Abstract

Investigations of racial bias have emphasized stereotypes and other beliefs as central explanatory mechanisms and as legitimating discrimination. In recent theory and research, emotional prejudices have emerged as another, more direct predictor of discrimination. A new comprehensive meta-analysis of 57 racial attitude-discrimination studies finds a moderate relationship between overall attitudes and discrimination. Emotional prejudices are twices as closely related to racial discrimination as stereotypes and beliefs are. Moreover, emotional prejudices are closely related to both observed and self-reported discrimination, whereas stereotypes and beliefs are related only to self-reported discrimination. Implications for justifying discrimination are discussed.

Keywords: Prejudice, Discrimination, Race, Attitude, Affect, Emotion

Introduction

What people actually do in relation to groups they dislike is not always related to what they think and feel about them. (Allport, 1954, p. 14)

From LaPiere’s (1934) classic demonstration onward, social psychologists have puzzled about how to predict discrimination from people’s self-reported reactions to outgroups (i.e., those to which they do not belong). Allport’s book was the first to detail cognitive, attitudinal, and emotional prejudices, but proved agnostic as to which mattered more in predicting discrimination. Over 50 years later, social psychology now knows more both about behavioral responses to outgroups and about their best predictors. Inequality may be maintained by emotional reactions more than by cognitive beliefs.

Until recently, social psychological research tended to focus on stereotyping (beliefs about outgroup traits), other cognitions (e.g., beliefs about relevant policies), and overall evaluation (unspecified positive-versus-negative evaluation), over the study of emotional prejudices (differentiated emotions toward outgroups) and discrimination (biased behavior toward an outgroup, whether more negative or less positive) (Fiske, 1998). Although stereotypes and beliefs have been studied extensively, the extent to which they predict discrimination remains in question.

Recently, however, emotional prejudice has returned as usefully predicting discrimination (e.g., Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2007; Esses & Dovidio, 2002). However, these previous findings provide tantalizing promissory notes because they are isolated studies. The current meta-analysis investigates—across many studies—whether and under what circumstances racial emotional prejudices relate to racial discrimination, compared to how racial beliefs and stereotypes do so. To address these questions, we quantitatively survey past studies measuring racial attitudes (including beliefs, stereotypes, emotional prejudices, overall evaluations) and racial discrimination.1

Relationships among emotions, stereotyping, and discrimination remain ambiguous. We hypothesize that emotional prejudices more directly predict discrimination than stereotypes and beliefs do. Literatures on emotions, automaticity, attitudes, and prejudice all implicate emotions as a primary cause of behavior in general, but discrimination in particular.

Emotions as Predictors of Discrimination

If we want to predict discrimination, why should emotional prejudices be especially useful? Emotional prejudices already prove superior predictors separately of evaluations and behavioral intentions, which are closely linked to actual behavior.

First, theory and research in various areas closely and directly link emotions to evaluations. Zajonc (1980) asserted that emotions precipitate evaluations, bypassing cognition altogether. Mood (non-specific emotion) influences both judgment (e.g., Schwarz & Clore, 1988) and stereotyping (e.g., Park & Banaji, 2000). Differentiated emotions toward political candidates predict overall evaluations better than trait descriptions do (Abelson, Kinder, Peters, & Fiske, 1982). If people automatically evaluate every newly encountered object (Duckworth, Bargh, Garcia, & Chaiken, 2002), emotion-driven evaluations may color their interaction with it.

Turning to outgroups, both cognitive beliefs and emotional prejudices predict evaluations of various outgroups, with their relative impact varying by target group and perhaps individual differences (Eagly, Mladinic, & Otto, 1994; Esses & Beaufoy, 1994; Haddock, Zanna, & Esses, 1993, 1994; Jackson et al., 1996; Maio, Esses, & Bell, 1994). As one example, emotional prejudices predict overall evaluation of gay men more than stereotypes do (Bodenhausen & Moreno, 2000; Haddock et al., 1993). Most specifically relevant to racial/ethnic outgroups per se, emotional prejudices best predict their overall evaluation (Dijker, 1987; Haddock et al., 1994; Jackson et al., 1996; Stangor, Sullivan, & Ford, 1991). If emotion is so crucial to evaluation of outgroup members, and racial minority groups in particular, it is likely to matter in behavior as well.

But we need to move beyond evaluation to actual behavior. Tomkins (1962) first theorized that emotions were the “motor” for behavior (Zajonc, 1998). Later emotion theorists consider emotion and behavior as two parts of a single unit, “emotion-action tendencies” (Frijda, 1986), or two sides of a “discrete emotion” coin (Izard & Ackerman, 2000; Panksepp, 2000). They theorize that these units are linked for a reason; perhaps emotions evolved in order to direct behavior before cognitions came along (Mandler, 1992). And indeed, fear centers in the brain can cause behavior even while the cognitive centers are still working on full object identification, at least in rats (LeDoux, 1996).

More specific to people, a series of dual-process models in social psychology all converge on automatic initial reactions that may or may not be tempered by controlled overrides, depending on information and motivation to engage in more detailed processing (see Chaiken & Trope, 1999, for a collection). For example, in Fiske and Neuberg’s (1990) continuum model (see also Fiske, Lin, & Neuberg, 1999), the initial perceptual categorization immediately imports affective tags, stereotypic associations, and behavioral tendencies. If it is true that the affect is processed faster than the relevant cognitive associations, as several of the more general emotions theories argue, then behavior might well be driven more closely by such emotional reactions because of their priority. Affect would thus be particularly likely to matter in the most immediate, direct in-person encounters. Moreover, affect has implications for basic approach–avoidance reactions (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1999). In contrast, stereotypes and beliefs are more abstract and less clearly implicate immediate behavioral reactions.

Moving from theory to data: In the previously mentioned voting study, emotions not only predicted evaluations, as noted, but also predicted behavior (ranked vote choice) better than the traits did (Abelson et al., 1982). In both a correlational and an experimental study of prejudice toward gay men, emotional prejudices predict discrimination more than stereotypes or beliefs do [Talaska, Fiske, & Chaiken (2003). Emotional prejudices, stereotypes, and attitudes in the prediction of discrimination. Unpublished manuscript, Princeton University]. In another experiment, focusing on emotions during a pro-Black video impacts discrimination more than focusing on thoughts does (Esses & Dovidio, 2002). All this work suggests that, at least in the case of minority groups, emotional prejudices may especially relate to behavior. Such results create a “wake-up call … to get serious about predicting behavior” (Fiske, 2000). Here, we hypothesize that emotional prejudices will strongly predict discrimination, and do so better than stereotypes and beliefs.

What do we predict for stereotypes and beliefs? Previous research suggests that stereotypes are related to discriminatory behavior, just not as closely as emotional prejudices, at least for many racial/ethnic outgroups. Stereotypes and emotions both highly predict discriminatory intentions, however (Cuddy et al., 2007, 2008; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Mackie, Devos, & Smith, 2000). At least one study indicates that emotions mediate the relationship between stereotypes and behavioral tendencies (Cuddy et al., 2007). For discriminatory intentions, the stereotype–behavior relationship is substantial in one meta-analysis (Schütz & Six, 1996). Nevertheless, behavioral intentions (sometimes called behavioroid measures) do not correspond perfectly with behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975); other direct motivators are needed.2 We nominate emotional prejudices for that motivator.

We hypothesize that stereotypes may direct discrimination, while emotions energize it. Stereotypes and beliefs could powerfully guide people’s behavioral intentions toward an outgroup, but when it comes to actually interacting with an outgroup member, emotions decide whether a behavior is performed. We hypothesize that emotional prejudices will best predict direct, immediate forms of discrimination, while beliefs will best predict more hypothetical, abstract forms of discrimination.

Previous Efforts to Assess Predictors of Discrimination

The bulk of social psychology’s small body of research on discrimination simply documents the existence of discrimination (for an early review, see Crosby, Bromley, & Saxe, 1980). The traditional meta-analytic question for predictors of discrimination would assess the relationship between attitudes toward outgroups and discrimination. Indeed, a meta-analysis has recently focused on this question: A moderate relationship does link overall attitudes and discrimination against outgroups (Schütz & Six, 1996). This question is of less primary importance to this particular analysis.

Of more concern are our theoretical questions focused on different kinds of predictors and different kinds of outcomes. The strongest predictors of discrimination constituted various kinds of “support for racial segregation” (Schütz & Six, 1996), but this analysis did not attempt to break down the predictors any further, our main purpose here. Moreover, all biased attitudes predicted discriminatory intention better than actual discriminatory behavior, and even less well predicted behavior that involved direct contact with the target.

