Abstract

Purpose

The purposes of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with response rate, resectability, and survival after cisplatin/interferon α-2b/doxorubicin/5-flurouracil (PIAF) combination therapy in patients with initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Patients and Methods

The study included two groups of patients treated with conventional high-dose PIAF (n=84) between 1994 and 2003 and those without hepatitis or cirrhosis treated with modified PIAF (n=33) between 2003 and 2012. Tolerance of chemotherapy, best radiographic response, rate of conversion to curative surgery, and overall survival were analyzed and compared between the two groups, and multivariate and logistic regression analyses were applied to identify predictors of response and survival.

Results

The modified PIAF group had a higher median number of PIAF cycles (4 vs. 2, P = .049), higher objective response rate (36% vs. 15%, P = .013), higher rate of conversion to curative surgery (33% vs. 10%, P = .004), and longer median overall survival (21.3 vs. 10.6 months, P = .002). Multivariate analyses confirmed that positive hepatitis B serology (hazard ratio [HR], 1.68; 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.59) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≥2 (HR, 1.75; 95% CI 1.04 to 2.93) were associated with worse survival while curative surgical resection after PIAF treatment (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.35) was associated with improved survival.

Conclusions

In patients with initially unresectable HCC, the modified PIAF regimen in patients with no hepatitis or cirrhosis is associated with improved response, resectability, and survival.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is potentially curable by surgical resection,[1, 2] local ablation,[3, 4] or liver transplantation[5, 6]. However, most patients with HCC present with unresectable disease accompanied by background liver disease which has an independent effect on patients’ survival. Therefore, effective neoadjuvant therapeutic options are limited for these patients.

Conventionally, HCC has been considered a chemotherapy-resistant tumor, and numerous clinical trials of a wide variety of chemotherapeutic and hormonal agents have failed to show satisfactory results.[7] However, multiple experts panels concluded that the underlying liver disease is a major confounding factor that independently affects HCC treatment outcome. This fact is very pertinent to failed chemotherapy trials in HCC. This is because the majority of patients did not tolerate full doses and regular schedules of chemotherapy, and therefore, the poor outcome and short survival were related, in part, to deterioration of the underlying liver disease. Notably, the PIAF regimen, consisting of cisplatin, interferon α-2b, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), produced a relatively high objective response rate in the initial phase II study of this regimen for patients with unresectable HCC.[8] Although a phase III clinical trial comparing PIAF with doxorubicin did not show an overall survival benefit of PIAF,[9] the objective response rate of the regimen was confirmed. However, the potential neoadjuvant role of of PIAF in unresectable HCC remained an open question because the populations in previous studies had high prevalences (>80%) of cirrhosis and hepatitis B,[8-11] both of which have been reported to negatively affect the course of intensive chemotherapy and ultimately patients’ surgical candidacy.[10, 12] Since 1994, our group has prospectively followed up all the patients who have received PIAF treatment at our institution for initially unresectable HCC. From January 1994 through May 2003, PIAF was administered in the context of an expanded institutional phase II trial. In June 2003, on the basis of the initial results of our phase II trial and that of another group[8], the patient selection criteria for PIAF and the PIAF treatment protocol were modified.

The objectives of the current study were to compare the response rate, resectability, and survival between the patients treated with the original PIAF regimen and the optimally selected patients treated with the modified PIAF regimen and to explore the factors associated with survival, response to the PIAF regimen, and improved resection rate.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study population consisted of two groups of patients, the conventional PIAF group (n=84) and the modified PIAF group (n=33) (Table 1). The conventional PIAF group was a prospective cohort in an extended single-arm institutional phase II trial assessing the efficacy of the PIAF regimen and conducted between January 1994 and June 2003. The modified PIAF group was a prospective registry cohort treated with the modified PIAF regimen between July 2003 and June 2012. We performed a retrospective analysis of both cohorts.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics*

| Characteristic | Conventional PIAF (n=84) |

ModifiedPIAF (n=33) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58 (22-80) | 49 (11-71) | <.01 |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 61 (73) | 15 (45) | .006 |

| ECOG PS, no. (%) | |||

| 0 | 42 (50) | 22 (67) | .388 |

| 1 | 23 (27) | 9 (27) | |

| 2 | 14 (17) | 2 (6) | |

| 3 | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Positive hepatitis B serology, no. (%) | 36 (43) | 6 (18) | .018 |

