Abstract

Based on the importance of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine (LC-NE) system and the dorsal raphe nucleus-serotonergic (DRN-5-HT) system in stress-related pathologies, additional understanding of brain regions coordinating their activity is of particular interest. One such candidate is the amygdalar complex, and specifically, the central nucleus (CeA), which has been implicated in emotional arousal and is known to send monosynaptic afferent projections to both these regions. Our present data using dual retrograde tract tracing is the first to demonstrate a population of amygdalar neurons that project in a collateralized manner to the LC and DRN, indicating that amygdalar neurons are positioned to coordinately regulate the LC and DRN, and links these brain regions by virtue of a common set of afferents. Further, we have also characterized the phenotype of a population of these collaterally projecting neurons from the amygdala as containing corticotropin releasing factor or dynorphin, two peptides heavily implicated in the stress response. Understanding the co-regulatory influences of this limbic region on 5HT and NE regions may help fill a gap in our knowledge regarding neural circuits impacting these systems and their adaptations in stress.

Keywords: Locus coeruleus, Dorsal Raphe Nucleus, Central Nucleus of the Amygdala, Corticotropin Releasing Factor, Dynorphin

1. Introduction

Mental health disorders are the leading cause of disability in America and Canada (Health, 2008). In a given year 40 million Americans will suffer from an anxiety disorder, 6 million from a panic disorder and 7.7 million from post-traumatic stress disorder (Health, 2008). While there is a large body of work on the neural stress systems, gaps still exist in our knowledge of stress regulation, and the transition from acute stress adaptation to the pathologic consequence of chronic stress. It is known that exposure to stress can predispose individuals to psychiatric and physiological disorders, and the prevalence of these diseases emphasizes the need for a further understanding of stress circuitry.

The noradrenergic nucleus locus coeruleus (LC), a brainstem nucleus that provides the major source of norepinephrine (NE) to the forebrain, is profoundly impacted by stress. Dysregulation of the LC has been implicated in a variety of pathologies including substance abuse, withdrawal, and affective disorders (Aston-Jones et al., 1991; Belujon and Grace, 2011; Kitayama et al., 2008; Knapp et al., 1998; Morilak et al., 2005; Reyes et al., 2008c; Thiele et al., 2000; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Stress and, in particular, the stress-related neuropeptide corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), play a prominent role in the LC, producing a robust change in firing patterns, and altering the neuronal response to subsequent stressors (Bangasser and Valentino, 2012; Reyes et al., 2006; Reyes et al., 2008b). Stress is also known to impact the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), which is enriched with serotonergic (5HT) neurons (DePaoli et al., 1994; Land et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2007; Paredes et al., 2000; Rizvi et al., 1991). Dysregulation of the 5HT system has been demonstrated in affective disorders, and previous studies have shown that DRN is also responsive to both stress and CRF (Heydendael and Jacobson, 2009; Kirby et al., 2000; Van Bockstaele et al., 1993; Waselus et al., 2009). Pharmacological treatment of stress-related affective disorders includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as well as selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), implicating the LC-NE and DRN-5HT systems in putative mechanisms of action (Bandoh et al., 2004; Rovin et al., 2012).

Based on the importance of the LC and DRN in stress-related pathologies, additional understanding of brain regions coordinating their activity is of particular interest. One such candidate is the amygdalar complex. Independent anatomical studies have demonstrated that the LC-NE system and DRN are targeted by amygdalar afferents (Lee et al., 2007; Paredes et al., 2000; Reyes et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2008a; Reyes et al., 2007; Rizvi et al., 1991; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a, 1998b). Specifically, the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) has been shown, in separate studies, to project to these two regions (Peyron et al., 1998; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). These previous findings, in addition to the importance of amygdalar-DRN 5HT and amygdalar-LC NE circuitry in stress responses make the CeA a target for investigation as a source of coordinate regulation of the LC-NE and DRN-5HT systems. Furthermore, the LC-NE and DRN-5HT systems contain receptors for the stress-related neuropeptides corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) and dynorphin (DYN), both of which have been implicated in the neuronal dysregulation associated with affective disorders (Carlezon et al., 2009; Hauger et al., 2009; Risbrough and Stein, 2006; Schwarzer, 2009). While CRF and DYN are becoming increasingly prominent peptides of interest, the mechanisms underlying their involvement in stress pathologies are not well understood.

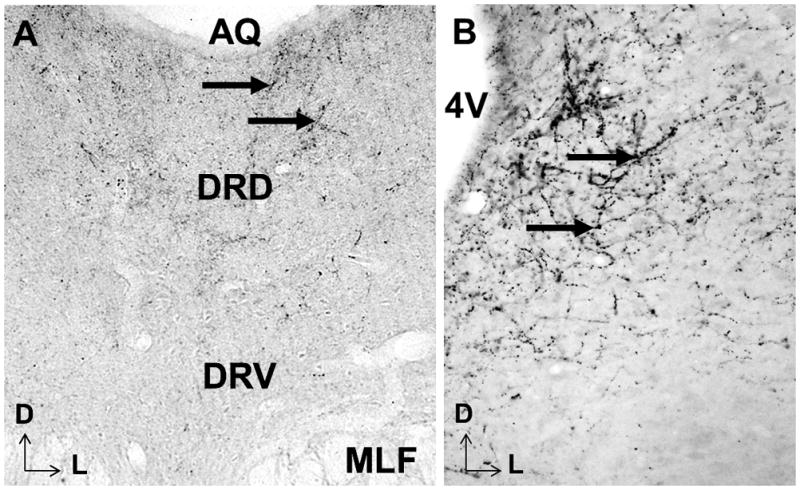

Previous studies have shown that the CeA is enriched with a population of neurons that contain CRF (Cassell and Gray, 1989; Cassell et al., 1986; Gilpin, 2012). These CRF-containing neurons in the CeA project to the LC, and the DRN receives a dense innervation of CRF-containing fibers (Figure 1) (Valentino et al., 2010; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Administration of CRF into the LC or DRN alters neuronal firing patters in a manner similar to the stress response, and results in a re-distribution of CRF receptors (CRFrs) within dendrites (Reyes et al., 2006; Waselus et al., 2009; Waselus et al., 2005). Further, CRFr antagonists have shown efficacy at blocking relapse-like behaviors precipitated by stressful events in alcohol abuse (Baldwin et al., 1991; Lowery and Thiele, 2010; Nielsen et al., 2004). Taken together, CRF is a peptide poised to coordinately influence the NE and 5HT systems.

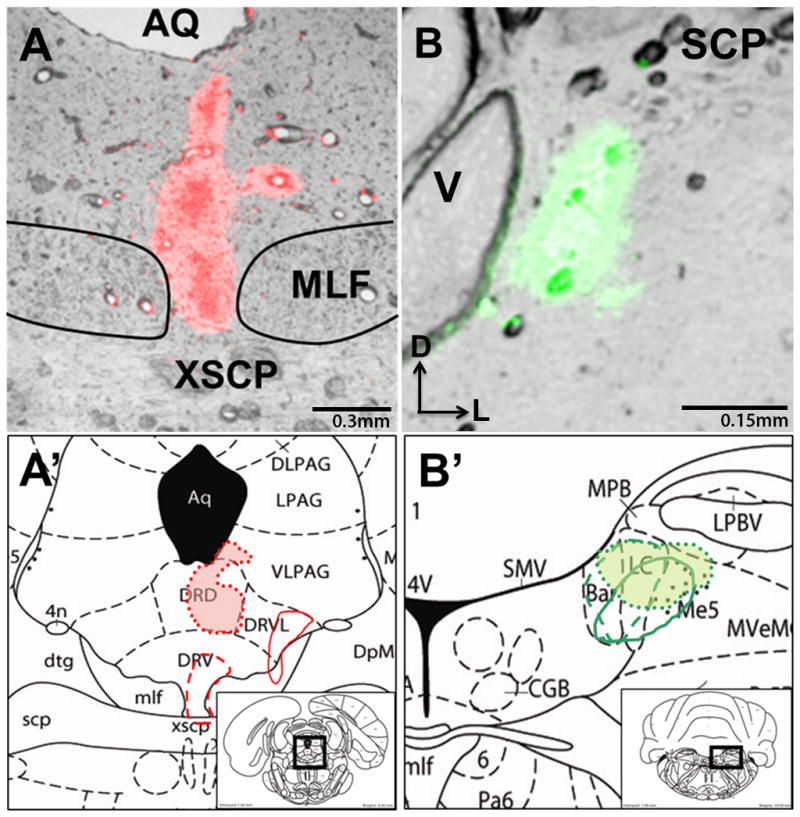

Figure 1.

