Abstract

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) control many cellular processes and have been implicated in the regulation of left-right (LR) development by as yet unknown mechanisms. Using lineage-targeted knockdowns, we found that the transmembrane HSPG Syndecan 2 (Sdc2) regulates LR patterning through cell-autonomous functions in the zebrafish ciliated organ of asymmetry, Kupffer’s vesicle (KV), including regulation of cell proliferation and adhesion, cilia length and asymmetric fluid flow. Exploring downstream pathways, we found that the cell signaling ligand Fgf2 is exclusively expressed in KV cell lineages, and is dependent on Sdc2 and the transcription factor Tbx16. Strikingly, Fgf2 controls KV morphogenesis but not KV cilia length, and KV morphogenesis in sdc2 morphants can be rescued by expression of fgf2 mRNA. Through an Fgf2-independent pathway, Sdc2 and Tbx16 also control KV ciliogenesis. Our results uncover a novel Sdc2-Tbx16-Fgf2 pathway that regulates epithelial cell morphogenesis.

Keywords: Fgf2, Kupffer’s vesicle, Left-right patterning, Syndecan 2, Spadetail

INTRODUCTION

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) comprise a core protein with covalently attached heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (HS-GAGs) (Carey, 1997; Kramer and Yost, 2003). HS-GAGs interact with many ligands, making it possible for HSPGs to function in a wide variety of processes such as cell migration, cell adhesion, cell signaling and extracellular matrix and cytoskeletal organization (Carey, 1997). Syndecan 2 (Sdc2) is a member of a highly conserved family of single-pass transmembrane HSPGs (Carey, 1997; Couchman, 2003; Multhaupt et al., 2009). Sdc2 can physically interact with members of the FGF, VEGF and TGFβ superfamilies (Chen et al., 2004a; Chen et al., 2004b; Villena et al., 2003). In cell culture, Sdc2 has been implicated in tumorigenesis and microvascular angiogenesis through regulation of cell adhesion and cell migration (Fears et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009; Noguer et al., 2009).

Although the syndecan family was discovered many years ago (Bernfield et al., 1992), Sdc2 knockout or mutant mice have not been reported. In Xenopus, endogenous Sdc2 protein is asymmetrically phosphorylated in ectoderm and is postulated to transmit either left- or right-sided information from ectoderm cells to migrating mesoderm during early gastrulation (Kramer et al., 2002; Kramer and Yost, 2002; Kramer and Yost, 2003). Sdc2 is also implicated in chick left-right (LR) patterning based on the observation that Sdc2 mRNA is asymmetrically expressed on the right side of Henson’s node (Fukumoto and Levin, 2005). In zebrafish, knockdown of embryonic Sdc2 perturbs angiogenesis and expression of the asymmetric markers lefty2 and pitx2 (Chen et al., 2004a). Although Sdc2 has been implicated in LR patterning in Xenopus, zebrafish and chick, the cellular mechanisms by which Sdc2 controls LR development are not known.

The establishment of vertebrate LR asymmetry is dependent on asymmetric fluid flow in a transient ciliated organ of asymmetry: the mouse nodal pit (Nonaka et al., 1998), the zebrafish Kupffer’s vesicle (KV) (Essner et al., 2005; Kramer-Zucker et al., 2005; Okabe et al., 2008) and the Xenopus gastrocoel roof plate (GRP) (Schweickert et al., 2007). Here, we show that: (1) Sdc2 functions in LR patterning by regulating KV morphogenesis; (2) Fgf2 is expressed exclusively in KV lineages at early stages of development and is required for KV morphogenesis; (3) KV-specific expression of Fgf2 is regulated by Tbx16, which in turn is dependent on Sdc2. In a series of synergy and epistasis experiments, we find that Sdc2 is at the head of a bifurcating pathway, controlling cilia length through Tbx16 and epithelial cell morphogenesis through both Tbx16 and Fgf2. Using cell lineage targeting in zebrafish KV, we show that Sdc2 has novel roles in LR development that are distinct from its roles in ectodermal lineages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish strains

Wild-type zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos were obtained from natural crosses of Oregon AB fish. Heterozygotes carrying the sptb104 allele were mated to generate spt-/- mutants (Griffin et al., 1998). Tg(sox17:GFP)s870 embryos were used to obtain time-lapse images of KV formation in live embryos (Sakaguchi et al., 2006) and to assess dorsal forerunner cell (DFC) proliferation. Embryos were maintained in embryo water between 24 and 28.5°C and staged according to age [hours post-fertilization (hpf)] and morphological criteria (Kimmel et al., 1995; Westerfield, 1994).

Injection of morpholinos (MOs) and synthesized mRNA

MOs designed against sdc2 were injected into zebrafish embryos at the 1- to 4-cell stage (global morphants), the 256- to 1000-cell stage (DFC morphants) or the dome stage (4.3 hpf; yolk morphants). For Sdc2, 8 ng/embryo splice-blocking MO SB1 (5′-GTGATGCAGACGCTCACCTGATCCC-3′) or SB2 (5′-CTCAGACTCTGACGGCTCACCTCTA-3′) or 6 ng/embryo translation-blocking MO (5′-ATCCAAAGGTTCCTCATAATTCCTC-3′) was injected. For Fgf2, 2 ng/embryo translation-blocking MO (5′-GGCCATCCCTAAGTCTGTCGGTCTC-3′) was injected. For Tbx16, 3 ng/embryo translation-blocking MO (5′-GCTTGAGGTCTCTGATAGCCTGCAT-3′) was injected. DFC and yolk morphants were co-injected with 1-2 ng/embryo Rhodamine-conjugated control MO (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′). Using a dissecting microscope with a Rhodamine filter cube, embryos with the appropriate MO accumulation in the DFCs or the yolk were selected for further analysis. Capped sense sdc2 mRNA was synthesized using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE in vitro transcription kit (Ambion) and purified as described previously (Rupp et al., 1994). For mRNA rescue experiments ∼100 pg/embryo sdc2 or fgf2 mRNA was injected into the embryo. All MO and mRNA injections were repeated at least three times.

In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes were synthesized by in vitro transcription using T3, T7 and SP6 polymerases. cDNA templates included cmlc2 (myl7 - Zebrafish Information Network) (Yelon et al., 1999), spaw (Long et al., 2003), sdc2 (Chen et al., 2004a), sox17 (Alexander and Stainier, 1999), charon (dand5 - Zebrafish Information Network) (Hashimoto et al., 2004), tbx16 (Griffin et al., 1998), ntl (Amack and Yost, 2004), shh (Essner et al., 2005), lft1 (Bisgrove et al., 1999), rfx2 (Neugebauer et al., 2009) and fgf2 (Lee et al., 2010). Whole-mount in situ hybridization was carried out as described previously (Thisse et al., 1993) using a Biolane HTI in situ machine (Huller and Huttner). Zebrafish embryos were cleared in 70% glycerol in PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20). Embryos were photographed using a Leica MZ12 stereo microscope and Dage-MTI DC330 CCD camera.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed overnight in a 1:1 mixture of 8% paraformaldehyde:1×PBS at 4°C and dehydrated stepwise into methanol for storage at -20°C. After stepwise rehydration, embryos were blocked for 1 hour in PBDT (1% BSA, 1% DMSO, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, pH 7.3) prior to treatment with primary or secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies included 1:100 rabbit polyclonal anti-ζPKC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-216), 1:200 mouse IgG anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma, T-6793) and 1:300 rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-histone H3 (Cell Signaling, 9701S). Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used at 1:200. Dissected embryos were equilibrated in Slowfade anti-fade buffer (Molecular Probes, 2828) and mounted on microscope slides for KV imaging. Embryos were imaged using an Olympus Fluoview laser-scanning confocal microscope with a 60× objective. To ensure consistent adjustment of microscope power and gain settings, wild-type embryos were imaged in all experiments.

