Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the error in T1-estimates using inversion recovery based T1-mapping due to imperfect inversion, and perform a systematic study of adiabatic inversion pulse designs in order to maximize inversion efficiency for values of transverse relaxation (T2) in the myocardium subject to a peak power constraint.

Methods

The inversion factor for hyperbolic secant (HS) and tangent/hyperbolic tangent (tan/tanh) adiabatic full passage waveforms was calculated using Bloch equations. A brute force search was conducted of design parameters: pulse duration, frequency range, shape parameters, and peak amplitude. A design was selected that maximized the inversion factor over a specified range of amplitude and off-resonance and validated using phantom measurements. Empirical correction for imperfect inversion was performed.

Results

The tan/tanh adiabatic pulse was found to outperform HS designs, and achieve an inversion factor of 0.96 within ±150 Hz over 25% amplitude range with 14.7 μTesla peak amplitude. T1-mapping errors of the selected design due to imperfect inversion was approx. 4% and could be corrected to <1%.

Conclusion

Non-ideal inversion leads to significant errors in inversion recovery based T1-mapping. The inversion efficiency of adiabatic pulses is sensitive to transverse relaxation. The tan/tanh design achieved the best performance subject to the peak amplitude constraint.

Keywords: MRI, adiabatic inversion, T1-mapping, MOLLI

Introduction

T1-mapping in the myocardium provides a means for quantifying and detecting edema and/or fibrosis with elevated T1 [1–5]. Look-Locker methods such as MOLLI [6,7] based on inversion recovery assume an complete idealized inversion. It is generally appreciated that there is considerable spatial variation in transmit field strength (B1+). Even at 1.5T commonly used for cardiac MRI, the variation can be as high as 25%. To mitigate this problem, adiabatic inversion pulses [8–14] are often employed to reduce the sensitivity to B1+ inhomogeneity in cardiac applications such as Gadolinium enhanced imaging [15,16] and parametric mapping. The hyperbolic secant (HS) design [12] has been used extensively and provides excellent inversion homogeneity over a wide range of both B1+ and off-resonances (B0). However, although the inversion is homogeneous, it is not necessarily complete, which has important implications for the accuracy of T1-mapping.

Quantitative measurement of T1 based on inversion recovery leads to more stringent demands on the performance of the inversion. In this paper, the effect of imperfect inversion on T1-measurement accuracy is characterized and we perform a systematic study of the choice of design parameters used in adiabatic inversion pulses. Adiabatic inversion pulses used to mitigate inhomogeneity of transmit B1 field strength do not achieve perfect inversion as a result of transverse relaxation (T2) during the pulse [14]. Shorter duration inversion pulses achieve better inversion but require higher peak power which may not be realizable. The trade-off of peak power versus inversion efficiency for various designs [12] has shown that designs which deliver more constant power achieve a specified inversion at a reduced peak power. However, these studies have not explicitly accounted for transverse relaxation. By incorporating realistic physiological tissue parameters (T1 and T2) into the design, it is possible to choose parameters with improved inversion efficiency for the specified design criteria (i.e., peak voltage, off-resonance bandwidth, and transmit B1 variation).

Imperfect adiabatic inversion is T2-dependent and leads to a T2-dependent error in inversion recovery based T1 estimates. A reduced T2-dependence is achieved as well as improved inversion efficiency by careful choice of design parameters. Empirical correction for imperfect adiabatic inversion may be used to further improve T1-measurement accuracy.

In addition to imperfect inversion, the MOLLI method incurs a number of errors in estimating T1. The use of a Look-Locker correction which is an approximation [6,7] leads to estimates of T1 that are sensitive to the tissue T1 and T2, off-resonance, heart rate, as well as imaging protocol parameters such as the sampling strategy, flip angle, matrix size, and others. The present study relates solely to the contribution of error to the inversion preparation.

