Abstract

Many of the pathogens that cause human infectious diseases do not infect rodents or other mammalian species. Small animal models that allow studies of the pathogenesis of these agents and evaluation of drug efficacy are critical for identifying ways to prevent and treat human infectious diseases. Immunodeficient mice engrafted with functional human cells and tissues, termed “humanized” mice, represent a critical pre-clinical bridge for in vivo studies of human pathogens. Recent advances in the development of humanized mice have allowed in vivo studies of multiple human infectious agents providing novel insights into their pathogenesis that is otherwise not possible.

INTRODUCTION

Over 600 million people worldwide are infected with Plasmodium species that cause malaria, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), or hepatitis, accounting for more than 5 million deaths annually (World Health Organization). Mice have provided a platform for investigating many infectious agents leading to insights into the pathogenesis of disease, efficacy of drugs, and evaluation of potential vaccines [1-4]. However, the immune systems of rodents and humans differ greatly [5;6] and a number of infectious agents of most interest do not infect other species [7;8]. Moreover, the recognition of drug-resistant “superbugs”, the threat of bioterrorism, and emerging new infectious agents has accelerated the critical need for small animal models of human infectious diseases.

Since the discovery of the CB17-Prkdcscid (CB17-scid) mouse in 1983 [9], investigators have strived to engraft human cells into immunodeficient mice to develop models for studies of human infectious agents. In 1988, it was reported that human hematopoietic and immune systems could be engrafted in CB17-scid mice [10;11]. These mice supported infection with HIV-1, providing the first animal models of this human-specific viral infection [12;13]. Since 1988, technological and genetic efforts have focused on enhancing human cell engraftment (reviewed in [14]), with a major breakthrough in the early 2000’s describing the development of scid, Rag1null, and Rag2null mice bearing targeted mutations in the gene encoding IL2 receptor common gamma chain (Il2rg, known as γc and CD132) [15-17]. These T and B cell deficient mice lack adaptive immunity, have severe impairments in innate immunity, and completely lack natural killer cells.

Available Strains and Immune Models of Humanized Mice

The most widely available immunodeficient strains for engraftment with human cells and tissues are NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjll (NOD-scid Il2rγnull or NSG) [16;18], NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Sug (NOG) [15], and C.129(cg)-Rag2tm1FwaIl2rgtm1Cgn (BALB/c-Rag2nullIl2rγnull or BRG) mice [17].

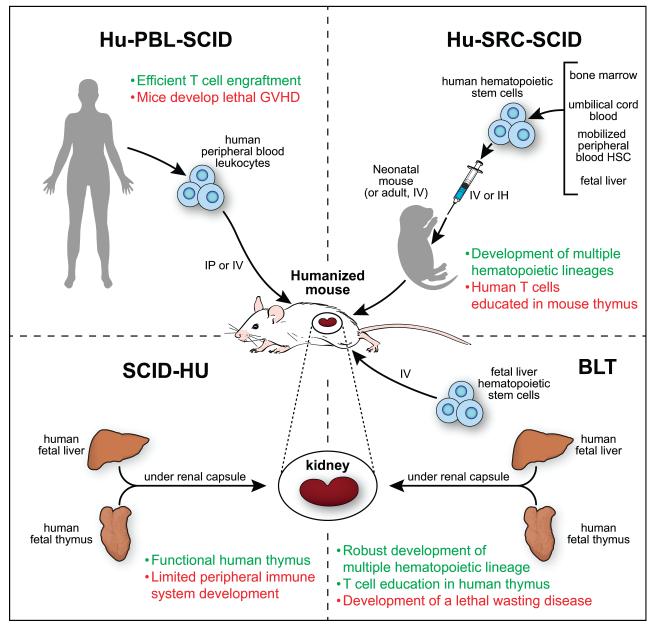

These strains have been engrafted with human hematopoietic and immune cells and tissues to establish four different human immune models, the Hu-PBL-SCID, Hu-SRC-SCID, SCID-Hu and BLT models (Figure 1)( [14;19;20]. As described in Figure 1, each model has advantages and disadvantages that must be considered to select the most appropriate mouse for a specific scientific investigation.

Figure 1. Four major methods of engrafting NSG mice with human hematopoietic cells and tissues.

