Abstract

Background

Elevations or deficits in thyroid hormone levels are responsible for a wide range of neonatal and adult phenotypes. Several genome-wide, candidate gene and meta-analysis studies have examined thyroid hormones in adults; however, to our knowledge no genetic association studies have been performed with neonatal thyroid levels.

Methods

A population of Iowa neonates; term (n=827) and preterm (n=815), were genotyped for 45 single nucleotide polymorphisms. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) values were obtained from the Iowa Neonatal Metabolic Screening Program. Analysis of variance was performed to identify genetic associations with TSH concentrations.

Results

The strongest association was rs4704397 in the PDE8B gene (p=1.3×10−4), followed by rs965513 (p=6.4×10−4) on chromosome 9 upstream of the FOXE1 gene. Both of these SNPs met statistical significance after correction for multiple testing. Six other SNPs were marginally significant (p<0.05).

Conclusions

We demonstrated for the first time two genetic associations with neonatal TSH levels that replicate findings with adult TSH levels. These SNPs should be considered as early predictors of risk for adult diseases and conditions associated with thyroid hormone levels. Furthermore, this provides a better understanding of the thyroid profile and potential risk for thyroid disorders in newborns.

Introduction

Endocrine disorders are substantial contributors to neonatal morbidity and mortality and, of these, congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is the most common (1). CH is a common and preventable cause of mental retardation with an incidence rate of approximately 1 in 2,350 live births (2). Early treatment with thyroxine (T4) with subsequent supplementation for life produces excellent results for both growth and development (2, 3). CH is screened for at birth through detection of T4, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), or both (3).

In the preterm infant, thyroid function undergoes postnatal changes related to an immature hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA), along with the interrupted exposure to maternal thyroid hormone and thyroid releasing hormone from the placenta. Due to immature HPA function T4 is lower in preterm infants compared to neonates born at term, and there is a direct correlation between the serum T4 level and the degree of prematurity (4). Preterm neonates with abnormal thyroid function may have transient hypothyroxinemia of prematurity, and be misreported as true cases of CH (2). Hence, it is essential to take gestational age and birth weight into consideration when making the differentiation between transient hypothyroidism and true cases of CH (2).

Among healthy subjects, TSH shows considerable variability between individuals, whereas this variability is much less in the same individual when TSH is measured repeatedly over an extended period of time (5). Previous studies have observed that TSH variability is under strong genetic regulation; studies have estimated heritability of up to 65% for variation in adult serum TSH (6). In addition, there have been several genome wide association studies (GWAS) reporting multiple genetic variants associated with TSH levels in adults (5, 7–9). Furthermore in candidate gene studies the Asp727Glu polymorphism in the TSH receptor gene (TSHR) is associated with adult serum TSH levels, which further supports a genetic contribution in assessing the variation of TSH (10). To our knowledge no studies have examined candidate SNPs with neonatal TSH measurements. We genotyped term and preterm infants for 45 SNPs in 24 candidate genes that are known to play a role in TSH production or metabolism and examined these polymorphisms for associations with TSH levels measured at birth as part of the Iowa Neonatal Metabolic Screening Program. Understanding variation in TSH levels and the genes responsible may be particularly important in a population at risk for abnormal TSH levels such as preterm infants.

Results

Analysis was performed on a total of 1,583 neonates (404 University of Iowa State Hygienic Laboratory (SHL) preterm neonates, 799 term neonates, and 380 University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) neonates) (Table 1). The three cohorts were not statistically different from each other when comparing their gender (Table 1). Differences between mean TSH level, gestational age, and birth weight were statistically significant between all three cohorts (Table 1). Difference in mean for age at screening was statistically significant between SHL preterm and NICU preterm but not between SHL term and SHL preterm cohorts (Table 1). Difference in total parenteral nutrition was statistically significant between SHL term and SHL preterm but not between SHL preterm and NICU preterm cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of cohorts

| SHL term (N=799) |

SHL preterm (N=404) |

NICU preterm (N=380) |

P-valuea | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSH level (mIU/l) | 8.9±4.5 | 7.4±4.5 | 5.9±3.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 454 (56.8%) | 230 (56.9%) | 222 (58.4%) | 0.97 | 0.67 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 40.0±0 | 34.0±2.6 | 31.2±3.1 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3,489.9±434.0 | 2,405.1±695.3 | 1,773.4±712.3 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Age at screening (hr) | 36.4±10.6 | 37.6±12.8 | 29.5±7.0 | 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 2 (0.3%) | 51 (12.6%) | 38 (10.0%) | <0.001 | 0.25 |

