Abstract

The organic cation transporter (OCT) 3 is widely expressed in various organs in humans, and involved in the disposition of many exogenous and endogenous compounds. Several lines of evidence have suggested that OCT3 expressed in the brain plays an important role in the regulation of neurotransmission. Relative to wild-type (WT) animals, Oct3 knockout (KO) mice have displayed altered behavioral and neurochemical responses to psychostimulants such as amphetamine (AMPH) and methamphetamine. In the present study, both in vitro and in vivo approaches were utilized to explore potential mechanisms underlying the disparate neuropharmacological effects observed following AMPH exposure in Oct3 KO mice. In vitro uptake studies conducted in OCT3 transfected cells indicated that dextroamphetamine (d-AMPH) is not a substrate of OCT3. However, OCT3 was determined to be a high-capacity and low-affinity transporter for the neurotransmitters dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), and serotonin (5-HT). Inhibition studies demonstrated that d-AMPH exerts relatively weak inhibitory effects on the OCT3-mediated uptake of DA, NE, 5-HT, and the model OCT3 substrate 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide. The IC50 values were determined to be 41.5 ± 7.5 and 24.1 ± 7.0 μM for inhibiting DA and 5-HT uptake, respectively, while 50% inhibition of NE and 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide uptake was not achieved by even the highest concentration of d-AMPH applied (100 μM). Furthermore, the disposition of d-AMPH in various tissues including the brain, liver, heart, kidney, muscle, intestine, spleen, testis, uterus, and plasma were determined in both male and female Oct3 KO and WT mice. No significant difference was observed between either genotypes or sex in all tested organs and tissues. Our findings suggest that OCT3 is not a prominent factor influencing the disposition of d-AMPH. Additionally, based upon the inhibitory potency observed in vitro, d-AMPH is unlikely to inhibit the uptake of monoamines mediated by OCT3 in the brain. Differentiated neuropharmacological effects of AMPHs noted between Oct3 KO and WT mice appear to be due to the absence of Oct3 mediated uptake of neurotransmitters in the KO mice.

Keywords: amphetamine, inhibitor, monoamine neurotransmitters, organic cation transporter 3, substrate

Organic cation transporters (OCTs), belonging to the SLC22 gene family, are involved in the absorption, distribution, recycling, and elimination of endogenous compounds such as amines, as well as various therapeutic agents, other xenobiotics, and toxins that are positively charged at physiological pH. There are three primary OCT isoforms of interest, OCT1 (SLC22A1), OCT2 (SLC22A2) and OCT3 (SLC22A3), which share high sequence similarities and a common 12-transmembrane domain structure (Koepsell 2004; Koepsell et al. 2007). In humans, OCT1 is most prominently expressed in the liver, whereas in rodents, it is most abundantly expressed in the liver, kidney, and small intestine (Gorboulev et al. 1997; Koepsell et al. 2003). Relative to OCT1, the expression of OCT2 in humans is essentially restricted to the kidney which serves as the main organ of OCT2 expression (Okuda et al. 1996; Gorboulev et al. 1997). OCT3, also termed as extraneuronal monoamine transporter, is widely distributed in various tissues in humans. Of particular neuropharmacologic interest, OCT3 is widely expressed throughout the human and rodent brain (Wu et al. 1998; Schmitt et al. 2003; Haag et al. 2004; Vialou et al. 2004; Amphoux et al. 2006; Gasser et al. 2006; Cui et al. 2009). In addition to mediating the transport of a variety of exogenous compounds, OCT3 is capable of transporting the major monoamine neurotransmitters including dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), and serotonin (5-HT) (Grundemann et al. 1998; Wu et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006). The importance of OCT3 in the regulation of neurotransmission has now been documented in a number of animal studies (Vialou et al. 2004, 2008; Kitaichi et al. 2005; Aoyama et al. 2006; Baganz et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2009; Wultsch et al. 2009), and more recently, in humans (Cui et al. 2009).

Amphetamines (AMPH) are widely used in the treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, and are also among the most popular drugs of recreational abuse. AMPH is believed to produce its neurotherapeutic, stimulatory, and in some instances, neurotoxic effects by rapidly increasing extracellular DA concentrations in the brain (Sulzer et al. 2005). Direct blockade of the dopamine transporter (DAT) and reversal of DAT transport are thought to contribute to the overall mechanism by which AMPH enhances extracellular DA concentrations and exerts its neuropharmacologic effects (Volz et al. 2007). Interestingly, in addition to its action as an inhibitor of DAT, AMPH was determined to be an OCT3 inhibitor as evidenced by its inhibitory effect on OCT3-mediated uptake of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), a widely utilized OCT3 model substrate (Wu et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006). As DA is a known substrate of OCT3 (Wu et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006), the question may be raised as to whether OCT3 inhibition plays a significant role in AMPH-induced increases of extracellular DA concentrations in the brain. In an effort to enhance the understanding of dopaminergic neurotransmission and homeostasis and its modulation by therapeutic agents, a series of studies were carried out.

