally- driven interventions for these families are scarce.

Our conceptual framework of maternal depression is informed by systems theory and developmental psychopathology. Systems theory is founded on the premise that persistent change or stress in the family will prompt family members to reorganize in order to adapt. The family’s adaptability to these changes will in turn affect the level of change or stress, so that rigid family patterns will accelerate undesirable changes, and flexible family patterns will decelerate these changes (Baker, Seltzer, & Greenberg, 2011; Nichols & Schwartz, 2008). In addition, our work on Latino families is guided by developmental psychopathology, which examines negative and positive adjustment as a consequence of the dynamic interplay among risk and protective factors over time (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). We focus on sociocultural risk and protective factors affecting family processes for Latino children, given the centrality of family life in Latino culture (Corona et al., 2005) and the vulnerability of family life when parental and family stressors are present (Beardslee, 2002; Author et al., 2008). We focus on pre-adolescents and adolescents because of their (a) increased risk for internalizing symptoms, particularly for girls (Cicchetti & Toth, 2008); and (b) heightened sensitivity to the needs of the family (Crean, 2008; Prado et al., 2008; Zayas, Lester, Cabassa, & Fortuna, 2005).

Sociocultural Mechanisms of Risk in Maternal Depression

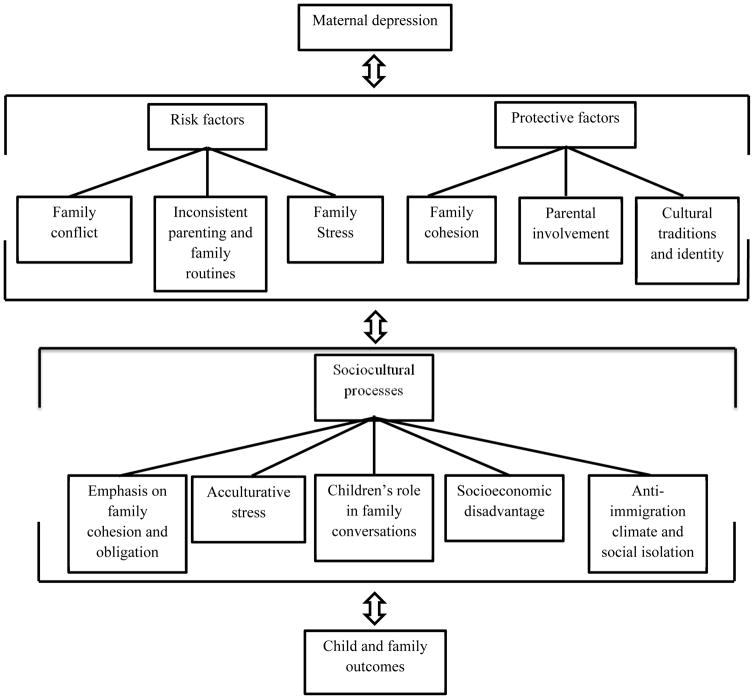

Sociocultural processes affecting the family system, such as differential acculturation pace between parents and children, cultural emphasis on family obligation and cohesion, and parenting practices that are dissonant with the host culture, among others, shape the resources that families have to cope with maternal depression. These processes exacerbate risk factors associated with maternal depression—family conflict, inconsistent routines, and isolation—or enhance protective factors associated with resilience in children when a mother has depression—family cohesion and involvement, cultural traditions and bicultural orientation, and strong social ties—and are described within each one of these family risk and protective factors (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms and sociocultural processes influencing outcomes for Latino families affected by maternal depression

Family Conflict

Conflict in the parent-child and marital relationship is often a consequence (i.e., way of coping) and a contributing force of maternal depression. Empirical evidence with 101 low-income, Puerto Rican and Dominican women with children in Head Start suggests that mothers with depression are more irritable and praise their children less and criticize them more, compared to mothers without depression (Plano, Zayas, & Busch-Rossnagel, 2005). Conversely, research with 111 low income, Mexican and Central American mothers in the United States and their adolescent children shows that mothers with depression report being less satisfied with their family interactions than Latina mothers without depression, in turn decreasing warmth and nurturance and increasing conflict (Corona et al., 2005). These studies suggest circular relational patterns with maternal depression, with family relations both increasing risk for maternal depression and increasing risk for children’s adjustment when a mother has depression.

Family conflict may be particularly burdensome for Latino immigrant families because many of these families value cohesion and children’s dependence on their mother (Corona et al., 2005). In a study of 329 Latino adolescents of predominant Mexican descent in the southwestern United States, adolescents were found to experience more negative effects from family conflict, including internalizing and externalizing symptoms, than non-Latino adolescents (Crean, 2008; Prado et al., 2008). In a review of the literature on Latino youth suicidality, Zayas and colleagues (2005) described Latina adolescents who attempt suicide as being more likely to attribute their attempts to family problems rather than peer problems, relative to non-Latina youth.

