Abstract

Objectives

A large percentage of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have bedtime and sleep disturbances. However, the treatment of these disturbances has been understudied. The purpose of our study was to develop a manualized behavioral parent training (BPT) program for parents of young children with ASD and sleep disturbances and to test the feasibility, fidelity, and initial efficacy of the treatment in a small randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Participants and methods

Parents of a sample of 40 young children diagnosed with ASD with an average age of 3.5 years were enrolled in our study. Participants were randomized to either the BPT program group or a comparison group who were given nonsleep-related parent education. Each was individually administered a 5-session program delivered over the 8-week study. Outcome measures of feasibility, fidelity, and efficacy were collected at weeks 4 and 8 after the baseline time point. Children’s sleep was assessed by parent report and objectively by actigraphy.

Results

Of the 20 participants in each group, data were available for 15 participants randomized to BPT and 18 participants randomized to the comparison condition. Results supported the feasibility of the manualized parent training program and the comparison program. Treatment fidelity was high for both groups. The BPT program group significantly improved more than the comparison group based on the primary sleep outcome of parent report. There were no objective changes in sleep detected by actigraphy.

Conclusions

Our study is one of few RCTs of a BPT program to specifically target sleep disturbances in a well-characterized sample of young children with ASD and to demonstrate the feasibility of the approach. Initial efficacy favored the BPT program over the comparison group and suggested that this manualized parent training approach is worthy of further examination of the efficacy within a larger RCT.

Keywords: Sleep, sleep disturbances, sleep problems, bedtime problems, autism, autism spectrum disorders, parent training, Modified Simonds and Parraga Sleep Questionnaire, actigraphy, randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), characterized by deficits in the development of communication and social behaviors as well as the presence of restricted and stereotyped patterns of behavior, often present with considerable sleep problems [1-4]. Based primarily on parent-completed measures, 44% to 83% of children with ASD experience some type of sleep problem, and this finding is regardless of cognitive functioning levels [2,5-12]. The most frequently identified sleep problems primarily are dyssomnias, including delayed sleep onset, difficulty maintaining sleep with night awakenings, early morning awakening, and decreased total sleep time (TST), as well as bedtime resistance and difficulties with sleep associations [11]. In addition to parent-completed measures, a few studies also have included actigraphy as an objective assessment to measure children’s sleep patterns. Actigraphy is a reliable objective method for measuring sleep-wake patterns, including timing, continuity, and sleep duration, which can be used in the home. Although actigraphy data and parent-completed questionnaires have not always been consistent, actigraphy data have reflected sleep disturbances in children with ASD, particularly when compared to their typically developing counterparts [13-15].

The past 50 years of sleep research have demonstrated the essential need for adequate sleep. Sleep plays a significant role in early maturational processes and is considered a critical activity of the brain in the early years of maturation [16-18]. With evidence of the relationship between sleep and learning and memory in humans coupled with animal research, there is strong evidence that sleep plays a vital role in enhancing brain plasticity [19-23]. A lack of adequate sleep has been shown to adversely impact cognitive functions (i.e., memory consolidation, learning acquisition, attention, executive functioning, brain maturation) [18,19,22-26], as well as daytime behavioral adjustment, and temperament regulation [26-28]. Improving sleep is a priority and perhaps more so in young children with ASD in whom development has already been compromised. In view of the detrimental effects of inadequate sleep on cognitive and daytime behavioral adjustment, addressing sleep disturbances early in life is imperative for these children to maximally benefit from therapies targeting core deficits of ASD. Moreover, improving young children’s sleep has the potential to decrease parental stress and improve family functioning.

In light of the lack of safety and efficacy data associated with the use of medication to address sleep problems in young children [29], behavioral interventions for sleep disturbances have been more broadly recommended in pediatrics [30]. However, the behavioral treatment literature specific to sleep and bedtime problems in children with ASD has primarily been limited to small-case or single-subject design studies. These interventions have borrowed from those demonstrated in general pediatrics but with adaptations for those with ASD and other developmental disorders and include establishment of routines, environmental modifications, sleep restriction, extinction and reinforcement procedures, and scheduled awakenings.

These single-subject studies have paved the way for the next level of empirical testing, as outlined in guidelines developed by a National Institute of Mental Health work group, recommending the need for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [31].

There have been a few exceptions to the single-subject studies. These exceptions include an earlier study conducted on an inpatient unit that evaluated the use of a faded bedtime with response cost protocol to target bedtime resistance, delayed sleep onset, and night and early morning awakenings in 14 participants between the ages of 4 and 14 years [32]. Five of these participants had ASD. Outcomes included sleep diary data and direct observation data, as the study was completed on an inpatient unit. Wiggs and Stores [33] and Montgomery et al [34] published 2 small RCTs of children with various disabilities, including some children with ASD. The first study included 7 out of 30 children with ASD [33] and the second larger study included 21 children out of a total of 66 participants with ASD [34]. The behavioral parent training (BPT) intervention was developed and evaluated in the first RCT against a waitlist control group [33]. Improvements in this study were seen in the BPT intervention, based on the parent-completed sleep questionnaire but not on actigraphy variables. BPT was then evaluated in a RCT by Montgomery et al [34]; in this study, BPT was compared to either a control group or a “bibliotherapy” approach in which parents were provided education materials to read independently. Children in both treatment groups improved based on parent-completed questionnaire. Actigraphy was not used in this study. A major shortcoming of these RCTs was the variability of disabilities and the lack of specificity by which these disabilities were diagnosed.

More recently, a 5-session parent sleep education program by Reed et al [35] was delivered to small groups of 3 to 5 families (a total of 20 families participated) to improve sleep in children ages 3 to 10 years with ASD. This parent sleep education program provided a chance for individualized input from a parent educator and demonstrated improvements on both parent-completed questionnaires and actigraphy, but this study did not include a control group. In the most recent study to our knowledge, Cortesi et al [36] conducted a study of children ages 4 to 10 years with ASD comparing the efficacy of a 4-session BPT plus melatonin, BPT alone, melatonin alone, and placebo. The behavioral intervention was modeled after 2 earlier studies [34,37]. In this large 12-week RCT (N=134), significant improvements were seen with the use of melatonin, behavioral treatment, and combined treatment with a trend towards the combined group being superior. Outcomes included both a parent-completed sleep questionnaire and actigraphy. The study included a parent-reported measure of adherence asking parents how often they used the behavioral procedures. Participants were required to maintain at least an 80% compliance rate for implementing the behavioral treatment and administration of the pills to continue in the trial. None of the above studies included a measure of treatment integrity of the delivery of the intervention.