The Oct3 knockout (KO) mouse developed (Zwart et al. 2001), serves as an ideal in vivo model to assess the physiologic role of the transporter as well as the pharmacology of selected pharmacologic agents. Accordingly, the mice were subjected to comprehensive behavioral studies (Vialou et al. 2008). The locomotor response to acute administration of high dose AMPH was significantly higher in Oct3 KO mice than that in wild-type (WT) controls. Consistent with these behavioral findings, a recent microdialysis study revealed that high doses of the structural congener methamphetamine produced significantly higher extracellular DA levels in the striatum of Oct3 KO mice relative to that observed in WT mice (Cui et al. 2009). It was hypothesized by the investigators that these enhanced psychostimulant effects were due to the lack of Oct3-mediated DA reuptake in Oct3 KO mice. However, other possibilities could not be excluded, e.g. the observed effects may be anticipated to occur following methamphetamine brain accumulation in Oct3 KO mice as a result of a deficit of Oct3 in the blood–brain barrier and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Accordingly, a pharmacokinetic study was conducted in order to determine if differences existed in the disposition of AMPH within the brain of Oct3 KO mice compared with WT. This study was warranted in order to elucidate the mechanism(s) underlying the differentiated responses to psychostimulants previously documented between Oct3 KO animals relative to the WT controls (i.e. pharmacokinetic vs. pharmacodynamic effects). As AMPH is a known inhibitor of OCT3, and also shares structural similarity with other known OCT3 substrates NE and DA, it is sometimes assumed to serve as an OCT3 substrate as well. However, to our knowledge, this assumption has never been confirmed by direct assessment to date.

In the present study, the interactions between OCT3 and the more active and clinically administered isomer, dextroamphetamine (d-AMPH) were investigated using complimentary in vitro and in vivo approaches. The capacity of OCT3 in the transport of d-AMPH was determined by comparing the uptake of d-AMPH in OCT3 transfected cells in parallel with vector transfected control cells. An assessment of the neurotransmitters NE, DA, and 5-HT as substrates of the OCT3 transporter was conducted utilizing an established in vitro incubation assay. Furthermore, the potential inhibitory effects of d-AMPH on OCT3-mediated NE, DA, and 5-HT uptake were characterized. Finally, a comprehensive pharmacokinetic study was conducted to determine the disposition of d-AMPH in the brain as well as within other major organs of Oct3 KO mice and WT animals.

Materials and methods

Animal models

The Organic Cation Transporter 3 (Oct3/Slc22a3) KO mouse of the FVB inbred strain was kindly provided by Dr. Alfred Schinkel of the Netherlands Cancer Institute. The Oct3 KO mice were initially sent to Charles River Laboratories for re-derivation prior to delivery to the Medical University of South Carolina animal care facilities where all experiments were carried out and a breeding colony was then established. Age and sex-matched inbred FVB mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories, served as WT controls. Animals were housed in a colony room with temperature maintained at 22 ± 1°C on a 12-h light : dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM and off at 7:00 PM. Animals were allowed to acclimate to their cages and colony room for a minimum of 7 days before any study procedure. All protocols were approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in compliance with the guidelines of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80–123, revised 1996).

Research chemicals

Dextroamphetamine (as its sulfate salt) was a gift provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse Research Resource Drug Supply System. The established OCT3 substrates MPP+, and 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide (4-Di-1-ASP) were obtained from Sigma Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents were of high analytical grade and obtained commercially.

Uptake of d-AMPH in OCT3-transfected cells

HEK293 cells stably transfected with human OCT3 were established (Grundemann et al. 1998) and utilized in the present study. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity. Cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL/well. Culture medium was replaced every 2 days until cells reached confluence. After reaching confluence, cells were pre-incubated at 37°C for 30 min with assay buffer (serum-free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). d-AMPH was then added to the system attaining a final concentration of 5 μM, and an additional 30 min incubation period followed. Following incubation, the solutions were discarded, and the cells were washed three times with ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and solubilized with 1% Triton X-100. The concentrations of d-AMPH were determined utilizing an established high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay (Zhu et al. 2006). Examples of typical HPLC chromatograms of d-AMPH are found in the Supporting information. Additionally, the established OCT3 substrates MPP+ (5 μM) and 4-Di-1-ASP (5 μM) were included in the study as positive substrate controls. The concentrations of MPP+ and 4-Di-1-ASP were determined using HPLC-fluorescence assay and a fluorescence microplate reader, respectively (Naoi et al. 1987; Rytting et al. 2007). The amounts of d-AMPH, MPP+, and 4-Di-1-ASP in each sample were standardized with the protein content as determined by a BCA Pierce Protein Kit (Rockford, IL, USA). Specific d-AMPH, MPP+, and 4-Di-1-ASP uptake mediated by OCT3 was calculated by subtracting the uptake in vector cells from that in OCT3 transfected cells.

