Abstract

Eukaryotic ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like systems play crucial roles in various cellular biological processes. In this work, we determined the solution structure of SAMP1 from Haloferax volcanii by NMR spectroscopy. Under low ionic conditions, SAMP1 presented two distinct conformations, one folded β-grasp and the other disordered. Interestingly, SAMP1 underwent a conformational conversion from disorder to order with ion concentration increasing, indicating that the ordered conformation is the functional form of SAMP1 under the physiological condition of H. volcanii. Furthermore, SAMP1 could interact with proteasome-activating nucleotidase B, supposing a potential role of SAMP1 in the protein degradation pathway mediated by proteasome.

Keywords: NMR, Haloferax volcanii, ubiquitin-like protein, SAMP1, protein folding

Introduction

Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls) play a crucial role as the post-translational modifiers in a series of cellular physiological regulation associated with protein degradation, cell apoptosis, transcription, DNA repair and so on.1,2 In eukaryotes, the ubiquitin system is involved in the conjugation between ubiquitin and substrates, which is activated by three classes of enzymes including activating enzyme (E1), conjugating enzyme (E2), and ligase (E3).2,3 Sequence and structure analysis shows that Ub and Ubls in eukaryotic cells are characterized by the C-terminal diglycine motif and the conserved β-grasp fold.4–7

In prokaryotes, it has been shown that a small prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis can tag the substrates for degradation, which is analogous to the ubiquitin in eukaryotes.8 However, recent study revealed Pup is intrinsically disordered and shares little sequence similarity with the eukaryotic counterparts except for the C-terminus.8–10 In addition, distinguished from ubiquitin, Pup has an additional glutamine at the C-terminus, which is deamidated by the deamidase Dop firstly when functioning. Subsequently, Pup is linked to the lysine residues of the substrates through an isopeptide bond and targets the substrates for degradation through proteasome pathway.8,10

Archaeabacterium are used to live in the extreme environment such as high salt concentration and high temperature. Recently, a proteasome system involved in the protein degradation has been revealed in Haloferax volcanii which grows best in the medium containing 0.5–2.5 M salt.11 Moreover, two ubiquitin-like small archaeal modifiers (SAMP1 and SAMP2) were discovered from Haloferax volcanii (H. volcanii).12 Although their sequences are less conserved compared with the ubiquitin-like proteins from eukaryotes and prokaryotes, they maintain the conserved C-terminal diglycine motif. Structural prediction implies that they might share a similar β-grasp fold with eukaryotic ubiquitin-like proteins.12 Furthermore, the SAMP1-modification patterns of proteasome-subunit deleted H. volcanii strains have been investigated, and the results demonstrated that SAMP1 might be involved in protein degradation.12 More recently, it has been discovered that SAMPs can modify proteins covalently and form polymeric chains.11

Here, we determined the solution structure of SAMP1 from archaeon Haloferax volcanii using NMR method. Surprisingly, we revealed that SAMP1 adopts two distinct conformations under low ionic condition and one of the conformations is dependent on ionic strength. Furthermore, we demonstrated that SAMP1 is able to interact with proteasome-activating nucleotidase B,13 supposing a potential role of SAMP1 in the protein degradation pathway via proteasome.

Results

SAMP1 displays two distinct conformations under low ionic condition

Sequence alignment of SAMP1 and eukaryotic and prokaryotic ubiquitin-like proteins showed that SAMP1 shares low sequence identity with the counterparts. Nevertheless, it possesses the conserved C-terminal diglycine motif, a characteristic of ubiquitin-like family proteins [Fig. 1(A)]. The recombinant SAMP1, containing 87 residues, [Fig. 1(A)], was expressed and purified. The purified SAMP1 was then dissolved in 25 mM NaH2PO4 and 0.1M NaCl at pH 6.7 for structural study. Surprisingly, under this condition, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of SAMP1 showed more than 160 resonances [Fig. 1(B)], implying that SAMP1 might adopt two distinct conformations. To test and verify the existence of two distinct conformations, a series of 3D NMR experiments were carried out to assign the resonances. As expected, two sets of resonances, representing two different conformations, were assigned [Fig. 1(B)].

Figure 1.

