Abstract

T-cells play an important role in host immunity against invading pathogens. Determining the underlying regulatory mechanisms will provide a better understanding of T-cell-derived immune responses. In this study, we have shown the differential regulation of IL-6 and CXCL8 by NF-κB and NFAT in Jurkat T-cells, in response to PMA, heat killed Escherichia coli and calcium. CXCL8 was closely associated with the activation pattern of NFAT, while IL-6 expression was associated with NF-κB. Furthermore, increasing the intracellular Ca2+ concentration by calcium ionophore treatment of the cells resulted in NFAT induction without affecting the NF-κB activity. Interestingly, NF-κB activation by heat killed E. coli, as well as CXCL8 and IL-6 expression was significantly suppressed following addition of the calcium ionophore. This indicates that calcium plays an important role in regulating protein trafficking and T-cell signalling, and the subsequent inflammatory gene expression infers an involvement of NFAT in CXCL8 regulation.Understanding these regulatory patterns provide clarification of conditions that involve altered intracellular signalling leading to T-cell-derived cytokine expression.

Keywords: Inflammation, PMA, E. coli., gene expression

Introduction

T-cells play a key role by acting as a link between innate and acquired immunity. It is therefore important to map the different regulatory mechanisms involved in T-cell activation. Nuclear factor (NF)-κB plays a prominent role in T-cells by regulating and initiating an inflammatory response [1], leading to cell proliferation, differentiation and survival of T-cells [2]. Furthermore, cytokine and chemokine expression also requires activator protein (AP)-1 and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) for optimal expression. Analysis of these intracellular regulatory mechanisms will help understand the role of T-cells in the initiation of an acquired immune response, following engagement of different antigens.

Studies of the complexity of signal transduction pathways in T-cells have identified a protein complex consisting of CARMA1 (caspase recruitment domain-containing membrane-associated guanylate kinase protein-1), Bcl10 (B-cell lymphoma 10) and MALT1 (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation protein 1) in the induction of NF-κB. Bcl10 is a critical regulator of NF-κB activity through signals transduced via the T-cell receptor (TCR)/CD28 and protein kinase C (PKC) [3]. It has been suggested that Bcl10 is initially activated by TCR/PKC and that prolonged activation (>1 h) promotes its degradation. Furthermore, deletion of any of the three proteins, CARMA1, Bcl10 and MALT1, has been shown to modulate antigen-receptor dependent activation of NF-κB [4]. NF-κB activation via Akt, which is located upstream of NF-κB, requires CARMA1 that acts in cooperation with PKC following short-term exposure of Jurkat T-cells with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA). Akt can also phosphorylate and activate Bcl10. Thus, CARMA1, Bcl10 and MALT1 play key roles in this signalling process. PMA, an analogue to diacylglycerol, diffuses into the cytosol where it directly activates PKC [5]. Inhibition of PKC blocks both NF-κB and AP-1 activity, suggesting a direct regulation of these transcription factors by PKC [6,7]. However, the activation of NFAT is strictly controlled by the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase, calcineurin [8]. It has been shown previously that this transcription factor forms complexes with Jun and Fos [9], which are essential for optimal gene expression, including IL-2 transcription.

Since its discovery, NF-κB has been shown to be an essential regulator of proliferation, differentiation and induction of inflammatory responses. The central role of NF-κB in these processes is therefore of particular interest as any modification in its signalling pathway may lead to an altered cellular response. We have shown earlier that PMA primarily acts through AP-1 to regulate CXCL8 and observed that there was a reduction of NF-κB activity following extended culturing and exposure to PMA [10]. The aim of the present study was to further analyse the effects of PMA and heat killed Escherichia coli on NF-κB and NFAT activation as well as the subsequent cytokine expression in Jurkat T-cells.

Materials and method

Cell culture conditions

Jurkat T-cells were maintained in 90% RPMI 1640 medium (PAA laboratories, Austria) with 1.5 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and incubated in a stable environment at 95% air, 5% CO2 and 37°C.