P-values for differences between SHL term and SHL preterm

P-values for differences between SHL preterm and NICU preterm

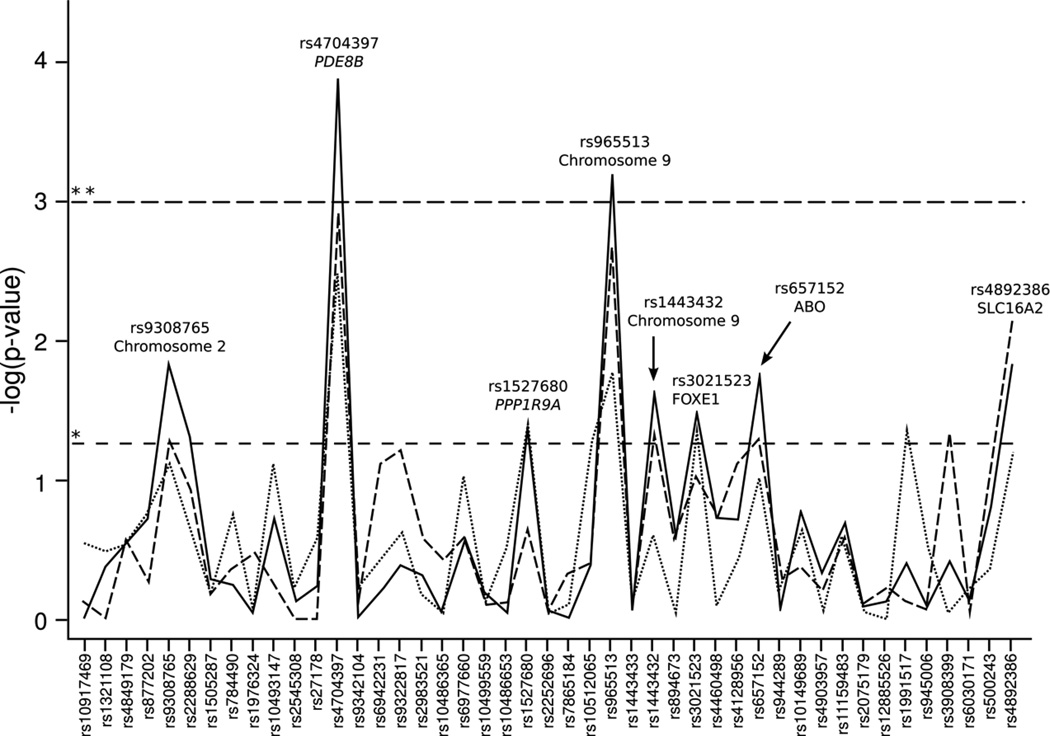

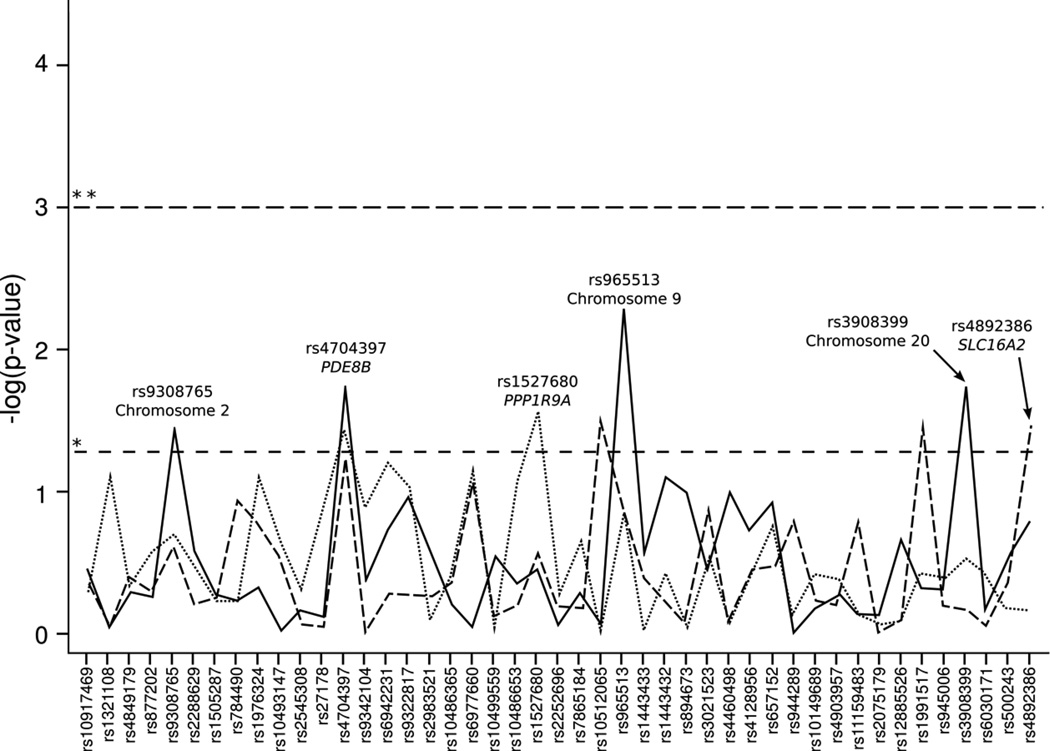

Association results for all genotyped single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in combined populations are shown in Figure 1 and Supplemental Table S1 (online). Association results for all genotyped SNPs in individual populations are shown in Figure 2 and Supplemental Table S2 (online).