Determination of OCT3 as a transporter of the major monoamine neurotransmitters DA, NE, and 5-HT

Organic cation transporter3-mediated uptake of DA, NE, and 5-HT was determined utilizing the cells stably transfected with OCT3 and the vector cells as the control for nonspecific uptake. The cells were cultured in 24-well cell culture plates. After reaching confluence, the cells were incubated with various concentrations of DA, NE, and 5-HT (0.01–3 mM) at 37°C for 10 min. After incubation, the medium was discarded, and the cells were washed three times with 1 mL ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline, and solubilized in 1% Triton X-100. The intracellular concentrations of each monoamine were measured via an ESA CoulArray HPLC system (ESA, Chelmsford, MA, USA) coupled with electrochemical detection (Milford, MA, USA). The analytical cell (Model 5014B) was set at detector 1 = –150 mV and detector 2 = 200 mV. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Phenomenex Luna C18 (2) 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm reversed-phase column preceded by a 4 × 3 mm C18 guard column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at room temperature. The mobile phase was a mixture containing 90 mM sodium dihydrogen phosphate, 50 mM citric acid, 1.7 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid, 50 μM EDTA, and 10% acetonitrile (pH 3.0), and delivered at a rate of 1 mL/min. The lower limit of quantification of three monoamines was determined to be 10 pM. The intra-day and inter-day standard deviations were found to be within ± 10%. The concentrations of each monoamine were standardized to the protein content as determined by a Pierce BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). OCT3 specific uptake was determined by subtracting the uptake in vector transfected cells from that of OCT3 transfected cells. The apparent Michaelis–Menten constants Vmax and Km were calculated by fitting the data to the Michaelis–Menten equation V = Vmax[S]/Km + [S], where V is the uptake velocity and [S] is the substrate concentration.

Inhibition of OCT3-mediated uptake of neurotransmitters by d-AMPH

Inhibition experiments were carried out in 24-well cell culture plates when the cells reached confluence. The cells were equilibrated with the assay buffer at 37°C for 30 min followed by a pre-incubation with various concentrations of d-AMPH (1–100 μM) for 10 min. After pre-incubation, the incubation solutions were replaced with the same concentrations of d-AMPH premixed with the substrates NE (10 μM), DA (10 μM), 5-HT (10 μM), and 4-Di-1-ASP (5 μM) for an additional 10 min incubation period at 37°C. Uptake activity was terminated by aspirating the solution, and washing the cells three times with 1 mL ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline. After this, the cells were solubilized with 1% Triton X-100, and the intracellular retentions of substrates were determined by aforementioned methods. The relative OCT3 activity remained in the cells treated with d-AMPH was calculated using the following equation: Relative activity(% of control) = (COCT3-treated – Cvector-treated)/(COCT3-untreated – Cvector-untreated) where COCT3-treated and Cvector-treated are the intracellular substrate concentrations in OCT3 and vector cells, respectively, treated with d-AMPH while COCT3-untreated and Cvector-untreated are the substrate concentrations in OCT3 and vector cells, respectively, without d-AMPH treatment.

Disposition of d-AMPH in WT and Oct3 knockout mice

An in vivo study was performed for the purpose of determining the potential influence of OCT3 upon the pharmacokinetic disposition of d-AMPH. The study included eight groups divided by genotypes (WT and Oct3 KO), sex (male and female), and two time points (20 and 40 min after d-AMPH dosing). Each group contained three mice. d-AMPH was administered via i.p. injection at a dose of 3.0 mg/kg with the injection volume limited to 10 μL/g mouse. At the 20 and 40 min post-administration time points, respective groups of mice were then i.p. injected with pentobarbital 100 mg/kg to produce deep anesthesia prior to surgical exposure of the heart. Approximately 0.3 mL of blood from the right atrium was collected via direct heart puncture using a syringe and immediately transferred to blood collection tubes (BD Vacutainer™, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) held on ice containing sodium heparin, and centrifuged at 3000 g for 20 min to separate plasma from other whole blood components. The plasma was then removed and stored at –70°C until analysis. Other organs and tissues including the brain, liver, heart, kidney, muscle, intestine, spleen, testis, and uterus were immediately collected by dissection, individually weighed, and stored in a freezer at –70°C until analysis.

The tissue samples were prepared by homogenizing each in a fivefold volume of Hank's balanced salt solution using a hand-held Polytron® homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY, USA). The concentrations of d-AMPH in collected tissues were analyzed utilizing a validated HPLC method published previously (Zhu et al. 2006). An additional pharmacokinetic study was performed to measure the plasma and brain concentrations at 30 min after administration of 1.5 mg/kg d-AMPH in six WT and six Oct3 KO males.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for significant differences was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. A probability of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The IC50 in d-AMPH inhibition study was the concentration of d-AMPH at which 50% of substrate was uptake by OCT3 relative to that without the treatment of d-AMPH. The IC50 values were calculated via nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (Intuitive Software for Science, San Diego, CA, USA). All data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Results