A: Multiple sequence alignment of SAMP1, SAMP2, Pup, ubiquitin and other β-grasp proteins. Alignment was performed with ClustalW2 26 and BOXSHADE version 3.2 (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html). Identical and similar amino acids are shaded in black and grey, respectively. HvSAMP1, Haloferax volcanii SAMP1; HvSAMP2, Haloferax volcanii SAMP2; HsUbiquitin, Homo sapiens Ubiquitin; HsUrm1, Homo sapiens Urm1; EcMoaD, Escherichia coli MoaD; EcThiS, Escherichia coli ThiS; MtPup, Mycobacterium tuberculosis Pup. B: 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of SAMP1 under low ionic condition (25 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 6.7), peaks of SAMP1-d are labeled with “*”. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Part of SAMP1 adopts the conserved β-grasp fold of eukaryotic ubiquitin-like proteins

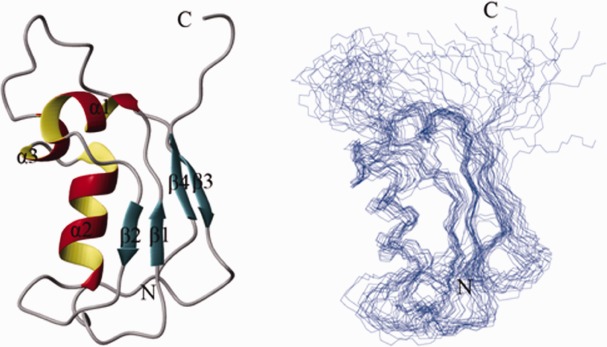

To further distinguish the secondary structure characteristics of two conformations of SAMP1, we performed the chemical shift index (CSI). The results showed SAMP1-o (the ordered form) contains four β-sheet and two α-helix while SAMP1-d (the disordered form) almost has no structured region except few residual secondary structure (Fig. 2). A series of 3D spectra were then carried out to obtain the solution structure of SAMP1-o. The minimum-energy solution structure of SAMP1-o and the assembly of twenty lowest-energy structures were shown in Figure 3. The statistics of the structure was shown in Table I.

Figure 2.

Chemical shift index (CSI) plots were tabulated based on chemical shifts of Hα, Cα, Cβ, CO of SAMP1 (upper for SAMP1-o, lower for SAMP1-d).

Figure 3.

Solution structures of SAMP1-o under low ionic condition. Ribbon structure of a representative conformer of SAMP1-o with the secondary structure elements highlighted (left) and ensemble of 20 lowest-energy conformers calculated for SAMP1-o (right). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Table I.

NMR and Structural Statistics of SAMP1-o Under Low Ionic Condition

| NMR restraints in the structure calculation | |

|---|---|

| Intraresidue | 167 |

| Sequential (|i - j| =1) | 285 |

| Medium-range (|i - j| <5) | 136 |

| Long-range (|i - j| >/=5) | 175 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 26 |

| Total distance restraints | 789 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | 95 |

| Lennard-jones potential energy, kcal mol−1 | −198.61 ± 17.15 |

| Rmsd from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds, Å | 0.0028 ± 0.0002 |

| Angles, ° | 0.3587 ± 0.0086 |

| Impropers, ° | 0.1860 ± 0.0092 |

| Rmsd from experimental restraints | |

| Distance, Å | 0.0107 ± 0.0012 |

| Constrained dihedral, ° | 0.1195 ± 0.0410 |

| Chemical shift assignment % | |

| Backbone | 88 |

| Total | 85 |

| Coordinate rmsd for residues 2–80, Å | |

| All backbone atoms | 1.99 |

| All heavy atoms | 2.68 |

| Coordinate rmsd for secondary structure, Å | |

| All backbone atoms | 1.11 |

| All heavy atoms | 1.65 |

| Ramachandran plot, % residues | |

| Most favored regions | 73.3 |

| Additionally allowed regions | 23.7 |

| Generously allowed regions | 1.8 |

| Disallowed regions | 1.2 |

SAMP1-o contains four β-strands and three α-helices. Strand 1 (residues 2–3), strand 2 (residues 17–19), strand 3 (residues 59–61), and strand 4 (residues 76–80) constitute a β-sheet at one side of the structure. The three helices, that is, α1 (residues 7–13), α2 (residues 28–37), and α3 (residues 40–43), pack together at the other side. In eukaryotes, ubiquitin-like proteins all have conserved β-grasp structures, which are folded compactly and maintained by the hydrophobic core formed by a β-sheet and one α-helix. On one hand, SAMP1-o adopts a similar β-grasp fold with the eukaryotic ubiquitin-like proteins. On the other hand, due to the existence of many flexible loops and the lack of more restraints between the secondary structures, the whole structure of SAMP-o is looser compared with other ubiquitin-like proteins.