Figure 1.

Association statistics for all genotyped SNPs with neonatal TSH level for combined populations. The X-axis is a list of all genotyped markers. The Y-axis is the −log10 of the p-value from the ANOVA analysis. The horizontal dashed lines represent the p-value cutoffs; * p-value = 0.05, ** p-value = 0.001. The solid line is for all populations combined. The dashed line is for the SHL preterm and SHL term combined. The dotted line is for the SHL preterm and the NICU preterm combined.

Figure 2.

Association statistics for all genotyped SNPs with neonatal TSH level for individual populations. The X-axis is a list of all genotyped markers. The Y-axis is the −log10 of the p-value from the ANOVA analysis. The horizontal dashed lines represent the p-value cutoffs; * p-value = 0.05, ** p-value = 0.001. The solid line is for the SHL term population. The dashed line is for the SHL preterm population. The dotted line is for the NICU preterm population.

Eight SNPs were nominally significantly associated with neonatal TSH levels in all study populations combined (p<0.05) (Table 2, Supplemental Table S3, online, and Figure 1).The strongest association was rs4704397 in the PDE8B gene (p=1.3×10−4), followed by rs965513 (p=6.4×10−4) on chromosome 9 upstream of the FOXE1 gene. Both of these SNPs met statistical significance after correction for multiple testing (corrected significance threshold set at p<0.001). While none of the associations in the individual populations met the significance threshold after correction for multiple testing, the strongest associations remained rs4704397 in the PDE8B and rs965513 near FOXE1 (Figure 2). Each copy of the minor A allele for rs4704397 in PDE8B was associated with an increase in TSH levels in both term and preterm infants (Table 2), as well as an increase of 0.6 mIU/L in TSH levels in the combined cohort. For SNP rs965513 in FOXE1 each copy of the minor A allele was associated with a decrease in TSH levels in both term and preterm infants (Table 2), as well as a decrease of 0.2–0.7 mIU/L in TSH levels in the combined cohort. Two other SNPs in FOXE1 (rs1443432 and rs3021523) showed marginal (p<0.05) significance with TSH levels. Each copy of the G allele of rs1443432 and each copy of the C allele of rs3021523 were associated with a decrease in TSH levels in both term and preterm infants (Table 2), as well as a decrease of 0.2–0.5 and 0.2–0.6 mIU/L in TSH levels in the combined cohort respectively. Haplotype analysis revealed significant associations of specific allele combinations with TSH levels. Near the FOXE1 gene, the presence of the AT and GT haplotypes at rs965513 and rs1443433 was significantly associated with either a decrease or increase of TSH levels, respectively (p=4.2×10−4 and p=4.6×10−4) (Table 3).

Table 2.

TSH means and standard deviations for PDE8B and FOXE1 significant SNPs

| SHL term (N=799) | SHL preterm (N=404) | NICU preterm (N=380) | All Cohorts |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | SNP | Mean(SD) | P-value | Mean(SD) | P-value | Mean(SD) | P-value | P-value |

| PDE8B | rs4704397 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.3×10−4 | |||

| AA | 10.2±4.5 | 8.0±4.6 | 6.2±3.9 | |||||

| GA | 8.7±4.6 | 7.5±4.6 | 6.2±3.9 | |||||

| GG | 8.4±4.3 | 6.7±4.3 | 5.3±3.5 | |||||

| FOXE1 | rs965513 | 5.2×10−3 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 6.4×10−4 | |||

| AA | 9.0±5.0 | 6.6±3.9 | 5.1±3.4 | |||||

| GA | 8.5±4.3 | 7.1±4.3 | 5.8±3.7 | |||||

| GG | 9.3±4.6 | 7.7±4.8 | 6.2±3.9 | |||||

| rs1443432 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.02 | ||||

| AA | 9.3±4.5 | 7.6±4.8 | 6.1±3.9 | |||||

| AG | 8.6±4.4 | 7.3±4.5 | 5.9±3.8 | |||||

| GG | 8.8±4.9 | 7.1±3.8 | 5.1±3.2 | |||||

| rs3021523 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.03 | ||||

| CC | 8.5±4.4 | 6.8±3.2 | 5.6±2.5 | |||||

| TC | 8.7±4.4 | 6.9±4.6 | 5.7±3.5 | |||||

| TT | 9.1±4.6 | 7.6±4.6 | 6.1±4.0 | |||||

Table 3.

