Abstract

Background

Gender-specific anthropometrics, skin texture/adnexae mismatch, and social apprehension have prevented cross-gender facial transplantation from evolving. However, the scarce donor pool and extreme waitlist times are currently suboptimal. Our objective was to: 1) perform and assess cadaveric facial transplantation for each gender-mismatch scenario employing virtual panning with cutting guide fabrication and 2) review the advantages/disadvantages of cross-gender facial transplantation.

Methods

Cross-gender facial transplantation feasibility was evaluated through two mock, double-jaw, Le Fort-based cadaveric allotransplants, including female donor-to-male recipient (T1-FM) and male donor-to-female recipient (T2-MF). Hybrid facial-skeletal relationships were investigated using cephalometric measurements, including sellion-nasion-A point (SNA) and sellion-nasion-B point (SNB) angles, and lower-anterior-facial-height to total-anterior-facial-height ratio (LAFH/TAFH). Donor and recipient cutting guides were designed with virtual planning based on our team’s experience in swine dissections and used to optimize the results.

Results

Skeletal proportions and facial-aesthetic harmony of the transplants [n=2] were found to be equivalent to all reported experimental/clinical gender-matched cases by using custom guides and Mimics technology. Cephalometric measurements are shown in Table 1 relative to Eastman Normal Values.

Conclusions

Based on our results, we believe that cross-gender facial transplantation can offer equivalent, anatomical skeletal outcomes to those of gender-matched pairs using pre-operative planning and custom guides for execution. Lack of literature discussion of cross-gender facial transplantation highlights the general stigmata encompassing the subject. We hypothesize that concerns over gender-specific anthropometrics, skin texture/adnexae disparity, and increased immunological resistance have prevented full acceptance thus far. Advantages include an increased donor pool with expedited reconstruction, as well as size-matched donors.

Keywords: Face Transplant, Craniomaxillofacial, Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation (VCA), Gender, Cross-gender, Intraoperative Cutting Guide

INTRODUCTION

Craniomaxillofacial transplantation is a clinical reality that is rapidly gaining acceptance as a suitable alternative to autologous methods for reconstructing massive facial skeletal defects not amenable to standard techniques. As the world continues to gain experience in facial transplantation, indications will broaden as the procedure emerges from its designation as experimental to standard of care in select patients. Furthermore, advances in immunotherapy, including concurrent donor bone marrow augmentation for immunosuppression minimization (1), will aid in reducing the requirements for intensive lifelong immunosuppressant regimens. The combination of increased experience, widespread public acceptance, and reduced immunosuppression will further place the limitation of this surgical procedure on donor supply, as seen with solid organ transplantation.

For some programs, a gender mismatched donor/recipient pair has been listed as a contraindication to craniomaxillofacial transplantation (2). Gender specific anthropometrics and skin/hair aesthetic mismatch have led to concerns that cross-gender facial transplants will produce inferior hybrid results. However, removing the gender barrier in craniomaxillofacial transplantation would significantly increase the donor pool, providing patients with massive facial skeletal defects with more options for reconstruction. In addition, cross-gender donors could potentially provide appropriately sized donors that may not be available in their gender-matched counterparts.

Donor-to-recipient matching in facial transplantation is confined not only by blood type compatibility and cross matching, but also by phenotypic characteristics and viral mismatch status (3,4). We believe that skeletal size matching should be weighed heavily when matching donors and recipients, and that strict rules concerning gender matching should be avoided. Furthermore, employing virtual surgery pre-transplant following donor identification and utilizing intra-operative cutting guides will greatly assist the craniofacial team.

Such considerations have already been demonstrated in upper and lower extremity transplantation, where gender mismatched pairs are accepted (5,6). Minor concerns over disparities in skin texture and adnexae (i.e. facial hair) in the male-to-female face transplant scenario could be addressed post-operatively with electrolysis/laser hair removal. Contour discrepancies related to morphologic differences in skeletal form between men and women could be addressed with bone grafting, alloplastic augmentation, facial skeletal osteotomies, or soft tissue camouflage procedures. In addition, the hormonal mileu (ie. circulating testosterone) of the male recipient receiving a female facial alloflap (and vice versa) may dictate secondary skin/hair characteristics of the vascularized composite alloflap, negating the need for postoperative refinements – as previously described in upper and lower extremity transplant scenarios (5,6).