Most recently, Dovidio, Esses, Beach, and Gaertner (2002) conducted a meta-analytic review that did compare emotional prejudices and more cognitive interracial attitudes as correlates of discrimination in inter-racial contact. The more dramatic relationship emerged when affective, rather than cognitive, attitudes were measured, but the number of studies was small, only nine. The current review conducted a more exhaustive search. In addition to inter-racial contact as a behavioral outcome variable, the earlier review also analyzed the relation of affective versus cognitive attitudes to measures of policy support (finding 22 studies). However, we classify policy support as a cognitive measure of attitude, rather than a measure of behavior.

Goals of the Current Analysis

This meta-analysis represents the convergence of previous racial attitude–behavior meta-analyses: It exhaustively reviews the racial prejudice-discrimination literature through 2002, with attention first to the relative amount of cognition and emotion in the attitude measure. Second, the current meta-analysis newly categorizes different measures of discrimination, guided by our theoretical focus on direct measures of behavior, compared with hypothetical or intended behaviors. Third, this review separates actual intergroup emotions from evaluative attitudes. We next elaborate on each of these points.

Studies relating racial attitudes to discrimination constitute a heterogeneous field. Researchers have tried to predict a host of different discrimination measures using a host of different attitude measures. The current analysis attempts to impose some order on this past work by categorizing the attitude, the behavior, and the interaction of the two measures by distinctions we believe may be meaningful. First and foremost, as noted, this meta-analysis focuses on the relative cognitive or affective content of attitude measures, and on specific emotions (anger, contempt, pity, fear, envy), separate from evaluative measures (e.g., warm-cold).

Secondly, we focus on the closeness with which the behavior measure taps actual behavior. We believe that in the case of inter-racial relations, behavioral intentions will mask the attitude–behavior relations. People’s discriminatory behavior is so carefully monitored in our multi-cultural society that intentions may be farther from actions than in other attitude domains (e.g., Devine, Monteith, Zuwerink, & Elliot, 1991; Monteith, 1996a, b).3

Overall, we believe that not all inter-racial attitudes are alike, in concert with the “new look” in attitude research (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Distinction in structure and character of the racial attitude will matter. One of the core distinctions is whether, in measuring an attitude, the researchers measured a more emotional or more cognitive component. Hence we assess and compare the relationships between discrimination and, respectively, beliefs, stereotypes, emotional prejudices, behavioral intentions, and overall valence (see Table 1 for our attitude coding criteria). The current meta-analysis sought to answer whether emotional prejudices toward racial outgroups have been more predictive of behavior than cognitive concepts are, and whether more so for actual behavior than intended or hypothetical behavior.

Table 1.

Coding criteria for attitude focus

| Attitude focus | Coding criteria | Scale item example |

|---|---|---|

| Emotion | Must measure emotions/feelings toward outgroups. Must go beyond overall positive/negative valence | “Have you ever felt admiration for Surinam people?”(Dijker, 1987, p. 311) |

| Stereotype | Must measure endorsement of outgroup holding various traits. Traits cannot be limited to terms that connote nothing more than overall valence (e.g., beautiful, ugly, good vs. bad) | “For each listed trait [of 41] (foresight, suggestibility, self-control, intelligence, etc.) the subject was asked whether he considered, first Negroes, then mulattoes, as inferior, equal or superior to Whites (Bastide & Van Den Berghe, 1957, p. 690)” |

| Belief | Any belief that does not concern outgroup traits. Cannot include beliefs about future behaviors. Can include beliefs about the reasons behind outgroups’ status, policies, and what should be done about outgroups | Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) |

| Stereotype and belief | Any combination of above two categories | |

| Overall valence | Must measure overall positive versus negative evaluation, without reference to specific beliefs, stereotypes, emotions, or behaviors | Rating of own prejudice level from “very unprejudiced” to “very prejudiced” (Harkins & Becker, 1979, p. 202) |

| Valence and emotion | Any combination of overall valence and emotion. Includes feelings limited to simple positive-negative connotations (e.g., feeling unfavorable vs. favorable), such as in feeling thermometers | “Use the feeling thermometer to give your general impression of Surinam people. You may use any number between 0 and 100°. Numbers between 50 and 100 mean that you feel favourable towards these people. Numbers between 0 and 49 mean you feel unfavourable towards Surinam people” (Dijker, 1987, p. 312) |

| Valence and stereotype | Any combination of overall valence and stereotype. Includes traits limited to simple positive-negative connotations (e.g., good vs. bad, kind vs. unkind) measured implicitly | Word-completion, 12 words paired with Black, 12 with White faces; words could be completed as positive, negative, and/or neutral. (Dovidio, Kawakami, Johnson, Johnson, & Howard, 1997) |

| Behavioral intention | Must ask participants how they think they would behave toward an outgroup member | “I wouldn’t mind attending a party in which there were both Negro and White couples” (Linn, 1965, p. 356) |

| Mixed/other | Any other combination, unspecified, or other type of focus (e.g., motivation behind prejudice; Plant & Devine, 1998) | Multifactor Racial Attitudes Inventory (Woodmansee & Cook, 1967) |

Method

Sample of Studies

Our analysis initially intended to encompass biased attitudes and behavior toward all outgroups. However, in searching the literature, almost all studies dealt with racial/ethnic relations. Most other outgroups were not addressed in more than one study each, so we decided to limit our analyses to racial/ethnic outgroups. Attitudes of minority group members toward majority groups were not included because these attitudes were not often studied and might have different measurement characteristics than attitudes toward racial minority groups. Hence the studies assessed attitudes of the majority toward minorities.

Inclusion Criteria

We then selected from these studies based on more specific inclusion criteria. Each study had to include a measure of attitude and behavior toward a racial/ethnic minority group. We defined “attitude” as any measurement of thoughts, feelings, or overall attitudes toward a group, a group member, or issues relating to the group, such as government policies. To separate biased behaviors from biased thoughts or feelings, the current analysis defined behavior as a biased action that, from the viewpoint of each participant, had consequences either for the participant or for the target of the measure. This included measures of current and past overt and non-verbal behaviors, commitments to later behaviors (such as signing a form agreeing to have one’s picture taken later), and judgments that had implications for the target (such as a hiring decision that participants thought had real influence).

We selected studies published in English language, peer-reviewed journals during or before 2002. Studies were found through a variety of methods. First, we gathered studies used in previous general attitude–behavior meta-analyses (Kraus, 1995; Wallace, 1994), prejudice-discrimination meta-analyses (Dovidio et al., 2002; Schütz & Six, 1996), and a review of discrimination studies (Crosby et al., 1980). We then conducted searches on the PsychInfo database using keywords such as: “attitud* and discriminat* and ethnic*”, “prejudic* and affect* and discriminat*”, “ behavior and prejudic*”, “emotion* and outgroup”, “emot* and attitude* and rac* in descriptors or subject”, “prejudice and discrimination in title,” and “(confederate in abstract) and (black and white in abstract) and (social in source).” We also searched the references of studies gathered for other relevant studies.

Some studies included more than one measure of attitude or behavior. We coded effect sizes for every attitude–behavior pair in each study. Although this leads to issues of non-independence in calculating the overall effect size, we were more interested in the effects of moderating variables. Also, because so few studies used emotion measures—our primary interest—selecting one effect size from each study would limit our analyses even further.

Studies Omitted

Of the studies retrieved, many were then omitted according to our aforementioned definitions of attitude and behavior. We did not include studies if the attitude was assumed, rather than measured (e.g., known-groups studies, such as people from different regions, if no attitude measure was used, e.g., Branthwaite & Jones, 1975). A few studies were also omitted because their methods could have biased the relationship between attitude and behavior. Studies that gave false consensus information regarding participants’ attitudes (e.g., Sechrist & Stangor, 2001; Tarter, 1969) were omitted, as were studies that gave false feedback on participants’ attitudes themselves (e.g., Dutton, 1973). Our definition of behavior omitted behavioral intentions without consequences for the participant, such as Bogardus’s (1933) social distance scale, which poses hypothetical situations toward abstract rather than specific individuals (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Also, two studies that included a valid attitude and behavior measure did not report the association between these measures, so they were omitted. We also did not include studies that pre-selected only highly prejudiced or only non-prejudiced participants, due to range restriction concerns. This left 57 studies reported in 54 papers.

Variables Coded from Each Study

Information was coded relating to the study in general and variables specific to the attitude measure, the behavior measure, and the effect size. If the attitude or behavior measure was not fully described in the study, the cited source of the measure(s) was retrieved for coding.