SNP haplotypes in the FOXE1 gene that are significantly associated (p<0.001) with natural log transformed TSH levels

| SNPs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Haplotype | Frequency | Beta | P-value |

| FOXE1 | rs965513 – rs1443433 | |||

| AT | 0.23 | −0.08 | 4.2×10−4 | |

| GT | 0.62 | 0.07 | 4.6×10−4 |

Frequency: frequency of haplotype indicated. Beta: beta coefficient for linear regression model; positive value indicates the haplotype is associated with an increase in TSH level, negative value indicates the haplotype is associated with a decrease in TSH level. P-value = p-value for association between natural log transformed TSH and a specific haplotype composed of the alleles listed.

The four remaining SNPs were marginally significant with TSH levels; rs9308765 on chromosome 2 (p=0.01), rs657152 in the ABO gene (p=0.02), rs4892386 in the SLC16A2 gene (p=0.01), and rs1527680 in the PPP1R9A gene (p=0.04). However, the association between these SNPs and TSH levels were not always in the same direction in the three studied cohorts, and further investigation is needed to confirm the associations (Supplemental Table S3, online). While there were no significant single locus associations with TSH levels in TSHR in any of the cohorts the presence of the AGT haplotype at rs10149689, rs4903957, and rs11159483, the GTT haplotype at rs4903957, rs11159483, and rs2075179, the AGTT haplotype at rs10149689, rs4903957, rs11159483, and rs2075179, and the GTTA haplotype at rs4903957, rs11159483, rs2075179, and rs12885526 were significantly associated with TSH levels (p=7.9×10−4, p=6.2×10−4, p=4.2×10−5, and p=7.8×10−4 respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

SNP haplotypes in the TSHR gene that are significantly associated (p<0.001) with natural log transformed TSH levels

| SNPs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Haplotype | Frequency | Beta | P-value |

| TSHR | rs10149689-rs4903957-rs11159483 | |||

| AGT | 0.06 | −0.16 | 7.9×10−4 | |

| TSHR | rs4903957-rs11159483-rs2075179 | |||

| GTT | 0.05 | −0.16 | 6.2×10−4 | |

| TSHR | rs10149689-rs4903957-rs11159483-rs2075179 | |||

| AGTT | 0.03 | −0.28 | 4.2×10−5 | |

| TSHR | rs4903957-rs11159483-rs2075179-rs12885526 | |||

| GTTA | 0.05 | −0.17 | 7.8×10−4 |

Frequency: frequency of haplotype indicated. Beta: beta coefficient for linear regression model; positive value indicates the haplotype is associated with an increase in TSH level, negative value indicates the haplotype is associated with a decrease in TSH level. P-value = p-value for association between natural log transformed TSH and a specific haplotype composed of the alleles listed.

Discussion

Elucidating the genetic basis of TSH variability is currently an area of interest to further the understanding of adult conditions related to TSH levels. For example, low serum TSH levels are associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation in adults over 60 years old (11). Thyroid hormone levels within the normal physiological range have also been shown to affect bone mass and density in healthy men aged 25–45 years (12), as well as in men and women above 55 years of age (13). Thyroid hormones also play a key role in neonatal as well as adult normal physiology, affecting almost all tissues and maintaining healthy status of all human systems including cognition, cardiovascular function, skeletal health, and balanced energy and metabolic status (14). This is particularly relevant in preterm infants were the variability of TSH is particularly high because of postnatal changes in thyroid function due to premature interrupted exposure to maternal thyroid hormones as well as an immature HPA (2).Understanding the shared genetic associations with TSH levels in both the neonatal period as well as through adulthood will be useful for earlier prediction of risk to adult diseases that are affected by TSH levels.