SAMP1 presents a disordered state as well

CSI for the other conformation of SAMP1 indicated it is disordered with little structured region (Fig. 2). To further substantiate the existence of the disordered conformation, we measured 15N longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times and heteronuclear {1H}-15N NOE, which could provide valuable information for the motional dynamics of the protein. The results showed that the average T1 of SAMP1-d was a little higher than that of SAMP1-o (see Supporting Information Fig. S1A), while, the T2 of SAMP1-d were 1.5 to 3 times of those of SAMP1-o (see Supporting Information Fig. S1B). Besides, a number of the heteronuclear NOEs of SAMP1-d were negative, indicating that most of the polypeptide chain of SAMP1-d adopted large amplitude fluctuations on a subnanosecond time scale (see Supporting Information Fig. S1C). These suggested SAMP1-d was more flexible, supporting it is disordered. The structural constraints of SAMP1-d were also extracted out from 3D 15N-NOESY spectra to dig more structural information. No medium-range and long-range NOEs but only short-range NOE constraints were obtained in SAMP1-d (see Supporting Information Fig. S1D), further confirming the disordered property of SAMP1-d.

The disordered conformation converts to ordered one with the increase of salt concentration

We confirmed the coexistence of ordered and disordered conformations under low salt condition. However, for Haloferax volcanii, halophilic archaeon, high salt is required for their growth and physiological function in vivo. To better understand the structure of SAMP1 under its physiological conditions, we recorded a series of 1H-15N-HSQC spectra of SAMP1 in different concentrations of salts ranging from 0.1M to 3M. Interestingly, with the salt concentration increased from 0.1M to 1M, a considerable proportion of the resonances of SAMP1-d were seriously weakened, some even disappeared (Fig. 4). By contrast, all the resonances of SAMP1-o were maintained when the salt increasing. This observation indicated that SAMP1 underwent a conformational conversion from disorder to order with the increase of ion concentration. The HSQC spectra of SAMP1 in 2M and 3M NaCl were similar to that in 1M NaCl (Fig. 4), indicating that the concentration of NaCl higher than 1M had little influence on the state of SAMP1.

Figure 4.

15N-HSQC spectra of SAMP1 in different salt concentrations. The salt concentrations are 0.1M, 1M, 2M, and 3M of NaCl, respectively. Note that all the weakened and disappeared resonances of SAMP1 belong to the disordered conformation and are distributed between 8.0 and 8.7 ppm of HN. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The disordered conformation is a nature of SAMP1 under low ionic condition

We indicated that SAMP1 adopts both disordered and ordered conformations under low ionic condition. However, one question is whether the disordered conformation of SAMP1 under low ionic condition is its nature or merely an artifact or contamination produced during the process of expression or purification. To answer the question, we obtained 1H-15N HSQC spectrum for SAMP1 in 1M NaCl, then diluted it to 0.1M NaCl by dialysis and recorded another spectrum. As expected, the spectrum showed only resonances of the ordered conformation in 1M NaCl (Fig. 5). While, in the spectrum in diluted 0.1M NaCl, additional resonances, which were identified from the disordered conformation, appeared besides of those of the ordered conformation (Fig. 5). This verified that the disordered conformation is a nature of SAMP1 under low ionic condition.

Figure 5.