Heat killed Escherichia coli MG1655

E. coli MG1655 were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates and incubated at 37°C overnight. One colony was inoculated into 10 ml LB broth and the tube was incubated on shaker set at 200 rpm at 37°C overnight. The bacteria were then harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3000 ×g, washed with 3 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and re-suspended in 50 μl PBS. The bacteria were heated for 1 h at 70°C. To ensure that the bacteria were killed; 10 μl of the heat killed suspension was spread onto a LB plate and incubated overnight at 37°C. Colony forming units were determined prior to heating by serially diluting the culture in PBS and spread-plating onto LB agar. Bacterial concentrations of heat killed bacteria are reported as equivalent to CFU/ml.

Transfection and stimulation

The cells were centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 8 min and resuspended in fresh RPMI media to a final cell density of 5×106 cells/ml in a 24-well plate. Reporter plasmids NFAT-SEAP or pNF-κB-Luc, internal control plasmid Renilla (pRL; Promega, USA) and lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) were added to each well at 0.54 μg/well, 0.06 μg/well and 1.5 μl/well, respectively. Initially, reporter plasmid and pRL were mixed separately with OptiMEM (Gibco, USA). After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, lipofectamine 2000 was added and the mixture was incubated for a further 20 min at room temperature. The cells were transfected for 24 h at 37°C. Following transfection, the cells were centrifuged and fresh pre-warmed media was added. Stimulation was performed following the addition of PMA (Sigma, USA) or heat killed E. coli MG1655, in the presence or absence of the calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma C4159, USA).

Luciferase activity (NF-κB) was measured using Dual-Luciferase® reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). Secreted alkaline phosphatase (NFAT-SEAP) levels were measured using GreatEscAPeTM SEAP Detection Kit (Clonetech, USA). All the values were normalized to the internal Renilla control.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was performed on supernatants from challenged Jurkat T-cells to quantify IL-6 and CXCL8 (BD OptEIA Human IL-6 Elisa Set and BD OptEIA Human CXCL8 Elisa Set, Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, Jurkat T-cells were stimulated with PMA or heat killed E. coli for the indicated periods of time, centrifuged (1000 ×g, 8 min) and the supernatants were collected and stored at -80°C until use.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Results

Differential transcription factor activation and cytokine regulation

Cytokines and chemokines are regulated through distinct signalling pathways in response to foreign antigens. Analysis of these regulatory mechanisms is important to improve our understanding of diseases with altered cytokine and chemokine levels. In this study, we have determined IL-6 and CXCL8 regulation by NF-κB and NFAT in Jurkat T-cells in response to PMA and heat killed E. coli.