In this light, we aimed to identify genetic polymorphisms that may play a role in TSH variation, especially, in preterm infants. We observed genetic associations that have an effect on TSH levels in either or both term and preterm infants. However, most of our nominally significant associations were found in the term population, and these associations reached multiple testing correction levels of significance in all populations combined. This may be due to the wide range of variability in TSH levels of preterm infants due to immature HPA and the skewed nature of our preterm population where early preterm infants are overrepresented. Our most significant association was with SNP rs4704397 in PDE8B gene (p=1.3×10−4). Each copy of the minor A allele was associated with an increase of 0.6 mIU/L in TSH levels in the combined cohort. This finding is consistent with what has previously been reported in adult serum TSH levels (7). The PDE8B gene is expressed most abundantly in the thyroid gland where it has threefold higher levels than in the next highest tissue (15). It is expressed at lower levels in some other tissues including the brain, spinal cord, and placenta (16). The PDE8B gene encodes a high affinity adenosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP)-specific phosphodiesterase to regulate the level of cAMP in cells and plays a vital role in signal transduction (15, 16). Common genetic variants in PDE8B may affect steroid hormone physiology, such as levels of TSH. For example, an intronic SNP in PDE8B (rs4704397) that was identified in the genome-wide association study by Arnaud-Lopez et al. (7) associated with adult serum TSH levels was then reported to be associated with subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy (17), as well as with TSH levels in obese children (18). Interestingly, we found the same SNP to be associated with TSH levels in both preterm and term infants suggesting that this gene plays an important role in regulating TSH levels at birth as well as thyroid function throughout life. All four studies (adult serum TSH level (7), pregnancy TSH level (17), obese children TSH level (18), and this newborn TSH level study) came to the same finding that each copy of the minor A allele was associated with an increase in TSH levels. In the Arnaud-Lopez et al. paper, the authors suggest that since cAMP is necessary for thyroid-hormone secretion due to TSH stimulation; when PDE8B catalyzes the hydrolysis and inactivation of cAMP in the thyroid gland, it results in decreased generation of thyroid-hormone T4 and T3 resulting in the negative feedback loop to act on producing more TSH (7). Hence, genetic variation in PDE8B may affect PDE8B activity resulting in altered cAMP, TSH, and probably other downstream effects. In the Arnaud-Lopez et al. paper, all exons in the PDE8B gene were sequenced in 40 patients to identify a possible etiologic variant in linkage disequilibrium with the intronic rs4704397; however, no coding variants were identified (7). Further investigation and sequencing of this gene will be needed in adult and newborn samples to identify the regulatory regions causing the association between PDE8B and thyroid levels.

We also found SNPs rs965513 and rs1443432 near the FOXE1 gene (p=6.4×10−4 and 0.02 respectively) and SNP rs3021523 in the FOXE1 gene (p=0.03), to be associated with TSH levels in all the populations combined. Although, only rs965513 meets multiple testing correction level of significance while the other two SNPs are only marginally significant, this may be secondary to the moderate, but not complete, linkage disequilibrium (LD) with each other (rs965513, rs1443432: D’=0.863, r-squared =0.519; rs965513, rs3021523: D’=0.835, r-squared=0.48) and where rs965513 and rs1443433 also have strong effects as part of a haplotype associated with TSH levels. FOXE1 gene encodes a transcription factor that is essential for the initiation of thyroid differentiation at the embryonic stage (19). Mutations of the FOXE1 gene may result in thyroid dysgenesis leading to both familial as well as cases of syndromic congenital hypothyroidism in the Bamforth-Lazarus Syndrome, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) #241850 (http://omim.org/), a rare inherited disorder characterized by CH, cleft palate, and spiky hair (20). FOXE1 also plays an important role in regulating the transcription of different thyroid-specific genes resulting in regulation of thyroid-hormone synthesis (21). Both of two SNPs, rs965513 near FOXE1 (20) and rs1443434 in FOXE1 gene (22), have been previously shown to be associated with adult serum TSH levels. Our replication of this finding with newborn TSH levels further implicates involvement of this locus in determining TSH levels in newborns; indicating that this association is present at birth.

We further identified four haplotypes in the TSHR gene to be significantly associated with TSH levels. The protein encoded by the TSHR gene is the TSH receptor (TSHR). TSHR is present on thyroid cells, and when activated by TSH secreted from the pituitary gland, intracellular cAMP is upregulated resulting in activation of various cellular processes ending with an increased production of thyroid hormone (23). SNPs in the TSHR gene were previously found to be associated with adult serum TSH levels in a GWAS reported by Arnaud-Lopez et al. (7). We did not find an association with single SNPs in the TSHR gene; however we found SNP haplotypes to be associated with newborn TSH levels.

One limitation of this study is that we were not able to connect TSH measurements to medical record information to obtain more detailed information on neonatal illness or race for the SHL preterm and term cohorts. However, in 2009 86.9% of the births in Iowa were Caucasian, suggesting that the majority of our samples are from Caucasians. Another limitation was that we do not have follow up data on our study cohort to check for development of conditions later in life. On the other hand, our study illustrates the utility of having IRB reviewed access to stored, de-identified newborn dried bloodspot samples for genetic studies. It is also, to our knowledge, the first study to examine genetics of TSH levels in newborns. Unraveling the genes that affect TSH levels will enhance our understanding of the genetic regulation and physiology of the thyroid and the pituitary-thyroid axis as well as the genes that may be involved in different thyroid diseases. This knowledge may be used to help individualize thyroid related treatments according to the individual’s specific genotype. Recognizing TSH variation and the genetic factors affecting it early in infancy may be a useful adjunct in population screening for the early prediction and possible treatment or prevention of adult diseases and conditions affected by TSH levels.