Attitude Measure

We coded how cognitively and affectively focused the measure was (for each dimension: not at all, a bit, somewhat, very, completely and explicitly). For our primary measures of interest, we coded the focus of the attitude measure [emotion, stereotype (cognition about a personal characteristic), belief (cognition not about a personal characteristic), behavioral intention, mixed/other].

To characterize the attitude measure itself, we coded its target (outgroup member, outgroup, policy toward outgroup, policy affecting outgroup, other), target concreteness [concrete (real person or relevant policy), somewhat concrete (a fictional person or policy loosely realized), abstract], type of measure (Likert scale, feeling thermometer, semantic differential, yes/no, Thurstone scale, lexical decision, IAT), whether the measure was implicit or explicit, the valence of the attitude measured (positive, negative, both), the measurement method (continuous, median split, extreme groups, one question split, Thurstone), the number of attitude items, and the reliability of the measure.

To characterize the setting of the attitude measurement, we coded where it took place [laboratory, mass testing, telephone, interview survey (door-to-door), mail survey, field, other], and whether measurement was public (completely public, public within study, supposedly private but done in the presence of others, private except for experimenter, completely private). On a randomly selected subset of 15 distinct measures used, reliability for this five-level variable was fine, Cohen’s kappa = .90.

Behavior Measure

Social psychologists often measure discrimination to understand interpersonal in-person discrimination. We believe that past racial attitude-discrimination studies have mimicked actual behavior with varying degrees of success. Hence, we coded discrimination measures for aspects that more or less closely approximate an in-person interaction with an outgroup member. We call the ability of a measure to approximate face-to-face interaction behavior measurement directness. We attempted to choose behavior measurement directness characteristics that could be coded relatively objectively. Also, as noted, we believe the more direct the behavior measured, the more closely emotional prejudices will be related to them, and the less closely stereotypes and beliefs will.

The directness of a behavior has proved an important distinction in the aggression literature (Buss, 1961). Conceptually, one way to sort these behaviors is by whether or not an outgroup member is present at the time of behavior measurement. The presence of an outgroup member might cue distinct processes, for example, more emotional ones, so the correlates of behavior might differ with and without outgroup members present. The more concrete the behavior target, the more it should resemble an actual interpersonal situation. Whether the measured behavior is directed toward an actual outgroup member may also affect the related attitudes. Coding criteria for all behavior measurement directness characteristics appear in Tables 2 and 3. These characteristics include aspects of the measurement situation (Table 2) and aspects of the behavior measured within that setting (Table 3). The different classes for each characteristic (or variable) appear in descending order of directness. Thus, moving down through classes of a characteristic, the behavior measurement approximates an in-person interaction less and less closely.

Table 2.

Coding criteria for setting of behavior measure, from greater to lesser directness, with regression codes

| Behavior setting characteristic | Class | Coding criteria | Regression code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outgroup presence | Yes | Outgroup member present during measurement, can be experimenter, confederate, fellow participant, or target | 3 |

| Maybe | Outgroup member in (or said to be in) next room during measurement | 2 | |

| No | No outgroup member present during measurement | 1 | |

| Time | Present | Behavior measured during study | 3 |

| Present and future | Behavior measured during study, but includes commitments to later behavior, if ramifications | 2 | |

| Past | Participants asked about past voluntary behavior toward outgroup | 1 | |

| Future | Commitment to later behavior, with ramifications | 0 | |

| Abstraction | Concrete | An actual person or real, fully described policy given during measurement | 4 |

| Fairly concrete | A fictional person or policy, many details given | 3 | |

| Somewhat concrete | A fictional person or policy loosely realized, few details given | 2 | |

| Abstract | Behavior target is outgroup in general | 1 |

Table 3.

Coding criteria for behavior measure, from greater to lesser directness, with regression codes

| Behavior variable | Class | Coding criteria/example | Regression code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact | Yes | Endorsement of measure definitely increases proximity to outgroup member(s) | 3 |

| Maybe | Endorsement of measure might increase proximity to outgroup member(s) | 2 | |

| No | Endorsement of measure does not increase proximity to outgroup member(s) | 1 | |

| Action vs. evaluation | Action | Behavior measured is action toward an outgroup member | 1 |

| Evaluation | Behavior measured is evaluation of outgroup member | −1 | |

| Activeness | Active | Behavior measured involves physical movement | 3 |

| Commitment | Signed commitment to participation in action involving outgroup | 2 | |

| Non-active | Behavior measured only involves writing | 1 | |

| Contingency | Yes | Measured behavior directly affects outgroup member(s) | 3 |

| Yes, in next room | Behavior performed directly affects outgroup member(s) in next room | 2 | |

| No | Behavior does not directly affect outgroup member(s) | 1 |

To characterize the behavior measure further, we coded (a) its target (outgroup member, outgroup, policy toward outgroup, policy affecting outgroup, other), (b) target concreteness [concrete (real person or relevant policy), somewhat concrete (a fictional person or policy loosely realized), abstract], (c) overtness of behavior (verbal, nonverbal, both), (d) directness of behavior (face-to-face, indirect), (e) valence of behavior (positive, negative, both), (f) number of behavior items, (g) the reliability or interjudge correlation of the measure, (h) the time of the behavior (past, during study, commitment to later behavior with ramifications), (i) whether contact with an outgroup member was implied by the behavior (yes, direct but in the next room, no), (j) whether an outgroup member was present during the behavior measurement (yes, in the next room, no), (k) the method of behavior judgment [other person (experimenter, trained judges, confederate, peer observer), objective measure (e.g., shock intensity chosen), objective measure from self-report (e.g., number of blacks hired), self-report], and (l) whether the measure was an overt behavior or a paper-and-pencil measure of behavior.

To characterize the setting of the behavior measure, we coded its location [laboratory, telephone, interview survey (door-to-door), mail survey, field, other], whether measurement was public (completely public, public within study, supposedly private but done in the presence of others, private except for experimenter, completely private), whether an outgroup member was present during measurement (present, in the next room, not present), and targets presented (outgroup only, outgroup and ingroup, multiple outgroups only, other).

Kinds of Validity

Next we come to the question of what type of validity we would like from a racial outgroup behavior measure. Measures targeting only outgroups do tell us about the predictive validity of the measures. However, effect sizes that compare outgroup-directed behavior to ingroup-directed behavior more closely address discriminant validity of the measures. So, both of the conceptualizations are valid; the usefulness of each depends on the desired definition of bias as absolute or comparative.

Another issue, given the mix of designs in the literature, was that many studies, rather than simply measuring an attitude–behavior relationship, also manipulated possible moderators of the attitude–behavior relationship. We dealt with this problem by, when possible, coding three effect sizes for each study that manipulated a variable: the effect size in the experimental condition, in the control condition, and across conditions. Unfortunately, the “control” condition was not always a true control, and it was difficult to detect a naturalistic baseline.

Effect-size Variables

We also coded aspects of each particular attitude–behavior pair: number of studies (k) for the effect size; whether any variable was manipulated during the experiment, and if so, the variable manipulated; the amount of time between the attitude and behavior measure, and the order in which they were measured.

General

To help clarify our analysis, we also analyzed the effects of several variables found important in previous meta-analyses. General variables included year of publication, discipline of journal (social psychology, sociology, business psychology, general psychology), country of study, participant recruitment method (paid, volunteer, course credit, solicited unpaid—e.g., door-to-door survey), male/female ratio, and the participant population (undergraduates, graduate students, adults, children).

Computation and Analysis of Effect Sizes

Previous Study Designs

Another concern, besides different methods in measuring attitudes and discrimination, was differences in the statistical relationship measured and reported in each study. Three different ways of conceptualizing biased behavior toward an outgroup appeared in the literature: (a) as a difference between a participant’s own behavior toward the outgroup and that of the participant’s ingroup peers toward the same outgroup, (b) as a difference between a participant’s behavior toward outgroup members and the participant’s behavior toward ingroup members, or (c) focusing on the discriminant validity of the attitude measure, as a difference in highly prejudiced participants’ behavior toward ingroup and outgroup members without a corresponding difference in behavior found in low-prejudiced participants. The first way conceptualizes bias as a participant behaving more negatively toward an outgroup member than other members of the participant’s ingroup do. These studies measured behavior toward outgroup members only, and reported the relationship of the attitude measure to where a person fell on the continuum of behavior toward outgroup members.

The second type conceptualized bias as an individual behaving more negatively toward outgroup members than toward ingroup members. These studies measured each participant’s behavior toward outgroup and toward ingroup members, then related the attitude measure to the amount of difference between behaviors, within each participant. This conceptualization was also operationalized by allowing behavior toward ingroup and outgroup members, then relating the percentage of behavior directed at the outgroup to the attitude measure.