Our study aimed to forward this line of inquiry and is in keeping with the model already mentioned on the development of manualized psychosocial interventions in ASD [31]. After developing a manualized BPT program, we conducted a small RCT to test the feasibility and fidelity of the treatment, parent satisfaction, and initial efficacy for young children with ASD and co-occurring sleep disturbances. Therefore, our project was seen as a second step in this process prior to launching a more definitive test of efficacy. In our study, the BPT program was compared to a psychoeducational program (PE) of equal intensity to control for time and attention.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and all participating parents provided informed consent prior to study enrollment. Following treatment development, we conducted an 8-week initial RCT of a parent training program to target sleep disturbances compared to a PE program. Outcome measures were administered at baseline, week 4, and week 8. Measures included parent-report questionnaires and actigraphy.

2.2. Participants

Forty-seven families with a young child between the ages of 2 to 6 years with ASD and at least one sleep disturbance were screened for our study. Forty met eligibility criteria at time of the screening and were enrolled and randomized. Participants primarily were recruited from the clinical services of the Autism Center/Child Development Unit of Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. Children were included in the study regardless of intellectual functioning level. Diagnoses were established by a licensed psychologist with more than 20 years of experience in the field based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV Text Revision [38] criteria and corroborated by both the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised Version (ADI-R) [39] and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) [40]. For purposes of our study, sleep disturbance was defined as the presence of one or more of the following and as occurring 5 or more nights per week: 1) bedtime resistance problems (the child resisted going to bed or displayed disruptive behaviors at bedtime), 2) delayed sleep onset (sleep-onset delay of one hour or more and whether or not the parent was disturbed during that time); 3) sleep association problems (the child fell asleep in a location other than his or her bed and was not acceptable to the parents); 4) nighttime awakenings (the child disturbed the parent or entered into the parent’s room during the night); or 5) morning awakenings (child’s final wakeup time was before 5:00 AM and the child disturbed the parent or entered into the parent room). Children were excluded if there was a question of sleep-disordered breathing, restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, or a circadian-based sleep disorder based on our screening assessment, given that these children could warrant a different treatment not offered in this protocol. If there was a question of one of these disorders, a child was first referred to the Sleep Medicine Clinic for a further assessment to rule out these disorders.

Children with medical diagnoses associated with sleep disturbances also were excluded in addition to children who were assessed as requiring other or more intensive intervention (e.g., inpatient psychiatric services). No children on psychotropic medications, medications or supplements for sleep, or medications that had sedating effects were included. Participants were equally randomized into either the BPT or the PE program group using a block randomization scheme with a block size of 10. For those randomized to the PE group, all participants were invited to participate in the BPT once completing PE program.

2.3. Procedures

Following an initial screening visit to determine study eligibility, a baseline home visit was scheduled to provide instruction on the use of the actigraph device and to assess the sleep environment to individualize treatment. Each parent participant in the 2 groups attended 5 individually administered sessions with a trained therapist. Sessions were delivered in 60 to 90 minutes in a clinic setting. Therapists for both groups were master-trained doctoral students or a senior doctoral–trained behavior analyst. Two of the 3 therapists were board certified behavior analysts by the nationally recognized Behavior Analyst Certification Board. The third therapist was supervised by the senior psychologist/behavior analyst towards eligibility as a certified behavior analyst. Prior to taking a randomized trial case, the therapists either had completed a training case or had shadowed a therapist. Therapists were regularly observed by the study investigator and provided feedback.

2.4. Subject characterization measures

2.4.1. Autism Diagnostic Interview revised version

The ADI-R [39] is a structured interview covering developmental and behavioral aspects of autism. It is administered to the child’s caregiver. Diagnostic assignment is made following an algorithm keyed into Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV Text Revision criteria for autism. The ADI-R also provides a dimensional measure of severity of autistic symptomatology.

2.4.2. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule

The ADOS [40] is an investigator-based assessment that places the child in naturalistic social situations demanding specific social and communication responses. Although the protocol follows standard administration, the situations themselves are unstructured. Thus the ADOS provides a sample of the child’s behavior in a naturalistic setting. Behaviors are coded in the areas of social communication, social relatedness, play and imagination, and repetitive behaviors. The ADOS was administered by research-trained clinicians. This measure was used to corroborate clinical diagnosis.

2.4.3. Cognitive assessment

Depending on the age and functioning level of the child, the abbreviated battery of the Stanford Binet Intelligence Scales fifth edition [41] or the Mullen Scales of Early Learning AGS edition was administered for characterization of the sample [42].

2.5. Outcome measures

2.5.1. Treatment fidelity checklist

Treatment fidelity was defined by 2 components: the treatment integrity (delivery of treatment as intended) and parent adherence to the delivered treatment. Following Waltz et al [43], all sessions were videotaped. For both the BPT and PE programs, each session had an accompanying treatment fidelity checklist with the session integrity and parent adherence goals. These checklists contained the essential elements of each session and were completed by therapists during each session. Behavior therapists rate themselves on this checklist on a scale of 0 to 2 for the goals (0=goal was not achieved, 1=goal was partially achieved, and 2=goal was fully achieved). In addition to the ratings, the therapist provided written comments on any ratings of 0. The score for each session was expressed as a percentage derived from the sum of scores across all items (5–7 items/session) divided by the total possible score ×100. These checklists were modeled after previous work by the first author [44]. Several items also were included in the checklists, assessing parent adherence (e.g., completion of homework, implementation of recommended strategies) and understanding of session materials through responses to activity sheets. A random sample of 10% of each therapist’s videotaped sessions was examined quarterly for interrater reliability of session integrity and parent adherence by an independent observer.

2.5.2. Parent Satisfaction

The Parent Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ) used for our study was modified from the questionnaire developed by the Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network [45]. The questionnaire asked parents to rate the quality of various elements of either the BPT or PE program and was completed at the end of the programs. Items included the number and length of sessions, the usefulness of the teaching tools such as video vignettes, in-session worksheets and homework, and the helpfulness of specific elements of the 2 programs. Items were scored on either 3- or 4-point Likert scales, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of satisfaction with the respective programs. Total percentage scores were then calculated for BPT and PE.