NSG and other strains of immunodeficient mice have been engrafted with human hematopoietic and immune cells or tissues to establish four different immune system engraftment models Hu-PBL-SCID: This model is established by engraftment of human Peripheral Blood Leukocytes (PBL). Most of the engrafting cells are human T cells that express an activated phenotype while few B cells or myeloid cells engraft. This model, described in 1988 [10], is ideal for the study of agents that infect mature effector T cells such as HIV-1 [67]. One caveat is that these mice will develop a xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease (xeno-GVHD) that results in death, but xeno-GVHD can be delayed using immunodeficient mice lacking mouse MHC class I or class II [68]. Hu-SRC-SCID: This model, termed the Human Stem Repopulating Cell model, is established by engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, fetal liver, or mobilized peripheral blood HSC. Engrafting mature adult immunodeficient IL2rγnull mice with HSC permits the generation of multiple hematopoietic cell lineages but few T cells [69] while human T cells are readily generated following engraftment of newborn or 3-4 week-old NSG and NOG mice with HSC [15;69]. SCID-Hu: This model is established by implantation of human fetal liver and thymus fragments under the renal capsule of immunodeficient mice [14]. Although this was one of the first models available for the study of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), a major limitation is the paucity of human hematopoietic and immune cells in the peripheral tissues. BLT: This model (Bone marrow, Liver, Thymus) is established by implantation of human fetal liver and thymus fragments under the renal capsule of sublethally irradiated immunodeficient mice accompanied by intravenous injection of autologous fetal liver HSC [11]. Use of immunodeficient NOD-scid mice to establish the BLT model led to human immune system engrafted mice [70;71], which is further enhanced by the engraftment of NSG mice [27]. A complete hematopoietic and immune system develops, and the human T cells are educated on a human thymus and are HLA-restricted [19;20]. This model has become the model of choice for studies of many infectious agents due to the robust human immune system and the generation of a human mucosal immune system.

Humanized Mouse Models of Infectious Agents

HIV

Humanized mice have been used to study infectious agents such as HIV-1, that do not infect other species [21;22], with the exception of chimpanzees [23;24]. Although HIV-1 infection of chimpanzees can lead to viremia, the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection in these non-human primates differs in many respects from that of humans [23;24]. Furthermore, use of chimpanzees for biomedical research is banned in Europe and the National Institutes of Health has terminated most research on chimpanzees in the United States and recommended that these non-human primates should be permanently retired to sanctuaries (http://dpcpsi.nih.gov/council/pdf/FNL_Report_WG_Chimpanzees.pdf). Thus, it is unlikely that HIV-1 (and other infectious disease) research in chimpanzees will be a feasible approach in the future. Therefore, investigators have turned to the only other available in vivo model for the study of HIV-1, humanized mice.

All four models of human immune system engraftment (Figure 1) have been used to study HIV-1, and these have been recently reviewed [7;25;26]. One major advantage of using NOD-scid and NSG mice is the robust immune systems that develop, including a mucosal immune system in the BLT model [19;20;26]. This permits investigation of the mucosal transmission route, effect of HIV-1 on mucosal immunity, and analyses of microbicides as pre-exposure prophylaxis therapy [27;28]. Recently, it was shown that NSG-BLT mice infected with HIV-1 generate human CD8 T cell responses that closely resemble cellular immune responses observed in infected humans. The virus undergoes a rapid, immune driven sequence evolution that leads to a reproducible escape from host immunity, recapitulating that observed in infected individuals [29]. BLT mice can also be infected with HIV-1 via the oral, rectal and vaginal routes, providing models for the study of these common routes of HIV-1 transmission [30-32]. HIV-1 infection of humanized mice leads to rapid depletion of peripheral and gastrointestinal CD4+ T cells [30] and an influx of human macrophages into the brain leading to neuropathogenesis [33;34] documenting the fidelity of the pathogenesis of disease with that of humans. A recent study done with NOD-scid BLT mice used intravital microscopy to demonstrate HIV-1 infected human CD4 T cells function as vehicles for dissemination of virus. The study showed that HIV-1 infected CD4 T cells within lymph nodes are highly motile, form multinucleated syncytia and establish long membrane tethers, which all may enhance cell to cell spread of HIV-1 [35].

Epstein Barr Virus (EBV)

In the original BRG Hu-SRC-SCID report, productive infection following EBV inoculation was demonstrated [17]. Using the NSG Hu-SRC-SCID model, infection with an EBV deficient in the nuclear oncogene EBNA3B, which in vitro is dispensable for B cell transformation, leads to aggressive diffuse large B cell human lymphomas in vivo [36]. This surprising finding led to identification of unique EBNA3B mutations in individuals with lymphomas, providing new insights into EBV-induction of B cell lymphomas [36]. A rare but devastating syndrome termed hemophagocytic lympho-histiocytosis has been modeled in EBV-infected humanized mice [37;38], and a model of erosive arthritis following EBV infection has been described [39]. Using HLA-A2 transgenic (Tg) mice engrafted with HLA-A2 HSC, EBV-restricted human CD8+ T cell responses have been detected as well as protective CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity [40-42]. Humanized mouse models are now allowing investigators to study pre-symptomatic stages of EBV infection, identify new mechanisms by which EBV infection can induce disease and EBV lymphomas, and provide model systems in which drugs can be tested for efficacy.

