Abstract

Objectives

To differentiate between forms of intimate partner violence (IPV) (victim only, perpetrator only, or participating in reciprocal violence) and examine risk profiles and pregnancy outcomes.

Design

Prospective

Setting

Washington, DC, July 2001 to October 2003

Sample

1044 high-risk African-American pregnant women who participated in a randomized controlled trial to address IPV, depression, smoking, and environmental tobacco smoke exposure.

Methods

Multivariable linear and logistic regression

Main outcome measures

Low and very low birth weight, preterm and very preterm birth

Results

5% of women were victims only, 12% were perpetrators only, 27% participated in reciprocal violence, and 55% reported no IPV. Women reporting reciprocal violence in the past year were more likely to drink, use illicit drugs, and experience environmental tobacco smoke exposure and were less likely to be very happy about their pregnancies. Women reporting any type of IPVwere more likely to be depressed than those reporting no IPV. Women experiencing reciprocal violence reported highest levels of depression. Women who were victims of IPV were more likely to give birth prior prematurely and deliver low and very low birth weight infants.

Conclusions

We conclude that women were at highest risk for pregnancy risk factors when they participated in reciprocal violence and thus might be at higher risk for long-term consequences, but women who were victims of intimate partner violence were more likely to show proximal negative outcomes like preterm birth and low birth weight. Different types of interventions may be needed for these two forms of intimate partner violence.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, pregnancy outcomes, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines intimate partner violence (IPV) as physical, sexual or psychological harm by a current or former spouse or partner,1 with serious psychosocial and physical sequelae. The National Violence against Women Survey found that 22.1% of women and 7.4% of men report any violence by an intimate partner during their lifetimes. Annually, in the U.S approximately 1.3 million women and 835,000 men report physical assault by an intimate partner.2 Using the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System, Breiding and colleagues3 found a lifetime prevalence of IPV was 26.4% in women and 15.9% in men. They also found that the lifetime prevalence of IPV was similar for non-Hispanic African-American and non-Hispanic white women, whereas the rate for the 12-month period preceding the survey was almost twice as high among African-Americans.3

There are a myriad of factors associated with or causally linked to IPV. Women who were younger, had less education and lower income, and those who were single mothers reported more lifetime IPV than their counterparts.4,5 A prevalence study from Canada used data from the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System which questioned women on abuse before, during and after pregnancy. Overall, the prevalence was 10.9% of women reporting abuse during the two years preceding interviews. Women who had low income (21.2% abused), single, divorced, separated or widowed (35.3% abused), < 19 years old (40.7% abused) and Aboriginal mothers (30.6% abused) had a higher prevalence of abuse.6 These findings reinforce those by Bhandari et al. who reported that family stressors such as financial issues, lack of social support, legal and transportation issues put women at increased risk for abuse. 7

There are conflicting reports in the literature about whether pregnancy raises or lowers the risk of intimate partner violence.8,9 Alcohol use has consistently been associated with IPV. A World Health Organization multi-country study found that when one or both partners abused alcohol, there were significantly higher rates of IPV experienced by women.5 Kiely and colleagues10 reported that women with continued IPV during pregnancy were significantly more likely to use alcohol. Breiding et al.11 reported that IPV victimization in women was associated with heavy or binge drinking and cigarette smoking. Illicit drug use has been associated with physical partner violence.12,13 Physical, sexual or psychological IPV have been associated with depressive symptoms.10,14,15 Mistimed or unintended pregnancies were linked to higher rates of IPV in the year before conception or during pregnancy.16 Alcohol,9 tobacco and drug use,17 depression18 and unintended pregnancy9 are not only associated with IPV but are also considered as known risk factors for IPV during pregnancy. Thus, it is important to note if these risk factors are present in women who experience IPV to ensure they receive proper care during pregnancy and post-partum.

IPV increases both pregnancy complications (e.g., inadequate weight gain, maternal infections and bleeding) as well as adverse pregnancy outcomes (low birth weight (LBW), preterm birth (PTB) and neonatal death). 19-21 Kiely et al. report that among women experiencing IPV victimization throughout pregnancy and postpartum, those randomized to the intervention compared to usual care had significantly fewer very preterm births (VPTB) (<33 weeks gestation) and significantly longer mean gestational age at delivery.10 A Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System study found that women reporting IPV in the year before pregnancy were more likely to deliver prematurely and to have LBW infants.22 Other studies have found similar associations between abuse during pregnancy and LBW, PTB, and maternal infections, low gestational weight gain, smoking, alcohol and illicit drug use.19,21,23

While the link between victimization and negative outcomes is established, there may also be an association between women’s aggression and physical and psychological sequelae. Girls who are aggressive in adolescence have higher rates of early pregnancy, have higher rates of obstetric and delivery complications, and score higher for depression and anxiety than their non-aggressive counterparts.24

Partners experience perpetration and victimization differently. The types of violence reported tended to differ, with men reporting more verbal or psychological abuse and women reporting more physical or sexual abuse.25 It has been posited that women react to violence in their relationships, while men initiate it.26 Women are injured more27-29 and have more psychological consequences.3, 15

Few, if any, studies have examined the different ways that pregnant women experience IPV and the risk profiles of each form of IPV (victim, perpetrator or reciprocal). The purpose of this study was to examine the different forms of IPV present in a sample of high-risk pregnant women. We examine the risk factors [alcohol, illicit drug and tobacco use, whether the pregnancy was wanted or not (“pregnancy wantedness”), and depression] by the form of IPV and pregnancy outcome.