2.5.3. Composite Sleep Index of the Modified Simonds and Parraga Sleep Questionnaire

The modified version of the Simond and Parraga Sleep Questionnaire (MSPSQ) [4,46-48] was completed by the child’s primary caregivers at baseline and at weeks 4 and 8 for both groups. We used earlier-described conventions for determining the Composite Sleep Index (CSI) score [33]. The CSI was calculated by assigning a score to the frequency of targeted sleep problems: bedtime resistance (item 5), night awakening (item 10), early awakening (item 51), and sleeping in places other than bed (item 35). In addition, scores were assigned for the duration of sleep latency (SL) (item 6) and night awakenings (item 12). For frequency, a score of 1 was assigned for problems occurring once or twice a week, while a score of 2 was assigned for problems occurring more than several times a week. For duration, SL lasting up to one hour was scored as 1 and over one hour was scored as 2. For night awakenings, those lasting a few minutes were assigned a score of 1 but given a score of 2 if they lasted longer. Hence, the total CSI score ranged from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating more severe bedtime and sleep patterns.

2.5.4 Actigraphy

Each child was required to wear an actigraph to collect activity data for 5 consecutive weeknights at the 3 time points (baseline, week 4, and week 8). The Motionlogger model actigraph by Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc. (www.ambulatory-monitoring.com) was used in our study. The processor in the actigraph sampled physical motion and translated it to numerical digital data. Actigraphy variables calculated included TST, sleep efficiency (SE) (defined as the percentage of time sleeping while in bed and lights off), and SL (defined by time from lights off to sleep onset). In keeping with convention, we used a standardized calendar-style weekly sleep diary [1].The sleep diary served to ensure the functioning of the actigraph, as the sleep diary has been demonstrated to be critical for monitoring actigraphy artifacts and malfunctions [49]. Although it was not used as an outcome, the sleep diary also was used in the sessions in the BPT program group to individualize the interventions.

We worked individually with each family to promote compliance in wearing the actigraph. This included preventive approaches, such as placing the actigraph over sleeves of night clothes. Children also participated in a compliance session during the home visit, in which they were allowed access to a preferred toy, activity, or other reinforcement for compliance with wearing the actigraph. Parents were asked to conduct brief compliance sessions in the home during the day to facilitate cooperation. We considered an alternative placement of the actigraph for participants who continued to be distressed or noncompliant with wearing the actigraph. Recent practice parameters suggest different placements of the actigraph on the body do not significantly affect the results of actigraph data [50]. Finally for children who continued to remove or attempt to remove the actigraph at bedtime or who became distressed about the placement of the actigraph, we requested that parents try placing the actigraph once the child had fallen asleep, as long as this was within 15 minutes of sleep onset. Of course, this did not provide SL data, but it did provide information about sleep continuity, night awakenings, and early morning awakenings.

2.6. Description of manualized BPT

The BPT sleep program in our study was modeled after the Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network Parent Training program [44,51-53]. The BPT program covered a range of strategies and procedures. Table 1 provides an outline of the BPT sessions. Although not all covered procedures may have been implemented with each child, the program allowed for parents to address current sleep problems and to have knowledge about addressing future sleep issues that could arise. Each session employed direct instruction, modeling, and role-playing to promote parental skill acquisition. For each session, the BPT sleep manual included a therapist script and parent activity sheets for that session. There also were video vignettes, which modeled skills and techniques and showed parents incorrect use of a specific technique to modify a child’s behavior. During discussion parents were encouraged to identify the error in the vignette and to consider alternative responses. Families also were given homework assignments to practice new skills learned in the sessions along with data collection assignments. A cumulative bedtime and sleep intervention plan was developed throughout the 8 weeks of the study and modified as needed based on changes in the child’s sleep. Although the sessions were designed to build on one another, the order was individualized for the family’s needs. There also were optional topics in a few of the sessions to be covered depending on need, level of functioning of the child, and particular sleep disturbances.

Table 1.

Behavioral parent training program session outline.

| Sessions | Topics addressed |

|---|---|

|

A. Basic behavioral

principles |

Introduce overall goals Introduce concepts of antecedent, behavior, and consequence model Introduce the concept of the functions of behavior Introduce how to evaluate and monitor behavior Review completion of sleep diary form |

|

B. Addressing

prevention techniques and bedtime routines |

Discuss preventive techniques Discuss general sleep hygiene recommendations Develop daily schedule and bedtime schedule and routine Develop visual schedules How to develop social stories when appropriate |

|

C. Addressing

reinforcement and extinction procedures for bedtime struggles, night awakenings and early morning awakenings |

Introduce concept of reinforcement and teach contingent implementation of reinforcement Introduce concept of extinction / planned ignoring Introduce use of different extinction techniques to specifically address sleep problems (bedtime struggles, night awakenings, early morning awakenings). Decide upon reinforcement and extinction, and scheduled awakening procedures to implement as appropriate. |

|

D. Addressing

delayed sleep onset and sleep association procedures |

Introduce the concept of stimulus control and its relationship to sleep behaviors Introduce faded bedtime routines and review bedtime routine Introduce teaching new sleep associations Develop specific procedures for teaching new sleep associations |

|

E. Booster and

maintenance session |

Revise and tweak procedures and techniques based on review of sleep diary data and parent-report of progress Discuss strategies for maintenance of behavior change Generate ideas of what to do if changes do not or have not been maintained |

|

OPTIONAL MATERIALS: compliance training |

Introduce parents to the concept of compliance Generate a list of compliance commands Generate a list of noncompliance commands Go over the steps for teaching compliance Identify correct and incorrect use of compliance training via video Role-play correct use of compliance training Go over how to use compliance training to teach a child to “stop.” Problem-solve if things go wrong. Design a compliance training plan for the home. |

|

OPTIONAL

MATERIALS: addressing nighttime fears |

Review why children may have fears around bedtime or nighttime Review their child’s fears with parents Discuss a plan for parents to reassure their child Discuss a plan for the parents to teach their child “brave skills” and other coping strategies For children with severe and specific fears, teach parents how to implement systematic exposure |

2.7. Description of comparison PE program

The content of the sessions for the PE comparison program included a systematic presentation on several topics such as the definition of autism and related conditions, medical considerations for children diagnosed with autism, developmental concerns across the life span, educational and school placement issues, importance and role of advocacy groups, and various treatment and service options. Table 2 outlines the topics covered for each session. This comparison was chosen, as it not only controlled for time and attention but also covered materials providing meaningful information for parents of young children, many of whom had been recently diagnosed. All families who completed the PE program were offered to receive BPT after completing the final measures of week 8.