Acridine Orange assay

Live embryos were immersed in 5 μg/ml Acridine Orange (Sigma) for 10 minutes then visualized and imaged for less than 60 seconds using a Leica M165 FC stereo microscope.

RESULTS

Knockdown of Sdc2 alters LR development in zebrafish

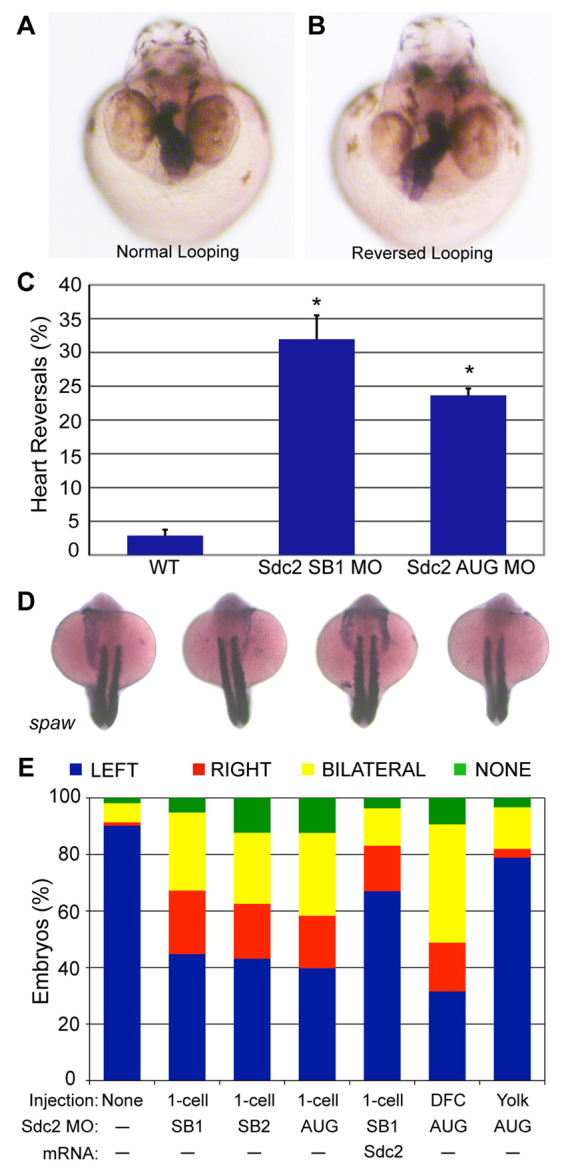

To explore the mechanism by which Sdc2 functions in zebrafish LR development, we performed a variety of targeted antisense morpholino (MO) knockdown experiments. Global gene knockdown in zebrafish is achieved when MOs are injected into the yolk prior to the 32-cell stage (2 hpf), knocking down gene function in all embryonic cells. Resulting embryos are referred to as ‘global morphants’. Although the overall appearance of global sdc2 morphants was relatively normal, both splice-blocking (SB) and translation-blocking (AUG) morphants had reversed heart and gut looping (SB1 MO: 32%, n=221; AUG MO: 24%, n=369; Fig. 1A-C). The Nodal family member southpaw (spaw) is normally expressed asymmetrically in the left lateral plate mesoderm (LPM). In global sdc2 morphants, with knockdown of Sdc2 by either AUG or SB MOs, the same LR phenotype was observed with three categories of aberrant spaw expression: right-side only (LR reversed), bilateral, or absent expression (Fig. 1D,E). As an important control for MO specificity, the left-sided expression of spaw was partially rescued from 42% to 64% with co-injection of MO-resistant sdc2 mRNA (Fig. 1E), suggesting that the LR phenotype is a specific effect of Sdc2 depletion. Additional evidence supporting sdc2 MO specificity has been published previously (Arrington and Yost, 2009).

Fig. 1.

Knockdown of Sdc2 in zebrafish KV causes laterality defects. (A,B) Heart looping is visualized by labeling the heart with an RNA in situ hybridization probe for cardiac myosin light chain 2 (cmlc2) at 40 hpf. (A) Normal heart looping. (B) Reversed heart looping. (C) Both SB and AUG sdc2 morphants had a statistically significant increase in reversed heart looping (SB1 MO: 32%, n=221; AUG MO: 24%, n=369) compared with wild-type (WT) embryos (3%, n=500), *P<0.001. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (D) Examples of morphant embryos at the 18-somite stage displaying left-sided, right-sided, bilateral and absent spaw expression. Somites are labeled with myod1 which is used as a marker for staging embryo development. (E) Expression of Nodal family member spaw is mostly left-sided in wild-type embryos (n=331) but in global sdc2 morphants spaw expression is randomized (SB1 MO, n=215; SB2 MO, n=229; AUG MO, n=190; all P<0.001). Aberrant spaw expression is partially rescued with co-injection of a MO-resistant sdc2 mRNA (n=123; P<0.001 compared with morphants). Targeting MO to the DFCs (DFCsdc2MO embryos, n=147) randomized spaw expression, but targeting MO exclusively to the yolk cell did not (yolksdc2MO embryos, n=181; P<0.001 compared with global and DFC morphants). These results indicate that the role of Sdc2 in LR development is cell-autonomous within the DFCs and that extra-embryonic Sdc2 is not involved in LR development. P-values by Student’s t-test.

The embryonic midline is important for maintaining a barrier between the left and right sides, and loss of midline integrity leads to a high incidence of altered organ orientation and bilateral gene expression in the LPM (Amack and Yost, 2004; Danos and Yost, 1996). To evaluate the integrity of the zebrafish notochord and floorplate, the midline markers lft1, ntl and shh were assessed by in situ hybridization analysis and found to have normal expression in global sdc2 morphants (supplementary material Fig. S1). These results indicate that a defective midline is not the cause of aberrant LR development in sdc2 morphants.