Dengue Virus (DENV)

Humans infected with DENV can develop a mild fever to acute febrile illness or progress to a severe capillary leakage syndrome (dengue hemorrhagic fever) following a second infection with a different DENV serotype [43]. However, little is known about the mechanisms by which this occurs [44]. Immunocompetent mice can be infected with DENV using intracranial high dose injections of virus or with mouse-adapted DENV. Mice deficient in both interferon α/β and γ receptors can also be infected but these models have not provided optimal tools for studies of dengue pathogenesis (reviewed in [44;45]). To address this need, humanized mice have been infected with DENV [42;46-51]. Key advances have been the recapitulation of clinical signs of dengue fever [50], the ability to infect humanized mice through infected Aedes aegypti mosquito bites [51], and the generation of HLA-A2-restricted human T cell responses in NSG-HLA-A2 Tg mice engrafted with HSC from an HLA-A2 positive donor [47] or in NSG mice engrafted with HLA-A2+ fetal tissues [42]. In humanized mice infected by mosquito bites, the human innate immune responses and disease symptoms in infected mice were more pronounced than following simple injection of the virus due to the activation of human innate immunity by factors in the mosquito bite [51].

Hepatitis C (HCV) and B (HBV)

More than 2 billion people worldwide are infected with HCV or HBV resulting in over 600,000 deaths each year (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/). HCV and HBV are hepatocyte-specific viruses and infect only humans (and chimpanzees) [52]. Human liver/chimeric mouse models have been engineered to develop small animal models of hepatitis. These models have in common mutations or transgenes that result in murine hepatocyte cell death making “room” for the engraftment of human hepatocytes (Table 1). These human liver/chimeric models have been used to study hepatitis B and C pathogenesis as well as the efficacy of anti-viral drugs [53-58]. In these models, levels of human hepatocyte engraftment and virus replication correlate with the severity of the immunodeficiency of the recipient, ultimately leading to development of scid or Rag2null mice bearing mutated IL2rγnull genes and expressing the mouse hepatocyte defect. Engraftment of these mice with human hepatocytes can result in up to 95% human hepatocyte chimerism [54;55]. Liver pathology, including inflammation, hepatitis and fibrosis were observed in these liver/chimeric/immune system-engrafted mice. Co-injection of human hepatocytes and HSC from the same donor into BRG mice expressing a fusion protein of the FK506 binding domain and caspase 8 under control of the albumin promoter led to the development of human hepatocytes and an autologous immune system in which an immune response to HCV infection could be investigated [55].

Table 1.

Humanized Hepatocyte Models for Infectious Disease

| Mouse strain | Common Name | Characteristics | Pathogen | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOCK Prkdcscid Tg(Alb1Plau)144Bri |

Alb-uPA/SCID | Expression of urokinase- type plasminogen activator (uPA) driven by the albumin promoter results in hemorrhaging associated with uPA’s fibrinolytic and fibrinogenolytic activities and accelerated hepatocyte death. Loss of transgene results in clonal repopulation of the liver with normal mouse hepatocytes |

Hepatitis B | [53] |

| STOCK Prkdcscid Lyst bg Tg(Alb1Plau)144Bri |

Alb-uPA/SCID BEIGE |

“” “” “” “” “” | Hepatitis B Hepatitis C Plasmodium falciparum |

[56- 58;66] |

| (B6;129)-Rag2tm1Fwa Fahtm1MgoIl2rgtm1Wjl |

FAH, FRG | A targeted deletion of the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolyse (Fah) gene models human tyrosinemia type I. Treatment of mice with 2- (2-nitro-4- trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1, 3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC) is required prior to and during early stages of hepatocyte engraftment. High incidence of lethality prior to engraftment |

Hepatitis B & C | [54] |

| “” “” “” “” “” “” | FAH, FRG | “” “” “” “” “” “” “” |

Plasmodium

falciparum |

[65] |

| C.Cg Rag2tm1Fwa Il2rg tm1CgnTg(Alb- FKBP12/CASP8)#Lsu |

AFC8 | A fusion protein of the FK-506 binding domain (FKBP) and caspase 8 under control of the albumin promoter. Treatment with the FKBP dimerizer results in inducible hepatocyte suicide. Mice can be repopulated with human hepatocytes and HSC |

Hepatitis C | [55] |

Additional Humanized Mouse Models of Virus Infection

A number of additional virus infection models are at early stages of development in humanized mice. These include cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1), influenza, and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (reviewed in [26]).