The aim of the current study is to investigate facial skeletal harmony and phenotype compatibility following mock cadaveric cross-gender double-jaw, Le Fort-based craniomaxillofacial transplantation. We present a cadaveric study for both possible scenarios including female-to-male and male-to-female. Emphasis is placed on photograph analysis and hybrid skeletal relationships. Custom cutting guides, by way of three-dimensional cephalometric imaging, were employed in order to optimize post-transplant skeletal relation. Virtual planning was utilized and developed by way of experiences learned in our large animal experimental studies. Our laboratory has, to date, conducted three cadaveric transplants and two live swine Le Fort-based facial transplants, each of which utilized virtual planning and cutting guides analogous to those described here. Lessons learned from these animal surgeries have been invaluable to our team’s progression and has greatly assisted in coordination of resources at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (Laurel, MD) and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, MD).

METHODS

Study Design and Cadaver Procurement

A total of four fresh cadaveric heads, two female and two male, were used in this experimental study to investigate two separate scenarios. Selection of female and male donors versus recipients was based on order of possession (Figure 1A, B). Each dissection was carried out with a consistent double-jaw, Le Fort III-based design, with equivalent recipient defects created bluntly with a ronjeur and drill to mimic trauma-related defects indicative of transplant candidacy. Bilateral neurovascular pedicles were dissected completely but not repaired in entirety given the objective of this study. Of note, each cadaver was donated for the sole purpose of medical research and all specimens were obtained, dissected, and managed in accordance with the institutional review board guidelines of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

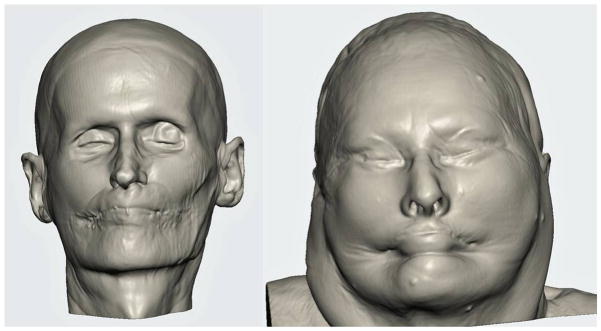

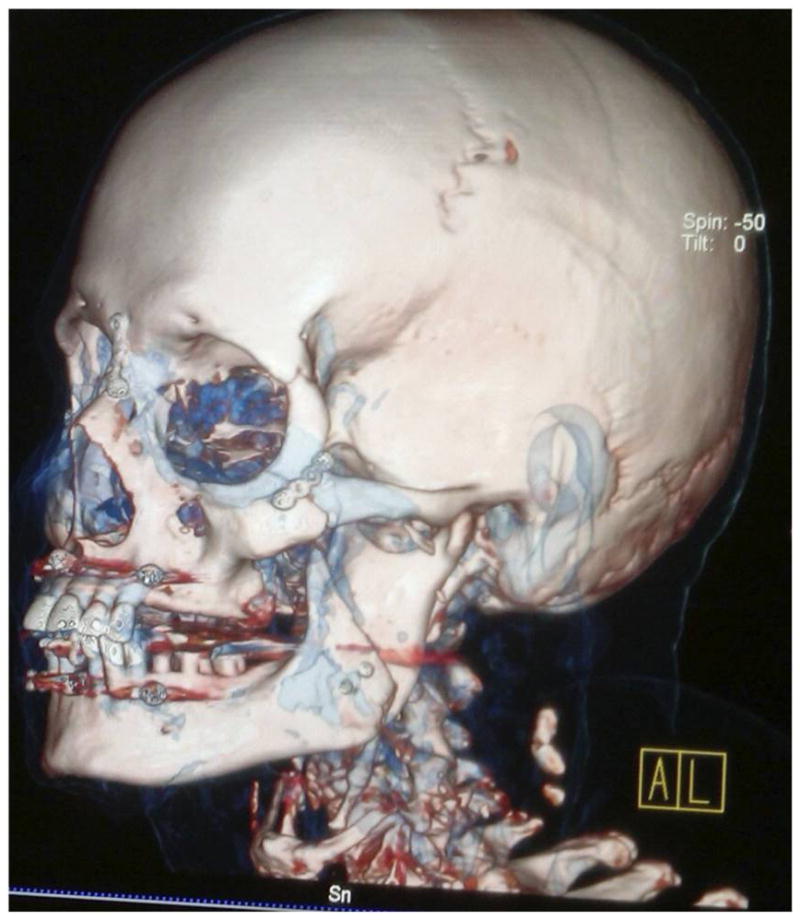

Figure 1.

