Abstract

Transcription is regulated by sequence-specific transcription factors (TFs) that bind to short genomic DNA elements that can be located in promoters, enhancers and other cis-regulatory modules. Determining which TFs bind where requires techniques that enable the ab initio identification of TF-DNA interactions. These techniques can either be “TF-centered” (protein-to-DNA), where regions of DNA to which a TF of interest binds are identified, or “gene-centered” (DNA-to-protein), where TFs that bind a DNA sequence of interest are identified. Here we describe gene-centered yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays. Briefly, in Y1H assays, a DNA fragment is cloned upstream of two different reporters, and these reporter constructs are integrated into the genome of a yeast strain. Next, plasmids expressing TFs as hybrid proteins (hence the name of the assay) fused with the strong transcriptional activation domain (AD) of the yeast TF Gal4 are introduced into the yeast strain. When a TF interacts with the DNA fragment of interest, the AD moiety activates reporter expression in yeast regardless of whether the TF is an activator or repressor in vivo. Sequencing the plasmid in each of these colonies reveals the identity of the TFs that can bind the DNA fragment. We have shown Y1H to be a robust method for detecting interactions between a variety of DNA elements and multiple families of TFs.

Keywords: Transcription factor, yeast one-hybrid, gene expression, transcription

1. Introduction

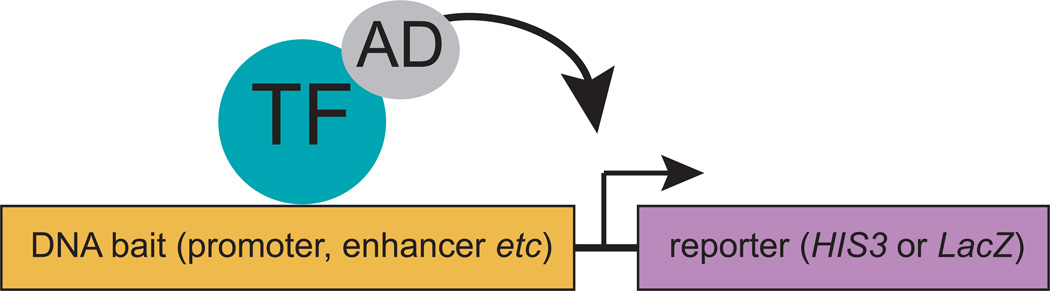

The yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay is a genetic method for identifying proteins that can interact with a DNA sequence of interest (1, 2) (Fig. 1). The assay is similar to the widely-used yeast two-hybrid assay that identifies protein-protein interactions, either in small or large-scale settings (3–5). An outline of the Y1H protocol is provided in Figure 2. Briefly, a DNA fragment is cloned upstream of two different reporters, and these reporter constructs are integrated into the genome of a yeast strain. Next, plasmids expressing TFs as hybrid proteins (hence the name of the assay) fused with the strong transcriptional activation domain (AD) of the yeast Gal4 transcription factor are introduced into the yeast strain. When a TF interacts with the DNA fragment of interest, the AD moiety activates reporter expression in yeast regardless of whether the TF is an activator or repressor in vivo. Sequencing the plasmid in each of these colonies reveals the identity of the TFs that can bind the DNA fragment.

Fig. 1.

Cartoon of Y1H assay: TF – transcription factor; AD – Gal4 transcription activation domain.

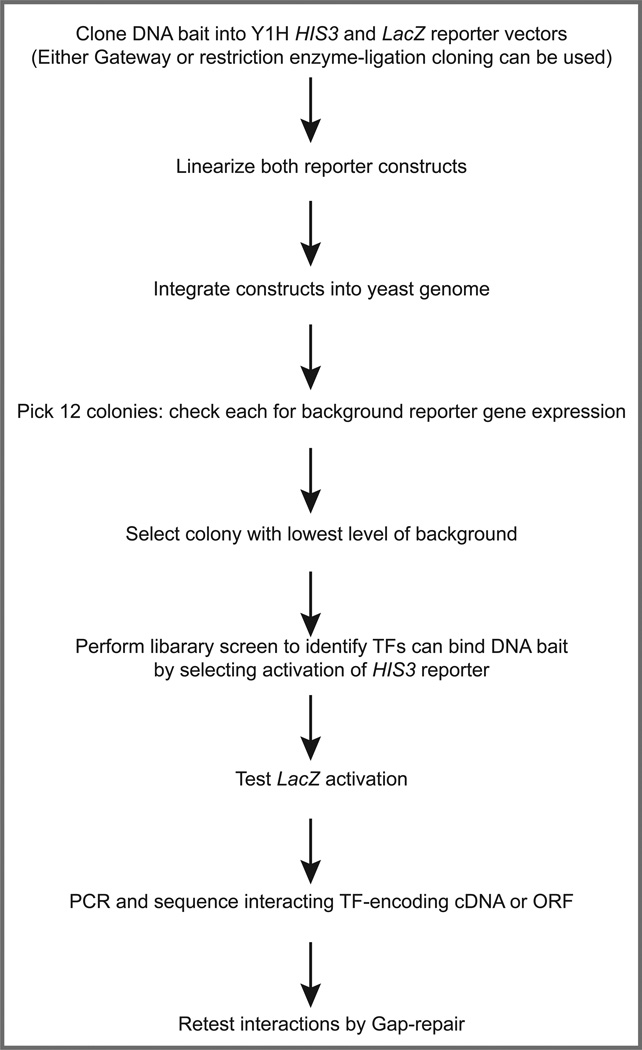

Fig. 2.

Outline of Y1H cDNA library screen procedure.

The Y1H assay provides a "gene-centered" (DNA-to-protein) method capable of identifying a collection of TFs that can bind to a DNA fragment of interest. The Y1H assay is therefore complementary to "TF-centered" (protein-to-DNA) methods such as chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)(6), DamID (7) and protein binding microarrays (8) that determine the DNA sequences bound by a protein of interest. While powerful, there are several important conceptual and technical limitations to TF-centered methods (we shall focus on ChIP as it is the most widely used). First, and most importantly, ChIP can only be used for one TF at a time and, thus, the comprehensive identification of a TF binding profile (i.e. the collection of TFs that bind a region of interest) requires performing a ChIP assay for every TF in the system of interest. With hundreds of TFs encoded by eukaryotic genomes, this is as of yet not feasible. Second, the success of ChIP depends on the expression level of the TF (i.e. the more highly or broadly expressed, the more likely it will work in ChIP) as well as the availability of suitable anti-TF antibodies. Currently, only few TFs are amenable to ChIP in most complex eukaryotic organisms and cell systems, making the delineation of TF binding profiles using this technique a daunting task. The Y1H assay does not require antibodies, and every TF is expressed from a plasmid transformed into a yeast strain, so generating TF binding profiles is more feasible using this method. The Y1H assay does, however, have its own set of limitations, including the need to generate TF clone libraries or cDNA libraries, and the possibility that a TF protein may have reduced functionality (e.g. that depend on post-translational modifications) in the yeast system.