Although intergenerational conflict is assumed to be normative, and to increase when a mother has depression, it can be exacerbated in immigrant families in which adolescents attempt to individuate as a result of greater acculturation to U.S. norms and expectations, relative to their parents (Chapman & Perreira, 2005). As children internalize the values of the host culture at a faster pace than their parents, family conflict may increase, parental authority may decrease, and children may increasingly express disconnection over parents’ ways (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). In addition, immigrant parents who once relied on their children for language and cultural brokering may handle the resulting role reversal by attempting to curtail children’s growing independence (Prado et al., 2008). Thus, acculturative stress is associated with family stress in immigrant families (Falicov, 2003), and may heighten conflict and maternal depression.

Another type of family conflict powerfully connected with maternal depression is marital conflict. Although a significant number of adult immigrants are in a married or partnered relationship (Falicov, 2003), marital dissatisfaction may be high due to acculturative stress, financial burden, and unanticipated changes to traditional gender norms (Busch et al., 2010). In a literature review of adaptation among Latino and Asian immigrant families in the United States, Busch and colleagues (2010) described the role of acculturation in marital conflict, explained by women acculturating more rapidly than men into U.S. society and often gaining economic power when they join the workforce to support the family’s income. Conflict ensues, and the mother’s stress increases, when the father perceives that her increasing independence comes at the expense of her caretaking responsibilities (Busch et al., 2010; Sarmiento & Cardemil, 2009).

As illustrated in our case study, family conflict can undermine the marital relationship, exacerbate the mother’s depression, and strain the family’s resources to cope with changes in the family. Family conflict decreases parents’ responsiveness to their children’s needs, and increases children’s perceived responsibility for the wellbeing of the family (Beardslee, 2002). Further, family conflict can reduce family conversations about day-to-day events, family problems, and about the mother’s depression. Moreover, cultural norms may restrict children’s role in difficult family conversations (Falicov, 2003), further preventing children from expressing concerns about their mother’s depression and the family (Author et al., 2008). Language differences between parents and children can also limit family communication, as when parents are largely Spanish-dominant and their children are largely English-dominant. As a consequence, family members lack a framework to understand the mother’s depression and related family stressors and cope on their own with their sorrow, anger, fear, and confusion (Author et al., 2008).

Parenting Practices and Family Routines

Depressive symptoms and negative family patterns can undermine the mother’s confidence in her ability to parent her children, that is, to establish rules and expectations for their children’s behavior (Author et al., 2008). Latina mothers with depression may feel even less secure in their parenting skills because their standards of acceptable discipline (i.e., spanking) may be incompatible with those of U.S. society (Falicov, 2003). Further, immigrant parents may experience a loss of authority when their children serve as brokers of U.S. culture. Thus, when parents are not able to manage their children’s behavior consistently, they lack the authority to enforce stable routines (e.g., meals, bedtime) and activities for the family. Research shows that inconsistent parenting and routines associated with maternal depression have been linked with higher risk for substance abuse in Latino children (Corona et al., 2005).

While some children respond to their mothers’ inconsistent parenting by not complying with rules, others assume significant family obligations. Although in general, family obligations are considered protective for Latino children because they elevate children’s place within the family (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999), a stressful emotional climate coupled with a motivation to restore the family’s wellbeing can make these obligations burdensome (Jurkovic et al., 2004).

Family stress and isolation

As illustrated in our case study, family stress can strain already limited resources for the family when a mother has depression, including time for caregiving, monitoring, supervision, and engaging in everyday family routines (Author et al., 2008). For example, many immigrant parents work multiple, low-paying, and unstable jobs to manage financially (Jurkovic et al., 2004). Mothers are also now more likely to work outside of the home than they did in their country of origin (Falicov, 2003). Thus, economic stressors on Latino families may limit parents’ involvement in their children’s lives (Jurkovic et al., 2004).

Economic disadvantage is particularly elevated for families affected by other social stressors, such as increasingly restrictive immigration policies in the United States. Intimidation, detention, and deportation have led to limited employment opportunities, loss of a parent’s income, and financial stress, as well as family separation (Author et al., 2012). In addition, racial and ethnic discrimination has been associated with higher levels of stress and depression for Latino children (Cardemil et al., 2005). However, because many immigrant Latino parents did not grow up experiencing ethnic discrimination in their native country, they may not know how to help their children cope with this type of discrimination (Hughes, 2003).

