Abstract

BACKGROUND

Behavioral economic demand curves measure individual differences in motivation for alcohol and have been associated with problematic patterns of alcohol use, but little is known about the variables that may contribute to elevated demand. Negative visceral states have been theorized to increase demand for alcohol and to contribute to excessive drinking patterns, but little empirical research has evaluated this possibility. The present study tested the hypothesis that symptoms of depression and PTSD would be uniquely associated with elevated alcohol demand even after taking into account differences in typical drinking levels.

METHOD

An Alcohol Purchase Task (APT) was used to generate a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement in a sample of 133 college students (50.4% male, 64.4% Caucasian, 29.5% African-American) who reported at least one heavy drinking episode (5/4 or more drinks in one occasion for a man/woman) in the past month. Participants also completed standard measures of alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and PTSD.

RESULTS

Regression analyses indicated that symptoms of depression were associated with higher demand intensity (alcohol consumption when price = 0; ΔR2 = .05, p = .002) and lower elasticity (ΔR2 = .04, p = .03), and that PTSD symptoms were associated with all five demand curve metrics (ΔR2 = .04 – .07, ps < .05).

CONCLUSIONS

These findings provide support for behavioral economic models of addiction that highlight the role of aversive visceral states in increasing the reward value of alcohol and provide an additional theoretical model to explain the association between negative affect and problematic drinking patterns.

Keywords: behavioral economics, alcohol abuse, reinforcement, demand curve, comorbidity

1. INTRODUCTION

Behavioral economics views drug consumption as operant behavior that is maintained by the reinforcing properties of drugs (Madden and Bickel, 2010; Vuchinich and Heather, 2003). Persistent overvaluation of drug-related rewards is theorized to contribute to the development of substance use disorders. Behavioral economic approaches to substance abuse attempt to understand the conditions that give rise to the overvaluation and overconsumption of alcohol and other drugs (Rachlin, 2000), and to develop interventions to reduce the value of drug rewards and increase the value of alternative reinforcers (Higgins et al., 2004; Murphy et al., in press).

Behavioral economic researchers typically use a demand curve analysis to quantify the relative value of a reinforcer (Hursh and Silberburg, 2008). Demand refers to the amount of a commodity sought or consumed by an individual at a given price and, by plotting consumption as a function of price or response cost, a demand curve can be generated that provides a multidimensional assessment of the relative value of the commodity. Alcohol demand curves can be generated using in vivo consumption in a laboratory setting using progressive-ratio schedules (Hursh and Silberburg, 2008; Johnson and Bickel, 2006) or by hypothetical alcohol purchase tasks (Jacobs and Bickel, 1997; Murphy and MacKillop, 2006) that can be quickly completed in clinical or other settings. Participants reported consumption level at each price generates both a consumption curve and an accompanying expenditure curve (expenditure plotted as a function of price). These demand and expenditure curves provide multiple indices of the relative value of alcohol that are conceptually related, but nonetheless distinct (MacKillop et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2009): consumption at zero price (i.e., intensity), the price that reduces consumption to zero (i.e., breakpoint), maximum expenditure (Omax); price associated with maximum expenditure (Pmax), and the proportionate slope of the demand curve (elasticity). Demand indices have been psychometrically validated and exhibit good test–retest reliability (Murphy et al., 2009; Few et al. in press), close correspondence between choices for hypothetical and actual outcomes, (Amlung et al., 2011), and significant associations with in vivo consumption (MacKillop and Tidey, 2011).

These indices of alcohol demand are associated with alcohol misuse in both the general population and in young adults. Young adults who attend college report higher levels of alcohol consumption than any other age or demographic group (Hingson, 2010) and some studies have suggested that rates of drinking among college students are rising (Hingson et al., 2009). Demand curves approaches may be especially relevant as individual difference in indices of strength of motivation for alcohol among college student drinkers, who show significant variability in the relative malleability of their drinking patterns (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007) and in long term drinking trajectories (Campbell and Demb, 2008; Littlefield et al., 2010). Murphy and MacKillop (2006) found that several indices of demand (intensity, Omax, and breakpoint) were positively related to average consumption per week, number of heavy drinking episodes, and alcohol-related problems in a college sample. Further, when comparing the lighter drinkers (no heavy drinking in typical week) to the heavier drinkers (at least one heavy drinking episode in typical week), the heavier drinkers had higher values for Intensity, Omax, and Breakpoint. Another study found that alcohol demand moderated the relation between impulsivity-related traits and drinking (Smith et al., 2010); negative trait urgency and sensation seeking were associated with alcohol use and problems only among individuals with higher demand for alcohol. Importantly, individual differences in demand curve measures of alcohol reinforcement have also been associated with changes in drinking following a brief motivational intervention for heavy drinking college students. Specifically, drinkers with higher maximum expenditure (i.e., Omax) for alcohol and lower price sensitivity (i.e., high breakpoint, Pmax, and elasticity) at baseline reported greater drinking six months following the intervention in models that controlled for baseline drinking level (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007). Thus, individuals with elevated demand may not respond to standard motivational interventions that attempt to highlight the costs and risks associated with drinking. Collectively, these results provide support for the validity of demand curve approaches to characterizing alcohol reward value and suggest that elevated demand for alcohol may be indicative of a more problematic and less malleable drinking pattern, even among students with relatively similar heavy drinking patterns.