The third type conceptualized bias as an individual behaving more negatively toward outgroup members than other ingroup members tend to behave toward ingroup members. This type of study used a between-subjects design, measuring each participant’s behavior toward either an outgroup or an ingroup member. These studies then looked at the effect of the interaction of attitude and race of target on behavior, such that attitude affected behavior in the outgroup condition, but not in the ingroup condition.4

Computation of Effect Sizes

Pearson’s r was used as the effect size in the current meta-analysis, as it is the effect size most commonly used for associations between variables (DeCoster, 2001). Effects reported as an r, Kendall’s tau (estimates of r for non-normal data), or R (for multiple scale items) were taken directly from the reported effect. Methods for calculating other effect size estimates were those advised by experts (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). We used Wilson’s (2001) Effect Size Determination Program to calculate most effect size estimates (those from t-tests, one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations, and 2 × 2 cell counts). For effects given as 2 × 2 cell counts, a probit transformation was applied to correct for the artificial dichotomization of the variables. If frequency tables were given for an interaction effect (high versus low prejudice by ingroup members and outgroup members; the third type above), we used the counts for high versus low prejudice participants behaving only toward outgroup members to compute an effect relating prejudice to differences in outgroup-directed behavior, without reference to ingroup-directed behavior. For cell counts larger than 2 × 2, r was computed from the frequency data. If the raw data were available, the effect was computed by analyzing these data.

Effect Size Selection

A few interaction-effect studies that could not be converted to effects relating attitude to outgroup-only behavior were omitted from analyses (Clark & Brock, 1992; Dovidio & Gaertner, 1981; Genthner & Taylor, 1973; Leonard & Taylor, 1981, Study 1; Schwarzwald & Yinon, 1978; Stewart & Perlow, 2001). For studies that manipulated conditions between subjects, we included effect sizes for each condition, if available. If condition was manipulated within subjects, the results across conditions were used. This left 136 effect sizes.

Results

Study Characteristics

Frequencies for all categories of study characteristics for the 57 studies coded (including the six interaction-effect studies for which an r could not be computed) are shown in Table 4. The distribution of the publication year of the 57 studies appeared to be bimodal, reaching its first peak in 1975, and as of 2002 heading toward another peak.

Table 4.

Summary of study characteristics

| Study variable | Class | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Median publication year | 1975.5 | |

| Mean male-to-female ratio | .58 | |

| k | ||

| Gender proportions | All males | 14 |

| More males than females | 11 | |

| Equal males and females | 2 | |

| More females than males | 7 | |

| All females | 8 | |

| Gender not specified | 16 | |

| Journal discipline | Social psychology | 35 |

| Sociology | 12 | |

| Business psychology | 3 | |

| General psychology | 6 | |

| Study location | United States | 49 |

| Canada | 1 | |

| Europe | 5 | |

| Israel | 2 | |

| Brazil | 1 | |

| Population studied | Students | 46 |

| Adults | 8 | |

| Children | 4 | |

| Participant recruitment | Paid | 7 |

| Course credit | 17 | |

| Extra course credit | 2 | |

| Solicited unpaid (e.g., in door-to-door survey) | 13 | |

| Volunteer | 3 | |

| Other/unspecified | 15 | |

Note: k = number of studies

Measurement Characteristics

Attitudes

A total of 101 attitude measurements were coded, again including those from the six interaction-effect studies for which an r could not be computed. Table 5 shows frequencies for all characteristics.

Table 5.

Summary of attitude measure characteristics

| Variable | Class | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Median number of attitude items | 8 | |

| k | ||

| Setting | Laboratory | 17 |

| Mass testing | 18 | |

| Classroom | 19 | |

| Interview (face-to-face, door-to-door) survey | 8 | |

| Mail survey | 12 | |

| Interview or mail survey | 8 | |

| Unspecified/other | 19 | |

| Publicness of setting | Completely public | 2 |

| Public in experiment | 1 | |

| Supposedly private, but done in presence of others | 30 | |

| Completely private, except for experimenter | 22 | |

| Completely private | 14 | |

| Unspecified | 32 | |

| Filler items | Filler items present | 37 |

| Filler items not present | 52 | |

| Unspecified | 12 | |

| Type | Likert scale | 57 |

| Feeling thermometer | 4 | |

| Semantic differential | 2 | |

| Thurstone | 4 | |

| Lexical decision/word completion/IAT | 5 | |

| Mixed/other | 5 | |

| Unspecified | 15 | |

| Explicit vs. implicit | Explicit | 95 |

| Implicit | 6 | |

| Attitude object | Outgroup in general | 39 |

| Specific outgroup member(s) | 6 | |

| Policy toward outgroup (outgroup specified during measurement) | 14 | |

| Policy affecting outgroup (outgroup not specified during measurement) | 2 | |

| Outgroup and outgroup policy | 23 | |

| Mixed/other | 17 | |

| Unspecified | 5 | |

| Groups presented | Outgroup only | 69 |

| Multiple outgroups only | 12 | |

| Outgroup and ingroup | 13 | |

| Multiple outgroups and ingroup | 1 | |

| Multiple outgroups and neutral group | 2 | |

| Unspecified | 4 | |

| Abstractness | Abstract | 66 |

| Somewhat concrete (a fictional person or policy loosely realized) | 12 | |

| Fairly concrete (a fictional person or policy well-realized) | 5 | |

| Concrete | 10 | |

| Mixed/unspecified | 8 | |

| Valence | Positive | 7 |

| Negative | 29 | |

| Both/indiscriminate | 57 | |

| Unspecified | 8 | |

Note: k = number of studies

Discrimination

We coded 92 instances of discrimination measurement, again including those from the six interaction-effect studies for which an r could not be computed. Table 6 shows frequencies for all characteristics.

Table 6.

Summary of behavior measurement characteristics

| Variable | Class | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Median number of behavior items | 2 | |

| k | ||

| Contact during measurement | Outgroup member present during measurement | 33 |

| Outgroup member in next room | 9 | |

| Outgroup member not present during measurement | 42 | |

| Unspecified | 8 | |

| Contact within measure | Contact implied by measure | 46 |

| Contact possibly implied | 13 | |

| Contact not implied | 37 | |

| Immediacy of measured behavior | Physical action | 56 |

| Paper-and-pencil action | 22 | |

| Paper-and-pencil commitment to later physical action | 18 | |

| Setting | Laboratory | 66 |

| Phone survey | 2 | |

| Interview survey | 4 | |

| Field | 2 | |

| Mail survey | 6 | |

| Phone or mail survey | 2 | |

| Unspecified/other | 14 | |

| Publicness | Public to public at large | 18 |

| Public within experiment | 39 | |

| Supposedly private, but done in the presence of others | 20 | |

| Completely private, except for experimenter | 14 | |

| Privacy varies from public at large | 3 | |

| Unspecified/other | 2 | |

| Object | Specific outgroup member(s) | 54 |

| Outgroup in general | 35 | |

| Policy toward outgroup (outgroup specified during measurement) | 3 | |

| Policy affecting outgroup (outgroup not specified during measurement) | 3 | |

| Outgroup and outgroup policy | 1 | |

| Targets presented to each participant | Outgroup only | 59 |

| Outgroup and ingroup | 34 | |

| Multiple outgroups only | 3 | |

| Abstractness of behavior target | Abstract | 22 |

| Somewhat concrete (a fictional person or policy loosely realized) | 4 | |

| Fairly concrete (a fictional person or policy well-realized) | 21 | |

| Concrete | 48 | |

| Mixed/unspecified | 1 | |

| Nonverbal | Verbal | 83 |

| Non-verbal and verbal | 7 | |

| Non-verbal | 5 | |

| Immediacy | Measured behavior directly affected target | 54 |

| Behavior performed directly affected target in next room | 10 | |

| Behavior did not directly affect target | 32 | |

| Valence | Positive | 44 |

| Negative | 17 | |

| Both | 35 | |

| Time of behavior | Past behavior | 20 |

| During study | 53 | |

| Commitment to later behavior, with ramifications | 17 | |

| During study and commitment to later behavior | 3 | |

| During study and intention to later behavior without ramifications | 3 | |

| Judgment method | Trained judges | 7 |

| Experimenter | 1 | |

| Confederate | 1 | |

| Peer observer | 1 | |

| Objective measure (e.g., seating distance) | 33 | |

| Objective measure from self-report (e.g., number of outgroup members hired) | 15 | |