Theory

Influence of imperfect inversion

Inversion recovery is widely used for T1-mapping using Look-Locker methods. In applications such as cardiac MR, a modified Look-Locker (MOLLI) method [6,7] uses inversion recovery with multiple single shot images at different inversion times. Pixel-wise parametric mapping is accomplished by performing a curve fit to the multiple inversion time measurements. The original MOLLI paper [6] assumes a 3-parameter model of the form S(ti) = A – B exp(-ti/T1*), where T1* < T1 represents the apparent T1 which is shortened by the influence of imaging RF pulses. The desired T1 is then calculated at each pixel using T1 = T1*(B/A-1), referred to as the Look-Locker correction, originally derived from considering a continuous fast low angle shot (FLASH) gradient echo readout [17, 18]. The Look-Locker correction is used in MOLLI despite the fact that imaging uses non-continuous balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP), which violates the assumption used in the formulation since FLASH is non-coherent steady-state imaging and therefore insensitive to T2 while bSSFP is coherent steady-state imaging and carries significant T2 weighting. This assumption is a key source of error not treated in this paper and is sensitive to variables such as T1 and T2 as described in the literature [6,19,20]. In the prior formulations, a perfect inversion is assumed. The effect of imperfect inversion introduces a further error, which is the subject of this present work.

In Deichmann's [17] original formulation for continuous FLASH imaging, the equation for the recovery of magnetization over time after an ideal inversion is:

| [1] |

with M0* = M0 (T1*/T1) representing the steady state magnetization, and T1* representing the apparent T1 controlling relaxation from the inverted equilibrium magnetization to M0*. This is fit to a 3-parameter model M(t) = A – B exp(-t/T1*) where the coefficients become A = M0* = M0 (T1*/T1) and B = (M0 + M0*) = M0 (1 + T1*/T1). The Look-Locker correction is readily solved as T1/T1* = B/A – 1. With imperfect inversion, Eq [1] may be re-written as

| [2] |

with the inversion factor δ = |Mz/M0| ≤1 with Mz measured at the end of the inversion pulse. In this case, B = (δ M0 + M0*) = M0 (δ + T1*/T1), and the Look-Locker correction becomes T1/T1* = (B/A – 1)/ δ. In other words, if the adiabatic inversion is imperfect, then the Look-Locker correction must include an additional 1/ δ factor or else a significant error in estimated T1 may result. This correction factor is of particular importance when performing T1-mapping in short T2 species, since transverse relaxation causes imperfect inversion.

Correction for imperfect inversion by incorporating an empirical factor relating to the adiabatic inversion pulse is possible. T1-estimates for MOLLI are not typically corrected for the inversion and may be denoted as T1uncorrected = (B/A-1) T1*. The proposed corrected estimate T1corrected = (B/A-1) T1*/ δ is simply scaled by a fixed value of the inversion factor δ, which is calculated at a nominal value of T1 and T2. However, the inversion factor δ = δ (T1,T2) is dependent on both T1 and T2, it is therefore desirable to use an adiabatic design that has better inversion efficiency which will also minimize the sensitivity of the correction to the unknown tissue parameters.

Adiabatic Inversion

Adiabatic pulses may be used to achieve inversion that is fairly independent of the pulse amplitude above a certain threshold. The adiabatic designs considered in this study were the HS [8] and the tan/tanh. The HS may be generalized as the HSn by which flattens the amplitude thereby delivering more constant power. The formulation of the amplitude and phase for the HSn [10,12] is:

| [3] |

| [4] |

where K is a constant that determines the frequency sweep bandwidth, and −1<= t <= 1, τ = 2t/T. The constant β determines the amplitude level at the start and end of the pulse and is typically chosen such that sech(β)=0.1 [10,12]. The phase is calculated by numerical integration of the amplitude envelope and scaled to obtain the desired swept frequency range (±fmax). The HS pulse is denoted as HS1 with n=1. Design parameters for the HSn are the exponent n, duration T, peak amplitude B1max, frequency sweep fmax, and constant β.

The tan/tanh design of the adiabatic full passage pulse is synthesized by concatenating the half passage and reverse half passage waveforms. The amplitude and phase for the reverse half passage may be calculated as [9]:

| [5] |

| [6] |

with 0< t <= T. Design parameters for the tan/tanh are the duration T, peak amplitude B1max, frequency sweep fmax, and constants ζand κ.