3D soft tissue reconstructions used in T2MF scenario.

Virtual Surgical Planning and Execution

In 2011, our laboratory began developing a pre-clinical, large animal model for the translational investigation of Le Fort-based, craniomaxillofacial allotransplantation in an effort to improve outcomes related to skeletal and aesthetic harmony. For this study, we performed Le Fort III-based facial transplant dissections. This allowed our team the opportunity to employ numerous modifications and to identify relevant obstacles related to limited exposure and muscle dissections during live surgery, especially since the skeletons are quite similar to humans. As such, the swine’s anatomy lends itself well for innovations related to computer-assisted technology for facial transplantation (7).

For virtual surgical planning, we first perform segmentation and 3D reconstruction of the recipient and donor CT scans (Mimics 15.01, Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Virtual osteotomies are then performed within the software to optimize the donor/recipient match and patient-customized cutting guides templates are created (3-matic 7.01, Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). These templates are then rapid prototyped via either a stereolithography or fused deposition modeling process.

Recipient Preparation

Massive, central orbito-zygomaticomaxillary and mandibular defects spanning from angle-to-angle were created bilaterally in both the female and male recipients (n=2 transplants), to simulate identical clinical scenarios where autologous methods would be inadequate for reconstruction. Defects included destruction and removal of bilateral orbital floors, nasal bones, maxillae, zygomatic complexes, mandibular symphyses, parasymphyses and bodies, partial soft and complete hard palate. All overlying soft tissue including nose, upper and lower lips, and bilateral cheeks was excised en bloc. Of note, the pterygo-masseteric sling was not dissected and left intact, preserving native recipient masticatory function. As the mandible receives partial blood supply from the pterygo-maseteric sling, this is an important technical point because the inferior alveolar artery is divided when executing the sagittal split osteotomy resection for recipient preparation. In addition, the inferior alveolar nerve was identified and preserved for ultimate neurorrhaphy.