TF-DNA interactions can be studied at different scales. For instance, many researchers are interested in how individual genes affect a specific biological process and often use a variety of assays to study the physical interactions in which these genes and their products engage. On the other hand, more and more biologists aim to understand biological processes at a systems level, by connecting large numbers of genes and their products into gene regulatory networks (9). We have developed Y1H assays for the large-scale identification of TF-DNA interactions by combining conventional Y1H assays with recombinational Gateway cloning (10), enabling the processing of large numbers of target DNA sequences (“DNA baits”) simultaneously. We have demonstrated that this system can be efficiently used to generate regulatory networks involving multiple DNA baits and their interactions with many different types of TFs (11–14). However, it is important to note that our Gateway-compatible Y1H system is equally applicable to smaller sets or single DNA fragments of interest.

The protocols in this chapter describe the identification of protein-DNA interactions by screening a cDNA library transformed into a haploid DNA bait strain. While this type of screen is the most popular option because numerous cDNA libraries are commercially available, it should be noted that other technical variations of Y1H are available. For instance, TF clones can be obtained from ORF collections (15, 16) rather than cDNA libraries, and assayed as individual clones (17), multiple small pools of clones (17), or as a TF-only mini-library (10). Further, Y1H assays using individual TF clones can be performed by mating a TF-containing strain with DNA-bait containing strain and detecting the interaction in the resulting diploid yeast (17).

2. Materials

2.1. Yeast Media

Media additives: 3-amino-triazol (3AT, Sigma) 2 M, filter-sterilized, wrapped in aluminum foil and stored at 4°C. Tryptophan (US Biologicals) 40 mM, filter-sterilized, wrapped in aluminum foil and stored at 4°C. Leucine (US Biologicals) 100 mM, stored at room temperature. Histidine (US Biologicals) 100 mM, stored at room temperature. Uracil (US Biologicals) 20 mM, stored at room temperature.

Synthetic complete (Sc) solid media: In one 2 L flask, 2.6 g synthetic complete amino acid mix lacking Ura, His, Trp, Leu (US Biologicals), 3.4 g yeast nitrogen base (US Biologicals), and 10 g ammonium sulfate (US Biologicals) are dissolved in 950 mL water, pH to 5.9 by adding (~3 mL) 10 M NaOH, retain stir bar in flask. In a second 2 L flask 35 g agar is added to 950 mL water. Both flasks are autoclaved for 40 minutes on liquid cycle, the contents of the first flask (including stir bar) is poured into the agar flask, 100 mL autoclaved 40% (w/v) glucose is then added. The mix is cooled to 55°C before adding media additives as required (16 mL of leucine, histine, tryptophan, uracil stock solutions will provide the desired final concentrations). 150 mm sterile Petri dishes require about 80 mL per dish, are dried for 3 to 5 days at room temperature, and stored in air-tight packaging at room temperature for up to 6 months.

YEPD liquid: 10 g yeast extract (US Biologicals), 20 g peptone (US Biologicals) are dissolved in 950 mL water. Autoclave, then add 50 mL sterile 40% (w/v) glucose.

YEPD plates (solid media): In one 2 L flask, 20 g yeast extract (US Biologicals), 40 g peptone (US Biologicals) is dissolved in 950 mL water, retain stir bar in flask. In a second 2 L flask 35 g agar is added to 950 mL water. Both flasks are autoclaved for 40 minutes on liquid cycle, the contents of the first flask (including stir bar) is poured into the agar flask, 100 mL autoclaved 40% (w/v) glucose is added. 150 mm sterile Petri dishes require about 80 mL per dish, are dried for 3 to 5 days at room temperature, and stored in air-tight packaging at room temperature for up to 6 months.

2.2. Generating a DNA Bait Yeast Strain

YM4271 yeast strain (MATa, ura3–52, his3-Δ200, ade2–101, ade5, lys2–801, leu2–3,112, trp1–901, tyr1–501, gal4Δ, gal80Δ, ade5::hisG)

DNA bait::reporter constructs cloned in pMW#2(HIS3) and pMW#3(LacZ)

2.3. High-Efficiency Yeast Transformation

TE buffer (10X): 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA.

TE/LiAc solution: 1× TE buffer, 100 mM lithium acetate (Sigma).

TE/LiAc/PEG solution: 1× TE buffer, 100 mM lithium acetate (Sigma), 40% (w/v) PEG 3350 (Fisher Scientific).

Disposable 250 mL conical flasks (Corning).

Salmon sperm DNA, 10 mg/mL (Invitrogen).

2.4. Yeast Replica Plating

Velvets: 22 cm × 22 cm pieces of velveteen (100% cotton velveteen without rayon). When first cut from a larger sheet of velveteen, velvets need to be washed and dried at least 10 times (without soap) to remove excess lint. After use in replica plating, velvets need to be first autoclaved, then washed without soap and dried, packed in stacks and wrapped in aluminum foil and again autoclaved using a dry cycle.

Replica-plating apparatus (Cora Styles #4006 for 150 mm plates).

2.5. βGal Assay

Z-buffer: 60 mM Na2HPO4.7H2O, 60 mM NaH2PO4.H2O, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4.7H2O, pH to 7.0 with 10 M NaOH, autoclaved, stored at room temperature.

X-gal solution: X-gal (Gold Biotechnology) dissolved at 4% (w/v) in di-methyl formamide (DMF) (in fume hood), wrapped in aluminum foil, stored at −20°C.

Nitrocellulose (NC) filters (45 micron, 137 mm) (Fisher Scientific #WP4HY13750).

Whatman filters, 125 mm, (VWR #1452125).