OCT3 does not mediate the transport of d-AMPH

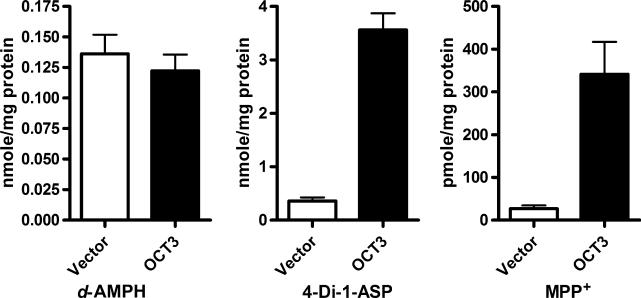

HEK293 cells stably transfected with OCT3 were utilized to determine whether OCT3 could efficiently transport the psychostimulant d-AMPH. The prototypical OCT3 substrates MPP+ and 4-Di-1-ASP were employed in the study as positive controls. The intracellular uptake of MPP+ and 4-Di-1-ASP in OCT3 transfected cells was 9.9 and 12.6 times greater than that in vector control cells. In contrast, the intracellular accumulation of d-AMPH did not differ between OCT3 and control cells, indicating d-AMPH is not a transportable substrate of OCT3 under our experimental conditions (Fig. 1). The intracellular d-AMPH concentrations in the OCT3 transfected and vector control cells observed in the present study are calculated to be approximately 19 μM based upon a previously reported intracellular space value of 6.7 μL/mg protein in HEK293 cells (Martel et al. 1996). The higher d-AMPH concentrations in the intracellular compartment relative to that in the incubation buffer (5 μM) are likely due to the protein binding occurring within the cells and/or the uptake mediated by an yet unidentified transporter(s).

Fig. 1.

Uptake of dextroamphetamine (d-AMPH), 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide (4-Di-1-ASP), and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) by organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3). Intracellular accumulation of d-AMPH, 4-Di-1-ASP, and MPP+ in OCT3 and vector transfected cells were measured after incubation 30 min at 37 C. Data are represented as the mean with the error bar indicating the SEM of four independent measurements.

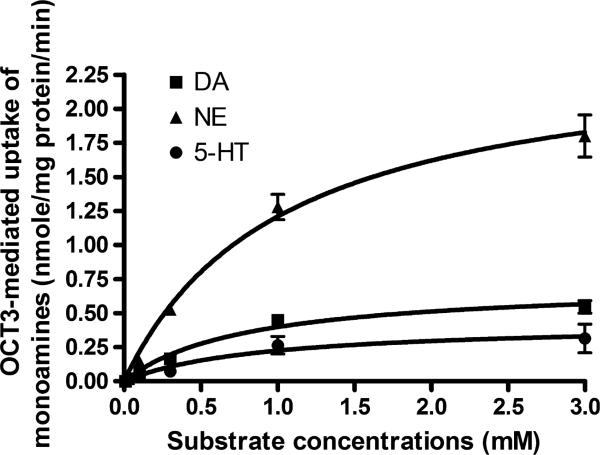

Uptake of neurotransmitters DA, NE, and 5-HT by OCT3

The uptake of DA, NE, and 5-HT (0.01–3 mM) in OCT3 transfected cells were significantly higher than that in vector cells. OCT3-specific uptake was calculated by subtracting the uptake in vector cells from that in OCT3 cells. The data demonstrated that OCT3-mediated DA, NE, and 5-HT uptake was saturable (Fig. 2). The Km values of DA, NE, and 5-HT were determined to be 0.80, 1.03, and 0.90 mM, respectively, while the Vmax values were 0.72, 2.46, and 0.42 nmole/mg protein/min for DA, NE, and 5-HT, respectively. The data suggest that OCT3 is a low affinity and high capacity transporter for the major monoamine neurotransmitters, a finding consistent with previous observations (Grundemann et al. 1998; Wu et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006). The rank of OCT3 transport efficiency towards these three neurotransmitters was determined to be NE > DA > 5-HT based on the ratios of Vmax to Km.

Fig. 2.

OCT3 specific uptake of dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), and serotonin (5-HT). Intracellular accumulation of the neurotransmitters DA, NE, and 5-HT in organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3) and vector transfected cells were determined utilizing an established high-performance liquid chromatography assay. OCT3 specific uptake was calculated by subtracting the uptake in vector cells from that in OCT3 transfected cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

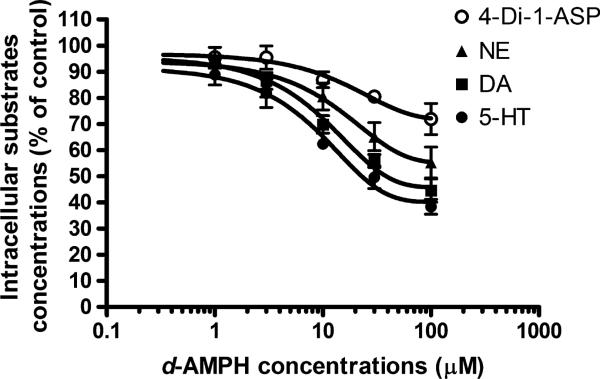

d-AMPH inhibits the uptake of NE, DA, and 5-HT by OCT3

The in vitro inhibition studies showed that d-AMPH inhibited OCT3-mediated uptake of NE, DA, 5-HT as well as the established OCT3 substrate 4-Di-1-ASP in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 3). The IC50 values were determined to be 41.5 ± 7.5 and 24.1 ± 7.0 μM for inhibiting DA and 5-HT uptake, respectively, while a 50% inhibition of NE and 4-Di-1-ASP uptake was not achieved at even the highest assessed concentration of d-AMPH (100 μM).