Social isolation can deprive children from positive role models and activities outside the family, which are known to protect families during times of stress (Author, 2008). Among Latino immigrant families, decreased public exposure and social participation may derive from fear of deportation and intimidation (Jurkovic et al., 2004; Author et al., 2012), and also from parents’ perception that their values and expectations are at odds with those of the host culture (Prado et al., 2008). Alarming is that as children move closer to the host culture, their isolated parents become less involved in their children’s lives and in their peer relationships (Prado et al., 2008).

Building Family Resilience

Resilience can be achieved in spite of the risks reviewed in this article, by drawing upon the family and cultural strengths and assets that may already exist but that families may not know how to access (see Figure 1). These include family cohesion, nuclear and extended family involvement, cultural traditions, bicultural orientation, and community supports.

In general, family cohesion and involvement are important sources of resilience for Latino children facing disruptions in family functioning and parental depression. Familism, defined as “the emotional bonding that family members have towards one another” (Rivera et al., 2008, p. 258), is related to feelings of reciprocity, loyalty, and cohesion, which in turn are related to lower levels of psychological distress among Latinos (Chapman & Perreira, 2005). The positive emotional bond associated with familism can be strengthened through family activities and routines that connect parents with depression and their children.

Similarly, parental involvement, in the form of warmth, communication, and monitoring, prepares children to cope with their mother’s depression, negative family interactions, and other stressors, such as discrimination (Hughes, 2003), and can help to mitigate children’s risk for internalizing symptoms, as well as exposure to deviant peers (Berger Cardoso & Thompson, 2010). Involvement can also come from extended family members (Falicov, 2003), and can help Latino children develop more positive attitudes towards family life (Chapman & Perreira, 2005).

In addition to family cohesion and involvement, cultural traditions can be a significant resource for Latino immigrant families (Berger Cardoso & Thompson, 2010). Participation in spiritual, folk, and cultural rituals and traditions that reinforce families’ cultural heritage and connect family members through their shared immigration history can strengthen loyalty and weaken the effects of emotional and societal stressors (Berger Cardoso & Thompson, 2010; Chapman & Perreira, 2005; Imber-Black & Roberts, 1998). In fact, D’Angelo and colleagues (2009) found in their intervention with Puerto Rican and Dominican mothers with depression in the United States that cultural rituals, such as religious coping or faith, can help Latino immigrant families cope with maternal depression and loss by providing meaning to their experience and a source of comfort.

Similarly, bicultural identity can protect children facing adversity by allowing them to draw upon the resources and supportive outlets of the two cultures (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2011). Biculturalism has been linked with optimal functioning for children, including lower depression and better academic and interpersonal adjustment (Berger Cardoso & Thompson, 2010). Notably, when both youth and parents are bicultural there is greater family cohesion, adaptability, and loyalty, compared to when only youth are bicultural (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006).

Finally, Latino immigrants in the United States generally have strong social ties within their ethnic enclaves that facilitate the procurement of employment, housing, and other resources (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). These ties have been associated with parental monitoring, norm socialization, and children’s academic success (Prado et al., 2008), and have the potential to decrease social isolation and to promote children’s efficacy when a mother has depression.

Addressing Family Processes Associated with Maternal Depression

Because maternal depression is interpersonal in nature and is both shaped by and shapes family interactions, interventions should be developed at the family level and should incorporate the theorized sociocultural processes that influence Latino families’ functioning in the context of maternal depression. First, to create change at the level of the family, the whole family needs to be part of the intervention. Second, psychoeducation about depression and associated family processes needs to be an integral part of any intervention so that family members have a framework for recognizing and understanding the family interactions contributing to the mother’s emotional response, and the emerging family interactions attempting to manage that response (Author et al., 2008). Similarly, a family intervention should build family members’ skills and confidence in conflict-resolution, problem-solving and communication, so family members can share their concerns and plan for recovery.

Third, increasing parental involvement and parenting confidence can restore positive interactions, positive emotional bonds, and meet children’s needs for consistency and stable routines. Thus, an intervention needs to help families recognize the value of positive family experiences, and provide the tools to plan and carry out fun activities that increase emotional connection and positive family exchanges. Fourth, because of the acculturative and social stressors affecting many Latinos in the United States, a family intervention needs to educate immigrant parents and youth about acculturative stress and youth experiences of discrimination in the United States, and to enhance family members’ comfort with family conversations about discrimination. Fifth, interventions for maternal depression should also aim to strengthen social ties and support to reduce family isolation. Thus, a multi-family intervention including nuclear and extended family members would be ideally positioned to strengthen parental support, as well as children’s access to supportive and positive role models and development of friendships.