2.6. Yeast PCR

Zymolyase suspension: 200 mg Zymolase-100T (Associates of Cape Cod Cat. No. 120493-1) is mixed in 100 mL sterile sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) for 30 mins (some precipitate will be visible). 1 mL aliquots are stored at −20°C.

M13F primer (5'-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3').

1H1F primer (5'-GTTCGGAGATTACCGAATCAA-3').

HIS293R primer (5'-GGGACCACCCTTTAAAGAGA-3').

LACZ592R primer (5'-ATGCGCTCAGGTCAAATTCAGA-3').

AD primer (5'-CGCGTTTGGAATCACTACAGGG-3').

TERM primer (5'-GGAGACTTGACCAAACCTCTGGCG-3').

2.7. Y1H Screening an AD-cDNA Library

DNA-bait yeast strain.

AD-cDNA library DNA at a concentration of 1 µg/µL.

3. Methods

3.1. Generating a DNA Bait Yeast Strain

3.1.1. High-Efficiency Yeast Transformation for Integrating Reporter Constructs

Linearize at least 1 µg of the DNA bait pMW#2 reporter construct using one of AflII, XhoI, NsiI or BseR1 in a 25 µl reaction. Similarly linearize at least 1 µg of the DNA bait pMW#3 reporter construct using one of NcoI, ApaI, StuI in a 25 µl reaction (see Note 1).

Using a sterile toothpick or disposable plastic loop, thickly spread YM4271 yeast strain onto 150 mm YEPD plates. Incubate overnight at 30°C.

Using a sterile toothpick or disposable plastic loop resuspend YM4271 into 40 mL liquid YEPD to an OD600 of 0.15–0.20. Remember to also perform steps 3.1.1.3 to 3.1.1.19) for a “no DNA” control.

Incubate the culture in a shaking incubator (30°C, 200 rpm) until the culture reaches an OD600 of 0.4–0.6. This usually takes about 5 hours. However, the culture should be checked regularly (every hour).

Pellet the cells by centrifugation (700 g) in conical tubes at room temperature for 5 minutes.

Prepare at least 20 µL denatured salmon sperm DNA (ssDNA, 10 mg/mL) by boiling for 5 minutes, then keeping on ice.

Discard the liquid from the pellet formed in 3.1.1.5 (the yeast form a firm pellet), and wash the cells with 20 mL sterile water. The cells can be resuspended by pipetting up and down or by shaking the tube. Do not vortex.

Centrifuge the yeast suspension as in 3.1.1.5, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the cells in 5 mL freshly made TE/LiAc solution. Do not vortex.

Centrifuge as in 3.1.1.5, remove the supernatant carefully by aspiration, and then resuspend the cells in 200 µL TE/LiAc solution by pipetting up and down.

Add 20 µL denatured ssDNA to the yeast suspension and mix by pipetting up and down.

Aliquot 200 µL of TE/LiAc/ssDNA bait yeast suspension into a sterile 1.5 mL tube.

Add 20 µl of both linearized constructs from 3.1.1.1 into the same 200 µl of TE/LiAc/ssDNA YM4271 suspension.

Add 1250 µL TE/LiAc/PEG solution to the tube and mix by multiple inversions or by pipetting up and down (do not vortex).

Incubate all transformation reactions for 30 minutes at 30°C (see Note 2).

Heat-shock the cells for exactly 20 minutes at 42°C (in a water bath).

Centrifuge the tubes for one minute at room temperature at 700 g and remove the supernatant by aspiration.

Resuspend the pellet in 500 µL sterile water by pipetting up and down (do not vortex).

Using sterile glass beads, plate the resuspension onto a 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His plate. Do this also for the “no DNA” control.

Incubate all plates at 30°C.

After 3 days, yeast colonies should appear on the integration plate and no colonies should grow on the “no DNA” control. If colonies do appear on the latter plate, there has been a contamination in one of the reagents and the integration should be repeated with new reagents (see Note 3).

3.1.2. Testing Autoactivation of DNA Bait Yeast Strains

Using sterile toothpicks, transfer 12 integrant colonies (see Note 4) from the plate in 3.1.1.20 to a 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His plate in “96-spot format” (Fig. 3). If positive control yeast strains that express known levels of reporters are available, they should also be transferred to these plates (Fig. 3). Incubate the plates at 30°C for 1 to 2 days.

Replica-plate (see Note 5) the yeast from 3.1.2.1 onto several 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His plates, each containing a different concentration of 3AT (0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80 mM) (see Note 6), and a 150 mm YEPD plate onto which a nitrocellulose (NC) filter has been placed (so that the yeast will grow on the filter). Replica-clean (see Note 5) the plates containing 3AT and incubate them for 5 days at 30°C. Incubate the other two plates overnight at 30°C. The Sc-Ura,-His plate without 3AT is used to maintain the integrants and can be stored at room temperature for 14 days. The NC filter/YEPD plate is used for the βGal assay (steps 3 to 7 below).

For each NC filter/YEPD plate to be analyzed, place two Whatman filters in an empty 150 mm Petri dish. Move to a fumehood for the next three steps.

For each Petri dish in 3.1.2.3, set up a reaction mix containing 6 mL Z-buffer, 11 µL β-mercapto-ethanol, and 100 µL X-gal solution (see Note 7). Use this entire mix to soak the Whatman filters, and remove any air bubbles using forceps to lift the filters and squeeze the bubbles to the sides, then remove excess liquid into a waste bottle by tipping the plate.

Lift the NC filter from the YEPD plate using forceps and place the filter yeast side up in a liquid nitrogen bath for 10 seconds. Discard the YEPD plate.

Use the forceps to place the frozen NC filter with the yeast facing up onto the wet Whatman filters from 3.1.2.4, and use forceps (or a needle) to remove air bubbles under the NC filter quickly as the NC filter (and yeast lysate) thaws.

Incubate each βGal assay plate at 37°C overnight. Record the amount of blue compound generated by each yeast lysate.

Observe the amount of growth each integrant displays after 5 days on the Sc-Ura,-His plates containing 3AT (3.1.2.2), recording how much 3AT was required to inhibit the growth of each integrant strain.

Choose 1 to 4 integrant strains showing the lowest autoactivity for both reporters (see Note 8).