| Positive HBsAg, no. (%) | 12 (14) | 2 (6)** | |

| Positive HBcAb, no. (%) | 35 (42) | 6 (18)** | |

| Positive hepatitis C serology, no. (%) | 14 (17) | 2 (6) | .230 |

| Cirrhosis, no. (%) | 41 (49) | 2 (6)*** | <.001 |

| Child-Pugh class, no. (%) | |||

| A | 76 (90) | 31 (94) | .723 |

| B | 8 (10) | 2 (6) | |

| ALT level, IU/L | 68 (21-532) | 45 (16-147) | <.001 |

| AFP level, ng/mL | 203.2 (1.7-975,959.4) | 8201.8 (1.7-1,869,950) | .012 |

| Maximum tumor size, mm | 100 (25-220) | 116 (21-200) | .822 |

| Number of tumors, no. (%) | |||

| One | 45 (54) | 7 (21) | .002 |

| Multiple | 39 (46) | 26 (79) | |

| Lymph node metastases, no. (%) | 23 (27) | 15 (45) | .079 |

| Extrahepatic disease, no. (%) | 21 (25) | 11 (33) | .367 |

| Major vascular involvement, no. (%) | 20 (24) | 9 (27) | .812 |

Abbreviation: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb, hepatitis B core antibody.

Values in table are median (range) unless otherwise indicated.

Four patients had no active hepatitis with serologic evidence of past infection (HBsAg− HBcAb+), and 2 patients had active infection (HBsAg+, HBcAb+) but it was well controlled with antiviral therapy.

Postoperative histologic diagnosis in surgical specimens.

Diagnosis and assessment of resectability

HCC was diagnosed by histologic examination of tumor tissue. Treatment options for every patient were discussed during a multidisciplinary Liver Tumor Study Group, and resectability was assessed by experienced hepatobiliary surgeons on the basis of imaging findings (e.g., tumor size, tumor location, tumor distribution, invasion, and presence of extrahepatic disease), function of the underlying liver, presence of medical comorbidities, and patient performance status.

Indications for PIAF treatment

General indications for PIAF treatment were as follows: unresectable advanced HCC, life expectancy more than 12 weeks, platelet count 100,000/mm3 or greater, absolute granulocyte count 1500/mm3 or greater, serum bilirubin level 2 mg/dL or less, serum albumin level 3 g/dL or greater, serum creatinine level 1.5 mg/dL or less, normal cardiac function, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score 2 or less. Since June 2003, on the basis of results of the phase II trial, we adopted the following as relative contraindications to PIAF treatment at our institution: positive hepatitis B serology (i.e., presence of hepatitis B surface antigen or anti-hepatitis B core antibody) with no ongoing antiviral therapy, positive hepatitis C serology (i.e., presence of anti-hepatitis C antibody), histologic or clinical evidence of established cirrhosis, and ECOG performance status 2 or greater.

Treatment protocols

The conventional PIAF regimen consisted of cisplatin 80 mg/m2 on day 1, interferon α-2b 5 MU/m2 on days 1 through 4, doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 on day 1, and 5-FU 500 mg/m2 over 24 h on days 1 through 4. The modified PIAF regimen consisted of cisplatin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 through 4, interferon α-2b 4 MU/m2 on days 1 through 4, doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 on day 1, and 5-FU 400 mg/m2 as a bolus infusion on days 1 through 4. Each treatment was repeated every 4 weeks for up to 6 cycles. Several patients with good response and tolerance received up to two more cycles of PIAF after completion of the six cycles of PIAF that were part of the planned protocol treatment. In patients who developed grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events, treatment was withheld until the event resolved to grade 1 or less, and doses were reduced by 25% in the next cycle. Patients who completed scheduled PIAF treatment but still had unresectable tumors received additional therapies including TACE and/or other systemic therapy considering their oncologic status and physical conditions.

Follow-up and evaluation of response

Liver functions, electrolytes, and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level were examined every 4 weeks during PIAF treatment. A baseline computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained before day 1 of the first PIAF cycle, and the disease status was assessed by enhanced CT every 8 weeks (= 2 cycles) during PIAF treatment. Response to chemotherapy determined by an investigator was confirmed by radiologists and described according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.[13] Objective response rate was defined as the percentage of patients who had a complete response or partial response during PIAF treatment. Toxic effects were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, and time to severe adverse event (grade 3 or higher) was retrospectively reviewed for every patient.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Overall survival was measured from day 1 of the first PIAF cycle to the date of death or last follow-up. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between curves were evaluated using the log-rank test.

