Abstract

Targeting sequencing to genes involved in key environmental processes, i.e., ecofunctional genes, provides an opportunity to sample nature's gene guilds to greater depth and help link community structure to process-level outcomes. Vastly different approaches have been implemented for sequence processing and, ultimately, for taxonomic placement of these gene reads. The overall quality of next generation sequence analysis of functional genes is dependent on multiple steps and assumptions of unknown diversity. To illustrate current issues surrounding amplicon read processing we provide examples for three ecofunctional gene groups. A combination of in silico, environmental and cultured strain sequences was used to test new primers targeting the dioxin and dibenzofuran degrading genes dxnA1, dbfA1, and carAa. The majority of obtained environmental sequences were classified into novel sequence clusters, illustrating the discovery value of the approach. For the nitrite reductase step in denitrification, the well-known nirK primers exhibited deficiencies in reference database coverage, illustrating the need to refine primer-binding sites and/or to design multiple primers, while nirS primers exhibited bias against five phyla. Amino acid-based OTU clustering of these two N-cycle genes from soil samples yielded only 114 unique nirK and 45 unique nirS genus-level groupings, likely a reflection of constricted primer coverage. Finally, supervised and non-supervised OTU analysis methods were compared using the nifH gene of nitrogen fixation, with generally similar outcomes, but the clustering (non-supervised) method yielded higher diversity estimates and stronger site-based differences. High throughput amplicon sequencing can provide inexpensive and rapid access to nature's related sequences by circumventing the culturing barrier, but each unique gene requires individual considerations in terms of primer design and sequence processing and classification.

Keywords: functional genes, nifH, aromatic hydrocarbon, nirS, primer specificity, clustering analysis, nirK, nitrogen cycling

Introduction

Microbial community composition is most frequently assessed using the 16S rRNA gene marker, either in direct-targeted amplification or seed-based retrieval from metagenomic datasets. However, the linkages between phylogeny and a particular biological function is weak at best. The targeted sequencing of functional genes provides information that directly codes for function and hence provides a functional framework for classification, and by inference, its host's taxonomic identity, at a depth that is not currently attainable with metagenomic libraries. Varying strategies for processing these data have been employed, mainly based on nucleotide sequences. In many cases processed nucleotide sequences are subjected to BLASTn analyses against the non-redundant NCBI database with or without prior clustering. Translated protein sequences have the advantage of more accurately reflecting biological function and thus dissimilarity cutoffs can be more informative than those based on DNA.

Reference database composition significantly influences overall diversity estimates. This is complicated by the inclusion of non-curated sequences whose true biological function is highly uncertain. Bioinformatic approaches, such as Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM) of functional genes based on seed sequences, can be used to mine larger databases for relevant implied gene function. However, there remains uncertainty as to the appropriate filtering cutoffs, as this varies widely among functional genes. Additionally, many issues are implicitly related to initial primer design, which affect both coverage and specificity (Iwai et al., 2011a).

Downstream sequence processing also poses a challenge in the analysis of both community composition and overall diversity. Particularly, the choice of cluster dissimilarity cutoff values and the use of DNA or amino acid sequences as the basis for analysis are especially variable in the literature (Heylen et al., 2006; Palmer and Horn, 2012). Translated sequences better reflect function through residue conservation at key enzymatic sites, and thus protein-based clustering would be expected to better indicate functional relatedness. Lastly, evidence of horizontal gene transfer of these genes and the resulting impact on diversity indices is still largely unknown (Hirsch et al., 1995; Boucher et al., 2003; Heylen et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2008) and warrants attention as more sequences become publicly available.

Different analysis steps are illustrated below for four different ecofunctional genes, i.e., genes that directly code for a protein catalyzing an important ecological process. These steps are particularly important since a common “pipeline” does not exist and would probably not be appropriate for all ecofunctional genes. The output of any pipeline is improved through careful attention at each stage, taking database coverage and unknown genetic diversity into account. For example, the reference databases for the three ecofuncional groups are of different sizes (dioxin-lke aromatic hydrocarbon degradation < denitrification < nitrogen fixation). For the first gene family example, new primers that target the ether-linked, aromatic hydrocarbon degrading genes dxnA1, carAa, and dbfA1, are evaluated to determine primer specificity using a combination of in silico, environmental and cultured strain sequences. Next, primer coverage and downstream processing, particularly in regard to choice of clustering dissimilarity cutoffs, are illustrated for the nitrite reductases in denitrification. Lastly, the N-fixing gene nifH is used as the example for analyzing differences obtained using both supervised and non-supervised OTU generation.

Aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading dxnA, dbfA1, and carAa genes

Aromatic hydrocarbons comprise a chemically diverse class of organic compounds that include monoaromatics (e.g., benzene, benzoate), bicyclic (biphenyls,) polycyclic aromatics (e.g., phenanthrene), N-containing heterocyclics (e.g., carbazole) and oxygen-linked polyaromatics (e.g., dibenzofuran, and dibenzo-p-dioxin). Of these, certain chlorinated dioxins are the most problematic due to their persistence and carcinogenicity, requiring the remediation of contaminated soils and sediments. Potential chemical remediation schemes to detoxify dioxin contaminated soils are costly (Kulkarni et al., 2008). Microbial degradation of dioxins has been studied as an alternative method, but evidence of biodegradation is very limited, plus there are few isolated microbes capable of their degradation. Gene-targeted amplicon sequencing is an alternative to culturing isolates to identify novel catalytic biodiversity, as was done with biphenyl dioxygenase (Iwai et al., 2010). Hence, we used gene-targeted amplification and sequencing to characterize dioxygenases with activity toward problematic dioxin chemicals. Three dioxygenases that attack the angular ether linkages in these molecules are known to catalyze the first step of the dioxin degradation pathway: dioxin dioxygenase (dxnA1), dibenzofuran dioxygenase (dbfA1 or dfdA1), and carbazole dioxygenase (carAa) (Field and Sierra-Alvarez, 2008). A number of PCR primers are reported that can be used to probe samples for aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase genes (ARDHs) (Iwai et al., 2011b), including a quantitative PCR primer specific to the dxnA1 in Sphingomonas wittichii str. RW1, which is the only well-characterized dioxin degrader (Hartmann et al., 2012). However, no previously published primer set meeting the requirements for amplicon sequencing solely targets dioxygenases active toward dioxins (Iwai et al., 2011b).

Reference sequence database generation

In order to identify reliable reference sequences with known activity toward dioxins, dioxygenase sequences were obtained through a manual search of the GenBank database (keywords included angular, dioxin, dibenzofuran carbazole and dioxygenase). Amino acid similarity of the harvested sequences (Table A1) showed three groups within the superfamily of Rieske dioxygenases: Group 1, dioxin 1,10a dioxygenase (dxnA1) and dibenzofuran 4,4a dioxygenase (dfdA1); group 2, dibenzofuran 4,4a dioxygenase (dbfA1); group 3, carbazole 1,9a dioxygenase (carAa). To harvest additional related sequences, the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank non-redundant protein database was searched using Hidden–Markov Models built from all reference sequences from each group with HMMER (Eddy, 2009). These results were obtained from the December 2010 release of FunGene (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu, see also Fish et al., 2013). An HMM bits saved score cutoff of 700 was used, and no additional sequences were obtained through this search, which reinforces the low number of sequenced (or cultured) strains with activity toward dibenzo-p-dioxin. Specific degenerate primers were designed from amino acid consensus regions (Table A2) and specificity was determined experimentally by PCR using all indicated strain DNA as template with all three primer sets. The primers were specific to only the gene cluster for which they were designed and did not produce amplicons from closely neighboring gene clusters except in the case of the dbfA1 primer set which produced a minor amplification product when Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 was the template DNA (Table A1).

Amplification and sequence processing

Two environmental samples were chosen as template DNA to be used in gene-targeted metagenomics: a well characterized polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)-contaminated rhizosphere soil (Leigh et al., 2007), and a pristine Kansas prairie soil (KS) (Williams et al., 2011), from the Konza Prairie (39°05′N, 96°35′W). Both of these soils should contain polyaromatic hydrocarbons from plant secondary metabolites. The former contains PCBs and likely low levels of dioxins or other angular ether structures due to industrial activity, and the latter could have been exposed to polyaromatic ethers from natural prairie fires. The PCR primers used in this study were synthesized with sequencing adapters and 8 base oligo multiplex sequencing barcodes. PCR products were prepared as described previously (Iwai et al., 2010) and pooled with other samples for pyrosequencing (Roche 454 GSFLX Titanium Sequencer).