Table 2.

Pyschoeducational program session outline.

| Sessions | Topics addressed |

|---|---|

| A. Autism diagnosis | Importance of the diagnosis Family’s adjustment Prevalence Etiology Review service delivery models |

|

B. Understanding and

interpreting clinical evaluations |

What do intelligence quotient tests measure and how to understand the scores What are adaptive behavior measures and how to understand the scores Speech, language, and communication measures and their meaning for your child Fine motor measures and their meaning for your child. How to interpret behavior rating measures |

| C. Developmental issues | Current developmental level and expectations Lifespan issues (childhood, adolescence, adulthood) |

|

D. Advocacy and support

services |

National and local support services Parent-to-parent contact Advocacy services and how to use them |

|

E. Treatments and

treatment planning |

Information on evidence-based or best practices Information on other alternative supplementary treatments Review of current services for child Discuss progress and current concerns Discuss other treatment options available for child |

2.8. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were completed using the PASW software package [54] Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic information and feasibility and fidelity data. A modified intent-to-treat principle was used, in which participants who had been enrolled and whose baseline and data from week 4 were available, were included in analyses. Group differences were examined using Fisher exact tests as appropriate for frequency data. Efficacy was examined by conducting 2-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA). ANOVA tests were conducted on CSI scores and the 3 actigraphy variables (TST, SL, and SE). Cohen d effect sizes also were calculated between the groups at the 3 time points. Interrater reliability ratings for treatment fidelity (treatment integrity and parent adherence) were calculated as % agreement by determining the number of items equally rated by both the therapist and the independent observer and divided by the total number of items scored.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Of the 20 participants in each group, data were available for 15 participants randomized to the BPT program and 18 participants to the PE program. In the BPT group, 3 participants were terminated after baseline due to an exclusion making them ineligible (i.e., a medical diagnosis with related sleep disturbances, sedating medication due to onset of an acute illness, inpatient psychiatric hospitalization). In both groups, 2 participants dropped out of the study before week 4 for a dropout rate of 10%. Table 3 displays demographic information.

Table 3.

Demographics.

| BPT (n=15) |

PE (n=18) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (y) | 3.51 (0.98) | 3.6 (1.12) | |

| Gender | 11 boys | 15 boys | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black individuals | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Asian Indian | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | |

| White individuals | 12 (80%) | 12 (66.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Multiethnic | 0 | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Standard cognitive score | 65.73 (17.23) | 68.11 (17.48) | |

| Diagnostic classification | |||

| Autism | 12 (80%) | 17 (94.4%) | |

|

ASD (pervasive

developmental disorder, not otherwise specified) |

3 (20%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

Abbreviations: BPT, behavioral parent training program; PE, psychoeducational program; SD, standard deviation; y, years; ASD, autism spectrum disorders.

Fisher exact tests were conducted to determine any group differences in diagnoses and cognitive level. The groups were not statistically different in the number of children presenting with an autistic disorder vs an ASD diagnosis (pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified) (χ2=1.60; P=.31). The groups also were comparable in the number of children in each group with higher cognitive scores (>70 standard score; n=5 for BPT and n=8 for PE) and lower cognitive scores (≤70 standard score; n=10 for BPT and n=10 for PE) (χ2=.42; P=.72). Standard cognitive scores were obtained using either the Multifactor Emotional Intelligence Scale (MEIS) or the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (SIIS). In the BPT group, 10 children were administered the MEIS and 5 were given the SIIS; and similarly, 11 children were given the MEIS and 7 were given the SIIS in the PE group. Table 4 provides the percentages of the types of sleep disturbances endorsed by the parents at the beginning of the trial for each of the 2 groups.

Table 4.

Types of sleep problems endorsed.

| BPT (% of group) | PE (% of group) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bedtime resistance | 73% | 72% |

| Taking more than one hour to fall asleep | 47% | 50% |

| Falling asleep in places other than own bed | 40% | 50% |

|

Night awakening which disturbs parent or

caregiver |

47% | 67% |

| Early morning awakening | 20% | 22% |

Abbreviations: BPT, behavioral parent training program; PE, psychoeducational program.

3.2. Treatment fidelity (treatment integrity and parent adherence) and interrater reliability

The mean percentage of treatment fidelity for BPT was 98% (range, 83–100) and parent adherence was 93% (range, 75–100). For the PE group, the mean percentage was 99% (range, 50–100) for treatment fidelity and 98% (range, 75–100) for parent adherence. The mean treatment integrity, that is, the delivery of the session goals of the manualized programs, was high for both BPT and PE groups; however, the PE group had a wider range. Likewise, parent adherence generally was high. Mean treatment integrity interrater reliability for the 10% of randomly selected sessions for BPT was 98.2% (range, 81.8–100%) and for PE was 99.1 (90.9%–100%). For parent adherence, mean interrater reliability was 91.8% (range, 66.7%– 100%) for BPT and 98.3% (range, 83.3%–100%) for PE.

3.3. Feasibility and parent satisfaction

The 15 families in BPT attended 73 of the 75 possible sessions (5 sessions×15 participants) or 97.3%. The 18 families in the PE group attended 89 of the 90 possible sessions (5 sessions×18 participants) or 98.9%. Thirteen families completed the parent-satisfaction questionnaire for the BPT group and 17 families completed it for the PE group. Of those parents completing the parent-satisfaction questionnaire, mean parent satisfaction with BPT was 90% (range, 71%–100%), while mean satisfaction with PE was 88.2% (range, 63%–100%). On the items related to the helpfulness of the 5 sessions, 69% of the parents reported the behavior principles as very helpful, while 85% reported this response for the prevention session. Seventy-seven percent reported that the next 2 sessions (sessions C and D) were very helpful, while only 61% found that the last session (booster and maintenance) was very helpful. All other response endorsed the okay rating. No ratings of not helpful were obtained.

3.4. The CSI of the MSPSQ

The ANOVA investigating the CSI revealed a significant group difference between BPT and PE groups (F[1,2]=5.12; P=.03). Main effect for time of study (F[1,2]=1.25, P=.27) and interaction between time of study and group designation (F[1,2]=.08, P=.78) were not significant. Table 5 displays the mean CSI scores and standard deviations for the BPT and PE program groups at each of the 3 data collection time points.