| Self-report | 37 | |

| Behavior-evaluation | Behavior toward outgroup member | 83 |

| Evaluation of outgroup member | 12 | |

| Mixed | 1 |

Note: k = number of studies

Effect Size Characteristics

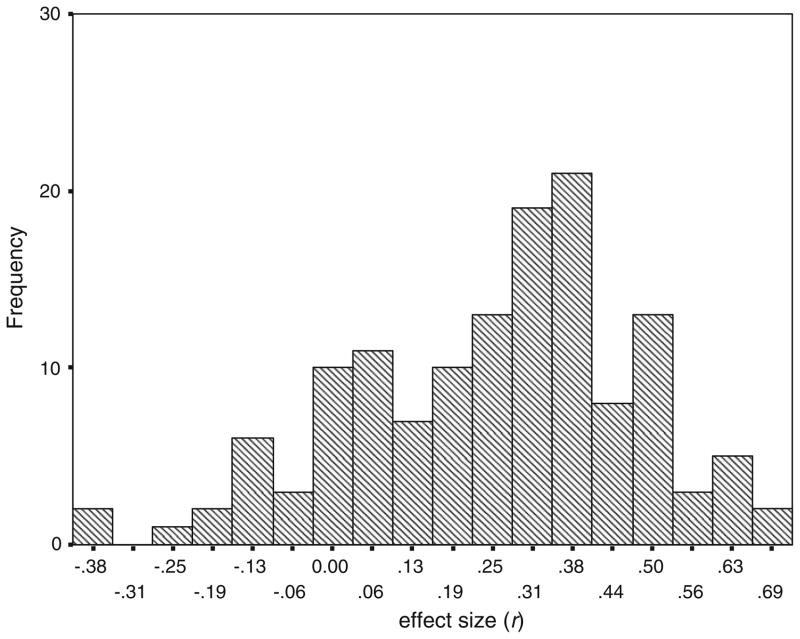

As stated, we included an effect size for each attitude-discrimination pair available, and so more than one effect size was included from certain studies. The authors, year, and the names of the attitude and behavior measures for each effect are shown in the Appendix. The distribution of the 136 effect sizes used for analysis is shown in Fig. 1. The distribution of the z-transformed effect sizes (corrected for the non-normality of r) revealed a bimodal distribution suggesting some variability in the effect sizes.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of r. N = 136

Overall Relationship Between Attitude and Discrimination

The overall mean weighted effect size for the attitude-discrimination relationship was r = .264, 95% CI = .229–.298. As expected, this relationship was heterogeneous across studies, Q(135) = 727.13, p < .001. These overall results use the random-effects model, as we believed that the differences between the different effect-size estimates could not be attributed solely to subject-level sampling error.

Regarding moderator analyses, we believed that the variance between studies could be due to factors beyond those that we chose to code in the current meta-analysis because the studies chose to measure attitudes and behavior in such different manners. Therefore, we conservatively used mixed-effects models to estimate all regression coefficients for moderators, differences between subgroups based on moderators, and weighted rs for these sub-groups (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).

Effects of Attitude Focus on Relationship Between Attitude and Discrimination

First, we looked at the descriptive statistics for effect sizes grouped by our most precise categorization of attitudinal focus. The Mdn r, rmax, rmin, and k, the number of studies in each category appear in Table 7. The emotion-focus studies have effect sizes most similar to the behavioral-intention focus studies. That is, measuring emotional prejudices falls quite close to measuring discriminatory intentions, a result confirming our predictions.

Table 7.

Median, minimum, and maximum r for studies using different attitude measurement foci, in descending order of median r

| Attitude focus | Median | Minimum | Maximum | k |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioroid | .39 | −.10 | .63 | 10 |

| Emotion | .35 | .23 | .63 | 11 |

| Emotion and overall valence | .32 | .13 | .42 | 8 |

| Mixed/other | .31 | −.36 | .69 | 50 |

| Stereotype | .26 | .25 | .26 | 2 |

| Stereotype and overall valence | .24 | −.15 | .55 | 6 |

| Overall valence | .12 | −.06 | .48 | 7 |

| Belief and stereotype | .12 | −.15 | .51 | 9 |

| Belief | .08 | −.37 | .54 | 27 |

Note: k = number of studies

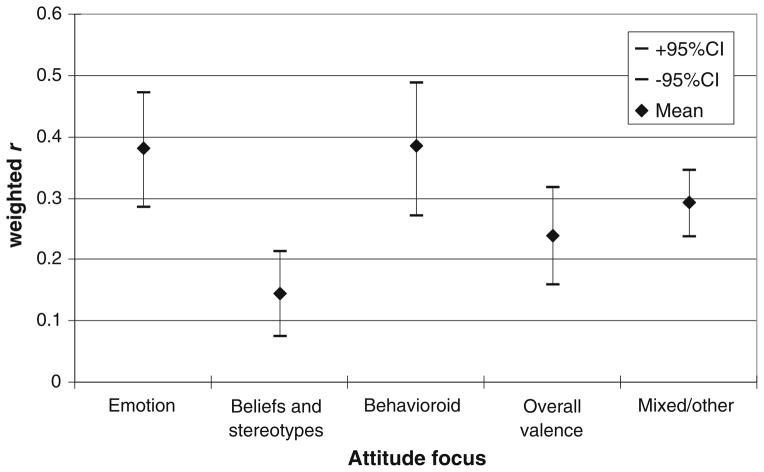

Because only two studies measured stereotypes separately from beliefs, we collapsed the three cognitive categories of attitude—stereotypes, beliefs, and stereotypes and beliefs—to create a “stereotypes and/or beliefs” category. The median r for the emotion-focus studies is greater than for all the other attitude measures except the behavioral intentions (see Fig. 2). Using the meta-analytic analog to ANOVA (restricted-information maximum likelihood model), we found a significant difference between all of these groups, Q(4, 131) = 24.16, p < .001.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of effect sizes by attitude focus

A direct comparison of the emotion-focused studies with the stereotypes and/or belief-focused studies (ignoring all other studies) revealed that these two categories significantly differed from each other, Q(1, 49) = 16.66, p < .001.

Another concern is that the emotional versus cognitive focus of the attitude measure might be confounded with such methodological factors as year, and thus perhaps with study quality. So, we did an inverse-variance-weighted multiple regression of study year, number of attitude items (log transformed to correct for skew), number of behavior items, whether attitude and discrimination were measured on the same day, and whether they were measured in the same study, all on the z-transformed effect size. It was impractical to perform regressions with more than these predictors, due to the small number of studies using emotional measures and the regularity with which some factors were reported. As Table 8 shows, the emotional prejudices exhibit a significantly higher relation to discrimination than cognitive measures do, even controlling for pertinent methodological factors.

Table 8.

Standardized regression coefficients for emotion versus belief/stereotype focus, controlling for methodological factors

| β | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotion vs. belief/stereotype focus | .32 | .00 |

| Year | −.17 | .07 |

| Number of behavior items | −.16 | .06 |

| Number of attitude items (log transformed) | .04 | .67 |

| Attitude and behavior measured in same study | .03 | .77 |

| Time between attitude and behavior measurement | −.02 | .85 |

Note: k = 123

Behavior Directness

All behavior directness characteristics were contrast coded or assigned Likert-type scale points as shown in Tables 2 and 3. All measures were coded such that higher numbers mean more directness. These factors significantly predicted differences in the strength of the attitude–behavior relationship, R2 = .21, Q(9, 113) = 32.28, p < .01. The independently significant predictors were the activeness (paper-and-pencil task versus physical action), time (during study versus past behavior versus commitment to later behavior), judgment method (objective versus self-report), and the abstractness of the behavior target (Table 9). Among the significant predictors, the direction of relationship was not consistent, as might be expected, given that they are measuring closely related concepts.

Table 9.