METHODS

This study uses data from the National Institutes of Health - District of Columbia Initiative to Reduce Infant Mortality in Minority Populations, a congressionally mandated project to improve maternal and child health outcomes in African-Americans living in the District. The data presented here are from the Healthy Outcomes of Pregnancy Education study, or DC-HOPE, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to address smoking, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETSE), IPV and depression, by providing an integrated behavioral intervention and following the women throughout pregnancy and postpartum. The methods and intervention have been previously described.30

Participants

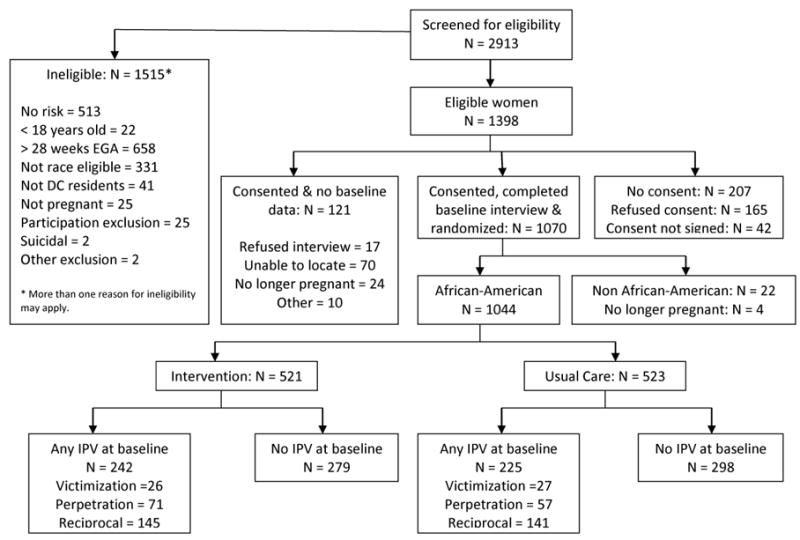

Women were recruited from six prenatal care clinics in DC from July 2001 to October 2003. Women were screened for eligibility in two stages, first based on demographic characteristics (self-identifying as black, African-American or Latina, 18 years old or older, ≤28 weeks gestation, DC resident and English speaking). Those who were demographically eligible were consented and screened by audio-computer assisted self-interview for one of the following risks: smoking, ETSE, IPV, and/or depression. An average of 9 days after screening, they completed the baseline interview and were then consented to participate in the randomized controlled trial. A total of 2,913 women were screened for eligibility. Of those, 1,191 women consented to participate in the study and 1,070 (90%) completed baseline phone interviews and were further randomized into intervention and usual care groups by using site-and risk-specific block randomization. Follow-up data collection by telephone, conducted by interviewers blinded to care group, occurred during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy (22-26 and 34-38 weeks gestation, respectively) and 8-10 weeks postpartum. Data on maternal and infant outcomes were abstracted from medical records. Figure 1 displays the eligibility, consent and randomization process of DC-HOPE. The current analysis includes the 1,044 African-American women who were still pregnant at the time of the baseline questionnaire. These analyses include the data on women in the intervention and control groups.

Figure 1.

Profile of Project DC-HOPE Randomized

Measures

Intimate Partner Violence

IPV was measured by the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale.31 During the baseline interview, women reported IPV they experienced or perpetrated during the previous year. During the follow-up interviews, the period of IPV was since the previous interview. For each item on the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, the women rated the frequency that a particular event happened to them and the frequency with which the women used violence on their partner. Women who reported only being the victim were classified as victims only; women who reported that they used violence on their partner, but their partner did not, were considered perpetrators; and women who were both victims and perpetrators were classified as participating in reciprocal violence. This study used the physical assault and sexual coercion subscales. The minor items on the physical assault subscale include twisting a partner’s arm or hair, pushing or shoving, or grabbing, while the severe items include punching, choking, kicking, or using a knife or a gun with a partner. The sexual coercion scale includes asking about minor items such as insisting on oral, anal or vaginal sex, and more severe items include using force and threats to make a partner have oral, anal or vaginal sex. We report on severe and minor physical IPV, severe and minor sexual IPV, and three different forms of IPV: perpetration, victimization, reciprocal.

Pregnancy Risk Factors

The pregnancy risk factors assessed at baseline and analyzed include alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy, depression, smoking, ETSE, pregnancy wantedness, and pregnancy happiness. These were chosen because previous studies found associations between these factors and negative pregnancy and infant outcomes, such as LBW and PTB.

Alcohol use questions asked about frequency of use during pregnancy of different alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, wine coolers, and liquor). For this analysis, if women reported any type or quantity of drinking during pregnancy, alcohol use was considered to have occurred. Women were coded as using illicit drugs if they reported using marijuana, cocaine, heroin, LSD, amphetamines, sedatives or tranquilizers, or any other drugs since learning they were pregnant (yes/no).

Depression was assessed using the Hopkins Symptom Check List.32 This scale consists of 20 questions asking participants about how they have felt in the past month and whether they were distressed by these symptoms. The symptoms include feeling hopeless about the future, poor appetite, trouble falling asleep, thoughts of death, feeling worthless, and difficulty making decisions. The responses were on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Extremely.” Depression was defined as a mean Hopkins score >0.75.

Smoking at baseline was considered to be present if the participant reported smoking currently or within the last 6 months and verified by salivary cotinine, and had smoked a total of more than 100 cigarettes in her lifetime. ETSE was marked as present if the participants reported being exposed to one or more cigarettes smoked by someone else inside the home or in other places in the past 7 days.

Pregnancy wantedness was determined by participants reporting having an intended pregnancy or one that was not intended currently but wanted eventually. All other women were considered to have an unwanted pregnancy. Finally, happiness about pregnancy was measured by one question that queried participants about the level of their happiness on a scale of 1 to 10. Those who reported happiness levels of 1 to 3 were categorized as unhappy, those who reported happiness of 4 to 7 were categorized as moderately happy, and a report of greater than 7 was considered very happy.

Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes

We measured pregnancy and birth outcomes in the current study. PTB was defined as gestation less than 37 weeks and very preterm birth (VPTB) was defined as gestation less than 34 weeks. Birth weight was measured in grams. LBW was defined as less than 2,500 grams and very low birth weight (VLBW) as less than 1,500 grams at delivery. Finally, small for gestational age (SGA) was based on sex of the infant, birth weight and gestation at delivery. Infants who weighed less than the 10th percentile of weight for gestational age were considered as small for gestational age. These variables were coded as dichotomous for statistical analysis.

Demographic Variables

We used demographic variables previously associated with both IPV and pregnancy outcomes to control the relationships that were tested in the analyses. Maternal education was used as a proxy of socio-economic status and trichotomized as less than high school, high school diploma or GED, and some college. A woman’s relationship status was dichotomized into single (which included divorced, separated, and widowed) or partnered (which included married or having a significant other). We also used maternal age as a continuous control variable in the analyses.

Statistical Analysis

We performed analyses using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In order to examine the associations between different forms of IPV and pregnancy risk factors, we used linear and logistic regression procedures, depending on the type of variable. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated in multivariable logistic regressions for the relationship of interest while controlling for the effects of maternal age, maternal education, and relationship status. Similarly, multivariable linear regressions were estimated with demographic variables and the IPV indicator variables. Finally, happiness to be pregnant is an ordinal variable; therefore, we used multinomial logistic regression.

Similar testing was performed with the pregnancy-related outcomes – all of the outcome variables were dichotomous. Because pregnancy outcomes were determined postpartum and some women were lost to follow-up, only data for the women (n=832) who remained in the study were used in these analyses. We analyzed the baseline data collected for women who did and did not have complete data at follow-up to determine if there were any differences, using ANOVA and Mantel-Haenszel chi-square. Furthermore, since some women received the intervention meant to reduce risky behaviors and exposures, we controlled for care group in the analysis. Finally, we controlled for other risk factors in the fully adjusted models of pregnancy outcomes (preterm birth (PTB), LBW, VLBW, and SGA) if those risk factors showed an association with the outcome at the p ≤ 0.10 level of significance. Therefore, some fully adjusted models include smoking, depression, and alcohol or illicit drug use.

RESULTS

The women ranged in age from 17 to 51, with a mean age of 24.57 years. All of the participants included in these analyses were African-American. At the time of the baseline interview, women were on average 19 weeks pregnant. A large majority of the women were single. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and psycho-behavioral risks at baseline between women who reported any IPV perpetration (n=127), IPV victimization (n=51), reciprocal IPV (n=285) and those who reported no IPV (n=577). Women who reported any IPV at baseline had significantly higher rates of alcohol and illicit drug use, higher depression, and reported more ETSE. Women who dropped out of the study reported higher depression at baseline (mean = 16.48±13.42 for those who remained vs. 19.28±16.18 for those who dropped out, p<0.01) and were more likely to be single (p<0.05) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Select descriptive characteristics of sample at baseline.

| Variables | Women who reported perpetrating IPV (n = 127) Mean ± SD/Percent (n) |

Women who reported being victims of IPV (n = 51) Mean ± SD/Percent (n) |

Women who reported reciprocal IPV (n = 285) Mean ± SD/Percent (n) |

Women who reported no IPV (n = 577) Mean ± SD/Percent (n) |

Difference tests p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 23.94±5.10 | 26.31±6.67 | 24.17±5.27 | 24.74±5.40 | 0.03 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 20.25±6.98 | 18.24±8.80 | 18.92±6.90 | 18.72±6.80 | 0.13 |

| Education: | |||||

| Less than high school | 33.86 (43) | 19.61 (10) | 34.04 (97) | 28.60 (165) | 0.16 |

| High school or GED | 51.97 (66) | 43.14 (22) | 42.81 (122) | 47.49 (274) | |

| Some college | 14.17 (18) | 37.25 (19) | 23.16 (66) | 23.92 (138) | |

| Relationship status: | |||||

| Married/significant other | 28.35 (36) | 23.53 (12) | 24.56 (70) | 22.18 (128) | 0.14 |

| Single/divorced/widowed/separated | 71.65 (91) | 76.47 (29) | 75.44 (215) | 77.82 (449) | |

| Medicaid | 86.51 (109) | 66.00 (33) | 80.99 (230) | 75.83 (436) | 0.04 |

| WIC | 49.21 (62) | 41.18 (21) | 45.26 (129) | 41.59 (240) | 0.13 |

| Currently employed | 31.50 (40) | 35.29 (18) | 37.68 (107) | 37.09 (214) | 0.29 |

| Risk factors: | |||||

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 18.90 (24) | 25.49 (13) | 32.98 (94) | 15.80 (91) | <0.001 |

| Illicit drug use during pregnancy | 12.60 (16) | 11.76 (6) | 17.54 (50) | 8.84 (51) | <0.01 |

| Active smoking | 18.11 (23) | 29.41 (15) | 20.70 (59) | 17.33 (100) | 0.15 |

| ETSE | 76.86 (93) | 66.67 (34) | 80.00 (224) | 68.37 (389) | <0.01 |

| Depression | 17.34 ±13.36 | 19.37±14.19 | 23.16±14.68 | 13.76±12.81 | <0.001 |

| In intervention group | 13.68 (71) | 4.82 (25) | 27.75 (144) | 48.35 (279) | 0.15 |

| Wanted pregnancy | 76.98 (97) | 71.43 (35) | 74.11 (209) | 77.60 (447) | 0.58 |

| Happiness about pregnancy: | |||||

| Unhappy | 14.17 (18) | 31.37 (16) | 22.81 (65) | 18.20 (105) | 0.03 |

| Moderately happy | 44.09 (56) | 33.33 (17) | 42.81 (122) | 38.30 (221) | |

| Very happy | 41.73 (53) | 35.29 (18) | 34.39 (98) | 43.50 (251) |

Note: Differences in means or proportions are denoted by bolded text.

