Abstract

Objectives

To determine the prevalence and correlates of alcohol dependence disorders in persons receiving treatment for HIV and Tuberculosis (TB) at 16 Primary Health Care centres (PHC) across Zambia.

Methods

649 adult patients receiving treatment for HIV and/or TB at PHCs in Zambia (363 males, 286 females) were recruited between 1st December 2009 and 31st January 2010. Data on socio-demographic variables, clinical disease features (TB and HIV), and psychopathological status were collected. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was used to diagnose alcohol dependence disorder. Correlates of alcohol dependence were analyzed for men only, due to low prevalence in women. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), using general estimating equations to allow for within-PHC clustering.

Results

The prevalence of alcohol dependence was 27.2% (95%CI: 17.7-39.5%) for men and 3.9% (95%CI: 1.4-0.1%) for women. Factors associated with alcohol dependence disorder in men included being single, divorced or widowed compared with married (adjusted OR = 1.47, 95%CI: 1.00-2.14) and being unemployed (adjusted OR=1.30, 95%CI: 1.01-1.67). The highest prevalence of alcohol dependence was among HIV-test unknown TB patients (34.7%), and lowest was among HIV positive patients on treatment but without TB (14.1%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.38).

Conclusions

Male TB/HIV patients in this population have high prevalence of alcohol dependence disorder, and prevalence differs by HIV/TB status. Further work is needed to explore interventions to reduce harmful drinking in this population.

Introduction

Alcohol, HIV and TB are each major contributors to global disease burden and are closely inter-related [1]. Effective intervention strategies are needed within HIV and TB treatment centres that incorporate these inter-relationships at the individual, programmatic, and structural levels. In sub-Saharan Africa, evidence suggests that alcohol impacts on HIV risk with regards to number of partners, transactional sex, violence in relation to sex, condom use, intimate partner violence and drinking environment [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]. Some studies suggest a crude dose response relationship with alcohol consumption and HIV transmission [8].

Cross-sectional and qualitative studies suggest that alcohol relates to increased sexual risk taking behaviors [5,9]. It may be that risk-taking behaviors that influence alcohol use also influence other sexual risk taking, or conversely, those with HIV infection turn to alcohol [5]. However, studies do support a direct relationship between alcohol and HIV incident risk [3,10,11]. This includes a risk not just to the individual using alcohol, but also to a female sexual partner [10]. In some settings, counseling interventions may be effective in reducing this risk [12].

Alcohol use may also affect HIV progression by reducing adherence to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) [13,14]. The direct effect on disease progression on the individual level is more difficult to quantify [15]. Heavy alcohol consumption is related to faster CD4 decline in those not on ART in a US population [16] and those on ART who drink are more likely to have a detectable viral load [17]. In addition, alcohol use may affect the progression of HIV-related illness such as neurocognitive impairment [18].

HIV has exacerbated the TB epidemic, with high co-infection co-morbidity [19,20]. Despite current intervention strategies, TB continues to be a significant contributor to global health burden, prompting calls for research into social determinants and programs that address social factors in TB [21,22]. Alcohol use increases risk for TB, through overlapping risks of social and physical vulnerability, and the ability to adhere to medications [23]. Like HIV, the risk of TB and alcohol is also reflected in gender differences. For men, moderate use of alcohol is not associated with increased risk of TB, but the risk is suggested to increase with heavy drinking [24].

Measures of alcohol use are diverse, which is reflected in the heterogeneity of measurement tools across studies [8,24-27]. Drinking behaviours can be contextually and culturally specific [28]. However, it is useful to differentiate drinking patterns and disorders, as each may be linked to differing outcomes, and understanding of local behaviours will inform the potential effectiveness of interventions.

Alcohol measures aim to differentiate and describe alcohol use to identify unhealthy drinking. Criteria include the quantity of alcohol, the pattern of drinking, and behavioural and physiological consequences. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) differentiates alcohol abuse from dependence, and the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) differentiates harmful drinking from alcohol dependence [29,30]. Although the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and ICD-10 criteria for harmful drinking differ, both reflect recurrent negative consequences of alcohol use over the previous year. Alcohol dependence is defined by a constellation of symptoms and signs including cognitive and physiological, related to a strong desire for a drug [29,31]. The diagnosis for alcohol dependence shows more reliability than harmful drinking or alcohol abuse [31,32]. However, there has been recognition of overlap of diagnostic categories [32]. This is reflected in the DSM-5 which recommends ‘alcohol use disorder ‘ that encompasses abuse and dependence [33].

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was developed to distinguish alcohol use from abuse and dependence by questionnaire, and to be compatible for diagnostic criteria of the ICD-10 [30] and the DSM IV [29]. The MINI has undergone cross-cultural validation [34], and has been used in South Africa for diagnosis and as a validation tool [35,36]. Adaptive processes for local contexts include translation and back translation together with investigation of the aptness of the test for the community [37]. However the MINI has not been validated in the Southern African context to the authors’ knowledge, although the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria, from which the MINI is derived, are used in routine clinical practice in Southern Africa for the diagnosis of mental health disorders.

The aims of this study are to describe and investigate prevalence of alcohol use disorder in men with HIV and/or TB diagnoses in Zambia. The inter-relationships of TB, HIV, alcohol use and gender are clear in Zambia, where the estimated population HIV prevalence is approximately 14.3% and TB prevalence is 421 per 100,000 [38] [39]. HIV prevalence is higher in urban (23.1%) than rural (10%) areas, and is higher in women than men, especially among young people. Among 15-24 year olds, the estimated prevalence is 11.3% for women, and 3.6% for men; this relationship is reversed at older ages (12.1% vs 18.6%) [38].