1.1. Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) may contribute to elevated alcohol demand

Some behavioral economic models of addiction emphasize the role of visceral factors such as craving or negative affect as an influence on the relative value of drug-related rewards (Laibson, 2001; Lowenstein, 1999, 2007). These aversive visceral states are theorized to shift an individual’s preferences among the various behavioral options available, increasing the probability that drinking will be selected over other alternatives (c.f., Shiffman, 2009; Tiffany and Wray, 2009). Mental health concerns such as depression and PTSD are significant issues among college students (ACHA, 2009; Dawson, 2005; Geisner et al., 2004) and both conditions have been linked to higher levels of alcohol use (Edwards et al., 2006; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Pedrelli et al., 2011; Weitzman, 2004). Other studies suggest that depression or PTSD symptoms may not be related to drinking level, but may predict levels of alcohol problems (Dennhardt and Murphy, 2011; McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2010). Additionally, depression and PTSD have been found to predict poor response to alcohol interventions, perhaps due to the fact that alcohol misuse among persons with depression or PTSD often serves as a maladaptive coping strategy (Geisner et al., 2007; Hien et al., 2000; Kaysen et al., 2007; Ouimette et al., 1998). Research has also found that although heavy drinking generally decreases after college, the subset of individuals who continue to drink heavily in the post-college years exhibited elevated levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms while in college (Costanzo et al., 2007). Such findings suggest that high depression and/or anxiety may increase the reinforcing value of alcohol, but to date no research has directly addressed the question of whether or not these symptoms are a unique risk factor for elevated alcohol demand.

One laboratory study examined alcohol reward value following a negative affect manipulation (Rousseau et al., 2011). Alcohol reward value was measured with a multiple choice procedure (Griffiths et al., 2006) that estimated the monetary equivalent of a standard dose of alcohol through a series of discrete choices between alcohol and specific monetary amounts. There was no main effect for mood state, but among students who reported higher levels of coping-related drinking motives, the negative mood induction increased alcohol reward value. These results provide partial support for the role of an acute negative affective state in increasing alcohol reward value. However, to our knowledge no studies have examined the role of persistent symptoms of negative affect on the relative valuation of alcohol, or examined the relations between negative affect and alcohol reward value using a demand curve measure. Whereas the multiple choice procedure establishes the monetary value of a standard drink, a demand curve analysis provides a dynamic and multifaceted measure of alcohol motivation or reward value that includes both maximum consumption at low price, maximum alcohol expenditures, and the relative price sensitivity of consumption (MacKillop et al., 2009). The goal of the current study was to examine whether symptoms of depression and PTSD are associated with increased alcohol demand. We examined depression and PTSD because these disorders have shown consistent associations with problematic patterns of substance use in a variety of samples. We hypothesized that symptoms of depression and PTSD would show significant positive associations with alcohol demand, and that this relation would not be accounted for by covariates such as gender or drinking levels. Support for this hypothesis would advance behavioral economic models of addiction by identifying unique predictors of alcohol demand within a sample of heavy drinking young adults.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

Participants were 133 undergraduate students (49.6% women, 50.4% men) from a large public university in the southern United States. Students were eligible to participate in if they were at least 18 years old and reported one or more heavy drinking episodes (5/4 drinks on one occasion for a man/woman) in the past month. The sample was ethnically diverse; 64.3% of participants identified as European American, 29.5% as African American, 2.3% as Hispanic/Latino, 2.3% as Native American, 0.8% as Asian, and 0.8% as Hawaiian.

2.2 Procedure

All procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Data for this study were derived from the baseline assessment of a larger study that examined a brief intervention for heavy drinking college students (for more details, see Murphy et al., 2010). Participants were recruited from a required university-wide course where they completed a screening evaluation. Eligible students were contacted by phone or email to participate in the clinical trial. Students who agreed to participate were invited to a private research room in the psychology building to complete the assessment battery as part of the baseline assessment for the clinical trial. The study measures were all administered via written self-report and included indices of alcohol and drug use, related consequences, and a variety of possible risk factors for alcohol and drug use (e.g., personality and behavioral economic variables). Students gave written informed consent prior to the screening survey and again before the baseline assessment.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985) was used to measure weekly alcohol consumption. On the DDQ, participants estimate the total number of standard drinks they consumed on each day during a typical week in the past month. Participants were also asked the number of times in the past month that they engaged in a heavy drinking episode (5/4 drinks for men/women). The DDQ has been used frequently with college students and is a reliable measure that is highly correlated with self-monitored drinking reports (Kivlahan et al., 1990).

2.3.2. Alcohol Purchase Task (APT)

Demand for alcohol was measured using the APT (Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). On this version of the APT participants were presented with a hypothetical party scenario and asked how many drinks they would purchase and consume at 17 different prices. The APT included the following instructions: In the questionnaire that follows we would like you to pretend to purchase and consume alcohol. Imagine that you and your friends are at a party on a weekend night from 9:00 p.m. until 2:00 a.m. to see a band. Imagine that you do not have any obligations the next day (i.e., no work or classes). The following questions ask how many drinks you would purchase at various prices. The available drinks are standard size domestic beers (12 oz.), wine (5 oz.), shots of hard liquor (1.5 oz.), or mixed drinks containing one shot of liquor. Assume that you did not drink alcohol or use drugs before you went to the party, and that you will not drink or use drugs after leaving the party. You cannot bring your own alcohol or drugs to the party. Also, assume that the alcohol you are about to purchase is for your consumption only. In other words, you can’t sell the drinks or give them to anyone else. You also can’t bring the drinks home. Everything you buy is, therefore, for your own personal use within the 5 hour period that you are at the party. Please respond to these questions honestly, as if you were actually in this situation. Participants were then asked, “How many drinks would you consume if they were ___ each?” ranging from $0 (free) to $3.00 increasing by 50-cent increments, $3.00 to $10.00 increasing by $1.00 increments, and $10.00 to $20.00 increasing by $5.00 increments. Participants completed three versions of the APT that differed as a function of next-day responsibility (no responsibility, next day class, next day test; see Skidmore and Murphy, 2011). The present analyses focused on the demand curves generated from the no-responsibility condition, which was always administered prior to the next-day class/test conditions and most closely resembles the standard demand curve measures that have shown associations with alcohol-related problems in other research studies.