Table 2 displays the adjusted odds ratios for the associations between different IPV forms and other pregnancy risk factors. The no IPV category is the referent group in the analyses. The most consistent finding is that regardless of type of violence (any, minor, severe, physical or sexual) these women are depressed. There is a clear linear trend for increasingly higher levels of depression going from perpetrator only to victim only to reciprocal violence. For women with minor IPV, those participating in reciprocal violence were significantly more likely to use alcohol (OR=2.76, 95% CI=1.95-3.90) and illicit drugs (OR=2.01, 95% CI=1.31-3.07). Women experiencing severe IPV (all forms) were significantly more likely to use alcohol. Women who perpetrate only were significantly more likely to use illicit drugs (OR=1.89, 95% CI=1.02-3.50) as were women who participated in reciprocal violence (OR=3.05, 95% CI=1.83-5.06). For physical IPV, there is a clear linear trend for increasingly significant odds of alcohol use going from perpetrator only (OR=1.63, 95% CI=1.02-2.60) to victim only (OR=2.04, 95% CI=1.00-4.13) to reciprocal (OR=2.89, 95% CI=2.03-4.11). For women reporting sexual IPV, alcohol use was significant for victims (OR=2.17, 95% CI=1.33-3.53) and women participating in reciprocal violence (OR=3.06, 95% CI=1.79-5.23). The women who participate in reciprocal violence were significantly more likely to use illicit drugs (OR=2.11, 95% CI=1.11-4.01).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) associating risk factors of pregnancy and IPV forms

| Risk factors | Perpetrator only | Victim only | Reciprocal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any IPV | |||

| Maternal Age - B (SE) a | -0.80 (0.53) | 1.58 (0.79) | -0.57 (0.39) |

| Relationship status a | 0.72 (0.47, 1.11) | 0.93 (0.47, 1.82) | 0.88 (0.63, 1.22) |

| Maternal Education: a | |||

| Less than high school | 2.00 (1.10, 3.62) | 0.44 (0.20, 0.98) | 1.23 (0.84, 1.81) |

| High school graduate | 1.85 (1.06, 3.23) | 0.58 (0.31, 1.11) | 0.93 (0.65, 1.34) |

| Alcohol use | 1.36 (0.82, 2.26) | 1.63 (0.82, 3.25) | 2.80 (1.99, 3.95) |

| Illicit drug use | 1.43 (0.78, 2.62) | 1.56 (0.63, 3.88) | 2.12 (1.39, 3.25) |

| Smoking | 1.05 (0.62, 1.78) | 2.08 (1.04, 4.15) | 1.27 (0.87, 1.85) |

| ETSE | 1.44 (0.91, 2.29) | 1.02 (0.55, 1.90) | 1.83 (1.30, 2.59) |

| Depression b – B (SE) | 3.93 (1.31) | 5.06 (1.96) | 9.40 (0.97) |

| Pregnancy wantedness | 0.96 (0.60, 1.53) | 0.72 (0.37, 1.40) | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) |

| Pregnancy happiness c: | |||

| Unhappy | 0.72 (0.40, 1.30) | 1.85 (0.89, 3.85) | 1.17 (0.79, 1.71) |

| Very happy | 0.81 (0.53, 1.23) | 0.92 (0.46, 1.8.) | 0.71 (0.51, 0.96) |

| Minor IPV | |||

| Maternal Age - B (SE) a | -0.68 (0.53) | 2.42 (0.79) | -0.63 (0.39) |

| Relationship status a | 0.76 (0.50, 1.17) | 0.93 (0.48, 1.84) | 0.86 (0.62, 1.20) |

| Maternal Education: a | |||

| Less than high school | 1.69 (0.95, 3.01) | 0.43 (0.19, 0.96) | 1.26 (0.85, 1.86) |

| High school graduate | 1.67 (0.97, 2.86) | 0.58 (0.31, 1.12) | 0.97 (0.67, 1.40) |

| Alcohol use | 1.41 (0.85, 2.33) | 1.68 (0.85, 3.31) | 2.76 (1.95, 3.90) |

| Illicit drug use | 1.39 (0.76, 2.55) | 1.23 (0.46, 3.28) | 2.01 (1.31, 3.07) |

| Smoking | 1.06 (0.63, 1.79) | 2.13 (1.07, 4.22) | 1.27 (0.87, 1.85) |

| ETSE | 1.36 (0.86, 2.15) | 1.01 (0.54, 1.87) | 1.75 (1.23, 2.47) |

| Depression b – B (SE) | 3.84 (1.31) | 4.61 (1.96) | 9.57 (0.97) |

| Pregnancy wantedness | 1.02 (0.64, 1.64) | 0.77 (0.39, 1.50) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.15) |

| Pregnancy happiness c: | |||

| Unhappy | 0.81 (0.46, 1.45) | 2.34 (1.12, 4.88) | 1.14 (0.78, 1.69) |

| Very happy | 0.91 (0.60, 1.39) | 1.04 (0.51, 2.13) | 0.71 (0.51, 0.98) |

| Severe IPV | |||

| Maternal Age - B (SE) a | -0.97 (0.60) | 0.22 (0.65) | -0.58 (0.56) |

| Relationship status a | 0.88 (0.53, 1.45) | 1.00 (0.58, 1.74) | 1.02 (0.63, 1.64) |

| Maternal Education: a | |||

| Less than high school | 2.00 (1.02, 3.94) | 0.92 (0.49, 1.72) | 1.47 (0.86, 2.52) |

| High school graduate | 1.74 (0.92, 3.31) | 0.79 (0.45, 1.40) | 0.88 (0.52, 1.50) |