Humanized Mouse Models of Bacterial Infection

Salmonella enteric serovar Typhi (S. typhi)

This infectious bacterium is highly adapted to humans, fails to produce progressive infection in immunocompetent or unmanipulated (non-engrafted) immunodeficient mice, and causes typhoid fever, leading to an estimated 21 million cases and ~200,000 deaths a year [59]. Recently the first humanized mouse models of S. typhi have been described [60-62]. Using NSG Hu-SRC-SCID mice infected with S. typhi, granulomatous inflammation with mononuclear cell infiltration in the spleen was followed by rapid fatality. Screening of transposon pools in infected mice revealed previously unrecognized Salmonella virulence determinants [60]. Using BRG Hu-SRC-SCID mice, prolonged survival was associated with innate and adaptive human immune responses [61], and in some cases, neurological symptoms [62]. These reports highlight the differences in pathogenesis and lethality following S. typhi infection in the different strains of humanized mice providing novel models for the study of this infectious agent.

Humanized Mouse Models of Protozoan Infection

Plasmodium falciparum

More than 200 million new cases of malaria are diagnosed each year, resulting in over 650,000 deaths (WHO World Malaria Report, 2011). For the life cycle of the human (and chimpanzee [63]) specific infectious agent Plasmodium falciparum, both human hepatocytes and erythrocytes are required. Human liver/chimera models have been established (Table 1), but few human RBCs circulate in the blood of human HSC-engrafted mice despite the presence of erythroid progenitors in the BM [19;20]. To model the erythrocyte portion of the life cycle, repeated injection of packed RBCs into NSG mice preceding infection with P. falciparum allowed the therapeutic efficacy of selective inhibitors of P. falciparum to be assessed [64]. For study of liver-stages of Plasmodium falciparum, liver/chimera models were used (Table 1) [65;66]. In the Vaughan et al study, liver/chimera mice were injected with RBCs, permitting transition of liver stage infection to blood stage infection [65]. Mice co-engrafted with human hepatocytes and HSC from the same donor [55], along with injection of human RBCs could provide a model where all stages of the life cycle of P. falciparum can be studied in the presence of a human immune system.

Conclusion

Humanized mice are rapidly becoming experimental tools of choice to investigate human infectious agents that do not infect other species, or poorly recapitulate infection, pathogenesis, and immune responses. However, it must be cautioned that there remain a number of limitations in the use of humanized mice for infectious disease studies. Many of the limitations inherent in humanized mice are due to mouse versus human-specific differences in the molecules required for human hematopoietic and immune system development (reviewed in [19;20]). Expression of human transgenes and targeted inactivation of mouse genes encoding factors that control the development and function of human cells are currently being used to address these remaining limitations. Studies of emerging infectious human diseases drive the need of basic research that supports development and optimization of humanized mouse models for engraftment with a range of human tissues that can support infection with emerging pathogens. Optimized models will need to be able to mount vigorous humoral and cell-mediated human immune responses and permit the rapid testing of experimental vaccines. Moreover the threat of bioterrorism mandates optimization of existing humanized mouse model systems and technological improvements to ensure appropriate humanized mouse models that will support infection with bio-engineered human pathogens. In conclusion, humanized mice are promising pre-clinical bridges for the study of the pathogenesis and efficacy of drugs on human infectious agents prior to their entry into clinical trials.

Highlights.

Many human infectious diseases are caused by pathogens that do not infect rodents

Humanized mice serve as a preclinical bridge for in vivo studies of human pathogens

Next generation humanized mouse models will accelerate drug discovery

Limitations of humanized mice are being addressed using new technologies

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health research grants AI046629, DK32520, a Cancer Core Grant CA034196, a grant from the University of Massachusetts Center for AIDS Research, P30 AI042845 and a grant from the Helmsley Charitable Trust. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. These funding sources had no involvement in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS MAB and DLG are consultants for The Jackson Laboratory.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