Donor Alloflap Harvest

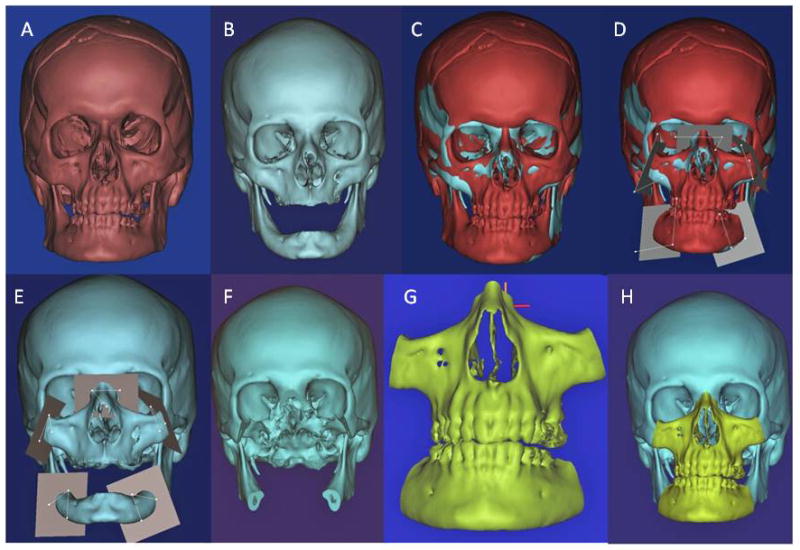

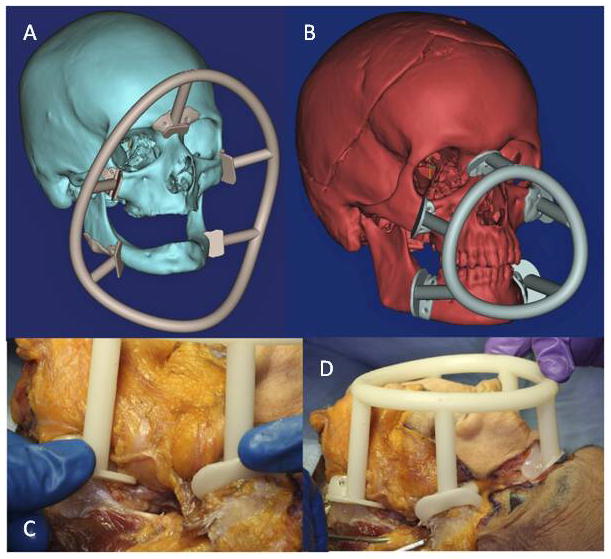

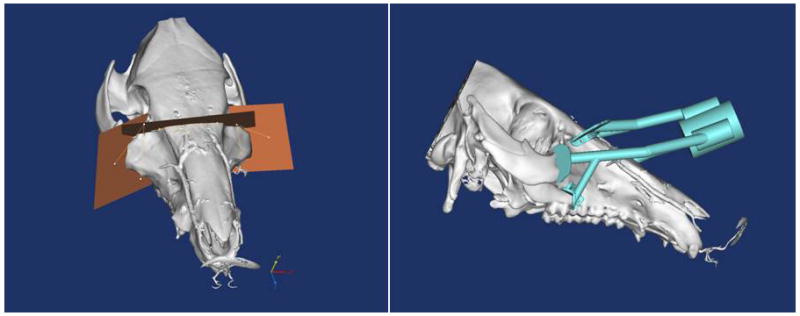

For the female and male donor heads (n=2), double-jaw, Le Fort III-based alloflaps were harvested using handheld osteotomes, a reciprocating saw, and a fine vibrating reciprocating saw. Both osteocutaneous alloflaps were harvested using a double-jaw, Le Fort III-based design (a craniofacial disjunction), with preservation of the pterygoid plates, incorporating all of the midfacial skeleton, complete anterior mandible with dentition, and overlying soft tissue components necessary for ideal reconstruction. Prior to transplantation, both scenarios were completed virtually given the gender-specific challenges to allow custom guide fabrication (Figures 2A–H). Once assimilated, the donor orthognathic two-jaw units were placed into external maxilla-mandibular fixation (MMF) using screw-fixated cutting guides to retain occlusal relationships during the mock transplants (Figure 3A–D).

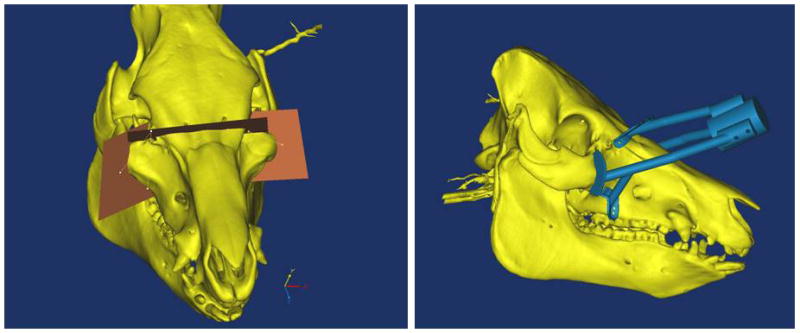

Figure 2.

Figures 2A–H. Virtual surgical planning in preparation for transgender facial transplantation.

Figure 3.

Figures 3A–D. Concentric intraoperative cutting guides, showing virtual planning of both recipient (large circle) (A) and donor (small circle) (B), and pretransplant fixation of the small circle on the donor (C and D).

Transplantation Protocols

Two separate gender-mismatched allotransplants were successfully completed, with the first being a female donor-to-male recipient transplant (T1FM), and the second a male donor-to-female recipient transplant (T2MF). Both transplants were essentially identical, harvesting a Le Fort III-based craniomaxillofacial unit (using a technique previously published by the senior author, including extended zygomatic arches and orbital floors to provide a surplus of osseous support) with bilateral mandibular bodies, and all overlying soft tissue. The osteocutaneous alloflaps were transplanted in MMF to retain donor occlusion, which obviated the need for dental cast models and occlusal splint fabrication previously used by Gordon and colleagues in the single-jaw transplant scenario (8,9).