Alcohol use is recognized as a factor in HIV transmission in the Zambian Government’s 2009 strategy for the prevention of HIV and AIDS [40]. The Demographic and Health Survey of Zambia acknowledges the link between alcohol use and sexual and physical violence towards women: women are more likely to suffer sexual/physical violence if their partner drinks alcohol [41]. Identifying alcohol use patterns and factors associated with harmful drinking in Zambia may facilitate strategies for complementary action in HIV and TB programs.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee and the study was endorsed by the Ministry of Health in Zambia [42]. Written informed consent was obtained from eligible patients prior to participation. At the time of the study, the Zambian ethics committee were informed that the participants for inclusion in this study were 16 years and above and this was approved. A recent Bill enacted by the Zambian Parliament in 2013 has put the age of consent for medical research at 18 years and above [43].

We conducted a cross-sectional survey in 16 primary health care centres (PHCs) [42]. The TB and HIV activities in the PHCs, located in seven districts, were coordinated by the Zambia AIDS Related TB (ZAMBART) Project - a research collaboration between the University of Zambia School of Medicine and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Each PHC is staffed by primary health care physicians and includes an HIV clinic and a TB clinic and acts as the first point of entry into the referral process for the majority of TB and HIV patients.

For this study, inclusion criteria determined that participants were at least 16 years of age, and attended the TB or ART clinics of one of the PHC’s, and had started TB treatment or ART. Due care was taken to avoid recruiting the same participant at the HIV and TB Clinic. Exclusion criteria were medical or psychiatric illness that precluded capacity for consent. Eligible patients were recruited consecutively from the PHC centres from 1st December 2009 to 31st January 2010.

Clinic records confirming HIV and/or TB disease status were required. TB disease was defined to include pulmonary smear positive, pulmonary smear negative or extra-pulmonary TB. All patients suspected of TB were investigated by examination of sputum by microscopy and/or culture. The diagnosis of smear negative or extra-pulmonary TB without laboratory confirmation was made by a health care provider after considering indications as recommended by the World Health Organization [44].

Routine HIV testing is offered to all attendees at the PHCs. Therefore, HIV testing was routinely offered to all newly diagnosed TB patients, and all those presenting to HIV clinics prior to starting ART. Medical records were examined for evidence of the HIV test and result.

Assessment of alcohol dependence and abuse was undertaken as part of a wider study looking at screening tools for mood and mental health disorders in this population [42]. An interviewer administered MINI questionnaire was used to diagnose alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse disorder. This involved a screening question in which the participant recalled alcohol use in the past year, followed by a two-part questionnaire to define alcohol dependence or abuse, respectively. For the purposes of this analysis, the MINI was also used to define current depression. This uses a screening tool based on symptoms of the previous two weeks. If the screen is positive, the patient continues a further questionnaire.

For this study, the MINI was translated into four local languages. Community representatives then back translated, and discrepancies were resolved through an informal committee consensus. Next, translations were piloted and any disagreement was discussed until a final version was agreed upon. Sixteen lay research assistants and 10 mental health care workers were recruited from the study communities and trained on how to obtain informed consent from the participants and on the data collection process.

After informed consent, recruitment and interview took place on the same day. Sociodemographic variables were collected through interviewer-administered questionnaires. Data were double-entered to an Access database.

Statistical methods

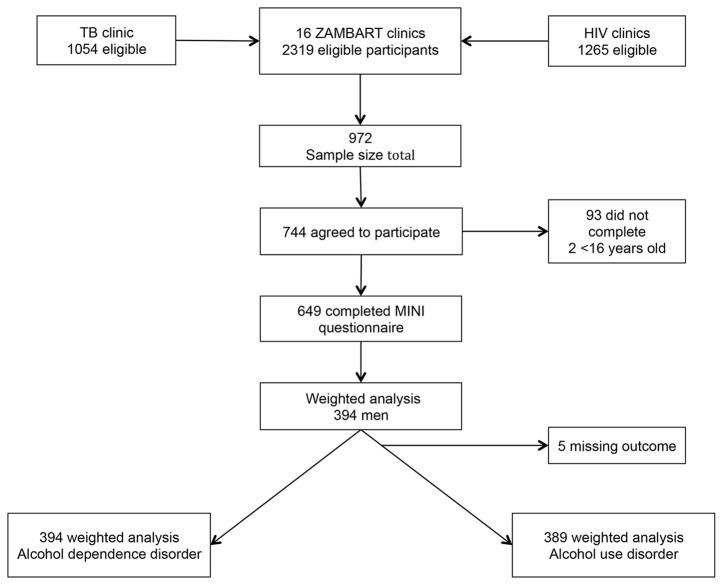

All analysis was performed using STATA 11. The main outcome was alcohol dependence. The three main clinical diagnostic groups included TB disease, TB disease with HIV (TB/HIV positive co-infected), and HIV infection only (no TB disease). Further categorization included a group of participants with TB who had not had an HIV test. Also, TB/HIV positive co-infected patients were considered as to whether they were taking antiretroviral therapy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of clinical categories of participants.

Due to potential within-PHC clustering, STATA survey commands and general estimating equations (GEE) logistic regression were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Participants were not recruited considering probability of selection; therefore post study weighting was performed. We used a pragmatic approach: weighting was designed to take into account the combined size of the TB and HIV clinic in each PHC. Weights created were proportional to the inverse probability of being selected.

For multivariable analysis, a hierarchical approach was used to investigate sociodemographic and clinical factors [45]. Variables considered to have a strong a priori hypothesis for confounding included age, and this was included in all models, together with those with p-value < 0.2 on univariable analysis using the Wald test. Sociodemographic variables were added in order of considered hierarchical importance in proximate and ‘upstream’ influence on the outcome alcohol dependence. After the addition of clinical categories as the first variable in the model as the most proximate factor, intermediate factors were incorporated, including social variables such as marital status and religion. Finally, more distal factors including those reflecting socioeconomic status such as education, employment and rural or urban environment were included. The final model incorporated those variables with evidence for an independent association with alcohol dependence (Wald p value < 0.1), and those with a priori hypothesis and confounders of alcohol dependence and the clinical variables.