References and recommended reading

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Belser JA, Szretter KJ, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Use of animal models to understand the pandemic potential of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Adv.Virus Res. 2009;73:55–97. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(09)73002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasgupta G, BenMohamed L. Of mice and not humans: how reliable are animal models for evaluation of herpes CD8(+)-T cell-epitopes-based immunotherapeutic vaccine candidates? Vaccine. 2011;29:5824–5836. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh RM, Che JW, Brehm MA, Selin LK. Heterologous immunity between viruses. Immunol.Rev. 2010;235:244–266. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatziioannou T, Evans DT. Animal models for HIV/AIDS research. Nat.Rev.Microbiol. 2012;10:852–867. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mestas J, Hughes CC. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J.Immunol. 2004;172:2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seok J, Warren HS, Cuenca AG, Mindrinos MN, Baker HV, Xu W, Richards DR, Donald-Smith GP, Gao H, Hennessy L, et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2013:3507–3512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berges BK, Rowan MR. The utility of the new generation of humanized mice to study HIV-1 infection: transmission, prevention, pathogenesis, and treatment. Retrovirology. 2011;8:65–84. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe ND, Dunavan CP, Diamond J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature. 2007;447:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature05775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB. Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature. 1988;335:256–259. doi: 10.1038/335256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Shultz LD, Lieberman M, Weissman IL. The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science. 1988;241:1632–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB, Spector DH, Spector SA. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human-PBL-SCID mice. Science. 1991;251:791–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1990441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Lieberman M, Weissman IL, McCune JM. Infection of the SCID-hu mouse by HIV-1. Science. 1988;242:1684–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.3201256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL. Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat.Rev Immunol. 2007;7:118–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, Suzue K, Kawahata M, Hioki K, Ueyama Y, Koyanagi Y, Sugamura K, Tsuji K, Heike T, Nakahata T. NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood. 2002;100:3175–3182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, Gillies SD, King M, Mangada J, Greiner DL, Handgretinger R. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2rγnull mice engrafted with mobilized human hematopoietic stem cell. J.Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Traggiai E, Chicha L, Mazzucchelli L, Bronz L, Piffaretti JC, Lanzavecchia A, Manz MG. Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice. Science. 2004;304:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1093933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa F, Yasukawa M, Lyons B, Yoshida S, Miyamoto T, Yoshimoto G, Watanabe T, Akashi K, Shultz LD, Harada M. Development of functional human blood and immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2 receptor gamma chain null mice. Blood. 2005;106:1565–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Strowig T, Willinger T, Eynon EE, Flavell RA, Manz MG. Human Hemato-Lymphoid System Mice: Current Use and Future Potential for Medicine. Annu.Rev.Immunol. 2013:635–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shultz LD, Brehm MA, Garcia-Martinez JV, Greiner DL. Humanized mice for immune system investigation: progress, promise and challenges. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2012;12:786–798. doi: 10.1038/nri3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, Nugeyre MT, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, xler-Blin C, Vezinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, Rozenbaum W, Montagnier L. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, Shearer GM, Kaplan M, Haynes BF, Palker TJ, Redfield R, Oleske J, Safai B. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984;224:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fultz PN, Siegel RL, Brodie A, Mawle AC, Stricker RB, Swenson RB, Anderson DC, McClure HM. Prolonged CD4+ lymphocytopenia and thrombocytopenia in a chimpanzee persistently infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J.Infect.Dis. 1991;163:441–447. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson BK, Stone GA, Godec MS, Asher DM, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr. Long-term observations of human immunodeficiency virus-infected chimpanzees. AIDS Res.Hum.Retroviruses. 1993;9:375–378. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denton PW, Garcia JV. Humanized Mouse Models of HIV Infection. AIDS Rev. 2011;13:135–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akkina R. New generation humanized mice for virus research: comparative aspects and future prospects. Virology. 2013;435:14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoddart CA, Maidji E, Galkina SA, Kosikova G, Rivera JM, Moreno ME, Sloan B, Joshi P, Long BR. Superior human leukocyte reconstitution and susceptibility to vaginal HIV transmission in humanized NOD-scid IL-2Rgamma(−/−) (NSG) BLT mice. Virology. 2011;417:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denton PW, Garcia JV. Mucosal HIV-1 transmission and prevention strategies in BLT humanized mice. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **29.Dudek TE, No DC, Seung E, Vrbanac VD, Fadda L, Bhoumik P, Boutwell CL, Power KA, Gladden AD, Battis L, Mellors EF, Tivey TR, Gao X, Altfeld M, Luster AD, Tager AM, Allen TM. Rapid evolution of HIV-1 to functional CD8(+) T cell responses in humanized BLT mice. Sci.Transl.Med. 2012;4:143ra98. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003984. BLT mice infected with HIV-1 develop human HIV-1-specific CD8(+) T cell responses and viral sequence evolution leading to rapid and reproducible escape from the immune responses that recapitulate the immune and virus responses observed in HIV-1 infected individuals. This validates the BLT model for studies of the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection.