Methods

Adiabatic inversion design optimization

The inversion factor was calculated for each adiabatic inversion design using Bloch equations. Optimization was performed by brute force over a range of design parameters. The design space was ±150 Hz and 25% variation in B1 field strength with a peak voltage constraint. The 25% amplitude range at 1.5T in the heart was based on a limited study (n=4) which measured the variation in flip angle at 1.5T using a saturated dual flip angle method [21]. In this study (unpublished), data was acquired using 2 flip angles acquired on separate breath-holds using an adiabatic BIR-4 saturation pulse each heart beat and a GRE EPI (echo train length 8) readout with single excitation per heartbeat. The actual flip angle was always found to be less than the prescribed flip angle, i.e., 25% variation defined as being in the range 0.8–1.0 times the prescribed flip angle. At 3T the variation in transmit flip angle is significantly greater, varying as much as 32 to 63% (n=10) across the LV [22]. The off-resonance variation across the heart may be significant due in large part to the interface between the heart and lung. The maximum deviation of off-resonance frequency variation across the LV at 1.5T was determined to be 83±36 Hz (n=20) in a study (unpublished data) of quality assurance data with analysis approved by the NIH Office of Human Subject Research. Field map measurements were made as a by-product of water fat separated imaging reconstruction using a multi-echo GRE sequence with non-linear least squares reconstruction [23]. The off-resonance variation may be reduced by localized shimming. Since the bSSFP imaging sequence employed in T1-mapping using the MOLLI approach is sensitive to off-resonance frequency (e.g., usable range < ±1/2TR with TR on order of 3 ms), a ±150 Hz requirement for uniform inversion was deemed adequate to not further limit the accuracy due to off-resonance in the heart.

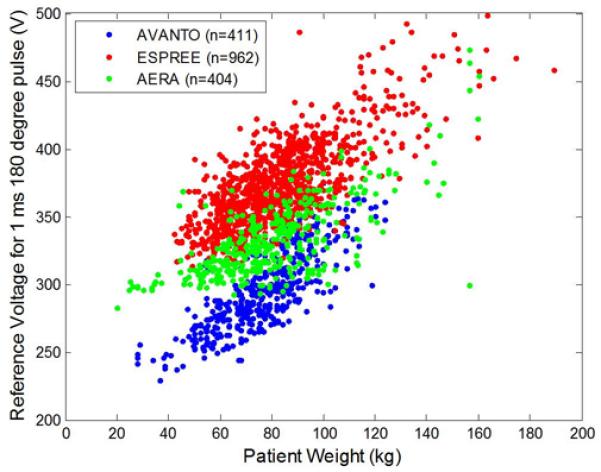

The peak voltage of RF pulses is limited by both amplifier and SAR. In our experience, the amplifier constraint is the dominant limitation for this sequence since the inversion pulse occurs only every few heartbeats. The transmit voltage to achieve a specified B1 field is both system and patient dependent. Figure 1 shows the transmitter reference voltage required to achieve a 180 degree flip angle with a 1 ms pulse, corresponding to a B1 of 11.7 μT. The data was recorded for the purpose of quality control and is plotted for a large number of subjects imaged on 3 different 1.5T scanners with different bore lengths and diameters. This quality assurance data (analysis approved by the NIH Office of Human Subject Research), serves as a reference in selecting a design that will achieve the desired inversion efficiency over a wide range of subject loading. The highest reference voltages were required using the wide, short bore scanner (Siemens Espree, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany); for this model the maximum amplifier voltage was determined to be approximately 650 V which is 1.3 times 500V which was the maximum reference voltage for the heaviest patients with greatest loading. Therefore, a worst case limitation on peak B1 is 1.3×11.7 μT, or approximately 15 μT.

Figure 1.

Transmit amplifier reference voltage as measured by scanner flip angle calibration required to achieve a 180 degree flip angle using a 1 ms square pulse for a range of subject loading for 3 MR systems. These voltages correspond to a 11.7 μT B1+ field.

In view of the demands to achieve ideal inversion for quantitating T1 at low T2's representative of the myocardium, we revisit the performance of various adiabatic inversion pulses. The design considered HSn and tan/tanh pulses over the range T1=400–1600 ms and T2=45–250 ms. Design optimization included the pulse duration, frequency sweep bandwidth, and shape parameters. For each pulse design considered, the inversion factor was calculated for 30 frequencies across ±150 Hz, and 20 B1-field amplitudes between 80–100% of the maximum constraint. The design considered 5 maximum voltages corresponding to 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, and 2 times the reference voltage for a 1 ms 180 pulse equivalent to B1 field strengths of 11.7, 14.7, 17.6, 20.5, and 23.5 μTesla. For hyperbolic secant (HSn) designs, the parameters were: n=1, 2, 4, and 8; duration = 2.56, 5.12, and 10.24 ms; 1-sided frequency sweep fmax = 250 to 5000 Hz in 200 Hz steps; and β = asech(x) in 16 steps, x = 0.005 to 0.08. For tan/tanh designs, the parameters were: duration = 1.28, 2.56, and 5.12 ms; 1-side frequency sweep fmax = 7,000 to 15,000 Hz in 1,000 Hz steps; ζ = 8 to 20 in steps of 2; and tan(κ) from 10 to 30 in steps of 2. The brute force search calculated the inversion factor for 600 amplitude and frequency pairs times 5 peak voltages for each set of parameters. There were 4×3×24×16=4608 HSn designs and 3×9×7×11=2079 tan/tanh designs. Design optimization was performed at the minimum T2 = 45 ms with fixed T1=1000 ms.