Standardized regression coefficients, in descending order of significance, for all behavior directness variables

| β | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Activeness | −.49 | .00 |

| Time | .47 | .00 |

| Publicness | .25 | .01 |

| Judgment method | −.35 | .02 |

| Abstraction | −.23 | .03 |

| Action vs. evaluation | .21 | .08 |

| Contact implied by measure | .17 | .18 |

| Contact during measurement | −.17 | .18 |

| Contingency | .15 | .26 |

Note: k = 123

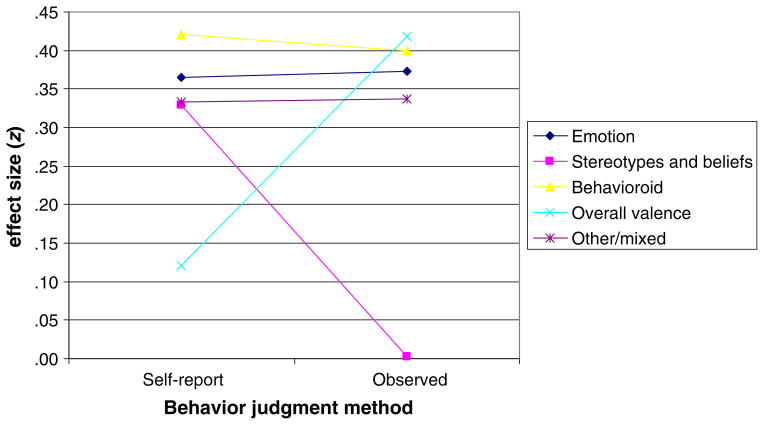

Interaction of Behavior Directness with Attitude Focus

Because so few studies used emotion-focused attitude measures, detailed analysis of the interaction between this variable and behavior directness was not plausible. To simplify analyses, we chose the most effective two-category indicator of behavior directness, the method of behavior judgment (self-report versus judged/objective), and analyzed its interaction with attitude focus. Figure 3 shows no difference between the median z for self-reported and for observed behaviors among studies using emotional, behavioroid, and mixed-focus attitude measures. These more immediate measures, then, are robust with regard to behavioral measure.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of attitude focus and behavior judgment method

For stereotypes and beliefs, however, the median effect size for studies using self-report measures is z = .33, similar to the median affect sizes for other foci. But, as predicted for the more direct behavior measures, the correlation was reduced; for observed behaviors, Mdn z = .00. Interestingly, an unpredicted opposite interaction was found within the overall-valence-focus measures.

Discussion

Returning to Allport’s comment that what people do to outgroups is not always related to what they think and feel, we now know that what they do is substantially related to how they feel, and somewhat related to how they think. Emotional prejudices felt toward racial minority outgroups are more closely related to discrimination than are beliefs and stereotypes thought about them. The difference between the strength of these relationships is not diminished by controlling for other methodological factors. In fact, emotional prejudices are almost as closely related to discriminatory behavior as discriminatory intentions are. These results fit past theory and research suggesting that emotions are important in determining behavior in general (Abelson et al., 1982; Frijda, 1986; Izard & Ackerman, 2000; LeDoux, 1996; Mandler, 1992; Panksepp, 2000; Zajonc, 1998) and in particular, discrimination based on sexual orientation [Talaska et al. (2003). Emotional prejudices, stereotypes, and attitudes in the prediction of discrimination. Unpublished manuscript, Princeton University]. Given these findings, the analysis of intergroup emotions offers possibilities for further understanding discrimination, a point that fits the new conventional wisdom about intergroup relations (Mackie & Smith, 2002).

What then do stereotypes do? Perhaps they operate as part of a conscious ideological system. Stereotypes and beliefs equal emotional prejudices as predictors of self-reported discrimination, but less closely relate to observed discrimination. Thus, stereotypes, beliefs, and emotional prejudices all closely relate to what people say they did or will do toward outgroup members, but emotional prejudices are more closely related to what people actually do.

In many of the reviewed studies, researchers tend to present their findings as representing racial attitude–behavior relations in general. Our findings suggest that racial attitude researchers should take more seriously the discrimination measure that they use to validate their measures. In an ideal world, perhaps one would decree “standard” measures of discrimination. However, we lack the perfect measure of discrimination (Panel on Methods for Assessing Discrimination, 2004). Moreover, the motivations behind different types of discrimination could quite possibly differ. The motivations behind helping differ from the motivations behind harming (Cuddy et al., 2007). The motivations behind an employer overlooking a Black candidate probably differ from those behind someone using racial epithets, which in turn differ from those behind someone beating up a Black person. A more realistic choice is for researchers to decide what precise type of discrimination they want to understand better and to design the most realistic way to capture that type in the laboratory. In any event, behavioral directness does matter, even in the broad-brush distinction between observed versus self-report.

What implications does the modest relationship between beliefs or stereotypes and discrimination have for the study of bias? Many of the belief measures of attitude (e.g., McConahay, 1986) were developed to get around social desirability concerns and demand characteristics aroused by even more explicit measures of racial attitude. But apparently they do not go far enough. Perhaps belief-measurement could borrow from behavior measurement. We know that making people feel responsible for their reports of behavioral intentions (e.g., by telling them that their responses will affect selection of their future college roommate; Silverman, 1974) brings those reports closer to actual behaviors. Similarly, perhaps making people feel more responsible for their reports of attitude will bring these reports closer to approximating people’s most predictive attitudes. Researchers should attempt to assess the “truest” attitude they can for their own purposes. One way to define true attitudes is those that lead to discrimination. Under this definition, emotional prejudices just may be another way to get at truer inter-racial attitudes.

Limitations and Future Directions

One major impediment to this meta-analysis was the lack of consistency in the methods used in past racial attitude-discrimination studies. These studies vary wildly in their methods for measuring attitude and discrimination and in overall quality. This diversity may have masked some moderators of the racial attitude–behavior relationship. For example, the congruency between attitude and behavior targets has a large influence on the strength of the relationship (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Congruency did vary between studies, and may have enhanced or detracted from observed moderators. Analysis controlling for all relevant differences between studies is impossible, especially given our next limitation.

The detail with which these methods were reported was also not ideal. Some possible moderators, such as the reliability of the attitude measure, had to be discarded because so few studies reported them. The moderators that were available were not reported in all studies. This lack in reporting may be confounded with other study factors, such as year and study quality, again biasing our findings.

Another limiting factor of the current analysis was that few studies use differentiated emotional prejudices to predict discrimination. Thus, the current meta-analysis was undertaken in the hopes that researchers will begin to use the valuable tool of emotional prejudices more regularly and differentiated emotional prejudices in particular, which have proved useful in other work predicting discriminatory tendencies (Cuddy et al., 2007). So, necessary further research will illuminate the conditions under which stereotypes, beliefs, and differentiated emotional prejudices best predict discrimination.

The central role of emotions and the diminished role of beliefs suggest that people may recruit beliefs as a post-hoc justification for their own emotion-driven behavior. A person has an aversion response (disgust), avoids sitting next to a racial outgroup member on the subway, notices the behavior, and justifies it. More seriously, an employer responds with pride to an ingroup candidate and with ambivalence (pity, resentment) or even contempt to an outgroup candidate, and the employment results are clear. Emotions are intrinsically more difficult to examine, both for the holder of emotions and for the scientific observer.

Emotion-based discrimination is ripe for further study. The questions, for example, of what sort of attitudes predict what sorts of discrimination, and when do they do so, also merit further investigation. Answers to these questions, along with further investigation of emotional prejudices, may take us further in Allport’s—and all of our—quest to undermine discrimination and increase social justice.

Appendix: Authors and Measures for Each Effect Size

| Study authors | Year | Attitude measure | Behavior measure | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bastide & Van Den Berghe | 1957 | Hypothetical behavior | Actual past behavior | .490 |

| Social norms of behavior (“Should” scale) | Actual past behavior | .510 | ||

| Stereotype inferiority or superiority | Actual past behavior | .250 | ||

| Berg | 1966 | E Scale Negro | Autokinetic judgment | −.210 |

| F Scale | Autokinetic judgment | −.140 | ||

| Social distance | Autokinetic judgment | −.100 | ||

| Brannon et al. | 1973 | Belief about whether problems occur when Negroes move into a neighborhood | Signing to open housing petition and public support | .213 |

| Housing law survey question | Signing to open housing petition and public support | .506 | ||

| Negative stereotyping | Signing to open housing petition and public support | .263 | ||

| Bray | 1950 | Attitude to Jews (Levinson-Sanford scale, 16 items) | Autokinetic influence by Jewish confederate | −.149 |

| Likert scale of attitude toward the Negro (Likert, 1932) | Autokinetic influence by Black confederate | .108 | ||

| Brief, Dietz, Cohen, Pugh, & Vaslow. Study one | 2000 | Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) | Number of Black applicants selected for job interview (marketing rep.) | .062 |

| Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) | Number of Black applicants selected for job interview (marketing rep.) | .378 | ||

| Brief et al., study two | 2000 | Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) | Applicant quality rating in “managerial decision making” role play | .309 |

| Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) | Applicant quality rating in “managerial decision making” role play | .333 | ||

| Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) | Applicant quality rating in “managerial decision making” role play | −.034 | ||

| Brigham, sample two | 1993 | Affective/Semantic differential factor | Current other-race friends | .280 |

| Affective/Semantic differential factor | Current day-to-day other race contact (fairly voluntary) | .310 | ||

| Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Current day-to-day other race contact (fairly voluntary) | .170 | ||

| Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Current other-race friends | .180 | ||

| Modern Racism (McConahay, Hardee, & Batts, 1981)—1 item (like Weigel & Howes, 1985) | Current day-to-day other race contact (fairly voluntary) | .040 | ||