- *30.Denton PW, Othieno F, Martinez-Torres F, Zou W, Krisko JF, Fleming E, Zein S, Powell DA, Wahl A, Kwak YT, Welch BD, Kay MS, Payne DA, Gallay P, Appella E, Estes JD, Lu M, Garcia JV. One percent tenofovir applied topically to humanized BLT mice and used according to the CAPRISA 004 experimental design demonstrates partial protection from vaginal HIV infection, validating the BLT model for evaluation of new microbicide candidates. J.Virol. 2011;85:7582–7593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00537-11. This paper uses BLT mice to document that an experimental microbicide can block HIV-1 infection via the vaginal route, permitting direct analysis of the effectiveness of a microbicide prior to entering clincial trials.

- 31.Denton PW, Krisko JF, Powell DA, Mathias M, Kwak YT, Martinez-Torres F, Zou W, Payne DA, Estes JD, Garcia JV. Systemic administration of antiretrovirals prior to exposure prevents rectal and intravenous HIV-1 transmission in humanized BLT mice. PLoS.ONE. 2010;5:e8829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahl A, Swanson MD, Nochi T, Olesen R, Denton PW, Chateau M, Garcia JV. Human Breast Milk and Antiretrovirals Dramatically Reduce Oral HIV-1 Transmission in BLT Humanized Mice. PLoS.Pathog. 2012;8:e1002732. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002732. Breast milk from HIV-1 infected mothers is a common transmission route for HIV-1 infection. This paper describes the first humanized mouse model for studying transmission of HIV-1 through the breast milk.

- 33.Dash PK, Gorantla S, Gendelman HE, Knibbe J, Casale GP, Makarov E, Epstein AA, Gelbard HA, Boska MD, Poluektova LY. Loss of neuronal integrity during progressive HIV-1 infection of humanized mice. J.Neurosci. 2011;31:3148–3157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5473-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorantla S, Makarov E, Finke-Dwyer J, Castanedo A, Holguin A, Gebhart CL, Gendelman HE, Poluektova L. Links between progressive HIV-1 infection of humanized mice and viral neuropathogenesis. Am.J.Pathol. 2010;177:2938–2949. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **35.Murooka TT, Deruaz M, Marangoni F, Vrbanac VD, Seung E, von Andrian UH, Tager AM, Luster AD, Mempel TR. HIV-infected T cells are migratory vehicles for viral dissemination. Nature. 2012;490:283–287. doi: 10.1038/nature11398. This paper describes using multiphoton intravital microscopy the ability of HIV-1 infected CD4 T cells to form multinucelated syncytia to permit cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1 via tethering interactions using HIV envelope-dependent cell fusion.

- 36.White RE, Ramer PC, Naresh KN, Meixlsperger S, Pinaud L, Rooney C, Savoldo B, Coutinho R, Bodor C, Gribben J, Ibrahim HA, Bower M, Nourse JP, Gandhi MK, Middeldorp J, Cader FZ, Murray P, Munz C, Allday MJ. EBNA3B-deficient EBV promotes B cell lymphomagenesis in humanized mice and is found in human tumors. J.Clin.Invest. 2012;122:1487–1502. doi: 10.1172/JCI58092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato K, Misawa N, Nie C, Satou Y, Iwakiri D, Matsuoka M, Takahashi R, Kuzushima K, Ito M, Takada K, Koyanagi Y. A novel animal model of Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in humanized mice. Blood. 2011;117:5663–5673. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-305979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imadome K, Yajima M, Arai A, Nakazawa A, Kawano F, Ichikawa S, Shimizu N, Yamamoto N, Morio T, Ohga S, Nakamura H, Ito M, Miura O, Komano J, Fujiwara S. Novel mouse xenograft models reveal a critical role of CD4+ T cells in the proliferation of EBV-infected T and NK cells. PLoS.Pathog. 2011;7:e1002326. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuwana Y, Takei M, Yajima M, Imadome K, Inomata H, Shiozaki M, Ikumi N, Nozaki T, Shiraiwa H, Kitamura N, Takeuchi J, Sawada S, Yamamoto N, Shimizu N, Ito M, Fujiwara S. Epstein-Barr virus induces erosive arthritis in humanized mice. PLoS.ONE. 2011;6:e26630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strowig T, Gurer C, Ploss A, Liu YF, Arrey F, Sashihara J, Koo G, Rice CM, Young JW, Chadburn A, Cohen JI, Munz C. Priming of protective T cell responses against virus-induced tumors in mice with human immune system components. J.Exp.Med. 2009;206:1423–1434. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shultz LD, Saito Y, Najima Y, Tanaka S, Ochi T, Tomizawa M, Doi T, Sone A, Suzuki N, Fujiwara H, Yasukawa M, Ishikawa F. Generation of functional human T-cell subsets with HLA-restricted immune responses in HLA class I expressing NOD/SCID/IL2r gamma(null) humanized mice. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2010;107:13022–13027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000475107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaiswal S, Pazoles P, Woda M, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Brehm MA, Mathew A. Enhanced humoral and HLA-A2-restricted dengue virus-specific T-cell responses in humanized BLT NSG mice. Immunol. 2012;136:334–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin.Microbiol.Rev. 1998;11:480–496. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothman AL. Immunity to dengue virus: a tale of original antigenic sin and tropical cytokine storms. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2011;11:532–543. doi: 10.1038/nri3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zompi S, Harris E. Animal models of dengue virus infection. Viruses. 2012;4:62–82. doi: 10.3390/v4010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bente DA, Melkus MW, Garcia JV, Rico-Hesse R. Dengue fever in humanized NOD/SCID mice. J.Virol. 2005;79:13797–13799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13797-13799.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaiswal S, Pearson T, Friberg H, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Rothman AL, Mathew A. Dengue virus infection and virus-specific HLA-A2 restricted immune responses in humanized NOD-scid IL2rgammanull mice. PLoS.ONE. 2009;4:e7251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuruvilla JG, Troyer RM, Devi S, Akkina R. Dengue virus infection and immune response in humanized RAG2(−/−)gamma(c)(−/−) (RAG-hu) mice. Virology. 2007;369:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mota J, Rico-Hesse R. Humanized mice show clinical signs of dengue fever according to infecting virus genotype. J.Virol. 2009;83:8638–8645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00581-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mota J, Rico-Hesse R. Dengue virus tropism in humanized mice recapitulates human dengue fever. PLoS.ONE. 2011;6:e20762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Cox J, Mota J, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Diamond MS, Rico-Hesse R. Mosquito bite delivery of dengue virus enhances immunogenicity and pathogenesis in humanized mice. J.Virol. 2012;86:7637–7649. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00534-12. This paper demonstrates using humanized micel the critical role that factors in the mosquito bite have in activation of innate immunity in individuals that may have an important role in the infection and disease pathogenesis of DENV-infected individuals.