Phantom validation

Experimental validation used a set of CuSO4 doped agar gel phantoms with varying concentrations with T1 and T2 in the expected range for myocardium, both native and with Gd contrast. Measurements were acquired using a custom research inversion recovery spin echo (SE) sequence with TR=10s at multiple inversion times (TI) using a 1.5T MAGNETOM Aera Scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany), which enabled test of several inversion pulse designs. The T1 and the inversion factor δ were estimated using a 3-parameter fit, i.e., M(t) = M0 (1 − (1+ δ) exp(-t/T1)), which assumes complete relaxation (TR<<T1) and the inversion factor is denoted by δ. T2 was measured using exponential fit to SE measurements with TR=10s and varying echo times (TE). Transmit field strength was measured using the dual flip angle method [24] to ensure the correct transmit power level, and off-resonance was measured using a multi-echo GRE field mapping sequence to ensure the data were acquired on-resonance.

T1-correction for imperfect inversion

The proposed empirical correction was applied to the spin echo T1-estimate as described below to emulate the Look-Locker correction used in MOLLI without incurring other errors that affect MOLLI, namely the use of bSSFP imaging as well as the influence of successive measurements on previous measurements. In this manner, the error due to imperfect inversion may be separated from the other errors that confound MOLLI. Define the T1 estimate (T1SE) using the SE sequence as the apparent T1 from the 3-parameter fit S(t)=A-B exp(-t/T1SE) since there is negligible influence between measurement using a long TR>>T1. In the case of SE imaging, a Look-Locker correction (B/A-1) as used in MOLLI is unnecessary; for perfect inversion the factor B/A-1 = 1 and for imperfect inversion B/A-1 = δ. However, to calculate the effect of imperfect inversion due to the Look-Locker correction used in MOLLI, the correction (B/A-1) was applied to the apparent T1SE with and without the added empirical correction factor δ. The Look-locker corrected SE estimates which serve as surrogates for the analysis of MOLLI error due to the inversion pulse may be further corrected for the imperfect adiabatic inversion. These estimates were defined as: T1uncorrected = (B/A-1) T1SE and T1corrected = (B/A-1) T1SE/ δ, where δ = δ(T1, T2) was the inversion factor calculated for T1= 1000, and T2 = 45 ms, taken as approximate values for native myocardium. Absolute and percent errors were computed against the relaxation time T1SE as the ground truth.