Results

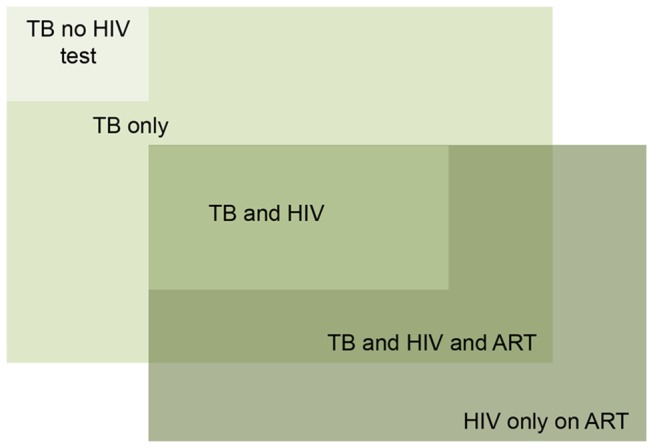

During the study period, 2319 patients attended the TB and/or HIV clinics. Of these, 744 (32.1%) agreed to participate at the screening stage, and 649 (28%) completed the MINI questionnaire (Figure 2). Reasons for not participating were not formally recorded but included: time constraints; confidentiality concerns; and women needing to seek permission from their husbands but not returning to complete the study. There were no reported exclusions due to alcohol intoxication.

Figure 2. Eligibility and participant inclusion.

Among the 649 participants, 394 (60.7%) were men and 255 (39.3%) were women. Of the 394 men, 107 (27.2%) had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence and 20 (5%) a diagnosis of alcohol abuse. Of the 255 women, 10 (3.9%) had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence disorder and 5 (1.9%) a diagnosis of alcohol abuse. Subsequent analyses focus on the 394 males in the study population.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the 394 men are shown in Table 1. The largest PHCs were those in the capital city Lusaka accounting for 62.3% of the men in this study, only 7.9% of the men were from rural PHCs. Unemployment was reported in 175 (44.3%) of the men. Over half (55.3%) were in current marriages, with 28.7% describing themselves as single and 11.4% divorced. The majority had some formal education, with 43.2% attending grade 8 to 12, and 12.6% going to college. Most participants described themselves as members of Christian churches (90.9%), within which there was frequent self-identification with unique, single church Christian organizations.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study male population.

| Variable | Category | N | % (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 394 | 60.7 (52.4,68.5) | |

| Age | 16-29 | 125 | 31.7 (28.4,35.3) |

| 30-34 | 91 | 23.0 (18.9,27.7) | |

| 35-40 | 68 | 17.2 (12.5,23.2) | |

| >40 | 99 | 25.2 (21.6,29.2) | |

| Missing | 11 | 2.8 (2.2,3.7) | |

| Language | English | 33 | 8.2 (3.1,20.1) |

| Tonga | 19 | 4.8 (1.3,18.8) | |

| Bemba | 125 | 31.7 (13.5,57.9) | |

| Lozi | 20 | 5.2 (0.8,27.6) | |

| Nyanja | 197 | 50.0 (24.2,75.9) | |

| Education | No school | 21 | 5.5 (3.1,9.4) |

| Grade 0 to 7 | 145 | 36.7 (31.4,42.4) | |

| Grade 8 to 12 | 171 | 43.2 (37,49.9) | |

| College | 49 | 12.6 (8.9,17.6) | |

| Missing | 8 | 1.9 (0.4,8.2) | |

| Work | Work or other activity | 219 | 55.7 (47.1,63.9) |

| No work | 175 | 44.3 (36.1,52.9) | |

| Marital status | Married | 218 | 55.3 (46.6,63.7) |

| Single | 113 | 28.7 (20.7,38.3) | |

| Divorced | 45 | 11.4 (6.7,18.7) | |

| Widowed | 18 | 4.6 (2.8,7.4) | |

| Religion | Catholic | 94 | 23.9 (18.5,30.4) |

| Protestant | 107 | 27.2 (22.4,32.7) | |

| Muslim | 5 | 1.3 (0.5,3.2) | |

| Seventh Day Adventist | 49 | 12.4 (7.3,20.1) | |

| Jehovah Witness | 30 | 7.7 (4.4,13.3) | |

| Pentecostal/ Evangelical | 73 | 18.6 (13.8,24.6) | |

| No religion | 22 | 5.5 (2.5,11.6) | |

| Other | 12 | 3.0 (1,8.9) | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.5 (0.1,4.0) | |

| Environment 1 | Rural | 31 | 7.9 (2.1,25.9) |

| Urban | 363 | 92.1 (74.1,97.9) | |

| Environment 2 | Provincial | 149 | 37.7 (12.9,71.1) |

| Capital | 245 | 62.3 (28.9,87.1) |

Clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2. Over 90% (355/394) of participants had TB and over half (205/394) were HIV positive. Of those HIV positive, 50.9% were taking ART. Further clarification of clinical diagnosis includes: 16.9% (66/394) had TB but did not have an HIV test result; 31.2% (123/394) had TB and were HIV negative; 9.8% (39/394) had HIV only and were taking ART; 25.5% (101/394) had HIV/ TB co-infection but were not taking ART; 16.6% (65/394) had HIV/TB co-infection and were taking ART.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of the male participants.

