Abstract

New approaches that allow precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression in model organisms at the single cell level are necessary to better dissect the role of specific genes and cell populations in development, disease and therapy. Here, we describe a new optochemogenetic switch (OCG switch) to control CreER/loxP-mediated recombination via photoactivatable (“caged”) tamoxifen analogues in individual cells in cell culture, organoid culture and in vivo in adult mice. This approach opens opportunities to more fully exploit existing CreER transgenic mouse strains to achieve more precise temporal- and location-specific regulation of genetic events and gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

Site-specific recombination mediated by Cre recombinase is a powerful genetic tool to manipulate genetic elements in model organisms.1 When placed under the control of a tissue-specific promoter, Cre/LoxP-mediated recombination allows tissue-specific investigation of gene functions.1 Fusing Cre with a mutant form of the estrogen receptor (ER) ligand binding domain further enables temporal control of recombination.1 While this conditional CreER system allows for temporal control, the spatial control through tissue-specific promoters is limited by relatively broad activation in all target cells, non-specificity of many of such cell type-‘specific’ promoters and/or the lack of validated promoters in certain cell types. We argue, that to better dissect the roles of different cell populations within tissues and organs, it would be highly desirable to develop methods that allow cell rather than tissue- specific gene activation.

The prerequisite for selectively modulating biological function at a cellular level is the use of activation tools that can be confined to a cellular or even sub-cellular volume. Light can be used as an external orthogonal stimulus to activate biological functions in a spatiotemporally controlled fashion.2, 3 Light can furthermore be manipulated in a very precise manner to achieve activation of groups of cells or even individual cells in spatially defined regions of interest. Photochemical control of protein functions has been achieved through a variety of approaches, including caged small molecules, installation of caging groups or photo-switchable groups on the proteins, or fusion with photoactivatable protein domains.4 A general method for creating photoactivatable caging systems is to first mask the activity of the biologically active substance through attachment of a photo-labile protecting group, termed “caging group”. Light then can be used to remove this caging group to activate and restore the native biological activity of the parent compound.5,6,7 This approach has been applied to address various biological questions regarding cellular signaling pathways and neurological processes.6,8,9,10

Several approaches have been developed to render Cre-mediated recombination inducible by light. One study showed that Cre activity can be photoregulated by caging the critical residue Tyr324 in the protein structure.11 However, the in vivo application of the method would require the generation of new Cre mutant animals. Alternatively, certain small molecule ER antagonists (tamoxifen and its derivatives) can be caged and photoreleased to control CreER activity. The feasibility of these approaches has been demonstrated in cell culture systems and the zebrafish model.12,13,14,15 However, it is currently unknown whether caged tamoxifen analogues would work reliably in CreER transgenic mice where pharmacokinetics of caged drugs, delivery barriers and complex light/tissue interactions are formidable obstacles. To address this question, we synthesized a caged tamoxifen analogue and applied the compound to a series of in vitro and in vivo photoactivation experiments to investigate whether it could reliably induce efficient light-dependent Cre-mediated recombination in mice. We confirmed the activity of this photochemogenetic (OCG) switch and suggest its application may significantly improve the current methods of modeling human diseases in mice where the CreER technology is employed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and instruments

Unless otherwise stated, all the reagents for the synthesis of caged 4-OHC were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and used as received. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400 MHz spectrometer. High performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) analysis was performed on a Waters (Milford, MA) LC-MS system. In the LC-MS system, electrospray ionization (ESI) was used to obtain mass spectrometry. A Waters XTerra C18 5 μm column was used for HPLC-MS analysis (eluents: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (v/v) in water and acetonitrile; gradient: 0–9.5 min, 5–100% B; 9.5–10.0 min 100% B). The chromatograms were processed using MassLynx software (from Waters). UV-Vis spectra were recorded in a TECAN microplate reader. A 6W hand held UV lamp (UVP, LLC) was used for uncaging the caged 4-OHC both in vitro and in vivo.

Mice

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee. Homozygous Rosa26CreERT2, mT/mG, and R26R mice in C57BL/6 background were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock Number: 8463, 7676 and 3474, respectively). Heterozygous Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG and Rosa26CreERT2;R26R mice were generated by crossing the homozygous mice and which were then used throughout the study.