To identify prognostic factors for survival, a multivariate regression analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model with backward elimination for variables with P < .1 in univariate analysis. To identify factors associated with an objective response to chemotherapy, a multivariate analysis was performed using the logistic regression model for clinical variables with P < .1 in univariate analysis. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS software (version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Compared to the conventional PIAF group, the modified PIAF group had a younger median age and a higher proportion of females. Positive hepatitis serology and liver cirrhosis were significantly less common in the modified PIAF group, and there was a trend toward better performance status in the modified PIAF group, reflecting the modified patient selection criteria and only limited patients with well controlled hepatitis, good liver function, and acceptable physical condition underwent the modified PIAF treatment when the relative contraindication factors were present. There were no differences between the conventional PIAF group and the modified PIAF group in maximum tumor size, nodal involvement, presence of extrahepatic disease, or presence of major vascular invasion. However, number of tumors and serum AFP levels were higher in the modified PIAF group.

Adverse events, objective response rate, and rate of conversion to resectability

Outcomes of PIAF treatment are summarized in Table 2 in comparison with reported outcomes in previous studies. The median number of PIAF cycles was significantly higher in the modified PIAF group (4 vs. 2; P = .049). Although the cumulative incidence of grade 3 or higher adverse events during PIAF treatment was similar in the two groups (58% for conventional PIAF vs. 61% for modified PIAF), median number of cycles of PIAF before occurrence of a grade 3 or higher adverse event was significantly longer in the modified PIAF group (2 cycles vs. 1 cycle; P = .003). As a result, the modified PIAF regimen was associated with a higher objective response rate (36% vs. 15%; P = .013) and rate of conversion to curative surgery (33% vs. 10%; P = .004).

Table 2.

Treatment Details and Outcomes in Patients Treated with PIAF in the Current Study and Previous Studies

| Treatment Details and Outcomes |

Conventional PIAF (n=84) |

Modified PIAF (n=33) |

P | Phase II (Leung, 1999) (n=50) |

Phase III (Yeo, 2005) (n=94) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIAF protocol | |||||

| Cisplatin | 80 mg/m2, day 1 | 20 mg/m2, days 1-4 | 20 mg/m2, days 1-4 | 20 mg/m2, days 1-4 | |

| Interferon α-2b | 5 MU/m2, days 1-4 | 4 MU/m2, days 1-4 | 5 MU/m2, days 1-4 | 5 MU/m2, days 1-4 | |

| Doxorubicin | 40 mg/m2, day 1 | 40 mg/m2, day 1 | 40 mg/m2, day 1 | 40 mg/m2, day 1 | |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 500 mg/m2, days 1-4 | 400 mg/m2, days 1-4 | 400 mg/m2, days 1-4 | 400 mg/m2, days 1-4 | |