Since Sdc2 does not appear to be involved in midline development and sdc2 is widely expressed, including in and around KV and its precursors (supplementary material Fig. S2), we investigated whether Sdc2 in KV cell lineages is required for normal LR development. In zebrafish, a group of ∼24 mesenchymal cells, called dorsal forerunner cells (DFCs), migrate at the leading edge of the embryonic shield during gastrulation (Cooper and D’Amico, 1996; Melby et al., 1996). In contrast to other cells in this region, DFCs do not involute until the end of gastrulation, at which time they transition from mesenchymal to epithelial cells to form the ciliated lining of KV. Utilizing a method, termed DFCMO, that was previously developed to knockdown genes in this lineage to assess their cell-autonomous roles in KV formation, ciliogenesis and LR patterning (Amack and Yost, 2004; Essner et al., 2005), we knocked down Sdc2 in DFCs, KV and yolk cells, but not in the rest of the embryo. Strikingly, DFCsdc2MO morphants had the same pattern of altered spaw expression as seen in global morphants (Fig. 1E). As an important control, embryos with sdc2 MO targeted exclusively to yolk (yolkMO) by injection at the dome stage, after cytoplasmic bridges between the yolk and DFCs have closed, had less aberrant spaw expression, with a statistically significant increase in normal, left-sided expression (Fig. 1E). Together, these results indicate that Sdc2 is required in DFC/KV lineages for normal LR development.

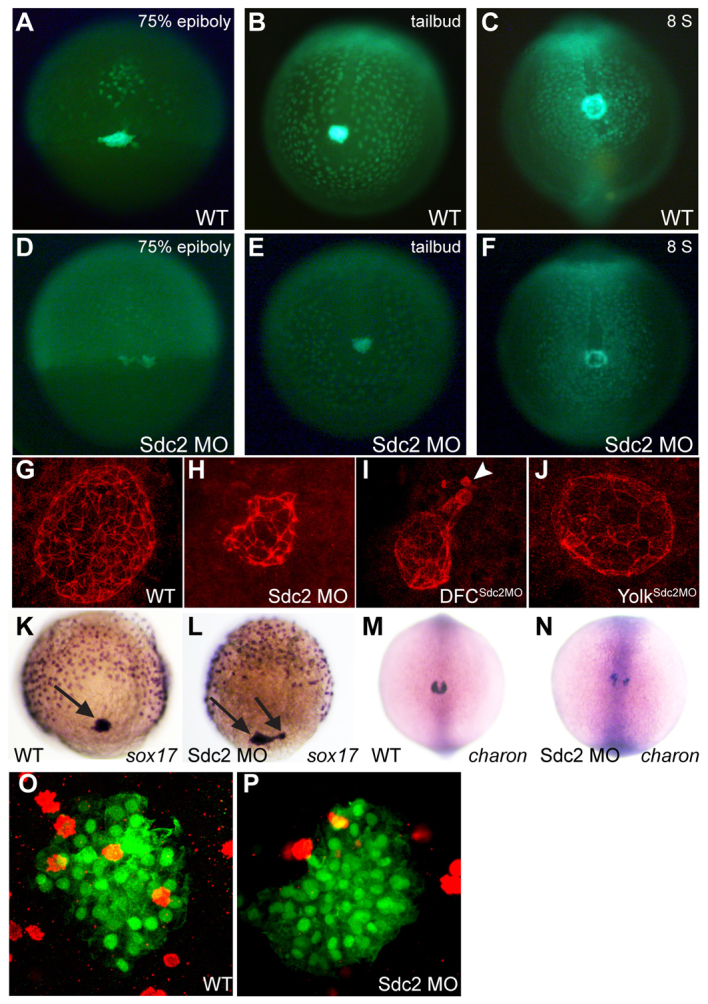

Sdc2 cell-autonomously regulates KV morphogenesis

Global knockdown of Sdc2 has striking effects on KV morphogenesis, as visualized by time-lapse imaging of live transgenic Sox17-GFP embryos (Fig. 2A-F) and immunohistochemical analysis of the KV (Fig. 2G-J) using the epithelial marker atypical PKC (anti-ζPKC). In wild-type embryos, the KV is spherical with smooth borders (Fig. 2C,G), whereas the DFCs in sdc2 global morphants fail to coalesce normally, resulting in misshapen KVs (Fig. 2F,H). We previously found that yolk sdc2 non-cell-autonomously regulates cardiac and gut primordia migration, but sdc2 expressed in cardiac and gut primordia was not required for their migration (Arrington and Yost, 2009). To determine the cell lineage required for KV morphogenesis, we used DFCMO targeting. DFCsdc2MO embryos had KV defects that were more severe than seen in global sdc2 morphants. KVs in DFC-targeted morphants were severely misshapen, nonspherical and smaller, with some detached cells (Fig. 2I, arrowhead). By contrast, yolksdc2MO embryos had normal KV morphogenesis (Fig. 2J), which correlates with normal LR patterning (Fig. 1E). Thus, although yolk Sdc2 is non-cell-autonomously required for cardiac and gut primordia migration (Arrington and Yost, 2009), yolk Sdc2 is not necessary for KV morphogenesis.

Fig. 2.

Cell-autonomous regulation of KV morphogenesis by Sdc2. (A-F) Comparison of time-lapse images of uninjected (A-C) and sdc2 morphant (D-F) Tg(sox17:GFP) zebrafish embryos illustrates defective DFC coalescence and KV morphogenesis in sdc2 morphants. KV morphology and size were affected by variation in DFC number and coalescence. (G-J) Anti-ζPKC antibody labels the apical surface of KV cells lining the KV lumen. At the 8-somite stage (SS), KV morphology was normal in wild-type (G) and yolksdc2MO (J) embryos. By contrast, global sdc2 morphants (H) and DFCsdc2MO embryos (I) displayed abnormalities in KV shape as well as incomplete DFC incorporation into the main KV, resulting in aberrant secondary ‘mini vesicles’ (arrowhead in I). (K,L) sox17 expression at 80-90% epiboly reveals tightly clustered DFCs (arrows) in wild-type embryos (K) but loosely adherent DFCs in sdc2 morphants (L). (M,N) Expression of charon is perturbed in sdc2 morphants, indicating KV disorganization. (O,P) pH3 staining in DFCs of wild type [Tg(sox17:GFP)s870] and sdc2 morphants at tailbud to 2-somite stage (see also Table 1).

To better understand the mechanism by which Sdc2 functions in KV formation, we evaluated the expression of gfp in live transgenic sox17-GFP embryos, as well as that of a DFC specification marker, sox17, in fixed embryos. We found that gfp (in transgenic embryos) and sox17 (in fixed embryos) were expressed within DFCs of sdc2 morphants (Fig. 2D,L), indicating that DFC specification was normal. DFCs also appeared to be positioned normally at the leading margin of epibolic movement, indicating that loss of Sdc2 does not alter the global migration of DFCs. Despite appropriate localization at the margin during epiboly, DFC coalescence and adhesion were abnormal. In wild-type embryos, DFCs were tightly packed together in most embryos (70%, n=17; Fig. 2A,K), whereas DFCs were dispersed and loosely adherent in sdc2 morphants (35% tightly packed, n=28; Fig. 2D,L), with a higher incidence of separate DFC clusters in morphants. Analysis of gfp expression in the DFCs of morphant sox17-GFP embryos at the tailbud stage (compare Fig. 2B with 2E), as well as of the peri-KV marker charon, confirmed DFC disorganization during KV formation. charon is normally expressed in a horseshoe pattern around KV in wild-type embryos (Fig. 2M; 94% normal, n=86) but was disorganized in sdc2 morphants (Fig. 2N; 45% normal, n=109). Overall, DFC specification occurs in sdc2 morphants and DFCs migrate to the appropriate location within the tailbud where KV formation takes place. However, cell coalescence is impaired in DFCs, leading to a misshapen KV (Fig. 2H,I), with some DFCs failing to incorporate fully into the KV (Fig. 2I).