Methods

Study Population

Study samples were obtained from two sources. The first was from the University of Iowa SHL where we obtained de-identified residual dried blood spots on a population of Iowa neonates; term (n=827) and preterm (n=413). Approval for use of the deidentified data and blood spot cards was granted by the Iowa Department of Public Health and a waiver of consent was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa (IRB# 200908793). All subjects had TSH measurements between day 1 and 3 of life and had not received a transfusion prior to sample collection. Preterm birth was defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation. Gestational age was determined from the records obtained from the SHL. Quantification of TSH was performed at the SHL using CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) certified methods. TSH was determined by solid phase, time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay from dried newborn blood spots using PerkinElmer’s AutoDELFIA platform (Waltham, MA). DNA was extracted from one dried whole blood spot for all term samples and two dried whole blood spots for all preterm samples using the AutoGen (Holliston, MA) QuickGene-810 nucleic acid extraction machine with the DNA Tissue Kit (AutoGen) and following manufacturer’s recommendations.

The second source was from the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics NICU. Preterm infants admitted to this NICU were either born in house or transferred from referring units within the first 28 days of life. Preterm birth was also defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation. Gestational age was determined from the first day of the last menstrual period. Gestational age was confirmed through obstetrical judgment and if uncertain, ultrasound measurements were used for confirmation. All families provided signed informed consent (UI IRB199911068) to be included in a repository of samples designed to provide DNA and limited epidemiologic data to study complications of newborn infants (24). Preterm infants from singleton births, without congenital anomalies, with gestational ages between 22 to 36 weeks (n=402) were included in this study, and early preterm infants (<34 weeks gestation) were overrepresented from their population frequency due to the referral patterns of our NICU. TSH measured by the SHL as part of routine neonatal screening was linked to the sample and medical record data. DNA was extracted from cord blood, discarded venous blood or buccal swab for all infants. All DNA was extracted using standard protocols.

Marker Selection and Genotyping

We chose a total of 45 SNPs encompassing 24 candidate genes and eight intergenic loci. The list of genes and SNPs genotyped are in Table 5. SNPs were chosen either based on their previously reported associations with adult serum TSH levels, or based on thyroid biology and candidate genes from the literature. In the first case, we chose the exact SNPs that were reported to be associated. In the second case, we chose SNPs from the HapMap database (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) based on their ability to tag the surrounding SNPs in the candidate gene. All SNPs were genotyped using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on the EP1 SNP Genotyping System and GT48.48 Dynamic Array Integrated Fluidic Circuits (IFCs) (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA). All SNP genotyping assays were available and ordered using the Assay-on-Demand service from Applied Biosystems. These genotyping assays included primers to amplify the region containing the SNP of interest and two TaqMan Minor Groove Binder probes that are specific to the polymorphic variant alleles at the site labeled with different fluorescent reporter dyes, FAM and VIC. All reactions were performed using standard conditions supplied by Fluidigm. Following thermocycling, fluorescence levels of the FAM and VIC dyes were measured using the EP1 Reader (Fluidigm) and genotypes were scored using the Fluidigm Genotyping Analysis software (Fluidigm). Genotypes were uploaded into a Progeny database (Progeny Software, LLC, South Bend, IN) containing the phenotypic data for subsequent statistical analysis. Genotyping efficiency was >98% for all markers with the exception of rs9322817 in HACE1 (93.5%) and rs1014968 in TSHR (90.8%). Forty-three individuals with genotyping efficiency <95% (i.e. missing data on >2 markers) were excluded from further analysis. Additionally, only 16 individuals had an abnormal (TSH≥25.0 mIU/L) level on initial screen. In order to avoid potential confounding, these individuals were excluded leaving 404 SHL preterm neonates, 799 term neonates and 380 NICU neonates for analysis.

Table 5.