Table 5.

Mean scores for Composite Sleep Index (CSI).

| Baseline Mean (SD) |

Week 4 Mean (SD) |

Week 8 Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BPT (n=15) | 6.53 (2.17) | 4.80 (2.68) | 4.47 (2.90) |

| PE (n=18) | 7.44 (2.60) | 6.83 (2.50) | 6.28 (2.68) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BPT, behavioral parent training program; PE, psychoeducational program.

Effect sizes between the 2 groups also were calculated at each time point and are presented in Fig. 1. Large effect sizes were observed at weeks 4 and 8, with lower CSI scores for the BPT group. At week 8, the CSI score decreased from baseline by 31.5% for the BPT compared to 15.6% for the PE group.

Fig. 1.

Effect sizes between groups for mean Composite Sleep Index scores.

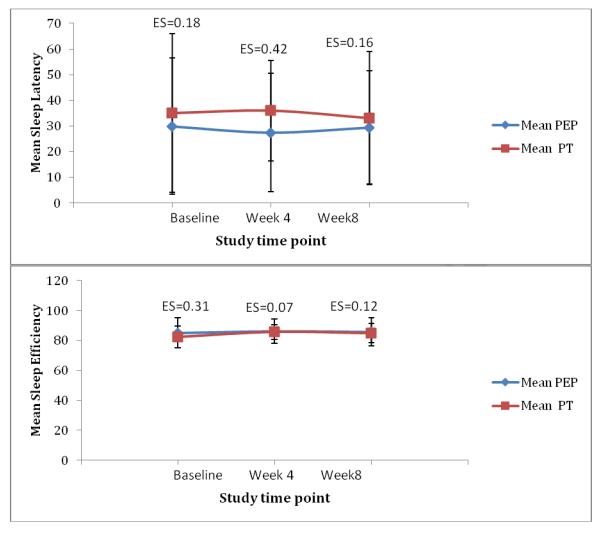

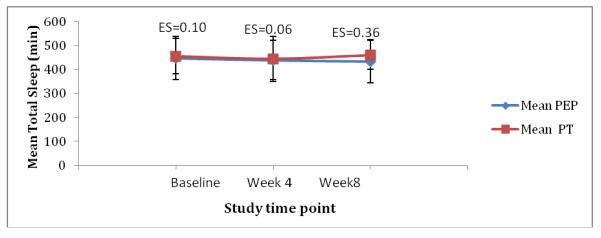

3.5. Actigraphy

Actigraphy data were available on 13 participants in the BPT group and 14 participants in the PE group. Although 5 continuous weekday nights was the data collection protocol, the weekday nights recorded varied from 5 to one night. The mean nights for each group at each assessment point was 4 nights or longer. Missing data were due to failure of the actigraphy devices (n=4), children removing the devices (n=1), or children’s lack of compliance and distress in wearing them (n=8). The mean recordings of TST, SE, and SL across both groups and time points are displayed in Table 6. The ANOVA results for TST were not significant between the BPT and PE groups (F[1,2]=.28, P=.6), nor were there any statistically significant effects across the 2 time points (F[1,2]=.22, P=.64) or interaction between group and time (F[1,2]=.78, P=.39). Similar insignificant results were found for SE (percentage of time spent sleeping while in bed and lights off). The result of the between-group analysis was F(1,2)=.07 (P=.79); the result for SE across time was F(1,2)=.34 (P=.57); and the interaction between time and group also was not significant (F[1,2]=.03, P=.85). Finally, an ANOVA comparing sleep-latency recordings (duration in min between bedtime and falling asleep) across time points revealed no significant difference between the 2 groups (F[1,2]=.55, P=.46.), across time points (F[1,2]=.02, P=.89), or the interaction between time and group (F[1,2]=.69, P=.41).

Table 6.

Mean total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and sleep-latency actigraphy recordings.

| BPT (n=13) |

PE (n=14) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean (SD) |

Week 4 Mean (SD) |

Week 8 Mean (SD) |

Baseline Mean (SD) |

Week 4 Mean (SD) |

Week 8 Mean (SD) |

|

| Total sleep time (min) |

455(73) | 444 (94) | 460 (60) | 448 (90) | 439 (82) | 434(90) |

| Sleep efficiency (%) |

82 (7) | 86 (5) | 85 (6) | 85(10) | 86 (8) | 86 (10) |

| Sleep latency (min) |

35 (31) | 36 (20) | 33 (26) | 29 (27) | 27(23) | 29 (22) |

Abbreviations: BPT, behavioral parent training program; PE, psychoeducational program; SD, standard deviation; min, minutes.

Effect sizes also were calculated for the actigraphy variables and are provided in Fig. 2. For TST, a modest effect size for BPT was observed at week 8. Similarly, a medium effect size supporting the BPT program group was observed for SL at week 4, but this difference was not maintained at week 8.

Fig. 2.

Effect sizes between groups for actigraphy variables

4. Discussion

A 5-session BPT program was developed to target bedtime and sleep problems and was individually delivered to parents of young children with ASD with co-occurring sleep disturbances. The number of sessions and content was determined after reviewing the literature and deciding to provide a breadth of procedures to target an array of bedtime and sleep problems that were either validated earlier in single-subject studies with children with ASD or more broadly in the non-ASD pediatric literature [32-34,37,55,56]. In addition to the 5 core sessions, additional materials were developed to be used as appropriate based on the identified sleep problems, child functioning level, or interfering behaviors such as noncompliance. The purpose of developing this wide range of instruction to parents was to equip all families with behavioral principles and procedures to address a range of sleep disturbances often observed in children with ASD.

After manual development, we piloted the intervention package, BPT, in our small RCT. BPT was compared to a PE program that we developed. The PE program also was a manualized individually delivered program covering topics highly relevant to families of young children with ASD but was not sleep specific. Results supported the feasibility of this manualized 5-session BPT program for young children with ASD and co-occurring sleep disturbances. Similarly, the comparison condition, PE, also was feasible. Ninety-eight percent of the 5 session programs were attended by parents across both groups. Parents who completed the study were satisfied with both the BPT and PE programs according to the parent-completed satisfaction questionnaires.