| Variable | Category | Weighted male n | Prevalence CI % |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV status | Not tested | 66 | 16.8 (14.3,19.7) |

| Negative | 123 | 31.2 (25.0,38.1) | |

| Positive | 205 | 52.0 (46.6,57.4) | |

| TB status | No TB | 39 | 9.8 (4.1,21.9) |

| TB | 355 | 90.2 (78.1,95.9) | |

| HIV treatment status | No | 101 | 49.1 (39.9,58.4) |

| Yes | 104 | 50.9 (41.6,60.1) | |

| TB retreatment | No | 229 | 64.5 (54.1,73.7) |

| Yes | 120 | 33.8 (23.4,46.1) | |

| Missing | 6 | 1.7 (0.4,6.4) | |

| Clinical diagnosis | HIV test unknown, TB | 66 | 16.9 (14.3,19.7) |

| HIV negative, TB | 123 | 31.2 (25.0,38.1) | |

| HIV/ TB co-infection no ART | 101 | 25.5 (20.6,31.2) | |

| HIV/ TB co-infection on ART | 65 | 16.6 (11.9,22.7) | |

| HIV positive only, no TB | 39 | 9.8 (4.1,21.9) | |

| CD4 | <=200 | 44 | 42.5 (27.0,59.5) |

| (for those on ART) | >200 | 23 | 22.1 (15.2,31.1) |

| Missing | 37 | 35.0 (20.1,54.4) | |

| Alcohol use disorder | No | 262 | 66.4 (54.8,76.3) |

| Yes | 127 | 32.3 (22.4,44.0) | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.3 (0.4,4.7) | |

| Alcohol abuse | No | 369 | 93.6 (89.1,96.3) |

| Yes | 20 | 5.0 (2.2,11.2) | |

| Missing | 5 | 1.4 (0.4,4.7) | |

| Alcohol dependence | No | 287 | 72.8 (60.5,82.3) |

| Yes | 107 | 27.2 (17.7,39.5) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Current depression | Yes | 43 (11) | 11.0 (8.3,14.5) |

On univariable analysis, alcohol dependence was associated with younger age (p-trend=0.01; Table 3). Those who were currently single were more likely to be alcohol dependent than those who were married (OR=1.69; CI: 1.20-2.35). Employment status was associated with alcohol dependence i.e. those not in work were more likely to have alcohol dependence (OR=1.36; 95% CI: 1.11-1.68). Those who identified as Seventh Day Adventists (SDA) had a lower prevalence of alcohol dependence than Roman Catholics (OR=0.46; 95% CI: 0.32-0.66).

Table 3. Univariable analysis: associations of prevalence of alcohol dependence.

| Variable | Category | Alcohol Dependence n/N | Prevalence of Alcohol Dependence % (CI) | OR (CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 107/394 | 27.2 (17.7,39.5) | |||

| Age | 16-29 | 41/125 | 33.0(19.3,50.3) | 1 | ||

| 30-34 | 26/93 | 29.0 (20.7,39.1) | 0.83 (0.50,1.40) | |||

| 35-40 | 14/68 | 21.1 (9.7,40) | 0.62 (0.26,1.48) | |||

| >40 | 23/97 | 22.9 (12.1,39.2) | 0.60 (0.38,0.95) | <0.01 | ||

| Missing | 3/11 | 24.4 (17.7,39.5) | trend | <0.01 | ||

| Education | No school | 7/21 | 33.3 (14.5,59.5) | 1 | ||

| Grade 0 to 7 | 43/145 | 29.8 (15.7,49.2) | 0.92 (0.33,2.60) | |||

| Grade 8 to 12 | 44/171 | 25.7 (17.6,35.9) | 0.77 (0.19,3.09) | |||

| College | 13/50 | 25.6 (11.9,46.7) | 0.70 (0.40,1.21) | 0.23 | ||

| Missing | 1/7 | 6.5 (0.7,40.6) | ||||

| Language | English | 12/33 | 35.7 (11.0,71.3) | 1 | ||

| Tonga | 4/19 | 20.2 (11.4,33.4) | 0.67 (0.15,3.02) | |||

| Bemba | 29/125 | 23.5 (14.8,35.2) | 0.84 (0.13,5.45) | |||

| Lozi | 4/20 | 18.3 (12.7,25.7) | 0.89 (0.17,4.80) | |||

| Nyanja | 59/197 | 29.8 (14.5,51.7) | 1.50 (0.37,6.41) | 0.36 | ||

| Employment | Employed or other occupation | 5/6219 | 25.5 (17,3 6.4) | 1 | ||

| Unemployed | 51/175 | 29.4 (17.7,44.7) | 1.36 (1.11,1.68) | 0.004 | ||

| Marital status | Currently married | 48/218 | 22.0 (14.2,32.6) | 1 | ||

| Single/ divorced/ widowed | 59/176 | 33.7 (21.9,47.9) | 1.69 (1.21,2.35) | 0.002 | ||

| Religion | Catholic | 23/94 | 24.7 (12.3,43.4) | 1 | ||

| Protestant | 28/107 | 26.3 (18.2,36.2) | 1.13 (0.56,2.27) | |||

| SDA | 7/49 | 13.7 (5.1,32.0) | 0.46 (0.32,0.66) | |||

| JW | 12/30 | 39.4 (18.6,64.8) | 1.75 (1.22,2.51) | |||

| Pentecostal/ Evangelical | 22/73 | 30.1 (18.4,45.2) | 1.41 (0.89,2.24) | |||

| No religion | 10/22 | 46.3 (12.6,83.8) | 2.57 (0.88,7.52) | |||

| Other | 5/17 | 31.2 (7.4,72.0) | 1.56 (0.18,13.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Missing | 0/2 | 0 | ||||