This photomicrograph illustrates CRF immunoreactive fibers and terminals in the DRN (left) and LC (right), as have been discussed in detail in previous studies (Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Arrowheads point to CRF reactivity as seen by DAB staining. Aq: aqueduct, DRD: dorsal part of the dorsal raphe nucleus, DRV: ventral part of the dorsal raphe nucleus, MLF: medial longitudinal fasciculus, 4V: 4th ventricle

Similarly, DYN, a peptide acting on the kappa opioid receptor (κ-OR), is involved in the stress response and affective disorders (for review see (Knoll and Carlezon, 2010)). For example,κ-OR agonist administration promotes a pro-depressive phenotype in animals, whereas agonists decreased mobility seen in forced swim tests (Carlezon et al., 2006; Carlezon et al., 2009; Nielsen et al., 2004). We have previously shown that DYN efferents from the CeA interact with the LC-CRF system (Reyes et al., 2008c; Reyes et al., 2007), and further, DYN has been previously been established in the DRN as a mediator of the aversive stress response (Land et al., 2009). Thus, it was tempting to speculate that the CeA might be a coordinated limbic source for DYN afferents that project to the LC and DRN.

To examine whether limbic amygdalar afferents send collateralized projections to the DRN and LC, we employed dual retrograde tract-tracing of fluorescent latex microspheres in adult male rats. We found that retrogradely labeled neurons from the LC or DRN were identified within several subregions of the amygdala, as previously described (Peyron et al., 1998; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Here, we show that a population of CeA neurons projects coordinately to both the LC and DRN regions, and that a number of these neurons contain CRF or DYN. These results indicate that amygdalar neurons are positioned to coordinately regulate the LC and DRN systems through collateralized projections, and further, links these brain regions by virtue of a common set of afferents. Considering the importance of the amygdala in stress sensitivity and associating emotional salience with environmental cues, understanding the co-regulatory influences of this limbic region on the LC and DRN, may help fill a gap in our knowledge regarding neural circuits impacting 5HT and NE systems, and their adaptations in affective disorders and stress.

2. Methods

2.1 Retrograde tracing surgery

Male Sprague Dawley rats between 200–300g (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were housed at Thomas Jefferson University in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Animals were kept on a 12h light/dark cycle with temperature at 20° C, and given food and water ad libitum. Rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of a solution containing Ketamine HCl (100mg/kg; Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Inc. St. Joseph, MO) and Xylazine HCl (2mg/kg; Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Inc., St. Joseph, MO) and saline. Animals were placed in a stereotaxic surgical frame (Stoelting Corp., Wood Dale, IL), and prepared for surgery with aseptic techniques. Anesthesia was maintained through the surgery with administration of isoflurane (1–2%, in air; Vedco, St. Joseph, MO) via a specialized nose cone affixed to the incisor bar of the stereotaxic apparatus. Scalp incisions were made and cranial windows were drilled for the injection of fluorescent latex microsphere retrograde tracers (RetroBeads, Lumafluor Corp., Naples, FL) into both the LC and DRN. For these injections, glass micropipettes (Kwik-Fil, 1.2mm outer diameter; World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL) with tip diameters of 15–20 μm were filled with green or red RetroBeads and positioned for injections using coordinates derived from the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1997). For the LC, the nose of the rat was positioned at a 15° angle from horizontal using −10.1mm from bregma, −1.8mm lateral from midline and −7.1mm dorsal from the skull. For the DRN, an alternate color of RetroBead was used with the nose of the rat positioned at an angle of 0° from horizontal using coordinates −7.9mm from bregma, 0.0mm from medial and −6.0mm dorsal from the skull. The RetroBeads were injected unilaterally using a Picospritzer (General Valve Corporation, Fairfield, NJ) at 24–28 psi, and 0.2 Hz with a 10–20 ms duration. After administration of the tracers, the micropipette was left in place an additional 7 minutes to prevent tracer leakage back along the pipette tract. The animals were allowed to recover and housed individually as described for 7 days, an optimal post-surgical survival time as determined in previous papers (Reyes et al., 2011; Waselus et al., 2006). The animals were sacrificed via first deep anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg i.p.; Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Deerfield, IL), then transcardially perfused through the ascending aorta, first with heparin, then with 4% formaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4). The brains were then harvested, notched on the side contralateral to the injections to provide an indication of tissue orientation, and stored in the 4% formaldehyde solution overnight, followed by storage in 20% sucrose solution in 0.1M PB until the brains sank. The brains were then frozen with Tissue Freezing Medium (Triangle Biomedical Science, Durham, NC), and 30μm thick sections were cut through the rostro-caudal extent of the CeA, LC, and DRN to verify injection sites, using a freezing microtome (Micron HM550 Cryostat; Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Every fourth section was mounted on a gelatin coated slide and allowed to air dry before being coverslipped with Fluoromount (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). Tissues from the brains with injection sites restricted to the areas of interest were then processed for further immunohistochemistry.

2.2 Immunohistochemistry

Where further immunohistochemistry was performed, sets of sequential tissue sections through the CeA were placed in 1% sodium borohydride in 0.1M PB for 30 minutes to remove any remaining reactive aldehydes, and sections were then incubated in 0.5% bovine serum albumen (BSA) and 0.25% Trition X-100 in 0.1M Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.6) for 30 minutes. After extensive rinsing in 0.1M TBS, the tissues were incubated overnight in a cocktail of either a rabbit antibody against CRF (generous gift of Dr. W. Vale, Salk Institute, 1:8000), or a guinea pig antibody directed against pro-dynorphin (ppDYN; Neuromics, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) at 1:2000. For immunofluorescence, CRF and ppDYN were then visualized using cyanine dye Cy5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-guinea pig (1:200; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) respectively. Controls were tissues processed in parallel with the omission of either primary antibody.

For light microscopy, sections through the LC or DRN of a naïve rat were processed as has been described previously (Van Bockstaele et al., 1998b; Waselus et al., 2005). Briefly, after overnight incubation in a rabbit antibody against CRF (generous gift of Dr. W. Vale, Salk Institute, 1:8000), sections were incubated in biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit antiserum (1:400, Jackson Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in 0.1% BSA and TBS for 30 minutes. Sections were then washed in TBS and incubated in an avidin-biotin kit (ABC Elite Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes. After additional washes with TBS, sections were placed in 0.02% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-4HCL (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide in TBS for 5–10 minutes. Tissues were then washed extensively in TBS, mounted onto slides, and coverslipped with permount slide mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

The animals used for analysis were those where the retrograde tracer injections were localized to the areas of interest. Images of the injection sites and the distributions of LC and DRN retrogradely labeled neurons in the CeA were obtained with an Olympus BX51 (Tokyo, Japan), and captured with Spot Advanced Software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Sequential sections through the CeA at 120μm intervals were examined and the number of DRN retrogradely labeled cells, LC retrogradely labeled cells, dually retorgradely labeled cells, and cells indicating retrograde labeling in addition to immunoreactivity toward CRF or DYN were counted.

2.3 Quantification of retrograde labeling in the CeA

In animals identified as having the desired placement of neuronal tracers in both the LC and DRN, as evidenced by examining every fourth coronal section cut at 30μm, sections were taken through the extent of the CeA for analysis. Sequential sections were immunolabeled for CRF or DYN. Neuronal projections from the CeA to the LC, DRN, or both simultaneously, in addition to neuronal phenotype, were manually quantified at 60μm intervals from images through the CeA using fluorescence microscopy. Twelve images (six labeled for CRF and six labeled for DYN) were identified from each animal (n=4) that corresponded to similar rostral-caudal levels. The CeA is a subdivision of the amygdalar complex with variable morphology along its rostral-caudal extent that, according to the Paxinos and Watson Rat Brain Atlas (Paxinos, 1997), extends approximately from bregma −1.80 to −3.30mm. Within the CeA, three subdivisions have been identified – medial (CeM), lateral (CeL), and capsular (CeC). To best describe the nature of projections from the CeA to the LC and DRN, retrogradely labeled cells have been quantified as being located in the CeM, CeL, or CeC, based on their location within the CeA at the rostral-caudal level of the section being analyzed.