| Modern Racism (McConahay et al., 1981)—1 item (like Weigel & Howes, 1985) | Current other-race friends | .080 | ||

| MRAI (Brigham, Woodmansee, & Cook, 1976) | Current day-to-day other race contact (fairly voluntary) | .180 | ||

| MRAI (Brigham et al., 1976) | Current other-race friends | .220 | ||

| Symbolic Racism (Kinder, 1981; minus 2 of five busing items; minus 2 items that “differed in format”) | Current day-to-day other race contact (fairly voluntary) | −.020 | ||

| Symbolic Racism (Kinder, 1981; minus 2 of five busing items; minus 2 items that “differed in format”) | Current other-race friends | −.020 | ||

| Burnstein & McRae | 1962 | Holtzman desegregation scale (Kelly, Ferson, & Holtzman, 1958) | Choosing to replace Negro confederate | .320 |

| Holtzman desegregation scale (Kelly et al., 1958) | Evaluation of Negro confederate’s likeability | .204 | ||

| Holtzman desegregation scale (Kelly et al., 1958) | Evaluation of Negro confederate’s contribution to task | .353 | ||

| Holtzman desegregation scale (Kelly et al., 1958) | Percentage of communications sent to Negro confederate | .297 | ||

| DeFleur & Westie | 1958 | Summated difference scales | Photo authorization | .397 |

| DeFriese & Ford | 1969 | Thurstone attitude | Signing public open housing or closed housing petition | .390 |

| Dijker | 1987 | Surinamer anxiety mood and tendency | Surinamer contact | .340 |

| Surinamer concern mood and tendency | Surinamer contact | .400 | ||

| Surinamer feeling thermometer | Surinamer contact | .420 | ||

| Surinamer irritation mood and tendency | Surinamer contact | .390 | ||

| Surinamer positive mood and tendency | Surinamer contact | .600 | ||

| Turk anxiety mood and tendency | Turk/Moroccan contact | .270 | ||

| Turk concern mood and tendency | Turk/Moroccan contact | .360 | ||

| Turk irritation mood and tendency | Turk/Moroccan contact | .350 | ||

| Turk positive mood and tendency | Turk/Moroccan contact | .630 | ||

| Turk/Moroccan feeling thermometer | Turk/Moroccan contact | .300 | ||

| Dovidio & Gaertner | 2000 | Racial attitude items (Weigel & Howes, 1985) | Counseling candidate evaluation | .240 |

| Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner | 2002 | Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Non-verbal behavior friendliness | .020 |

| Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Self-reported friendliness | .330 | ||

| Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Verbal behavior friendliness | .400 | ||

| Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Confederate-reported friendliness | −.140 | ||

| Brigham’s (1993) Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | Overall observed friendliness | −.120 | ||

| Implicit attitudes decision task | Overall observed friendliness | .430 | ||

| Implicit attitudes decision task | Confederate-reported friendliness | .400 | ||

| Implicit attitudes decision task | Self-reported friendliness | .050 | ||

| Implicit attitudes decision task | Verbal behavior friendliness | .040 | ||

| Implicit attitudes decision task | Non-verbal behavior friendliness | .410 | ||

| Dovidio et al., study three | 1997 | Modern Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Visual contact time in interview (Black vs. White) | −.200 |

| Modern Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Evaluations of interviewer (White vs. Black) | .540 | ||

| Modern Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Self-evaluations of sincerity and likeableness in interviews (White vs. Black) | .370 | ||

| Modern Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Blinking rate in interview (Black vs. White) | .070 | ||

| Old-Fashioned Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Blinking rate in interview (Black vs. White) | −.040 | ||

| Old-Fashioned Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Evaluations of interviewer (White vs. Black) | .370 | ||

| Old-Fashioned Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Visual contact time in interview (Black vs. White) | −.020 | ||

| Old-Fashioned Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Self-evaluations of sincerity and likeableness in interviews (White vs. Black) | .120 | ||

| Response-latency bias | Evaluations of interviewer (White vs. Black) | .020 | ||

| Response-latency bias | Blinking rate in interview (Black vs. White) | .430 | ||

| Response-latency bias | Visual contact time in interview (Black vs. White) | .400 | ||

| Response-latency bias | Self-evaluations of sincerity and likeableness in interviews (White vs. Black) | .070 | ||

| Dovidio et al., study two | 1997 | Modern Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Juridic judgment | .380 |

| Old-Fashioned Racism scale (McConahay, 1986) | Juridic judgment | .510 | ||

| Response-latency bias | Juridic judgment | .020 | ||

| Word-completion task (from Gilbert & Hixon, 1991) | Juridic judgment | −.150 | ||

| Ewens & Ehrlich | 1972 | Adjective checklist (affective, conative, cognitive) | Survey interviewing | .299 |

| Adjective checklist (affective, conative, cognitive) | Newspaper statement—civil rights activities | .144 | ||

| Adjective checklist (affective, conative, cognitive) | Civil rights group—civil rights activities | .325 | ||

| Adjective checklst (affective, conative, cognitive) | Civic talk—civil rights activities | .483 | ||

| Adjective checklist (affective, conative, cognitive) | Protest march—civil rights activities | .324 | ||

| Fendrich | 1967b | 32 item verbal attitudes | Commitment to interracial and civil rights behavior | .430 |

| 32 item verbal attitudes | NAACP group discussions and civil rights activities | .694 | ||

| 32 item verbal attitudes | Commitment to interracial and civil rights behavior | .676 | ||

| 32 item verbal attitudes | NAACP group discussions and civil rights activities | .081 | ||

| Fendrich | 1967a | 32 item verbal attitudes | NAACP group discussions and civil rights activities | .476 |

| Genthner & Taylor | 1973 | Holtzman Desegregation Scale | Selected shock intensity for Black confed | .509 |

| Green | 1972 | MRAI (Woodmansee & Cook, 1967) | Photo authorization | .394 |

| Harkins & Becker, study 2 | 1979 | Prejudice self-rating | photo authorization | .060 |

| Hendricks | 1976 | Discomfort level at closeness to Black confederate | Seating choice with Black confederate | .323 |

| Himelstein | 1963 | Adaptation of Adorno’s Authoritarian personality scale | Petition signing, confed no sign | −.228 |

| Himelstein & Moore | 1963 | Adaptation of Adorno’s Authoritarian personality scale | Petition signing, confed sign | .209 |

| Howitt & McCabe | 1978 | Attitudes on Northern Ireland | Misdirected Irish letter returning | .599 |

| Islam & Hewstone | 1993 | Intergroup anxiety (Stephan & Stephan, 1985) | Amount of contact | .230 |

| Overall attitude | Amount of contact | −.058 | ||

| Perceived out-group variability | Amount of contact | .460 | ||

| Jackman | 1976 | Government Action (applied policy orientation toward Blacks) | Vote for Wallace (anti-civil- rights candidate) | .179 |

| Intention to vote for Wallace | Vote for Wallace (anti-civil-rights candidate) | .506 | ||

| Segregationism (genereralized policy orientation) | Vote for Wallace (anti-civil-rights candidate) | .196 | ||

| Temperature toward Blacks | Vote for Wallace (anti-civil-rights candidate) | .129 | ||

| Temperature towards Wallace | Vote for Wallace (anti-civil-rights candidate) | .251 | ||

| Kamenetzky, Burgess, & Rowan | 1956 | Agreement with employment discrimination statements (Likert version) | Fair employment petition | .610 |

| Responses to anti-Black cartoons | Fair employment petition | .540 | ||

| Katz | 1975 | Causes of minority people’s problems | Compliance with Negro student doing “consumer attitude” survey (phone) | −.366 |

| Kelly, Ferson, & Holtzman | 1958 | Holtzman Desegregation scale | Been the guest of a Negro in his house | .210 |

| Holtzman Desegregation scale | Belonged to social club or attended social gathering | .340 | ||

| Holtzman Desegregation scale | Played together as small children | .330 | ||

| Holtzman Desegregation scale | Played together as small children | .300 | ||

| Holtzman Desegregation scale | Played together as small children | .170 | ||

| Linn | 1965 | I wouldn’t mind social distance scale | Photo authorization | .288 |

| Willingness to be in interracial opposite-sex photo with varying publicity levels | Photo authorization | .389 | ||

| Mabe & Williams | 1975 | PRAM II (Williams, Best, & Boswell, 1975) | Who would you like to sit by/work with/play with sociometry | .550 |

| Malof & Lott | 1962 | E Scale Negro | Asch minority influence | .420 |

| Masson & Verkuyten | 1993 | Prejudicial attitudes in general (DeJong & Van Der Toorn, 1984) | Rate of weekly contact | .330 |