15N-HSQC spectra of SAMP1 in different salt concentrations from high to low ionic salt concentration. 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of SAMP1 under 1M NaCl. 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of SAMP1 under 0.1M NaCl which is dialyzed from SAMP1 under 1M NaCl. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

SAMP1 could interact with proteasome subunit, PanB

As a proteasome subunit in H. volcanii, proteasome-activating nucleotidase B (PanB) can be recognized by ubiquitin conjugated substrates and plays an important role in protein degradation.13 In the present study, the N terminus of PanB (residues 1−74), which was predicted to adopt coiled-coil conformation and involved in substrate recognition, was cloned, overexpressed, and purified. Chemical shift perturbation experiment was then performed to detect possible interactions between SAMP1 and PanB by recording 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 15N-labeled SAMP1 in 1M NaCl before and after addition of increasing amounts of unlabeled PanB.

As indicated by the series of HSQC spectra, SAMP1 was able to interact with PanB, evidenced by the changes of some resonances after addition of PanB [Fig. 6(A,B)]. After the addition of PanB, the obvious changed chemical shifts of resonances include L5, A7, D8, A10, E11, N58, N62, G63, E64 (see Supporting Information Fig. S2). The perturbed residues, supposed to be responsible for the interactions between SAMP1 and PanB, are distributed mostly in the two helices and loop region (see Supporting Information Fig S3). Analysis of the ligand-concentration dependence of the chemical shift changes induced by PanB derived a dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.75 mM for the interaction [Fig. 6(C)]. Furthermore, the interactions between SAMP1 and PanB were further confirmed by ITC experiment. The dissociation constant (Kd) was about 0.48 mM which consists with that generated from chemical shift perturbation experiment (Fig. 7). Both of these two assays indicated that the interaction affinity between SAMP1 and PanB is relatively weak. It is possible that avid binding needs the formation of a SAMP1 chain similar to some cases observed in ubiquitin system.14 The residues of SAMP1 in low salt concentration involved in the interaction with PanB were from its ordered conformation, similar to in high salt concentration (see Supporting Information Fig. S4). Thus, under different ionic conditions, SAMP1 interacted with PanB through a same pattern. This finding indicated that SAMP1 probably is the ubiquitin-like protein in H. volcanii which could be recognized by proteasome ATPase subunit PanB and involved in protein degradation by proteasome.

Figure 6.

A: 1H-15N HSQC spectra of SAMP1 titrated with unlabeled PanB under high ionic condition at various molar ratios. B: The selected residues of SAMP1 with chemical shift or peak intensity significantly changed in the perturbation. Red (1:0), blue (1:2) and green (1:4). C: Plots of the chemical shift changes of three well-resolved amide resonances against PanB concentrations. Each dissociation constant is determined by fitting the data to a single-site ligand-binding model. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 7.

The interactions between SAMP1 and PanB measured by ITC assay. The cell contains 250 µL 50 µM SAMP1 and syringe contains 60 µL 2 mM PanB (upper panel). The lower panel shows the heat differences obtained from 20 injections of PanB after baseline correction and the integrated binding curve is generated according to the one site binding model.

Discussion

Halophilic archaea or haloarchaea have been developed into model organisms that are used to study many biological processes.15 In this study, we revealed that SAMP1, a post-translational protein modifier from Haloferax volcanii, presents two conformations, an ordered and a disordered, under low ionic conditions. The ordered conformation adopts the β-grasp fold which is the characteristics of the ubiquitin-like proteins from eukaryotes, while the disordered one is similar to that of the prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein, Pup. Moreover, our results confirmed that the disordered conformation and the coexistence of the two conformations are natures of SAMP1 under low ionic conditions.

As we know, Haloferax volcanii lives in high salt environments. There arises the question that which conformation SAMP1 adopts to be adapted to the extreme physiological conditions. Our study revealed that the two conformations of SAMP1 would transform to a single conformation, the ordered one, with the increase of ion concentration. This supposes that the ordered conformation is the functional form of SAMP1 under the physiological conditions.

A proteasome complex has been discovered in Haloferax volcanii, which suggests the existence of a protein degradation pathway similar to the ubiquitin system in eukaryotes and the Pup pathway in prokaryote.16 In our study, we revealed that SAMP1 is able to, via the ordered conformation, interact with proteasome ATPase subunit PanB, confirming the functional role of the form. In addition to the previous study that detected a substantial increase in SAMP1-conjugate in proteasome ATPase subunit mutant strains,12 these imply that SAMP1 might be the ubiquitin-like protein involved in protein degradation mediated by proteasome in Haloferax volcanii.