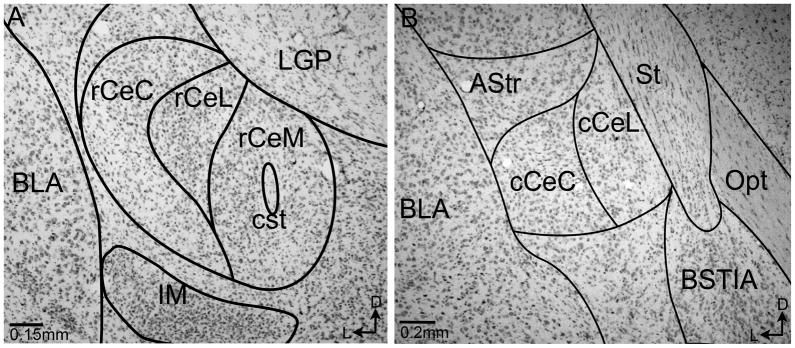

The CeA was then divided into three subgroups based on rostral-caudal morphology: Bregma −1.80 to −2.20mm was denoted as rostral CeA (rCeA) and data was obtained for four (two stained for DYN and two stained for CRF) non-adjacent 30μm sections from each rat, Bregma −2.20 to −3.10mm was denoted as mid-CeA (mCeA) and was comprised of six sections (three CRF and three DYN labeled), and Bregma −3.10 to −3.40mm was denoted as caudal CeA (cCeA) and was comprised of two sections (one DYN and one CRF), matched for CeA morphology across all animals. Representative images of the three rostral-caudal divisions and medial, lateral, and capsular subdivisions can be seen in Figure 3. An example of adjacent tissue sections that were labeled with Nissl stain to assist in delineation of CeA morphological boundaries can be seen in Figure 4. The number of labeled cells per region is presented by average number of cells for all animals ± SEM, or by percentage of total labeled cells for all animals ± SEM, as denoted.

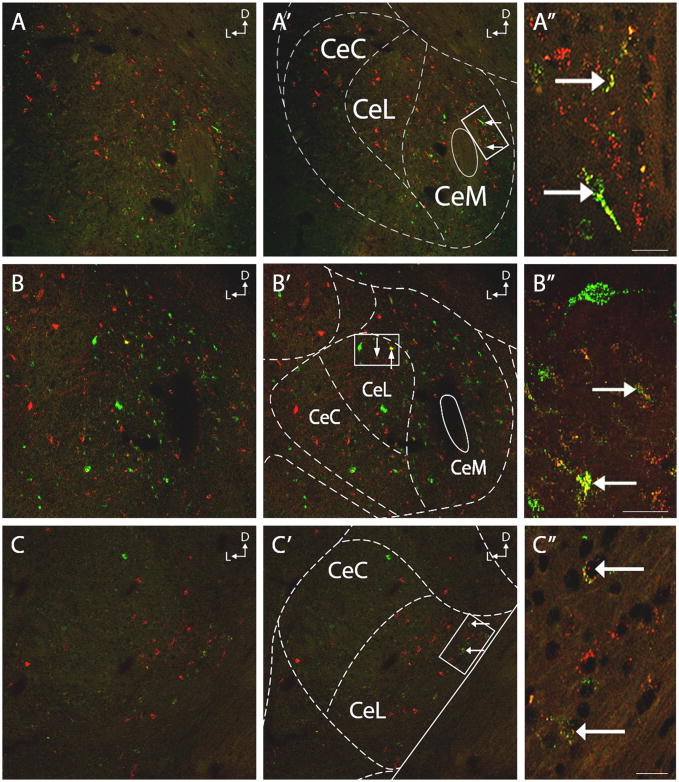

Figure 3.

Images A–C are low magnification representations of the rostral (A), mid (B), and caudal (C) subdivisions of the CeA. A′–C′ feature overlays of the CeA morphology based on the Paxinos and Watson Rat Brain Atlas maps (1997). A/A′ are from Bregma −2.12mm, B/B′ are from Bregma −2.56mm, and C/C′ are from Bregma −3.14mm. A″–C″ are higher magnification images from the boxed areas in A′–C′, highlighting cells that contain retrograde labeling from both the DRN and LC. Coordinately projecting cells were seen thorough the rostral-caudal extent of the CeA, and in all subdivisions. CeC: central nucleus of the amygdala capsular subdivision, CeL: central nucleus of the amygdala lateral subdivision, CeM: central nucleus of the amygdala medial subdivision. Scale bars = 20μm.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections through the CeA adjacent to those used for quantification. Rostral (A) and caudal (B) portions of the CeA are labeled with a Nissl stain and overlayed with the boundaries utilized in this study based on the Paxinos and Watson Rat Brain Atlas maps (1997). CeC: central nucleus of the amygdala capsular subdivision, CeL: central nucleus of the amygdala lateral subdivision, CeM: central nucleus of the amygdala medial subdivision, LGP: lateral globus pallidus, BLA: basolateral nucleus of the amygdala, IM: intercalated amygdaloid nucleus, cst: commissural stria terminalis, BSTIA: Intraamygdalar division of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, Opt: optic tract, AStr: Amygdalostriatal transition area, St: stria terminalis.

3. Results

The use and efficacy of fluorescent latex microspheres (RetroBeads) has been established in previous studies both in our laboratory as well as others (Katz et al., 1984; Reyes et al., 2011; Schofield et al., 2007; Waselus et al., 2006). The combination of red and green RetroBeads is a highly efficient approach for dual tract tracing studies (Schofield et al., 2007). The spread of tracers at the injection sites, or uptake by neurons in neighboring areas is always a consideration in tract tracing studies. However, to eliminate this confound, only animals with injection sites contained within the desired loci as described by Paxinos and Watson (1997), and animals with no observed spread of tracer up the injection tracks were used for analysis. Of 15 animals that received unilateral injections of RetroBeads into both the DRN and LC, four animals had precise injection sites that were selectively positioned within both target regions. The center of each injection was indicated by a large and brightly appearing bolus of RetroBeads and is illustrated in Figure 2. Cases where the injection site excessively encroached on adjacent structures were excluded from analysis. Additionally, cases which showed excessive encroachment along the trajectory of the electrode were not included in analysis. Here, all LC injections are represented as green RetroBeads and all DRN injections are represented as red RetroBeads; however, tracer injection color was reversed in every other rat to ensure that patterns of transport were similar between tracers. Figures 2A and 2B show representative injections into the DRN (2A) or LC (2B) while 2A′ and 2B′ illustrate the injection sites in additional animals in the DRN and LC, respectively.

Figure 2.

Illustration of RetroBead injection sites into the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus. A representative image of an injection into the DRN (A) or LC (B) is presented, along with approximate locations of the other quantified cases, superimposed onto rat brain atlas plates (Paxinos and Watson 1997). A′ represents the DRN injections on plate 50, at Bregma −8.0mm, and B′ represents LC injections on plate 58 at Bregma −10.04mm. Aq: aqueduct, DRD: dorsal part of the dorsal raphe nucleus, DRV: ventral part of the dorsal raphe nucleus, DRVL: dorso-lateral part of the dorsal raphe nucleus, XSCP: decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle, MLF: medial longitudinal fasciculus, SCP: superior cerebellar peduncle, LC: locus coeruleus, Me5: mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus, V: 4th ventricle

3.1 DRN projecting neurons

Injection of RetroBeads into the DRN resulted in the labeling of neurons throughout the CeA (Figure 3). Of the neurons that projected to the DRN, there was some variation in origin within the subdivisions of the CeA, and between rostral-caudal levels. Of the analyzed CeA neurons projecting to the DRN (627 ± 180 SEM), on average, 41.80% ± 3.12% were from the CeM, 31.17% ± 2.70% were from the CeC, and 27.03% ± 2.37% originated in the CeL. When examined by rostro-caudal extent, in the rCeA, out of 252 (252 ± 79) neurons analyzed, 32.77% ± 0.68% were from the CeC, 23.23% ± 2.11% were from the CeL, and 44.00% ± 1.75% originated in the CeM. In the mCeA, out of 332 (332 ± 96) neurons analyzed, 30.44% ± 4.77% were located in the CeC, 22.64% ± 1.77% were located in the CeL, and 46.92% ± 4.16% were located in the CeM. The cCeA is identified as containing only CeL and CeC subdivisions (Paxinos and Watson, 1997), and of the 43 (43 ± 7) DRN projecting neurons found in the cCeA, 27.14% ± 1.90% were found in the CeC, and 72.86% ± 1.89% were found in the CeL.