List of genotyped markers

| Marker | Gene | Location | Chromosome | Position | MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10917469 | - | Intergenic | 1 | 19843576 | 0.19 |

| rs1321108 | TSHB | Promoter | 1 | 115572365 | 0.5 |

| rs4849179 | PAX8 | Intron | 2 | 113985170 | 0.42 |

| rs877202 | PAX8 | Intron | 2 | 114019129 | 0.26 |

| rs9308765 | - | Intergenic | 2 | 119043209 | 0.11 |

| rs2288629 | EPHA4 | Intron | 2 | 222307310 | 0.16 |

| rs1505287 | THRB | Intron | 3 | 24412690 | 0.37 |

| rs784490 | TTC21A | Intron | 3 | 39173530 | 0.24 |

| rs1976324 | - | Intergenic | 3 | 87212806 | 0.31 |

| rs10493147 | HSPA4L | Intron | 4 | 128737499 | 0.24 |

| rs2545308 | - | Intergenic | 4 | 181637915 | 0.44 |

| rs27178 | PDE4D | Intron | 5 | 58587025 | 0.46 |

| rs4704397 | PDE8B | Intron | 5 | 76518442 | 0.48 |

| rs9342104 | CGA | Intron | 6 | 87798512 | 0.44 |

| rs6942231 | HACE1 | Intron | 6 | 105191814 | 0.45 |

| rs9322817 | HACE1 | Intron | 6 | 105232233 | 0.4 |

| rs2983521 | PDE10A | Intron | 6 | 166057203 | 0.2 |

| rs10486365 | TMEM196 | Intron | 7 | 19801364 | 0.1 |

| rs6977660 | TMEM196 | Intron | 7 | 19805480 | 0.14 |

| rs10499559 | - | Intergenic | 7 | 22109459 | 0.16 |

| rs10486653 | NPSR1 | Intron | 7 | 34711663 | 0.2 |

| rs1527680 | PPP1R9A | Promoter | 7 | 94534886 | 0.15 |

| rs2252696 | SLA | Intron | 8 | 134063532 | 0.43 |

| rs7865184 | ZDHHC21 | Intron | 9 | 14687867 | 0.45 |

| rs10512065 | GNAQ | Intron | 9 | 80625644 | 0.13 |

| rs965513 | - | Intergenic | 9 | 100556109 | 0.37 |

| rs1443433 | - | Intergenic | 9 | 100579219 | 0.19 |

| rs1443432 | - | Intergenic | 9 | 100583195 | 0.47 |

| rs894673 | FOXE1 | Promoter | 9 | 100612270 | 0.47 |

| rs3021523 | FOXE1 | Coding exon-synon | 9 | 100616583 | 0.29 |

| rs4460498 | FOXE1 | Downstream | 9 | 100620412 | 0.46 |

| rs4128956 | MED27 | Intron | 9 | 134818509 | 0.38 |

| rs657152 | ABO | Intron | 9 | 136139265 | 0.38 |

| rs944289 | - | Intergenic | 14 | 36649246 | 0.41 |

| rs10149689 | TSHR | Promoter | 14 | 81415800 | 0.46 |

| rs4903957 | TSHR | Intron | 14 | 81448511 | 0.32 |

| rs11159483 | TSHR | Intron | 14 | 81501311 | 0.25 |

| rs2075179 | TSHR | Coding exon-synon | 14 | 81562998 | 0.1 |

| rs12885526 | TSHR | Intron | 14 | 81574429 | 0.36 |

| rs1991517 | TSHR | Coding exon-missense | 14 | 81610583 | 0.1 |

| rs945006 | DIO3 | 3'UTR | 14 | 102029277 | 0.12 |

| rs3908399 | - | Intergenic | 20 | 12901275 | 0.27 |

| rs6030171 | PTPRT | Intron | 20 | 40994094 | 0.31 |

| rs500243 | SLC16A2 | Intron | X | 73676685 | 0.37 |

| rs4892386 | SLC16A2 | Intron | X | 73718735 | 0.32 |

MAF, minor allele frequency.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared between cohorts using Chi-square tests for categorical traits and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous traits. All demographic factors listed in Table 1, year of sampling and TSH assay lot were individually associated (P≤0.001) with the natural log transformed TSH measurement in the combined (N=1,583) sample cohort using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Step-wise modeling was used to determine a final list of covariates for inclusion when testing association between SNP genotype and TSH level. Gestational age (P=5.55×10−19), age at time of sampling (P=1.63×10−42), gender (P=1.52×10−8) and year of sampling (P=7.36×10−4) were all significantly associated with TSH in the final model; birth weight (P=0.02), assay lot (P=0.09) and TPN (P=0.25) were not included in the final model due to marginal significance. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was evaluated for each marker using Fisher exact tests for all cohorts. All markers were tested for association with the natural log transformed TSH measurement adjusting for gender, gestational age, age at time of sampling and year of sampling using ANOVA in the combined cohort (N=1,583). A Bonferonni significance threshold of P=0.001 (0.05/45 markers) was used to correct for multiple testing. Sub-analyses were performed in each cohort separately to determine individual population effects. All analyses were performed in STATA software version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Haplotype Analysis