Synthesis of caged 4-OHC

The DMNPE caging group and 4-OHC were synthesized by following a previously described procedure.14,27 1-(4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl)ethyl (DMNPE) moiety was conjugated to 4-OHC under Mitsonobu coupling conditions. Briefly, in a 25 ml round bottom flask, DMNPE (0.014 g, 0.063 mmol), 4-OHC (0.020 g, 0.057 mmol) and triphenyl phosphine (PPh3, 0.016 g, 0.063 mmol) were mixed together in 0.5 ml of tetrahydrofuran (THF) under an argon atmosphere. After stirring the solution at room temperature (RT) for ~5 min, diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD, 0.012 ml, 0.063 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at RT for ~ 2.5 h. The crude product was directly charged to a SiO2 column for purification (eluent: 100% dichloromethane to 10% methanol in dichloromethane v/v). Caged 4-OHC was isolated as a yellow solid. Yield = 31%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 6.93 (m, 4H), 6.79 (d, 2J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.67 (d, 2J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.10 (q, 4J = 6.13 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (t, 3J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 2.72 (t, 3J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 2.35 (s, 6H), 2.18 (m, 4H), 1.67 (d, 2J = 6 Hz, 3H), 1.56 (m, 6H). MS (electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: ESI-MS) calculated: 560.29, found: 561.40 [M+H]+.

UV-Vis and HPLC-MS characterization of the photocleavage of caged 4-OHC

A 0.25 mM solution of caged 4-OHC in 1:1 (v/v) water:acetonitrile was used for the UV-Vis spectroscopic characterization of the photocleavage reaction. The solution of the caged 4-OHC was placed in a 96 well black clear bottom microplate. The solution was then irradiated at ~365 nm using a hand held UV lamp. After light exposure, UV-Vis spectra of the solution were recorded in a TECAN microplate reader. Time course of the photocleavage reaction was monitored by exposing the caged 4-OHC solution to light for different durations, and subsequently recording the UV-Vis spectra of the solution. A 2.0 mM solution of caged 4-OHC in 1:1 (v/v) water:acetonitrile was used for the HPLC-MS study. The solution of the caged 4-OHC was placed in a glass vial and irradiated at ~365 nm using a hand held UV lamp. Aliquots were taken at different time intervals and injected to the HPLC-MS machine for analysis. Prism 5 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) for Mac was used to plot the data.

MEF isolation and photoactivation procedure

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were isolated from embryos of the cross between homozygous Rosa26CreERT2 and homozygous mT/mG (or R26R) following previously described protocol28 and grown in DMEM with 10% FBS. To illuminate UV light on the cells, the cells were first grown in 60 mm dish overnight to become nearly confluent. Next day, the medium was replaced with medium containing caged 4-OHC at 5μM and incubated for 30min. The cells were washed twice quickly with warm PBS and covered with fresh medium. The dish was placed on the UV emission surface of a handheld 6W Long-wavelength UV lamp (UVP, LLC), and UV light was kept on for designated period of time. The cells were returned to the incubator to culture for 48–72h before live imaging or flow cytometric analysis.

Mammary 3D culture and photoactivation procedure

Mouse mammary epithelial cells were isolated from 6–8 week old female Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice as previously described.29 Briefly, mammary glands were excised, minced using scalpels, and digested for 1hr in 300U/ml type 1A collagenase (Sigma) and 100U/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma). Cells were then treated with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA, dispase (Invitrogen)/DNase (Sigma), and ACK lysing buffer (Invitrogen) in succession. Between each treatment, cells were rinsed in MEGM (1:1 DMEM:F12 Ham supplemented with 5mg/ml insulin, 500ng/ml hydrocortisone, 10ng/ml EGF, 20ng/ml cholera toxin, 5% bovine calf serum, and 1X penicillin/streptomycin). Afterwards, cells were filtered twice through 40mm nylon cell strainers and seeded in 35mm dishes that contained a layer of Growth factor Reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) measuring approximately 1–2 mm thickness. Acini usually formed in 4–8 days. During photoactivation, the acini were incubated with MEGM containing 5μM caged 4-OHC for 1hour. The cells were washed twice quickly with warm PBS and covered with fresh medium. The dish was placed on the UV emission surface of a handheld 6W Long-wavelength UV lamp (UVP, LLC, exposure time: 1min) or above the 60X objective of an inverted epifluorescent microscope equipped with a standard DAPI filter set. The cells were returned to the incubator to culture for >48h before live cell imaging using an upright Zeiss 710 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 20x and 40x water immersion objectives.

