Abstract

Background & Aims

Patients treated with surgery for colorectal cancer (CRC) should undergo colonoscopy examinations 1, 4, and 9 years later, to check for cancer recurrence. We investigated the utilization patterns of surveillance colonoscopies among Medicare patients.

Methods

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)–Medicare linked database to identify patients who underwent curative surgery for colorectal cancer from 1992 to 2005 and analyzed the timing of the first 3 colonoscopies after surgery. ‘Early surveillance colonoscopy’ was defined as a colonoscopy, for no reason other than surveillance, within 3 months to 2 years after a colonoscopy examination with normal results.

Results

Approximately 32.1% and 27.3% of patients with normal results from their first and second colonoscopies, respectively, underwent subsequent surveillance colonoscopies within 2 years (earlier than recommended). Of patients who were more than 80 years old at their first colonoscopy, 23.6% underwent a repeat procedure within 2 years for no clear indication. In multivariable analysis, early surveillance colonoscopy was not associated with sex, race, or patients’ level of education. There was significant regional variation in early surveillance colonoscopies among the SEER regions. There was a significant trend toward reduced occurrence of 2nd early surveillance colonoscopies.

Conclusion

Many Medicare enrollees who have undergone curative resection for colorectal cancer undergo surveillance colonoscopy more frequently than recommended by the guidelines. Reducing overuse could free limited resources for appropriate colonoscopy examinations of inadequately screened populations.

Keywords: prevention, early detection, colon cancer screening, cost efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is third most common cancer in the United States. In 2012, estimated −143,460 patients will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer.1 In 76% of these, the disease will be either localized or extending to the regional lymph nodes, qualifying them for curative resection.2, 3 Around 30–40% of patients will develop recurrent colorectal cancer after curative surgery.2, 4, 5 Studies show that surveillance colonoscopy identifies early recurrences at a stage that allows curative treatment.6–11 Hence, the American Cancer Society, American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) and the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer all recommend surveillance colonoscopy in patients who have undergone curative resection of colorectal cancer.11 The current guidelines call for patients to undergo their first surveillance colonoscopy at one year after the surgery. If the colonoscopy is normal, the next colonoscopy should be performed after three years and then every five years.11 The guidelines of gastroenterology and oncology societies for colorectal cancer surveillance have been changing during the past decade. Table 1 summarizes the guidelines recommended by various societies in the last few years.12–14

Table 1.

Guidelines for duration between surveillance colonoscopy.

| Society | Recommendation* |

|---|---|

| American Gastroenterology Association (1997) | 1 year, then every 3 years |

| American Society of Clinical Oncology (2000) | every 3–5 years |

| American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (2004) | every 3 years |

| US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (2006) | 1 year, after 3 years and then every 5 years |

In these recommendations, the intervals between the colonoscopy procedures are based on the assumption that the previous procedure was normal.

Some attention has been paid to underutilization of surveillance colonoscopy in the United States.15–19 For example, Cooper et al. showed that only 73.6 % of patients with colorectal cancer who underwent surgery with curative intent received one surveillance colonoscopy within three years.15 By contrast, data on overutilization of surveillance colonoscopy is limited. Studying overutilization of surveillance of colonoscopy is important because colonoscopy is an invasive test with rare but potentially life-threatening complications.20–22 Overuse of colonoscopy can lead to increased toxicities without added benefit. Second, colonoscopy is a limited resource, in terms of facilities and practitioners.23, 24 Identifying and decreasing overutilization of surveillance colonoscopy should free up resources for greater use in inadequately screened populations.

The objective of this study is to describe the utilization patterns of surveillance colonoscopy in Medicare patients who underwent curative resection of colorectal cancer during 1992–2005. In this article, we focus on the potential overutilization of surveillance colonoscopy in this setting, in particular the use of colonoscopy at shorter intervals than recommended.

METHODS

Data Source

We used the SEER-Medicare linked database. The SEER-Medicare data links two large population-based sources of detailed information about Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. The data came from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of cancer registries that collect clinical, demographic and cause of death information for persons with cancer and the Medicare claims for covered health care services from the time of a person's Medicare eligibility until death. Since 2000, SEER programs were expanded to 16 registries that represent 28% of the United States population.

Study Subjects and Outcome

We formed a cohort of patients aged 66 years and above diagnosed with colorectal cancer during 1992–2005. We included those diagnosed with AJCC Stages 1–3 colorectal cancer. Patients with a history of inflammatory bowel disease were excluded. We studied the pattern of receipt of the first three colonoscopies after curative surgery in this cohort. To ensure complete information, we excluded patients who were not enrolled in both Part A and B and were members of a health maintenance organization (HMO) for the period under observation. In the analyses of surveillance colonoscopy, we limited our study cohorts to patients diagnosed in 1992–2003 for the 2nd colonoscopy and in 1992–2002 for the 3rd colonoscopy.