Following successful detection of retrograde labeling from the DRN in the CeA, tissue sections were immunolabeled for CRF or DYN. Of the DRN-projecting neurons analyzed that were probed for a CRF phenotype (295 ± 82), 16.59% ± 2.35% contained CRF. Of DYN probed DRN neurons (332 ± 98), 18.90% ± 2.47% contained DYN. The CRF and DYN labeling in CeA subdivisions projecting to the DRN is further detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of retrogradely labeled neurons in the subdivisions of the central nucleus of the amygdala containing CRF or DYN.

| Rostral- Caudal Region | Subdivision Analyzed | LC projecting with DYN | LC projecting with CRF | DRN projecting with DYN | DRN projecting with CRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rCeA | CeC | 25.23% ± 5.64% | 19.25% ± 6.98% | 18.65% ± 2.18% | 14.18% ± 5.07% |

| CeL | 16.33% ± 3.97% | 19.13% ± 7.09% | 22.44% ± 4.36% | 13.39% ± 5.60% | |

| CeM | 17.58% ± 5.11% | 10.93% ± 4.36% | 12.18% ± 3.21% | 13.29% ± 1.70% | |

| mCeA | CeC | 40.69% ± 7.45% | 27.90% ± 8.21% | 31.50% ± 9.07% | 17.00% ± 3.50% |

| CeL | 39.16% ± 7.16% | 25.77% ± 9.77% | 23.37% ± 8.20% | 25.20% ± 7.00% | |

| CeM | 19.07% ± 5.46% | 24.81% ± 3.52% | 13.30% ± 2.27% | 12.24% ± 1.60% | |

| cCeA | CeC | 16.42% ± 5.59% | 18.33% ± 10.67% | 6.70% ± 3.88% | 22.88% ± 8.89% |

| CeL | 11.56% ± 6.68% | 13.69% ± 8.27% | 15.21% ± 6.15% | 29.45% ± 13.88% |

3.2 LC-projecting neurons

Of neurons located in the CeA that were labeled by RetroBeads for projections to the LC, a variation in subdivision and between rostral-caudal levels was observed (Figure 3). Of the LC-projecting labeled neurons analyzed (469 ± 124), 37.51% ± 5.21% were from the CeM, 35.38% ± 5.42% were from the CeC, and 27.11% ± 0.82% were from the CeL. Upon examination by rostro-caudal subdivision, in the rCeA, out of 165 (165 ± 49) neurons analyzed 34.13% ± 3.85% originated from the CeC, 40.60% ± 1.62% originated in the CeM, and 25.27% ± 2.36% SEM originated in the CeL. A similar pattern was observed in the mCeA, where of 247 (247 ± 65) neurons analyzed, 34.04% ± 6.41% originated in the CeC, 43.05% ± 6.33% originated in the CeM, and 22.91% ± 1.13% originated in the CeL. In the cCeA, of 57 (57 ± 31) neurons, 46.44% ± 5.15% were projections from the CeC, and 53.56% ± 5.15% were projections from the CeL. Consistent with results of previous studies (Van Bockstaele, Colago et al. 1998; Reyes, Drolet et al. 2008), of the LC-projecting neurons probed for a DYN phenotype (261 ± 69), 26.22% ± 0.59% contained DYN. Of the LC-projecting neurons analyzed (208 ± 63) for a CRF phenotype 22.81% ± 1.74% exhibited CRF immunolabeling. CRF and DYN labeling in LC-projecting neurons in the various CeA subdivisions is further detailed in Table 1.

3.3 Collateralized Projections

Further analysis of the DRN- or LC-projecting neurons showed that a population of CeA cells exhibited retrograde tracers for both regions, indicating a collateralized projection pattern (Figures 3, 5). Out of 132 (132 ± 39) collateralized projection neurons, 57 (57 ± 21) were located in the rCeA, 67 (67 ± 18) were located in the mCeA, and 8 (8 ± 2) were located in the cCeA.

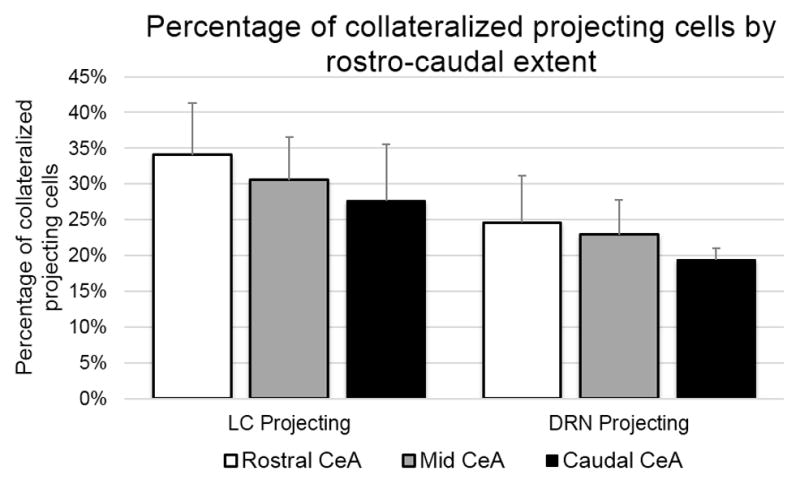

Figure 5.

This chart represents the percentage of collateralized projection cells across the rostral-caudal extent of the CeA. The left portion of this chart represents the percentage of cells labeled for projection from the CeA to the LC that also labeled for projection to the DRN. The right portion of this chart represents the proportion of cells labeled for projection to the DRN that also contained labeling indicative of LC projections. Overall, the LC projecting neurons had a higher percentage of collateralized projections (28.14%) versus those neurons projecting to the DRN (21.05%), and in both cases, the percentage of collateralized projections was decreased in the caudal subdivision.

Of the DRN retrograde labeled neurons, 21.05% (132 ± 39 neurons) also exhibited LC retrograde labeling. There were similar contributions of collateralized cells in the three subregions of the CeA, where, of the DRN projecting neurons that were dually labeled for projections to the LC, 32.30% ± 4.91% were found in the CeC, 39.64% ± 3.89% were found in the CeM, and 28.06% ± 1.59% were found in the CeL.

Analysis of the rostral-caudal subdivisions of the CeA, showed that the average percentage of DRN labeled neurons that exhibited collateralized projections in the rCeA was 25.65% ± 4.43% for the CeC, 28.95% ± 7.01% for the CeL and 22.62% ± 8.45% for the CeM. In the mCeA, 21.53% ± 3.91% neurons labeled for DRN projection were labeled as collateralized projections in the CeC, 22.84% ± 3.02% in the CeL, and 24.29% ± 6.96% in the CeM subdivision. In the cCeA, 24.45% ± 9.15% of CeC cells were labeled as dually projecting, and 17.48% ± 4.83% from the CeL were labeled as dually projecting. The percentages of DRN labeled neurons exhibiting collateralized projections by rostro-caudal subdivision is additionally summarized in Figure 5.

Analysis of LC-projecting neurons showed that 28.14% (132 ± 39 neurons), also exhibited DRN retrograde labeling. There were similar proportions of collateralized cells in the three subregions of the CeA, where, of the LC projecting neurons that were dually labeled for projection to the DRN, 32.30% ± 4.90% were found in the CeC, 28.06% ± 1.59% were found in the CeL, and 39.64% ± 3.89% were found in the CeM.

Analysis of rostral-caudal subdivisions of the CeA showed that the average percentage of LC labeled neurons that exhibited collateralized projections to the DRN in the rCeA was 36.89% ± 8.15% for the CeC, 36.40% ± 6.02% for the CeL and 30.38% ± 8.61% for the CeM. In the mCeA, the CeC had 28.23% ± 6.72% of the LC projecting neurons label for collateralized projection to the DRN, while 31.56% ± 6.42% and 33.16% ± 5.78% of the LC cells were collateralized in the CeL and CeM, respectively. The percentage of LC projecting cells that also exhibited labeling for DRN projection in the cCeC was 22.79% ± 10.14%, while in the cCeL it was 28.35% ± 9.32%. The percentages of LC labeled neurons exhibiting collateralized projections by rostro-caudal subdivision is additionally summarized in Figure 5.