Haplotype analysis of SNPs in the same gene or region was used to evaluate regional associations with natural log transformed TSH levels. Haplotype analysis was performed with linear regression adjusted for gender, gestational age, age at time of sampling and year of sampling in the combined cohort. Haplotype analysis was performed using sliding windows of 2, 3, and 4 SNPs along a gene or region of interest. Haplotype analyses were performed in PLINK software (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/) (25).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to Kim Piper at the Iowa Department of Public Health and the members of the Congenital and Inherited Disorders Advisory Committee for their enthusiastic support and management of this project. We thank Teresa Snell, Franklin Delin, and Dariush Shirazi from the State Hygienic Laboratory for their assistance in the acquisition of the newborn screening data and samples. We would like to thank the families that participated in this study; our research nurse Laura Knosp for enrolling families and collecting specimens. We would like to thank Susan Berends, Tamara Busch, Daniel Cook, Osayame Ekhaguere, and Lauren Fleener at the University of Iowa for their technical assistance with sample management, DNA extraction, and genotyping. We thank Sara Copeland at the Health Resources Services Administration for her guidance on this project.

STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT: March of Dimes (grants 1-FY05-126 and 6-FY08-260) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) (grants R01 HD-52953, R01 HD-57192, and K99 HD-65786). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kumar J, Gordillo R, Kaskel FJ, Druschel CM, Woroniecki RP. Increased prevalence of renal and urinary tract anomalies in children with congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 2009;154:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinton CF, Harris KB, Borgfeld L, et al. Trends in incidence rates of congenital hypothyroidism related to select demographic factors: data from the United States, California, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S37–S47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1975D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilcken B, Wiley V. Newborn screening. Pathology. 2008;40:104–115. doi: 10.1080/00313020701813743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaFranchi S. Thyroid function in the preterm infant. Thyroid. 1999;9:71–78. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panicker V, Wilson SG, Walsh JP, et al. A locus on chromosome 1p36 is associated with thyrotropin and thyroid function as identified by genome-wide association study. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panicker V, Wilson SG, Spector TD, et al. Heritability of serum TSH, free T4 and free T3 concentrations: a study of a large UK twin cohort. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnaud-Lopez L, Usala G, Ceresini G, et al. Phosphodiesterase 8B gene variants are associated with serum TSH levels and thyroid function. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1270–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang SJ, Yang Q, Meigs JB, Pearce EN, Fox CS. A genome-wide association for kidney function and endocrine-related traits in the NHLBI's Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rawal R, Teumer A, Volzke H, et al. Meta-analysis of two genome-wide association studies identifies four genetic loci associated with thyroid function. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3275–3282. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen PS, van der Deure WM, Peeters RP, et al. The impact of a TSH receptor gene polymorphism on thyroid-related phenotypes in a healthy Danish twin population. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:827–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, et al. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1249–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roef G, Lapauw B, Goemaere S, et al. Thyroid hormone status within the physiological range affects bone mass and density in healthy men at the age of peak bone mass. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:1027–1034. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Deure WM, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, et al. Effects of serum TSH and FT4 levels and the TSHR-Asp727Glu polymorphism on bone: the Rotterdam Study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:175–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panicker V. Genetics of thyroid function and disease. Clin Biochem Rev. 2011;32:165–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakics V, Karran EH, Boess FG. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi M, Matsushima K, Ohashi H, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of human PDE8B, a novel thyroid-specific isozyme of 3',5'-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:751–756. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shields BM, Freathy RM, Knight BA, et al. Phosphodiesterase 8B gene polymorphism is associated with subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4608–4612. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grandone A, Perrone L, Cirillo G, et al. Impact of phosphodiesterase 8B gene rs4704397 variation on thyroid homeostasis in childhood obesity. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:255–260. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parlato R, Rosica A, Rodriguez-Mallon A, et al. An integrated regulatory network controlling survival and migration in thyroid organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;276:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castanet M, Polak M. Spectrum of human Foxe1/TTF2 mutations. Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;73:423–429. doi: 10.1159/000281438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Common variants on 9q22.33 and 14q13.3 predispose to thyroid cancer in European populations. Nat Genet. 2009;41:460–464. doi: 10.1038/ng.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medici M, van der Deure WM, Verbiest M, et al. A large-scale association analysis of 68 thyroid hormone pathway genes with serum TSH and FT4 levels. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:781–788. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stathatos N. Thyroid physiology. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steffen KM, Cooper ME, Shi M, et al. Maternal and fetal variation in genes of cholesterol metabolism is associated with preterm delivery. J Perinatol. 2007;27:672–680. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.