Photoactivation procedure in mice

Female mice of 6–8 week old were clean shaven on the dorsal and ventral sides. The caged 4-OHC was dissolved in 20% Solutol for in vivo delivery. The vehicle or 1mg caged 4-OHC in vehicle were injected intraperitoneally. One hour later, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and exposed to UV light from the handheld 6W Long-wavelength UV lamp (UVP, LLC) for 15min. Alternatively, for mammary tissue illumination, the right inguinal (#4) mammary fat pad was exposed by creating a small skin flap and illuminated with UV light for 15min. For enhanced photoconversion, this procedure was repeated four times. On the seventh day, the mice were imaged with Olympus OV-110 epifluorescence imager to detect fluorescent signals emitted from the skin on the dorsal and ventral sides. Alternatively, the left and right mammary glands were dissected and immediately imaged using the intravital laser scanning microscope IV-110.

RESULTS

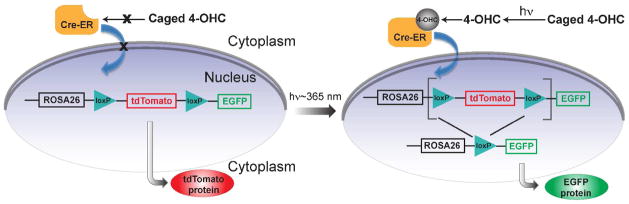

To design a biological system that can faithfully report on the induced activity of CreER, we took advantage of a recently developed double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse, the mT/mG strain,16 which expresses tdTomato prior to, and EGFP following Cre-mediated recombination ubiquitously in tissues. The homozygous mT/mG mouse was crossed to the homozygous Rosa26CreERT2 strain,17 and the progenies, Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG, were heterozygous for both alleles. We reasoned that by illuminating cells and tissues from these mice with UV light and looking for EGFP-expressed cells, we would be able to test the photoinduced activity of caged tamoxifen analogues (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematics showing the photoactivation-dependent CreER/loxP system in the Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG reporter mice. To produce a light-sensitive CreER/loxP system, 4-OHC was modified with a light sensitive caging group to inhibit its ability to induce CreER-mediated recombination. Photoactivated release of 4-OHC induces EGFP gene expression in illuminated cells.