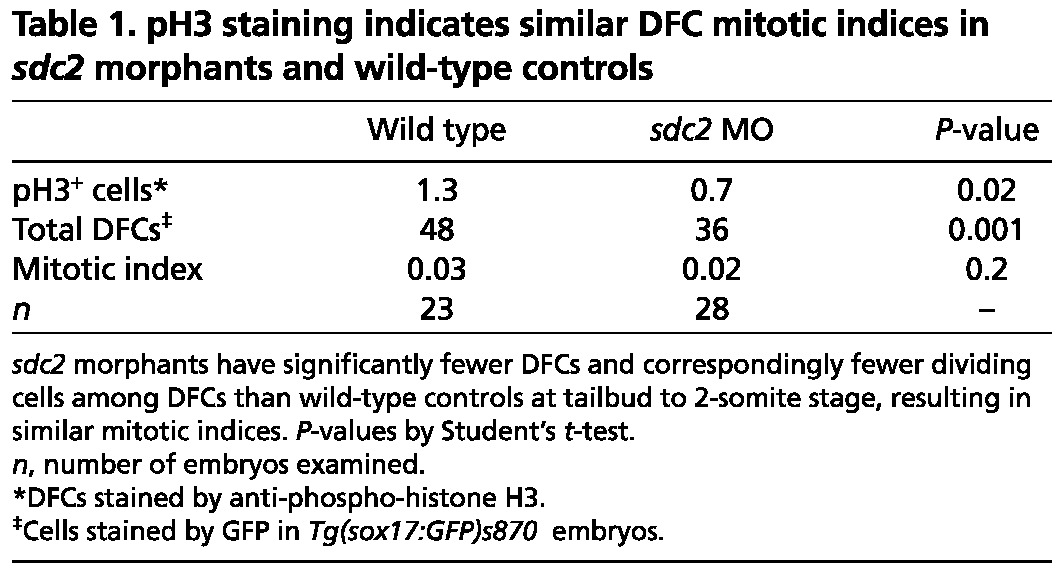

In addition to the defective DFC coalescence seen in sdc2 morphants, many morphants appeared to have fewer DFCs (compare Fig. 2A with 2D), and the decreased cell number persisted through KV formation (compare Fig. 2C with 2F). To determine whether this was due to defective cell proliferation we evaluated the DFCs between the tailbud and 2-somite stages using anti-phospho-histone H3 (pH3) in Tg(sox17:GFP)s870 embryos. There were significantly fewer pH3-positive DFCs in sdc2 morphants than in wild-type controls. However, because sdc2 morphants had fewer total DFCs at these stages, the mitotic indices were the same (Fig. 2O,P, Table 1). To assess cell apoptosis we stained wild type and sdc2 morphants with Acridine Orange, and found no difference in apoptotic rates (supplementary material Fig. S2). Thus, reduced cell proliferation during epiboly and failure of DFCs to incorporate into the forming KV explain the small KV phenotype seen in sdc2 morphants (see Fig. 2D-F,H,I). Taken together, these results indicate that Sdc2 cell-autonomously regulates DFC proliferation and coalescence during KV formation.

Table 1.

pH3 staining indicates similar DFC mitotic indices in sdc2 morphants and wild-type controls

Sdc2 is required for KV ciliogenesis and fluid flow

Quantitative analysis of KV cilia in global sdc2 morphants and in DFCsdc2MO morphants revealed that they are shorter (Fig. 3A-E) than in wild-type and yolksdc2MO embryos. Thus, it appears that zebrafish Sdc2 also plays a cell-autonomous role in KV cilia formation. In addition to shortened cilia, sdc2 morphants also had fewer cilia (Fig. 3F), providing further evidence for defective DFC proliferation and/or incorporation into the forming KV.

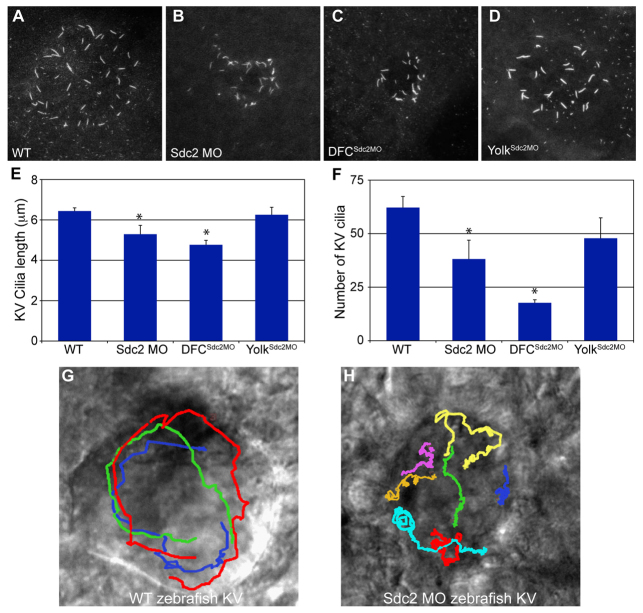

Fig. 3.

Cell-autonomous regulation of KV ciliogenesis and asymmetric fluid flow by Sdc2. (A-D) KV cilia labeled with anti-tubulin antibody were shorter in global sdc2 (B) and DFCsdc2MO (C) morphant zebrafish embryos than in wild-type (A) and yolksdc2MO (D) embryos. (E,F) Cilia length and number were reduced in global and DFCsdc2MO morphants (global morphants: seven embryos, 267 cilia; DFCsdc2MO: ten embryos, 177 cilia) compared with wild-type and yolksdc2MO embryos (wild type: six embryos, 373 cilia; yolksdc2MO: six embryos, 287 cilia), *P<0.05 (Student’s t-test). Error bars indicate s.e.m. (G,H) KV fluid flow was altered in sdc2 morphants. Bead tracks are circular in wild-type embryos (G) but disorganized in sdc2 morphants (H).

To evaluate whether the shorter cilia in sdc2 morphants are capable of generating normal fluid flow in dysmorphic KV, fluorescent beads were injected into KV and imaged using time-lapse photography. Wild-type embryos displayed motile cilia that give rise to the stereotypical counterclockwise flow within KV (Fig. 3G). Cilia in sdc2 morphants were motile, as indicated by localized bead movement, but flow was disorganized, meandering, and not persistently counterclockwise (Fig. 3H). These results indicate that Sdc2 plays a cell-autonomous role in KV morphogenesis and ciliogenesis and that the combination of defects is likely to be the proximate cause of aberrant downstream LR development in zebrafish sdc2 morphants.