Demand curves are generated by plotting participants’ reported consumption as a function of price. Expenditure estimates are computed by multiplying reported consumption by each of the 17 price values, and are also plotted as a function of price. The resulting demand and expenditure curves yield four indices which can be observed directly from the consumption or expenditure data. These include a) intensity of demand: consumption when drinks are free, b) Omax: greatest expenditure value, c) Pmax: the price associated with Omax at which demand becomes elastic, and d) breakpoint: the first price at which consumption is 0.

In addition to these indices observed from the raw alcohol consumption and expenditure data, demand curves were fit to the alcohol consumption responses for each participant using an equation to generate estimates of elasticity of demand, which cannot be observed from raw data. It is derived from the following exponential equation (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008): log Q = 1og Q0 + k (e −αP − 1). In this equation, Q represents the quantity consumed, Q0 represents consumption at price = 0, k specifies the range of the dependent variable (alcohol consumption) in logarithmic units, P specifies price, and α specifies the rate of change in consumption with changes in price (elasticity). The value of k is constant across all curve fits. For the current study, k = 2.834, which is the value that was derived when the sample mean consumption values were fit to Equation 1. Hursh and Silberberg (2008) recommend holding k constant to allow for individual differences in elasticity to be scaled with a single parameter (α) which is standardized and independent of the magnitude of the reinforcer. Larger alpha values reflect more elastic demand (greater price sensitivity). Demand curves were fit using the calculator provided on the Institute for Behavioral Resources website (http://www.ibrinc.org/index.php?id=70) which is based on Hursh and Silberberg (2008). When fitting the data to Equation 1, zero values (which cannot be log transformed) were replaced by an arbitrarily low but nonzero value of .01 (Jacobs and Bickel, 1999).

2.3.3. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants are given 20 statements (e.g., “I had crying spells”) and rate how often in the past week they have felt that way ranging from 0 = Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) to 3 = Most or all of the time (5–7 days). Four of the items are reverse scored (e.g., “I was happy”). The CES-D has been shown to be reliable for assessing depressive symptoms across racial, gender, and age categories (Knight et al., 1997). Internal consistency for CES-D in this sample was .84.

2.3.4. Trauma History Screen (THS)

The THS (Carlson et al., 2011) was used to assess traumatic experiences. The THS queries about lifetime exposure to 14 potentially traumatic events and further assesses criterion A for PTSD as specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000) through the inclusion of four dichotomously (Yes/No) rated questions: two that inquire about actual or threatened physical harm (“When this happened, did anyone get hurt or killed?” and “When this happened were you afraid that you or someone else might get hurt or killed?”) and if the person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror (“When this happened did you feel very afraid, helpless, or horrified?”). The THS has demonstrated adequate reliability and convergent validity in a range of samples including college students (Carlson et al., 2011).

2.3.5. Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD)

The Primary Care-PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD; Prins et al., 2003) is a 4-item screening questionnaire designed to screen for PTSD. Items assess symptoms related to re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, and numbing. Each item is rated dichotomously (Yes/No) and a total score of 3 or 4 is considered a positive screen. The PC-PTSD has been shown to have good psychometric properties in a variety of settings (Bliese et al., 2008). In this study, only participants who reported having experienced a traumatic event consistent with the DSM-IV definition of a trauma on the THS were asked to complete the PC-PTSD items (n = 91 or 68.4% of the sample). Prins et al., (2003) found the PC-PTSD demonstrated sound psychometric properties with sensitivity of .78 and specificity of .87 using a cutoff score of 3. Internal consistency for PC-PTSD in this sample was .67.

2.4. Data analysis plan

All outliers were corrected using Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2001) recommendations, in which any values greater than 3.29 SDs above the mean were changed to one unit greater than the greatest non-outlier value. Additionally, variables that were skewed or kurtotic were transformed using square root transformations. Pearson correlations were used to analyze the bivariate associations between alcohol consumption, symptoms of depression, symptoms of PTSD, and the demand curve indices of alcohol reinforcing efficacy. Finally, separate hierarchical regression analyses that controlled for gender, ethnicity, and alcohol consumption (weekly drinking) were run. Controlling for drinking allowed us to determine if there was a unique relation between the mood variables and alcohol demand.

3 RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive statistics and adequacy of demand curve model fit

Descriptive data for all variables are included in Table 1. Thirty-four percent of participants (n = 44) exceeded the threshold of 16 that has been used to indicate high depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977) and 19.8% (n = 17) of participants screened positive for PTSD (based on a cut score of 3 on the PC-PTSD). As described above, elasticity estimates were generated with an exponential demand curve equation (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008). This equation provided an excellent fit (R2 = .98) for the aggregated data (i.e., sample mean consumption values), but only an adequate fit to individual participant data (mean R2 = .60). Although there is no accepted criterion for adequacy of demand-curve fit, and R2 may not function well as a measure of curve fit with nonlinear models (Johnson and Bickel, 2008), the authors used a similar criterion as Reynolds and Schiffbauer (2004) and only included elasticity values for analyses when the demand equation accounted for at least 30% of the variance in the participant’s consumption (40 participants were excluded from the elasticity analyses, but not the other analyses, for this reason). There were no significant demographic differences between participants with and without valid elasticity values, but participants without valid values reported lower weekly drinking levels, t (131) = −2.56, p = .003. An examination of the data revealed that the poor curve fits were often due to having very few non-zero consumption values on the APT.