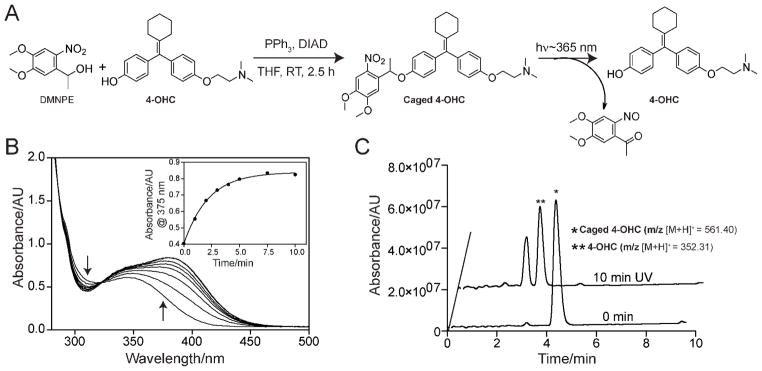

We used the 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) analogue, 4-hydroxycyclofen (4-OHC) as a small molecule agonist of the ER component of the fusion protein. Although 4-OHT and 4-OHC have similar binding affinity to the ER, 4-OHC is preferred over 4-OHT in view of its synthetic accessibility and better photostability.14 As shown in Figure 2A, 4-OHC was caged by attaching a photolabile 1-(4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl)ethyl (DMNPE) moiety to the free hydroxy group of 4-OHC using the Mitsonobu reaction.14 Under ambient light, the DMNPE caging group is stable in physiological conditions. However, exposure to longwavelength UV irradiation (~ 350–410 nm with a peak at 365 nm) leads to photolytic cleavage, releasing 4-OHC (Figure 2A). The photocleavage reaction of the caged 4-OHC was monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy. A change in UV-Vis absorption spectrum was observed when a solution of caged 4-OHC was exposed to a handheld 365 nm UV lamp and was typical of the breakage of DMNPE caging group (Figure 2B). The photochemical reaction was complete within 10 min of exposure (inset of Figure 2B). High performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) verified the chemical identity of the photoreleased products and also confirmed quantitative, unidirectional conversion to 4-OHC (Figure 2C). Overall, these characterizations indicate that the caged 4-OHC undergoes efficient photocleavage at 365 nm UV light and releases 4-OHC.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of caged 4-OHC and photocleavage characterization. (A) Synthesis of caged 4-OHC under Mitsonobu reaction condition and activation (uncaging) of caged 4-OHC using 365 nm UV light. (B) Changes in UV-Vis absorbance during the photocleavage of caged 4-OHC in water:acetonitrile (1:1 v/v). Inset shows the change in absorbance at 375 nm over UV irradiation time. Note that the photocleavage is complete within 10 min of irradiation. (C) HPLC-MS chromatograms showing the quantitative formation 4-OHC from caged 4-OHC upon UV irradiation. Caged 4-OHC solutions, before (0 min) and after light exposure (10 min UV), were analyzed by HPLC-MS. Formation of 4-OHC was identified by the appearance of molecular mass corresponding to 4-OHC (m/z 352.31 [M+H]+). The peak other than the 4-OHC appeared in the 10 min UV chromatogram belongs to the cleaved caging group (see Figure 2A for the photocleavage reaction).

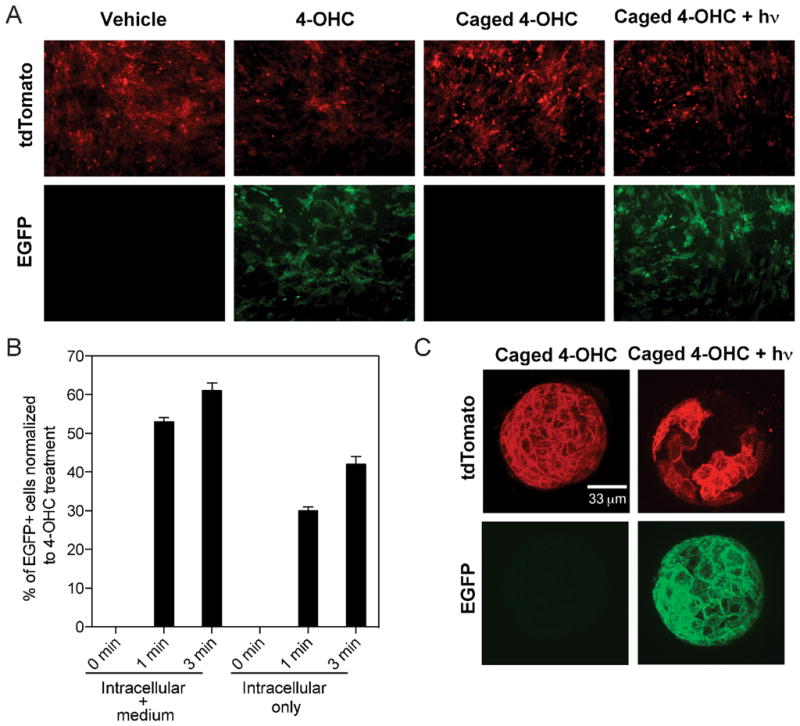

To test the caged 4-OHC activity, we started with a simple biological system, the mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from the Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice in cell culture conditions. Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG MEFs were treated with either 4-OHC or caged 4-OHC and illuminated at 365 nm. As expected, photocleavage of the caged 4-OHC induced EGFP expression in a stringent fashion (Figure 3A–B). To provide an independent tester for the compound, we generated another reporter mouse, Rosa26CreERT2;R26R by crossing homozygous Rosa26CreERT2 with homozygous Rosa26-loxP-STOP-loxP-lacZ mice18 (Figure S1A). Similar results were observed in the Rosa26CreERT2;R26R MEFs (Figure S1B). We did not observe any major phototoxicity or cell viability changes due to the UV irradiation in our experiments (energy density 1.6 mW/cm2, photon energy 3.4 eV, number of photons per second per cm2 2×1015, up to 3 min exposure time), consistent with other reports.5,19

Figure 3.