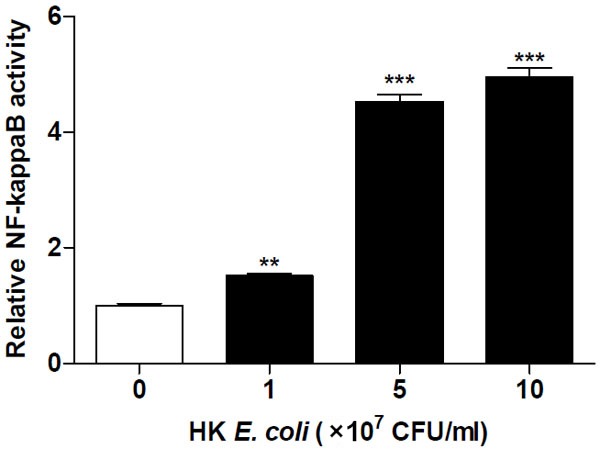

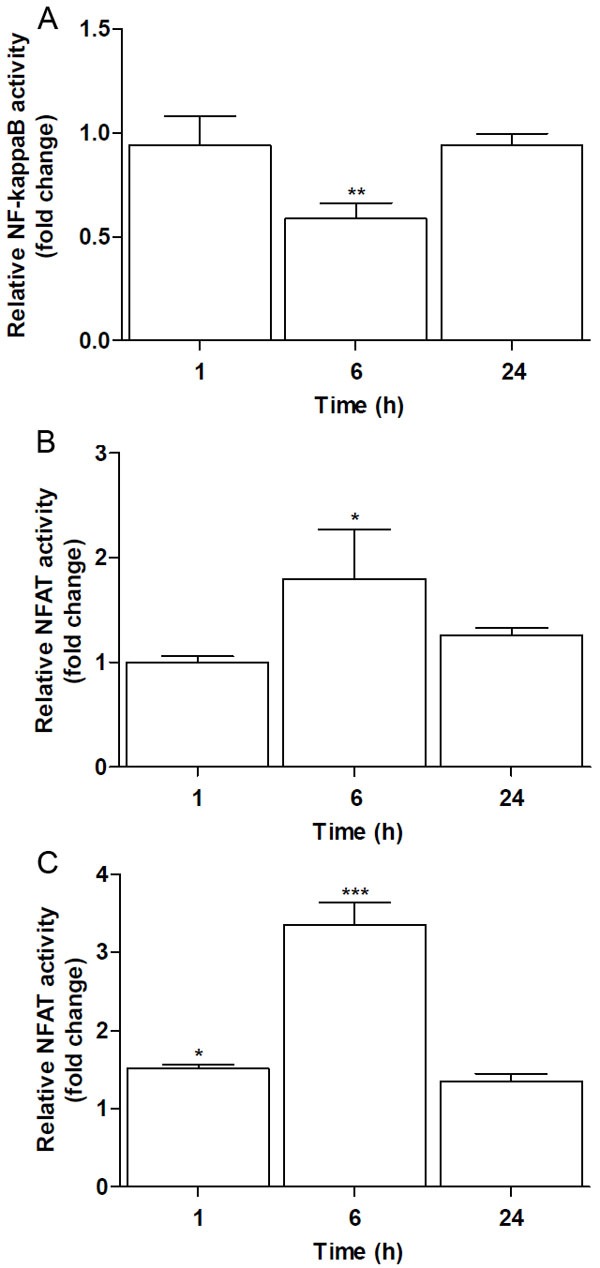

NF-κB activity in response to heat killed E. coli treatment resulted in a dose-dependent activation after 24 h of exposure (Figure 1). NF-κB activity increased ~1.5 fold at a relative bacterial concentration equivalent to 1×107 CFU/ml and continued to increase by ~5 fold following treatment with equivalent to 1×108 CFU/ml of heat killed E. coli. Furthermore, NF-κB and NFAT activities in Jurkat T-cells were analysed following exposure to PMA. We observed that PMA caused a significant reduction in NF-κB activity after 6 h, which returned to basal levels after 24 h (Figure 2A). In contrast, NFAT activity was significantly increased at 6 h, after which its activity was reduced to basal levels following 24 h of treatment (Figure 2B). Increased intracellular calcium has been reported to be a potent inducer of NFAT activation, through the calmodulin-calcineurin complex [11]. We therefore tested whether the introduction of a calcium ionophore would result in a time dependent NFAT activation. Stimulation of Jurkat T-cells with calcium ionophore A23187 resulted in a significant activation of NFAT after 1 h, which reached its maximum after 6 h and dropped thereafter to basal levels by 24 h (Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Heat killed E. coli activates NF-κB in a dose-dependent manner. NF-κB activity was determined in Jurkat T-cells transfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid after stimulation with increasing concentrations of heat killed E. coli MG1655 for 24 h. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n=4. Values were normalized against the internal Renilla control. Statistically significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (**p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 2.

PMA suppresses NF-κB and activates NFAT. Jurkat T-cells were transfected with NF-κB-luciferase or NFAT-SEAP reporter plasmids and the regulation of these transcription factors was determined following stimulation with 160 nM PMA after 1, 6 and 24 h. A. NF-κB, but not B. NFAT activity was suppressed by PMA. C. NFAT activity was increased in response to calcium Ionophore treatment (0.95 mM). Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n=4. Controls at each time point were arbitrarily set to 1. Values were normalized against the internal Renilla control. Statistically significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