| Environment 1 | Rural | 8/31 | 26.8 (19.2,36.1) | 1 | ||

| Urban | 99/363 | 27.3 (17.1,40.6) | 1 (0.49,2.02) | 1 | ||

| Environment 2 | Provincial | 33/149 | 21.9 (14.7,30.5) | 1 | ||

| Capital | 75/245 | 30.5 (16.7,48.9) | 1.80 (0.73,4.44) | 0.2 | ||

| HIV status | Negative | 41/123 | 33.4 (22.7,46.2) | 1 | ||

| Positive | 43/205 | 21.1 (12.1,34.3) | 0.61 (0.34,1.11) | |||

| Not tested | 23/66 | 34.7 (17.5,57.2) | 1.20 (0.70,2.08) | 0.15 | ||

| TB status | No treatment | 6/39 | 14.1 (6.0,29.6) | 1 | ||

| Treatment | 102/355 | 28.7 (18.1,42.2) | 2.31 (0.67,7.97) | 0.18 | ||

| HIV treatment | No | 25/101 | 25.2 (13.8,41.4) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 18/104 | 17.2 (9.0,30.5) | 0.62 (0.33,1.18) | 0.15 | ||

| TB retreatment | No | 63/229 | 27.3 (16.2,42.2) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 36/120 | 29.8 (15.5,49.5) | 1.28 (0.60,2.75) | 0.73 | ||

| Missing | 4/6 | 59.7 (13.7,93.3) | ||||

| Clinical diagnosis | HIV negative, TB | 41/123 | 33.4 (22.7,46.2) | 1 | ||

| HIV test unknown, TB | 23/66 | 34.7 (17.5,57.2) | 1.19 (0.69,2.06) | |||

| HIV/ TB co-infection no HIV treatment | 25/101 | 25.2 (13.8,41.4) | 0.76 (0.42,1.35) | |||

| HIV/ TB co-infection on HIV treatment | 12/65 | 19.1 (8.4,37.5) | 0.53 (0.26,1.10) | |||

| HIV positive only | 5/39 | 14.1 (6.0,29.6) | 0.39 (0.11, 1.26) | 0.33 | ||

| Depression | No | 97/351 | 27.7 (18.0,40.1) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 10/43 | 23.3 (11.1,42.7) | 0.73 (0.38,1.38) | 0.33 | ||

There was a suggestion of difference in alcohol prevalence according to clinical diagnostic category, but univariable analysis did not support statistical differences between patient populations. Alcohol dependence was more prevalent among those with TB compared to those with HIV only (OR=2.31; CI = 0.67–7.97). Among HIV positive patients, alcohol dependence was less common among those on ART than those not on ART (OR=0.62; 95% CI: 0.33-1.18). There was no association between alcohol dependence and being on TB retreatment (OR=1.28; 95% CI: 0.60-2.75).

Multivariable analyses (Table 4) showed that, with TB infection only as reference, those with HIV only on ART were least likely to have alcohol dependence (OR=0.43; 95% CI: 0.15-1.29) followed by those with TB and HIV on ART (OR=0.63; 95% CI: 0.23-.72). However, there was not strong evidence to support a true difference between clinical groups. Religion remained independently associated with alcohol dependence. Other proximate risk factors somewhat associated with alcohol dependence were being single compared with currently married (OR=1.47; 95% CI: 1.00-2.14), and being out of work compared with being employed (OR=1.30; 95% CI: 1.01-1.67).

Table 4. Multivariable analysis: associations of prevalence of alcohol dependence.

| Variable | Category | OR | CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical categories | TB only | 1 | 0.38 | |

| TB HIV unknown | 1.17 | 0.62,2.22 | ||

| TB and HIV no ART | 0.95 | 0.38,2.41 | ||

| TB/ HIV and ART | 0.63 | 0.23,1.72 | ||

| HIV only and ART | 0.43 | 0.15,1.29 | ||

| Age | 16-29 | 1 | 0.78 | |

| 30-34 | 0.97 | 0.45,2.06 | ||

| 35-40 | 0.75 | 0.20,2.78 | ||

| >40 | 0.91 | 0.61,1.34 | ||

| Missing | 0.61 | 0.16,2.34 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 1 | 0.05 | |

| Single, divorced, widowed | 1.47 | 1.00,2.14 | ||

| Employment | Employed or other | 1 | 0.04 | |

| Unemployed or other | 1.30 | 1.01,1.67 | ||

| Religion | Catholic | 1 | <0.01 | |

| Protestant | 1.32 | 0.68,2.57 | ||

| SDA | 0.58 | 0.37,0.89 | ||

| JW | 1.79 | 0.93,3.45 | ||

| Pentecostal/ Evangelical | 1.73 | 1.00,2.99 | ||

| No religion | 2.51 | 1.00,6.27 | ||

| Other | 1.79 | 0.14,23.3 |

Discussion

The prevalence of alcohol dependence disorder was high among men with TB disease and/or HIV (27.2%). Women with TB disease and/or HIV had a low prevalence of alcohol dependence disorder (3.9%). This striking gender difference is in keeping with other study findings of alcohol use in Zambia and other sub Saharan African countries [27,28,46-48]. For example, in a South African study among HIV patients, male alcohol dependence was 22.7%, while female alcohol dependence was 4.7% [49]. In a primary health care setting (non-HIV/TB) in Uganda, the prevalence of alcohol dependence using the DSM diagnostic criteria, was 14.9% for males and 4.9% for females [50]. Although men tend to have a higher prevalence of alcohol use disorders than women, the consequences are also felt by women who are at increased risk of HIV transmission and partner violence [5,51].