Interventions for Latino Families

Unfortunately, many Latino immigrant families have limited access to culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health services (Cardemil et al., 2005; Sarmiento & Cardemil, 2009). In addition, only two programs specifically designed for Latina mothers with depression have been published to date, Cardemil and colleagues’ (2005) Family Coping Skills Program (FCSP), and D’Angelo and colleagues’ (2008) adapted version of the Preventive Intervention Program for Depression (PIP; Beardslee, Gladstone, Wright, & Cooper, 2003). These time-limited programs primarily use psychoeducation to help mothers deal with negative emotions and decrease stigma (Cardemil et al., 2005), and to increase the family’s shared understanding of depression (D’Angelo et al., 2008). However, FCSP does not include children, and PIP includes only one child in some but not all modules. Thus, interventions that promote children’s resilience and that involve children’s full participation are needed.

We set out to develop Keeping Families Strong (KFS), a clinic-based 10-week multi-family group program for low-income mothers in treatment for depression, other adult caregivers, and all children ages 9–16 (Author et al., 2008; Author et al., 2011). This age range was chosen because of the high risk for the onset of depression in adolescence, and because process-oriented and psychoeducation programs are more effective during this development stage than in younger childhood (Cicchetti & Toth, 2008; Author et al., 2008). Results from a KFS pilot of six White and four African-American predominantly low-income families shows that the program met its goals, with standardized self-report measures of parent, child, and family functioning reporting participants’ (a) greater understanding of depression among family members, (b) enhanced communication, (c) strengthened parenting skills and confidence, (d) effective children’s coping skills, and (e) increased interpersonal warmth and family cohesion.

The KFS program was designed for predominantly low-income, English-speaking families, but did not account for the unique mechanisms associated with outcomes in Latino immigrant families, reviewed in this article. With research showing improved outcomes for Latino families when interventions are adapted for cultural relevance (Cardemil et al., 2005; D’Angelo et al., 2009; Parra Cardona et al., 2012), it was, therefore, critical to culturally and linguistically adapt KFS to increase its effectiveness and acceptability for these families.

The Fortalezas Familiares Program

The adapted program, Fortalezas Familiares (FF; Family Strengths) is composed of 12 concurrent meetings for mothers with depression and other caregivers, and all youth ages 9–18. In addition to the goals of KFS described above, FF aims to promote Latino families’ understanding of (a) the effects of acculturative and immigration stressors on family life, (b) the importance of parental involvement in and monitoring of children’s activities outside the home, and (c) ways to strengthen children’s coping through involvement in cultural traditions, support from extended family, and engagement in ethnic socialization (i.e., cultural pride and coping with discrimination). In addition to a new meeting on these sociocultural processes, FF dedicates a meeting to marital stress because of the large majority of immigrant families involving a married or partnered relationship. Finally, FF is held in a community agency, rather than a mental health clinic, to facilitate family members’ comfort with and access to the program. Because many low-income women experience a chronic course of depression, it was important for FF, and KFS, to be adjunct to their ongoing outpatient treatment of depression.

Program Structure and Format

The FF program was designed to be delivered in a multi-family group format (3–6 families) to create social support across the families, to normalize the experience of depression and reduce stigma, and to enhance learning and problem solving through collaboration (Author et al., 2011). At the beginning of every meeting, families sit around a table and participate in a culturally-representative meal intended to build group cohesion and trust, as well as to promote social support, family engagement, and cultural pride. Finally, a raffle at the end of the night provides positive interactions among family members after their therapeutic meetings.

Members of each family are divided into parent/caregiver and youth groups. The parent/caregiver group includes the mother with depression and another adult caregiver who has regular contact with the family. In FF, 80% of mothers participating to date brought a spouse, and a few also brought their children’s grandmother, aunt, or an adult sibling. Additionally, we expanded the age from 16 to 18 in FF because many older Latino youth live with their parents. Depending on the number and age span of youth in a cycle, the youth group is broken down into two separate groups to address the different developmental needs of younger and older youth.

Similar to KFS, children under nine years of age are provided with childcare. Unlike KFS, however, FF includes programming that was adapted for young children’s learning capabilities. The programmatic focus in the young child groups is on identifying feelings and stressful situations through developmentally appropriate activities such as drawing, acting, reading children’s stories, and relaxation. The young child group varies widely in terms of developmental level and engagement with the therapeutic materials. Thus, this group is not considered to be an active program component.

The parent/caregiver groups are facilitated by mental health providers who are native Spanish speakers with substantial knowledge of Latino culture. For the youth group, facilitators are bilingual in English and Spanish, and all materials are available in both languages to reflect the heterogeneity of language dominance and cultural identification of the youth group.