- 52.Morin TJ, Broering TJ, Leav BA, Blair BM, Rowley KJ, Boucher EN, Wang Y, Cheslock PS, Knauber M, Olsen DB, Ludmerer SW, Szabo G, Finberg RW, Purcell RH, Lanford RE, Ambrosino DM, Molrine DC, Babcock GJ. Human monoclonal antibody HCV1 effectively prevents and treats HCV infection in chimpanzees. PLoS.Pathog. 2012;8:e1002895. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brezillon N, Brunelle MN, Massinet H, Giang E, Lamant C, DaSilva L, Berissi S, Belghiti J, Hannoun L, Puerstinger G, Wimmer E, Neyts J, Hantz O, Soussan P, Morosan S, Kremsdorf D. Antiviral activity of Bay 41-4109 on hepatitis B virus in humanized Alb-uPA/SCID mice. PLoS.ONE. 2011;6:e25096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bissig KD, Wieland SF, Tran P, Isogawa M, Le TT, Chisari FV, Verma IM. Human liver chimeric mice provide a model for hepatitis B and C virus infection and treatment. J.Clin.Invest. 2010;120:924–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI40094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **55.Washburn ML, Bility MT, Zhang L, Kovalev GI, Buntzman A, Frelinger JA, Barry W, Ploss A, Rice CM, Su L. A humanized mouse model to study hepatitis C virus infection, immune response, and liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1334–1344. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.001. The paper describes for the first time a humanized mouse model for hepatitis virus infection in which the human immune response to the virus can also be investigated.

- 56.Mercer DF, Schiller DE, Elliott JF, Douglas DN, Hao C, Rinfret A, Addison WR, Fischer KP, Churchill TA, Lakey JR, Tyrrell DL, Kneteman NM. Hepatitis C virus replication in mice with chimeric human livers. Nat.Med. 2001;7:927–933. doi: 10.1038/90968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown RJ, Hudson N, Wilson G, Rehman SU, Jabbari S, Hu K, Tarr AW, Borrow P, Joyce M, Lewis J, Zhu LF, Law M, Kneteman N, Tyrrell DL, McKeating JA, Ball JK. Hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein fitness defines virus population composition following transmission to a new host. J.Virol. 2012;86:11956–11966. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01079-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lutgehetmann M, Bornscheuer T, Volz T, Allweiss L, Bockmann JH, Pollok JM, Lohse AW, Petersen J, Dandri M. Hepatitis B virus limits response of human hepatocytes to interferon-alpha in chimeric mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:2074–2083. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Typhoid fever. N.Engl.J.Med. 2002;347:1770–1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **60.Libby SJ, Brehm MA, Greiner DL, Shultz LD, McClelland M, Smith KD, Cookson BT, Karlinsey JE, Kinkel TL, Porwollik S, Canals R, Cummings LA, Fang FC. Humanized nonobese diabetic-scid IL2rgammanull mice are susceptible to lethal Salmonella Typhi infection. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2010;107:15589–15594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005566107. This paper describes the first humanized mouse model based on NSG mice for the study of Salmonella Thypi infection and by screening transponson pools identified previously unknown Salmonella virulence factors.