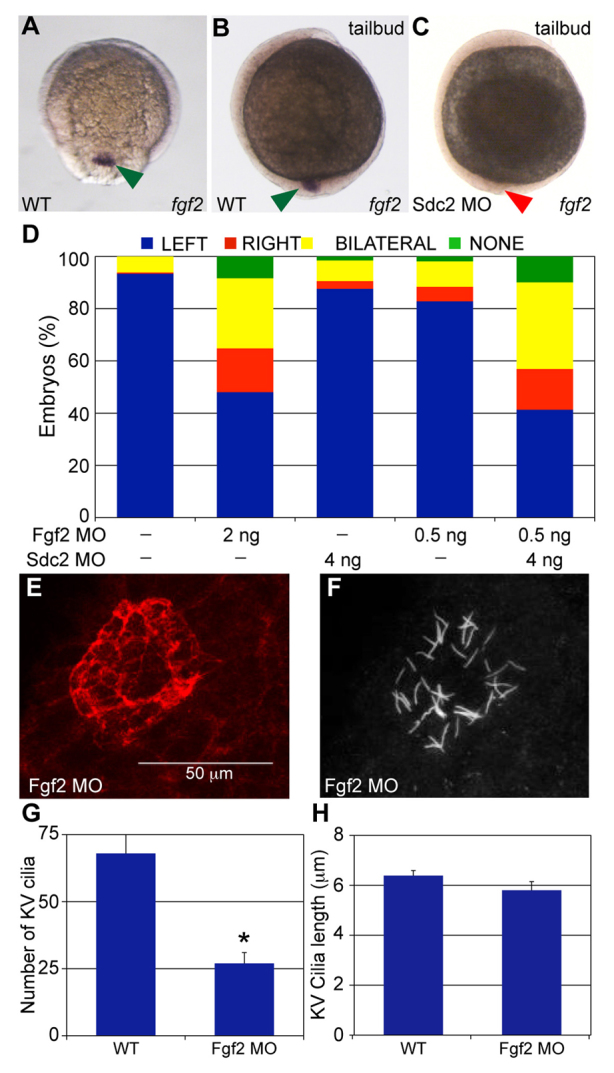

Fgf2 and Sdc2 function in the same pathway for KV morphogenesis

During our search for genes that function downstream of Sdc2 in KV formation, we discovered that fgf2 expression is restricted to migrating DFCs and KV cells during early embryogenesis (Fig. 4A,B). To date, Fgf2 is the only known cell signaling ligand that is expressed exclusively in ciliated cells and their precursors. Given the evidence from cell culture experiments that members of the syndecan family interact with members of the FGF signaling family, we explored the functions and regulation of Fgf2 in relation to Sdc2 in LR patterning. We found that fgf2 expression in KV is dependent on Sdc2, with fgf2 expression significantly reduced or absent in 60% of sdc2 morphants (n=106; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Sdc2 controls KV morphogenesis through Fgf2 in DFCs/KV. (A,B) In wild-type zebrafish embryos, fgf2 (arrowheads) is expressed (A) in DFCs at 80% epiboly (dorsal view) and (B) in the forming KV at tailbud stage (lateral view). (C) In sdc2 morphants, fgf2 expression is significantly reduced in KV cells (lateral view). (D) fgf2 morphants (2 ng MO) had randomized spaw expression (n=244), similar to that seen in sdc2 morphants (see Fig. 1E). Synergy between Sdc2 and Fgf2 was tested by comparing the effects of subthreshold amounts of each MO individually [4 ng sdc2 SB2 MO (n=431) and 0.5 ng fgf2 MO (n=475)] with co-injection of both MOs. Spaw expression patterns were significantly altered by co-injection of subthreshold doses of sdc2 SB2 and fgf2 MOs [n=486; P<0.001 compared with individual low-dose morphants]. (E,F) fgf2 morphants had smaller KVs (E; labeled with anti-ζPKC antibody) than wild-type embryos, whereas cilia (F, labeled with anti-tubulin antibody) were of normal length. (G,H) Quantification of cilia number and length: cilia number but not cilia length was decreased in fgf2 morphants (wild type: eight embryos, 547 cilia; fgf2 morphants: 11 embryos, 299 cilia), *P<0.001. Error bars indicate s.e.m. P-values by Student’s t-test.

To test whether Fgf2 has roles in LR patterning, we injected fgf2 MO (Lee et al., 2010) into 1- to 2-cell embryos and found that spaw expression in LPM is abnormal, with a high incidence of bilateral expression and, to a lesser extent, right-side only or absent expression (Fig. 4D), a phenotype similar to that of sdc2 morphants. Taken together, these findings suggest that Fgf2 functions downstream of Sdc2 in LR development. To further test whether Sdc2 and Fgf2 function in the same pathway for LR development, we performed synergy experiments using subthreshold doses of MO. Injection of 4 ng sdc2 MO alone or 0.5 ng fgf2 MO alone had minimal effects on LR patterning, as assayed by spaw expression patterns in LPM (Fig. 4D). By contrast, when these subthreshold MO doses were co-injected, spaw expression patterns were significantly altered (Fig. 4D), comparable to the effect of single higher doses of either MO. KV in fgf2 morphants was also dysmorphic and smaller than in wild type, with fewer cilia (Fig. 4E-G), phenotypes similar to those observed in sdc2 morphants. However, in contrast to sdc2 morphants, the average cilia length in fgf2 morphants was normal (Fig. 4H). Together, these results suggest that Sdc2 and Fgf2 function together to regulate KV morphogenesis and downstream LR patterning, but that the regulation of ciliogenesis by Sdc2 does not depend on Fgf2.