There are no general population studies which have used the MINI in Zambia, but in a population survey conducted in 2004 in which alcohol use was self-reported, 9.5% of the men reported as infrequent heavy drinkers, compared with 1.2% of women; and 2.6% of men as frequent heavy drinkers versus 0.5% of women [46]. Although not directly comparable due to different definitions of alcohol use, the prevalence of problem drinking in the general population seems lower than our study population. A study looking at alcohol use in Zambian HIV serodiscordant couples found similar gender disparity [52].

While the prevalence of alcohol dependence is clearly higher in women than men in our study, gender impacted participation in the study and social desirability may impact on willingness to disclose to health care professionals. Some women wished to seek clarification from a partner regarding participation, and then did not return. Also, women may engage in alcohol drinking patterns associated with increased risk behaviour, but not meeting diagnostic criteria for abuse or dependence [53].

In assessing evidence for the relationship between alcohol, HIV and TB, comparison between studies is complicated by heterogeneity of measures of alcohol use [6,9,47]. Further, alcohol use can be culturally and context specific, relating to local and particular consumption patterns, complicating further comparative analysis [54] [55]. The advantage of using DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence in our study, as measured by the MINI, is that it is considered to be more robust and reproducible across cultural contexts than other methods [31].

We also found differing prevalence of alcohol dependence in each clinical HIV/TB category, although this is not statistically significant. The prevalence is lowest in those with HIV only, and highest in those with TB only. As with all cross-sectional studies, limitations prohibit defining causal associations. In other studies investigating TB, the association with chronic heavy alcohol use is clear, and this may be the case in this study. Alternatively, it may be that those who have alcohol use disorder are not offered ART, and/or those starting ART are advised not to drink. In addition, those on ART may change drinking patterns due to the desire to become well with ART.

Alcohol dependence was more prevalent than abuse in this study, as measured by the MINI. Drawing a distinction between the excess chronic harmful alcohol use of alcohol dependence and ‘acute’ harmful alcohol use may be necessary in aiding design of programmes to address alcohol reduction strategies in differing clinical contexts. Different drinking disorders, patterns and contexts may have differing consequences [5,28]. In diagnosing alcohol use disorder using the MINI questionnaire, dependence precludes a diagnosis of abuse. However, studies from the USA suggest the two diagnoses may co-occur: abuse patterns may occur in those with dependence; those with abuse may develop dependence [56,57]. ‘Acute alcohol’ intake may be associated with HIV risk, whereas dependence and long-term use may be associated with deleterious effects on health, increasing susceptibility to TB, and both patterns could impact on adherence.

Social factors associated with alcohol dependence in this study included marital status and occupation status. Those who were not married were more likely to be diagnosed with alcohol dependence, as were those unemployed. In this study, the group with active occupations is heterogeneous, including students and the retired and further differentiation is necessary to clarify associations. Direction of association in both marital status and employment cases is difficult to determine. Comparison with other studies is difficult, as dependence may have different sociodemographic associations than other measures of alcohol use, or alcohol abuse. Suliman et al found such differing social factors associated with differing stages of alcohol intake and alcohol use disorders in looking at individuals’ transitions from any alcohol use to alcohol abuse and dependence [48]. For example, this may in part explain why Kullgren et al found no association with occupation for alcohol dependence using the CAGE and DSM IV criteria [50].

Religion of choice, or not having a religion, appears to be associated with alcohol use disorder. Seventh Day Adventists were least likely to have diagnosis of alcohol use disorder and those with no stated religion had the highest prevalence. Other studies have found adherence to religion to impact on alcohol use, and religious beliefs may influence complete abstention [58]. However, this may also represent lack of willing to disclose alcohol use and under-reporting may occur [59]. The diverse responses and self-identification with independent churches further complicates analysis. Due to these constraints, and small numbers of participants in each religious category, it is difficult to draw further conclusions as to how alcohol use disorder determined in our study could relate to TB and HIV outcomes according to religion in this population.

Despite known associations of alcohol as a risk for TB and a risk to adherence to TB medications, alcohol dependence was not associated with TB retreatment in this analysis. It may be that survival in that group is poor, and they are therefore not represented. In addition, those with alcohol use disorders may not attend health services, and therefore are not included. As this applies to only a few participants, further exploration of any association or this group is beyond the scope of this study.

However, also excluded are those with issues of attendance to care. Retention in all stages of care is an ongoing problem for HIV health care delivery [60]. There are no data on loss to follow up in our cross-sectional survey. Alcohol dependence could be considered as a factor for both these aspects of HIV and TB health care delivery. Routine use of alcohol use measures would be useful in both groups to investigate the impact of alcohol use disorders on health centre attendance and retention in care.

Alcohol use has a clear impact on risk behaviour, on TB and HIV clinical outcomes, and on adherence to treatment. It seems plausible that alcohol impacts on attendance at health centre settings and retention in care. The diversity of alcohol measures is a barrier to interpreting the impact of alcohol on HIV and TB. Therefore, robust culturally validated yet standardized screening tools could assist in identifying harmful behaviour linked to alcohol use, and therefore where interventions could be achieved.

In HIV, there is some evidence from Sub Saharan settings to suggest counselling interventions can impact alcohol-related risk taking behaviour [61], and can encourage alcohol reduction [62]. Randomised controlled trials of interventions in the TB and HIV clinic setting would help ascertain best practice for sustainable alcohol harm reduction interventions for different harmful drinking patterns.

Our study had some methodological limitations. The survey design did not take into account the size of clinic, and therefore the probability of selection of each participant. We minimized selection bias in the analysis using post-hoc weighting. It was not possible to obtain full clinical data for participants.

As discussed, evidence from studies suggests in those with alcohol related disorders there is an association with poorer outcomes in both HIV and TB [13,17,63]. However, in this study it was not possible to comment on severity of illness and alcohol dependence, as this information was not collected. The CD4 count was only measured on those in the ART programme, and so there was insufficient CD4 data to assess whether there was more advanced HIV with alcohol dependence. The clinical type of TB, and severity of TB illness was not available.