Raw reads were filtered through barcode matching and quality filtered using the Ribosomal Database Project II (RDP-II) Pyro Initial Process tool (Cole et al., 2009) using a forward primer maximum mismatch of 2 and minimum length of 300 bp. Reads passing the initial filters were aligned and frameshift corrected and translated into protein sequences using the RDP FrameBot tool [http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/FunGenePipeline/, see also Wang et al., 2013)]. A FrameBot reference set was obtained using manual selection for a broad diversity of aromatic (including dioxin, dibenzofuran, carbazole, biphenyl, PAH, phenylpropionate, etc.) hydroxylating dioxygenase genes from the FunGene repository with an HMM bits saved score cutoff of 350. Protein reads with a length >100 amino acids and ≥30% identity to the nearest reference sequence were used for further analysis (Table 1). UCHIME v4.2.40 using the de novo mode was used to determine chimeric sequences. These quality filtered protein sequences and corresponding reference amino acid sequences were aligned by HMMER and trimmed. The obtained sequences were combined with reference sequences and were clustered at 50% dissimilarity, using the RDP mcClust tool (Cole et al., 2009). This clustering method was selected because there are so few known strains with activity toward dioxins. Clusters not containing a reference sequence were considered novel clusters (Iwai et al., 2010). The 50% dissimilarity cutoff was chosen as this approximate distance is where reference sequences were clustered to determine primer design groups. One representative sequence from each cluster was selected using the representative sequence tool on the RDP FunGene pipeline. These sequences were used to construct a nearest neighbor-joining tree using MEGA 5.1 software. No amplification products were obtained using the dbfA1 primer set. Also eight dxnA1/dfdA1 sequences were classified as chimeras by UCHIME; however, they were singleton sequences that were not considered in downstream analyses. Sequences were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive under accession numbers ERS329748-ERS329751 and ERS329770-ERS329772.

Table 1.

Obtained sequences statistics.

| Primer set | Sample name | Match barcode | Passed initial processing | Contains frame-shift | Passed Frame-Bot | Avg. length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dxnA1/dfdA1 | Rhizosphere | 2,319 | 2,095 | 456 | 641 | 389 |

| KS | 2,844 | 2,521 | 451 | 690 | 375 | |

| Environmental sample total | 5,163 | 4,616 | 907 | 1,331 | ||

| MC | 1,247 | 1,204 | 626 | 1,204 | 450 | |

| carAa | Rhizosphere | 720 | 543 | 128 | 193 | 460 |

| KS | 673 | 594 | 194 | 339 | 465 | |

| Environmental sample total | 1,393 | 1,137 | 322 | 532 | ||

| MC | 612 | 501 | 340 | 500 | 476 |

A mock community (MC) was composed of the strains used in validation of primer specificity and yielded the correct sequences and are not described further.

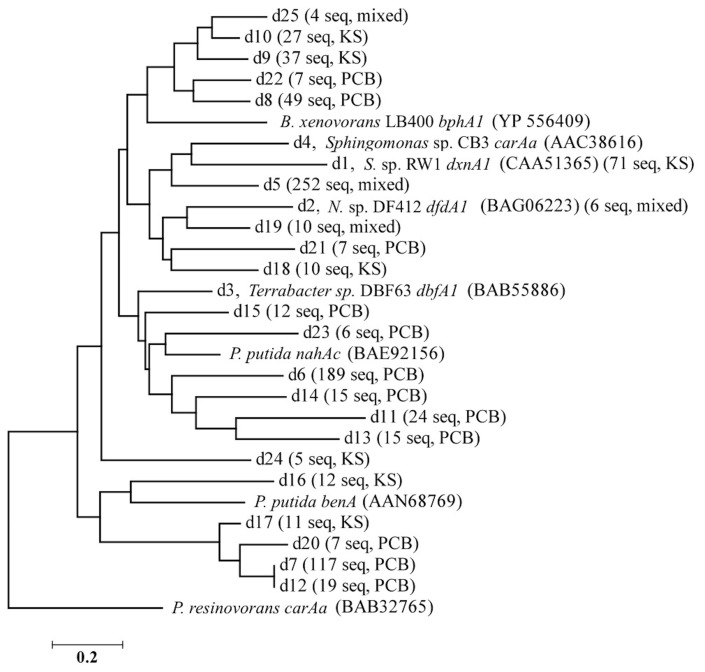

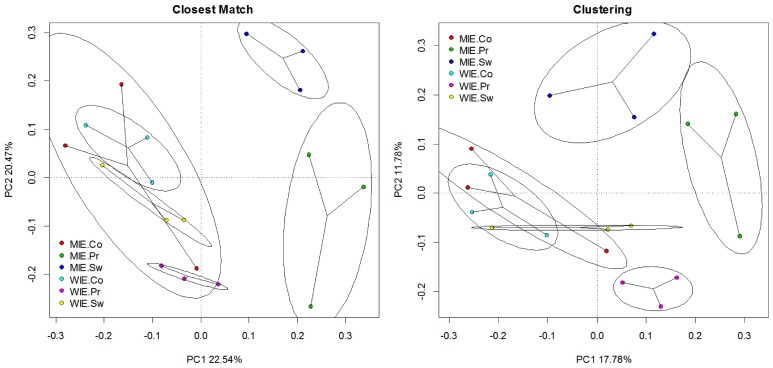

The 1,863 obtained sequences revealed the in situ diversity of dioxygenases with suspected activity toward dioxins (Figure 1). The majority of dxnA1/dfdA1 sequences formed novel clusters (Figure 1A). Many clusters were shared in both the KS soil and the PCB soil. However, the dominant dxnA1/dfdA1 clusters differ between sites. Two clusters (clusters d1, d5) comprise 68% of sequences in the KS sample while these same clusters only represent 4% of the PCB soil sequences. Notably, cluster d1 contains the reference sequence from the (chloro)dioxin oxidizing Sphingomonas wittichii str. RW1 and represents nearly 10% of the KS soil obtained dioxygenase gene community. This indicates that genes similar to this important dioxygenase are present in this prairie soil. The PCB sample was dominated (49% of sequences) by two clusters, d6 and d7, which represent only 1% of the KS sequences. These data show site-specific populations having novel dioxygenases. The specificity of the primer sets was re-affirmed as reference sequences used to design the dbfA1 primer set did not cluster with any of the obtained sequences using the dxnA1/dfdA1 primer set at 50% dissimilarity. Similarly, many of the obtained sequences, including the most abundant novel cluster, formed a clade on the same branch as dxnA1 and dfdA1 (Figure 2). Other sequences were more distantly related to this clade, which may denote differing dioxygenase specificities. While a majority of carAa sequences clustered with reference sequences at 50% dissimilarity (Figure 1B, cluster c1), similar ecological trends, including site-specific populations, were also observed within the carAa sequences. The carAa obtained sequences cluster separately from the reference sequences at 70% similarity cutoff.

Figure 1.

Results of clustering obtained sequences with the reference sequences. (A) Results using the dxnA1/dfdA1 primer set. (B) Results using the carAa primer set. Clusters are only shown that contained at least four sequences. There were an additional 12 clusters that contained two or three sequences.

Figure 2.

Nearest neighbor-joining tree of the representative sequences of each dxnA1 cluster shown in Figure 1. Branch names designate: cluster name (from Figure 1), name and accession number of reference sequence in that cluster (if applicable), number of obtained sequences from pyrosequencing, and the predominate sample from which the sequences originated. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE, trimmed to a common region for all sequences, and the tree was made using MEGA 5.1. N. sp. DF412 refers to Nocardioides sp. DF412.

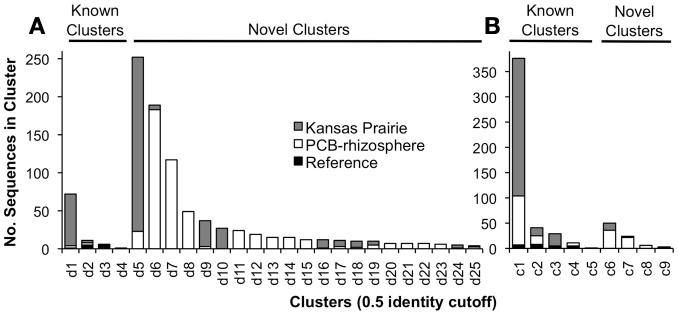

Sequence conservation

A consensus amino acid sequence based on the obtained sequences was compared to an aligned consensus sequence of reference (GenBank) sequences. When we searched for conserved amino acids, a known iron-binding motif (DX2HX3−4H (Nojiri et al., 2005), where X is any given amino acid) was observed in >95% of sequences of both dxnA1/dfdA1 and carAa obtained sequences (Figure 3). In addition, another conserved motif (>95%), NWK or NWR, was observed. Although no associated function could be found in the literature regarding a role of the highly conserved NW(K/R) motif including a search of the characterized carAa protein structure (Nojiri et al., 2005), the motif appears essential to the protein. It is possible that the NW(R/K) motif plays a role in positioning of the substrate binding amino acid at the active site of the protein. In the case of carAa, Gly-178 is implicated to hydrogen bond to carbazole and the NWR motif is situated on the same alpha helix as Gly-178 (Nojiri et al., 2005). The identity of the third amino acid of this motif is specific to each group.

Figure 3.

Percent conservation of translated obtained nucleotide sequences to protein sequences. (A) Results using the dxnA1/dfdA1 primer set. (B) Results using the carAa primer set. Key conserved amino acid positions are indicated. The DX2HX3−4H iron-binding site is indicated as well as the uncharacterized, yet highly conserved NW(K/R) motif. The asterisk (*) indicates positions for which obtained sequences were conserved at a higher rate than reference sequences.