Results

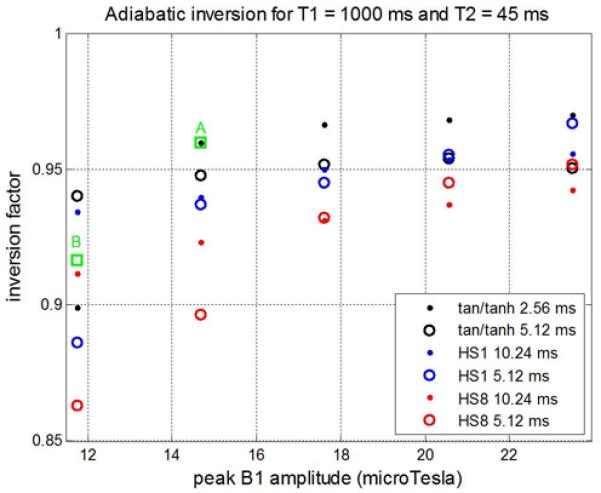

The inversion factor calculated for a variety of designs (Fig 2.) shows that for short T2 = 45 ms, the inversion factor is significantly improved (closer to ideal) for the tan/tanh design with duration 2.56 ms (black dots) than any of the HSn designs for all specified peak B1-amplitudes that are greater than 14 μT. The best HS1 design would require almost twice the peak amplitude to achieve the same inversion factor. The HS1 outperformed the HS8 at this low a value of T2. A tan/tanh design marked by the green box labeled with “A” (fmax=9.5 kHz, ζ=10, tan(κ)=22) was selected since it achieved an inversion factor of 0.96 for 14.7 μTesla which was realizable on all scanners under worst case patient loading conditions (with peak amplitude approx. 25% higher than the reference voltage in Fig 1). The HS1 design marked by the green box labeled with “B” (10.24 ms, fmax=535 Hz, β=3.42) was chosen for experimental comparison since this design was used in an early reported MOLLI implementation [7]. Adiabatic inversion using HS1 designs to produce homogenous inversion over a wide bandwidth and are widely used across many platforms. This specific HS1 with an inversion factor of 0.92 at 11.7 μTesla is used more generally on our system and was designed to a different criteria at a reduced peak amplitude. This HS1 design does not achieve the best inversion factor for the specified design criteria used here, but rather has higher bandwidth.

Figure 2.

Inversion factor vs peak B1 amplitude calculated for various adiabatic inversion pulse designs. Designs marked by green box A and B correspond to the T1-mapping optimized tan/tanh and the HS1 used on the system product sequences, respectively.

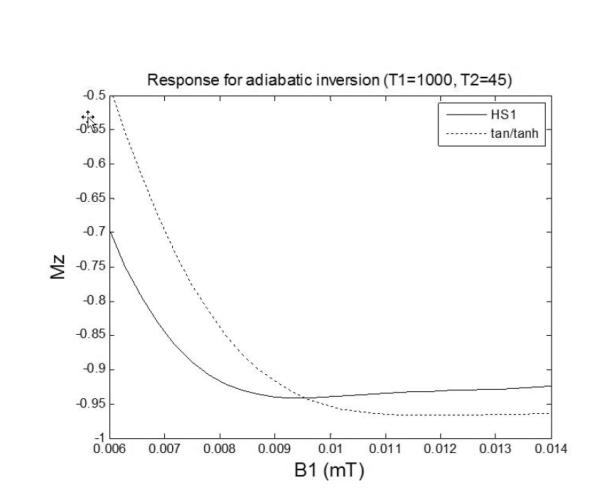

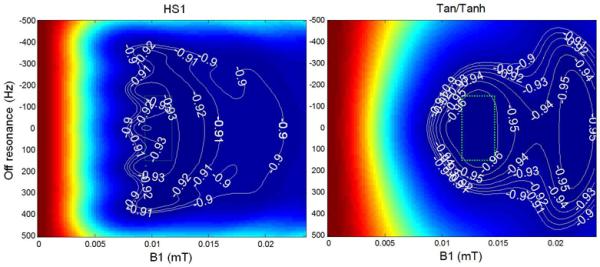

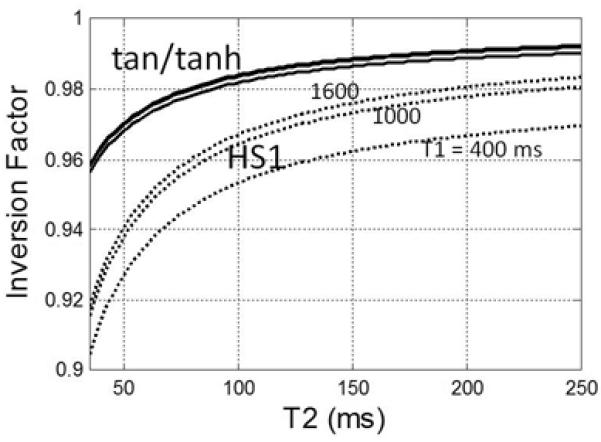

The adiabatic condition achieves independence of B1 transmit field strength but does not achieve perfect inversion (Fig 3) due to T2 relaxation during the pulse, shown for both HS1 design “B” and tan/tanh design “A” on-resonance. The magnetization (Mz) vs. B1 and off-resonance is graphed (Fig 4) for both designs. Note the contours which indicate the inversion factor; the optimized pulse achieves improved inversion over the design region indicated by the dotted green box. The inversion factor δ(T1,T2) is dependent on both T1 and T2 (Fig 5). The tan/tanh design exhibits both higher inversion factor as well as greatly reduced sensitivity to T1 and T2 compared with the HS1 design. For the tan/tanh design “A”, the inversion factor varies from 0.96 to 0.99 over a wide range of T2 from 40–250 ms, with very little variation with T1 from 400–1600 ms, whereas the HS1 design “B” varies considerably with both T1 and T2 (Fig 5).