To conclude, alcohol dependence is highly prevalent in this population, especially among males, but interventions for alcohol disorders are under-investigated in the lower income setting [25]. The TB and HIV population in our study is typical of the TB and HIV patients one would find in PHC settings in Zambia. However, our findings on alcohol dependence may not be generalisable to the Zambian population, nor to TB/HIV patients seeking treatment in other PHCs. The survey results contain a suggestion that there may be differing prevalence according to whether there is TB, HIV and/or ART and this may represent real different alcohol use patterns. If the differing prevalences are representative, this suggests incorporating alcohol use screening into HIV/TB programs may help identify those at risk and interventions could be targeted according to clinical need, and complement existing TB and HIV programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support rendered by the Zambian Ministry of health in allowing us to conduct the study at their 16 PHCs. We would also like to thank the mental health staff at the PHCs and research assistants for their help with data collection.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by the Evidence for Action on HIV treatment and care systems (EfA) research consortium. EfA is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. WHO (2008) Global Burden of Disease. Update 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woolf-King SE, Maisto SA (2011) Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Arch Sex Behav 40: 17-42. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9516-4. PubMed: 19705274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baliunas D, Rehm J, Irving H, Shuper P (2010) Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 55: 159-166. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-0095-x. PubMed: 19949966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Irving H, Rehm J (2009) Alcohol as a correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS: review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav 13: 1021-1036. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. PubMed: 19618261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chersich MF, Rees HV (2010) Causal links between binge drinking patterns, unsafe sex and HIV in South Africa: its time to intervene. Int J STD AIDS 21: 2-7. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2000.009432. PubMed: 20029060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S (2007) Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci 8: 141-151. doi:10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. PubMed: 17265194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pithey A, Parry C (2009) Descriptive systematic review of sub-Saharan African studies on the association between alcohol use and HIV infection. Sahara J-Journal of Social Aspects of Hiv-Aids 6: 155-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH (2007) The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sex Transm Dis 34: 856-863. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318067b4fd. PubMed: 18049422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shuper PA, Neuman M, Kanteres F, Baliunas D, Joharchi N et al. (2010) Causal considerations on alcohol and HIV/AIDS--a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol 45: 159-166. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agp091. PubMed: 20061510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mavedzenge SN, Weiss HA, Montgomery ET, Blanchard K, de Bruyn G et al. (2011) Determinants of differential HIV incidence among women in three southern African locations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 58: 89-99. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182254038. PubMed: 21654502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geis S, Maboko L, Saathoff E, Hoffmann O, Geldmacher C et al. (2011) Risk factors for HIV-1 infection in a longitudinal, prospective cohort of adults from the Mbeya Region, Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 56: 453-459. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182118fa3. PubMed: 21297483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kalichman SC, Cain D, Eaton L, Jooste S, Simbayi LC (2011) Randomized clinical trial of brief risk reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Am J Public Health 101: e9-e17. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300236. PubMed: 21778486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL (2010) A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Bashi J, Aboubakrine M, Messou E et al. (2010) Alcohol use and non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients in West Africa. Addiction 105: 1416-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02978.x. PubMed: 20528816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hahn JA, Samet JH (2010) Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 7: 226-233. doi:10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. PubMed: 20814765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Samet JH, Cheng DM, Libman H, Nunes DP, Alperen JK et al. (2007) Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 46: 194-199. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318142aabb. PubMed: 17667330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu ES, Metzger DS, Lynch KG, Douglas SD (2011) Association between Alcohol Use and HIV Viral Load. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 56: e129-e130. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820dc1c8. PubMed: 21532918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joska JA, Fincham DS, Stein DJ, Paul RH, Seedat S (2010) Clinical correlates of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in South Africa. AIDS Behav 14: 371-378. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9538-x. PubMed: 19326205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harries AD, Zachariah R, Corbett EL, Lawn SD, Santos-Filho ET et al. (2010) The HIV-associated tuberculosis epidemic? when will we act? Lancet 375: 1906-1919. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60409-6. PubMed: 20488516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lawn SD, Harries AD, Williams BG, Chaisson RE, Losina E et al. (2011) Antiretroviral therapy and the control of HIV-associated tuberculosis. Will ART do it? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Against Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 571-581. doi:10.5588/ijtld.10.0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawn SD, Zumla AI (2011) Tuberculosis. Lancet 378: 57-72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3. PubMed: 21420161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Dye C, Raviglione M (2009) Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med 68: 2240-2246. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. PubMed: 19394122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Neuman MG, Room R, Parry C et al. (2009) The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health 9: 450. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-450. PubMed: 19961618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lönnroth K, Williams BG, Stadlin S, Jaramillo E, Dye C (2008) Alcohol use as a risk factor for tuberculosis - a systematic review. BMC Public Health 8: 289. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-289. PubMed: 18702821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A et al. (2007) Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370: 991-1005. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. PubMed: 17804058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luchters S, Geibel S, Syengo M, Lango D, King et al. (2011) Use of AUDIT, and measures of drinking frequency and patterns to detect associations between alcohol and sexual behaviour in male sex workers in Kenya. BMC Public Health 11: 384. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-384. PubMed: 21609499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel V (2007) Alcohol Use and Mental Health in Developing Countries. Ann Epidemiol 17: S87-S92. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.019. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clausen T, Rossow I, Naidoo N, Kowal P (2009) Diverse alcohol drinking patterns in 20 African countries. Addiction 104: 1147-1154. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02559.x. PubMed: 19426287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. APA (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR.