Photoactivation of caged 4-OHC in vitro. (A) Induction of EGFP expression by 365 nm UV activation of caged 4-OHC in MEFs isolated from Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG embryos. (B) Flow cytometric quantification of EGFP+ MEF cells upon treatment with 4-OHC and caged 4-OHC under different durations of UV activation. The ‘Intracellular + medium” group represents cell samples without PBS wash before UV irradiation, whereas the ‘Intracellular only’ group represents cell samples washed twice with PBS before UV irradiation. Data represent mean ± SD. (C) EGFP expression induced by 365 nm UV activation of caged 4-OHC in mammary epithelial cells isolated from Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG female mice and cultured to form acini on Matrigel. All acini grown on the dish were illuminated in a uniform manner to induce EGFP expression. Images shown are projections of the Z-stack confocal images.

While a convenient system, the 2D cell culture cannot manifest all the biological responses of cells to external perturbations in a 3D environment. Therefore, we went on to test whether caged 4-OHC would enable light-dependent Cre-mediated recombination in a well established organoid model, the mammary acinus culture.20 Mammary epithelial cells from Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice were isolated and overlaid on a basement membrane to allow polarized acinar structure development. The formed acini were subjected to caged 4-OHC treatment with or without subsequent brief UV illumination by the UV lamp (energy density 1.6 mW/cm2, photon energy 3.4 eV, number of photons per second per cm2 2×1015, 1 min exposure time) (Figure 3C and Video S1–2) or the 60X objective of an inverted fluorescent microscope equipped with a standard DAPI filter set (Figure S2 and Video S3–4). Similar to 2D culture results, the caged 4-OHC allowed very tight control of EGFP expression in response to photoactivation.

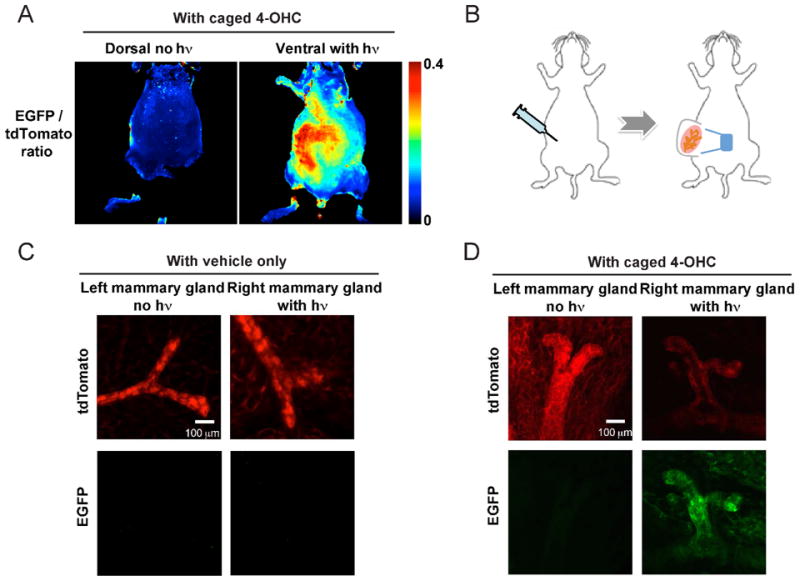

Finally and most importantly, we demonstrated that caged 4-OHC was able to induce gene activation in vivo in mice upon photoactivation. We focused on two organs, skin and mammary glands, given their ease of imaging, accessibility to light and breadth of different cell populations. We used a custom-built broad illumination method for in vivo testing. We first monitored EGFP/tdTomato expression at the whole mouse level using the Olympus OV-110 epifluorescence imager.21 Very low green autofluorescence was detected in Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice when treated with vehicle control and irradiated with 365 nm UV, and strong EGFP signal was detected when treated with 4-OHC (Figure S3). In the test experiment, Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice were injected intraperitoneally with caged 4-OHC and subjected to UV illumination only on the ventral (but not dorsal) skin. Resultant EGFP signal was observed on the ventral skin but not on the dorsal skin (Figure 4A) with an average 2.5-fold increase in fluorescence intensity. Because the increase of the EGFP signal was concomitant with the decrease of the tdTomato signal, EGFP/tdTomato ratios were presented in Figure 4A for both ventral and dorsal skin.

Figure 4.