According to the structural features of ubiquitin-like family proteins, the discovery of the two conformations of SAMP1 might provide an evolutionary link between the ubiquitin-like proteins in eukaryotes and Pup in prokaryotes. As SAMP1 in low concentrations of salt presents both the folded conformation like those of eukaryotic ubiquitin-like proteins and the disordered form similar to that of prokaryotic Pup, it may represent an ancestor of the ubiquitin-like proteins and imply two potential evolution pathways for ancient extremophile organisms to be adapted to the mild environments on the modern earth. In one of the two pathways, the proteins evolved to maintain the functional folded form while lost the non-functional disordered one, like ubiquitin in eukaryotes. In the other pathway, the proteins evolved to function through the disordered form while lost the ordered one, like Pup in prokaryotes. A detailed evolutionary analysis (data not shown) on ubiquitin-like family proteins demonstrated that, in evolution, SAMP1 is closer to MoaD, ThiS, and Urm1, which are thought to be ancestors of ubiquitin-like superfamily.17,18

Materials and Methods

Protein preparation

SAMP1 full length gene was amplified and cloned into NdeI/XhoI site of pET-22 b (+) (Novagen). The recombinant was transformed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) and expressed in Luria-Bertanimedium (LB) inducing with 0.5 mM isopropyl -β-D- thiogalacto- pyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h until the cell OD600 of 0.8. Then the purified steps were carried out according to the previous procedures.10 15N, 13C-labeled SAMP1 was purified in the same way except that super broth was replaced by M9 medium.

NMR experiments and structure calculation

The NMR sample was prepared in a phosphate buffer comprising 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 6.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA with 10% (v/v) of 2H2O. The NMR spectra for structure calculation were recorded at 293 K on a Bruker DMX500 spectrometer. All the NMR data were processed with NMRpipe and analyzed with Sparky 3 software. 1H-15N HSQC, 3D CBCA (CO) NH, 3D CBCANH, 3D HNCO, 3D HN (CA) CO, 3D C (CO) NH-TOCSY, 3D H (CCO) NH-TOCSY, 3D 15N-TOCSY, 3D HCCH-TOCSY, 3D HCCH-COSY, 3D HBHA (CACBCO) NH spectra were recorded for backbone and side chain assignment. 3D 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY spectra were used for obtaining distance restrains. Then a series of 15N-HSQC experiments were performed used for obtaining hydrogen bond restrains in which sample was dissolved in 99.96% (v/v) 2H2O. Dihedral restraints (Φ/Ψ) were obtained with TALOS software.19 Hydrogen bond restraints were obtained by assignment of slow-exchange amide protons located in regular secondary structural elements (SSEs). The CNS program20–22 was used to calculate 3D structure by distance restraints by the method of ARIA setup and protocols. Short-range NOEs and long-range NOEs were obtained first and used to determine SSEs of SAMP1. Then φ and ψ backbone dihedral angles and hydrogen bond restraints were acquired and added in to constraint 3D structure. Two hundred structures were calculated and the final 20 structures with lowest energy were generated and analyzed with MOLMOL.23 Ramachandran plot was carried out with PROCHECK24 to judge the quality of the structure.

15N longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times and the heteronuclear 1H-15N NOE spectra were recorded on Bruker DMX600 spectrometer at 293 K. 8 time points with delays of 11.15, 61.30, 141.54, 241.84, 362.20, 522.68, 753.37, and 1144.54 ms were collected for the T1 measurements; For T2 value, 7 time points with delays of 0, 17.6, 35.2, 52.8, 70.4, 105.6, and 140.8 ms were collected. The heteronuclear 1H-15N NOE was obtained from duplicate pairs of 1H-15N spectra recorded with and without amide proton saturation.