Treatment fidelity, including both treatment integrity and parent adherence, was high for both groups. Using the manualized programs for both BPT and PE, therapists delivered the session goals as intended. Parents were able to understand the information delivered in the session based on their responses on parent activity sheets and responses from watching the video vignettes. For the BPT group, parents were able to implement the procedures within the home according to results from parent adherence items based on parents’ responses to how they had implemented homework tasks from previous weeks and in review of the cumulative bedtime and sleep plan. High interrater reliability for treatment integrity and parent adherence provided further support for treatment fidelity. The inclusion of treatment fidelity indices and monitoring fidelity in both the active BPT group and the comparison group was unique. Although examining treatment fidelity is held as a critical quality indicator in treatment development research [31,57], it has not been incorporated in other pediatric or ASD sleep intervention research to date in this comprehensive manner.

In our trial, sleep disturbances were broadly defined and included anything from bedtime resistance to night awakening to early morning awakening. The young children with ASD enrolled in our study had an average age of 3 years and presented with a range of sleep disturbances, including resistance and struggles at bedtime, sleep-onset delay, night awakening, sleep association problems, and a few with early morning awakenings. These types of parent-reported sleep problems are similar to those reported by others in a similar age range of children with ASD [12,14] and also are consistent with what have been reported in studies with wider age ranges and older age groups [33,35,58,59]. These collective findings suggest that children with ASD, both younger and older, have similar sleep disturbances. We posit that long-standing sleep problems in children with ASD may easily be avoided if behavioral treatment is implemented in these earlier years.

The BPT program group improved more significantly than the PE group, based on the primary outcome of the CSI scores. Moreover, effect sizes at both week 4 and week 8 for the CSI were robust, though both groups demonstrated decreased CSI scores over the time of the study. The change in the CSI scores from baseline to week 8 was 31.5% for BPT and was 15.6% for PE. This change was less than that found by Wiggs and Stores [33] and Montgomery et al [34] in their parent-training approaches working with a mixed sample of children with various disabilities including ASD. However, the changes in our study are greater than the results from other behaviorally based treatments in ASD-only samples [60]. Hence this manualized parent training approach is worthy of further examination of efficacy within a larger RCT, providing greater statistical power to test for the mediation of salient variables, such as severity of ASD symptoms, level of cognitive functioning, presence of sensory sensitivities, repetitive behaviors, and parent characteristics. It should be noted that the percent changes we observed were less than what was observed with melatonin alone to address SL and night awakening, which have ranged from 33% to more than 60% [60-63]. Melatonin does not address bedtime resistance, which often is a recurring problem for children with ASD, and is not likely to result in a child learning to self-soothe to promote sleep, as in the case of our BPT. Moreover, parents of young children, as those included in our sample (as young as 2 y of age), may be reluctant to have their child try melatonin. Although it is a nonprescription supplement, the long-term risks have not been evaluated.

Several issues are likely to have impacted our small-trial results. Our inclusion criteria were not based on a severity score cutoff on the CSI, which may have been preferable in hindsight. Moreover, children with a range of bedtime and sleep disturbances were enrolled in our study. We may have allowed for the detection of more change in specific sleep problems if we had only focused on a few sleep concerns in the inclusion criteria or a given level of symptom severity rather than a broad variety of sleep problems. Finally, the BPT group CSI score started off lower at baseline than the PE group. Although this difference was not statistically significant (t=.81; P=.42) and it was still in the clinically significant range, this should have been a consideration in our small trial.

In contrast to parent-completed CSI scores, the secondary outcome of actigraphy data did not demonstrate improvement in TST, SE, or SL. A small to medium effect size (.36) for TST was observed at week 8. The disparate findings between parent-report questionnaires and actigraphy have been reported elsewhere [14,15,33,64]. Again there may be several explanations for these discrepancies. The actigraphy data collected were on an even smaller sample, given the challenges of collecting these data, and there were large standard deviations for the actigraphy variables. Although we strived for 5 consecutive weekday nights, this goal was not always obtained. Moreover, actigraphy does not measure bedtime resistance, which often is at the crux of some of the sleep issues of these children. Hence parent reports often are used jointly to assess the bedtime resistance and actigraphy as an objective measure of activity vs sleep. It may be that these children are now more compliant with bedtime and remaining in the bed vs disturbing their parent(s), but not with sleeping. It also is plausible that actual increased sleep state is realized only after a period of more compliance around bedtime and night.

Compared to other interventions, BPT was more intensive than what has been described pertaining to parent-training models to target sleep disturbances in the general pediatric population [65-67]; however, it was similar to a recent RCT with typically developing children [68]. For those studies including some or all children with ASD, our BPT program was similar in intensity to earlier studies [33,37] but more so than others [34, 69]. The Reed et al [35] study provided equivalent or slightly more face-to-face time but was primarily delivered in a group setting instead of an individualized format. Furthermore, our psychosocial RCT provided the design thoroughness not available in most studies in ASD in which there was (1) no control group or a waitlist control group, and thus did not control for attention; (2 ) a less than careful characterization of participants, and (3) a lack of an assessment of treatment fidelity.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

Our initial testing of this manualized parent-training program for sleep disturbances in young children with ASD underwent the rigors of a RCT and was compared to a PE program. However, there were several limitations to our study. Most obviously, our sample size was small. It is interesting that all children, irrespective of group, tended to somewhat improve. We speculate that this finding may have been due to more attention being paid to the child’s sleep and more attention to bedtime, regardless of group. It would perhaps not be surprising that a more structured bedtime routine would be followed if parents were paying more attention to their child’s sleep practices, given that they were recording on their child’s sleep and placing an actigraph on their child. In addition to the small sample size, we had missing data, particularly actigraphy data. Although we made concerted efforts to prepare parents and the child for the use of the actigraph, missing actigraphy data was higher than anticipated.

Additionally, the trial may have been too brief in time. In future studies, a longer treatment period may be needed to see the full behavioral changes of this multicomponent program. It was our clinical anecdotal experience that prompted small changes to be made however, these changes were only towards the final weeks of the study period, and more time was needed to fully observe the response. In a similar way, the sequence of the sessions and the timing of the assessments may not have optimally captured significant treatment effects. For instance, the week-4 midpoint assessment of the study generally occurred after 2 or possibly 3 sessions were provided. The first session provided important information about the behavioral approach on which the other sessions built on, but this session did not require parents to make considerable changes to impact their children’s sleep. Then by the time of the week-8 assessment, families often were implementing a comprehensive plan, and the behavioral changes were still in process. Events such as extinction bursts or considerable restructuring of children’s sleep cycles (e.g., bedtime fading) may have been captured in this assessment time point. It also may have been that these young children’s sleep patterns were more variable and that improved sleep may not have become fully stable in the brief assessment time window. Thus follow-up assessment at later time points would have been greatly advantageous to determine these possibilities and the maintenance of change over time.