Fig. 3.

Dextroamphetamine (d-AMPH) inhibition of organic cation transporter 3-mediated transport of dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), serotonin (5-HT), and 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide (4-Di-1-ASP). Organic cation transporter3-mediated uptake of DA, NE, 5-HT, and 4-Di-1-ASP were measured in the absence and presence of various concentrations of d-AMPH. The uptake of the substrates without the treatment of d-AMPH was defined as 100%. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

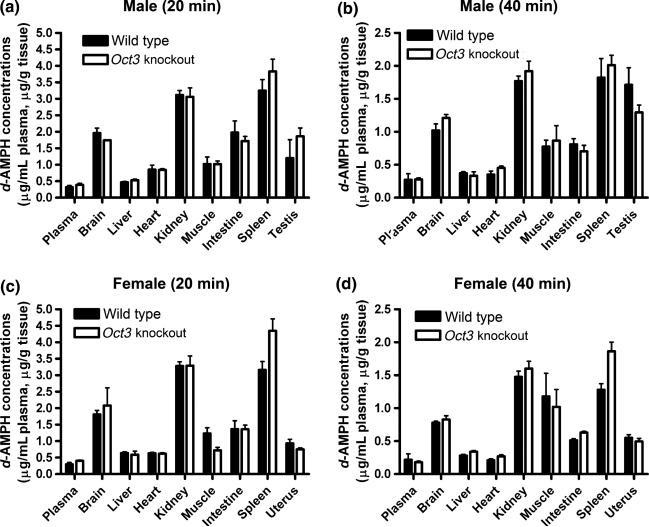

Oct3 knockout and WT mice do not differ in d-AMPH disposition

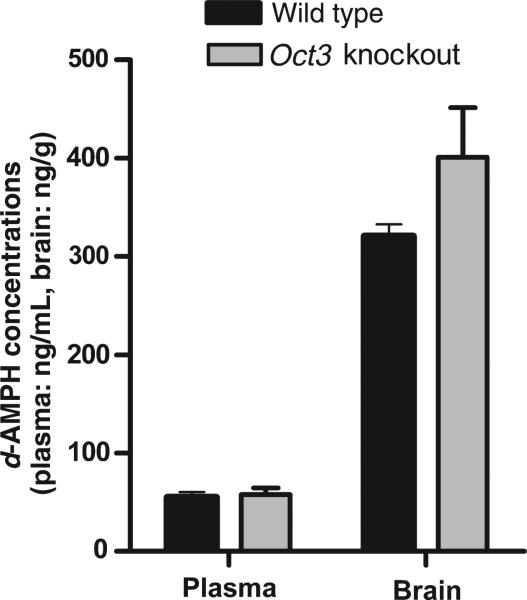

An extensive pharmacokinetic study was conducted to determine d-AMPH concentrations in plasma and the major organs and tissues including the brain, liver, heart, kidney, muscle, intestine, spleen, testis, and uterus in both male and female Oct3 KO and WT mice at 20 and 40 min after i.p. injection with 3.0 mg/kg d-AMPH. The data indicated that d-AMPH concentrations were not significantly different between WT and Oct3 KO mice or between male and female animals (Fig. 4). These data suggest that Oct3 does not affect overall disposition of d-AMPH in those organs and tissues tested. Additionally, the brain and plasma concentrations of d-AMPH in Oct3 KO mice were comparable with that in WT mice after dosing 1.5 mg/kg d-AMPH (Fig. 5), which is consistent with the observation under higher dose (3.0 mg/kg) indicating that the status of OCT3 is unlikely to affect the disposition of d-AMPH in the brain.

Fig. 4.

Pharmacokinetic study of dextroamphetamine (d-AMPH) in Oct3 knockout and wild-type mice. The concentrations of d-AMPH in plasma and the major organs including the brain, liver, heart, kidney, muscle, intestine, spleen, testis, and uterus were analyzed in both male and female Oct3 knockout and wild-type mice at 20 and 40 min after i.p. injection of 3.0 mg/kg d-AMPH. No statistic differences were found between either genotypes or sex. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). OCT3, organic cation transporter 3.

Fig. 5.