| No. of cycles, median (range) | 2 (1-8) | 4 (1-8) | .049 | 3 (1-6) | 3 |

| ≥Grade 3 adverse event during PIAF treatment, no. (%) |

49 (58) | 20 (61) | .822 | NA | 77 (82) |

| Cycles of PIAF before any ≥grade 3 adverse event, median (range) |

1 (1-3) | 2 (1-6) | .003 | NA | NA |

| Pretreatment tumor size, mm, median (range) |

100 (25-220) | 116 (21-200) | .822 | 100 (5-220) | NA |

| Best response,* no. (%) | |||||

| Partial response | 13 (15) | 12 (36) | .172 | 13 (26) | 19 (21) |

| Stable disease | 45 (54) | 14 (42) | 14 (28) | 35 (38) | |

| Progressive disease | 15 (18) | 3 (9) | 15 (30) | 37 (41) | |

| Unknown | 11 (13) | 4 (12) | 8 (16) | 0 (0) | |

| Objective response, no. (%) | 13 (15) | 12 (36) | .013 | 13 (26) | 19 (21) |

| Conversion to curative surgery, no.(% (%) |

8 (10) | 11 (33) | .004 | 9 (18) | 7 (8) |

Response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. NA: not available

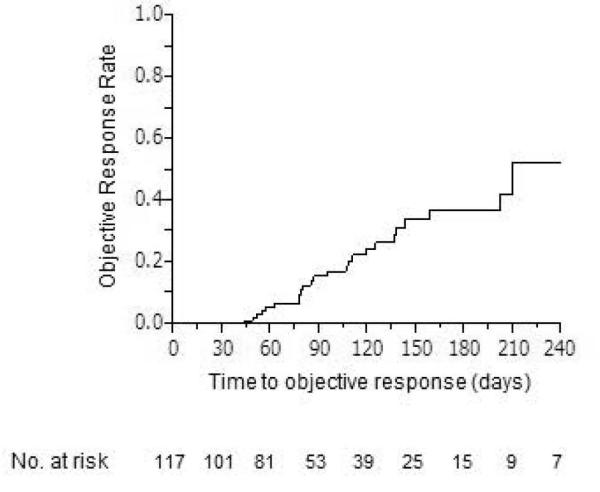

Figure 1 shows cumulative objective response rate during PIAF treatment. Median time to response was 210 days and the cumulative response rates were estimated as 4.2% at 8 weeks (2 cycles of PIAF), 15.4% at 12 weeks (3 cycles of PIAF), 22.3% at 16 weeks (4 cycles of PIAF), 31.2% at 20 weeks (5 cycles of PIAF), and 36.9% at 24 weeks (6 cycles of PIAF), respectively.

Figure 1.

Cumulative objective response rate over PIAF treatment period.

When the cut-off value for number of PIAF cycles was adjusted from one through more than six, five or more PIAF cycles was associated with the highest odds ratio (OR) for objective response to chemotherapy (OR, 13.1; 95% CI, 4.67 to 36.7; P < .01). Multivariate analysis confirmed that five or more PIAF cycles was the only predictor of objective response to PIAF treatment (OR, 15.6; 95% CI, 4.9 to 49.5; P < .001) (Table 3). The patients with conversion to curative surgery had a significantly higher median number of PIAF cycles (5 vs. 2; P = .003) and better response compared to the patients whose disease remained unresectable, though the median pretreatment tumor size was similar (108 mm vs. 100 mm in median, P = 0.78).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Objective Response

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age >65 years | .831 | |||

| Male gender | .016 | 0.33 (0.13-0.81) | .130 | |

| ECOG PS ≥2 | .387 | |||

| Positive hepatitis B serology | .068 | 0.37 (0.13-1.08) | .477 | |

| Positive hepatitis C serology | .360 | |||

| Cirrhosis | .057 | 0.35 (0.12-1.03) | .823 | |

| Child-Pugh class B | .913 | |||

| ALT level >40 IU/L | .290 | |||

| AFP level >100 ng/mL | .216 | |||

| Tumor size >100 mm | .440 | |||

| Multiple tumors | .193 | |||

| Nodal involvement | .935 | |||

| Extrahepatic disease | .140 | |||

| Major vascular involvement | .553 | |||

| Modified PIAF regimen | .016 | 3.12 (1.24-7.86) | .140 | |

| No. of PIAF cycles ≥5 | <.001 | 13.1 (4.67-36.7) | <.001 | 15.6 (4.9-49.5) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

Treatment after PIAF

Among the 98 unresectable patients after PIAF treatment, 27 (36%) patients in the conventional PIAF group and 11 (50%) patients in the modified PIAF group received additional therapies. However, because of the high rate of severe adverse event and decreased performance status associated with PIAF treatment, available therapy was limited after completion of or failure from the treatment. Eventually, additional systemic therapy was performed in 23 (30%) patients in the conventional PIAF group and 7 (32%) patients in the modified PIAF group, respectively (P = .65). 5-fluorouracil or capecitabine based regimen was the most common regimens in either of the groups (87% vs. 86%, P = 1). Sorafenib was used in only one patient after the modified PIAF treatment. TACE was selected in 5 (7%) patients in the conventional PIAF group and 4 (18%) patients in the modified PIAF group, respectively (P = .26). Radioembolization using yttrium 90 was performed for only one patient in the modified PIAF group.