While some recent advancements have been made in dioxin degradation with previously isolated strains, especially S. wittichii str. RW1 (Nam et al., 2006), progress in isolating novel degrading strains has been slow for several decades (Field and Sierra-Alvarez, 2008). In the neighboring biphenyl dioxygenase clade, despite having many more degrader strains isolated, gene-targeted metagenomics still revealed extensive novel diversity (Iwai et al., 2010). For dioxin clades, amplicon pyrosequencing revealed novel dioxygenase sequence clusters of intermediate sequence similarity between the dxnA1 and dfdA1 genotypes. This reveals a likely continuum of genetic diversity between these two distinct but functionally similar groups. According to obtained dioxygenase sequences, the majority of potential dioxin degraders in these communities have no cultured representative, and their diversity, in terms of cluster abundance, far exceeds that of known degraders, as was previously found for bphA1 (Iwai et al., 2010).

nirS and nirK primer coverage and clustering

Denitrifiers are an important functional group in the nitrogen (N) cycle and N-cycle functional genes have been targeted for diversity, abundance and expression studies (Braker et al., 2000; Prieme et al., 2002; Philippot et al., 2007; Palmer and Horn, 2012). However, primer coverage poses a continuing problem in the amplification and sequencing of N cycle functional genes in environmental samples. The majority of the current primers are based on the alignment of relatively few reference genes and tested on a relatively small number of type strains. For example, the majority of nirK primers are based on class I CuNIR genes from α-proteobacteria (Braker et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2008) and do not amplify class II and III nirK sequences (Green et al., 2010), which include the archaeal nirK (Treusch et al., 2005; Bartossek et al., 2010). Overall, few have investigated coverage of these primers in-silico (Throbäck et al., 2004; Heylen et al., 2006; Green et al., 2010) with comparison to environmental datasets. Current nirS and nirK primer limitations are thus due, in part, to the limited number of functional gene sequences from cultivated and identified denitrifiers (Heylen et al., 2006), high sequence divergence at current primer sites (Green et al., 2010), and the availability of but a few deep sequencing studies (Palmer et al., 2012; Palmer and Horn, 2012) that can be used to gauge primer performance in environmental matrices.

Initial sequence processing

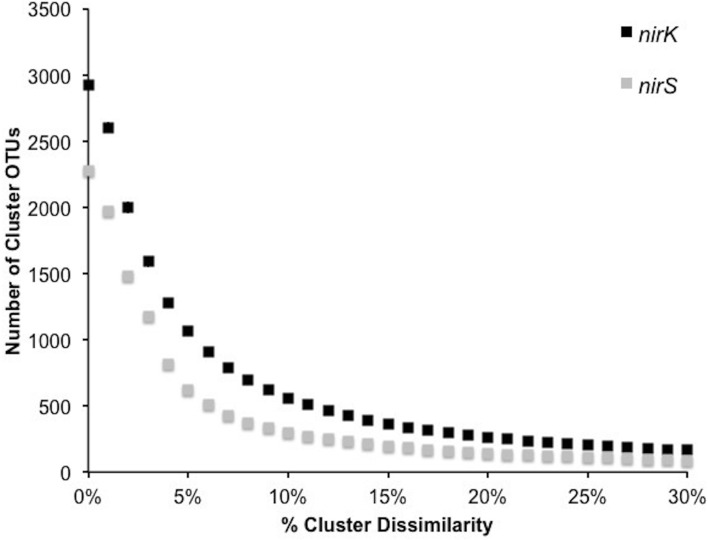

In order to investigate the diversity of denitrifiers and test primer coverage in environmental samples nirK was amplified using primers nirK517F/1055R (Chen et al., 2010) and nirS with cd3af (Michotey et al., 2000) and R3cd (Throbäck et al., 2004) with 9 bp tag sequences using DNA extracted from six tallgrass prairie sites (34°58′54″N, 97°31′14″W) using freeze-grinding mechanical lysis (Zhou et al., 1996). Sequences were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive under accession numbers ERS329737-ERS329747. Raw sequences were processed through the RDP pyrosequencing pipeline and the ~540 and ~425 bp amplicons yielded sequences averaging 456±45 bp (nirK) and 383±36 bp (nirS). Since the forward and reverse reads overlapped each other, both directions were analyzed together (Palmer and Horn, 2012; Palmer et al., 2012). Translation and frameshift correction were performed using the RDP FrameBot tool. The average number of frameshifts per gene was nearly identical (nirK 1.0 ± 1.3, nirS 0.6 ± 1.0) with the model alignment covering the full amplicon length. Complete linkage clustering on 3,400 randomly resampled aligned protein sequences from six replicates per gene revealed an inflection point of approximately 5–8%, reflecting a change from intra- to inter-species sequence homology (Figure 4). A 5% protein-protein dissimilarity was chosen for both genes for downstream analyses. This is in contrast to previous studies where nirK and nirS were clustered at 4% nucleotide dissimilarity (Chen et al., 2010) or nirK at 17% and nirS at 18% (Palmer et al., 2012; Palmer and Horn, 2012). A mean amino acid dissimilarity of 5% of genes in common in genomes corresponds to the 70% DNA-DNA hybridization that is currently the definition of bacterial species. Hence a 5% clustering cutoff approximates species level differences (Cole et al., 2010).

Figure 4.

Number of OTUs generated by complete linkage clustering of aligned protein sequences for nirK and nirS from 0 to 30% dissimilarity.

nirK reference dataset and primer coverage

For nirK, 523 sequences from the RDP FunGene database were chosen as a BLASTp reference database using 50% minimum HMM coverage and 100 minimum score filters followed by further database refinement. This included 69 sequences linked to unclassified taxa and 114 linked to unique genera comprising 215 unique species. Blastp of the 1,068 representative cluster sequences at 5% protein-protein dissimilarity yielded only 52 unique closest-match species comprising 20 classified genera (Table 2). Previously, with a pyrosequencing depth of 11,612 sequences, nirK was assigned to 9–10 species-level OTUs in palsa peat and permafrost soil samples using a 17% dissimilarity threshold (Palmer and Horn, 2012; Palmer et al., 2012).

Table 2.

Closest BLASTp hits for nirK cluster representative sequences at the genus level with the average BLASTp identity with standard errors and the range of percent identities for each genus.

| Genus | Avg % ID | % ID Range |

|---|---|---|

| Achromobacter | 81.5 ± 0.3 | 42.1 – 100 |

| Afipia | 83.4 ± 0.3 | 71.9 – 94.0 |

| Alcaligenes | 77.3 ± 0.4 | 67.1 – 86.1 |

| Bradyrhizobium | 82.6 ± 0.2 | 56.5 – 99.4 |

| Chelativorans | 81.1 ± 1.2 | 66.1 – 88.9 |

| Maritimibacter | 73.4 ± 2.2 | 68.9 – 75.8 |

| Mesorhizobium | 79.8 ± 0.2 | 62.1 – 100 |

| Methylocystis | 84.7 ± 1.2 | 80.6 – 90.4 |

| Nitratireductor | 82.8 ± 0.3 | 65.8 – 97.3 |

| Nitrosomonas | 70.3 | n.d. |

| Ochrobactrum | 92.8 ± 0.4 | 69.1 – 97.7 |

| Phaeobacter | 71.9 | n.d. |

| Pseudomonas | 87.6 ± 2.6 | 79.0 – 97.7 |

| Rhizobium | 85.6 ± 2.1 | 75.3 – 95.7 |

| Rhodopseudomonas | 80.6 ± 0.1 | 49.5 – 92.2 |

| Roseovarius | 67.1 | n.d. |

| Shewanella | 73.2 ± 1.4 | 68.2 – 76.3 |

| Sinorhizobium | 88.4 ± 1.4 | 70.4 – 99.4 |

| Starkeya | 87.2 ± 3.2 | 68.4 – 93.6 |

| Uncultured bacteria | 82.5 ± 1.0 | 52.9 – 98.8 |

In order to understand this low retrieved nirK diversity, we analyzed the role of primer coverage by using the updated nirK reference database with RDP probe match. The nirK517F primer was specific for 96 strains comprising 39 species, 145 with 1 mismatch, and 188 with 2 mismatches while nirK1055R was specific for 46 strains composed of 17 species, 104 with 1 mismatch and 121 with 2 mismatches. Other frequently used nirK primers such as F1aCu/R3Cu (Throbäck et al., 2004) and nirK1F/nirK5R (Braker et al., 1998) were also evaluated (Table A3). All primers preferentially targeted the α-Proteobacteria, although captured diversity will likely be limited by reverse primer sequence homology when invoking strict PCR conditions. This issue was not evident in our results. Only the Achromobacter and Alcaligenes were captured with 0 mismatches, leaving 14 genera in the β-Proteobacteria. Likewise, only the Pseudomonas and Shewanella denitrificans of the 23 γ-Proteobacteria reference genera were hit. The remaining 83 species from the class II and III Archaea, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi-Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were not targeted by any primer. Overall, primer coverage of the reference dataset was extremely low, resulting in a constrained diversity that re-affirms an urgent need for further exploration of nirK primer design, perhaps to other primer-binding regions (Green et al., 2010).