Disposition of dextroamphetamine (d-AMPH) in plasma and the brain of Oct3 knockout (KO) and wild-type mice. Plasma and brain concentrations of d-AMPH were measured 30 min post-administration of d-AMPH in Oct3 KO and wild-type males at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg. Each group contains six animals. Both plasma and brain concentrations did not differ between Oct3 KO and wild-type mice. Data are the mean with the error bars presenting the SEM. OCT3, organic cation transporter 3.

Discussion

To date, AMPH has been speculated to be a substrate of OCT3 based on several observations appearing in the biomedical literature. First, AMPH inhibited OCT3-mediated uptake of MPP+ in a concentration dependent manner (Wu et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006). Secondly, the chemical structure of AMPH is markedly similar to that of OCT3 substrates NE and DA. Finally, AMPH is a weak base, and positively charged under normal physiological conditions, which are properties in common with most established OCT3 substrates. Nevertheless, our examination of the available published literature yielded no confirmatory data demonstrating that OCT3 has the capacity of translocating AMPH across the cellular membrane. In the present study, we compared the uptake of d-AMPH in OCT3 transfected cells relative to control cells. The results clearly indicated that the uptake of d-AMPH did not differ between these two cell lines, whereas the intracellular concentrations of the positive controls, OCT3 substrates MPP+ and 4-Di-1-ASP, were approximately 10-fold higher in OCT3 cells relative to control cells. These data suggest that d-AMPH is in fact not an efficient substrate of OCT3.

These in vitro findings found additional support in the form of an in vivo pharmacokinetic study conducted in Oct3 KO mice as well as control animals. It has been reported that a 72% reduction of OCT3 substrate MPP+ concentration was measured in the heart of Oct3 KO mice relative to that in WT controls, due to the lack of the involvement of Oct3-mediated uptake in the heart of KO mice (Zwart et al. 2001). In comparison, the uptake of d-AMPH into the heart of Oct3 KO mice in the present study was found to be comparable with that measured in both males and female WT animals. These findings provide substantial evidence that d-AMPH is unlikely to serve as an efficient substrate of OCT3. The expression and activity of some transporters have been reported to differ between sexes (Klaassen and Aleksunes 2010). In the present studies, the concentrations of d-AMPH in various tissues of both Oct3 KO and WT mice were compared between male and female mice. The data suggest that neither Oct3 nor sex is a factor that influences the disposition of d-AMPH in vivo in any tissue assayed. It has been previously reported that differences in OCT3 substrate specificity may exist between humans and rodents (Amphoux et al. 2006), though most compounds assessed to date serving as rodent Oct3 substrates also serve as human OCT3 substrates. In the present study, experimental results derived from both human OCT3 transfected cells and Oct3 KO mice models indicated that d-AMPH is not a substrate of either human OCT3 or mouse Oct3.

In the present study, OCT3 specific uptake of the neurotransmitters NE, DA, and 5-HT was confirmed through in vitro uptake studies utilizing OCT3 transfected cell lines. The Vmax and Km values of DA, NE, and 5-HT determined by kinetic studies indicate OCT3 is a high capacity and low affinity transporter of these neurotransmitters, an observation in agreement with previous reports (Grundemann et al. 1998, 1999; Wu et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006). The rank order of OCT3 transport efficiency towards these three neurotransmitters was determined to be NE > DA > 5-HT based on the ratios of Vmax to Km, which is likewise in agreement with other published investigations (Grundemann et al. 1998; Amphoux et al. 2006).

Although the affinity of the three monoamines to the OCT3 protein is overall markedly lower than those values generally associated with the specific transporters DAT, norepinephrine transporter, and serotonin transporter (SERT), the importance of OCT3 in regulating neurotransmission has been a subject of interest in recent years. For instance, a recent study showed that the expression of Oct3 was increased in the brains of SERT deficient mice (Baganz et al. 2008). Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the established OCT3 inhibitor decynium-22 diminished 5-HT clearance and exerted antidepressant-like effects in SERT KO mice but not in WT mice. Feng et al. (2005) conducted a brain microdialysis study in freely moving rats and demonstrated that local perfusion of decynium-22 could result in significant increases of extracellular 5-HT concentrations in the medial hypothalamus (Feng et al. 2005). More recently, published data from this same group was able to show that corticosterone, a relatively selective OCT3 inhibitor, potentiated the SERT inhibitor D-fenfluramine induced increases of extracellular 5-HT concentrations in rat brain (Feng et al. 2009). The development of the Oct3 KO mouse provides a useful model to more fully investigate the role of OCT3 in the regulation of neurotransmission in vivo. Vialou et al. (2004) demonstrated that Oct3 deficient mice exhibited an increase of ingestion of hypertonic saline under thirst and salt appetite conditions, as well as abnormal decreases of Fos immunoreactivity induction in the subfornical organ following sodium deprivation. Additionally, alterations in behaviors related to aminergic pathways as well as reduction in the concentrations of monoamine neurotransmitters in several brain regions were observed in Oct3 KO mice (Vialou et al. 2008). Further, Oct3 KO mice displayed a tendency of increased activity, and were significantly less anxious in several behavioral tests relative to WT controls (Wultsch et al. 2009). Behavioral and neurochemical responses to psychostimulants were also determined to significantly differ between Oct3 KO and WT animals (Vialou et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2009). Local perfusion of antisense oligonucleotides against Oct3 significantly decreased the expression of Oct3 in the rat brain, and as a consequence increased the responses to the AMPH derivative methamphetamine on both motor activity and extracellular DA concentrations in both the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex (Kitaichi et al. 2005; Nakayama et al. 2007). In consolidating these data, it would appear that despite its relatively low affinity for these major monoamine neurotransmitters relative to norepinephrine transporter, DAT, and SERT, OCT3 plays an important role in regulating neurotransmission as well as the responses to some psychoactive drugs.