Survival

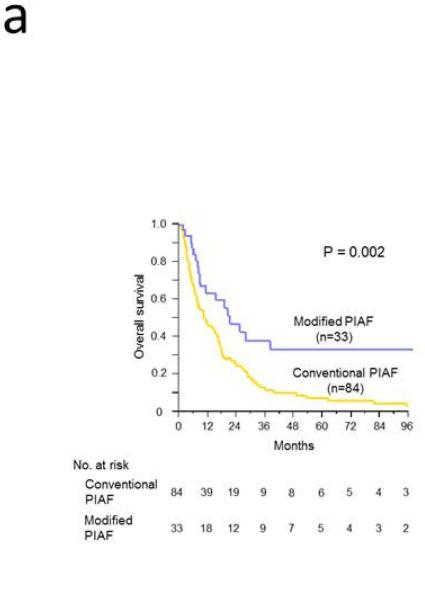

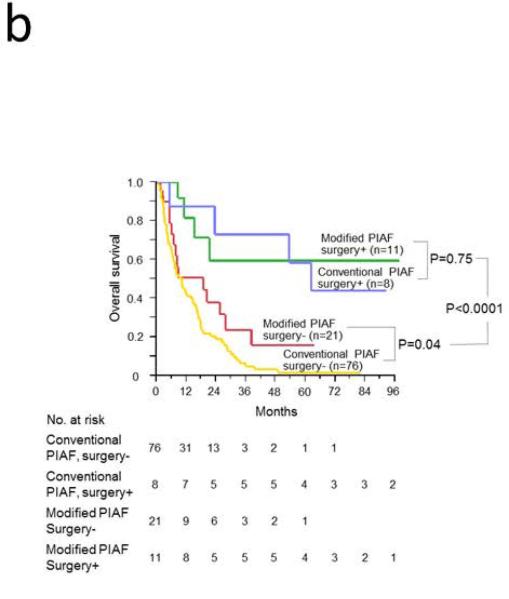

At the time of this analysis, of the 84 patients in the conventional PIAF group, 78 had died, 5 had been lost to follow-up, and 1 was still alive with a median follow-up period of 10.3 months (range, 1 to 211 months). Of the 33 patients in the modified PIAF group, 15 had died, 6 had been lost to follow-up, and 12 were still alive with a median follow-up period of 15.3 months (range, 2 to 98 months). Intent-to-treat survival analysis revealed that median overall survival was significantly longer in the modified PIAF group (21.3 months vs. 10.6 months; P = .002); the 3-year overall survival rate was 33.5% in the modified PIAF group vs. 10.1% in the conventional PIAF group (Figure 2A). When the groups were stratified according to whether patients underwent curative surgery or not, patients who underwent curative surgery had better survival regardless of which PIAF protocol was used (P < .0001) (Figure 2B). Notably, among the patients who did not undergo curative surgery, patients treated with the modified PIAF regimen had better survival than those treated with the conventional PIAF regimen (19.0 months vs. 10.1 months; P = .04).

Figure 2.

Overall survival in patients with initially unresectable HCC treated with the PIAF regimen. A. Intent-to-treat analysis for conventional and modified PIAF groups. B. Survival differences by PIAF regimen in patients with and without surgery.

Multivariate analysis confirmed that ECOG performance status ≥2 (hazard ratio [HR], 1.75; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.93; P = .034) and positive hepatitis B serology (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.59; P = .020) were associated with worse overall survival while 5 or more cycles of PIAF therapy (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.93; P = .024), curative surgical resection (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.35; P < .001), and additional chemotherapy or transarterial chemoembolization after completion or failure of PIAF regimen (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.61; P < .001) were associated with better overall survival (Table 3).