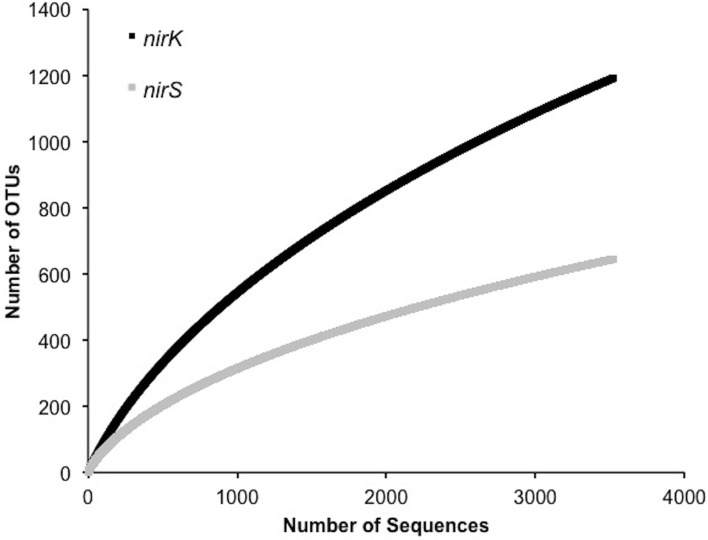

nirS clustering and primer coverage

A significantly lower number of classified, non-environmental sequences are available for nirS. Using a minimum HMM coverage of 50 and score of 600, a total of 109 nirS reference sequences comprising 45 unique genera and 63 species were obtained from the FunGene database for both taxonomic assignment and primer analyses. BLASTp of the 617 representative sequences at 5% protein-protein dissimilarity yielded 18 unique clusters linked to classified genera comprising 24 unique species and 3 unclassified bacteria (Table 3). Previously, 14 OTUs of nirS were retrieved from 918 sequences using an 18% nucleotide dissimilarity (Palmer and Horn, 2012). Overall, nirS total diversity was more constrained than nirK, as indicated by rarefaction curves (Figure 5). Average identity to the reference database was lower for nirS (76.5 ± 0.2%) than for nirK (81.7 ± 0.1%), similar to the lower nucleotide identity of nirS (74.7%) to the GenBank database than nirK (90.7%) in a previous study (Chen et al., 2010).

Table 3.

Closest BLASTp hits for nirS cluster representative sequences at the genus level with the average BLASTp identity with standard errors and the range of percent identities for each genus.

| Genus | Avg % ID | % ID Range |

|---|---|---|

| Aromatoleum | 74.3 ± 0.5 | 73.9 – 74.8 |

| Azoarcus | 72.4 ± 0.9 | 70.8 – 73.7 |

| Brachymonas | 73.4 ± 3.8 | 65.9 – 77.9 |

| Cupriavidus | 78.1 ± 0.3 | 67.2 – 99.2 |

| Dechloromonas | 96.6 ± 0.0 | 96.6 – 96.6 |

| Dinoroseobacter | 75.3 ± 2.8 | 72.3 – 80.9 |

| Kangiella | 72.0 ± 0.2 | 70.3 – 73.9 |

| Magnetospirillum | 77.0 ± 0.9 | 70.2 – 90.2 |

| Marinobacter | 71.0 ± n.d. | n.d. |

| Polymorphum | 69.5 ± n.d. | n.d. |

| Pseudogulbenkiania | 68.7 ± n.d | n.d. |

| Pseudomonas | 76.8 ± 0.7 | 68.9 – 93.1 |

| Ralstonia | 76.5 ± 0.1 | 72.7 – 80.0 |

| Rubrivivax | 83.2 ± n.d. | n.d. |

| Ruegeria | 73.3 ± 0.7 | 69.1 – 77.5 |

| Sideroxydans | 80.5 ± 1.1 | 79.4 – 81.7 |

| Stappia | 74.2 ± 0.7 | 69.9 – 76.9 |

| Thiobacillus | 72.2 ± 0.5 | 68.9 – 75.4 |

| Uncultured bacteria | 76.6 ± 0.3 | 68.0 – 94.4 |

Figure 5.

Rarefaction curves for 5% OTU dissimilarity for nirK and nirS.

For the primer analyses, primer cd3af hit 62 strains comprising 28 unique species with 0 mismatches, 73 with 1 and 89 with 2 mismatches within the reference dataset. Primer R3cd hit 48 strains comprising 27 unique species with 0, 67 strains with 1 and 98 with 2 mismatches. Another primer set (nirS1F/nirS6R; Braker et al., 1998) was also evaluated (Table A4). Primers nirS1F/nirS6R exhibited better coverage of the α-Proteobacteria while both were comparable in the β- and γ-Proteobacteria taxa. Neither performed well in targeting the Chloroflexi, Deinococcus-Thermus, Aquificales or Bacteroidetes. In both instances coverage was highly dependent on PCR stringency, with near full coverage of the β-Proteobacteria at 2 primer mismatches. Unlike nirK, refinement through degeneracy of the current primer sets should allow for higher coverage, although the current sequence availability from classified strains remains low.

nifH sequences processed using supervised and non-supervised methods

When pyrosequencing data are used to compare gene profiles or gene diversities among samples, it is necessary to first bin the sequences by one of two general methods. Either sequences can be clustered into OTUs at a specified distance (the unsupervised method) or sequences may be classified directly using a reference database [the supervised method, as in Wang et al. (2013)]. The choice of method depends on the specific goals and, to some extent, the current knowledge of the target gene. Clustering better preserves information on diversity and better enables the discovery of novel gene sequences while the supervised method yields more immediately interpretable results and better enables comparisons between different experiments. It is expected to fail, however, in instances where the reference database captures little of the existing gene diversity.

To contrast the performance of the supervised and unsupervised methods, soil samples were chosen from an investigation of various cropping systems on microbial soil diversity. These samples came from soils under corn, switchgrass and prairie species and represent the range of soil types in central to southern Michigan and Wisconsin. NifH sequence libraries were produced from DNA extracted from these soil samples by PCR per the protocol described by Wang et al. (2013) and analyzed for differences in gene diversities and gene profiles after binning sequences by each method.

Primer design is critical to capturing diversity of any gene (Iwai et al., 2011a). For nitrogen fixation, primers for nifH have been recently evaluated in silico (Gaby and Buckley, 2012) and the Zf/Zr (Zehr and McReynolds, 1989) primer combination was found to have high theoretical performance, matching 92% of all reference sequences including all nifH groups I, II, and III, versus 25% for the PolF/PolR (Poly et al., 2001) primers. However, the Zf/Zr combination proved impractical in use, giving non-specific products and smeared bands on gels when used to amplify DNA extracted from soil (Gaby and Buckley, 2012). Better performing primer combinations, such as those identified by Gaby and Buckley, should be evaluated for future pyrosequencing studies taking into consideration coverage of groups important to the habitat studied.

Because they more reliably amplify DNA extracted from soil, primers PolF and PolR (Poly et al., 2001) were used in this study. These primers target an approximately 320 bp region of the nifH gene. The forward primer consisted of the 25 bp 454 A Adapter, a 10 bp barcode, followed by the 20 bp primer PolF (5′-CGT ATC GCC TCC CTC GCG CCA TCA G-barcode-TGC GAY CCS AAR GCB GAC TC-3′). The reverse primer consisted of the 25 bp 454 B Adapter and the 20 bp primer PolR (5′-CTA TGC GCC TTG CCA GCC CGC TCA GAT SGC CAT CAT YTC RCC GGA-3′). PolF and PolR are similar to Zf and Zr (Zehr and McReynolds, 1989) which we also considered using, but were modified to be less degenerate while maintaining broad coverage of nifH cluster I. When originally tested, they captured all 19 test strains, but these were limited to α-, β-, and γ-Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes (Poly et al., 2001). When tested with DNA extracted from pasture and cornfield soils, these primers produced bands of the expected size that hybridized nifH probe from Azospirillum, and did not produce non-specific products.

Initial processing of the pyrosequencing reads was performed using tools available on the Ribosomal Database Project's (RDP) FunGene pipeline web site. After reads were quality filtered and barcode sorted, FrameBot was used for translation and frame shift correction by comparing sequences to those in a reference data set containing 782 unique sequences trimmed to cover the nifH amplicon region. Sequences were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive under accession numbers ERS329752-ERS329769.

Sequencing data was processed by closest match analyses and by clustering at a 5% distance, and analyzed using the packages vegan (Oksanen et al., 2013) and phyloseq (McMurdie and Holmes, 2012) in R (R Core Team, 2013). In both cases, the number of sequences was rarefied to the minimum number of sequences per sample and empty OTUs removed. In the case of closest match, this left 3,693 sequences per sample in 160 OTUs representing 83 genera. In the case of clustering, this left 3,750 sequences per sample in 1,706 OTUs representing 81 genera.

By far, the majority of sequences were identified as Proteobacteria, further classified to α-, β-, γ-, and δ-Proteobacteria. The primers were originally designed to amplify nifH sequences from Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria, but a significant number of Verrucomicobia sequences were obtained as well (Table 4). Approximately 4% of the sequences were similar to environmental sequences that could not be classified to the phylum level, and may therefore represent novel sequences.