A number of published studies have suggested that AMPH elevates extracellular DA concentrations and exerts its psychostimulant effects via direct blockade of DAT and activation of DAT reverse transport. The findings that OCT3 is a viable DA transporter and its activity could also be inhibited by AMPH generated the hypothesis that the increase in extracellular DA induced by AMPH might be at least in part due to the inhibition of OCT3. To test this hypothesis, we examined the inhibitory effect of d-AMPH on OCT3-mediated uptake of DA as well as other substrates including NE, 5-HT, and 4-Di-1-ASP. The results confirmed that d-AMPH significantly inhibited DA uptake in a concentration dependent manner with an IC50 value of 41.5 ± 7.5 μM. The inhibitory potency is comparable with d-AMPH-induced inhibition of MPP+ uptake previously reported (Wu et al. 1998). Additionally, d-AMPH was determined to be an inhibitor of OCT3-mediated uptake of 5-HT, NE, and 4-Di-1-ASP. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the mechanisms of d-AMPH-induced OCT3 inhibition (e.g. competitive vs. non-competitive). It is noted that the observed inhibitory potency of d-AMPH upon OCT3 is Markedly less than that on DAT. Considering that the concentrations of d-AMPH in the brain are estimated to be within the nanomolar range after administration with a typical dose in humans, the contribution of OCT3 inhibition to d-AMPH-induced extracellular DA elevation appears remote.

The behavioral and neurochemical responses to psychostimulants have been found to differ between Oct3 KO and WT mice. Behavioral tests have revealed that locomotor responses elicited after high-dose AMPH administration are significantly greater in Oct3 KO mice relative to WT controls (Vialou et al. 2008). It is notable that high dose methamphetamine administration also induces increases in extracellular DA concentrations in Oct3 KO mice that are significantly higher than that found in control animals (Cui et al. 2009). Current theory suggests that under normal physiologic conditions, excessive extracellular DA is transported into neuronal cells by the high affinity transporter DAT. However, DAT has been shown to exhibit less transport capacity relative to the high capacity transporter OCT3. Thus, DAT could be saturated when extracellular DA concentrations reach a very high level after the administration of high doses of psychostimulants. Under this situation, OCT3 could play an important role in maintaining neurotransmission homeostasis via transport of released DA into neuronal or extraneuronal cells. Thus, it is suspected that elevated psychostimulant effects observed in Oct3 KO mice are due to the lack of Oct3-mediated extracellular DA reuptake mechanism. The present study addressed the question of whether the enhanced pharmacodynamic responses to d-AMPH which are observed in Oct3 KO mice compared with control animals is due to the achievement of higher CNS concentrations of the psychostimulant. Our pharmacokinetic studies revealed that, brain concentrations of d-AMPH did not differ between these two genotypes. Additionally, similar pharmacokinetic dispositions of d-AMPH were noted in KO and WT mice in all other major organs tested, including the liver, heart, kidney, muscle, intestine, spleen, testis, and uterus. Finally, it was also demonstrated that sex is not a factor affecting d-AMPH disposition in the mice.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated d-AMPH is not an efficient substrate of OCT3. Additionally, OCT3 functional status does not affect the disposition of d-AMPH in vivo. d-AMPH was found to be an inhibitor of OCT3-mediated transport of DA, NE, and 5-HT. However, based upon observed inhibitory potencies, OCT3 inhibition appears unlikely to play a prominent role contributing to d-AMPH-induced increases of extracellular DA levels in the brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by NIH grant 1R01DA022475-01A1.