Figure 3.

Responses of inversion pulse illustrating imperfect inversion due to T2 relaxation.

Figure 4.

Response of adiabatic inversion pulse for T1=1000ms, T2=45ms using HS1 design “B” (left) and tan/tanh (right) design “A”. Design region is indicated by dotted green box (25% amplitude range, ±150 Hz).

Figure 5.

Dependence of adiabatic inversion factor on T2 for 10.24 ms HS1 design “B” (dashed) and 2.56 ms tan/tanh design “A” (solid) designs for T1 = 400, 1000, & 1600 ms. Note that design “A” has both higher inversion factor as well as reduced sensitivity to T1 and T2.

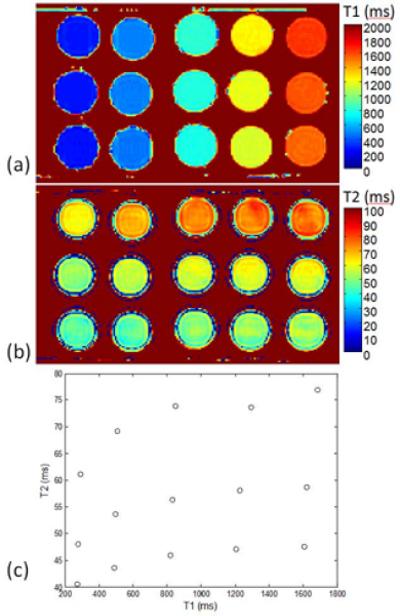

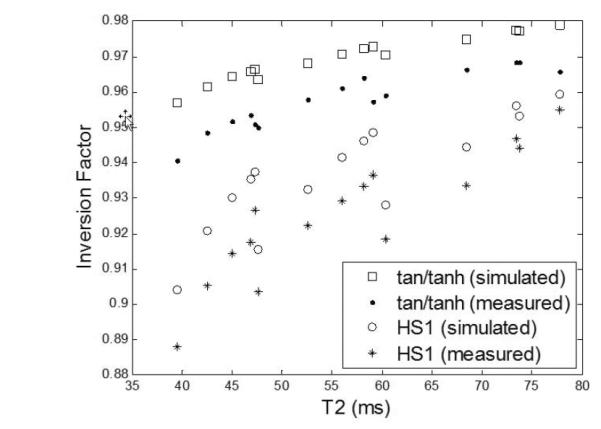

Phantoms were constructed with T1 and T2 in the range expected for myocardium and T1 and T2 were measured using a spin echo sequence (Fig 6). The measured inversion factor based on the 3-parameters fit is greatly improved for the tan/tanh design (Fig. 7) compared with the HS1 reducing the uncorrected error in myocardial T1 from approx. 10% to <5%. Figure 7 graphs both the measured and simulated inversion factors for each phantom where the simulated data is calculated for each phantom using the corresponding measured T1 and T2 (Fig. 6(c)).

Figure 6.

Measurements of phantom T1 and T2: (a) T1-map, (b) T2-map, and (c) T1 and T2 values for each phantom tube.

Figure 7.

Measured and simulated inversion factor vs T2 (various T1) for phantom data using tan/tanh design “A” and HS1 design “B”. Simulated values are calculated based on measured phantom T1 and T2 (Fig. 6(c)).

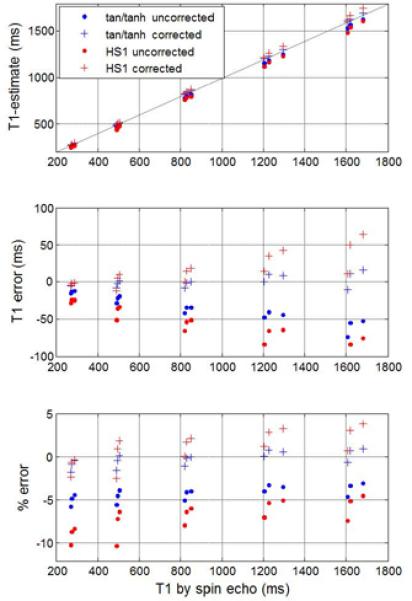

Empirical correction may be applied to T1-maps to reduce the error due to imperfect inversion. The estimated T1 after “Look-Locker” correction vs. true T1 measured by spin echo with and without empirical correction for imperfect inversion for both HS1 and tan/tanh designs (Fig 8) shows that the T2 dependent correction leads to a reduced error for the tan/tanh design. For the tan/tanh pulse design “A”, imperfect inversion leads to a T1-error of approximately 4%, which may be corrected within 1% over the range of T1 and T2 values tested. The HS1 design “B” has an error of approximately 10% and may be corrected to within approximately 3%, leading to overcorrection using this method.