Table 4.

Distribution of nifH sequences recovered from Michigan and Wisconsin prairies and sites cultivated with corn and switchgrass.

| Phylum | No. sequences | % |

|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria | 80,233 | 91.619 |

| α-Proteobacteria | 35,850 | 40.954 |

| β-Proteobacteria | 19,558 | 22.236 |

| γ-Proteobacteria | 1,871 | 2.107 |

| δ-Proteobacteria | 22,954 | 26.203 |

| Cyanobacteria | 2,003 | 2.287 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 1,134 | 1.295 |

| Firmicutes | 281 | 0.321 |

| Actinobacteria | 124 | 0.142 |

| Nitrospirae | 94 | 0.107 |

| Spirochaetes | 72 | 0.082 |

| Bacteroidetes | 17 | 0.019 |

| Chlorobi | 10 | 0.011 |

| Euryarchaeota | 6 | 0.007 |

| Fusobacteria | 1 | 0.001 |

| Environmental samples* | 3,597 | 4.107 |

The reference, AF194084.1, an environmental sequence, shares 97% identity with the gene from Azospirillum sp. B510 (YP_003447953.1).

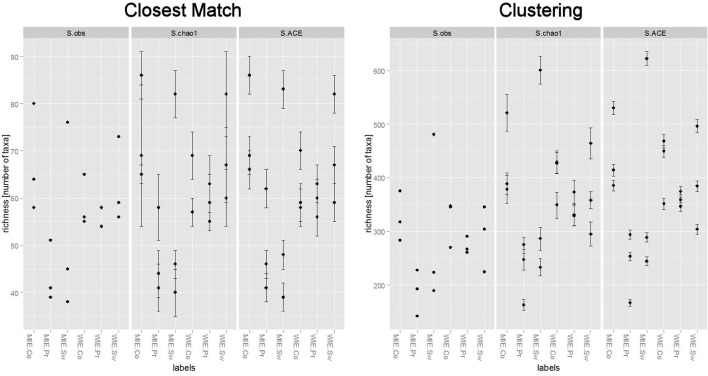

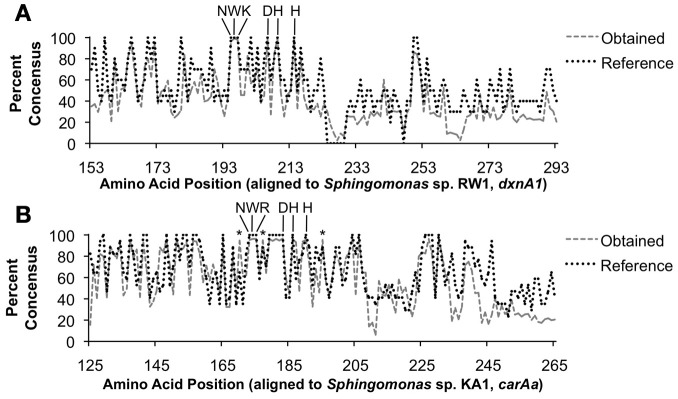

Unsurprisingly, a greater number of OTUs are observed and estimated when sequences are clustered (Figure 6). Comparisons among treatments, however, are similar. Clustering better resolves samples by estimated number of species; that is, standard errors are relatively smaller. Ordinations of data resulting from closest match and clustering are generally similar with the Michigan prairie and Michigan switchgrass sites separated from each other and from the other sites using both methods (Figure 7). In this case, the clustering based analysis provides greater resolution as it also separates Wisconsin prairie sites from the others.

Figure 6.

Differences in the number of nifH species observed and estimated between closest match (supervised method) and clustering (unsupervised method).

Figure 7.

Principal component analysis of Hellinger transformed nifH data (square root of relative abundance) on closest match and clustering data illustrating changes in relationships among sites.

Multiple F-tests were performed for difference in taxa abundance among treatments for data processed by both means. For the closest match method, 12 OTUs were found with an unadjusted p < 0.05, but none were significant after correcting for false discovery rate. For the clustering method, 46 OTUs were found with an unadjusted p < 0.05, and one of these was significant with adjusted p < 0.05. Clustr0103, genus Methylosinus, occurred exclusively in corn samples and was more abundant at the Michigan ones.

In the case of nifH presented here, the supervised and unsupervised methods provide similar results. This is because the database was tailored to nifH sequences amplifiable by the primer combination PolF/PolR and does capture most of the gene diversity in the amplicon libraries. For that reason, relatively few sequences are distant from their closest match in the database used for their identification. When this is not the case, identification to closest match may be binned into subcategories by separate bins encompassing those >90% similar to closest match, 75–90%, 50–75% similar, and those less than 50% similar. This binning by distance minimizes binning disparate sequences and is to be preferred for that reason. As an aid to interpretation, taxonomy may be assigned to clusters using a similar scheme.

Even though the difference in performance between the two methods, supervised and unsupervised, was minimal for this data set, clustering provided better estimates of total diversity, and proved more powerful in resolving differences in structure between treatments and in finding significantly different OTUs among treatments. For these reasons, it is recommended as the preferred method, and especially so when the reference database is less comprehensive than the one for nifH, which is currently the case for virtually all ecofunctional genes.

Conclusions

Amplicon functional gene sequencing provides an important companion method, and possibly in the future an alternative, provided full-length open reading frames can be obtained, to traditional strain isolation to discover desired novel genes for biotechnology. In their effect on diversity estimates and community changes with treatment, these studies illustrate that current primer coverage and specificity remain key issues that should be addressed with a robust, curated reference database. Highly divergent gene functional groups will probably need to be targeted with multiple primer sets and/or at other conserved regions, as is the case with nirK. Compared to the direct classification of sequences, clustering is the preferred method, resulting in higher estimates of total diversity and better resolution between treatments. However, estimates of community structure and differences between treatments are also impacted by the use of highly variable clustering dissimilarities. As such, the properties of each gene and the coverage of the accompanying reference database should be considered prior to formulating the downstream sequence processing methodology. Protein-coding genes, by their nature, are more varied in their sequences than rRNA genes where it is the primary structure that is constrained. Thus to expect a single degenerate primer set for a functional gene to be comprehensive is unrealistic. However, by using well-defined conditions and constant, well-performing primers, a standard subset of nature's functional guilds can be recovered and comparative studies can be done. Rarely in microbial ecology can one be comprehensive, and ecofunctional gene analysis is no exception. As with other microbial ecology studies, however, useful knowledge can still be gained with the understanding of constraints in interpretations.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the US Department of Energy, Biological Systems Research on the Role of Microbial Communities in Carbon Cycling Program (DE-SC0004601), the DOE Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE Office of Science BER DE-FC02-07ER64494) and the Superfund Research Program grant P42 ES004911-20 from the U. S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. We thank Liyou Wu for providing samples, Dr. Gerben Zylstra for his suggestions and guidance, Dr. Hideaki Nojiri and Dr. Keisuke Miyauchi for providing reference strains of previously isolated dibenzofuran degraders, and Hyung-Inn, Jihee Lee, Derek St. Louis, Christina Hazekamp and Travis Baes for technical assistance.

Appendix

Table A1.

Reference sequences used in primer design, PCR validation of primer specificity and designation of reference sequences in clusters with obtained environmental sequences.

| Cluster no. | Organism (Protein ID) | Primer group | PCR validation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d1 | S. wittichii str. RW1 (CAA51365) | 1 | dxnA1 | Wittich et al., 1992 |

| d2 | Terrabacter sp. YK3 (BAC06602) | 1 | Iida et al., 2002a | |

| d2 | Nocardioides sp. DF412 (BAG06223) | 1 | dxnA1 | Miyauchi et al., 2008 |

| d2 | Rhodococcus sp. HA01 (ACC85677) | 1 | Aly et al., 2008 | |

| d2 | Terrabacter sp. YK1 (BAG80728) | 1 | Iida et al., 2002a | |

| d2 | Rhodococcus sp. YK2 (BAG80733) | 1 | dxnA1 | Iida et al., 2002b |

| d3 | Bacillus tusciae DSM 2912 (YP_003590130) | |||

| d3 | Terrabacter sp. DBF63 (BAB55886) | 2 | dbfA1 | Kasuga et al., 2001 |

| d3 | Rhodococcus sp. HA01 (ACC85681) | 2 | Aly et al., 2008 | |

| d3 | Sphingomonas sp. LB126 (ABV68886) | 2 | Schuler et al., 2008 | |

| d3 | Paenibacillus sp. YK5 (BAE53401) | 2 | dbfA1 | Iida et al., 2006 |

| d3 | Rhodococcus sp. YK2 (BAC00802) | 2 | dbfA1 | Iida et al., 2002b |

| d3 | Rhodococcus sp. DFA3 (BAD51811) | dbfA1 | Noumura et al., 2004 | |

| d4 | Sphingomonas sp. CB3 (AAC38616) | 1 | Shepherd and Lloyd-Jones, 1998 | |

| NA | Sphingomonas sp. KA1 (YP_718182) | 2 | Urata et al., 2006 | |

| c1 | Sphingomonas sp. KA1 (YP_717942) | 3 | carAa | Urata et al., 2006 |

| c1 | Sphingomonas sp. JS1 (ACH98389) | 3 | ||

| c1 | Sphingomonas sp. KA1 (YP_717981) | carAa | ||

| c1 | Sphingomonas sp. XLDN2-5 (ADC31794) | |||

| c4 | Pseudomonas stutzeri OM1 (BAA31266) | 3 | carAa | Ouchiyama et al., 1998 |

| c4 | P. resinovorans sp. CA10 (NP_758566) | 3 | carAa | Ouchiyama et al., 1993 |

| c4 | Janthinobacterium sp. J3 (BAC56742) | 3 | carAa | Nojiri et al., 2005 |

| c4 | Pseudomonas sp. XLDN4-9 (AAY56339) | 3 | Li et al., 2004 | |

| c4 | carbazole-degrading bacterium CAR-SF (BAG30826) | 3 | Fuse et al., 2003 | |

| c4 | Pseudomonas sp. K23 (BAC56726) | |||

| c5 | Nocardioides sp. IC177 (BAD95466) | 3 | Inoue et al., 2005 | |

| NA | Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 bphA1 | none | none | |

| NA | Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 bphA1 | none | dbfA1* |