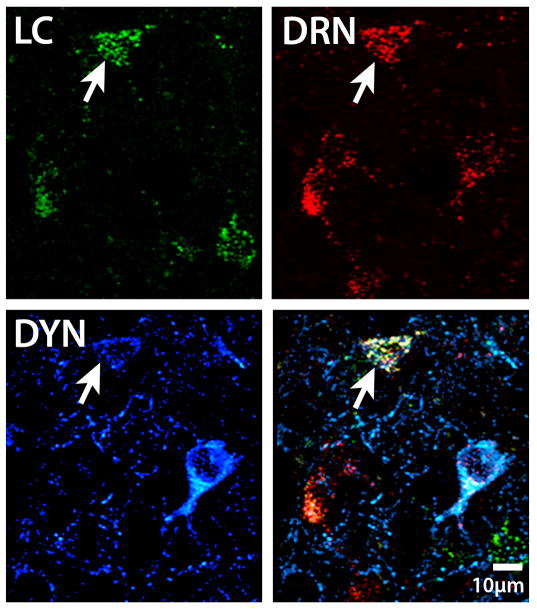

3.3.1 CRF in collateralized projections

Some of the collateralized neurons projecting to the LC and DRN were shown to contain CRF (Figures 6–7). On average, 21.90% ± 2.96% of the total collateralized projecting cells were immunolabeled for CRF, as detailed in Figure 6. In the CeC subdivision, an average of 24.61% ± 6.41% of collateralized cells labeled for CRF, the CeL had CRF labeling in 26.15% ± 7.91% of collateralized neurons and the CeM had CRF labeling in 19.50% ± 3.54%. When CRF labeling of collateralized projecting neurons was examined by rostral-caudal extent, the rCeA had 17.96% ± 5.35% of collateralized cells containing CRF, the mCeA had 23.64% ± 1.60%, and the cCeA had 22.50% ± 13.15%. The percentages of collateralized projection cells containing CRF is further detailed by subdivision and rostro-caudal extent in Figure 6.

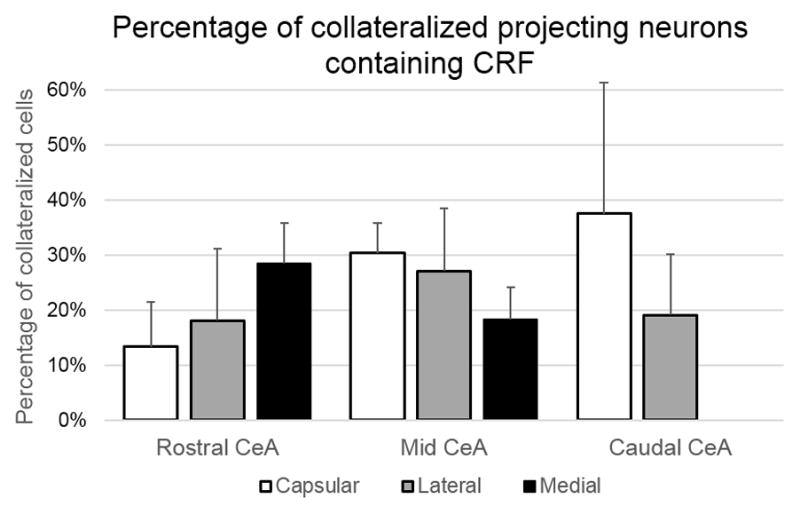

Figure 6.

Of the cells that were retrogradely labeled in the CeA for projection to the LC and DRN simultaneously, a population of these neurons had a CRF phenotype. This chart illustrates the quantitive analysis of the location of collateralized projection neurons containing CRF in the CeA, as an average of distribution percentages ± SEM seen from all animals. The percentage of CRF containing neurons for rostral, mid, and caudal portions of the CeA is further broken down by capsular, lateral, and medial CeA subdivision. Neurons with a CRF phenotype varied in proportion of collateralized projection cells across subdivisions, with a notably higher percentage of CRF collateralizations in the capsular portion of the caudal CeA.

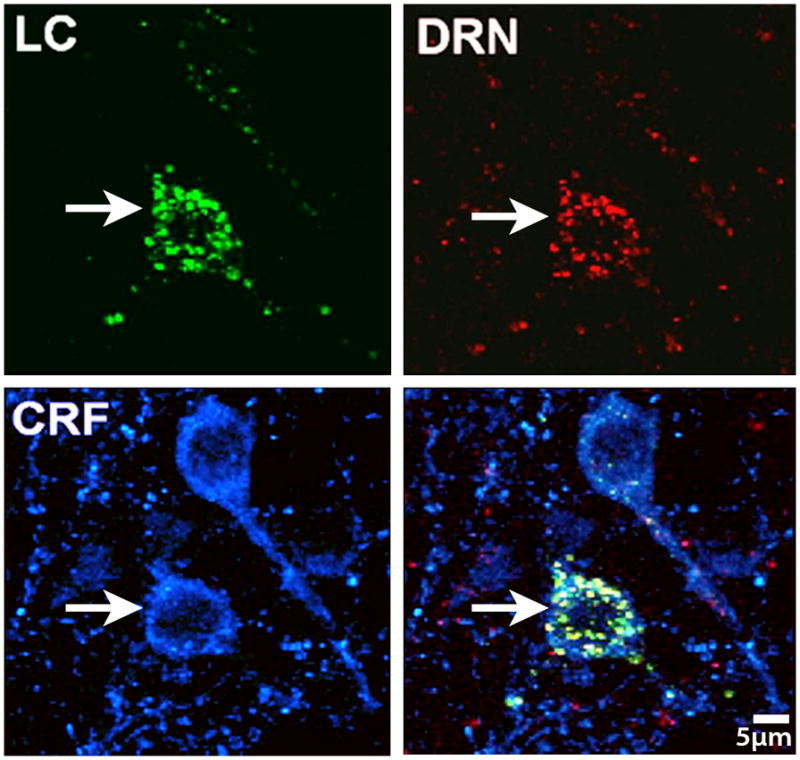

Figure 7.

High magnification image of neurons in the CeA, showing a population that is both dually projecting to the LC (green RetroBead labeling) and DRN (red RetroBead Labeling), as well as CRF containing (cyan). This population of dually labeled amygdalar neurons is poised to coordinately regulate these key stress responsive nuclei, and the presence of CRF in a portion of this population indicates the importance of this peptide in the neural circuits that impact the DRN and LC systems.

3.3.2 DYN in collateralized projections

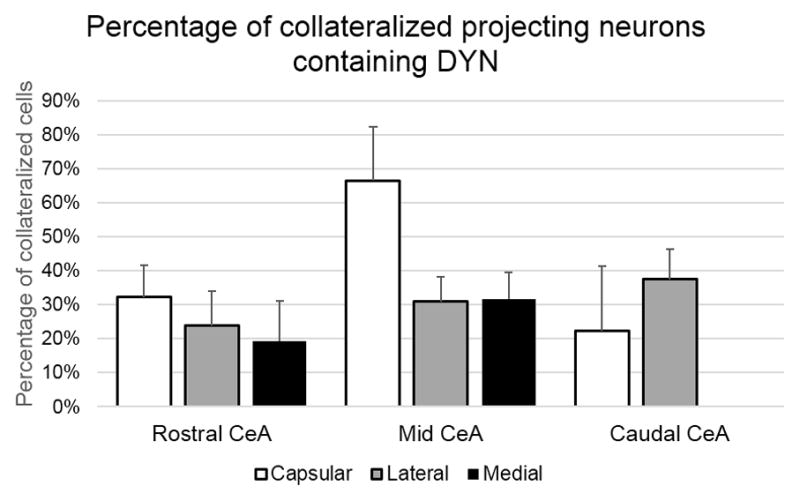

Some of the collateralized neurons projecting to the LC and DRN were shown to contain DYN (Figures 8–9) with, on average, 34.34% ± 4.68% of the total collateralized projections expressing a DYN phenotype. In the CeC subdivision an average of 46.48% ± 10.95% collateralized cells were labeled for DYN, while in the CeL and CeM, 27.26% ± 5.12% and 28.87% ± 8.25% of neurons were labeled for DYN respectively. When examined by rostral-caudal extent, the rCeA had 27.48% ± 3.73% of collateralized cells containing DYN, while the mCeA and the cCeA had 39.59% ± 4.99%, and 37.22% ± 12.81% DYN, respectively. The percentages of collateralized projection cells containing DYN is further detailed by subdivision and rostro-caudal extent in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Of the cells that were retrogradely labeled in the CeA for projection to the LC and DRN coordinately, a population of these neurons had a DYN phenotype. This chart illustrates the quantitive analysis of the location of collateralized projection neurons containing DYN in the CeA, as an average of distribution percentages ± SEM seen from all animals. The percentage of DYN containing neurons for rostral, mid, and caudal portions of the CeA is further broken down by capsular, lateral, and medial CeA subdivision. Neurons with a DYN phenotype made up a roughly similar proportion of dual projecting cells across subdivisions, with the exception of the capsular division of the mid-CeA which contained an increased number. This increase in the mCeA capsular division is in line with an increase in DYN cells in that area as described by previous studies (Fallon and Leslie, 1986).