Program Content

Theoretically, FF is guided by a developmental psychopathology framework in that it aims to target the mechanisms of risk and resilience that interact during critical periods of development, such as adolescence, and that are potentially malleable by a family intervention. The FF Program is also guided by family systems in that the target of change is the family processes that both lead to and are exacerbated by maternal depression. Thus, inclusion of multiple family members is crucial in working through these processes. Therapeutically, FF uses interpersonal and group process, cognitive-behavioral, and narrative models to integrate psychoeducation with meaning-making, self-reflection, and life stories to target risk and protective processes (Author et al., 2008). These combined approaches are adjusted in accordance with the varying developmental needs of each family member. Family systems theory is incorporated throughout the program in a number of ways. First, education and group discussions about depression are couched in the context of family processes. Second, metaphors and a “family circle” activity are used widely to describe how changes in family members’ feelings and in their family relationships lead to family difficulties that are greater than the sum of their parts. Third, and finally, once foundational understanding, skills, and confidence have been developed the program incorporates individual family sessions towards the end of the program and in the booster meetings. These family sessions are intended for families to address their relational patterns and set goals for the future.

In addition, in FF we use action-oriented learning activities to facilitate perspective-taking by participants of different ages and acculturation levels (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2011). We ask participants in the parent and youth groups to create five scenes representative of the experience of Latino parents/youth in the United States, and to act these scenes in front of the other group (M. Bacallao, personal communication, January 31, 2011). One of the scenes created by parents was of a parent being subjected to abuse in the workplace by a Latino supervisor with “papers”; a scene created by youth was being teased at school for having an accent. Afterwards, participants share with the opposite group, and later with their own group, what they learned from the scenes, and how they connected their new understanding to their family experiences.

Program meetings are sequenced to move group members from self-awareness to understanding of depression, and from coping, to competence and cohesion (see Table 1). During the first two meetings, group members share their family experiences and personal hardships and learn about the relationship between maternal depression and family functioning. Children in particular learn new coping mechanisms such as challenging negative thoughts, seeking support from a trusted person, and engaging in perspective-taking (meeting 2). In meeting 3, group members learn about risk and protective factors for youth in multi-stressed families. Meeting 4 introduces them to the challenges of adolescence for many Latino youth, including negative peer influences, acculturative stress, parent-child cultural separation, and discrimination at school.

Table 1.

Content of FF Parent/Caregiver and Youth Groups

| Meeting | Parent Program | Youth Program |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction and family sharing | Introduction and family sharing |

| Identifying hopes and goals | Identifying strengths, hopes and goals | |

| 2 | Understanding depression | Understanding stress |

| Depression, thoughts and feelings | Helpful and hurtful thoughts | |

| 3 | Effects of depression on the family | Family stress and strengths |

| Resilience in children | Effects of depression on the family | |

| 4 | Growing up in the United States | Growing up in the United States |

| Integrating two cultures | Integrating two cultures | |

| 5 | Creating positive family experiences | Creating positive family experiences |

| Family activities and using praise | Changing kids’ and families’ worlds | |

| 6 | Building positive communication | Building positive communication |

| Listening, Responding, “I” Statements | Positive statements/“I” Statements | |

| 7 | Managing children’s behavior | Family responsibilities |

| Clear, calm, and consistent strategies | Family obligations | |

| 8 | Conflict resolution | Conflict resolution |

| Working through marital conflict | Negotiating conflict in a different culture | |

| 9 | Preparing for family meeting | Preparing for family meeting |

| 10 | Family meeting | Family meeting |

| 11 | Processing the family meeting and preparing for future meetings | Processing the family meeting and preparing for future meetings |

| 12 | Review of program progress and goals | Review of program progress and goals |

| Boosters | Family updates and check-ins | Family Updates and check-ins |

Over the next four meetings, group members work towards changes in order to attain enhanced wellbeing, including engaging in pleasant family activities, more stable family routines, open communication, conflict resolution, and strengthening of the marital relationship. In meeting 10, a family meeting is conducted with individual families so they can achieve a new and shared understanding of depression and their family goals. Meetings 11 and 12 allow group members to process their family meeting in their separate groups, learn about how to plan more family meetings, and reflect on the growth of their families during the course of the program. Youth also create a video of their experiences in the program, which families view at a celebratory post-intervention meeting. Two monthly booster meetings include brief family meetings and reinforce the awareness and skills learned and problem solve any concerns that may have arisen since the program.

A Case Study of Fortalezas Familiares

Mariana’s initial depression scores were in the clinical range. During the first FF meetings, Joaquín described at length his confusion about and frustration with Mariana’s lack of interest in family life and persistent irritability. Psychoeducation and group process helped Mariana understand how her cognitions, emotions, and behaviors were connected, and how these were linked to her life story, but her engagement and commitment to change were low. In spite of other group members’ encouragement, Mariana refused to consider medication treatment.