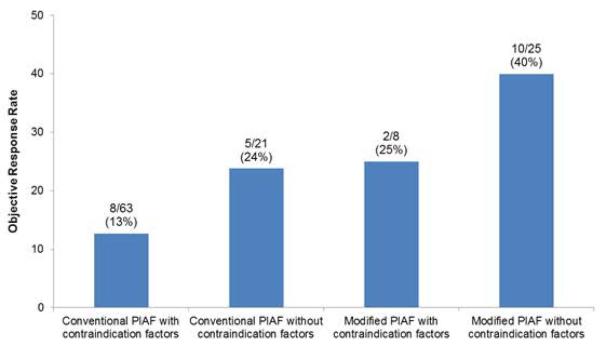

The median increase in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level after initiation of PIAF treatment was significantly higher in patients with positive than in patients with negative hepatitis B serology (30 IU/L vs. 1 IU/L; P = .008), and patients with positive hepatitis B serology had a higher incidence of hepatic dysfunction (ALT >100 IU/L) during PIAF treatment (16/33, 48% vs. 11/69; 16%, P = .0006) according to the data for the 102 patients in whom both pre- and post-PIAF serum ALT levels were available. Furthermore, patients with ECOG performance status score 2 or greater had a higher incidence of termination of PIAF treatment because of poor tolerance than did patients with ECOG performance score of 0 or 1 (6/21, 29% vs. 15/81, 16%; P = .23). When comparing objective response rate based on the PIAF protocols and presence of the relative contraindication factors (i.e., positive hepatitis B serology, positive hepatitis C serology, ECOG performance status of 2 or greater, or liver cirrhosis), modified PIAF for patients without contraindication factors had highest objective response rate (40%), while conventional PIAF for patients with the contraindication factors showed lowest objective response rate (13%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Objective response rate based on PIAF protocols and presence of contraindication factors. *The contraindication factors include: positive hepatitis B serology, positive hepatitis C serology, ECOG performance status of 2 or greater, and clinically or histologically proven established liver cirrhosis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, in patients with initially unresectable large HCC, the modified PIAF regimen in patients with no cirrhosis or hepatitis B was associated with improved tolerance, rate of response, resectability, and survival. Receipt of five or more cycles of PIAF was associated with higher objective response rate and a rate of conversion to curative surgery of 33%. PIAF treatment was independently associated with improved survival in multivariate analysis regardless of whether surgical resection was performed. Taken together, these observations argue against the notion that HCC is uniformly chemoresistant and lend support for therapeutic approaches that take into account both HCC and any underlying liver disease.[14] Our approach, if validated, could lead to establishing a successful neoadjuvant approach in potentially resectable large HCC tumors.

The emergence of chemotherapy in the 1950s has led to the availability of neoadjuvant systemic therapies for patients with advanced solid tumors. However, systemic cytotoxic therapies have demonstrated a very limited impact on the resectability of advanced HCC despite several studies showing reasonable response rates.[15-18] This is mainly because advanced underlying liver disease is associated with poor survival and tolerance of chemotherapy and is a contraindication to surgery in the first place. Recently, molecular characterization of hepatocarcinogenesis has led to recognition of defined aberrant signaling pathways, which has facilitated subsequent development of targeted agents as potential treatments for HCC, either alone or in combination with other therapies. In 2007, sorafenib was approved for treatment of patients with unresectable HCC based on improving overall survival. However, sorafenib showed a very low response rate in randomized phase III trials[19, 20] and failed to downsize tumors to a resectable stage.

In a previous study, Leung et al.[8] reported that treatment with the PIAF regimen permitted curative surgery in 18% of patients with initially unresectable HCC (Table 2). Although a subsequent phase III study by Yeo et al. showed a surgical conversion rate of only 8% (Table 2),[9]the study confirmed overall objective rate of 21% and also excellent long-term survival was also confirmed in patients undergoing curative surgery after PIAF chemotherapy.[21] In the current study, the patients treated with conventional PIAF had an objective response rate of 15% and a rate of conversion to curative surgery of 10%. However, selected patients with no cirrhosis treated with modified PIAF similr to phase II and III had substantially higher rates of objective response (36%), and conversion to curative surgery (33%), and also had prolonged survival, even in patients with ultimately unresectable disease. Furthermore, the median size of tumor in patients achieving curative surgery was 10.8 cm and this was substantially larger than the reported median size of HCC (4.7 – 7.0 cm) in randomized trials of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE).[22, 23] These results suggest that neoadjuvant PIAF systemic therapy can offer a chance of cure even in selected patients with large HCC who are not good candidates for TACE.