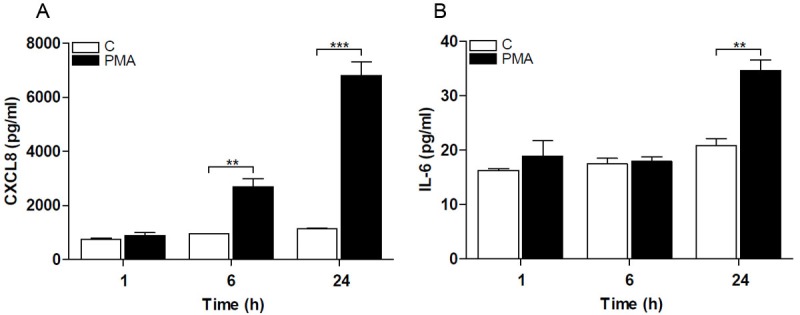

Optimal cytokine and chemokine expression is regulated by a cooperative induction of NF-κB, NFAT and other transcription factors including AP-1. The time-dependent differential activation of NF-κB and NFAT by PMA prompted us to evaluate the expression levels of IL-6 and CXCL8 following exposure to PMA. Stimulation of Jurkat T-cells with PMA resulted in a significant elevation of CXCL8 levels after 6 h with a further increase at 24 h (Figure 3A). In response to the same treatment the IL-6 levels remained at basal levels at 6 h but then increased by 24 h (Figure 3B). The CXCL8 and IL-6 levels were stable in the controls during the same times. These results show a differential regulation of cytokines by NF-κB and NFAT, which suggests a role for NFAT in CXCL8 expression.

Figure 3.

Cytokines are differentially regulated in Jurkat T-cells. Cytokine and chemokine release from Jurkat T-cells was determined after stimulation with 160 nM PMA. A. CXCL8 levels increased after 6 h and even further after 24 h, and B. IL-6 increased after 24 h. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n=4. Statistically significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (**p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

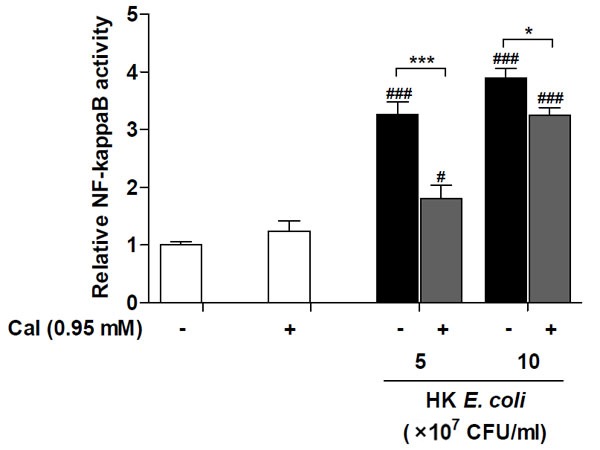

Calcium suppresses the induced NF-κB activation and cytokine expression

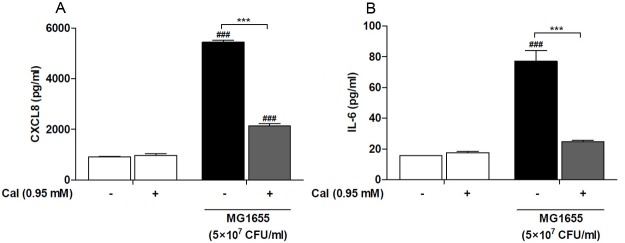

We analysed NF-κB regulation in response to increased intracellular calcium levels following treatment with heat killed E. coli. Jurkat T-cells were stimulated with two concentrations of heat killed E. coli, equivalent to 5×107 and 1×108 CFU/ml. The induction of NF-κB activation by heat killed E. coli was significantly reduced following addition of the calcium ionophore A23187 (Figure 4). Calcium ionophore treatment alone did not alter the basal level of NF-κB activity. This regulatory pattern prompted us to determine the cytokine and chemokine expression in response to heat killed E. coli treatment, following addition of the calcium ionophore. Treatment of Jurkat T-cells with equivalent to 5×107 CFU/ml of heat killed E. coli caused a significant induction of CXCL8 (Figure 5A) and IL-6 (Figure 5B), while exposure of cells to the calcium ionophore alone did not alter the levels of these inflammatory mediators. Increasing the intracellular calcium levels resulted in a significant reduction of both CXCL8 and IL-6 levels, to 60% and 68%, respectively. However, while the CXCL8 levels remained elevated above basal level, the IL-6 was suppressed to basal level. These results suggest that calcium is an important regulator of intracellular signalling and suggest that CXCL8 and IL-6 are differentially regulated in T-cells.

Figure 4.

Calcium ionophore suppresses the heat killed E. coli-induced NF-κB activation. Relative NF-κB activity was determined in Jurkat T-cells transfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid after treatment with the indicated equivalent concentrations of heat killed (HK) E. coli MG1655, with or without calcium ionophore (CaI) for 24 h. Values were normalized against the internal Renilla control. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n=4. Statistically significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (*/#p<0.05; ***/###p<0.001). #- significance from their respective negative control, HK E. coli stimulated groups were compared to the unstimulated control group (-), HK E. coli stimulated groups with addition of calcium ionophore were compared to the calcium ionophore control (+).