PCR validation column indicates which strains were used as PCR positive controls, and which primer set produced an amplicon with that strain. References listed detail the activity of the strain toward dioxins.

Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 produced only a faint band with the dbfA1 primer set.

Table A2.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions of the three primer sets.

| Primer Set | Target position | Sequence (5′-3′) | Ta‡ (°C) | Primer conc. (μM) | Mg2+ conc. (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dxnA1/dfdA1 | 145-150* | TACAAVGGGCTGRTTTTCGG | 51 | 1.2 | 4 |

| 312-307* | GARAAVTTVGGGAACAC | ||||

| dbfA1 | 205-210* | GGCGACGACTAYCACGTGCT | 51 | 0.8 | 3.5 |

| 373-368* | TCGAAGTTCTCGCCRTCRTC | ||||

| carAa | 69-74† | TGCCTNCAYCGHGGBGT | 63 | 0.8 | 2.5 |

| 268-263† | TTSAGHACRCCBGGSAGCCA |

These PCR conditions were optimized for the soil samples described. The target positions described are for reference amino acid sequences:

position based on Sphingomonas wittichii RW1, dxnA1, and

position based on Sphingomonas sp. KA1, carAa.

annealing temperature.

Table A3.

Primer hits for 517F/1055R, F1aCu/R3Cu, nirK1F/nirK5R with 0 mismatches to the nirK dataset.

| 517F | 1055R | F1aCu | R3Cu | nirK1F | nirK5R | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALPHA-PROTEOBACTERIA | |||||||||

| Afipia sp. | x | ||||||||

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | x | x | |||||||

| Azospirillum brasilense | |||||||||

| Azospirillum lipoferum | |||||||||

| Azospirillum sp. | |||||||||

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | x | ||||||||

| Bradyrhizobium sp. | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella abortus | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella canis | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella ceti | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella melitensis | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella microti | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella ovis | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella pinnipedialis | x | x | |||||||

| Brucella sp. | x | x | x | ||||||

| Brucella suis | x | x | |||||||

| Caulobacter segnis | |||||||||

| Chelativorans sp. | x | x | |||||||

| Hyphomicrobium denitrificans | |||||||||

| Maritimibacter alkaliphilus | x | x | x | ||||||

| Mesorhizobium alhagi | x | ||||||||

| Mesorhizobium amorphae | x | ||||||||

| Mesorhizobium australicum | |||||||||

| Mesorhizobium ciceri | x | ||||||||

| Mesorhizobium opportunistum | x | ||||||||

| Methylocella silvestris | |||||||||

| Methylocystis sp. | x | ||||||||

| Nitratireductor aquibiodomus | x | x | |||||||

| Nitrobacter hamburgensis | |||||||||

| Nitrobacter sp. | |||||||||

| Nitrobacter winogradskyi | |||||||||

| Ochrobactrum anthropi | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Ochrobactrum intermedium | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Oligotropha carboxidovorans | |||||||||

| Parvibaculum lavamentivorans | |||||||||

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis | x | ||||||||

| Phenylobacterium zucineum | |||||||||

| Rhizobium etli | x | x | x | ||||||

| Rhizobium sullae | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris | x | x | x | ||||||

| Rhodopseudomonas sp. | x | x | |||||||

| Roseobacter sp. | x | ||||||||

| Roseovarius sp. | |||||||||

| Sinorhizobium fredii | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Sinorhizobium medicae | x | x | x | ||||||

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Sinorhizobium sp. | x | x | |||||||

| Sphingomonas wittichii | |||||||||

| Starkeya novella | x | x | x | ||||||

| BETA-PROTEOBACTERIA | |||||||||

| Achromobacter cycloclastes | x | x | |||||||

| Achromobacter sp. | x | x | |||||||

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Alcaligenes faecalis | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Alcaligenes sp. | x | x | x | ||||||

| Azoarcus sp. | |||||||||

| Burkholderia mallei | |||||||||

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | |||||||||

| Burkholderia thailandensis | |||||||||

| Chromobacterium violaceum | |||||||||

| Herminiimonas arsenicoxydans | |||||||||

| Kingella denitrificans | |||||||||

| Kingella kingae | |||||||||

| Kingella oralis | x | ||||||||

| Lautropia mirabilis | |||||||||

| Methylotenera mobilis | |||||||||

| Neisseria bacilliformis | |||||||||

| Neisseria cinerea | |||||||||

| Neisseria elongata | |||||||||

| Neisseria flavescens | |||||||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | |||||||||

| Neisseria lactamica | |||||||||

| Neisseria macacae | |||||||||

| Neisseria meningitides | |||||||||

| Neisseria mucosa | |||||||||

| Neisseria polysaccharea | |||||||||

| Neisseria sicca | |||||||||

| Neisseria sp. | |||||||||

| Neisseria subflava | |||||||||

| Neisseria weaveri | |||||||||

| Nitrosomonas europaea | |||||||||

| Nitrosomonas eutropha | |||||||||

| Nitrosomonas sp. | |||||||||

| Nitrosospira briensis | |||||||||

| Nitrosospira multiformis | |||||||||

| Nitrosospira sp. | |||||||||

| Polaromonas naphthalenivorans | |||||||||

| Pusillimonas sp. | x | ||||||||

| Ralstonia pickettii | |||||||||

| Ralstonia solanacearum | |||||||||

| Ralstonia sp. | |||||||||

| Taylorella asinigenitalis | |||||||||

| Taylorella equigenitalis | |||||||||

| Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus | |||||||||

| GAMMA-PROTEOBACTERIA | |||||||||

| Cardiobacterium hominis | |||||||||

| Cardiobacterium valvarum | |||||||||

| Gallibacterium anatis | |||||||||

| Haemophilus parahaemolyticus | |||||||||

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | |||||||||

| Haemophilus paraphrohaemolyticus | |||||||||

| Haemophilus pittmaniae | |||||||||

| Idiomarina loihiensis | |||||||||

| Kangiella koreensis | |||||||||

| Mannheimia succiniciproducens | |||||||||

| Marinobacter sp. | |||||||||

| Methylomonas sp. | |||||||||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | |||||||||

| Nitrococcus mobilis | |||||||||

| Nitrosococcus halophilus | |||||||||

| Nitrosococcus oceani | |||||||||

| Oceanimonas sp. | |||||||||

| Pasteurella bettyae | |||||||||

| Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis | |||||||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | x | ||||||||

| Pseudomonas chlororaphis | x | x | |||||||

| Pseudomonas entomophila | x | x | |||||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | x | x | x | ||||||