Another noteworthy result of this study is that five or more cycles of PIAF appeared to be required for meaningful objective response and optimal survival regardless of the PIAF protocol. This result suggests that the PIAF regimen must be tolerable in order to produce improved outcomes. The multivariate analysis showed that patients with chronic liver disease and worse performance status had worse prognosis. Indeed, these patients had a higher incidence of hepatotoxicity or termination of PIAF treatment because of toxic effect. With a carefully selected patient population and dose modification, tolerance of PIAF treatment was clearly improved, which resulted in higher number of cycles of treatment than in our conventional-PIAF cohort or previous studies. These findings indicate that PIAF treatment should be limited to patients with no chronic liver disease and good performance status.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and the difficulty of simple comparisons between the two cohorts because they differed with respect to both the PIAF protocol and the patient selection. However, the modified PIAF dosing was based on results from other PIAF studies and the higher adverse events rate with the conventional PIAF at our center. Furthermore, the current results are based on prospectively collected data, and the modified PIAF group showed substantially better outcomes compared to the conventional PIAF groups (Figure 3) and previous PIAF studies that used very similar chemotherapy protocols with the modified PIAF group (Table 2).[8, 9] In addition, in the current era of effective anti-hepatitis B treatment, negative influence of hepatitis B on PIAF treatment could be minimized with adequate anti-viral therapy. Therefore, further investigation about the effectiveness of PIAF therapy for patients with anti-hepatitis B treatment is needed. Another limitation is the potential small percentage of patients with no cirrhosis who would be good candidates for PIAF regimen. However, our group and others observed a notable decreasing trends of the incidence of cirrhosis (55-60%) and hepatitis (30-47%) in HCC in recent years. 19,[24, 25], than those of historic patients whose data were used to establish the HCC staging systems[26-30] (hepatitis = 82.3%-100%, and cirrhosis = 77-100%). This is consistent with and complementary to multiple recent reports indicating the rising incidence of HCC cases that are not associated with hepatitis or cirrhosis, specifically among NASH and metabolic syndrome CLDs which can progress to HCC without apparent cirrhosis[31-39].

In conclusion, in the current era of early goal-directed therapy and a focus on cost-effectiveness, it has become ever more important that we discriminate between HCC patients at risk for clinically relevant adverse outcomes and mortality following specific therapy, such as treatment with the PIAF regimen, and patients at low risk for adverse outcomes, who stand to benefit most from therapy. Our proposed personalized therapy approach of neoadjuvant PIAF regimen to patients with no advanced chronic liver disease preserves the surgical (curative) option to patients who have a disease considered unresectable at diagnosis.

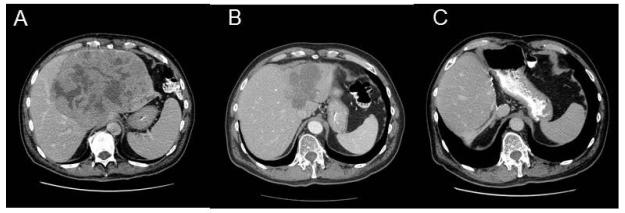

Figure 4.

Size reduction of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after PIAF therapy. A 61-year-old man with huge hepatocellular carcinoma received six cycles of modified PIAF therapy and eventually was able to undergo curative resection after impressive size reduction of the tumor. At this writing, the patient is alive with no evidence of disease 74 months after surgery. A. Before PIAF therapy, B. After six cycles of PIAF therapy. C. After extended left hepatectomy.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Survival

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age >65 years | .140 | |||

| Male gender | .086 | 1.45 (0.95-2.25) | .493 | |

| ECOG PS ≥2 | .088 | 1.54 (0.94-2.54) | .034 | 1.75 (1.04-2.93) |

| Positive hepatitis B serology | .007 | 1.81 (1.19-2.75) | .020 | 1.68 (1.08-2.59) |

| Positive hepatitis C serology | .685 | |||

| Cirrhosis | .016 | 1.67 (1.10-2.51) | .910 | |

| Child-Pugh class B | .025 | 2.45 (1.13-4.71) | .267 | |

| ALT level >40 IU/L | .142 | |||

| AFP level >100 ng/mL | .347 | |||

| Tumor size >10 cm | .456 | |||

| Multiple tumors | .693 | |||

| Nodal involvement | .783 | |||

| Extrahepatic disease | .919 | |||

| Major vascular involvement | .495 | |||

| Modified PIAF regimen | .002 | 0.46 (0.27-0.76) | .478 | |

| No. of PIAF cycles ≥5 | <.001 | 0.42 (0.25-0.67) | .024 | 0.56 (0.33-0.93) |

| Curative surgery | <.001 | 0.18 (0.08-0.36) | <.001 | 0.15 (0.07-0.35) |

| Additional treatment* | .002 | 0.51 (0.33-0.78) | <.001 | 0.39 (0.25-0.61) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

Additional transarterial chemoembolization or chemotherapy after completion or failure of PIAF regimen.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grants CA170035-01 (to A.O.K.), and CA106458-01 (to M.M.H.), and Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672, and by a grant from Schering-Plough Inc. to YZP

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: All authors indicate no financial disclosures, conflicts of interest,and/or acknowledgements