Photoactivation of caged 4-OHC in vivo. (A) Strong induction in EGFP expression on the ventral skin as a result of 365 nm UV illumination of the Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice injected with caged 4-OHC. The dorsal skin was not illuminated and showed little EGFP signal. An increase in EGFP signal is followed by a decrease of tdTomato signal; low values of EGFP/tdTomato ratio correspond to low EGFP and high tdTomato, while high values of ratios correspond to high EGFP and low tdTomato. (B) Experimental design for intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or caged 4-OHC into the Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG female mice and subsequent 365 nm illumination on the right inguinal (#4) mammary fat pad. (C–D) The results of experiments in (B) with mammary tissue ex vivo imaged with IV-110. Only the right illuminated mammary gland from the mouse injected with caged 4-OHC expressed EGFP.

We next tested the OCG switch on mammary glands of the female Rosa26CreERT2;mT/mG mice. The mice were injected with vehicle or caged 4-OHC, and only the right mammary gland was exposed to the 365 nm light whereas the left was not (Figure 4B). Seven days later, the right and left mammary glands were resected for ex vivo imaging at a high spatial resolution using the Olympus Intravital Laser Scanning Microscope IV-110.22 We first confirmed that 365 nm UV illumination of the mammary gland alone did not cause noticeable green autofluorescence increase or tissue morphological changes (Figure 4C). However, when caged 4-OHC was injected, the right, but not the left, mammary gland showed strong EGFP induction (Figure 4D). Taken together, the skin and mammary gland data clearly establish that the caged 4-OHC displayed superior in vivo inducibility by light and limited diffusion after uncaging to affect other organs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that caged 4-OHC can efficiently regulate CreER-mediated recombination in a light-dependent manner not only in cell culture but also in adult mice. While caged 4-OHT analogues were shown to control CreER-mediated gene expression in response to photoactivation in cell culture12 and zebrafish,14, 15 our results demonstrate this approach can indeed be applied to adult mice to induce localized gene activation as a function of light illumination.

Photoregulation of protein activity can be achieved through either photo-uncaging as shown in this study, or using genetically engineered light-gated modules,2 for example, split Cre recombinase fused to light-dependent dimerization partners CRY2 and CIBN.23 One major advantage of using caged 4-OHC over other methods of making Cre activity photoregulatable is that one can seamlessly integrate the technology into numerous existing CreER mouse strains to achieve an additional level of stringent control, i.e., regional and cell specific control of gene expression. This is of particular interest if the investigated biological questions require photoregulatable Cre activity in a mammalian model organism and can be studied based on existing CreER strains, because constructing new mouse strains possessing the necessary light-gated modules will be a lengthy and costly process. For example, the villin-CreERT2 mouse allows efficient target gene recombination throughout the entire digestive epithelium in response to systemic tamoxifen treatment,24 and by restricting light activation of caged 4-OHC to the colon, this mouse strain may become an excellent driver for spatiotemporal modeling of colorectal cancer in mice.

The application of the OCG switch is not confined to CreER; instead, it should provide photoregulation of a spectrum of ER-fusion proteins. These proteins were fused with ER to allow tamoxifen-dependent control of nuclear localization and protein activity.25 For example, using the ER-fusion approach, we recently reported the marked reversal of systemic degenerative phenotypes in aged telomerase-deficient TERT-ER mice by tamoxifen treatment and telomerase reactivation.26 It will be interesting to apply the OCG switch to this system to determine the contribution of each organ system to the phenotypic reversal.