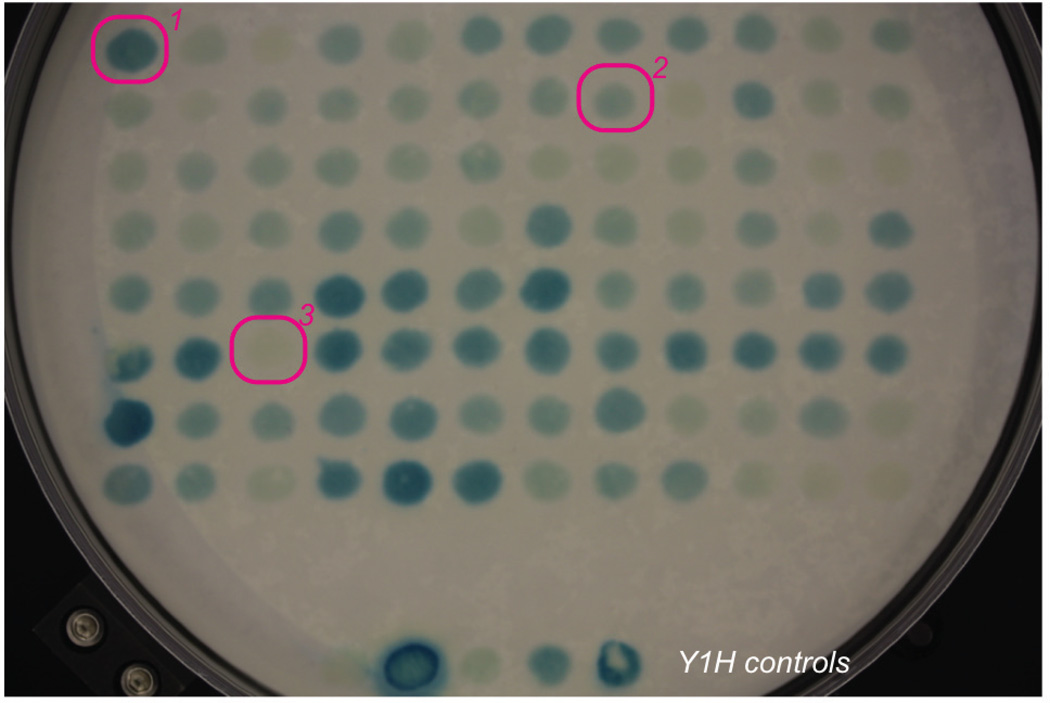

Fig. 3.

Example of 96-spot LacZ assay. 1 – strong Y1H positive; 2 – weak Y1H positive; 3 – Y1H negative.

3.1.3: Yeast PCR to Confirm DNA Bait Identity

Using a sterile toothpick, transfer the chosen yeast from 3.1.2.9 to a fresh YEPD plate (see Note 9). Incubate overnight at 30°C.

For each integrant to be analyzed, aliquot 15 µL zymolyase suspension into a sterile PCR tube or the wells of a 96-well PCR plate (see Note 10).

Using a sterile toothpick or pipette tip, transfer a small amount (approximately one-fourth the size of a match head) of each yeast colony to its own zymolyase aliquot. Too much yeast will inhibit the PCR reaction.

Transfer the PCR tubes/plate to a thermal cycler and incubate the yeast-enzyme mix for 30 minutes at 37°C, then heat-inactivate the enzyme for 10 minutes at 95°C.

Remove the PCR tubes/plate from the thermal cycler and dilute each lysate by adding 85 µL sterile PCR-grade water. The lysates can be stored at −20°C for up to 1 year for subsequent PCR reactions.

For each lysate prepare two PCR reactions, one for the HIS3 construct and one for the LacZ construct (see Note 11). HIS3: 5 µL diluted lysate, 1 µL M13F primer (20 µM), 1 µL HIS293R primer (20 µM), 5 µL dNTPs (1 mM), 5 µL PCR buffer (10×), 2 units Thermostable DNA polymerase, PCR-grade water to total reaction volume of 50 µL. LacZ: 5 µL diluted lysate, 1 µL 1H1F primer (20 µM), 1 µL LAC592R primer (20 µM), 5 µL dNTPs (1 mM), 5 µL PCR buffer (10×), 2 units Thermostable DNA polymerase, PCR-grade water to total reaction volume of 50 µL.

Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following PCR progam: (i) 94°C for 2 minutes, (ii) 94°C for 1 minute, (iii) 56°C for 1 minute, (iv) 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of DNA bait, (v) Repeat steps ii to iv 34 times, (vi) 72°C for 7 minutes. The conditions of the PCR reaction may need to be optimized.

Run 5–10 µL of the PCR reaction on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel in 1XTBE alongside DNA molecular weight markers (see Note 12).

Use the appropriate forward primer to sequence each PCR product that is the expected size. Maintain the integrant strains on either YEPD or Sc-His,-Ura plates while waiting for sequence results (the yeast will need to be transferred to fresh media every two weeks).

Using a sterile toothpick, transfer the integrants that have the correct DNA bait in both reporter constructs to a fresh Sc-Ura,-His plate and incubate the plate at 30°C overnight. Only one integrant strain per DNA bait is needed for library screens but it is useful to have at least one backup strain.

Using a sterile toothpick, transfer a match-head-sized amount of this freshly grown yeast into 200 µl of sterile 15% (v/v) glycerol solution. Vortex the yeast/glycerol solution for 5 seconds and store the resulting yeast suspension at −80°C. These frozen yeast stocks can be revived by transferring some (~5 µl) of the frozen stock to a YEPD plate and allowing growth at 30°C for at least 2 days.

3.2. Y1H Screening an AD-cDNA Library

3.2.1. High-Efficiency Yeast Transformation with an AD-cDNA Library

Using a sterile toothpick or disposable plastic loop, thickly spread the DNA bait yeast strain onto YEPD plates (see Note 9). Incubate overnight at 30°C.

Using a sterile toothpick or disposable plastic loop resuspend the bait strain into 400 mL liquid YEPD to an OD600 of 0.15–0.20.

Incubate the culture in a shaking incubator (30°C, 200 rpm) until the culture reaches an OD600 of 0.4–0.6. This usually takes about 5 hours. However, the culture should be checked regularly (every hour).

Pellet the cells by centrifugation (700 g) in conical 250 ml tubes at room temperature for 5 minutes.