Table 1.

Pearson Correlations among Alcohol Consumption (Drinks per Week and Binge Episodes), Mood (Depression and PTSD Symptoms), and Alcohol Demand (Intensity, Breakpoint, Omax, Pmax, and Elasticity).

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Drinks Per Week |

15.86 (13.61) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. | Binge Episodes |

5.54 (4.91) | .837** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. | Depression | 13.26 (7.30) | −.050 | .036 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. | PTSD Symptoms |

1.42 (1.33) | −.015 | .040 | .382** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. | Intensity | 9.93 (5.98) | .555** | .554* | .191* | .188 | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. | Breakpoint | 9.05 (5.40) | .093 | .138 | .151 | .287** | .274** | 1.00 | |||

| 7. | Omax | 16.95 (10.76) | .511** | .493** | .157 | .263* | .678** | .682** | 1.00 | ||

| 8. | Pmax | 3.84 (2.43) | −.063 | −.018 | .131 | .320** | −.031 | .673** | .505** | 1.00 | |

| 9. | Elasticity | .06 (.06) | −.303** | −.303** | −.267** | −.280* | −.394** | −.482** | −.565** | −.327** | 1.00 |

p <.05.

p < .01.

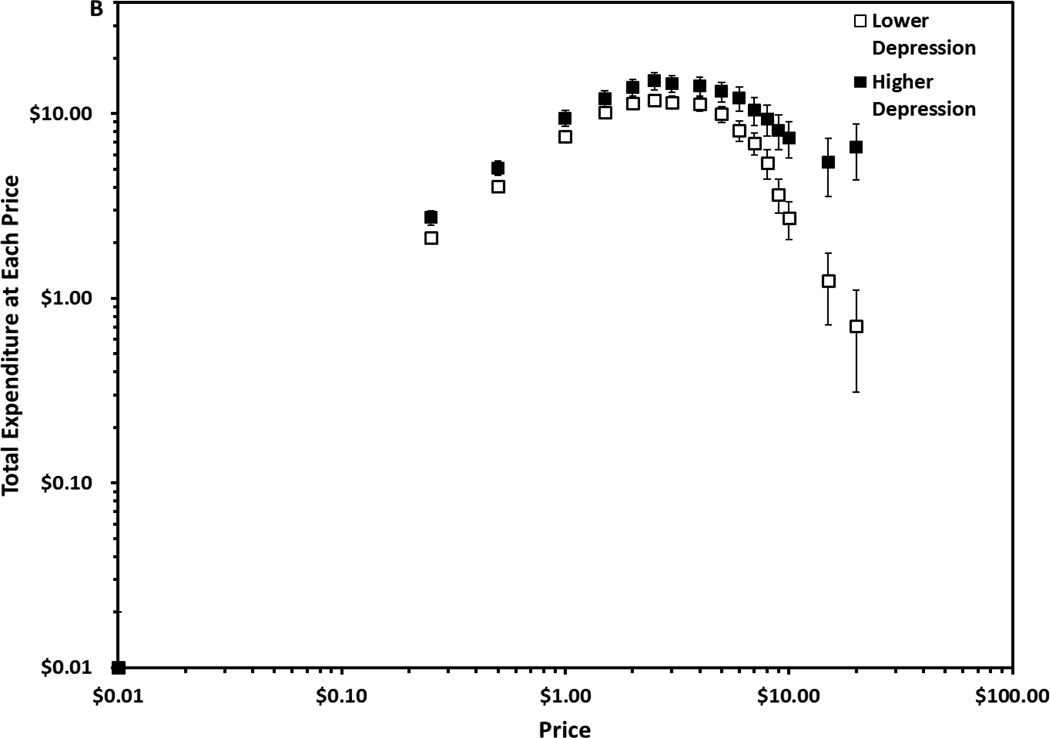

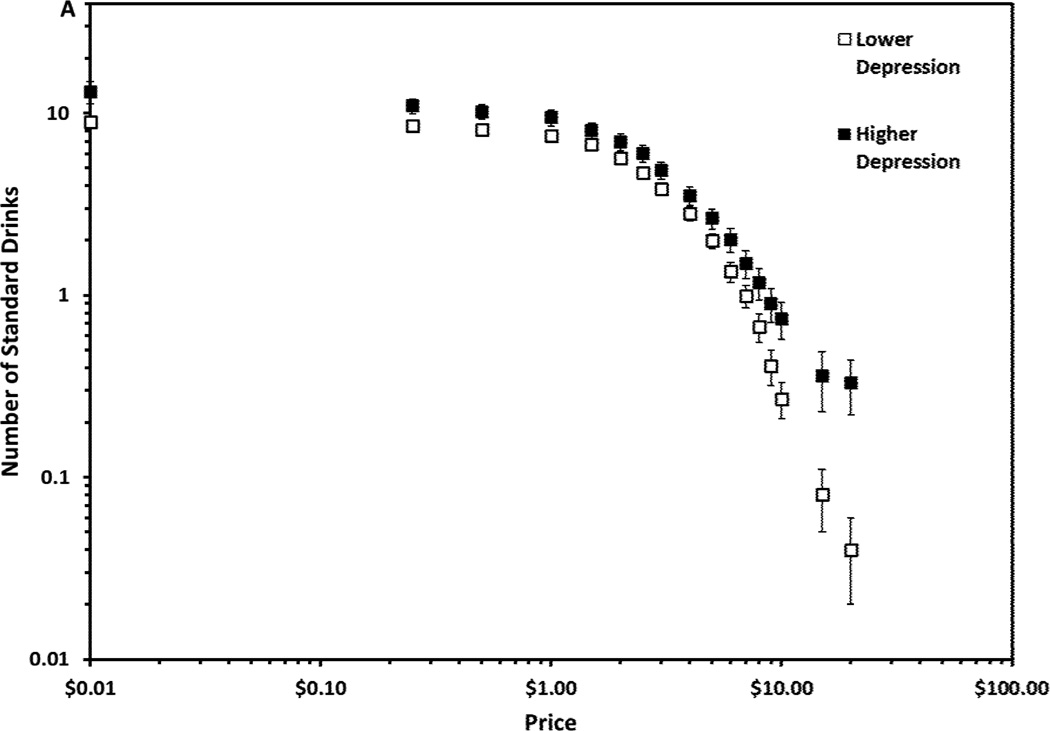

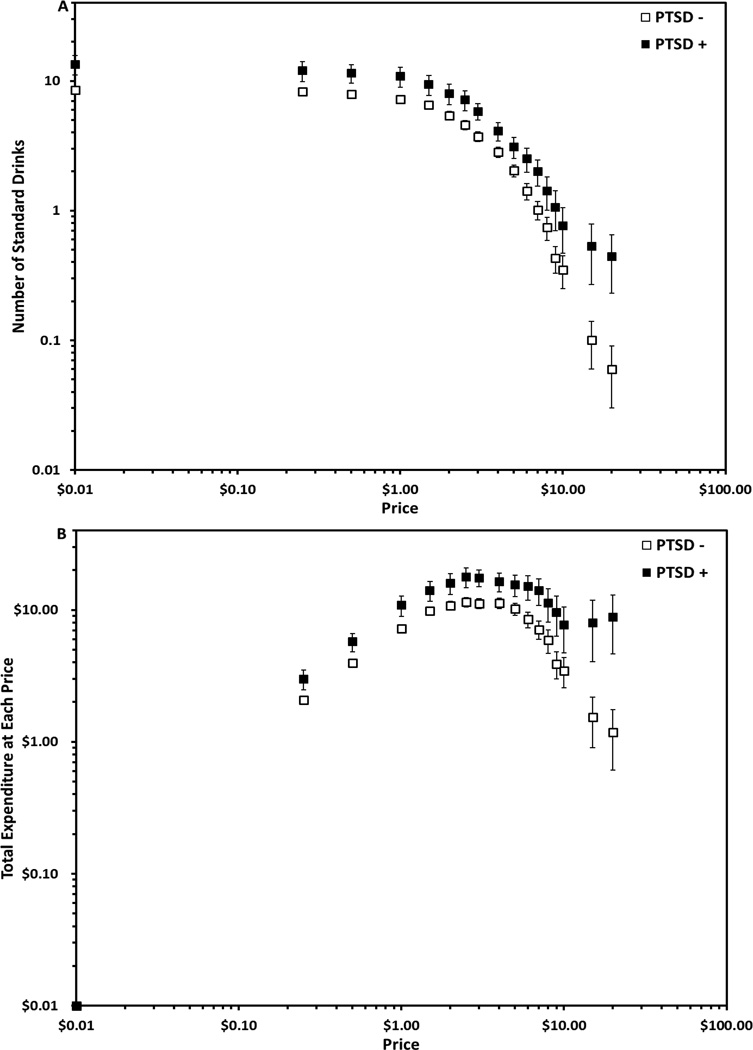

3.2. Associations between alcohol use, symptoms of depression, symptoms of PTSD, and alcohol demand

Table 1 includes bivariate correlations among the study variables. Neither depression nor PTSD symptoms were directly associated with alcohol consumption (weekly drinking or heavy drinking). Depression and PTSD symptoms demonstrated modest but significant positive correlations with one another, and the demand indices were strongly related to one another. Of the demand indices, intensity, Omax and elasticity demonstrated the strongest and most consistent associations with the alcohol consumption variables. Depression