Sdc2 regulates KV morphogenesis through Tbx16 and Fgf2

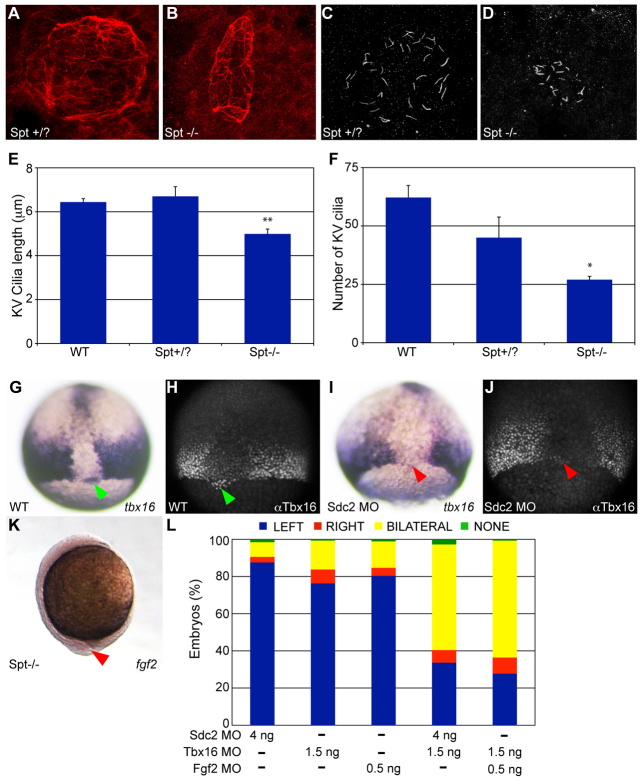

The dysmorphic KV/short cilia phenotype seen in sdc2 morphants (Fig. 2H,I and Fig. 3B,C) was similar to that seen in spadetail (spt; tbx16) mutants/morphants (Fig. 5A-F) (Amack et al., 2007). Analysis of both tbx16 mRNA and Tbx16 protein in sdc2 morphants revealed normal expression throughout the embryo except in the DFCs, where tbx16 expression was significantly reduced or absent (wild-type embryos: 100% with strong tbx16 expression in DFCs, n=24; sdc2 morphants: 68% with reduced/absent tbx16 expression in DFCs, n=22; Fig. 5G-J). These data suggest that Sdc2 is required in DFC/KV lineages, but not in other lineages, for tbx16 expression.

Fig. 5.

Sdc2 controls DFC/KV-specific expression of Tbx16, upstream of both Fgf2-dependent KV morphogenesis and Fgf2-independent cilia length regulation. (A-F) KV morphogenesis and cilia length defects in spadetail (spt; tbx16) mutants. (A,C) Normal KV morphology (A) and cilia length (C) in wild type or spt heterozygotes. (B,D) spt mutants had defective KV morphogenesis (B) and cilia length (D), similar to sdc2 morphants. (E,F) Quantification of (E) cilia length and (F) cilia number (spt+/?: eight embryos, 361 cilia; spt-/-: nine embryos, 242 cilia) indicated that both are decreased in spt mutants (*P<0.05, **P<0.001). Error bars indicate s.e.m. (G-L) Sdc2 regulates Tbx16 expression in DFCs/KV. (G,H) Green arrowheads indicate (G) tbx16 RNA and (H) Tbx16 protein expression in DFCs in wild-type embryos. (I,J) Red arrowheads indicate the position of DFCs lacking (I) tbx16 mRNA and (J) Tbx16 protein expression in sdc2 morphants. By contrast, tbx16 RNA and Tbx16 protein expression in adjacent non-DFC domains was normal, revealing a domain-specific regulation of Tbx16 by Sdc2. (K) fgf2 was downregulated in spt mutants (compare with wild type in Fig. 4B). (L) Synergy between Sdc2, Tbx16 and Fgf2 was tested by injection of subeffective amounts of each MO individually (sdc2 SB2 MO, n=431; tbx16 MO, n=396; fgf2 MO, n=475) compared with co-injections of pairs of subthreshold MOs. Co-injection of sdc2 SB2 and tbx16 MOs (n=251) and co-injection of tbx16 and fgf2 MOs (n=111) resulted in significantly affected spaw expression (P<0.001) compared with single injections of subthreshold MOs. P-values by Student’s t-test.

These observations place Sdc2 upstream of Tbx16 expression in DFC/KV lineages, and raise the possibility that the dysmorphic KV phenotype observed in tbx16 mutants/morphants is mediated by Fgf2. To explore this possibility, fgf2 expression was evaluated in spt mutants and morphants and found to be significantly reduced or absent (0% normal, n=43 mutants and n=39 morphants; Fig. 5K), indicating that fgf2 is downstream of Tbx16. Although we attempted to rescue the KV phenotype in sdc2 morphants by co-injecting tbx16 mRNA, this was unsuccessful because overexpression of tbx16 has a disruptive effect on tailbud formation (data not shown). Therefore, we performed synergy experiments to further explore the possibility that Tbx16 is in the same pathway as Sdc2 and Fgf2. In these experiments, subthreshold doses of tbx16 MO were combined with low-dose sdc2 or fgf2 MO. In each case, a combination of low-dose MOs resulted in significantly altered spaw expression, whereas any single low-dose MO alone had a minimal effect on LR patterning (Fig. 5L). To better define the epistatic relationship among these genes, expression of sdc2 was evaluated in tbx16 and fgf2 morphants. As in wild-type embryos, sdc2 was globally expressed in tbx16 and fgf2 morphant embryos (supplementary material Fig. S2A-C). In fgf2 morphants, tbx16 expression was strong, including within DFCs (supplementary material Fig. S2D,E). These results indicate that Fgf2 is not required for sdc2 or tbx16 expression, further supporting its position as a downstream effector of sdc2 and tbx16.

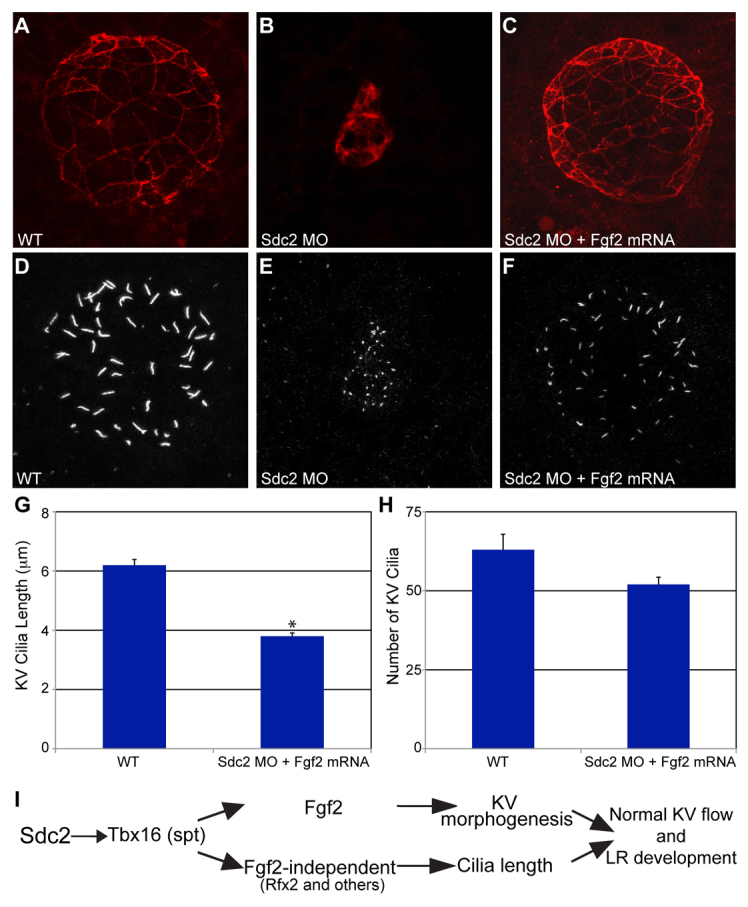

The role of fgf2 in KV formation was further investigated by rescue experiments in which fgf2 mRNA was co-injected into sdc2 morphants. With co-injection of fgf2 mRNA we observed significant rescue of KV morphology (normal KV morphology: 47% for fgf2 mRNA-rescued sdc2 morphants versus 10% for sdc2 morphants, n=30 for each; Fig. 6A-F). Among KV with rescued morphology, cilia number was rescued but not cilia length (Fig. 6G,H). Presumably because of the residual cilia length defect, LR development as manifest by spaw expression was not rescued (only 41% had normal left-sided expression, n=143). These experiments confirm a role for Fgf2 in DFC coalescence and cell proliferation during KV morphogenesis and indicate that ciliogenesis is controlled through an Fgf2-independent pathway. In addition, they illustrate that normal LR patterning is dependent upon both normal KV morphology and cilia length.