In summary, we foresee the described OCG switch approach to find broad applications, especially in tumor and developmental biology, where localized and pattern-specific gene manipulation is of central importance to address many outstanding questions. We believe that this approach could likewise be applied to spatiotemporally controlled gene activation in internal organs by employing UV light guided through an optical fiber. Alternatively, two-photon activation can be used to somewhat increase the tissue penetration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rujuta Narurkar, Emma Labrot, Eliot Fletcher-Sananikone, Zhou Shan, Shan Jiang for assistance in the animal facility. We thank Y. Alan Wang and other colleagues in our laboratories for helpful advice and discussion. We thank Joshua Dunham, Alex Zaltsman and Lisa Cameron for help with imaging. This work was supported in part by grants PO1CA117969 (R.A.D.), U01CA141508 (R.A.D.), P50-CA86355 (R.W.), U24CA092782 (R.W.). X.L. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund. S.S.A. is supported by an NIH fellowship (HHSN268201000044C).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supporting figures and videos. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Nagy A. Cre recombinase: the universal reagent for genome tailoring. Genesis. 2000;26:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toettcher JE, Voigt CA, Weiner OD, Lim WA. The promise of optogenetics in cell biology: interrogating molecular circuits in space and time. Nat Methods. 2011;8:35–38. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agasti SS, Chompoosor A, You CC, Ghosh P, Kim CK, Rotello VM. Photoregulated release of caged anticancer drugs from gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5728–5729. doi: 10.1021/ja900591t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riggsbee CW, Deiters A. Recent advances in the photochemical control of protein function. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young DD, Deiters A. Photochemical control of biological processes. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:999–1005. doi: 10.1039/b616410m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis-Davies GC. Caged compounds: photorelease technology for control of cellular chemistry and physiology. Nat Methods. 2007;4:619–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer G, Heckel A. Biologically active molecules with a “light switch”. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:4900–4921. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaway EM, Katz LC. Photostimulation using caged glutamate reveals functional circuitry in living brain slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7661–7665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis-Davies GC, Kaplan JH. Nitrophenyl-EGTA, a photolabile chelator that selectively binds Ca2+ with high affinity and releases it rapidly upon photolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:187–191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis-Davies GC. Neurobiology with caged calcium. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1603–1613. doi: 10.1021/cr078210i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards WF, Young DD, Deiters A. Light-activated Cre recombinase as a tool for the spatial and temporal control of gene function in mammalian cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:441–445. doi: 10.1021/cb900041s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Link KH, Shi Y, Koh JT. Light activated recombination. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13088–13089. doi: 10.1021/ja0531226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y, Koh JT. Light-activated transcription and repression by using photocaged SERMs. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:788–796. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinha DK, Neveu P, Gagey N, Aujard I, Benbrahim-Bouzidi C, Le Saux T, Rampon C, Gauron C, Goetz B, Dubruille S, Baaden M, Volovitch M, Bensimon D, Vriz S, Jullien L. Photocontrol of protein activity in cultured cells and zebrafish with one- and two-photon illumination. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:653–663. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha DK, Neveu P, Gagey N, Aujard I, Le Saux T, Rampon C, Gauron C, Kawakami K, Leucht C, Bally-Cuif L, Volovitch M, Bensimon D, Jullien L, Vriz S. Photoactivation of the CreER T2 recombinase for conditional site-specific recombination with high spatiotemporal resolution. Zebrafish. 2010;7:199–204. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2009.0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cambridge SB, Geissler D, Calegari F, Anastassiadis K, Hasan MT, Stewart AF, Huttner WB, Hagen V, Bonhoeffer T. Doxycycline-dependent photoactivated gene expression in eukaryotic systems. Nat Methods. 2009;6:527–531. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurber GM, Figueiredo JL, Weissleder R. Multicolor fluorescent intravital live microscopy (FILM) for surgical tumor resection in a mouse xenograft model. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly KA, Bardeesy N, Anbazhagan R, Gurumurthy S, Berger J, Alencar H, Depinho RA, Mahmood U, Weissleder R. Targeted nanoparticles for imaging incipient pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy MJ, Hughes RM, Peteya LA, Schwartz JW, Ehlers MD, Tucker CL. Rapid blue-light-mediated induction of protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:973–975. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.el Marjou F, Janssen KP, Chang BH, Li M, Hindie V, Chan L, Louvard D, Chambon P, Metzger D, Robine S. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis. 2004;39:186–193. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Dyke T, Jacks T. Cancer modeling in the modern era: progress and challenges. Cell. 2002;108:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaskelioff M, Muller FL, Paik JH, Thomas E, Jiang S, Adams AC, Sahin E, Kost-Alimova M, Protopopov A, Cadinanos J, Horner JW, Maratos-Flier E, Depinho RA. Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;469:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature09603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyer RG, Turnbull KD. Hydrolytic Stabilization of Protected p-Hydroxybenzyl Halides Designed as Latent Quinone Methide Precursors. J Org Chem. 1999;64:7988–7995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharpless NE, Ferguson DO, O’Hagan RC, Castrillon DH, Lee C, Farazi PA, Alson S, Fleming J, Morton CC, Frank K, Chin L, Alt FW, DePinho RA. Impaired nonhomologous end-joining provokes soft tissue sarcomas harboring chromosomal translocations, amplifications, and deletions. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiede BJ, Owens LA, Li F, DeCoste C, Kang Y. A novel mouse model for non-invasive single marker tracking of mammary stem cells in vivo reveals stem cell dynamics throughout pregnancy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.