It wasn’t until meeting 3 that Mariana discussed in great detail and with intense emotion her chronic history of trauma, poverty, and loss. She described her grief as God’s punishment for leaving her mother in Mexico. Although facilitators honored her belief, they explored how she could seek comfort in God for the adversity in her life. In addition, many group members reassured Mariana that God wouldn’t want to punish her, but rather for her to do well in her life as a way to honor her mother’s memory. Facilitators followed up on this suggested shift from her past to her present by connecting Mariana’s longing for her mother with her children’s longing for connection with her. Perspective-taking allowed Mariana to understand and commit to her family’s needs, and allowed Joaquín to become more empathetic of Mariana’s life story. Meanwhile in the youth group, Antonio was able to express confusion, concern, and guilt about his mother’s depression and the frequent arguments between his parents for the first time in meeting 3. He learned to identify and use positive coping skills during this time.

In meeting 4, focused on culture, Mariana and Joaquín shared their concerns about what they perceived to be Antonio’s rebellious behavior as he enters adolescence, and learned about acculturative risks on children in the United States. In the group they practiced conversations they can have as a family about discrimination and about remaining close in spite of diverging cultural expectations. After the family participated in the action-oriented activities, Antonio evidenced a new perspective on the sacrifices made by his parents to provide him with a better life than they had in Mexico. As families shared ways of remaining connected to their cultural traditions, for example, by participating in “posadas” (religious ritual) during the holidays, they learned about the value of these traditions in further strengthening family bonds.

During meetings 5 and 6, Mariana’s affect was visibly more positive than before and she became more engaged in group discussion and activities. For example, she and Joaquín became more planful about carrying out family activities and about supporting each other’s new strengths with their children. During meeting 6, Mariana and Joaquín disclosed to group members about Antonio’s biological father. In the youth meeting, Antonio spoke in more detail about his family’s difficulties. After learning about the family cycle, he was able to offer examples of ways that he could turn negative interactions with his family into positive ones. He reported spending more time with his parents and noticing improvement in his mother’s mood.

In spite of this progress, an argument between Mariana and her sister-in-law, in which the latter alleged to having an affair with Joaquín (to which she later confessed to be false), gave way to a setback in the family during the week of meeting 7. With great shame, Mariana told the group that while confronting Joaquín about her sister-in-law’s allegations, she pulled out a kitchen knife and threatened him in front of the children. Although no one was hurt, she felt deeply ashamed about her actions. Sobbing in front of the group, she apologized to Joaquín and reassured him that she has since then sought medication treatment. He also apologized to her for not paying enough attention to her needs. This situation prompted Mariana and Joaquín to commit to bringing back trust to their relationship and sparked conversations among others about their own vulnerable relationships. Mariana sought advice from the group as to how she could talk about this incident with her children. Concurrently, Antonio shared this story with the youth group, and he was able to relate those struggles directly back to how it was affecting him.

During meeting 8 about marital conflict resolution, Mariana and Joaquín updated the group on the events of the previous week. They both noticed improvement in the way they related to one another, and in turn, noticed that the children were more relaxed at home, which they also attributed to her improved mood. They learned other ways of feeling more connected as a couple. In the 8th youth meeting, Antonio shared his ideas about conflict resolution and was a group leader in offering examples in regards to using “I” statements to resolve conflict.

The family meeting two weeks later was highly successful. With reassurance and assistance from the facilitators and his parents, Antonio was able to ask Mariana about her depression and about the recent “knife” incident. Mariana managed her emotions well during this conversation, validated his concerns and learned that what Antonio feared the most was that she and Joaquín would divorce. Joaquín held her hand and reinforced her position as a parent during this conversation. They communicated to Antonio changes they are making to improve family life, such as her medication treatment and working on communication and family time together.

Over the final weeks of the program, Mariana, Joaquín, Antonio, and Amanda had two family meetings on their own that they described to be successful in helping the family feel connected and to set goals for the family. Mariana appeared radiant during the final meetings, as she paid more attention to her appearance and dress, and her affect was more positive. She and Joaquín evidenced a renewed understanding of their relationship vulnerabilities and strengths. Between the two booster meetings, Mariana and Joaquín had a family meeting with Antonio and they used the communication skills learned in the FF program to disclose the identity of Antonio’s biological father. Much to their surprise, Antonio remained calm and told them that he would always see Joaquín as his father, but that he was glad he knew. At the final youth booster meeting, Antonio reported feeling closer to his parents than he had ever felt to them before. He also reported that overall his family was able to communicate better, resolve conflict quicker and in a calmer manner, and was spending more quality time together. At the post-assessment and up to a final, 8-month follow-up, Mariana’s depression scores fell below the clinical range, and the family reported improvements in their communication, routines, and cohesion. The family maintained regular contact with the other participating families.