- **61.Song J, Willinger T, Rongvaux A, Eynon EE, Stevens S, Manz MG, Flavell RA, Galan JE. A mouse model for the human pathogen Salmonella typhi. Cell Host.Microbe. 2010;8:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.003. This paper describes the first humanized mouse model based on BRG mice for the study of Salmonella Thypi infection and documented the development of human innate and adaptive immune responses, and the role of a Salmonella toxin in the establishment of a persistent infection.

- 62.Firoz MM, Pek EA, Chenoweth MJ, Ashkar AA. Humanized mice are susceptible to Salmonella typhi infection. Cell Mol.Immunol. 2011;8:83–87. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daubersies P, Thomas AW, Millet P, Brahimi K, Langermans JA, Ollomo B, BenMohamed L, Slierendregt B, Eling W, Van BA, Dubreuil G, Meis JF, Guerin-Marchand C, Cayphas S, Cohen J, Gras-Masse H, Druilhe P. Protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria in chimpanzees by immunization with the conserved pre-erythrocytic liver-stage antigen 3. Nat.Med. 2000;6:1258–1263. doi: 10.1038/81366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jimenez-Diaz MB, Mulet T, Viera S, Gomez V, Garuti H, Ibanez J, varez-Doval A, Shultz LD, Martinez A, Gargallo-Viola D, ngulo-Barturen I. Improved murine model of malaria using Plasmodium falciparum competent strains and non-myelodepleted NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull mice engrafted with human erythrocytes. Antimicrob.Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4533–4536. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00519-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **65.Vaughan AM, Mikolajczak SA, Wilson EM, Grompe M, Kaushansky A, Camargo N, Bial J, Ploss A, Kappe SH. Complete Plasmodium falciparum liver-stage development in liver-chimeric mice. J.Clin.Invest. 2012;122:3618–3628. doi: 10.1172/JCI62684. This paper describes the use of a human liver/chimeric mouse model engrafted with human RBCs that permitted for the first time the investigation of Plasmodium falciparum infection transition from the liver stage to blood stage infection.

- 66.Morosan S, Hez-Deroubaix S, Lunel F, Renia L, Giannini C, Van Rooijen N, Battaglia S, Blanc C, Eling W, Sauerwein R, Hannoun L, Belghiti J, Brechot C, Kremsdorf D, Druilhe P. Liver-stage development of Plasmodium falciparum, in a humanized mouse model. J.Infect.Dis. 2006;193:996–1004. doi: 10.1086/500840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mosier DE, Baird SM, Kirven MB. EBV-associated B-cell lymphomas following transfer of human peripheral blood lymphocytes to mice with severe combined immune deficiency. Curr.Top.Microbiol.Immunol. 1990;166:317–323. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75889-8_39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.King MA, Covassin L, Brehm MA, Racki W, Pearson T, Leif J, Laning J, Fodor W, Foreman O, Burzenski L, Chase T, Gott B, Rossini AA, Bortell R, Shultz LD, Greiner DL. Hu-PBL-NOD-scid IL2rgnull mouse model of xenogeneic graft-versus-host-like disease and the role of host MHC. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 2009;157:104–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brehm MA, Cuthbert A, Yang C, Miller DM, DiIorio P, Laning J, Burzenski L, Gott B, Foreman O, Kavirayani A, Herlihy M, Rossini AA, Shultz LD, Greiner DL. Parameters for establishing humanized mouse models to study human immunity: analysis of human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment in three immunodeficient strains of mice bearing the IL2rgamma(null) mutation. Clin.Immunol. 2010;135:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lan P, Tonomura N, Shimizu A, Wang S, Yang YG. Reconstitution of a functional human immune system in immunodeficient mice through combined human fetal thymus/liver and CD34+ cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108:487–492. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Melkus MW, Estes JD, Padgett-Thomas A, Gatlin J, Denton PW, Othieno FA, Wege AK, Haase AT, Garcia JV. Humanized mice mount specific adaptive and innate immune responses to EBV and TSST-1. Nat.Med. 2006;12:1316–1322. doi: 10.1038/nm1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]