Rigid fixation was applied (in order of execution) to the following areas: nasofrontal, zygomaticofrontal, zygomaticotemporal, zygomaticomaxillary, and mandibular angles (Stryker CMF, Kalamazoo, MI). Soft tissue was closed in usual layered fashion. Once transplantation was complete, MMF was removed and post-transplant maxillofacial CT scans were obtained, including frontal and lateral cephalograms, thin axial slices with sagittal and coronal reformations, and three-dimensional reconstruction.

Cephalometric Analysis

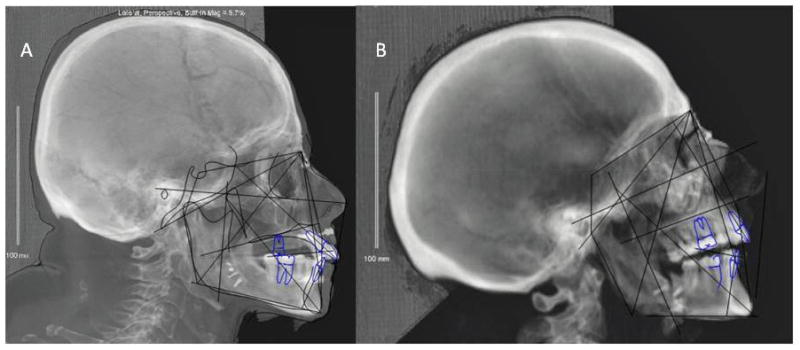

Cephalometric analyses (Dolphin 3D, Dolphin Imaging, Chatsworth, CA) were completed for both post-transplant, gender-mismatched, hybrid skeletons (Figures 4A, B). Emphasis was placed on facial skeletal projection, and facial height and width proportions. However, both donors were transplanted in MMF, and the donor’s skeletal relation/occlusion was retained in both scenarios using a double-jaw technique, as expected (10). Measurements included sellion-nasion-A point (SNA) angle, sellion-nasion-B point (SNB) angle, and lower anterior facial height-to-total anterior facial height ratio (LAFH/TAFH) (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Figure 4A–B. Post-transplantation cephalometric tracings of T1FM (A) and T2MF (B)

Table 1.

Hybrid skeletal relationships from mock cadaveric double-jaw Le Fort-based face transplants.

| SNA ° (SD) | SNB ° (SD) | LAFH/TAFH % (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastman Normal Values | 81 (3) | 79 (3) | 55 (2) |

| Transplant 1: Female to Male (T1FM) | 88 | 84 | 54 |

| Transplant 2: Male to Female (T2MF) | 81 | 73 | 55 |

RESULTS

Both cross-gender cadaveric double-jaw, Le Fort III-based allotransplants were successful in achieving acceptable skeletal harmony and appearance consistent with previously reported gender-matched facial transplants (Figure 5). Operative times of 5.5 and 6.5 hours were equivalent to previously performed cadaveric facial transplantations (8,9). Of note, transplantation of the donor maxilla and mandible en-bloc with pre-surgically designed cutting guides and extraoral MMF resulted in a mean reduced operative time of 4.5 hours compared to previously published cadaveric transplantations by Gordon et al. of maxilla alone, which required dental casts and orthognathic splints to improve hybrid occlusion (8,9).

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of final skeletal harmony in T1FM shown with rigid fixation.

Additional time was required for pre-surgical computer predictions to establish virtual cutting planes on the recipient for skeletal arrangement optimization [average time=25 mins/transplant] and to fabricate computer manufactured (stereolithography) intra-operative cutting guide/maxillomandibular fixation [average time=4 hours/transplant]. Development of the guides was enhanced by having a simultaneous large animal translational model involving swine to practice with and for guide modification based on surgeon feedback (Figures 6A–E).

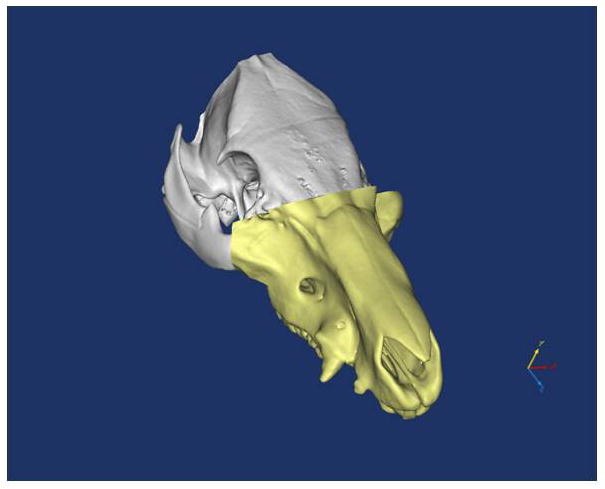

Figure 6.