symptoms were significantly associated with intensity and elasticity; greater depression was associated with greater maximum consumption demand and more inelastic demand for alcohol (less price sensitivity). PTSD symptoms demonstrated significant associations with all demand indices other than intensity in the hypothesized direction. To illustrate the relations between alcohol demand and the dichotomous measures of depression and PTSD, Figures 1 and 2 plot alcohol demand and expenditure curves for individuals who scored above and below the threshold for depression and PTSD, respectively. Curves are plotted in double log coordinates to illustrate differences in the slopes (elasticity) of the curves.

Figure 1.

The top panel depicts the mean (± 1 Standard Error of the Mean; SEM) number of drinks (hypothetical) that students with lower depression (n = 87) and higher depression (n = 44) would purchase as a function of price plotted in conventional double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality. Depression categories were determined by the CES-D cut off score of 16. The bottom panel depicts the mean (± 1 SEM) expenditure on drinks (hypothetical) at each price by students with lower and higher depression plotted in conventional double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality.

Figure 2.

The top panel depicts the mean (± 1 SEM) number of drinks (hypothetical) that students with (n = 17) and without (n = 69) a PTSD positive screen would purchase as a function of price plotted in conventional double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality. PTSD categories were based on a cut-score of 3 on the PC-PTSD. The bottom panel depicts the mean (± 1 SEM) expenditure on drinks (hypothetical) at each price by students with and without a PTSD positive screen plotted in conventional double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality.