Further, given the small sample size our study did not allow us to look at possible predictors. A larger RCT would hopefully be able to examine the unique contributions of likely salient child factors, such as global functioning level; presence of sensory sensitivities; and severity of behaviors such as repetitive, stereotypical, disruptive behaviors. A larger study also would allow for closer examination of parent factors and parent-child interactions known to impact sleep patterns in typically developing young children [70]. Our study did include one home visit in the beginning of the trial but required parents to come into a clinic setting for the 5 sessions. Delivery of the programs in the home may have promoted more success, particularly for this younger age group. This technique also would have allowed for natural opportunities to role-play, provide feedback regarding the use of the behavior procedures taught in the sessions, and to more directly monitor recommended environmental changes.

Hence, in designing a larger RCT we would not only increase the sample size and make the aforementioned changes, we would increase the length of the trial and have outcome measures completed at different time points. For example, instead of 4-week and 8-week time points, 6 and 10 weeks would be a consideration with 1 or 2 booster sessions to review previously taught strategies. The use of booster sessions over a longer time interval has been successful in our other studies [45,51,52]. With a longer trial, the last session on maintenance also may be more relevant and may be judged as more helpful to families. This was the session that parents rated as least helpful. Again our clinical judgment felt that these materials often were premature, given the only-recent changes in the bedtime and sleep behavior when this session was delivered around 8 weeks. Finally, follow-up of these participants for up to 6 to 12 months would be highly worthy to explore the durability of the intervention program over time.