Summary of Program Outcomes

We conducted a pilot study of the FF program with 16 adult female clients with a major depressive disorder and their families. Thirteen families were from Mexico and three were from Central and South America. Of the 16 participating families, 13 completed the program (81%), including 13 mothers, 9 fathers, 1 grandmother, and 18 adolescents. Participants completed pre-and post-intervention measures about parent and child coping and mental health, family functioning, and acculturative stressors. All mothers experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms from pre-test to post-test. Further, four mothers scored in the clinical range on a measure of psychological symptoms at pre-test, and only one mother, whose husband did not participate in the program due to substance abuse issues, remained in the clinical range at post-test. This mother was offered referrals and she continued to meet with her clinician. Caregivers also reported lower levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms at post-test, and one father who had scored in the clinical range at pre-test, no longer did at post. Parents and caregivers reported improvement in youth internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and youth reported increased use of positive coping strategies. Mothers and caregivers reported a significant increase in social support and improvement in family functioning (i.e., routines, communication, cohesion, parenting skills) were reported by all participants. Measures were selected for their wide use with Latinos, availability in Spanish, and adequate psychometric properties. Detailed information about the study measures and outcome data, including an 8-month follow-up, as well as qualitative data from interviews and focus groups are presented elsewhere (Author et al. 2012).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Sociocultural and family processes shaping immigrant Latino families’ adjustment in the context of maternal depression, need to be understood to address risk and promote resilience among children. A developmental psychopathology framework was useful in understanding the dynamic interplay between family and sociocultural risk and resilience processes. However, sociocultural processes have been largely understudied, even in the developmental psychopathology literature (Cicchetti & Toth 2008). Our work shows that a deeper understanding of how sociocultural processes, such as acculturative stress and cultural values, shape family relational patterns and personal adjustment, and can serve as a foundation for the development of clinically effective and culturally acceptable interventions.

A family systems framework was useful in addressing relational patterns within the family. Families’ understanding of their relational patterns was critical to their engagement in the program, as many mothers with depression believed until that point that they were able to “hide” their symptoms and not affect the family. Similarly, many spouses and children until that point lacked adequate understanding of how these symptoms were connected to other changes in the family. Later in the program, individual family meetings were powerful because the family came together for the first time to listen to and address each other’s concerns in a supportive environment. Increased understanding and competence was likely conducive to a positive marital relationship, stronger coparenting, warmer and more consistent parent-child interactions, and stable family activities and routines, all of which, have been associated with wellbeing in Latino families (Sotomayor-Peterson, Figueredo, Christensen, & Taylor, 2012). Perhaps the significant changes in family functioning noted after the family meetings suggest the need to anchor the intervention more in a family systems framework, relative to our other frameworks. Although our family meetings were successful in part because family members had their own space in their previous meetings to grieve losses, understand and reframe their family patterns, and learn new skills to improve family life, in future implementations of FF we will consider the value of incorporating more family meetings earlier in the program.

The FF program addressed the general risk and protective mechanisms that shape children’s outcomes when a mother has depression, accounting for specific sociocultural processes that are salient to Latino immigrant families. In FF, we discussed immigration history and losses, acculturative adjustment of parents and children, and experiences of discrimination and other social challenges often common in this population. There were also many protective factors among these families that were incorporated, such as cultural traditions (e.g., family rituals and religious traditions) for bonding the family, family cohesion and interdependence, large extended family networks to increase support, and optimism for the future, among others.

In addition to using culturally and socially congruent examples and concepts, we relied on action-oriented techniques (e.g., acting) to facilitate family engagement and perspective-taking between parents and youth. Moreover, the program infused greater focus on marital relationships given that the majority of women in the program had a spouse/partner who also participated. These program modifications, the linguistic customization of the program, and attention to the facilitators’ language and culture, were found to increase the family’s acceptability of the program.

To the best of our knowledge, the FF program is the only intervention for Latino families facing maternal depression that involves the full and equal participation of mothers, caregivers, and all pre-adolescent and adolescent children in each meeting. Young children also participate in programmatic activities as part of a childcare group. By including the whole family, fathers—who are typically a difficult group to engage— become more involved in the program and in the family’s recovery, potentially amplifying the effects of the program. Thus, the design, feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes of the FF program suggest that it is meeting the needs of Latino immigrant families when a mother has depression. The efficacy of the FF program needs to be ascertained and we are currently planning to evaluate it using a randomized design.