| Alcohol use | 3.05 (1.85, 5.01) | 2.53 (1.49, 4.29) | 4.03 (2.59, 6.27) |

| Illicit drug use | 1.89 (1.02, 3.50) | 1.47 (0.72, 3.01) | 3.05 (1.83, 5.06) |

| Smoking | 1.38 (0.79, 2.43) | 1.05 (0.56, 1.98) | 1.78 (1.10, 2.91) |

| ETSE | 1.99 (1.11, 3.57) | 2.43 (1.28, 4.64) | 1.39 (0.85, 2.27) |

| Depression b – B (SE) | 6.79 (1.51) | 7.87 (1.61) | 9.59 (1.39) |

| Pregnancy wantedness | 0.89 (0.53, 1.50) | 0.98 (0.55, 1.74) | 0.71 (0.45, 1.12) |

| Pregnancy happiness c: | |||

| Unhappy | 0.82 (0.43, 1.57) | 1.76 (0.99, 3.16) | 1.21 (0.72, 2.05) |

| Very happy | 0.85 (0.52, 1.38) | 0.76 (0.43, 1.34) | 0.69 (0.43, 1.11) |

| Physical IPV | |||

| Maternal Age - B (SE) a | -1.05 (0.50) | 1.63 (0.84) | -0.69 (0.40) |

| Relationship status a | 0.67 (0.44, 1.00) | 0.84 (0.42, 1.71) | 0.89 (0.63, 1.27) |

| Maternal Education: a | |||

| Less than high school | 1.68 (0.98, 2.88) | 0.35 (0.14, 0.86) | 1.34 (0.90, 2.00) |

| High school graduate | 1.53 (0.92, 2.52) | 0.59 (0.30, 1.16) | 0.95 (0.65, 1.39) |

| Alcohol use | 1.63 (1.02, 2.60) | 2.04 (1.00, 4.13) | 2.89 (2.03, 4.11) |

| Illicit drug use | 1.24 (0.69, 2.23) | 1.15 (0.39, 3.37) | 2.08 (1.35, 3.19) |

| Smoking | 0.98 (0.59, 1.61) | 1.16 (0.51, 2.63) | 1.26 (0.86, 1.85) |

| ETSE | 1.57 (1.01, 2.45) | 1.81 (0.86, 3.81) | 1.74 (1.21, 2.48) |

| Depression b – B (SE) | 5.18 (1.25) | 7.51 (2.10) | 9.16 (1.01) |

| Pregnancy wantedness | 0.82 (0.53, 1.27) | 1.09 (0.50, 2.36) | 0.76 (0.54, 1.08) |

| Pregnancy happiness c: | |||

| Unhappy | 0.81 (0.48, 1.39) | 1.39 (0.59, 3.25) | 1.23 (0.83, 1.81) |

| Very happy | 0.78 (0.52, 1.16) | 1.25 (0.61, 2.55) | 0.67 (0.48, 0.94) |

| Sexual IPV | |||

| Maternal Age - B (SE) a | -1.38 (0.88) | 1.15 (0.61) | -0.99 (0.69) |

| Relationship status a | 0.92 (0.44, 1.92) | 0.87 (0.53, 1.44) | 2.05 (1.00, 4.21) |

| Maternal Education: a | |||

| Less than high school | 2.42 (0.87, 6.73) | 0.57 (0.33, 1.00) | 1.29 (0.65, 2.58) |

| High school graduate | 1.67 (0.61, 4.57) | 0.39 (0.23, 0.67) | 0.96 (0.50, 1.86) |

| Alcohol use | 1.69 (0.79, 3.60) | 2.17 (1.33, 3.53) | 3.06 (1.79, 5.23) |

| Illicit drug use | 1.99 (0.87, 4.54) | 1.42 (0.73, 2.76) | 2.11 (1.11, 4.01) |

| Smoking | 1.97 (0.92, 4.24) | 1.80 (1.04, 3.10) | 1.94 (1.07, 3.53) |

| ETSE | 1.31 (0.58, 2.93) | 1.25 (0.74, 2.11) | 2.42 (1.16, 5.02) |

| Depression b – B (SE) | 6.91 (2.23) | 7.18 (1.55) | 8.83 (1.73) |

| Pregnancy wantedness | 2.70 (0.94, 7.76) | 0.69 (0.42, 1.16) | 1.19 (0.64, 2.21) |

| Pregnancy happiness c: | |||

| Unhappy | 0.31 (0.07, 1.36) | 1.65 (0.95, 2.86) | 1.14 (0.58, 2.25) |

| Very happy | 1.49 (0.76, 2.94) | 0.77 (0.45, 1.32) | 1.11 (0.63, 1.95) |

Note. The odds ratios are adjusted for maternal age, maternal education, and relationships status

These relationships are bivariate between age, relationship status and maternal education and the different forms of IPV

Depression is a continuous variable; therefore, the coefficients presented are from a linear regression

Moderately happy category is the reference group

Table 3 presents the adjusted odds ratios from the models associating baseline reports of IPV types and forms with pregnancy and infant outcomes (PTB, VPTB, LBW, VLBW, SGA), while controlling for demographic and risk factors. Women who were perpetrators only, were not at significantly increased risk of any of the adverse infant outcomes. Women who reported physical IPV and participated in reciprocal violence were more likely to have a PTB (OR=1.60, 95% CI=1.00-2.57). Women who were victims only were the ones with significantly worse birth outcomes. Victims reporting any type of IPV were more likely to have a LBW infant (OR=2.21, 95% CI=1.04-4.72) or VLBW infant (OR=4.54, 95% CI=1.06-19.44). Victims were more likely to have a VPTB if they reported minor IPV (OR=3.66, 95% CI=1.22-10.97), severe IPV (OR=2.78, 95% CI=1.10-7.06) or physical IPV (OR=3.52, 95% CI=1.06-11.65). Victims reporting physical IPV had significantly more LBW (OR=2.49, 95% CI=1.13-5.52) and VLBW (OR=5.67, 95% CI=1.29-25.02) infants. Victims reporting sexual IPV had significantly more VLBW infants (OR=3.74, 95% CI=1.09-12.85).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) in the model associating pregnancy-related outcomes and IPV forms (any IPV)