Prepare at least 200 µL denatured salmon sperm DNA (ssDNA, 10 mg/mL) by boiling for 5 minutes, then keeping on ice.

Discard the liquid from the pellet formed in 3.2.1.4 (the yeast form a firm pellet), and wash the cells with 40 mL sterile water. The cells can be resuspended by and pipetting or by shaking the tube. Do not vortex.

Centrifuge the yeast suspension as in 3.2.1.4, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the cells in 8 mL freshly made TE/LiAc solution. Do not vortex.

Centrifuge as in 3.2.1.4, remove the supernatant carefully by aspiration, and then resuspend the cells in 2 mL TE/LiAc solution by pipetting up and down.

Add 200 µL denatured ssDNA to the yeast suspension and mix by pipetting up and down.

Aliquot 2 mL of TE/LiAc/ssDNA bait yeast suspension into a sterile 15 mL tube, 30 µL into a sterile 1.5 mL tube, and 100 µL into another sterile 1.5 mL tube.

Add 30 µg of AD-cDNA library (e.g. 30 µL of a 1 µg/µL solution) to the 2 mL of TE/LiAc/ssDNA bait yeast suspension, then add 10.5 mL freshly made TE/LiAc/PEG solution, and mix by multiple inversions or pipetting up and down (do not vortex). Aliquot this yeast/library/PEG mix into 12 sterile 1.5 mL tubes (see Note 13).

Add 50 ng empty library plasmid to the 30 µL TE/LiAc/ssDNA bait yeast suspension, then add 175 µL TE/LiAc/PEG solution, and mix by pipetting up and down (do not vortex).

Add 500 µL TE/LiAc/PEG solution to the tube containing 100 µL of TE/LiAc/ssDNA bait yeast suspension, and mix by multiple inversions or by pipetting up and down (do not vortex).

Incubate all transformation reactions for 30 minutes at 30°C (see Note 2).

Heat-shock the cells for exactly 20 minutes at 42°C (in a water bath).

Centrifuge the tubes for one minute at room temperature at 700 g and remove the supernatant by aspiration.

Resuspend the pellet in each of the cDNA library transformation tubes (3.2.1.11) in 500 µL sterile water by pipetting up and down (do not vortex). Take 5 µL of the library transformation mix from one of these tubes and mix with 495 µL of sterile water to create a 1:100 dilution. Take 50 µL from the 1:100 dilution and add 450 µL sterile water to create a 1:1000 dilution. Use sterile glass beads to spread the dilutions onto 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plates (see Note 14). These plates will be used to determine the transformation efficiency of the reactions.

Using sterile glass beads, plate the remainder of the library transformation across twelve 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp + 3AT plates. Multiple large media plates are needed to ensure the growth of well-separated colonies (see Note 15).

Resuspend the “empty plasmid” control yeast transformation reaction (3.2.1.12) in 30 µL sterile water by pipetting up and down (do not vortex). Pipette 5 µL of this suspension as a single spot onto a Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate. This yeast transformed with empty library vector will be used later as the “negative control” for the assessment of interactions retrieved from the cDNA library.

Resuspend the “no DNA” control yeast transformation (3.2.1.13) in 500 µL sterile water by pipetting up and down (do not vortex). Use sterile glass beads to spread this suspension onto a single 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate.

Incubate all plates at 30°C.

After 3 days, yeast colonies should appear on the empty plasmid (3.2.1.19) and transformation efficiency determination (3.2.1.17) plates and no colonies should grow on the no DNA control (3.2.1.20). If colonies do appear on the no DNA control plate, the screen cannot be used as there has been a contamination in one of the reagents. The plate with empty plasmid yeast can be stored at room temperature until needed.

Calculate the transformation efficiency (number of colonies per microgram of DNA) using the plated dilutions from 3.2.17 (see Note 16).

If the transformation was successful, the plates from 3.2.18 can be incubated at 30°C for up to 14 days. Check the plates regularly for appearing colonies and pick “HIS-positive” colonies using a sterile toothpick to transfer to a 150 mm Sc-Ura-His-Trp plate (see Note 17). This plate of selected colonies can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days, or at 4°C for a few weeks.

3.2.2. Identifying “Double-Positive” Transformants

Using sterile toothpicks, transfer “HIS-positive” colonies from the plate(s) from 3.2.1.24 to a new 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate in “96-spot format” (Fig. 3). Also transfer some of the empty plasmid control yeast from 3.2.1.19 to these plates--these will be used later to judge reporter gene induction. If positive control yeast strains that express known levels of reporters are available, they should also be transferred to these plates. Incubate the plates at 30°C for 1 to 2 days.

Replica-plate (see Note 5) the yeast from 3.2.2.1 onto a fresh 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate, a 150 mm Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate containing the 3AT concentration used for screening, and a 150 mm YEPD plate onto which a nitrocellulose (NC) filter has been placed (so that the yeast will grow on the filter). Replica-clean (see Note 5) the plate containing 3AT and incubate this plate for 5 to 10 days at 30°C (to confirm the “HIS-positive” result). Incubate the other two plates overnight at 30°C. The Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate is used to maintain the transformants and can be stored at room temperature for 14 days. The NC filter/YEPD plate is used for the βGal assay (3.1.2.3 to 3.1.2.6).

Check the βGal assays for blue coloring regularly during the 37°C incubation (every hour if necessary) over a maximum 24 hour period. Pictures should be taken that demonstrate the amount of blue compound generated by each yeast lysate. For baits that display moderate to high LacZ expression in the absence of a TF, it may be necessary to compare potential positive yeast to the empty plasmid controls often to see increased reporter expression.

Double-positive yeast will exhibit both growth on 3AT-containing media (3.2.2.2) and blue coloring in the βGal assay (3.2.2.3) that is greater than the yeast transformed with empty plasmid (see Note 18).

3.2.3. Gap-Repair Retesting of Interactions

Transfer “double-positive” yeast from 3.2.2.4 to a fresh Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate(s) with a sterile toothpick, and incubate overnight at 30°C (see Note 19).

For each positive yeast generate a lysate for yeast PCR (3.1.3.2 to 3.1.3.5)

For each amplification, in a sterile PCR tube (or well of a PCR plate) prepare the following PCR reaction mix: 5 µL diluted lysate, 1 µL AD primer (20 µM), 1 µL TERM primer (20 µM), 5 µL dNTPs (1 mM), 5 µL PCR buffer (10×), 2 units Thermostable DNA polymerase, PCR-grade water to total reaction volume of 50 µL (see Note 11).

Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following PCR progam: (i) 94°C for 2 minutes, (ii) 94°C for 1 minute, (iii) 56°C for 1 minute, (iv) 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of average library insert size, (v) Repeat steps ii to iv 34 times, (vi) 72°C for 7 minutes. The conditions of the PCR reaction may need to be optimized.

Run 5–10 µL of the PCR reaction on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel in 1XTBE alongside DNA molecular weight markers. The PCR products can be stored at −20°C. Only PCR reactions that amplify a single band can be used in later steps (see Note 20).

In a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube set up the following restriction endonuclease digest: 10 µg pPC86 plasmid, 4 µL Bovine Serum Albumin (1 mg/mL), 4 µL RestrictionBuffer (10×), 2 µL (20 units) SalI, 2 µL (20 units) BglII, PCR-grade water to a final volume of 40 µL. Mix the digest and incubate overnight at 37°C (see Note 21).

Using steps 3.2.1.1 to 3.2.1.9, prepare 2.2 mL of TE/LiAc/ssDNA bait yeast suspension. This will be enough yeast suspension for 96 transformations performed in a 96-well PCR plate.

To each well, aliquot 20 µL TE/LiAc/ssDNA yeast suspension, and add 5 µL prey PCR product (from 3.2.3.5) and 40 ng linear pPC86 (from 3.2.3.6). Three negative controls without PCR product should be included: no DNA, 40 ng of linear pPC86 alone, and 40 ng of circular (i.e. undigested) pPC86.

Add 150 µL freshly made TE/LiAc/PEG solution to each well and mix by pipetting up and down.

Incubate the PCR plate for 30 minutes at 30°C using a PCR machine or water bath (see Note 2).

Heat-shock the cells for exactly 20 minutes at 42°C using a PCR machine or water bath.

Centrifuge the tubes for one minute at room temperature (700 g) and remove the supernatant by careful aspiration.

Resuspend each well of yeast in 20 µL sterile water by pipetting up and down. Pipette 3 µL of each suspension as a single spot onto a Sc-Ura,-His,-Trp plate in “96-spot format” (Fig. 3). If positive control yeast strains that express known levels of reporters are available, they should also be transferred to these plates (Fig. 3). Incubate the plates at 30°C.

After 3 days, yeast colonies should have appeared. The number of transformants should be an order of magnitude higher in gap-repair samples and uncut pPC86 controls compared to the linear pPC86 alone control. No transformants should be present in the no DNA control (see Note 22).

Use step 3.2.2.2 with the yeast media plate from 3.2.3.14 to identify double-positive transformants.

Determine the identity of these double-positive preys that retest by gap-repair by sequencing the PCR products generated in 3.2.3.5 using the AD primer (see Note 23).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the Walhout lab for comments and advice. This work was supported by NIH grants R01DK068429 and R01GM082971.

Footnotes

This protocol assumes that the DNA bait::reporter constructs have been generated by Gateway cloning in pMW#2 and pMW#3 (10). The restriction enzyme of choice must not cut within the DNA bait sequence. These digests linearize the Y1H reporter constructs such that regions of homology to the yeast genome occur at both ends. When these linear constructs are transformed into the yeast strain, the pMW#2 construct is integrated into the mutant HIS3 locus (his3-Δ200) of the host strain YM4271, while the pMW#3 construct is integrated into the mutant URA3 locus (ura3–52). If alternate reporter constructs are used, restriction digests that result in a conceptually similar DNA molecule must be performed.

This incubation step can continue for up to 4 hours, but the transformation efficiency is greatly reduced if this incubation step is less than 30 minutes or more than 4 hours.

If the entire transformation is spread onto a single 100 mm plate, the integrants will have difficulty growing due to the presence of untransformed yeast – if 100 mm plates are used, spread each transformation over at least three plates. Both Y1H reporter constructs are integrative (YIp) vectors that cannot be replicated within yeast, so any colonies that grow at this stage must be integrants. The number of colonies obtained usually varies between 10 and 100. If no integrants arise, a first option to try is to repeat the transformation with more linear DNA, a second option is to integrate the reporters sequentially instead of simultaneously (i.e. integrate the LacZ reporter first, pick a low autoactive integrant [see below] then integrate the HIS3 reporter into this strain).

Autoactivity is the level of expression of integrated DNA bait::reporters in the absence of an AD-prey clone. The cause of autoactivation is likely due to an endogenous yeast activator binding the DNA bait. It has also been observed that different integrant strains arising from the same transformation can show varying levels of autoactivity, which may be because differing numbers of DNA bait::reporter cassettes have been integrated into each strain (and even at each locus within each strain)(10). It is important to select the integrant with lowest autoactivity for both reporters for subsequent Y1H assay so that TF-DNA interactions are easily retrieved and retested. To achieve this, multiple integrants need to be tested for autoactivation per DNA bait.

Replica-plating: A sterile velvet is placed (velvet side up) onto the replica-plating block and locked into place using the collar. The yeast plate is placed yeast side down onto the velvet and evenly pressed to transfer the yeast from the plate to the velvet. Plates should be marked to maintain orientation. The yeast plate is then removed, and a new plate is placed media side down onto the velvet and pressed evenly to transfer the yeast from the velvet to the new plate. Multiple (up to five) transfers can be performed in this way from a single velvet. Sometimes “replica-cleaning” of the new plate is required. Replica-cleaning involves pressing the plate onto a series of sterile velvets (used only once) to remove excess yeast that can interfere with the observation of actively growing yeast--usually two or three velvets are required.

3AT is a competitive inhibitor of the His3 enzyme, and is used in Y1H assays to quench HIS3 autoactivity.

The LacZ reporter expresses the enzyme βGalactosidase (βGal) that converts clear X-gal into a blue compound that is observed in this colorimetric assay (Fig. 3).