4.2. Highlighted implications

Despite the noted limitations of our study, there are several important implications of this preliminary RCT. First, this was one of few RCTs observing the effectiveness of a parent-training program to target sleep disturbances in a sample of well-characterized young children with ASD. Our study demonstrated the feasibility of the approach and the ability to deliver the treatment in a uniform manner, as demonstrated by the treatment fidelity findings. Parent satisfaction further suggests the acceptability of the intervention. Initial efficacy based on CSI scores in our small RCT favor the BPT program over the comparison group. Although the objective measure of actigraphy did not demonstrate differences between the 2 groups at the end point, many parents in the BPT reported more positively experiencing their child’s bedtime and sleep behaviors based on the CSI scores. Results from our preliminary test of efficacy support the theory that further studies are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources Our study was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH082882-01A2) award to the first author, Autism Speaks, Autism Service, Education, Research and Training grant from the Pennsylvania Bureau of Autism Services, Department of Public Welfare, and National Institute for Research Resources (UL1 RR024153-06 & ULTR000005).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Research Resources, the National Institutes of Health, or any other part of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The National Institute of Mental Health encourages publication of results and free scientific access to data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There were no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Honomichl RD, Goodlin-Jones BL, Burnham M, Gaylor E, Anders TF. Sleep patterns of children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2002;32:553–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1021254914276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Johnson CR. Sleep problems in children with mental retardation and autism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1996;5:673–83. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johnson CR, Turner KS, Foldes EL, Malow BA, Wiggs L. Comparison of sleep questionnaires in the assessment of sleep disturbances in children with autism spectrum disorders. Sleep Med. 2012;13:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wiggs L, Stores G. Sleep patterns and sleep disorders in children with autistic spectrum disorders: insights using parent report and actigraphy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:372–80. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Polimeni MA, Richdale AL, Francis AJ. A survey of sleep problems in autism, Asperger’s disorder and typically developing children. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49:260–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Richdale AL, Prior MR. The sleep/wake rhythm in children with autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;4:175–86. doi: 10.1007/BF01980456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Turner KS, Johnson CR. Behavioral interventions to address sleep disturbances in children with autism spectrum disorders: a review. TECSE. 2012 May 24; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Goldman SE, McGrew S, Johnson K, Richdale A, Clemons T, Malow B. Sleep is associated with problem behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spect Disord. 2011;5:1223–9. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Souders MC, Mason TB, Valladares O, Bucan M, Levy SE, Mandell DS, et al. Sleep behaviors and sleep quality in children with autism spectrum disorders. Sleep. 2009;32:1566–78. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vriend JL, Corkum PV, Moon EC, Smith IM. Behavioral interventions for sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: current findings and future directions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:1017–29. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Richdale AL, Schreck KA. Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, and possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:403–11. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Krakowiak P, Goodlin-Jones B, Hertz-Picciotto I, Croen LA, Hansen RL. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical development: a population-based study. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Allik H, Larsson JO, Smedje H. Insomnia in school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Goodlin-Jones BL, Sitnick SL, Tang K, Liu J, Anders TF. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire in toddlers and preschool children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:82–8. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0b013e318163c39a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hering E, Epstein R, Elroy S, Iancu D, Zelnik N. Sleep patterns in autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29:143–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1023092627223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dahl RE. The impact of inadequate sleep on children’s daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(96)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Graven S. Sleep and Brain Development. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:693–706. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kurth S, Ringli M, Geiger A, LeBourgeois MK, Jenni OG, Huber R. Mapping of cortical activity in the first two decades of life: a high-density sleep electroencephalogram study. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13211–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2532-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bernier A, Carlson SM, Bordeleau S, Carrier J. Relations between physiological and cognitive regulatory systems: infant sleep regulation and subsequent executive functioning. Child Dev. 2010;81:1739–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stickgold R, Walker MP. Sleep and memory: the ongoing debate. Sleep. 2005;28:1225–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Walker MP, Stickgold R. Sleep, memory, and plasticity. annual review of psychology. 2006;57:139–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Goel N, Rao H, Durmer JS, Dinges DF. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin Neurol. 2009;29:320–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sadeh AVI, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, Neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev. 2002;73:405–17. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Beebe DW, Gozal D. Obstructive sleep apnea and the prefrontal cortex: towards a comprehensive model linking nocturnal upper airway obstruction to daytime cognitive and behavioral deficits. J Sleep Res. 2002;11:1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Frank MG, Benington JH. The Role of sleep in memory consolidation and brain plasticity: dream or reality? Neuroscientist. 2006;12:477–88. doi: 10.1177/1073858406293552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Walker MP. Cognitive consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Med. 2008;(9 suppl 1):S29–34. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fallone G, Owens JA, Deane J. Sleepiness in children and adolescents: clinical implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:287–306. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pilcher JJ, Huffcutt AI. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 1996;19:318–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Owens JA, Rosen CL, Mindell JA. Medication use in the treatment of pediatric insomnia: results of a survey of community-based pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111:628. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.e628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mindell JA, Emslie G, Blumer J, Genel M, Glaze D, Ivanenko A, et al. Pharmacologic management of insomnia in children and adolescents: consensus statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1223–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Smith T, Scahill L, Dawson G, Guthrie D, Lord C, Odom S, et al. Designing research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:354–66. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Piazza CC, Fisher WW, Sherer M. Treatment of multiple sleep problems in children with developmental disabilities: faded bedtime with response cost versus bedtime scheduling. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:414–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wiggs L, Stores G. Behavioural treatment for sleep problems in children with severe learning disabilities and challenging daytime behaviour: effect on sleep patterns of mother and child. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:119–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Montgomery P, Stores G, Wiggs L. The relative efficacy of two brief treatments for sleep problems in young learning disabled (mentally retarded) children: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:125–30. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.017202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Reed HE, McGrew SG, Artibee K, Surdkya K, Goldman SE, Frank K, et al. Parent-based sleep education workshops in autism. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:936–45. doi: 10.1177/0883073808331348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Ivanenko A, Johnson K. Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Sleep Med. 2010;11:659–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weiskop S, Richdale A, Matthews J. Behavioural treatment to reduce sleep problems in children with autism or fragile X syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:94–104. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Dis. 1994;24:659–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S. Autism diagnostic observation schedule: A standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Roid GH. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales: Examiner’s Manual. 5th ed Riverside; Itasca, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mullen E. Mullen Scales of Early Learning AGS Edition. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Waltz J, Addis M, Joerner K, Jacobson N. Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: assessment of adherence and competence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:620–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Johnson CR, Handen BL, Butter E, Wagner A, Mulick JA, Sukhodolsky DG, et al. Development of a parent training program for children with pervasive developmental disorders. Behav Interventions. 2007;22:201–21. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology [RUPP] Autism Network Parent training for children with Pervasive Developmental Disorders: A multi-site feasibility trial. Behav Interventions. 2007;22:179–99. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Simonds J, Parraga H. Sleep behaviors and disorders in children and adolescents evaluated at psychiatric clinics. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1984;5:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wiggs L, Stores G. Severe sleep disturbances and daytime challenging behavior in children with severe learning disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1996;40:518–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1996.799799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wiggs L, Stores G. Behavioural treatment for sleep problems in children with severe learning disabilities and challenging daytime behaviour: effect on daytime behaviour. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:627–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Acebo C, LeBourgeois MK. Actigraphy. Respir Care Clin N Am. 2006;12:23–30. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.rcc.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Morgenthaler T, Alessi C, Friedman L, Owens J, Kapur V, Boehlecke B, et al. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep. 2007;30:519–29. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, Handen B, Arnold LE, Johnson C, et al. Medication and parent training in children with pervasive developmental disorders and serious behavior problems: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:1143–54. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bfd669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bearss K, Johnson C, Handen B, Smith T, Scahill L. A pilot study of parent training in young children with autism spectrum disorders and disruptive behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:829–40. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bearss K, Lecavalier L, Minshawi N, Johnson C, Smith T, Handen B, et al. Toward an exportable parent training program for disruptive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3:169–80. doi: 10.2217/npy.13.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].SPSS Inc. Predictive Analytic SoftWare (PASW) SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29:1263–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Weiskop S, Matthews J, Richdale A. Treatment of sleep problems in a 5-year-old boy with autism using behavioural principles. Autism. 2001;5:209–21. doi: 10.1177/1362361301005002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lord C, Wagner A, Rogers S, Szatmari P, Aman MG, Charman T, et al. Challenges in evaluating psychosocial interventions for autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disabil. 2005;35:695–708. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Malow BA, Marzec ML, McGrew SG, Wang L, Henderson LM, Stone WL. Characterizing sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders: a multidimensional approach. Sleep. 2006;29:1563–71. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schreck K, Mulick J. Parental report of sleep problems in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:127–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1005407622050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Sebastiani T, Panunzi S, Valente D. Controlled-release melatonin, singly and combined with cognitive behavioural therapy, for persistent insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2012;21:700–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Cerquiglini A, Bernabei P. An open-label study of controlled-release melatonin in treatment of sleep disorders in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:741–52. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Malow B, Adkins K, McGrew S, Wang L, Goldman S, Fawkes D, et al. Melatonin for sleep in children with autism: a controlled trial examining dose, tolerability, and outcomes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1729–37. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1418-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wright B, Sims D, Smart S, Alwazeer A, Alderson-Day B, Allgar V, et al. Melatonin versus placebo in children with autism spectrum conditions and severe sleep problems not amenable to behaviour management strategies: a randomised controlled crossover trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:175–84. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Moon E, Corkum P, Smith I. Case study: a case-series evaluation of a behavioral sleep intervention for three children with autism and primary insomnia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;36:47–54. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Adams LA, Rickert VI. Reducing bedtime tantrums: comparison between positive routines and graduated extinction. Pediatrics. 1989;84:756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hiscock H, Wake M. Randomised controlled trial of behavioural infant sleep intervention to improve infant sleep and maternal mood. BMJ. 2002;324:1062–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7345.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Seymour FW, Brock P, During M, Poole G. Reducing sleep disruptions in young children: evaluation of therapist-guided and written information approaches: a brief report. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1989;30:913–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Schlarb A, Velten-Schurian K, Poets C, Hautzinger M. First effects of a multicomponent treatment for sleep disorders in children. Nature Sci Sleep. 2011;3:1–11. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S15254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Durand VM. Treating sleep terrors in children with autism. J Pos Behav Interventions. 2002;4:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Teti DM, Kim B, Mayer G, Countermine M. Maternal emotional availability at bedtime predicts infant sleep quality. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24:307–15. doi: 10.1037/a0019306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.