| Pseudomonas mendocina | x | x | x | ||||||

| Pseudomonas sp. | x | x | x | ||||||

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | |||||||||

| Pseudoxanthomonas suwonensis | |||||||||

| Psychrobacter sp. | |||||||||

| Rhodanobacter fulvus | |||||||||

| Rhodanobacter sp. | |||||||||

| Rhodanobacter spathiphylli | |||||||||

| Rhodanobacter thiooxydans | |||||||||

| Salinisphaera shabanensis | |||||||||

| Shewanella amazonensis | |||||||||

| Shewanella denitrificans | x | x | |||||||

| Shewanella loihica | |||||||||

| Shewanella woodyi | |||||||||

| Thioalkalivibrio sp. | |||||||||

| BACTEROIDETES | |||||||||

| Flavobacteriaceae bacterium | |||||||||

| Flavobacterium columnare | |||||||||

| Flavobacterium johnsoniae | |||||||||

| Maribacter sp. | |||||||||

| Marivirga tractuosa | |||||||||

| Rhodothermus marinus | |||||||||

| Belliella baltica | |||||||||

| Muricauda ruestringensis | |||||||||

| Aequorivita sublithincola | |||||||||

| Solitalea Canadensis | |||||||||

| Bizionia argentinensis | |||||||||

| Capnocytophaga gingivalis | |||||||||

| Capnocytophaga sp. | |||||||||

| Capnocytophaga sputigena | |||||||||

| Chryseobacterium gleum | |||||||||

| Imtechella halotolerans | |||||||||

| Myroides odoratimimus | |||||||||

| ARCHAEA | |||||||||

| Candidatus caldiarchaeum | |||||||||

| Candidatus nitrosoarchaeum | |||||||||

| Candidatus nitrosopumilus | |||||||||

| Haloarcula hispanica | |||||||||

| Haloarcula marismortui | |||||||||

| Haloferax denitrificans | |||||||||

| Haloferax lucentense | |||||||||

| Haloferax mediterranei | |||||||||

| Haloferax volcanii | |||||||||

| Halogeometricum borinquense | |||||||||

| Halomicrobium mukohataei | |||||||||

| Halopiger xanaduensis | |||||||||

| Halorhabdus utahensis | |||||||||

| Haloterrigena turkmenica | |||||||||

| Natrinema pellirubrum | |||||||||

| Natronomonas pharaonis | |||||||||

| Nitrosopumilus maritimus | |||||||||

| CHLOROFLEXI— FIRMICUTES | |||||||||

| Chloroflexus aggregans | |||||||||

| Chloroflexus aurantiacus | |||||||||

| Chloroflexus sp. | |||||||||

| Herpetosiphon aurantiacus | |||||||||

| Sphaerobacter thermophilus | |||||||||

| Bacillus methanolicus | |||||||||

| Bacillus smithii | |||||||||

| Bacillus sp. | |||||||||

| Caldalkalibacillus thermarum | |||||||||

| Geobacillus kaustophilus | |||||||||

| Geobacillus sp. | |||||||||

| Geobacillus thermodenitrificans | |||||||||

| Geobacillus thermoglucosidans | |||||||||

| Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius | |||||||||

| Sulfobacillus acidophilus | |||||||||

| Symbiobacterium thermophilum | |||||||||

| Thermaerobacter marianensis | |||||||||

| Thermaerobacter subterraneus | |||||||||

| Thermus scotoductus | |||||||||

| ACTINOBACTERIA | |||||||||

| Acidothermus cellulolyticus | |||||||||

| Actinobacillus minor | |||||||||

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae | |||||||||

| Actinobacillus succinogenes | |||||||||

| Actinobacillus ureae | |||||||||

| Actinomyces coleocanis | |||||||||

| Actinomyces odontolyticus | |||||||||

| Actinomyces sp. | |||||||||

| Actinomyces urogenitalis | |||||||||

| Actinoplanes missouriensis | |||||||||

| Actinosynnema mirum | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium accolens | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium aurimucosum | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium efficiens | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium pseudogenitalium | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium striatum | |||||||||

| Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum | |||||||||

| Micromonospora aurantiaca | |||||||||

| Micromonospora sp. | |||||||||

| Rubrobacter xylanophilus | |||||||||

| Thermobifida fusca | |||||||||

| OTHER | |||||||||

| Gemmatimonas aurantiaca | |||||||||

| Candidatus nitrospira | |||||||||

| Leptospira biflexa | |||||||||

| Turneriella parva | |||||||||

| Chthoniobacter flavus | |||||||||

| Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum | |||||||||

| Methylacidiphilum infernorum | |||||||||

Table A4.

Primer hits for cd3af/R3cd and nirs1F/nirs6R with 0 and 2 mismatches to the nirS reference dataset.

| 0 Mismatches | 2 Mismatches | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cd3af | R3cd | nirs1F | nirS6R | cd3af | R3cd | nirs1F | nirs6R | |

| ALPHA-PROTEOBACTERIA | ||||||||

| Dinoroseobacter shibae | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Magnetospirillum magneticum | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Paracoccus denitrificans | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Paracoccus pantotrophus | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Polymorphum gilvum | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Rhodobacter sp. | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Roseobacter denitrificans | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Roseobacter litoralis | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Ruegeria pomeroyi | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Stappia aggregate | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| BETA-PROTEOBACTERIA | ||||||||

| Achromobacter sp. | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Acidovorax delafieldii | x | x | x | |||||

| Acidovorax ebreus | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Acidovorax sp. | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Alicycliphilus denitrificans | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Anaerolinea thermophile | x | x | ||||||

| Azoarcus sp. | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Bordetella petrii | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Brachymonas denitrificans | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Burkholderia cepacia | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Candidatus accumulibacter | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Comamonas denitrificans | x | x | ||||||

| Cupriavidus metallidurans | x | x | x | |||||

| Cupriavidus necator | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Cupriavidus taiwanensis | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Dechloromonas aromatica | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Dechlorosoma suillum | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Leptothrix cholodnii | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Pseudogulbenkiania ferrooxidans | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Pseudogulbenkiania sp. | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Ralstonia eutropha | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Rubrivivax benzoatilyticus | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Rubrivivax gelatinosus | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Sideroxydans lithotrophicus | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Thauera sp. | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Thiobacillus denitrificans | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| GAMMA PROTEOBACTERIA | ||||||||

| Beggiatoa sp. | ||||||||

| gamma proteobacterium | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Hahella chejuensis | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Kangiella koreensis | x | |||||||

| Marinobacter aquaeolei | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pseudomonas brassicacearum | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Pseudomonas chloritidismutans | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Pseudomonas sp. | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| nitratiruptor sp. | ||||||||

| OTHER | ||||||||

| Aromatoleum aromaticum | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Roseiflexus castenholzii | x | x | x | |||||

| Oceanithermus profundus | x | x | ||||||

| Thermus scotoductus | x | |||||||

| Thermus thermophilus | x | x | ||||||

| Candidatus kuenenia | ||||||||

| Persephonella marina | ||||||||

| Sulfurihydrogenibium sp. | ||||||||

| Hydrogenivirga sp. | x | |||||||

| Hydrogenobacter thermophilus | x | |||||||

| Hydrogenobaculum sp. | ||||||||

| Rhodothermus marinus | x | x | ||||||

| Candidatus methylomirabilis | x | x | x | |||||

| uncultured bacterium | x | x | x | x | ||||

| uncultured chloroflexi | x | |||||||

References

- Aly H., Huu N., Wray V., Junca H., Pieper D. (2008). Two angular dioxygenases contribute to the metabolic versatility of dibenzofuran-degrading Rhodococcus sp. strain HA01. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 3812–3822 10.1128/AEM.00226-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartossek R., Nicol G. W., Lanzen A., Klenk H. P., Schleper C. (2010). Homologues of nitrite reductases in ammonia-oxidizing archaea: diversity and genomic context. Eniviron. Microbiol. 12, 1075–1088 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Y., Douady C. J., Papke R. T., Walsh D. A., Boudreau M. E. R., Nesbø C. L., et al. (2003). Lateral gene transfer and the origins of prokaryotic groups. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37, 283–328 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.050503.084247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braker G., Fesefeldt A., Witzel K.-P. (1998). Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 37690–3775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braker G., Zhou J., Wu L., Devol A. H., Tiedje J. M. (2000). Nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) as functional markers to investigate diversity of denitrifying bacteria in Pacific northwest marine sediment communities.Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2096–2104 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2096-2104.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Luo X., Hu R., Wu M., Wu J., Wei W. (2010). Impacts of long-term fertilization on the composition of denitrifier communities based on nitrite reductase analyses in a paddy soil. Microb. Ecol. 60, 850–861 10.1007/s00248-010-9700-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. R., Konstantidindis K., Farris R. J., Tiedje J. M. (2010). Microbial diversity and phylogeny: extending from rRNAs to genomes, in Environmental Molecular Microbiology, eds Liu W.-T., Jansson J. K. (Norfolk: Caister Academic Press; ), 1–19 [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. R., Wang Q., Cardenas E., Fish J., Chai B., Farris R. J., et al. (2009) The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D141–D145 10.1093/nar/gkn879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S. R. (2009) A new generation of homology search tools based on probabilistic inference. Genome Inform. 23, 205–211 10.1142/9781848165632_0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. A., Chai B., Wang Q., Sun Y., Brown C. T., Tiedje J. M., et al. (2013). Functional gene pipeline and repository: tools for functional gene analysis. Terr. Microbiol. (accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field J. A., Sierra-Alvarez R. (2008) Microbial degradation of chlorinated dioxins. Chemosphere 71, 1005–1018 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuse H., Takimura O., Murakami K., Inoue H., Yamaoka Y. (2003). Degradation of chlorinated biphenyl, dibenzofuran, and dibenzo-p-dioxin by marine bacteria that degrade biphenyl, carbazole, or dibenzofuran. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67, 1121–1125 10.1271/bbb.67.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaby J. C., Buckley D. H. (2012). A comprehensive evaluation of PCR primers to amplify the nifH gene of nitrogenase. PLoS ONE 7:42149. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S. J., Prakash O., Gihring T. M., Akob D. M., Jasrotia P., Palumbo A. V., et al. (2010). Denitrifying bacteria isolated from terrestrial subsurface sediments exposed to mixed-waste contamination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3244–3254 10.1128/AEM.03069-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann E. M., Badalamenti J. P., Krajmalnik-Brown R., Halden R. U. (2012). Quantitative PCR for tracking megaplasmid-borne biodegradation potential of a model sphingomonad. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4493–4496 10.1128/AEM.00715-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heylen K., Gevers D., Vanparys B., Wittebolle L., Geets J., Boon N., et al. (2006). The incidence of nirS and nirK and their genetic heterogeneity in cultivated denitrifiers. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 2012–2021 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch A. M., McKhann H. I., Reddy A., Liao J., Fang Y., Marshall C. R. (1995). Assessing horizontal transfer of nifHDK genes in eubacteria: nucleotide sequence of nifK from Frankia strain HFPCcI3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12, 16–27 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida T., Mukouzaka Y., Nakamura K., Kudo T. (2002a). Plasmid-borne genes code for an angular dioxygenase involved in dibenzofuran degradation by Terrabacter sp. strain YK3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 3716–3723 10.1128/AEM.68.8.3716-3723.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida T., Mukouzaka Y., Nakamura K., Yamaguchi I., Kudo T. (2002b). Isolation and characterization of dibenzofuran-degrading Actinomycetes: analysis of multiple extradiol dioxygenase genes in dibenzofuran-degrading Rhodococcus species. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66, 1462–1472 10.1271/bbb.66.1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida T., Nakamura K., Izumi A., Mukouzaka Y., Kudo T. (2006). Isolation and characterization of a gene cluster for dibenzofuran degradation in a new dibenzofuran-utilizing bacterium, Paenibacillus sp. strain YK5. Arch. Microbiol. 184, 305–315 10.1007/s00203-005-0045-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K., Habe H., Yamane H., Omori T., Nojiri H. (2005). Diversity of carbazole-degrading bacteria having the car gene cluster: Isolation of a novel gram-positive carbazole-degrading bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245, 145–153 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai S., Chai B., Sul W. J., Cole J. R., Hashsham S. A., Tiedje J. M. (2010). Gene-targeted-metagenomics reveals extensive diversity of aromatic dioxygenase genes in the environment. ISME J. 4, 279–285 10.1038/ismej.2009.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai S., Chai B., da C Jesus E., Penton C. R., Lee T. K., Cole J. R., et al. (2011a). Gene-targeted-metagenomics (GT-metagenomics) to explore the extensive diversity of genes of interest in microbial communities, in Handbook of Molecular Microbial Ecology I: Metagenomics and Complementary Approaches, ed de Bruijn Frans J. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publ; ), 235–244 [Google Scholar]