Figure 9.

DYN was seen in CeA neurons as previously described. In this high magnification image of cells in the CeA, a population of neurons can be seen that is dually projecting to the LC (green RetroBead labeling) and DRN (red RetroBead labeling), as well as contains DYN (cyan). The finding of DYN in dually projecting neurons further implicates DYN as an important peptide that may play a role in the stress response and has an influence over the LC and DRN systems.

4. Discussion

Anatomical studies have shown that the DRN and the LC receive afferents from the amygdala, particularly the CeA (Peyron et al., 1998; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Our present data using dual retrograde tract tracing is the first to demonstrate a common population of amygdalar neurons that project in a collateralized manner to the LC and DRN, indicating that amygdalar neurons are positioned to coordinately regulate the LC and DRN, and links these brain regions by virtue of a common set of afferents. Further, we have also characterized the phenotype of a population of these collaterally projecting neurons from the amygdala as containing CRF or DYN.

4.1 Methodological Considerations

RetroBead labeling from the DRN and LC observed in the present study was consistent with results reported in other studies (Lee et al., 2005; Peyron et al., 1998; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a). The extended amygdala is a large and morphologically varied structure comprised of multiple components with different functions. While it is important to elucidate neural circuits arising from different amygdalar subregions, this study focused on the central nucleus of the amygdala, a region that plays a key role in fear, anxiety, and the stress response, and is a known afferent to the LC.

There exist a variety of approaches for subdividing the CeA. While some previous studies examining neuropeptide distributions in the CeA used the boundaries proposed by Swanson (1998) (Day et al., 1999; Marchant et al., 2007; Swanson and Petrovich, 1998), others have delineated the CeA according to Paxinos and Watson Rat brain Atlas (Fu and Neugebauer, 2008; Lam and Gianoulakis, 2011; Paxinos, 1997; Spannuth et al., 2011). The subdivisions of the CeA presented in the present study follow the delineations of Paxinos and Watson (1997) and are illustrated by overlays in Fig 3, and adjacent Nissl stained sections in Fig 4 (Paxinos, 1997). The use of subdivisions is an important component of data analysis as it provides a context for regional specificity in this large and varied brain region.

4.2 Context within previous neuroanatomical studies

The findings presented here are largely in agreement with previous work detailing connections between the CeA and the LC or DRN (Lee et al., 2005; Paredes et al., 2000; Peyron et al., 1998; Reyes et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2008a; Valentino et al., 2010; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a). Projections from the CeA to the LC have been previously described and the phenotype of limbic afferents to the LC-NE system have been detailed (Aston-Jones et al., 1991; Reyes et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2008a; Reyes et al., 2007; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a; Wallace et al., 1989). While similar to previous studies (Reyes et al., 2011), it is possible that the numbers of neurons with CRF or DYN phenotypes presented here represents an underestimate, as animals in this study were not treated with colchicine, an axonal transport blocker used to increase peptide visualization (Swanson et al., 1983). However, this study is the first to examine CeA projections to the LC and DRN by CeA subregion, and to detail the locations of CRF and DYN CeA neurons projecting to these regions.

A previous study by Lee et al. (2007) used retrograde tracing to examine coordinate projections to the LC core and DRN, finding the preoptic regions and lateral hypothalamus to be of particular influence, with a lack of coordinate labeling in the CeA (Lee et al., 2005). The present study differs from that of Lee and colleagues and this discrepancy may be due to the region targeted for retrograde tracer placement. The nuclear LC core has a restricted set of afferent inputs compared to the peri-LC (Aston-Jones et al., 1986; Shipley et al., 1996). The peri-LC includes LC dendrites extending hundreds of microns from the core, and is known to be targeted by diverse inputs, including the CeA (Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996b, 1998b, a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999). Thus, when considering both sets of findings, there is an important distinction to be made between the lack of coordinate afferent regulation between the CeA and DRN/LC core, and between the robust CeA and DRN/peri-LC regulation observed in the present study. This difference has implications for the functions of the coordinate afferents, and suggests that the peri-LC region serves as an important integrative center influencing LC discharge activity (Van Bockstaele et al., 1998b; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999).

Previous ‘survey’ (where multiple brain regions are examined simultaneously) studies by Peyron et al., Paredes et al., and Rizvi et al. have identified differences in retrograde labeling when tracers were placed in varying regions of the DRN, or periaqueductal gray (PAG) including the DRN (Paredes et al., 2000; Peyron et al., 1998; Rizvi et al., 1991). Our data is in agreement with this work, and indeed there was some variation in the extent of retrograde labeling observed in the CeA depending on the DRN injection site. For the present study, however, the data has been specifically focused on the coordinate projections from the CeA to the LC and DRN regions. As this is a more targeted study, a more detailed examination of the CeA was conducted, compared to previous works examining patterns across many distinct brain regions. Additionally, data presented for retrogradely labeled neurons includes cell counts from a substantially greater area of CeA than has been quantified in several previous survey works (Lee et al., 2005; Paredes et al., 2000; Peyron et al., 1998). Here, we are the first to examine and describe CRF and DYN phenotypes in CeA afferents to the DRN, and to provide an in-depth analysis of projections by rostro-caudal extent and subregion of the CeA.

4.2 Connections between the CeA and LC

The direct anatomical connections between the CeA and LC/peri-LC have been examined in previous studies which showed that the CeA sends afferent projections to the LC/peri-LC which contain CRF and DYN (Cedarbaum and Aghajanian, 1978; Reyes et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2008a; Van Bockstaele et al., 1996a; Wallace et al., 1989). This study was the first to examine the distribution of LC projecting neurons in the CeA across its rostral-caudal extent and by CeA subregion. Overall, findings indicate that while there is not a large distribution change in neurons projecting to the LC between CeA subregions, the highest percentage of LC projecting cells were in the medial subdivision of the CeA. While the functional implications of the subdivisions of the CeA are a source of continued investigation, the CeM has been shown to receive afferent projections from a wide variety of structures, such as the thalamus and frontal cortex, and interestingly, the LC, which indicates the potential for a feedback system between these regions (Bienkowski and Rinaman, 2012; Sah et al., 2003).

4.3 Connections between the CeA and DRN

The connections between the CeA and DRN have been examined in some previous studies; however, gaps still exist in the knowledge of anatomical organization between these areas. For example, fear-potentiated startle increases the marker of neuronal activation, c-fos, in both the CeA and DRN (Spannuth et al., 2011), and cocaine dependence increases CRF immunoreactivity in both these regions (Zorrilla et al., 2012), linking their roles in stress and substance addiction. Additionally, tracing from the CeA indicates afferent connections between the DRN and periaqueductal grey (Bienkowski and Rinaman, 2012; Rizvi et al., 1991), and in some studies involving the sleep systems, activation of the DRN had the effect of inhibiting CeA neurons (Spannuth et al., 2011), indicating the potential for a feedback loop type interaction between these two structures as well. In this study, we have shown direct afferent communication from the CeA to the DRN, and characterized the projections with respect to CeA region. When examined by CeA subdivision, the retrogradely labeled neurons were more prevalent in the CeM, with a difference in subdivisions being the most pronounced in the caudal CeA, where the CeL (the most medial portion of the CeA at that rostral-caudal level) contained 72.86% ± 1.89% of cCeA-DRN projecting neurons. Previous studies have shown that CeM output is implicated in fear conditioning, with CeL cells showing conditioned fear plasticity (Duvarci et al., 2011). This higher proportion of efferents from these regions to the DRN, and as previously discussed the LC, has the potential to play a role in the fear and anxiety circuits between these areas that can eventually lead to psychiatric pathology including PTSD and anxiety induced affective disorders (Hammack et al., 2012; Spannuth et al., 2011).