Figure 8.

Estimated T1 after “Look-Locker” correction vs true T1 measured by spin echo with and without empirical correction for imperfect inversion for both the HS1 design “B” and tan/tanh design “A”.

Discussion and Conclusions

Adiabatic inversion pulses are commonly used to achieve homogeneous inversion over a range of transmit field strengths. Imperfect adiabatic inversion results from transverse relaxation (T2) during the pulse and may result in an error in estimates of T1 using inversion recovery methods such as MOLLI [6, 7] or other schemes that assume perfect inversion independent of the method of image readout. T1-mapping error due to imperfect inversion leads to an underestimation of T1 and compounds other sources of error which also tend to underestimate. Underestimation in the MOLLI approach [19,20] generally results from the approximation of the “Look-Locker” correction using SSFP readout with non-continuous readout and is sensitive to tissue T1 and T2, off-resonance, heart rate, and a number of protocol parameters such sampling strategy, flip angle, matrix size, and others. These errors lead to systematic bias errors that range from 5–10% not including the error due to imperfect inversion. The proposed adiabatic pulse design and proposed correction reduces the error by approximately 8% compared to the currently widely used HS design without correction. It improves the reproducibility by reducing the sensitivity of the inversion factor to T1 & T2. There is currently an active discussion over the magnitude of the error and what accuracy is required in order to be clinically useful. Clinical applications [1–4] are emerging which are based on subtle changes in apparent T1 to detect diffuse disease processes both in individuals and population studies. This paper is aimed at improving the overall accuracy and developing a better understanding of an important factor which contributes to the overall error.

The measured values for inversion factor are systematically biased relative to the simulated values (Fig. 7). The measured factors are between 0.014 (T2=40 ms) and 0.009 (T2=80 ms) less than the simulated values for the proposed tan/tanh design “A”, and similarly 0.016 (T2 = 40 ms) and 0.006 (T2 =80) less for the HS1 design “B”. The resulting approximate 1% discrepancy between the measurement and simulation may be due to experimental error or possibly due to the simulation model not accounting for all effects that influence inversion efficiency. While this discrepancy is not fully resolved, the inversion factor of the proposed design is clearly improved by a significant amount compared with the current HS1 design.

A systematic study of the design of adiabatic inversion pulses was undertaken with the goal of reducing the quantitative error in T1-mapping. The inversion efficiency may be improved by using a shorter duration pulse with optimized parameters. Due to peak power constraints, a tan/tanh design was found to achieve better inversion performance than HSn designs. Note that we use the term inversion factor δ (also referred to as inversion number l0 [13]) which is related to inversion efficiency defined as e = ½(1+ δ) in much of the literature on adiabatic pulses [13, 14]. Although it is reported [10–14] that the HS8 has a significant reduction in peak B1 strength relative to the HS1 to achieve a specified inversion factor, this relationship does not account for T2 relaxation during the pulse. For T2 on the order of 45 ms, relaxation has a strong effect on the inversion performance, and leads to a different design choice. This study was limited to design optimization of HSn and tan/tanh pulses with analytic expressions. Numerically optimized pulses [13, 25] might offer further performance improvement.

Reduced dependence on both T1 and T2 facilitate a calibrated empirical correction of T1-estimates to further reduce the T1-error observed during T1-mapping due to imperfect inversion. Although it is possible to estimate the inversion parameter directly in the T1-mapping sequence by acquiring additional images without inversion and performing a 4-parameter fit, this approach requires considerably longer acquisition and further sacrifices precision due to the noise sensitivity with added degrees of freedom [26].