- 30. WHO (2007) International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schuckit MA (2009) Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 373: 492-501. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X. PubMed: 19168210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li TK, Hewitt BG, Grant BF (2007) The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome, 30 years later: a commentary. the 2006 H. David Archibald lecture. Addiction 102: 1522-1530. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01911.x. PubMed: 17680851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. APA (2013) iagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J et al. (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59 Suppl 20: 22-33;quiz 34-57 PubMed: 9881538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Myer L, Smit J, Roux LL, Parker S, Stein DJ et al. (2008) Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDs 22: 147-158. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0102. PubMed: 18260806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spies G, Kader K, Kidd M, Smit J, Myer L et al. (2009) Validity of the K-10 in detecting DSM-IV-defined depression and anxiety disorders among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Care 21: 1163-1168. doi:10.1080/09540120902729965. PubMed: 20024776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smit J, van den Berg CE, Bekker LG, Seedat S, Stein DJ (2006) Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of a mental health battery in an African setting. Afr Health Sci 6: 215-222. PubMed: 17604510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. UNAIDS (2010) UN Country Progress Report Zambia Avaialable: http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2010countries/zambia_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf. Accessed 2013

- 39. WHO (2010) HO Global Tuberculosis Control. [Google Scholar]

- 40. National AIDS Council Z, NAC (2008) ational Strategy for the Prevention of HIV and AIDS in Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- 41. CSO CSOCZaMII (2009) ambia 2007 Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chishinga N, Kinyanda E, Weiss HA, Patel V, Ayles H et al. (2011) Validation of brief screening tools for depressive and alcohol use disorders among TB and HIV patients in primary care in Zambia. BMC Psychiatry 11: 75. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-75. PubMed: 21542929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zambian Government (2013). The National Health Research Act No. 2. Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- 44. WHO (2007) Improving the diagnosis and treatment of smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis among adults and adolescents. Recommendations for HIV-prevalent and resource-onstrained settings.

- 45. Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MT (1997) The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol 26: 224-227. doi:10.1093/ije/26.1.224. PubMed: 9126524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. WHO (2008) World Health Survey: Zambia Report Available: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whsresults/en/index1.html. Accessed 2013.

- 47. Acuda W, Othieno CJ, Obondo A, Crome IB (2011) The epidemiology of addiction in Sub-Saharan Africa: a synthesis of reports, reviews, and original articles. The American journal on addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions 20: 87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Suliman S, Seedat S, Williams DR, Stein DJ (2010) Predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders in South Africa. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 71: 695-703. PubMed: 20731974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Olley BO, Gxamza F, Seedat S, Theron H, Taljaard J et al. (2003) Psychopathology and coping in recently diagnosed HIV/AIDS patients--the role of gender. S Afr Med J 93: 928-931. PubMed: 14750493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kullgren G, Alibusa S, Birabwa-Oketcho H (2009) Problem drinking among patients attending primary healthcare units in Kampala, Uganda. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 12: 52-58. PubMed: 19517048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zablotska IB, Gray RH, Koenig MA, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F et al. (2009) Alcohol use, intimate partner violence, sexual coercion and HIV among women aged 15-24 in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav 13: 225-233. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9333-5. PubMed: 18064556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coldiron ME, Stephenson R, Chomba E, Vwalika C, Karita E et al. (2008) The relationship between alcohol consumption and unprotected sex among known HIV-discordant couples in Rwanda and Zambia. AIDS Behav 12: 594-603. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9304-x. PubMed: 17705032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zablotska IB, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F, Kigozi G et al. (2006) Alcohol use before sex and HIV acquisition: a longitudinal study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS 20: 1191-1196. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000226960.25589.72. PubMed: 16691071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pithey A, Parry C (2009) Descriptive systematic review of sub-Saharan African studies on the association between alcohol use and HIV infection. Sahara J 6: 155-169. doi:10.1080/17290376.2009.9724944. PubMed: 20485855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Greenfield TK, Nayak MB, Bond J, Patel V, Trocki K et al. (2010) Validating alcohol use measures among male drinkers in Goa: implications for research on alcohol, sexual risk, and HIV in India. AIDS Behav 14 Suppl 1: S84-S93. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9734-8. PubMed: 20567894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hasin DS, Grant BF (2004) The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61: 891-896. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891. PubMed: 15351767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ray LA, Hutchison KE, Leventhal AM, Miranda R Jr., Francione C et al. (2009) Diagnosing alcohol abuse in alcohol dependent individuals: diagnostic and clinical implications. Addict Behav 34: 587-592. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.028. PubMed: 19362427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bernards S, Graham K, Kuendig H, Hettige S, Obot I (2009) 'I have no interest in drinking': a cross-national comparison of reasons why men and women abstain from alcohol use. Addiction 104: 1658-1668. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02667.x. PubMed: 19681798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hahn JA, Bwana MB, Javors MA, Martin JN, Emenyonu NI et al. (2010) Biomarker testing to estimate under-reported heavy alcohol consumption by persons with HIV initiating ART in Uganda. AIDS Behav 14: 1265-1268. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9768-y. PubMed: 20697796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rosen S, Fox MP (2011) Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLOS Med 8: e1001056 PubMed: 21811403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S et al. (2007) HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually transmitted infections clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 44: 594-600. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180415e07. PubMed: 17325606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Papas RK, Sidle JE, Gakinya BN, Baliddawa JB, Martino S et al. (2011) Treatment outcomes of a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral trial to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected out-patients in western Kenya. Addiction 106: 2156-2166. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03518.x. PubMed: 21631622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Greenfield SF, Shields A, Connery HS, Livchits V, Yanov SA et al. (2010) Integrated Management of Physician-delivered Alcohol Care for Tuberculosis Patients: Design and Implementation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34: 317-330. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01094.x. PubMed: 19930235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]