| Pregnancy outcomes | Perpetrator only | Victim only | Reciprocal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any IPV | |||

| PTB (< 37 weeks) | 0.74 (0.36, 1.53) | 1.52 (0.68, 3.36) | 1.40 (0.87, 2.23) |

| VPTB (< 34 weeks) | 0.61 (0.13, 2.76) | 2.93 (0.90, 9.54) | 2.06 (0.92, 4.58) |

| LBW (< 2,500 grams) | 0.89 (0.44, 1.72) | 2.21 (1.04, 4.72) | 1.07 (0.49, 1.48) |

| VLBW (< 1,500 grams) | NE a | 4.54 (1.06, 19.44) | 1.72 (0.51, 5.81) |

| SGA | 0.87 (0.49, 1.56) | 1.85 (0.92, 3.72) | 0.62 (0.38, 1.00) |

| Minor IPV | |||

| PTB (< 37 weeks) | 0.89 (0.46, 1.75) | 1.64 (0.76, 3.55) | 1.33 (0.82, 2.15) |

| VPTB (< 34 weeks) | 0.61 (0.13, 2.76) | 3.66 (1.22, 10.97) | 2.01 (0.89, 4.56) |

| LBW (< 2,500 grams) | 1.02 (0.53, 1.94) | 1.83 (0.84, 3.98) | 0.96 (0.57, 1.61) |

| VLBW (< 1,500 grams) | NE a | 4.24 (0.98, 18.30) | 1.87 (0.55, 6.32) |

| SGA | 0.87 (0.49, 1.55) | 1.81 (0.90, 3.63) | 0.59 (0.36, 0.96) |

| Severe IPV | |||

| PTB (< 37 weeks) | 0.75 (0.63, 2.62) | 1.28 (0.75, 2.57) | 1.39 (0.57, 1.26) |

| VPTB (< 34 weeks) | 0.31 (0.04, 2.39) | 2.78 (1.10, 7.06) | 1.13 (0.37, 3.46) |

| LBW (< 2,500 grams) | 0.51 (0.21, 1.25) | 1.66 (0.84, 3.28) | 1.06 (0.54, 2.07) |

| VLBW (< 1,500 grams) | 1.07 (0.13, 8.74) | 3.28 (0.85, 12.65) | 0.81 (0.10, 6.59) |

| SGA | 0.40 (0.17, 0.95) | 0.92 (0.45, 1.89) | 0.88 (0.47, 1.65) |

| Physical IPV | |||

| PTB (< 37 weeks) | 0.74 (0.37, 1.47) | 1.41 (0.58, 3.41) | 1.60 (1.00, 2.57) |

| VPTB (< 34 weeks) | 0.54 (0.12, 2.43) | 3.52 (1.06, 11.65) | 2.15 (0.96, 4.79) |

| LBW (< 2,500 grams) | 0.72 (0.36, 1.45) | 2.49 (1.13, 5.52) | 1.28 (0.77, 2.13) |

| VLBW (< 1,500 grams) | NE a | 5.67 (1.29, 25.02) | 2.06 (0.61, 6.98) |

| SGA | 0.75 (0.43, 1.34) | 1.62 (0.75, 3.48) | 0.65 (0.39, 1.05) |

| Sexual IPV | |||

| PTB (< 37 weeks) | 1.30 (0.52, 3.28) | 1.08 (0.55, 2.13) | 0.98 (0.44, 2.21) |

| VPTB (< 34 weeks) | 0.67 (0.09, 5.25) | 1.57 (0.56, 4.36) | 1.30 (0.36, 4.67) |

| LBW (< 2,500 grams) | 1.21 (0.47, 3.06) | 1.12 (0.55, 2.26) | 0.61 (0.23, 1.62) |

| VLBW (< 1,500 grams) | 2.43 (0.29, 20.54) | 3.74 (1.09, 12.85) | NE a |

| SGA | 0.62 (0.21, 1.81) | 1.32 (0.71, 2.45) | 0.77 (0.33, 1.77) |

Note: The odds ratios are adjusted for maternal age, maternal education, relationship status, care group and baseline risk factors (the latter only if they attained a significant association with the outcome at the p ≤ .01 level)

NE – Not estimated because no women participating in reciprocal violence delivered a VLBW infant.

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

The current study was novel in that we analyzed different forms of IPV – perpetrators, victims, and women participating in reciprocal violence – in a sample targeted specifically at high-risk African-American pregnant women. IPV affects millions of women regardless of economic status, race or ethnicity. The results point to different risk profiles for different kinds of violence. Women who reported reciprocal violence in the past year had higher odds of consuming alcohol and illicit drugs during pregnancy, ETSE exposure, and were the most depressed, which supports and extends findings linked to reciprocal violence in couples.33 Women who reported only victimization in the past year were more likely to smoke and had elevated levels of depression. To our knowledge, few studies have linked various forms of IPV with different types of pregnancy risk.34,35 Although women who reported reciprocal violence had the worst risk profiles, their birth outcomes were similar to women not experiencing IPV. Previous research reported that reciprocal violence being associated with higher injury rates,36 but no one has studied IPV forms as predictors of pregnancy outcomes.

There has been controversy in the literature regarding perpetration, with one side asserting that female perpetration has been ignored37 and the other emphasizing male perpetrators.38 The current study accounts for female perpetration and finds clearly delineated risk profiles for different forms of IPV, especially for victims and reciprocal violence. Women were willing to and did report reciprocal violence, more than victimization only. Previous studies have found that women engaging in violence often do so in the context of responding to partner violence. Swan and Snow39 reported that 75% of women studied stated that their violence was in self-defense. Women also acknowledged fear,40,41 defense of their children,42,43 relationship control,39,40 and retribution, often for being emotionally hurt39, 44 as their motivations for violence. Women experience coercive control, including sexual coercion, while rarely being coercively controlling themselves.40 Future studies should endeavor to gain more insight into the context of IPV during pregnancy.