3.2.1. Hierarchical regression analyses

In models that controlled for alcohol consumption, gender, and ethnicity, higher levels of depression symptoms significantly predicted higher demand intensity, ΔR2 = .05, F(4, 128) = 17.70, p = .002 and lower elasticity, ΔR2 = .04, F(4, 96) = 6.04, p = .03 (See Table 2). Similarly, increased number of PTSD symptoms significantly predicted higher demand intensity, ΔR2 = .04, F(4, 88) = 15.82, p = .01, greater maximum expenditure (Omax), ΔR2 = .06, F(4, 88) = 14.22, p = .006, greater maximum inelastic price (Pmax), ΔR2 = .07, F(4, 87) = 3.13, p = .01, higher prices at breakpoint, ΔR2 = .04, F(4, 88) = 4.43, p = .05, and less sensitivity to increasing prices (elasticity), ΔR2 = .05, F(4, 67) = 3.66, p = .05 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Examining Number of Depression and PTSD Symptoms Predicting Alcohol Demand (Intensity, Breakpoint, Omax, Pmax, & Elasticity)†

| Reinforcing Efficacy Indices | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity |

Breakpoint |

Omax |

Pmax |

Elasticity |

||||||

| Predictor | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β |

| Depression Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Step 1 | .31*** | .12** | .29*** | .07* | .17*** | |||||

| Drinks Per Week |

.48*** | .29** | .60*** | .08 | −.44*** | |||||

| Gender | −.08 | .25* | .12 | .14 | −.21* | |||||

| Ethnicity | −.12 | .26** | .08 | .23* | −.14 | |||||

| Step 2 | .05** | .01 | .02 | .01 | .04* | |||||

| Depression | .24** | .08 | .14 | .09 | −.21* | |||||

| Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Total R2 | .36** | .13 | .30 | .08 | .21* | |||||

| N | 128 | 128 | 128 | 126 | 96 | |||||

| PTSD Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Step 1 | .39*** | .14** | .35*** | .06 | .14* | |||||

| Drinks Per Week |

.55*** | .36** | .63*** | .11 | −.37* | |||||

| Gender | −.11 | .23* | .04 | .14 | −.14 | |||||

| Ethnicity | .05 | .25* | .09 | .14 | .00 | |||||

| Step 2 | .04** | .04* | .06** | .07** | .05* | |||||

| PTSD symptoms |

.22** | .21* | .25** | .28** | −.24* | |||||

| Total R2 | .43** | .17* | .40** | .13** | .19* | |||||

| n | 88 | 88 | 88 | 87 | 67 | |||||

Forty participants had missing elasticity data due to poor curve fit.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

4. DISCUSSION

This study used a behavioral economic demand curve approach to investigate whether young adult heavy drinkers with symptoms of depression or PTSD exhibited greater alcohol reward value. Depressive symptoms were associated with greater consumption levels when drinks were free and with more inelastic demand. PTSD symptoms were associated with elevations on all five demand metrics. Importantly, these effects were present in models that controlled for typical drinking level (as well as gender and ethnicity), which suggests that the association between these mood-related symptoms and elevated demand is not merely a product of greater typical drinking levels. It is interesting that symptoms of depression or PTSD were not associated with participants’ reports of their typical weekly drinking levels. This may be due in part to limited variability in alcohol consumption related to the study eligibility requirements (all participants reported past-month heavy drinking), but may also suggest that both psychiatric symptoms and elevated demand are associated with elements of alcohol-related pathology that are at least partially distinct from elevated weekly alcohol consumption. Indeed, previous research suggests that individuals with symptoms of depression or PTSD may incur more harm associated with their drinking, relative even to students drinking similar amounts of alcohol (Dennhardt and Murphy, 2011; McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2010). Prior research also indicates that demand curves are related to alcohol problems even after controlling for consumption levels (Murphy et al., 2009), an effect that is partially mediated by drinking to cope with stress (Yurasek et al., 2011).

Although more research is needed to determine the clinical implications of elevated demand (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007), laboratory and theoretical behavioral economic research suggests that elevated demand reflects stronger and more persistent motivation to consume the substance (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008), and the present results suggest that there is meaningful variability in demand even among heavy drinkers. Thus, the present results may help to explain the elevated risk for alcohol problems and poor treatment response observed among drinkers with depression or PTSD (Geisner et al., 2007; Hien et al., 2000; Kaysen et al., 2007). Student drinkers with elevated symptoms of depression or PTSD may resist changing their level of consumption in the face of increasing price contingencies more so than other students (Rousseau et al., 2011), perhaps suggesting that the negatively reinforcing properties of alcohol are more salient than the response cost associated with excess drinking. In addition to the potential for negatively reinforced drinking, it is also possible that drinkers with symptoms of PTSD or depression, both of which are often associated with social deficits, are especially reliant on alcohol as a means of social facilitation (Cooper et al., 1995; Kirchner et al., 2006; Read et al., 2003). PTSD and depression are also characterized by myopia (Dalgleish et al., 1997; Gonzalez et al., 2011), which may lower the influence of future economic considerations (e.g., savings, credit card bills) on drinking decisions.