Figure 6A–E. Images from translational swine surgery depicting (A) pre-operative virtual planning and cutting guide images on larger donor skeleton for Le Fort-III based facial transplantation, (B) pre-operative virtual planning and cutting guide images on smaller recipient skeleton, (C) predicted “hybrid” transplant result, (D) incision design in donor for transplant, and (E) final cutting guide position with dissected osteocutaneous maxillofacial alloflap.

In the first mock transplant scenario (i.e. T1FM), the male recipient retained class I occlusion from the female donor as expected. The sagittal position of the female maxillomandibular unit was slightly prognathic relative to the male cranial base with sellion-nasion-A point (SNA) and sellion-nasion-B point (SNB) angles of 88° and 84°, respectively [Eastman Normal Values: SNA=81±3°, SNB=79±3°]. Facial height proportions were retained with a LAFH/TAFH of 54% [Eastman Normal Value: LAFH/TAFH=55±2%] (Table 1).

For the second transplant, the male maxilla achieved proper positioning relative to the female cranial base with a SNA angle of 81°. The male mandible was slightly retrognathic relative to the female cranial base at a SNB angle of 73°. Again, anterior facial height proportions were retained with a LAFH/TAFH ratio of 54% as expected.

DISCUSSION

Facial transplantation is rapidly establishing itself as the ideal method for reconstructing massive soft and hard tissue defects stemming from various etiologies including close-range ballistic, thermal, electrical, and/or trauma-related events. Recipients not only benefit from a restored appearance for re-integration into society, but also gain vital functions, including valuable sphincter closure (ie. orbicularis oris and oculi), sense of smell with re-establishment of nasal cavity, taste, facial sensation and movement for expression, eyelid function with globe protection and vision preservation, and oral competence for mastication.

To date, all clinical and experimental facial transplantations described in the literature have been between gender-matched donor-recipient pairs. Our study, for the first time, demonstrates that cross-gender facial transplantation can be accomplished with acceptable hybrid skeletal harmony.

In 1994, Farkas defined normative anthropometric values for a wide range of ethnic groups, including both genders (11,12). His work demonstrates that the male craniofacial skeleton has both increased height and width. Yet, skeletal harmony is determined by the relative position and balance of the parts, not by absolute numbers. Moreover, facial height proportions and cranial base-to-facial skeleton angles are largely retained between genders (11). This knowledge may raise concerns that transgender facial transplants would result in a disproportioned hybrid skeleton, as the maxilla-mandibular unit from one gender might not suit the cranial base of the opposite. However, our study exhibits that overall skeletal harmony can be retained following gender-mismatched transplantation by employing prefabricated cutting guides and three-dimensional cephalometric analyses. In fact, we believe expanding the donor pool to include transgender donors will further allow for appropriate size matching in order to achieve correct facial proportions and angles, and assist in minimizing prolonged wait list times complicated by rare blood type and/or viral seropositive-seronegative matching.

For example, a small male recipient, with pre-injury facial height and width on the lower end of normal for males, would be matched to a suitable donor more expeditiously when females are included, who on average would have similar facial height and width, yielding appropriate proportions. This would be similar to situations already described in upper extremity and lower extremity VCA (5,6). In addition, the cadavers used in our study were selected based on order of possession, and satisfactory facial proportions were still achieved with the use of computer generated virtual surgical evaluation and two-team planning. In contrast, transgender facial transplantation would only be undertaken clinically if the donor-recipient pair was ideally size matched, greatly improving outcomes compared to our experimental cadaver study.

The use of advanced computer planning and execution technology offers an enhanced ability to achieve precise outcomes and identify when a donor is a poor match for the recipient. We were able to obtain excellent donor to recipient harmony even across genders by utilizing virtual surgical planning. Having a translational model in swine is also valuable for simultaneous innovation. Furthermore, the use of the virtual environment allows extensive experimentation to find the optimal alloflap design and inset to produce the best result. Importantly, potential concerns that some cross-gender pairs would be too disharmonious – e.g., a male might have a small enough face but highly masculine shape to the mandible that would create a poor aesthetic result – are mitigated by the fact that a donor recipient pair yielding a poor result is readily identified in the computer planning phase before a commitment to transplantation is made.