Fig. 6.

fgf2 mRNA rescues KV morphogenesis and cilia number, but not cilia length, in sdc2 morphants. (A-C) Co-injection of sdc2 AUG MO and fgf2 mRNA rescued KV morphology (labeled with anti-ζPKC antibody). (D-H) Among rescued KV, cilia number in sdc2 morphants was partially rescued by fgf2 mRNA co-injection, but cilia length was not rescued (wild type: seven embryos, 444 cilia; sdc2 morphants + fgf2 mRNA: eight embryos, 416 cilia; compare with sdc2 morphants alone, Fig. 3E,F). *P<0.001 (Student’s t-test). Error bars indicate s.e.m. (I) Proposed genetic pathway by which Sdc2 controls KV morphogenesis and ciliogenesis. DFC-expressed Sdc2 is required for tbx16 expression, which in turn regulates fgf2-dependent KV morphogenesis and fgf2-independent ciliogenesis.

In summary, our results indicate that Sdc2 functions upstream of Tbx16 in the DFC/KV cell lineage, that KV morphogenesis is controlled through an Fgf2-dependent pathway, and that ciliogenesis is controlled through an Fgf2-independent pathway (Fig. 6I).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the HSPG core protein Sdc2 is shown to function cell-autonomously in the vertebrate ciliated organ of asymmetry, as represented by KV in zebrafish. We found that Sdc2 is a novel regulator of Tbx16 in KV and functions in epithelial morphogenesis and in the generation of cilia of normal length. Furthermore, we show that Fgf2 is expressed exclusively in DFCs/KV cells. Strikingly, knockdown of Fgf2 results in defective KV morphogenesis but normal cilia length, suggesting for the first time that cilia length regulation can be independent of KV epithelial morphogenesis. The loss of Tbx16 and Fgf2 in sdc2 morphants is most likely caused by loss of Sdc2-mediated intracellular signaling rather than other cellular mechanisms, as several other aspects of cell behavior are unaffected by Sdc2 knockdown, including the ability to activate a battery of other DFC markers, the ability to migrate to the appropriate position within the tailbud, the ability to form a KV lumen (although dysmorphic) and to initiate cilia formation (although shorter). Hence, we propose that loss of Sdc2 directly alters at least two molecular pathways within KV (Fig. 6I): Fgf2-dependent KV morphogenesis and Fgf2-independent cilia length regulation.

Sdc2 regulates LR development through multiple lineage-specific functions

Although sdc2 is expressed ubiquitously during early zebrafish development, we find that it functions in a lineage-specific manner. We previously reported that extra-embryonic sdc2, expressed in yolk, is required for embryonic fibrillogenesis and non-cell-autonomous regulation of heart and gut primordia migration (Arrington and Yost, 2009), whereas embryonic sdc2 is not required for these processes. Knockdown of Sdc2 in yolk cell lineages causes cardia bifida and a bifid gut, but normal LR patterning (Arrington and Yost, 2009) (Fig. 1E). By contrast, targeted knockdown of Sdc2 in DFCs/KV cells reveals that Sdc2 has cell-autonomous functions within the DFCs to regulate tbx16 and the bifurcating fgf2-dependent and fgf2-independent pathways to control KV morphogenesis and KV ciliogenesis, respectively.

Sdc2 is the first known upstream regulator of tbx16 in zebrafish. Strikingly, with global knockdown of Sdc2 the expression of tbx16 is altered in DFCs/KV but not in adjacent tissues that also express tbx16 (Fig. 5). This suggests that Sdc2 might be the primary HSPG functioning in DFCs/KV, and that other HSPG core proteins provide redundant regulation of tbx16 in other tissues. Alternatively, cell-specific HS-GAG modifications, through families of sulfotransferases with tissue- and development-specific expression patterns (Cadwallader and Yost, 2006a; Cadwallader and Yost, 2006b; Cadwallader and Yost, 2007), might enable Sdc2 to regulate tbx16 expression in DFCs/KV, but not in other tissues.

Regulation of multiple pathways by Sdc2

Given the complexities of the GAG chains attached to Sdc2 and other proteoglycans, it is not surprising that knockdown of a core protein would attenuate bifurcating cell signaling pathways within the same lineage, and that the same Sdc2 core protein might regulate different cell signaling pathways in other cell lineages. For example, Sdc2 in Xenopus ventral animal cap lineages appears to control LR patterning through the non-cell-autonomous regulation of components of the TGFβ superfamily (Kramer et al., 2002). By contrast, we show that Sdc2 cell-autonomously regulates KV morphogenesis in zebrafish. Thus, different cell lineages utilize Sdc2 through distinct cell signaling pathways that can converge on LR patterning.

Although this is the first report of Fgf2 being involved in LR development and KV morphogenesis, other FGF family members have been implicated in KV function. Zebrafish mutants and morphants of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (fgfr1) and fgf8/fgf24 were found to have shortened KV cilia, while there are conflicting reports as to whether fgf8 morphants have defective KV morphogenesis (Matsui et al., 2011; Neugebauer et al., 2009). Overall, it appears that distinct FGF pathways function within DFCs/KV cells and are required for normal LR patterning, allowing the experimental separation of KV ciliogenesis from KV morphogenesis. Here we show that Fgf2 is important for KV morphogenesis but not KV cilia length, and that both of these processes, ciliogenesis and KV morphogenesis, are dependent on Sdc2 and Tbx16 (Fig. 6I). By contrast, Fgf24 and Fgfr1 are important for ciliogenesis but not KV morphogenesis.