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Abbreviations used

- AMPH

amphetamine

- DA

dopamine

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- d-AMPH

dextroamphetamine

- 4-Di-1-ASP

4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- 5-HT

serotonin

- KO

knockout

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- NE

norepinephrine

- OCT

organic cation transporter

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

References

- Amphoux A, Vialou V, Drescher E, et al. Differential pharmacological in vitro properties of organic cation transporters and regional distribution in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama N, Takahashi N, Kitaichi K, et al. Association between gene polymorphisms of SLC22A3 and methamphetamine use disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1644–1649. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baganz NL, Horton RE, Calderon AS, et al. Organic cation transporter 3: keeping the brake on extracellular serotonin in serotonin-transporter-deficient mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:18976–18981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800466105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Aras R, Christian WV, et al. The organic cation transporter-3 is a pivotal modulator of neurodegeneration in the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8043–8048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900358106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng N, Mo B, Johnson PL, Orchinik M, Lowry CA, Renner KJ. Local inhibition of organic cation transporters increases extracellular serotonin in the medial hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2005;1063:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng N, Telefont M, Kelly KJ, Orchinik M, Forster GL, Renner KJ, Lowry CA. Local perfusion of corticosterone in the rat medial hypothalamus potentiates D-fenfluramine-induced elevations of extracellular 5-HT concentrations. Horm. Behav. 2009;56:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser PJ, Lowry CA, Orchinik M. Corticosterone-sensitive monoamine transport in the rat dorsomedial hypothalamus: potential role for organic cation transporter 3 in stress-induced modulation of monoaminergic neurotransmission. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:8758–8766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0570-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorboulev V, Ulzheimer JC, Akhoundova A, et al. Cloning and characterization of two human polyspecific organic cation transporters. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:871–881. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundemann D, Schechinger B, Rappold GA, Schomig E. Molecular identification of the corticosterone-sensitive extraneuronal catecholamine transporter. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:349–351. doi: 10.1038/1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundemann D, Liebich G, Kiefer N, Koster S, Schomig E. Selective substrates for non-neuronal monoamine transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag C, Berkels R, Grundemann D, Lazar A, Taubert D, Schomig E. The localisation of the extraneuronal monoamine transporter (EMT) in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaichi K, Fukuda M, Nakayama H, Aoyama N, Ito Y, Fujimoto Y, Takagi K, Hasegawa T. Behavioral changes following antisense oligonucleotide-induced reduction of organic cation transporter-3 in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;382:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Aleksunes LM. Xenobiotic, bile acid, and cholesterol transporters: function and regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010;62:1–96. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H. Polyspecific organic cation transporters: their functions and interactions with drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;25:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H, Schmitt BM, Gorboulev V. Organic cation transporters. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;150:36–90. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H, Lips K, Volk C. Polyspecific organic cation transporters: structure, function, physiological roles, and biopharmaceutical implications. Pharm. Res. 2007;24:1227–1251. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel F, Vetter T, Russ H, Grundemann D, Azevedo I, Koepsell H, Schomig E. Transport of small organic cations in the rat liver. The role of the organic cation transporter OCT1. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;354:320–326. doi: 10.1007/BF00171063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H, Kitaichi K, Ito Y, Hashimoto K, Takagi K, Yokoi T, Ozaki N, Yamamoto T, Hasegawa T. The role of organic cation transporter-3 in methamphetamine disposition and its behavioral response in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1184:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M, Takahashi T, Nagatsu T. A fluorometric determination of N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion, using high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:540–545. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda M, Saito H, Urakami Y, Takano M, Inui K. cDNA cloning and functional expression of a novel rat kidney organic cation transporter. OCT2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;224:500–507. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytting E, Bryan J, Southard M, Audus KL. Low-affinity uptake of the fluorescent organic cation 4-(4-(dimethylamino) styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide (4-Di-1-ASP) in BeWo cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;73:891–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt A, Mossner R, Gossmann A, Fischer IG, Gorboulev V, Murphy DL, Koepsell H, Lesch KP. Organic cation transporter capable of transporting serotonin is up-regulated in serotonin transporter-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003;71:701–709. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005;75:406–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialou V, Amphoux A, Zwart R, Giros B, Gautron S. Organic cation transporter 3 (Slc22a3) is implicated in salt-intake regulation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2846–2851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5147-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialou V, Balasse L, Callebert J, Launay JM, Giros B, Gautron S. Altered aminergic neurotransmission in the brain of organic cation transporter 3-deficient mice. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:1471–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz TJ, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Methamphetamine-induced alterations in monoamine transport: implications for neurotoxicity, neuroprotection and treatment. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl. 1):44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Kekuda R, Huang W, Fei YJ, Leibach FH, Chen J, Conway SJ, Ganapathy V. Identity of the organic cation transporter OCT3 as the extraneuronal monoamine transporter (uptake2) and evidence for the expression of the transporter in the brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32776–32786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wultsch T, Grimberg G, Schmitt A, et al. Decreased anxiety in mice lacking the organic cation transporter 3. J. Neural. Transm. 2009;116:689–697. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu HJ, Wang JS, DeVane CL, Williard RL, Donovan JL, Middaugh LD, Gibson BB, Patrick KS, Markowitz JS. The role of the polymorphic efflux transporter P-glyco-protein on the brain accumulation of d-methylphenidate and d-amphetamine. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006;34:1116–1121. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart R, Verhaagh S, Buitelaar M, Popp-Snijders C, Barlow DP. Impaired activity of the extraneuronal monoamine transporter system known as uptake-2 in Orct3/Slc22a3-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4188–4196. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4188-4196.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.