REFERENCES

- 1.Arii S, Yamaoka Y, Futagawa S, et al. Results of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for small-sized hepatocellular carcinomas: a retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Hepatology. 2000;32:1224–1229. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Hirohashi S, et al. Early hepatocellular carcinoma as an entity with a high rate of surgical cure. Hepatology. 1998;28:1241–1246. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, et al. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology. 2008;47:82–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.21933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiina S, Tateishi R, Arano T, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.425. quiz 578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, Gores GJ, Langer B, Perrier A. Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an international consensus conference report. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e11–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todo S, Furukawa H. Living donor liver transplantation for adult patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: experience in Japan. Ann Surg. 2004;240:451–459. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137129.98894.42. discussion 459-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonetti RG, Liberati A, Angiolini C, Pagliaro L. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:117–136. doi: 10.1023/a:1008285123736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung TW, Patt YZ, Lau WY, et al. Complete pathological remission is possible with systemic combination chemotherapy for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1676–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo W, Mok TS, Zee B, et al. A randomized phase III study of doxorubicin versus cisplatin/interferon alpha-2b/doxorubicin/fluorouracil (PIAF) combination chemotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1532–1538. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung TW, Tang AM, Zee B, et al. Factors predicting response and survival in 149 patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated by combination cisplatin, interferon-alpha, doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Cancer. 2002;94:421–427. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin XY, Lu MD, Liang LJ, Lai JM, Li DM, Kuang M. Systemic chemo-immunotherapy for advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2526–2529. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i16.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo W, Lam KC, Zee B, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing systemic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1661–1666. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vauthey JN, Lauwers GY, Esnaola NF, et al. Simplified staging for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1527–1536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobbio-Pallavicini E, Porta C, Moroni M, et al. Epirubicin and etoposide combination chemotherapy to treat hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a phase II study. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1784–1788. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai KH, Tsai YT, Lee SD, et al. Phase II study of mitoxantrone in unresectable primary hepatocellular carcinoma following hepatitis B infection. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;23:54–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00258459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanioka H, Tsuji A, Morita S, et al. Combination chemotherapy with continuous 5-fluorouracil and low-dose cisplatin infusion for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:1891–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaniboni A, Simoncini E, Marpicati P, Marini G. Phase II study of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and high dose folinic acid (HDFA) in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1988;57:319. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau WY, Leung TW, Lai BS, et al. Preoperative systemic chemoimmunotherapy and sequential resection for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;233:236–241. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200102000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaseb AO, Morris JS, Hassan MM, et al. Clinical and prognostic implications of plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3892–3899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huitzil-Melendez FD, Capanu M, O’Reilly EM, et al. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: which staging systems best predict prognosis? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2889–2895. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, et al. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:918–928. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<918::aid-cncr2820560437>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung TW, Tang AM, Zee B, et al. Construction of the Chinese University Prognostic Index for hepatocellular carcinoma and comparison with the TNM staging system, the Okuda staging system, and the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program staging system: a study based on 926 patients. Cancer. 2002;94:1760–1769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson JM, Sherman M, Tavill A, Abecassis M, Chejfec G, Gramlich T. AHPBA/AJCC consensus conference on staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: consensus statement. HPB (Oxford) 2003;5:243–250. doi: 10.1080/13651820310015833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S27–34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ertle J, Dechene A, Sowa JP, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of apparent cirrhosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2436–2443. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman G, Brunt EM, Petrovic LM, Chejfec G, Layden TJ, Cotler SJ. Does nonalcoholic fatty liver disease predispose patients to hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1761–1766. doi: 10.5858/132.11.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto E, Tokushige K. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Growing evidence of an epidemic? Hepatol Res. 2012;42:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaoki Y, Hyogo H, Aikata H, et al. Recent trend of clinical features in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:368–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paradis V, Zalinski S, Chelbi E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with metabolic syndrome often develop without significant liver fibrosis: a pathological analysis. Hepatology. 2009;49:851–859. doi: 10.1002/hep.22734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shariff MI, Cox IJ, Gomaa AI, Khan SA, Gedroyc W, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current trends in worldwide epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and therapeutics. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:353–367. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel AB, Zhu AX. Metabolic syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma: two growing epidemics with a potential link. Cancer. 2009;115:5651–5661. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Zeuzem S, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, McGlynn KA. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: a study in the SEER-Medicare database. Hepatology. 2011;54:463–471. doi: 10.1002/hep.24397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]