Chemical shift perturbation

0.3 mM 15N-labeled SAMP1 was titrated with unlabeled N terminus of PanB separately and a series of 15N-HSQC spectra were recorded for each molar ratio at 293 K. A concentration gradient consisting of three molar ratios (SAMP1:PanB = 1:0, 1:2, 1:4) was used in each perturbation assay. Combined chemical shift perturbation was calculated using standard method.25

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

The interaction between SAMP1 and PanB was carried out with ITC (ITC200, GE Company) at 20–. SAMP1 and PanB were purified and dialyzed to 20 mM KH2PO4, 1M KCl, 1 mM EDTA at pH 6.7. The concentration of SAMP1 and PanB was 50 µM and 2 mM, respectively. 250 µL SAMP1 was loaded in the cell and 60 µL PanB was loaded in the syringe. The titration was performed as follows: 20 injections of 2 µL with a stirring speed of 1000 rpm and with a delay time of 2 min between injections. The data was analyzed by MicroCal LLC ITC software (MicroCal).

Accession code

PDB: Worldwide Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 2L83)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank F. Delaglio and A. Bax for providing NMRPipe and NMRDraw, T. D. Goddard, and D. Kneller for Sparky, T. Brünger for CNS, R. Koradi and K. Wuthrich for MOLMOL.

Supplementary material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Hochstrasser M. Origin and function of ubiquitin-like proteins. Nature. 2009;458:422–429. doi: 10.1038/nature07958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris JR. More modifiers move on DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3861–3863. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas AL, Siepmann TJ. Pathways of ubiquitin conjugation. FASEB J. 1997;11:1257–1268. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.14.9409544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka K, Suzuki T, Chiba T. The ligation systems for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Mol Cells. 1998;8:503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burroughs AM, Balaji S, Iyer LM, Aravind L. A novel superfamily containing the beta-grasp fold involved in binding diverse soluble ligands. Biol Direct. 2007;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iyer LM, Burroughs AM, Aravind L. The prokaryotic antecedents of the ubiquitin-signaling system and the early evolution of ubiquitin-like β-grasp domains. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M. Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:159–180. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearce MJ, Mintseris J, Ferreyra J, Gygi SP, Darwin KH. Ubiquitin-like protein involved in the proteasome pathway of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science's STKE. 2008;322:1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1163885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao S, Shang Q, Zhang X, Zhang J, Xu C, Tu X. Pup, a prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein, is an intrinsically disordered protein. Biochem J. 2009;422:207–215. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutter M, Striebel F, Damberger FF, Allain FHT, Weber-Ban E. A distinct structural region of the prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) is recognized by the N-terminal domain of the proteasomal ATPase Mpa. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3151–3157. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darwin KH, Hofmann K. SAMPyling proteins in archaea. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:348–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humbard MA, Miranda HV, Lim JM, Krause DJ, Pritz JR, Zhou G, Chen S, Wells L, Maupin-Furlow JA. Ubiquitin-like small archaeal modifier proteins (SAMPs) in Haloferax volcanii. Nature. 2010;463:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature08659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuter CJ, Kaczowka SJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Differential regulation of the PanA and PanB proteasome-activating nucleotidase and 20S proteasomal proteins of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7763–7772. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7763-7772.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miranda HV, et al. E1-and ubiquitin-like proteins provide a direct link between protein conjugation and sulfur transfer in archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4417–4422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018151108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou G, Kowalczyk D, Humbard MA, Rohatgi S, Maupin-Furlow JA. Proteasomal components required for cell growth and stress responses in the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:8096–8105. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson HL, Aldrich HC, Maupin-Furlow J. Halophilic 20S proteasomes of the Archaeon Haloferax volcanii: purification, characterization, and gene sequence analysis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5814–5824. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5814-5824.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochstrasser M. Evolution and function of ubiquitin-like protein-conjugation systems. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:153–157. doi: 10.1038/35019643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Zhang J, Wang L, Zhou J, Huang H, Wu J, Zhong Y, Shi Y. Solution structure of Urm1 and its implications for the origin of protein modifiers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11625–11630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604876103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linge J, Nilges M. Influence of non-bonded parameters on the quality of NMR structures: a new force field for NMR structure calculation. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:51–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1008365802830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilges M, O'Donoghue SI. Ambiguous NOEs and automated NOE assignment. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 1998;32:107–139. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskowski RA, Rullmann JAC, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen W, Xu C, Huang W, Zhang J, Carlson JE, Tu X, Wu J, Shi Y. Solution structure of human Brg1 bromodomain and its specific binding to acetylated histone tails. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2100–2110. doi: 10.1021/bi0611208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larkin M, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.