Although the present study used monetary price contingencies, behavioral economic theory defines price broadly to include the overall response cost associated with drug acquisition (DeGrandpre and Bickel, 1996; Murphy et al., 2007). This includes the monetary price of drinks as well as nonmonetary elements of response cost such as the effort required to obtain alcohol and probabilistic risks associated with drinking (e.g., potential for alcohol-related citations or arrests, accidents or injuries, hangovers, missed class, lower grades, long term-health effects and/or dependence). Future prospective research is needed to investigate the possibility that the lack of sensitivity to monetary price contingencies evidenced by drinkers with symptoms of depression or PTSD may reflect a more general lack of sensitivity to the escalating psychosocial and health costs associated with drinking. If so, this would suggest that drinkers with negative affect might be less likely to reduce their drinking when faced with these adverse outcomes or costs (Costanzo et al., 2007; Geisner et al., 2007). Indeed, previous research indicates that elevated demand is associated with poor response to a brief motivational intervention that attempts to highlight the costs of heavy drinking (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007). This sample included a large number of students who were under age 21 and may drink primarily at college parties where alcohol is often free or inexpensive. Should their relatively inelastic demand persist after they turn 21 and they begin to drink in restaurant and bar settings, they may be at elevated risk for persistent or increased drinking even in the face of greater drink prices. Similarly, students with symptoms of depression or PTSD may be less sensitive to prevention efforts that are aimed at increasing drink price (e.g., eliminating drink specials and access to low cost alcohol; Toomey et al., 2007).

Although future research is needed to determine the specific implications of these indices on patterns of drinking over time, high demand intensity may reflect a greater relative risk for negative consequences associated with extreme consumption. Students with elevated symptoms of depression or PTSD symptoms may be at especially high risk in situations where large quantities of alcohol are available at very low prices, such as at keg parties or other occasions where the drinker does not have to purchase his or her drinks (e.g., 21st birthday or other celebrations where friends may purchase drinks; Lewis et al., 2009). Thus it may be particularly important for college drinkers who have co-occurring mood-related symptoms to avoid this type of drinking occasion, or to implement moderation strategies (Neighbors et al., 2009). Elevated demand on the variables related to expenditures and price sensitivity (breakpoint, Pmax, Omax, and elasticity) may not be associated with acute risk for harm, but it may suggests a willingness to spend large quantities of money on alcohol, and research with adult problem drinkers suggests that excessive relative monetary allocations towards alcohol may predict a more chronic and severe pattern of drinking (Tucker et al., 2002; 2009).

This study has several relevant limitations, including the cross-sectional design. Future longitudinal research is needed to establish a more conclusive causal model of mood, alcohol demand, and patterns of drinking over time. Additionally, although we used well-validated measures, future research should consider the use of interview based measures of depression and PTSD diagnosis, and measures of alcohol demand based on actual consumption and expenditures obtained in laboratory or naturalistic setting. Another limitation is that we were unable to compute elasticity values for 40 participants due to poor curve fits. These were primarily relatively lighter drinkers who did not report enough non-zero consumption values on the APT to generate a good curve fit. Although their other demand metric values were valid, future research should consider including more low-price values on the APT in order to increase curve fits with relatively lighter drinkers. Finally, the sample was limited to students who were recruited from a single university and who reported heavy drinking within the past month.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide a conceptual and empirical bridge between the behavioral economic and the alcohol-mood disorder comorbidity literatures and suggest that symptoms of depression and PTSD may contribute to an overvaluation of alcohol rewards in high-risk young adult drinkers. The fact that PTSD symptoms showed a more robust pattern of associations with the demand metrics is consistent with previous research indicating that PTSD may pose greater risk for substance misuse than other forms of psychopathology (McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2010; Ouimette et al., 1998) and suggests that young adult drinkers with PTSD symptoms are an especially high risk population. These findings also provide support for behavioral economic models of addiction that stress the importance of visceral states such as negative affect in the over-valuation of drug rewards (Laibson, 2001; Lowenstein, 2007).

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source (mandatory)

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the Alcohol Research Foundation (ABMRF) to Murphy. The ABMRF had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors (mandatory)

Authors Murphy, MacKillop, Martens, and McDevitt-Murphy designed the study. Authors Dennhardt, Skidmore, and Yurasek undertook the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest (mandatory)