Summary

Our findings provide insight into multiple functions of the HSPG core protein Sdc2 and emphasize the importance of lineage specificity for HSPG function. In yolk cells, Sdc2 non-cell-autonomously controls extracellular matrix fibrillogenesis and cardiac and gut primordia migration. In DFCs/KV cells, Sdc2 cell-autonomously controls Tbx16 expression, as well as two bifurcating downstream pathways that regulate Fgf2-dependent KV morphogenesis and Fgf2-independent KV ciliogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and Primary Children’s Medical Foundation to H.J.Y. C.B.A. was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health [K08HD062638]. A.G.P. was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health T-32 Cardiology Training Grant. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

H.J.Y. directed the project. C.B.A. and A.G.P. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. C.B.A., A.G.P. and H.J.Y. interpreted data and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.096933/-/DC1

References

- Alexander J., Stainier D. Y. (1999). A molecular pathway leading to endoderm formation in zebrafish. Curr. Biol. 9, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amack J. D., Yost H. J. (2004). The T box transcription factor no tail in ciliated cells controls zebrafish left-right asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 14, 685–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amack J. D., Wang X., Yost H. J. (2007). Two T-box genes play independent and cooperative roles to regulate morphogenesis of ciliated Kupffer’s vesicle in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 310, 196–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrington C. B., Yost H. J. (2009). Extra-embryonic syndecan 2 regulates organ primordia migration and fibrillogenesis throughout the zebrafish embryo. Development 136, 3143–3152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield M., Kokenyesi R., Kato M., Hinkes M. T., Spring J., Gallo R. L., Lose E. J. (1992). Biology of the syndecans: a family of transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8, 365–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove B. W., Essner J. J., Yost H. J. (1999). Regulation of midline development by antagonism of lefty and nodal signaling. Development 126, 3253–3262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwallader A. B., Yost H. J. (2006a). Combinatorial expression patterns of heparan sulfate sulfotransferases in zebrafish: I. The 3-O-sulfotransferase family. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3423–3431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwallader A. B., Yost H. J. (2006b). Combinatorial expression patterns of heparan sulfate sulfotransferases in zebrafish: II. The 6-O-sulfotransferase family. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3432–3437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwallader A. B., Yost H. J. (2007). Combinatorial expression patterns of heparan sulfate sulfotransferases in zebrafish: III. 2-O-sulfotransferase and C5-epimerases. Dev. Dyn. 236, 581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey D. J. (1997). Syndecans: multifunctional cell-surface co-receptors. Biochem. J. 327, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E., Hermanson S., Ekker S. C. (2004a). Syndecan-2 is essential for angiogenic sprouting during zebrafish development. Blood 103, 1710–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Klass C., Woods A. (2004b). Syndecan-2 regulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15715–15718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. S., D’Amico L. A. (1996). A cluster of noninvoluting endocytic cells at the margin of the zebrafish blastoderm marks the site of embryonic shield formation. Dev. Biol. 180, 184–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman J. R. (2003). Syndecans: proteoglycan regulators of cell-surface microdomains? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 926–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danos M. C., Yost H. J. (1996). Role of notochord in specification of cardiac left-right orientation in zebrafish and Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 177, 96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essner J. J., Amack J. D., Nyholm M. K., Harris E. B., Yost H. J. (2005). Kupffer’s vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development 132, 1247–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears C. Y., Gladson C. L., Woods A. (2006). Syndecan-2 is expressed in the microvasculature of gliomas and regulates angiogenic processes in microvascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14533–14536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto T., Levin M. (2005). Asymmetric expression of Syndecan-2 in early chick embryogenesis. Gene Expr. Patterns 5, 525–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin K. J., Amacher S. L., Kimmel C. B., Kimelman D. (1998). Molecular identification of spadetail: regulation of zebrafish trunk and tail mesoderm formation by T-box genes. Development 125, 3379–3388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H., Rebagliati M., Ahmad N., Muraoka O., Kurokawa T., Hibi M., Suzuki T. (2004). The Cerberus/Dan-family protein Charon is a negative regulator of Nodal signaling during left-right patterning in zebrafish. Development 131, 1741–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer K. L., Yost H. J. (2002). Ectodermal syndecan-2 mediates left-right axis formation in migrating mesoderm as a cell-nonautonomous Vg1 cofactor. Dev. Cell 2, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer K. L., Yost H. J. (2003). Heparan sulfate core proteins in cell-cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37, 461–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer K. L., Barnette J. E., Yost H. J. (2002). PKCgamma regulates syndecan-2 inside-out signaling during Xenopus left-right development. Cell 111, 981–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer-Zucker A. G., Olale F., Haycraft C. J., Yoder B. K., Schier A. F., Drummond I. A. (2005). Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer’s vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development 132, 1907–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Park H., Chung H., Choi S., Kim Y., Yoo H., Kim T. Y., Hann H. J., Seong I., Kim J., et al. (2009). Syndecan-2 regulates the migratory potential of melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27167–27175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. O., Choe H., Seo K., Lee H., Lee J., Kim J. (2010). Fgfbp1 is essential for the cellular survival during zebrafish embryogenesis. Mol. Cells 29, 501–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S., Ahmad N., Rebagliati M. (2003). The zebrafish nodal-related gene southpaw is required for visceral and diencephalic left-right asymmetry. Development 130, 2303–2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Thitamadee S., Murata T., Kakinuma H., Nabetani T., Hirabayashi Y., Hirate Y., Okamoto H., Bessho Y. (2011). Canopy1, a positive feedback regulator of FGF signaling, controls progenitor cell clustering during Kupffer’s vesicle organogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9881–9886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby A. E., Warga R. M., Kimmel C. B. (1996). Specification of cell fates at the dorsal margin of the zebrafish gastrula. Development 122, 2225–2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhaupt H. A., Yoneda A., Whiteford J. R., Oh E. S., Lee W., Couchman J. R. (2009). Syndecan signaling: when, where and why? J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 60 Suppl. 4, 31–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer J. M., Amack J. D., Peterson A. G., Bisgrove B. W., Yost H. J. (2009). FGF signalling during embryo development regulates cilia length in diverse epithelia. Nature 458, 651–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguer O., Villena J., Lorita J., Vilaro S., Reina M. (2009). Syndecan-2 downregulation impairs angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 795–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka S., Tanaka Y., Okada Y., Takeda S., Harada A., Kanai Y., Kido M., Hirokawa N. (1998). Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell 95, 829–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe N., Xu B., Burdine R. D. (2008). Fluid dynamics in zebrafish Kupffer’s vesicle. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3602–3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp R. A., Snider L., Weintraub H. (1994). Xenopus embryos regulate the nuclear localization of XMyoD. Genes Dev. 8, 1311–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi T., Kikuchi Y., Kuroiwa A., Takeda H., Stainier D. Y. (2006). The yolk syncytial layer regulates myocardial migration by influencing extracellular matrix assembly in zebrafish. Development 133, 4063–4072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert A., Weber T., Beyer T., Vick P., Bogusch S., Feistel K., Blum M. (2007). Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 17, 60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C., Thisse B., Schilling T. F., Postlethwait J. H. (1993). Structure of the zebrafish snail1 gene and its expression in wild-type, spadetail and no tail mutant embryos. Development 119, 1203–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villena J., Berndt C., Granes F., Reina M., Vilaro S. (2003). Syndecan-2 expression enhances adhesion and proliferation of stably transfected Swiss 3T3 cells. Cell Biol. Int. 27, 1005–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (1994). The Zebrafish Book. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press; [Google Scholar]

- Yelon D., Horne S. A., Stainier D. Y. (1999). Restricted expression of cardiac myosin genes reveals regulated aspects of heart tube assembly in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 214, 23–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.