As the facial transplantation pool of potential donors and recipients begins to increase, the ability of imaging analysis software (e.g., the Dolphin 3D package) to quantitate and store important cephalometric values offers exciting potential. Once hard factors such as immunologic compatibility have been matched, the remaining potential recipients can be identified and ranked based on their degree of anthropometric similarity. A key aspect of this work lies in providing data to support development of such algorithms, which we believe should emphasize similar skeletal structures over factors such as gender.

Skin texture and adnexae disparities, especially facial hair, create a second point of reluctance to include gender-mismatched donors for craniomaxillofacial transplantation. Interestingly, a female-to-male bilateral lower extremity vascularized composite allotransplant case was recently presented at a national meeting (6). It was reported and demonstrated that the transplanted female lower extremity grew similar hair to that of the recipient’s legs in context of the male hormonal mileu. Also, there was no report of psychological inhibition by either the recipient and/or donor family. Such outcomes have also been anecdotally reported in transgender upper extremity transplantation patients, with the first being performed in Poland (5).

Although not specifically addressed by our study, we believe that concerns over skin texture and adnexae mismatch in transgender female-to-male facial transplantation will be put to rest due to recipient hormonal influences on the alloflap. Furthermore, facial hair mismatch in the reverse scenario could be specifically addressed by laser hair removal and/or makeup if there were small discrepancies despite the influence of recipient hormones (ie. circulating estrogen and lack of testosterone). Although this will be more challenging, as many facial transplant recipients undergo revisional surgery, these patients could very well undergo skeletal manipulation with alloplastic augmentation and/or skeletal reduction (i.e. forehead, maxilla, or mandible), if necessary for correcting improper feminization and/or masculinization.

Interestingly, earlier graft loss in donor-recipient gender mismatched pairs is well documented in solid organ transplantation (13). Male recipients of female kidneys have worse short-term and long-term graft survival compared to male-to-male pairs and female recipients of donors of either gender. Causes of these survival discrepancies are largely unknown, and explanations include nephron underdosing (i.e. size mismatch), immunological barriers, hormonal influences on the endothelium, and gender differences in susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion. One study reports worse renal allograft survival in female recipients of male kidneys; postulating that maternal presensitization may play a role (14). Furthermore, there is a higher rate of rejection episodes requiring treatment following female-to-male kidney transplantation, speaking to possible immunological causes of graft failure. Similar results have been seen in heart and liver transplantation, with shorter graft survival in male recipients of female donors (13). However, these results are not uniform and have been contradicted by reports of equivalent outcomes regardless of gender mismatch (15). Also, the rate of rejection episodes requiring treatment in heart and liver transplantation is equivalent across all gender pairings. However, causes of differential allograft survival in solid organ transplantation are not clearly established, which may be of great interest to VCA researchers. Heart, liver, and kidney transplantation must overcome not only immunological barriers, but physiological obstacles as well. Potential immunological barriers between genders need to be taken into consideration, but VCA bypasses issues with differential gender physiology and eliminates the majority of the hypothesized causes of worse allograft survival following gender-mismatched solid organ transplantation. Alloflap survival following upper and lower extremity transgender transplantation serves as a better predictor for transgender craniomaxillofacial allotransplantation as compared to solid organ outcomes.

Limitations to this study include its small sample size and the inability to directly address some of the potential issues raised (i.e. facial hair growth and gender-specific alloflap survival). However, the aim of the investigation was to analyze appearance and facial skeletal harmony following cadaveric transgender facial transplantation in order to address outcome feasibility. This study provides a foundation for further investigation, demonstrating that the building blocks of craniomaxillofacial transplantation, the facial skeleton, are able to achieve proper proportions in gender-mismatched pairs (Figures 7A, B).

Figure 7.

Figure 7AB. Final views of T1FM (A) and T2MF (B).