Figure 5.

Calcium ionophore suppresses cytokine and chemokine expression. Jurkat T-cells were stimulated with heat killed E. coli MG1655 equivalent to 5×107 CFU/ml, with or without the calcium ionophore (CaI), for 24 h followed by analysis of CXCL8 (A) and IL-6 (B) levels. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n=4. Statistically significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (***/###p<0.001). #- significance from their respective negative control, HK E. coli stimulated groups were compared to the control group (-), HK E. coli stimulated groups with addition of calcium ionophore cells were compared to the calcium ionophore control (+).

Discussion

NF-κB is a transcription factor specialized to respond to numerous diverse signals, including pathogens, environmental stress and endogenous signals [12,13]. Stimuli such as bacterial toxins, PMA or TNF result in an early and rapid activation of NF-κB in Jurkat T-cells followed by a drastic transcription of its inhibitory protein IκB [14]. NFAT activation is strictly regulated by the phosphatase calcineurin, which in turn is dependent on a sustained calcium influx [11]. In the present study we showed that CXCL8 and IL-6 are differentially regulated by NFAT and NF-κB and that the CXCL8 expression is closely associated with NFAT activity. NF-κB and NFAT activation, and subsequent CXCL8 and IL-6 expression, clarify these regulatory patterns in T-cells.

The involvement of NF-κB in human diseases, such as asthma, atherosclerosis and neurological disorders [15-17] has lead to the suggestion that it may be a potential therapeutic target [18,19]. Unravelling the mechanisms by which NF-κB induces inflammation, cell proliferation and cell survival has revealed complex signalling mechanisms that require further investigation. We found that NF-κB was suppressed by PMA after 6 h of exposure, while NFAT activity was significantly enhanced. This regulatory pattern of NF-κB has previously been shown to correspond for an early activation in response to PMA [12]. Since PMA is a potent activator of AP-1 [10] this may contribute to the observed NF-κB inhibition following long-term exposure to PMA in Jurkat T-cells. Previous studies aimed at investigating AP-1 and NF-κB regulation have shown that activated c-Jun acts as a negative regulator of NF-κB (p65) [20]. Suppression of PMA induced NF-κB activation may be mediated through PKC-dependent degradation of IKKβ and γ [12].

We observed that increased intracellular calcium induced NFAT activation without affecting NF-κB activity. Calcium is an important signalling molecule involved in the regulation of several intracellular pathways [21]. A second regulator of NF-κB activation is the Ca2+-dependent protein calmodulin, which inhibits c-Rel but allows RelA to translocate into the nucleus following activation [22]. The balance between apoptosis and survival is dependent on the levels of c-Rel and RelA. Chen and colleagues [23] showed that cytokine-induced apoptosis was elevated when RelA was depleted in embryonic fibroblasts, while depletion of c-Rel blocked apoptosis.

Induction of inflammatory mediators, including CXCL8, IL-6 and TNF is important for activation and differentiation of normal cells. These cytokines are also implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer cells by modulating growth conditions and angiogenesis [24]. The IL-6 release correlated well with the NF-κB activation pattern. The IL-6 levels were not elevated at 6 h, at which time NF-κB was suppressed by PMA, while NFAT activity was significantly induced. Secretion of IL-6 was enhanced after 24 h of exposure with PMA and NF-κB was re-activated, while NFAT activity dropped to basal levels. Furthermore, as CXCL8 levels remained stable in the controls over time, PMA exposure resulted in an elevation at 6 h, at which time NF-κB activity dropped to its lowest levels, while NFAT activity was enhanced. This expression pattern does not resemble that observed for NF-κB activity but rather presents a similar trend to NFAT activity and to our previous observations with AP-1 activity [10]. It has previously been shown that NFAT forms complexes with different subunits of the AP-1 family of transcription factors, and thus act synergistically to induce the expression of a wide range of inflammatory genes, including IL-2 and CXCL8 [25].