Studies of IPV generally do not report reciprocal violence because most scales do not ask about perpetration. This may be a reflection that it is not asked simultaneously and researcher’s own biases about the likelihood that women would perpetrate violence. A compendium by the CDC45 reveals that only two scales ask about both victimization and perpetration: the Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale,31 and the Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse.46,47

Alcohol and drug use are often studied in association with IPV, as risk factors or coping mechanisms. Alcohol use has been linked to victimization and perpetration of IPV. Some studies report drinking as a coping mechanism for dealing with IPV,48,49while others posit drinking as a risk factor for victimization,34 and some find that alcohol use was directly related to perpetration.35 Causality is unclear in our study, but the results point to alcohol use as a particular problem for women who participate in reciprocal violence. It is possible that alcohol use could be linked to more aggressive behavior in this group of women; however, there is no way to determine if drinking led to aggressive behavior or if it were used as a coping mechanism. Contrary to current literature, we found that women who were perpetrators only were less likely to acknowledge either alcohol or illicit drug use.50-52 This may be partially explained by the fact that most researchers do not refine perpetration as we did. Our findings suggest providers of services should question women on both perpetration and victimization.

The literature supports our findings that women who experience IPV as victims are more likely to have negative birth outcomes.19,20 However, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to separate the forms of violence and point to victimized women as particularly at risk for LWB and PTB. Previous studies have found that psychosocial stress and stressful life events are linked with LBW specifically in African-Americans.53,54 If IPV increases stress, these episodes may exacerbate the risk of poor pregnancy outcomes. Victims may have been unable to marshal the resourcefulness needed to fight back when abused and may have internalized the stress caused by the abuse. Future studies should include the necessary measures to understand this phenomenon.

Our results emphasize the need to understand how these risk factors interact and act as mediating mechanisms between IPV and pregnancy outcomes.55 during Addressing health behaviors may require a deeper understanding of the temporality and reasons (i.e. coping mechanisms). Likewise, we found that depression during pregnancy was elevated for all forms of IPV and should be addressed in the context of abusive relationships.

Strengths and Limitations

These results should be interpreted in light of study limitations. The sample population is high-risk African-American pregnant women residing in Washington, DC, and thus are not necessarily generalizable a wider population. However, the results inform the kind of elevated risk that affects pregnant women who are already vulnerable. These analyses are longitudinal, involving data collected during pregnancy and including birth outcomes. While there were few differences between women retained and lost to follow-up, the higher depression levels in women who were lost suggest that this group was at higher risk and that our results would have been stronger with complete follow-up The data on risk factors and IPV were self-reported, which may have led to under-reporting due to social desirability. However, the data on pregnancy outcomes were collected through record abstraction, and thus should be considered reliable. The RCT was not originally powered to detect differences in birth outcomes, but rather risk resolution. The original study randomization did not account for different IPV. Future research should include a broader population of pregnant women. Following women longer would facilitate understanding the detrimental effects of different forms of IPV on long-term maternal and child health outcomes.

Interpretation

Despite the limitations, the results provide important insight into differences in the risk profiles of pregnant women experiencing various forms of IPV. We confirm that women who participate in reciprocal violence tend to suffer many negative consequences40 and have serious pregnancy risk profiles. We also add to the literature describing the relationship between IPV and negative birth outcomes, specifically in women who report victimization only. We found clear delineations between forms of violence experienced and risk profiles and outcomes, which may have implications for future research on IPV and clinicians’ practice.

Previous studies reported the benefits of screening for IPV in clinical settings.56,57 Expanding the identification of IPV to include the type and form(s) should be possible within the clinical setting with a similar time investment. This would allow beneficial interventions to alleviate a woman’s behavioral and mental health issues. This knowledge can help providers guide the patient’s pregnancy and birth care decisions. Our results support the recent American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists opinion that screening for IPV should be a routine part of preventive care for women.58 Conclusions: We conclude that women have the most pregnancy risk factors when they are participating in reciprocal violence and thus might be at higher risk for long-term consequences, but women who are victims of IPV are more likely to show proximal negative outcomes like PTB and LBW. When women present for care, their provider should consider perpetration as well as victimization. Different types of interventions may be needed for these two forms of IPV.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge our many collaborators. We would like to thank Dr. John L. Kiely for his scientific and editorial review of the manuscript. We would also like to thank the participants who welcomed us into their lives in hopes of helping themselves and their children.

FUNDING:

This study was supported by grants no. 3U18HD030445; 3U18HD030447; 5U18HD31206; 3U18HD03919; 5U18HD036104, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities

This research was supported, in part, by the intramural program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF INTERESTS

Neither of the authors has any competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTION TO AUTHORSHIP

YS performed the statistical analyses, participated in the interpretation of the results and the writing of the manuscript. YS has given final approval of the manuscript.

MK, as the NICHD Project Officer, oversaw all the activities of the study while it was in the field. She participated in the analysis and interpretation of the results. MK did a significant amount of the original writing of the manuscript, as well as revising it critically for important intellectual content. MK has given final approval of the manuscript.