CONCLUSION

Donor supply is limited for craniomaxillofacial allotransplantation, sometimes requiring candidates to wait numerous years prior to acceptable match. Expanding the donor pool to include gender-mismatched pairs may decrease wait time to reconstruction and allow for skeletal size and viral serology matching. Hybrid facial skeletal harmony can be achieved between gender mismatched pairs. Pre-surgical computer predictions and intra-operative cutting guides aid in achieving desired skeletal proportions. Translational large animal models investigating orthotopic, Le Fort-based, maxillofacial transplantation assist developments in technology. Further investigation is warranted to address the feasibility of transgender facial transplantation in terms of hair growth, psychological impact, and immunological rejection.

Table 2.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Transgender, Le Fort-based Facial Transplantation.

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|

| Increased donor pool (ie. nearly doubling in size) | Skin texture/adnexae mismatch (ie. facial hair) |

| Size-matched donor-recipient pairs (ie. based on buttress height, width, and projection rather than gender) | Gender specific anthropometrics |

| Decreased time on waiting list (ie. may save months to years for some patients) | Potential for increased rate and severity of immunological rejection based on gender mismatch |

| Allows teams to be more selective (ie. CMV Donor/Recipient seronegative matching) | Psychological obstacles |

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the American Society of Maxillofacial Surgery (ASMS 2011 Research Grant), the American Association of Plastic Surgeons (AAPS 2012 Academic Scholar Award), and the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research’s Accelerated Translational Incubator Pilot (ATIP) Program at Johns Hopkins University which is generously supported by the NIH.

Footnotes

Presented at the American Society for Reconstructive Transplantation 3rd Biennial Meeting; November, 2012; Chicago, IL.

Disclosures

None of the authors have conflict of interests, commercial associations or financial disclosures to report for this manuscript.

Outside funding from various grants were used for a portion of this study. This includes grant support by the American Society of Maxillofacial Surgery’s (2011 ASMS Basic Science Research grant), American Association of Plastic Surgeons (2012–14 Furnas’ Academic Scholar Award), and the Accelerated Translational Investigational Program at Johns Hopkins (funded by the National Institute of Health).

This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or endorsement of the Department of the Navy, Army, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Schneeberger S, Gorantla VS, Brandacher G, et al. Upper-extremity transplantation using a cell-based protocol to minimize immunosuppression. Ann Surg. 2013;257(2):345–51. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826d90bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siemionow MZ, Gordon CR. Institutional review board-based recommendations for medical institutions pursuing protocol approval for facial transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1232–1239. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ee482d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon CR, Abouhassan W, Avery RK. What is the true significance of donor-related cytomegalovirus transmission in the setting of facial composite tissue allotransplantation? Transplant Proc. 2011;43:3516–3520. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon CR, Avery RK, Abouhassan W, et al. Cytomegalovirus and other infectious issues related to face transplantation: Specific considerations, lessons learned, and future recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1515–1523. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d03c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jablecki J. World experience after more than a decade of clinical hand transplantation: update on the Polish program. Hand Clin. 2011;27(4):433–42. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavadas PC, Thione A, Carballeira A, Blanes M. Bilateral transfemoral lower extremity transplantation: result at 1 year. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(5):1343–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Štembírek J, Kyllar M, Putnová I, Stehlík L, Buchtová M. The pig as an experimental model for clinical craniofacial research. Lab Anim. 2012;46(4):269–79. doi: 10.1258/la.2012.012062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon CR, Susarla SM, Peacock ZS, et al. Osteocutaneous maxillofacial allotransplantation: Lessons learned from a novel cadaver study applying orthognathic principles and practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:465e–479e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon CR, Susarla SM, Peacock ZS, et al. Le fort-based maxillofacial transplantation: Current state of the art and a refined technique using orthognathic applications. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:81–87. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240ca77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bojovic B, Dorafshar AH, Brown EN, et al. Total face, double jaw, and tongue transplant research procurement: An educational model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:824–834. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262f29c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farkas LG. Anthropometry of the head and face. New York: Raven Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaremchuk MJ. Atlas of facial implants. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeier M, Dohler B, Opelz G, et al. The effect of donor gender on graft survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2570–2576. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000030078.74889.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zukowski M, Kotfis K, Biernawska J, et al. Donor-recipient gender mismatch affects early graft loss after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2914–2916. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdes F, Pita S, Alonso A, et al. The effect of donor gender on renal allograft survival and influence of donor age on posttransplant graft outcome and patient survival. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:3371–3372. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]