| McConahay | 1983 | Modern Racism (McConahay et al., 1981)—1 item (like Weigel & Howes, 1985) | Hiring role-play: “Would you hire this person?” | .500 |

| McConnell | 2001 | Racially associated name IAT (Whites–Blacks) | Experimenters’ ratings of 4-question interview—eye contact, abruptness/curtness, friendliness, and general comfort level | .390 |

| McConnell & Leibold | 2001 | Racially associated name IAT (Whites–Blacks) | Trained judges’ ratings—abruptness/curtness, friendliness, and general comfort level | .340 |

| Semantic differential and feeling thermometer (Whites–Blacks) | Trained judges’ ratings—abruptness/curtness, friendliness, and general comfort level | .260 | ||

| Semantic differential and feeling thermometer (Whites–Blacks) | Experimenters’ ratings of 4-question interview—eye contact, abruptness/curtness, friendliness, and general comfort level | .330 | ||

| Montgomery & Enzie | 1973 | Steckler’s attitudes toward Negroes scale and rev. E scale | Autokinetic influence by Black confederate | .066 |

| Plant & Devine, study two | 2001 | Angry/threatened affect at boss’ suggestion IMS × EMS | Hiring candidate after pro-Black pressure removed | .390 |

| Hiring candidate after pro-Black pressure removed | .477 | |||

| Raden | 1980 | F Scale (5-items; Srole, 1956) | Selected shock intensity for White or Black confed | .242 |

| Saenger & Gilbert | 1950 | Attitudes toward Negro salespersons; interview prejudice rating | Race of store clerk approached | .047 |

| Attitudes toward Negro salespersons; question | Race of store clerk approached | .005 | ||

| Sappington | 1974 | Civil rights liberal or conservative | Non-immediacy of hypothetical remarks to videotaped discussion participants | .496 |

| Civil rights liberal or conservative | Consultant preference (hypothetical) | .394 | ||

| Civil rights liberal or conservative | Proportion responses to Black man in hypothetical remarks to videotaped discussion participants | .440 | ||

| Silverman & Cochrane | 1971 | Open housing behavioral intention | Open housing petition | .380 |

| Open housing petition behavioral intention | Open housing petition | .630 | ||

| Smith & Dixon | 1968 | E Scale Negro | Verbal conditioning to Black expt’r | .000 |

| Vorauer | 2001 | Manitoba Prejudice scale (Altemeyer, 1988) | Affective reaction of interaction partner | .530 |

| Wagner, Hewstone, & Machleit | 1989 | How likeable item | Contact during school break | .120 |

| How likeable item | Friends from the outgroup | .270 | ||

| How likeable item | Contact during leisure time | .480 | ||

| How likeable item | Visits at the house (number) | .240 | ||

| How likeable item | Informal talks (number) | .010 | ||

| Warner & DeFleur | 1969 | Verbal attitude | Public signing or refusal to social-distance maintaining act | .262 |

| Verbal attitude | Private signing or refusal to social-distance reducing act | .002 | ||

| Verbal attitude | Public signing or refusal to social-distance reducing act | .124 | ||

| Verbal attitude | Private signing or refusal to social-distance maintaining act | .103 | ||

| Weatherley | 1987 | Levinson Anti-Semitism Scale | Fantasy aggression toward Jewish-named characters in story | .396 |

| Weitz | 1972 | How friendly will you feel toward imaginary Black “subject” in 1 year | Seating distance | −.362 |

Footnotes

Like bias researchers, attitude researchers have also noted the neglect of emotional predictors in their field (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993).

Ajzen and Fishbein’s (1977) model posited that the attitude toward the behavior influenced the behavioral intention, which in turn affected the behavior. Both the attitude toward the behavior and the intention are affected by other factors, such as the social norms in regard to the behavior.

Because of the social desirability issues involved in inter-racial interaction, we coded social desirability pressures on both attitude and behavior measurement, but they had no effect on the attitude-discrimination relationships, so we do not discuss these results, which are however available from the second author (Fiske).

Problems with coding the third type of study—converting these latter results to a simple correlational effect size—concerned whether we want to convert the information into an effect of the first (attitude relating to between-subjects differences in behavior) or the second (attitude relating to within-subjects differences in ingroup versus outgroup behavior) type. Because the current type is based on a between-subjects error term, difficulties arise in converting the effect into one of the second type, which is based on a within-subjects error term, as not enough information was present to correct for the differences in statistics based on between- versus within-subjects error terms. So, the interaction effects were converted to the first type of effect by looking at the relationship between attitude and behavior in the outgroup behavior condition only, and ignoring all of the subjects that were in the ingroup behavior condition. However, for six of the studies reporting an interaction effect, not enough information was present to recode this effect as an r (either the effect was reported only as nonsignificant or only as the F for the interaction without any other information). However, in converting these effects, we are ignoring the relation of the attitude measure to ingroup behavior, and thereby losing possibly valuable information, especially when they found a main effect of attitude on behavior for outgroup and for ingroup targets (e.g., Genthner & Taylor, 1973). So, the size of the correlations in the studies that measured behavior toward outgroup targets only, without reference to behavior toward ingroup targets, may be inflated by this phenomenon. This finding questions the meaning of studies that measure behavior toward outgroup members only. Perhaps some attitude measures simply predict who will be more or less aggressive or conformist, rather than who will behave in a specifically prejudiced manner.

Contributor Information

Cara A. Talaska, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Susan T. Fiske, Email: sfiske@princeton.edu, Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Green Hall 2-N-14, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA

Shelly Chaiken, Berkeley, CA, USA.

References

*indicates study included in meta-analysis (see Appendix)

- Abelson RP, Kinder DR, Peters MD, Fiske ST. Affective and semantic components in political person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;42:619–630. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;84:888–918. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Malden, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer B. Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- *.Bastide R, Van Den Berghe P. Stereotypes, norms and interracial behavior in Sao Paulo, Brazil. American Sociological Review. 1957;22:689–694. [Google Scholar]

- *.Berg KR. Ethnic attitudes and agreement with a Negro person. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;4:215–220. doi: 10.1037/h0023560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen GV, Moreno KN. How do I feel about them? The role of affective reactions in intergroup perception. In: Bless H, Forgas JP, editors. The message within: The role of subjective experience in social cognition and behavior. Philadelphia: Psychology Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bogardus ES. A social distance scale. Sociology & Social Research. 1933;17:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- *.Brannon R, Cyphers G, Hesse S, Hesselbart S, Keane R, Schuman H, et al. Attitude and action: A field experiment joined to a general population survey. American Sociological Review. 1973;38:625–636. [Google Scholar]

- Branthwaite A, Jones JE. Fairness and discrimination: English versus Welsh. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1975;5:323–338. [Google Scholar]

- *.Bray DW. The prediction of behavior from two attitude scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1950;45:64–84. doi: 10.1037/h0059529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brief AP, Dietz J, Cohen RR, Pugh SD, Vaslow JB. Just doing business: Modern racism and obedience to authority as explanations for employment discrimination. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2000;81:72–97. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1999.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brigham JC. College students’ racial attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1993;23:1933–1967. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham JC, Woodmansee JJ, Cook SW. Dimensions of verbal racial attitudes: Interracial marriage and approaches to racial equality. Journal of Social Issues. 1976;32:9–21. [Google Scholar]

- *.Burnstein E, McRae AV. Some effect of shared threat and prejudice in racially mixed groups. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1962;64:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH. The psychology of aggression. New York: Wiley; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG. The affect system: Architecture and operating characteristics. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S, Trope Y, editors. Dual-process theories in social psychology. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Clark EM, Brock TC. Administration of physical pleasure as a function of recipient race, attitude similarity, and attitudes toward interracial marriage. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1992;13:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F, Bromley S, Saxe L. Recent unobtrusive studies of Black and White discrimination and prejudice: A literature review. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:546–563. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 40. New York, NY: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 61–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Kwan VSY, Glick P, Demoulin S, Leyens J-Ph, et al. Is the stereotype content model culture-bound? A cross-cultural comparison reveals systematic similarities and differences. British Journal of Social Psychology in press. [Google Scholar]

- DeCoster JC. Meta-analysis notes. 2001 http://www.stat-help.com/meta.pdf.

- *.DeFleur ML, Westie FR. Verbal attitudes and overt acts: An experiment on the salience of attitudes. American Sociological Review. 1958;23:667–673. [Google Scholar]

- *.DeFriese GH, Ford WS. Verbal attitudes, overt acts, and the influence of social constraint in interracial behavior. Social Problems. 1969;16:493–505. [Google Scholar]