Acknowledgments

Contract Grant Sponsor: NIH/NHLBI Intramural Research Program

References

- 1.Flett AS, Hayward MP, Ashworth MT, et al. Equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the measurement of diffuse myocardial fibrosis: preliminary validation in humans. Circulation. 2010;122(2):138–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broberg CS, Chugh S, Conklin C, Sahn DJ, Jerosch-Herold M. Quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and its association with myocardial dysfunction in congenital heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:727–734. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.842096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schelbert E, Testa SM, Meier CG, et al. Myocardial Extracellular Volume Fraction Measurement by Gadolinium Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Humans: Slow Infusion versus Bolus. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ugander M, Oki AJ, Hsu L-Y, et al. Extracellular Volume Imaging by MRI Provides Insight into Overt and Subclinical Myocardial Pathology. Eur Heart J. 2102;33(10):1268–1278. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellman P, Wilson JR, Xue H, Ugander M, Arai AE. Extracellular volume fraction mapping in the myocardium, Part 1: Evaluation of an automated method. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:63. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S, Higgins DM, Sivananthan MU, Ridgway JP. Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart. Magn Reson Med. 2004 Jul;52(1):141–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messroghli DR, Greiser A, Fröhlich M, Dietz R, Schulz-Menger J. Optimization and validation of a fully-integrated pulse sequence for modified look-locker inversion-recovery (MOLLI) T1 mapping of the heart. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging. 2007;26(4):1081–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver MS. Highly Selective Pi/2 and Pi Pulse Generation. J Magn Res. 1984;59:347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garwood M, Ke Y. Symmetric Pulses to Induce Arbitrary Flip angles with Compensation for RF Inhomogeneity and Resonance Offsets. J Magn Reson. 1991;94:511–525. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tannús A, Garwood M. Improved Performance of Frequency-Swept Pulses Using Offset-Independent Adiabaticity. Journal of Magnetic Resonance A. 1996;120:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannús A, Garwood M. Adiabatic Pulses. NMR in Biomed. 1997;10:423–434. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199712)10:8<423::aid-nbm488>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tesiram YA. Implementation equations for HSn RF pulses. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2010;204(2):333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tesiram YA, Bendall MR. Universal Equations for Linear Adiabatic Pulses and Characterization of Partial Adiabaticity. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2002;156(1):26–40. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2002.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang TL, van Zijl PC, Garwood M. Fast broadband inversion by adiabatic pulses. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1998;133(1):200–3. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonetti OP, Kim RJ, Fieno DS, et al. Cardiac Imaging Technique for the Visualization of Myocardial Infarction. Radiology. 2001;218(1):215–223. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja50215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim RJ, Shah DJ, Judd RM. How We Perform Delayed Enhancement Imaging. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2003;5(3):505–514. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120022267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deichmann R, Haase A. Quantification of Tl Values by SNAPSHOT-FLASH NMR Imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1992;612:608–612. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaptein R, Dijkstra K, Tarr C. A single-scan fourier transform method for measuring spin-lattice relaxation times. J Magn Reson. 1976;24(2):295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gai ND, Stehning C, Nacif M, Bluemke DA. Modified Look-Locker T(1) evaluation using Bloch simulations: Human and phantom validation. Magn Reson Med. 2012 Mar 27; doi: 10.1002/mrm.24251. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24251. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow Kelvin, Flewitt Jacqueline, Pagano Joseph J, Green Jordin D, Friedrich Matthias G, Thompson Richard B. T2-dependent errors in MOLLI T1 values: simulations, phantoms, and in-vivo studies. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2012;14(Suppl 1):P281. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Nayak KS. Saturated double-angle method for rapid B1+ mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1326–33. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung K, Nayak KS. Measurement and characterization of RF nonuniformity over the heart at 3T using body coil transmission. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:643–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernando D, Kellman P, Haldar JP, Liang Z-P. Robust water/fat separation in the presence of large field inhomogeneities using a graph cut algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Jan;63(1):79–90. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stollberger R, Wach P. Imaging of the active B1 field in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1996 Feb;35(2):246–51. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garwood M, DelaBarre L. The return of the frequency sweep: designing adiabatic pulses for contemporary NMR. J Magn Reson. 2001 Dec;153(2):155–77. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodgers CT, Piechnik SK, Delabarre LJ, Van de Moortele PF, Snyder CJ, Neubauer S, Robson MD, Vaughan JT. Inversion recovery at 7 T in the human myocardium: Measurement of T(1), inversion efficiency and B(1) (+) Magn Reson Med. 2012 Nov 29; doi: 10.1002/mrm.24548. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24548. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]