Both reporter constructs contain a minimal promoter so all integrant strains should both generate a little blue compound in the colorimetric assay (Fig. 3), and confer growth on media containing a little 3AT. If no blue compound at all is observed, or no growth even on 10 mM 3AT plates is observed, this may indicate a problem with either reporter construct and such integrants should not be selected if possible. The lowest concentration of 3AT that totally prevents growth should be used for library screens (i.e. integrants that grow on 20 mM 3AT but not on 40 mM 3AT should be screened at 40 mM). Integrants that grow strongly on 80 mM 3AT cannot be used in Y1H library screens because few (if any) protein-DNA interactions can activate the HIS3 reporter enough to overcome this high background, and because higher concentrations of 3AT are toxic to yeast. However, integrants with low HIS3 autoactivity and high LacZ autoactivity can be screened because interactions are detected by growth assay using the HIS3 reporter first and the LacZ activity in these “HIS-positive” yeast may be higher than background when observed closely. However, results obtained with highly autoactive baits should be judged with caution (see 3.2.2.4). Note that for some DNA baits (10–20%) the autoactivity levels for all integrants will be too high, making Y1H screens impossible. For these highly autoactive DNA baits it may be desirable to use smaller fragments of the DNA bait that confer lower autoactivity.

DNA bait strains can be grown on YEPD rich media because the reporter constructs are integrated in the genome, and so the selection of the reporter constructs on media lacking histidine and uracil is not required once a DNA bait strain has been generated, verified and examined for autoactivation.

Because zymolyase has low solubility in water, it is important to mix the suspension thoroughly before, and periodically (every 30 seconds) during distribution into the tubes/wells.

Remember to include a negative control PCR reaction that lacks template. For PCR reactions from yeast lysates we recommend Invitrogen Taq DNA Polymerase (Cat. No. 10342-053).

The HIS3 construct primers add about 400 bp to the amplicon, the LacZ construct primers add about 800 bp to the amplicon.

The amount of library listed here is for a C. elegans cDNA library of 4×107 clones, representing ~16,000 of the ~20,000 genes, in the non-Gateway pPC86 plasmid (18). This amount should be adjusted if using a higher- or lower-complexity library.

Tryptophan is omitted from the media because the TF-expressing plasmids contain a TRP1 selection marker, and thus, only transformed DNA bait yeast will grow on this media.

The concentration of 3AT in these plates should be based on the autoactivation results in 3.1.2.9 such that growth of DNA bait yeast not demonstrating reporter activation is minimal.

For relatively simple eukaryotes, an effective library screen involves testing (i.e. transforming) at least one million clones, with higher clone numbers increasing the chance of finding interactions involving less abundant TFs. For more complex organisms such as humans that have more splice variants and tissues, it may be desired to screen more colonies. The number of colonies to be screened also depends on the complexity of the cDNA library. If fewer than one million colonies were obtained, the screen may need to be repeated until the required number of colonies is attained. The transformation efficiency depends on the condition of the yeast strain; use only freshly grown bait yeast strains, do not vortex any yeast suspensions and only use solutions at room temperature. The amount and quality of plasmid DNA being transformed is also important, so preparation of library DNA should involve an ethanol precipitation to remove contaminants and the concentration should be determined by spectrophotometry. If no colonies grew at all, the media may have been incorrectly prepared (e.g. no glucose was added, or wrong media).

The number and size of colonies obtained varies greatly and depends on the DNA bait used. Different TFs can confer different Y1H interaction phenotypes, so it is important to select larger and smaller colonies where feasible. Some bait strain transformations may not yield any colonies on the library screen plates (3.2.1.18) despite good transformation efficiency (3.2.1.17)--such baits may be screened again, perhaps using media with lower concentrations of 3AT or using a different cDNA library (e.g. obtained with mRNA from another tissue/source). However, it is possible that some bait strains may yield many hundreds of colonies. Such DNA baits may be interacting with many partners, or they interact with a highly abundant protein that is overrepresented in the library (this latter issue is particularly relevant for non-normalized cDNA libraries). Alternatively, these baits may need to be screened again using media with higher concentrations of 3AT.

If the bait is moderately autoactive, only clones that confer reporter gene expression that is clearly much higher than background should be considered. If the bait is highly autoactive, it may be extremely difficult to identify clear interactions and the bait may need to be redesigned.

It is necessary to retest every interaction identified from a cDNA library screen because some of the “double-positive” yeast phenotypes may not be due to the AD-prey interacting with the bait, but arise when bait yeast turn into (i.e. de novo) autoactivators (19). This is when a small number of individual yeast from a population with generally low autoactivity levels exhibit high reporter activation due to mutations induced either by PCR (when initially cloning the bait) or during propagation of the yeast. When de novo autoactivators occur in screens, they will appear as positive colonies. The easiest method to confirm protein-DNA interactions is by gap-repair. Gap-repair involves using PCR to amplify the ORF from the pPC86 clone in each positive yeast colony, then co-transforming each amplicon with linear empty pPC86 vector into fresh bait strain yeast. Homologous recombination within the yeast reconstitutes the vector and insert into a new construct, and reporter activation within the resulting transformed yeast is re-assayed. Without gap-repair, every interaction would need to be confirmed by transforming the AD-prey construct into fresh yeast, and while extracting the plasmid from the double-positive yeast for such a transformation is technically possible, it is challenging to do this for many interactions simultaneously.

At either end of these PCR products is about 100 bp of sequence matching the vector sequence on either side of the pPC86 multi-cloning site. These sequences will facilitate homologous recombination. Some of each amplicon will be used for the gaprepair retest, and the remainder will be used for DNA sequencing. Therefore, yeast lysates that generate multiple PCR bands likely contain multiple AD-prey clones, and will not give clean sequence data to identify the interacting protein.

This digest excises a small (~20 bp) fragment from the multi-cloning site of the vector resulting in a linear fragment with non-compatible ends. If the library of choice is not pPC86-based then restriction enzymes should be chosen for the appropriate vector that results in the same type of linear fragment. There is no need to purify the linear plasmid backbone from the digestion mix.

If the gap-repair samples failed to generate more colonies than the linear vector control first check the number of colonies produced by the uncut vector control. If the linear vector gave the same number of colonies as the uncut vector, this suggests that the original sample was not fully digested, and new linear vector needs to be generated. If some of the gap-repair transformations failed to generate more colonies than the linear vector control it is likely there was not enough PCR product in the transformation. For these samples, extra (up to 20 µL) PCR reaction can be transformed or some (0.5 µL) can be used as template in an additional PCR reaction to generate a higher amount of PCR product. If no colonies appear, it is likely that the media is incorrect.