- Iwai S., Johnson T. A., Chai B., Hashsham S. A., Tiedje J. M. (2011b). Comparison of the specificities and efficacies of primers for aromatic dioxygenase gene analysis of environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 3551–3557 10.1128/AEM.00331-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. M., Stres B., Rosenquist M., Hallin S. (2008). Phylogenetic analysis of nitrite, nitric oxide, and nitrous oxide respiratory enzymes reveal a complex evolutionary history for denitrification. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1955–1966 10.1093/molbev/msn146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga K., Habe H., Chung J. S., Yoshida T., Nojiri H., Yamane H., et al. (2001). Isolation and characterization of the genes encoding a novel oxygenase component of angular dioxygenase from the gram-positive dibenzofuran-degrader Terrabacter sp. strain DBF63. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 283, 195–204 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni P. S., Crespo J. G., Afonso C. A. M. (2008). Dioxins sources and current remediation technologies—a review. Environ. Int. 34, 139–153 10.1016/j.envint.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh M. B., Pellizari V. H., Uhlík O., Sutka R., Rodrigues J., Ostrom N. E., et al. (2007). Biphenyl-utilizing bacteria and their functional genes in a pine root zone contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). ISME J. 1, 134–148 10.1038/ismej.2007.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Xu P., Blankespoor H. D. (2004). Degradation of carbazole in the presence of non-aqueous phase liquids by Pseudomonas sp. Biotechnol. Lett. 26, 581–584 10.1023/B:BILE.0000021959.00819.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie P. J., Holmes S. (2012). phyloseq: a Bioconductor package for handling and analysis of high-throughput phylogenetic sequence data. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 17, 235–246 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michotey V., Mejean V., Bonin P. (2000). Comparison of methods for quantification of cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria in marine samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 1564–1571 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1564-1571.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi K., Sukda P., Nishida T., Ito E., Matsumoto Y., Masai E., et al. (2008). Isolation of dibenzofuran-degrading bacterium, Nocardioides sp. DF412, and characterization of its dibenzofuran degradation genes. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105, 628–635 10.1263/jbb.105.628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam I. H., Kim Y. M., Schmidt S., Chang Y. S. (2006). Biotransformation of 1,2,3-tri- and 1,2,3,4,7,8-hexachlorodibenzo-p- dioxin by Sphingomonas wittichii strain RW1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 112–116 10.1128/AEM.72.1.112-116.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri H., Ashikawa Y., Noguchi H., Nam J.-W., Urata M., Fujimoto Z., et al. (2005). Structure of the terminal oxygenase component of angular dioxygenase, carbazole 1,9a-dioxygenase.J. Mol. Biol. 351, 355–370 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noumura T., Habe H., Widada J., Chung J.-S., Yoshida T., Nojiri H., et al. (2004). Genetic characterization of the dibenzofuran-degrading Actinobacteria carrying the dbfA1A2 gene homologues isolated from activated sludge. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 239, 147–155 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J. F., Blanchet G., Kindt R., Legendre P., Minchin P. R., O'Hara R. B., et al. (2013). Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-7. Avialble online at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

- Ouchiyama N., Miyachi S., Omori T. (1998). Cloning and nucleotide sequence of carbazole catabolic genes from Pseudomonas stutzeri strain OM1, isolated from activated sludge. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 44, 57–63 10.2323/jgam.44.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchiyama N., Zhang Y., Omori T., Kodama T. (1993). Biodegradation of carbazole by Pseudomonas spp. CA06 and CA10. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57, 455–460 10.1271/bbb.57.45512501294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K., Biasi C., Horn M. A. (2012). Contrasting denitrifier communities relate to contrasting N2O emission pattern from acidic peat soils in arctic tundra. ISME J. 6, 1058–1077 10.1038/ismej.2011.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K., Horn M. A. (2012). Actinobacterial nitrate reducers and proteobacterial denitrifiers are abundant in N2O-metabolizing palsa peat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5584–5596 10.1128/AEM.00810-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot L., Hallin S., Schloter M., Donald L. S. (2007). Ecology of denitrifying prokaryotes in agricultural soil. Adv. Agron. 96, 249–305 10.1016/S0065-2113(07)96003-414711656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poly F., Monrozier L. J., Bally R. (2001). Improvement in the RFLP procedure for studying the diversity of nifH genes in communities of nitrogen fixers in soil. Res. Microbiol. 152, 95–103 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)01172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieme A., Braker G., Tiedje J. M. (2002). Diversity of nitrite reductase (nirK and nirS) gene fragments in forested upland and wetland soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 1893–1900 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1893-1900.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, (2013). R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, (Vienna). ISBN: 3-900051-07-0. Available online at: http://www.R-project.org/

- Schuler L., Ni Chadhain S. M., Jouanneau Y., Meyer C., Zylstra G. J., Hols P., et al. (2008) Characterization of a novel angular dioxygenase from fluorene-degrading Sphingomonas sp. strain LB126. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1050–1057 10.1128/AEM.01627-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J. M., Lloyd-Jones G. (1998). Novel carbazole degradation genes of Sphingomonas CB3: Sequence analysis, transcription, and molecular ecology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247, 129–135 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throbäck I. N., Enwall K., Jarvis A., Hallin S. (2004). Reassessing PCR primers targeting nirS, nirK and nosZ genes for community surveys of denitrifying bacteria with DGGE. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49, 401–417 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treusch A. H., Leininger S., Kletzin A., Schuster S. C., Klenk H.-P., Schleper C. (2005). Novel genes for nitrite reductase and Amo-related proteins indicate a role of uncultivated mesophilic crenarchaeota in nitrogen cycling. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1985–1995 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urata M., Uchimura H., Noguchi H., Sakaguchi T., Takemura T., Eto K., et al. (2006). Plasmid pCAR3 contains multiple gene sets involved in the conversion of carbazole to anthranilate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3198–3205 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3198-3205.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Quensen, III J. F., Fish J. A., Lee T. K., Sun Y., Tiedje J. M., et al. (2013). Ecological patterns of nifH genes in four terrestrial climatic zones explored with targeted metagenomics using FrameBot, a new informatics tool. mBio 4:e00592-13 10.1128/mBio.00592-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. A., Rice C. W., Owensby C. E. (2011). Nitrogen competition in a tallgrass prairie ecosystem exposed to elevated carbon dioxide. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 65, 340–346 10.2136/sssaj2001.652340x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wittich R. M., Wilkes H., Sinnwell V., Francke W., Fortnagel P. (1992) Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 1005–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr J. P., McReynolds M. A. (1989). Use of degenerate oligonucleotides for amplification of the nifH gene from the marine Cyanobacterium Trichodesmium thiebautii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55, 2522–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. Z., Bruns M. A., Tiedje J. M. (1996). DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 316–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]