The FF program targets Latino families with pre-adolescent and adolescent children but the program may have greater impact with younger children, who have yet to experience dissonant acculturative stressors. A few of the parents reported being monolingual in Spanish, and their adolescent children, in contrast, had very low levels of Spanish fluency. Thus, reaching families prior to the marked acculturative parent-child dissonance that is more common in adolescence could potentially strengthen family outcomes and children’s coping with family and community stressors. We are currently working to develop a program for children ages 4 to 8 to accompany the youth and parent/caregiver groups.

Research and social policy play an important role in making family programs more effective and accessible to immigrant families. Policymakers need to recognize the role of family and sociocultural contexts in the health and illness of individuals (Doherty, 2002). When a mother experiences depression, the cost to the children can be significant. And when the family faces poverty, discrimination, and restrictive immigration policy, as in the case of many immigrant families, recovering from and coping with the illness and its associated family relational patterns may be even more difficult. Thus, professionals are charged to offer effective and culturally congruent interventions that can address the family processes and sociocultural risks and strengths of Latino immigrant families.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Quintana for reviewing earlier drafts of this article.

The project described was supported by the University of Wisconsin Morgridge Center for Public Service; and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

All names and some details have been changed to protect the identities of the individuals

References

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: Evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112:119–113. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR. When a parent is depressed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Cardoso J, Thompson SJ. Common themes of resilience among Latino immigrant families: A systematic review of the literature. Families in Society. 2010;91:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:317–327. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch KR, Bohon SA, Kim HK. Adaptation among immigrant families: Resources and barriers. In: Price SJ, Price CA, McKenry PC, editors. Families and change. 4. Los Angeles: Sage; 2010. pp. 285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, Kim S, Pinedo TM, Miller IW. Developing a culturally appropriate depression prevention program: The Family Coping Skills program. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:99–112. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman MV, Perreira MV. The well being of immigrant Latino youth: A framework to inform practice. Families in society. 2005;86:104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescent depression. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2008. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Corona R, Lefkowitz ES, Sigman M, Romo LF. Latino adolescent’s adjustment, maternal depressive symptoms, and the mother-child relationship. Family Relations. 2005;54:386–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crean HF. Conflict in the Latino parent-youth dyad: The role of emotional support from the opposite parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:484–493. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo EJ, Llerena-Quinn R, Shapiro R, Colon F, Rodriguez P, Gallagher K, Beardslee WR. Adaptation of the Preventive Intervention Program for depression for use with predominantly low-income Latino families. Family Process. 2009;48:269–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ. Can a family-focused approach benefit health care? In: Bogenschneider K, editor. Family policy matters. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Immigrant family processes. In: Walsh F, editor. Normal family processes. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 280–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heilemann MV, Coffey-Love M, Frutos L. Perceived reasons for depression among low income women of Mexican descent. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2004;18:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imber-Black E, Roberts J. Rituals for our times: Celebrating, healing, and changing our lives and our relationships. Northvale, N. J: J. Aronson, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Kuperminc G, Perilla J, Murphy A, Ibañez G, Casey S. Ecological and ethical perspectives on filial responsibility: Implications for primary prevention with immigrant Latino adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25:81–104. doi: 10.1023/B:JOPP.0000039940.99463.eb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parra Cardona JR, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, Bernal G. Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for Latino immigrants: The need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Family Process. 2012;51:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plano R, Zayas LH, Busch-Rossnagel NA. Mental health factors and teaching behaviors among low-income Hispanic mothers. Families in Society. 1997;78:4–12. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: A portrait. 3. Berkely, CA: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Szapocznik J, Maldonado-Molina MM, Schwartz SJ, Pantin H. Drug use/abuse prevalence, etiology, prevention, and treatment in Hispanic adolescents: A cultural perspective. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FI, Guarnaccia PJ, Mulvaney-Day N, Lin JY, Torres M, Alegria M. Family cohesion and its relationship to psychological distress among Latino groups. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:357–380. doi: 10.1177/0739986308318713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento IA, Cardemil EV. Family functioning and depression in low-income Latino couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2009;35:432–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao M. Becoming bicultural: Risk, resilience, and Latino youth. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor-Peterson M, Figueredo AJ, Christensen DH, Taylor AR. Couples’ cultural values, shared parenting, and family emotional climate within Mexican American families. Family Process. 2012;51:218–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Cronkite RC, Swindle R, Robinson RL, Sutkowi A, Moos RH. Parental depression as a moderator of secondary deficits of depression in adult offspring. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2009;40:575–588. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of Depressed Parents: 20 Years Later. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Lester RJ, Cabassa LJ, Fortuna LR. Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:275–287. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]