While the anatomical connections between the CeA and LC or DRN have been discussed, the interplay between these three regions is largely unknown, and the present study begins to elucidate the circuitry underlying the influence of the CeA on the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems. The CeA is well established for its roles in giving salience to emotional cues, and for its role in fear learning. The fact that it sends coordinated projections to the LC-NE system and the DRN system, two areas heavily involved in stress related affective disorders including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, may indicate a new potential target for elucidation of the mechanism behind these pathologies. When examining the distributions of neurons in the CeA that project to the LC, 28.14% were labeled for projection to both the LC and DRN. Additionally, when examined, the distribution of neurons in the CeA that project to the DRN and also coordinately projected to the LC was 21.05%. This difference potentially indicates that CeA may impact both the LC and DRN at a similar magnitude, although the CeA may have a stronger impact on the LC-NE system in the brain.

4.4 The role of CRF and DYN in the collateralized projections

We chose to examine the role of CRF and DYN, two peptides heavily implicated in stress and affective disorders, both of which have previously been shown to localize and colocalize in the CeA, as well as act on the LC and DRN (Land et al., 2009; Reyes et al., 2008a; Valentino et al., 1991). The CeA sends direct CRF innervations to the LC, and the DRN is enriched with CRF containing fibers and CRFrs (Valentino et al., 2010; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001; Van Bockstaele et al., 1998a; Waselus et al., 2009). Additionally, DYN-containing axon terminals originating from the CeA target LC noradrenergic dendrites (Reyes et al., 2008c; Reyes et al., 2007), and in the DRN, DYN has been shown to mediate the aversive stress response (Land et al., 2009). In this study we provide a more in-depth elucidation of the phenotype of limbic efferents as a critical step in defining the integration of neural substrates impacted in affective disorders. Results here indicate that of the coordinately projecting cells, 21.90% were CRF containing (Figures 6–7). This is similar to the number of LC projecting cells that were labeled for CRF (22.81%), which would indicate that CRF has a similar impact on LC cells of DRN collateralized and non-collateralized nature. While the DRN is known to contain CRFrs which are CRF responsive (Waselus et al., 2009), the nature of the CRF projections to the DRN from the CeA has not previously been detailed. Findings here indicate that of the CeA neurons that project to the DRN, on average 16.59% contained CRF, compared to the 21.90% seen in coordinately projecting neurons, indicating that a disproportionate number of DRN projecting cells that contain CRF are part of the coordinately projecting population. This further strengthens the role of amygdalar CRF as an important mediator of LC and DRN projecting cells.

When DYN was visualized, it was observed in 34.34% of the coordinately projecting cell population (Figures 8–9). In contrast, of the LC projecting cells 26.22% contained DYN, while of the DRN projecting cells 18.90% contained DYN. The percentage of DYN containing cells being higher in the coordinately projecting population than in the LC or DRN projecting population would indicate that DYN has a particularly influential role in these cells. It is tempting to speculate, based on previous studies showing κ-OR antagonist administration having anti-depressant and anti-anxiety effects (Mague et al., 2003; Shirayama et al., 2004), that the limbic DYN system may be a new target for coordinate control over the DRN and LC-NE systems. Further, dysregulation of the DYN system at an amygdalar level may be responsible for some of the pathology and downstream dysregulation seen in affective disorders.

5. Conclusion

Overall, the findings here indicate that limbic afferents containing CRF and DYN are poised to co-regulate the monoaminergic nuclei, LC and DRN. Previous findings support the importance of amygdalar-DRN and amygdalar-LC NE circuitry in stress sensitivity, substance abuse, and associating salience with emotional cues in the environment. Thus, understanding the co-regulatory influences of this limbic region on 5HT and NE regions, the DRN and LC, may help fill a gap in our knowledge regarding neural circuits impacting 5HT and NE systems and their adaptations in stress.

Highlights.

Neuroanatomical projections from the CeA to both the LC and DRN were examined.

Tract-tracing studies revealed that the CeA sends collateralized projections to the LC and DRN.

A subset of collateralized neurons exhibited labeling for the neuropeptides CRF and DYN.

Ethical considerations.

The animals used in this study were housed at facilities that are centrally managed by Thomas Jefferson University. The facility is fully accredited by AAALAC, demonstrating compliance with the NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” Furthermore all physical plant construction as well as animal maintenance, husbandry and transportation are in compliance with the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act. All possible considerations were given to use the fewest possible animals for this experiment, and animals were monitored daily for any signs of illness, pain or distress.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DA 009082, and MH 40008 awarded to E.V.B. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Beverly Reyes for her surgical training and assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFRENCES

- Aston-Jones G, Ennis M, Pieribone VA, Nickell WT, Shipley MT. The brain nucleus locus coeruleus: restricted afferent control of a broad efferent network. Science. 1986;234:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.3775363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Shipley MT, Chouvet G, Ennis M, van Bockstaele E, Pieribone V, Shiekhattar R, Akaoka H, Drolet G, Astier B, et al. Afferent regulation of locus coeruleus neurons: anatomy, physiology and pharmacology. Prog Brain Res. 1991;88:47–75. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin HA, Rassnick S, Rivier J, Koob GF, Britton KT. CRF antagonist reverses the “anxiogenic” response to ethanol withdrawal in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;103:227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02244208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandoh T, Hayashi M, Ino K, Takada S, Ushizawa D, Hoshi K. Acute effect of milnacipran on the relationship between the locus coeruleus noradrenergic and dorsal raphe serotonergic neuronal transmitters. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser DA, Valentino RJ. Sex differences in molecular and cellular substrates of stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32:709–723. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9824-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belujon P, Grace AA. Hippocampus, amygdala, and stress: interacting systems that affect susceptibility to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1216:114–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski MS, Rinaman L. Common and distinct neural inputs to the medial central nucleus of the amygdala and anterior ventrolateral bed nucleus of stria terminalis in rats. Brain Struct Funct. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0393-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Beguin C, DiNieri JA, Baumann MH, Richards MR, Todtenkopf MS, Rothman RB, Ma Z, Lee DY, Cohen BM. Depressive-like effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist salvinorin A on behavior and neurochemistry in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:440–447. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Beguin C, Knoll AT, Cohen BM. Kappa-opioid ligands in the study and treatment of mood disorders. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2009;123:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell MD, Gray TS. Morphology of peptide-immunoreactive neurons in the rat central nucleus of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1989;281:320–333. doi: 10.1002/cne.902810212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell MD, Gray TS, Kiss JZ. Neuronal architecture in the rat central nucleus of the amygdala: a cytological, hodological, and immunocytochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 1986;246:478–499. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedarbaum JM, Aghajanian GK. Afferent projections to the rat locus coeruleus as determined by a retrograde tracing technique. J Comp Neurol. 1978;178:1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.901780102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HE, Curran EJ, Watson SJ, Jr, Akil H. Distinct neurochemical populations in the rat central nucleus of the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: evidence for their selective activation by interleukin-1beta. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:113–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaoli AM, Hurley KM, Yasada K, Reisine T, Bell G. Distribution of kappa opioid receptor mRNA in adult mouse brain: an in situ hybridization histochemistry study. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:327–335. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvarci S, Popa D, Pare D. Central amygdala activity during fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2011;31:289–294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Leslie FM. Distribution of dynorphin and enkephalin peptides in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1986;249:293–336. doi: 10.1002/cne.902490302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Neugebauer V. Differential mechanisms of CRF1 and CRF2 receptor functions in the amygdala in pain-related synaptic facilitation and behavior. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3861–3876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0227-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and neuropeptide Y (NPY): effects on inhibitory transmission in central amygdala, and anxiety- & alcohol-related behaviors. Alcohol. 2012;46:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Cooper MA, Lezak KR. Overlapping neurobiology of learned helplessness and conditioned defeat: implications for PTSD and mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauger RL, Risbrough V, Oakley RH, Olivares-Reyes JA, Dautzenberg FM. Role of CRF receptor signaling in stress vulnerability, anxiety, and depression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1179:120–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health, N.I.o.M. The Numbers Count: Mental Disorders in America. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heydendael W, Jacobson L. Glucocorticoid status affects antidepressant regulation of locus coeruleus tyrosine hydroxylase and dorsal raphé tryptophan hydroxylase gene expression. Brain Research. 2009;1288:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Burkhalter A, Dreyer WJ. Fluorescent latex microspheres as a retrograde neuronal marker for in vivo and in vitro studies of visual cortex. Nature. 1984;310:498–500. doi: 10.1038/310498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby LG, Rice KC, Valentino RJ. Effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on neuronal activity in the serotonergic dorsal raphe nucleus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:148–162. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama IT, Otani M, Murase S. Degeneration of the locus ceruleus noradrenergic neurons in the stress-induced depression of rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1148:95–98. doi: 10.1196/annals.1410.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp DJ, Duncan GE, Crews FT, Breese GR. Induction of Fos-like proteins and ultrasonic vocalizations during ethanol withdrawal: further evidence for withdrawal-induced anxiety. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll AT, Carlezon WA., Jr Dynorphin, stress, and depression. Brain Res. 2010;1314:56–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam MP, Gianoulakis C. Effects of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonists on the ethanol-induced increase of dynorphin A1–8 release in the rat central amygdala. Alcohol. 2011;45:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land BB, Bruchas MR, Schattauer S, Giardino WJ, Aita M, Messinger D, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD, Chavkin C. Activation of the kappa opioid receptor in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediates the aversive effects of stress and reinstates drug seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910705106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Eum YJ, Jo SM, Waterhouse BD. Projection patterns from the amygdaloid nuclear complex to subdivisions of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 2007;1143:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Kim MA, Waterhouse BD. Retrograde double-labeling study of common afferent projections to the dorsal raphe and the nuclear core of the locus coeruleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:179–193. doi: 10.1002/cne.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery EG, Thiele TE. Pre-clinical evidence that corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor antagonists are promising targets for pharmacological treatment of alcoholism. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:77–86. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Pliakas AM, Todtenkopf MS, Tomasiewicz HC, Zhang Y, Stevens WC, Jr, Jones RM, Portoghese PS, Carlezon WA., Jr Antidepressant-like effects of kappa-opioid receptor antagonists in the forced swim test in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:323–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant NJ, Densmore VS, Osborne PB. Coexpression of prodynorphin and corticotrophin-releasing hormone in the rat central amygdala: evidence of two distinct endogenous opioid systems in the lateral division. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:702–715. doi: 10.1002/cne.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Barrera G, Echevarria DJ, Garcia AS, Hernandez A, Ma S, Petre CO. Role of brain norepinephrine in the behavioral response to stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1214–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen DM, Carey GJ, Gold LH. Antidepressant-like activity of corticotropin-releasing factor type-1 receptor antagonists in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;499:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes J, Winters RW, Schneiderman N, McCabe PM. Afferents to the central nucleus of the amygdala and functional subdivisions of the periaqueductal gray: neuroanatomical substrates for affective behavior. Brain Res. 2000;887:157–173. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 3. Academic Press, Inc; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Petit JM, Rampon C, Jouvet M, Luppi PH. Forebrain afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing methods. Neuroscience. 1998;82:443–468. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Carvalho AF, Vakharia K, Van Bockstaele EJ. Amygdalar peptidergic circuits regulating noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons: linking limbic and arousal centers. Exp Neurol. 2011;230:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Drolet G, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin and stress-related peptides in rat locus coeruleus: contribution of amygdalar efferents. J Comp Neurol. 2008a;508:663–675. doi: 10.1002/cne.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Fox K, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Agonist-induced internalization of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in noradrenergic neurons of the rat locus coeruleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2991–2998. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Stress-induced intracellular trafficking of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in rat locus coeruleus neurons. Endocrinology. 2008b;149:122–130. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Drolet G, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin and stress-related peptides in rat locus coeruleus: Contribution of amygdalar efferents. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008c;508:663–675. doi: 10.1002/cne.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BAS, Johnson AD, Glaser JD, Commons KG, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin-containing axons directly innervate noradrenergic neurons in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risbrough VB, Stein MB. Role of corticotropin releasing factor in anxiety disorders: a translational research perspective. Hormones and behavior. 2006;50:550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi TA, Ennis M, Behbehani MM, Shipley MT. Connections between the central nucleus of the amygdala and the midbrain periaqueductal gray: topography and reciprocity. J Comp Neurol. 1991;303:121–131. doi: 10.1002/cne.903030111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovin ML, Boss-Williams KA, Alisch RS, Ritchie JC, Weinshenker D, West CH, Weiss JM. Influence of chronic administration of antidepressant drugs on mRNA for galanin, galanin receptors, and tyrosine hydroxylase in catecholaminergic and serotonergic cell-body regions in rat brain. Neuropeptides. 2012;46:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Schofield RM, Sorensen KA, Motts SD. On the use of retrograde tracers for identification of axon collaterals with multiple fluorescent retrograde tracers. Neuroscience. 2007;146:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer C. 30 years of dynorphins--new insights on their functions in neuropsychiatric diseases. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2009;123:353–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley MT, Fu L, Ennis M, Liu WL, Aston-Jones G. Dendrites of locus coeruleus neurons extend preferentially into two pericoerulear zones. J Comp Neurol. 1996;365:56–68. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960129)365:1<56::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Ishida H, Iwata M, Hazama GI, Kawahara R, Duman RS. Stress increases dynorphin immunoreactivity in limbic brain regions and dynorphin antagonism produces antidepressant-like effects. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1258–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spannuth BM, Hale MW, Evans AK, Lukkes JL, Campeau S, Lowry CA. Investigation of a central nucleus of the amygdala/dorsal raphe nucleus serotonergic circuit implicated in fear-potentiated startle. Neuroscience. 2011;179:104–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Petrovich GD. What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Rivier J, Vale WW. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Cubero I, van Dijk G, Mediavilla C, Bernstein IL. Ethanol-induced c-fos expression in catecholamine- and neuropeptide Y-producing neurons in rat brainstem. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:802–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Lucki I, Van Bockstaele E. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the dorsal raphe nucleus: Linking stress coping and addiction. Brain Research. 2010;1314:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis AL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Bajic D, Proudfit H, Valentino RJ. Topographic architecture of stress-related pathways targeting the noradrenergic locus coeruleus. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:273–283. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Biswas A, Pickel VM. Topography of serotonin neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus that send axon collaterals to the rat prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1993;624:188–198. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Chan J, Pickel VM. Input from central nucleus of the amygdala efferents to pericoerulear dendrites, some of which contain tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity. J Neurosci Res. 1996a;45:289–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960801)45:3<289::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor-containing axon terminals synapse onto catecholamine dendrites and may presynaptically modulate other afferents in the rostral pole of the nucleus locus coeruleus in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1996b;364:523–534. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960115)364:3<523::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Valentino RJ. Amygdaloid corticotropin-releasing factor targets locus coeruleus dendrites: substrate for the co-ordination of emotional and cognitive limbs of the stress response. J Neuroendocrinol. 1998a;10:743–757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Valentino RJ. Amygdaloid corticotropin-releasing factor targets locus coeruleus dendrites: substrate for the co-ordination of emotional and cognitive limbs of the stress response. J Neuroendocrinol. 1998b;10:743–757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Peoples J, Valentino RJ. A.E Bennett Research Award. Anatomic basis for differential regulation of the rostrolateral peri-locus coeruleus region by limbic afferents. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DM, Magnuson DJ, Gray TS. The amygdalo-brainstem pathway: selective innervation of dopaminergic, noradrenergic and adrenergic cells in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1989;97:252–258. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90606-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Galvez JP, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Differential projections of dorsal raphe nucleus neurons to the lateral septum and striatum. J Chem Neuroanat. 2006;31:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Nazzaro C, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Stress-induced redistribution of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtypes in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Ultrastructural evidence for a role of gamma-aminobutyric acid in mediating the effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on the rat dorsal raphe serotonin system. J Comp Neurol. 2005;482:155–165. doi: 10.1002/cne.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla EP, Wee S, Zhao Y, Specio S, Boutrel B, Koob GF, Weiss F. Extended access cocaine self-administration differentially activates dorsal raphe and amygdala corticotropin-releasing factor systems in rats. Addict Biol. 2012;17:300–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]