Verify that the preys are in frame with the Gal4 AD; if not, a spurious peptide may be responsible for the interaction phenotype. Proteins that are retrieved multiple times likely represent real interactions, at least in the context of the Y1H assay. However, proteins that were identified only once should not be excluded because some TFs may be present at low copy numbers in the cDNA library and are therefore more difficult to retrieve than abundant TFs, particularly since Y1H screens are rarely saturating. In Y1H screens between zero and 40 interacting proteins can be observed with a single DNA bait (11–14). The majority (>95%) of retrieved proteins will be predicted regulatory TFs. However, proteins without a predicted DNA binding domain can constitute a small proportion (~5%) of interactors. These proteins may possess a novel type of DNA binding domain, or may interact with DNA baits indirectly (11, 12).

Contributor Information

John S. Reece-Hoyes, Email: john.reece-hoyes@umassmed.edu.

Albertha J.M. Walhout, Email: marian.walhout@umassmed.edu.

References

- 1.Wang MM, Reed RR. Molecular cloning of the olfactory neuronal transcription factor Olf-1 by genetic selection in yeast. Nature. 1993;364:121–126. doi: 10.1038/364121a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li JJ, Herskowitz I. Isolation of the ORC6, a component of the yeast origin recognition complex by a one-hybrid system. Science. 1993;262:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.8266075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walhout AJM, Sordella R, Lu X, Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA, Thierry-Mieg N, Vidal M. Protein interaction mapping in. C. elegans using proteins involved in vulval development. Science. 2000;287:116–122. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5450.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rual JF, Venkatesan K, Hao T, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Dricot A, Li N, Berriz GF, Gibbons FD, Dreze M, Ayivi-Guedehoussou N, Klitgord N, Simon C, Boxem M, Milstein S, Rosenberg J, Goldberg DS, Zhang LV, Wong SL, Franklin G, Li S, Albala JS, Lim J, Fraughton C, Llamosas E, Cevik S, Bex C, Lamesch P, Sikorski RS, Vandenhaute J, Zoghbi HY, Smolyar A, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Roth FP, Vidal M. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren B, Robert F, Wyrick JJ, Aparicio O, Jennings EG, Simon I, Zeitlinger J, Schreiber J, Hannett N, Kanin E, Volkert TL, Wilson CJ, Bell SP, Young RA. Genome-wide location and function of DNA binding proteins. Science. 2000;290:2306–2309. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Steensel B, Delrow J, Henikoff S. Chromatin profiling using targeted DNA adenine methyltransferase. Nat Genet. 2001;27:304–308. doi: 10.1038/85871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger MF, Philippakis AA, Qureshi AM, He FS, Estep PW, 3rd., Bulyk ML. Compact, universal DNA microarrays to comprehensively determine transcription-factor binding site specificities. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1429–1435. doi: 10.1038/nbt1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walhout AJM. Unraveling transcription regulatory networks by protein-DNA and protein-protein interaction mapping. Genome Res. 2006;16:1445–1454. doi: 10.1101/gr.5321506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deplancke B, Dupuy D, Vidal M, Walhout AJM. A Gateway-compatible yeast one-hybrid system. Genome Res. 2004;14:2093–2101. doi: 10.1101/gr.2445504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deplancke B, Mukhopadhyay A, Ao W, Elewa AM, Grove CA, Martinez NJ, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stam L, Reece-Hoyes JS, Hope IA, Tissenbaum HA, Mango SE, Walhout AJM. A gene-centered. C. elegans protein-DNA interaction network. Cell. 2006;125:1193–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vermeirssen V, Barrasa MI, Hidalgo C, Babon JAB, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stam L, Barabasi AL, Walhout AJM. Transcription factor modularity in a gene-centered. C. elegans core neuronal protein-DNA interaction network. Genome Res. 2007;17:1061–1071. doi: 10.1101/gr.6148107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez NJ, Ow MC, Barrasa MI, Hammell M, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Roth FP, Ambros V, Walhout AJM. A. C. elegans genome-scale microRNA network contains composite feedback motifs with high flux capacity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2535–2549. doi: 10.1101/gad.1678608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arda HE, Taubert S, Conine C, Tsuda B, Van Gilst MR, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stam L, Yamamoto KR, Walhout AJM. Functional modularity of nuclear hormone receptors in a C. elegans gene regulatory network. Molecular Systems Biology in press. 2010 doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reboul J, Vaglio P, Rual JF, Lamesch P, Martinez M, Armstrong CM, Li S, Jacotot L, Bertin N, Janky R, Moore T, Hudson JR, Jr., Hartley JL, Brasch MA, Vandenhaute J, Boulton S, Endress GA, Jenna S, Chevet E, Papasotiropoulos V, Tolias PP, Ptacek J, Snyder M, Huang R, Chance MR, Lee H, Doucette-Stamm L, Hill DE, Vidal M. C. elegans ORFeome version 1.1: experimental verification of the genome annotation and resource for proteome-scale protein expression. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:35–41. doi: 10.1038/ng1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rual J-F, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Hao T, Bertin N, Li S, Dricot A, Li N, Rosenberg J, Lamesch P, Vidalain P-O, Clingingsmith TR, Hartley JL, Esposito D, Cheo D, Moore T, Simmons B, Sequerra R, Bosak S, Doucette-Stam L, Le Peuch C, Vandenhaute J, Cusick ME, Albala JS, Hill DE, Vidal M. Human ORFeome version 1.1: a platform for reverse proteomics. Genome Res. 2004;14:2128–2135. doi: 10.1101/gr.2973604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermeirssen V, Deplancke B, Barrasa MI, Reece-Hoyes JS, Arda HE, Grove CA, Martinez NJ, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Brent M, Walhout AJM. Matrix and Steiner-triple-system smart pooling assays for high-performance transcription regulatory network mapping. Nat Methods. 2007;4:659–664. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walhout AJM, Temple GF, Brasch MA, Hartley JL, Lorson MA, van den Heuvel S, Vidal M. GATEWAY recombinational cloning: application to the cloning of large numbers of open reading frames or ORFeomes. Methods in enzymology: “Chimeric genes and proteins”. 2000;328:575–592. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walhout AJM, Vidal M. A genetic strategy to eliminate self-activator baits prior to high-throughput yeast two-hybrid screens. Genome Res. 1999;9:1128–1134. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.11.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]