All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment Spring. Reference Group Data Report (Abridged), 2009. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2008;57:477–488. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.5.477-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Acker J, Stojek MK, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Is talk “Cheap”? An initial investigation of the equivalence of Alcohol Purchase Task Performance for Hypothetical and Actual Rewards. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36:716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariely D, Loewenstein G, Prelec D. Coherent arbitrariness: stable demand curves without stable preferences. In: Loewenstein G, editor. Exotic Preferences: Behavioral Economics and Human Motivation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 282–313. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Cabrera O, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 2008;76:272–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EB, Smith SR, Palmieri PA, Dalenberg C, Ruzek JI, Kimerling R, Burling TA, Spain DA. Development and validation of a brief self-report measure of trauma exposure: the Trauma History Screen. Psychol. Asses. 2011;23:463–477. doi: 10.1037/a0022294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Ankera JJ, Perry JL. Modeling risk factors for nicotine and other drug abuse in the preclinical laboratory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:S70–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Stout RL, Mueller T. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse relapse among women: a pilot study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1996;10:124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CM, Demb A. College high risk drinkers: who matures out? And who persists as adults? J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2008;52:19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Correia CJ, Benson TA, Carey KB. Decreased substance use following increases in alternative behaviors: a preliminary investigation. Addict. Behav. 2005;30:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo PR, Malone PS, Belsky D, Kertesz S, Pletcher M, Sloan FA. Longitudinal differences in alcohol use in early adulthood. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:727–737. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T, Taghavi R, Neshat-Doost H, Moradi A, Yule W, Canterbury R. Information processing in clinically depressed and anxious children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1997;38:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Psychopathology associated with drinking and alcohol use disorders in the college and general adult populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK. Drug dependence as consumer demand. In: Green L, Kagel JH, Green L, Kagel JH, editors. Advances in Behavioral Economics, Vol. 3: Substance Use and Abuse. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing; 1996. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011;25:595–604. doi: 10.1037/a0025807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Dunham DN, Ries A, Barnett J. Symptoms of traumatic stress and substance use in a non-clinical sample of young adults. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:2094–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Few L, Acker J, Murphy C, Mackillop J. Stability of a cigarette purchase task. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr222. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner I, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addict. Behav. 2004;29:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner I, Neighbors C, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Evaluating personal alcohol feedback as a selective prevention for college students with depressed mood. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:2776–2787. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez V, Reynolds B, Skewes M. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011;19:303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0022720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RR, Rush CR, Puhala KA. Validation of the multiple-choice procedure for investigating drug reinforcement in humans. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1996;4:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Nunes E, Levin FR, Fraser D. Posttraumatic stress disorder and short-term outcome in early methadone treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2000;19:31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW. Magnitude and prevention of college drinking and related problems. Alcohol Res. Health. 2010;33:45–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman E. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: changes from 1998 to 2005. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S, Heil S, Lussier J. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2004;55:431–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol. Rev. 2008;115:186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Alcohol use disorders and psychological distress: a prospective state-trait analysis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003;112:599–613. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Bickel WK. Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:412–426. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10-year follow-up study. Am. J. Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:659–84. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Replacing relative reinforcing efficacy with behavioral economic demand curves. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2006;85:73–93. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.102-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Dalgleish T, Thrasher S, Yule W. Impulsivity and post-traumatic stress. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1997;22:279–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, Sayette MA, Cohn JF, Moreland RL, Levine JM. Effects of alcohol on group formation among male social drinkers. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006;67:785–793. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, Olaman S. Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997;35:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laibson DI. A cue-theory of consumption. Q. J. Econ. 2001;116:81–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Lindgren KP, Fossos N, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L. Examining the relationship between typical drinking behavior and 21st birthday drinking behavior among college students: implications for event-specific prevention. Addiction. 2009;104:760–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010;119:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G. A visceral account of addiction. In: Elster J, Skog OJ, editors. Getting Hooked: Rationality and Addiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 188–213. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G. Exotic Preferences: Behavioral Economics and Human Motivation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Brown C, Murphy C, Stojek M, Sweet L, Niaura R. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-and withdrawal-elicited craving for tobacco: an initial study. Nicotine Tob. Res. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010a;119:106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, O’Hagen S, Lisman SA, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Tidey JW, McGeary JE, Monti PM. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for alcohol. Addiction. 2010b;105:1599–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J, Murphy J. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy J, Tidey J, Kahler C, Ray L, Bickel W. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Tidey J. Cigarette demand and delayed reward discounting in nicotine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia and controls: an initial study. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2185-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden G, Bickel W, editors. Impulsivity: The Behavioral and Neurological Science of Discounting. Washington, DC: APA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG, Monahan CJ, Flood AM, Weathers FW. Unique patterns of substance misuse associated with PTSD, depression, and social phobia. J. Dual Diag. 2010;6:94–110. doi: 10.1080/15504261003701445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Williams JL, Bracken KL, Fields JA, Monahan CJ, Murphy JG. PTSD symptoms, hazardous drinking, and health functioning among U.S. OEF and OIF veterans presenting to primary care. J. Trauma Stress. 2010;23:108–111. doi: 10.1002/jts.20482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Computerized versus motivational interviewing alcohol interventions: impact on discrepancy, motivation, and drinking. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2010;24:628–639. doi: 10.1037/a0021347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Skidmore JR, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM. A behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Addict. Res. Theory. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2012.665965. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T. Internet-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st birthday drinking: a randomized controlled trial of an Event Specific Prevention Intervention. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009;77:51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0014386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Brown PJ, Najavits LM. Course and treatment of patients with both substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addict. Behav. 1998;23:785–795. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrelli P, Farabaugh AH, Zisook S, Tucker D, Rooney K, Katz J, Clain AJ, Petersen TJ, Fava M. Gender,depressive symptoms and patterns of alcohol use among college students. Psychopathology. 2011;44:27–33. doi: 10.1159/000315358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimberling R, Cameron RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Prim. Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Reframing Health Behavior Change with Behavioral Economics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. The Lonely Addict. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Schiffbauer R. Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: an experiential discounting task. Behav. Proc. 2004;67:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau GS, Irons JG, Correia CJ. The reinforcing value of alcohol in a drinking to cope paradigm. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Responses to smoking cues are relevant to smoking and relapse. Addiction. 2009;104:1617–1618. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG. The effect of drink price and next-day responsibilities on college student drinking: a behavioral economic analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2010;25:57–68. doi: 10.1037/a0021118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Martens MM, Murphy JG, Buscemi J, Yurasek AM, Skidmore JR. Reinforcing efficacy moderates the relationship between impulsivity-related traits and alcohol use. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:521–529. doi: 10.1037/a0021585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Wray J. The continuing conundrum of craving. Addiction. 2009;104:1618–1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Lenk KM, Wagenaar AC. Environmental policies to reduce college drinking: an update of research findings. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:208–219. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Roth DL, Vignolo MJ, Westfall AO. A behavioral economic reward index predicts drinking resolutions: moderation revisited and compared with other outcomes. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009;77:219–228. doi: 10.1037/a0014968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Rippens PD. Predicting natural resolution of alcohol-related problems: a prospective behavioral economic analysis. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:248–257. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich R, Heather N. Choice, Behavioural Economics And Addiction. Amsterdam Netherlands: Pergamon/Elsevier Science Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004;192:269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasek AM, Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Buscemi J, McCausland C, Marten MP. Drinking motives mediate the relationship between reinforcing efficacy and alcohol consumption and problems. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2011;73:991–999. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]