DETAILS OF ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committees at Howard University (for the clinical sites), RTI International (the data coordinating center) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Copies of the Institutional Review Board approval have been archived and I no longer have access to them. The data were collected as part of a clinical trial, registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00381823

References

- 1.Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements. Version 1.0 Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. 2000. Report No.: NCJ 183781. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Dimer JA, Carrell D, et al. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:447–57. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, Devries K, Kiss L, Ellsberg M, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daoud N, Urquia ML, O'Campo P, Heaman M, Janssen PA, Smylie J, Thiessen K. Prevalence of abuse and violence before, during, and after pregnancy in a national sample of Canadian women. Am J Publi Health. 2012;102:1893–1901. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhandari S, Levitch AH, Ellis KK, Ball K, Everett K, Geden E, Bullock L. Comparative analyses of stressors experienced by rural low-income pregnant women experiencing intimate partner violence and those who are not. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(4):492–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;26(275):1915–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasinski JL. Pregnancy and domestic violence: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2004;5:47–64. doi: 10.1177/1524838003259322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, El-Khorazaty MN, Blake SM, Gantz MG. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:273–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482. (2 Pt 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence-18 U.S. states/territories, 2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:538–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke JG, Thieman LK, Gielen AC, O'Campo P, McDonnell KA. Intimate partner violence, substance use, and HIV among low-income women: taking a closer look. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:1140–61. doi: 10.1177/1077801205276943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Testa M. The role of substance use in male-to-female physical and sexual violence: a brief review and recommendations for future research. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19:1494–505. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina KM, Kiely M. Understanding depressive symptoms among high-risk, pregnant, African-American women. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hien D, Ruglass L. Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: an overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin MM, Gazmararian JA, Johnson CH, Gilbert BC, Saltzman LE. Pregnancy intendedness and physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: findings from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 1996-1997. PRAMS Working Group Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:85–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1009566103493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey BA, Daugherty RA. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: incidence and associated health behaviors in a rural population. Maternal And Child Health Journal. 2007;11(5):495–503. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0191-6. ISSN: 1092-7875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin SL, Li Y, Casanuava C, Harris-britt A, Kupper LL, Cloutier S. Intimate Partner Violence and Women's Depression Before and During Pregnancy. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:221–239. doi: 10.1177/1077801205285106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K. Abuse during pregnancy: associations with maternal health and infant birth weight. Nurs Res. 1996;45:37–42. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah PS, Shah J. Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:2017–31. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boy A, Salihu HM. Intimate partner violence and birth outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2004;49:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: associations with maternal and neonatal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:140–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moraes CL, Amorim AR, Reichenheim ME. Gestational weight gain differentials in the presence of intimate partner violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serbin L, Stack DM, De Genna N, Grunzeweig N, Temmcheff CE, Schwartzman AE, et al. When aggressive girls become mothers. In: Putallaz KL, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior and violence among girls. New York: The Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 262–285. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:260–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West CM, Rose S. Dating Aggression Among Low Income African American Youth: An Examination of Gender Differences and Antagonistic Beliefs. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:470–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:651–80. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: Men's and women's participation and developmental antecedents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;123:258–71. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felson RB, Cares AC. Gender and the seriousness of assaults on intimate partners and other victims. Journal of Marriage and Fam. 2005;67:1182–95. [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Khorazaty MN, Johnson AA, Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, Subramanian S, Laryea HA, et al. Recruitment and retention of low-income minority women in a behavioral intervention to reduce smoking, depression, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. Journal of Fam Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Perpetration of intimate partner aggression by men and women in the Philippines: prevalence and associated factors. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24:1579–90. doi: 10.1177/0886260508323660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:941–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1272–83. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martino SC, Collins RL, Ellickson PL. Cross-lagged relationships between substance use and intimate partner violence among a sample of young adult women. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:139–48. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Straus MA. Why the overwhelming evidence on partner physical violence by women has not been perceived and is often denied. Journal of Aggression. Maltreatment & Trauma. 2009;18:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed E, Raj A, Miller E, Silverman JG. Losing the “gender” in gender-based violence: the missteps of research on dating and intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2010 Mar;16(3):348–54. doi: 10.1177/1077801209361127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swan SC, Snow Dl. Behavioral and psychological differences among abused women who use violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:75–109. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. A review of research on women's use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence Vict. 2008;23(3):301–14. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phelan MB, Hamberger LK, Guse CE, Edwards S, Walczak S, Zosel A. Domestic violence among male and female patients seeking emergency medical services. Violence Vict. 2005;20(2):187–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Browne A. When battered women kill. New York: Free Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morash M, Bui HN, Santiago AM. Cultural-specific gender ideology and wife abuse in Mexican-descent families. International Review of victimology. 2000;7:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kernsmith P. Exerting power or striking back: A gendered comparison of motivations for domestic violence perpetration. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson MP, Basile KC, Hertz MF, Sitterle D. Measuring Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Perpetration: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy CM, Cascardi M. Psychological abuse in marriage and dating relationship. In: Hampton RL, editor. Family Violonce: Prevention and Treatment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 198–226. 2nd. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy CM, Hoover SA. Measuring emotional abuse in dating relationships as a multifactorial construct. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Temple JR, Weston R, Stuart GL, Marshall LL. The longitudinal association between alcohol use and intimate partner violence among ethnically diverse community women. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:102–12. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hines DA, Douglas EM. Alcohol and drug abuse in men who sustain intimate partner violence. Aggress Behav. 2011;37:1–16. doi: 10.1002/ab.20418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ernst AA, Weiss SJ, Enright-Smith S, Hilton E, Byrd EC. Perpetrators of intimate partner violence use significantly more methamphetamine, cocaine, and alcohol than victims: a report by victims. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(5):592–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zahnd E, Aydin M, Grant D, Holtby S. The link between intimate partner violence, substance abuse and mental health in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011 Aug;:1–8. (PB2011-10): [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dominguez TP, Schetter CD, Mancuso R, Rini CM, Hobel C. Stress in African American pregnancies: testing the roles of various stress concepts in prediction of birth outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:12–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2901_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orr ST, James SA, Miller CA, Barakat B, Daikoku N, Pupkin M, et al. Psychosocial stressors and low birthweight in an urban population. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:459–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Machamer P, Darden L, Craver CF. Thinking about mechanisms. Philosophy of Science. 2000;67:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bauer ST, Shadigian EM. Screening for domestic violence. Screening for partner violence makes a difference and saves lives. BMJ. 2002 Dec 14;325(7377):1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shadigian EM, Bauer ST. Screening for partner violence during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;84:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 518. Intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Feb;119:412–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318249ff74. (2 Pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]