In the present study we showed that CXCL8 expression, but not IL-6, is closely associated with NFAT. These results indicate that there is an overlap between signalling pathways and thus reveal the complexity of intracellular communication systems that are directly connected to cellular responses. Evaluation of the links between these signalling cascades and determination of the regulatory pathways by which inflammatory genes are expressed is needed to improve our understanding of T-cell regulation in health and disease.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by The Knowledge Foundation and Sparbanksstiftelsen, Sweden. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ginn-Pease ME, Whisler RL. Optimal NF kappa B mediated transcriptional responses in Jurkat T cells exposed to oxidative stress are dependent on intracellular glutathione and costimulatory signals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:695–702. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aifantis I, Gounari F, Scorrano L, Borowski C, von Boehmer H. Constitutive pre-TCR signaling promotes differentiation through Ca2+ mobilization and activation of NF-kappaB and NFAT. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:403–409. doi: 10.1038/87704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scharschmidt E, Wegener E, Heissmeyer V, Rao A, Krappmann D. Degradation of Bcl10 induced by T-cell activation negatively regulates NF-kappa B signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3860–3873. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3860-3873.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narayan P, Holt B, Tosti R, Kane LP. CARMA1 is required for Akt-mediated NF-kappaB activation in T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2327–2336. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2327-2336.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebinu JO, Stang SL, Teixeira C, Bottorff DA, Hooton J, Blumberg PM, Barry M, Bleakley RC, Ostergaard HL, Stone JC. RasGRP links T-cell receptor signaling to Ras. Blood. 2000;95:3199–3203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry N, Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and T cell activation. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:205–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manicassamy S, Sadim M, Ye RD, Sun Z. Differential roles of PKC-theta in the regulation of intracellular calcium concentration in primary T cells. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horsley V, Pavlath GK. NFAT: ubiquitous regulator of cell differentiation and adaptation. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:771–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain J, McCaffrey PG, Miner Z, Kerppola TK, Lambert JN, Verdine GL, Curran T, Rao A. The T-cell transcription factor NFATp is a substrate for calcineurin and interacts with Fos and Jun. Nature. 1993;365:352–355. doi: 10.1038/365352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalaf H, Jass J, Olsson PE. Differential cytokine regulation by NF-kappaB and AP-1 in Jurkat T-cells. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park KA, Byun HS, Won M, Yang KJ, Shin S, Piao L, Kim JM, Yoon WH, Junn E, Park J, Seok JH, Hur GM. Sustained activation of protein kinase C downregulates nuclear factor-kappaB signaling by dissociation of IKK-gamma and Hsp90 complex in human colonic epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:71–80. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tergaonkar V. NFkappaB pathway: a good signaling paradigm and therapeutic target. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown K, Park S, Kanno T, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Mutual regulation of the transcriptional activator NF-kappa B and its inhibitor,I kappa B-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2532–2536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes P, Adcock I. NF-kappa B: a pivotal role in asthma and a new target for therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)89796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brand K, Page S, Walli AK, Neumeier D, Baeuerle PA. Role of nuclear factor-kappa B in atherogenesis. Exp Physiol. 1997;82:297–304. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattson MP, Meffert MK. Roles for NF-kappaB in nerve cell survival, plasticity, and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:852–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christman JW, Lancaster LH, Blackwell TS. Nuclear factor kappa B: a pivotal role in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and new target for therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:1131–1138. doi: 10.1007/s001340050735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renard P, Raes M. The proinflammatory transcription factor NFkappaB: a potential target for novel therapeutical strategies. Cell Biol Toxicol. 1999;15:341–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1007652414175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez-Perez I, Benitah SA, Martinez-Gomariz M, Lacal JC, Perona R. Cell stress and MEKK1-mediated c-Jun activation modulate NFkappaB activity and cell viability. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2933–2945. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonsson A, Hughes K, Edin S, Grundstrom T. Regulation of c-Rel nuclear localization by binding of Ca2+/calmodulin. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1418–1427. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1418-1427.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Kandasamy K, Srivastava RK. Differential roles of RelA (p65) and c-Rel subunits of nuclear factor kappa B in tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand signaling. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1059–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freund A, Jolivel V, Durand S, Kersual N, Chalbos D, Chavey C, Vignon F, Lazennec G. Mechanisms underlying differential expression of interleukin-8 in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:6105–6114. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macian F, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Rao A. Partners in transcription: NFAT and AP-1. Oncogene. 2001;20:2476–2489. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]