We examined the indications for colonoscopy using the diagnosis on the colonoscopy claim (provided in Appendix). We considered the colonoscopies as indicated if the diagnosis was anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding or other relevant diagnosis like change in bowel habits, weight loss, abdominal pain or colostomy problems. If a barium enema or computed tomography of the abdomen or pelvis was performed in the three months before the colonoscopy, we also considered the colonoscopy as indicated. A ‘diagnostic colonoscopy’ was defined as one performed to evaluate a clinical indication or done after radiology. We used the term ‘surveillance colonoscopy’ to refer to procedures done with no clinical indication or evidence of prior radiology. We used the term ‘any colonoscopy’ to refer collectively to both diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopies.

Table 1 summarizes the guidelines of various authorities of the optimal time between surveillance colonoscopies in patients who had undergone curative resection of colorectal cancer.12–14 Some of the recommendations changed during the study period (1992–2005). The minimum duration for the second surveillance colonoscopy in all these guidelines is three years after a normal first colonoscopy, and the minimum duration for a third surveillance colonoscopy was 3–5 years after a normal second colonoscopy. Hence, we defined any second or third surveillance colonoscopy performed any time from three months to two years after the previous normal colonoscopy as early surveillance colonoscopy. We defined a normal colonoscopy as one not associated with any procedure like polyp removal, biopsy or any other procedure.

Covariates

Demographic data were collected on age, race, socioeconomic variables and SEER geographic region. Race was divided into White, Black, Hispanic and Other according to the SEER race code classification. For patients diagnosed during 1992–1995, education was defined as the proportion of adults who did not complete high school by census tract, based on the 1990 US Census; for patients diagnosed during 1996–2002, the 2000 US Census was used. Cancer characteristics were taken from SEER data files. Information was collected on AJCC stage (Stage 1, 2 and 3) and grade (well, moderately and poorly differentiated). Comorbidity was assessed using Klabunde's adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index. Higher scores indicate more comorbidity. This analysis required Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims in the 12 months before the diagnosis of colorectal cancer; therefore, we limited our analysis to subjects ≥ 66 years. Data on physician experience was based on the number of years since their graduation year and was obtained from AMA linkage file. Physician specialty was obtained from Medicare part B claims.

Statistical Analysis

The rate of any colonoscopy following a normal colonoscopy was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Beneficiaries were censored at death, loss of coverage or end of follow-up (12/31/2006).Multivariate analysis of receipt of early surveillance colonoscopy without indications was performed using a modified Poisson regression model. Patients without two full years of follow-up after the first or second colonoscopy were excluded from analyses of early surveillance colonoscopy. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

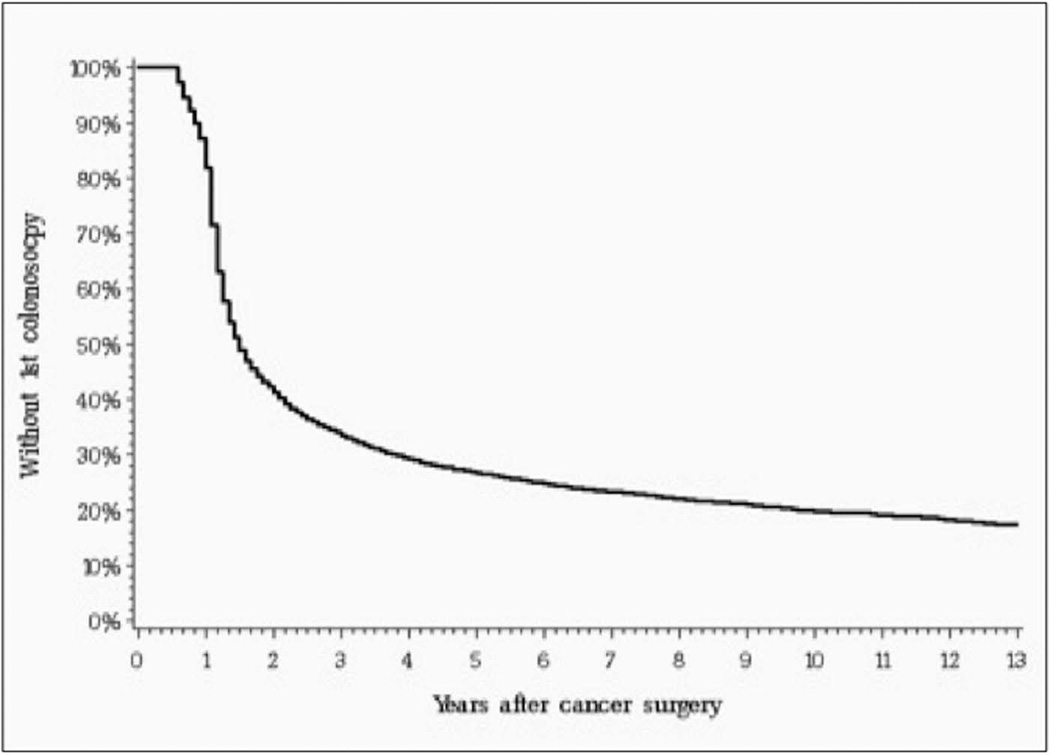

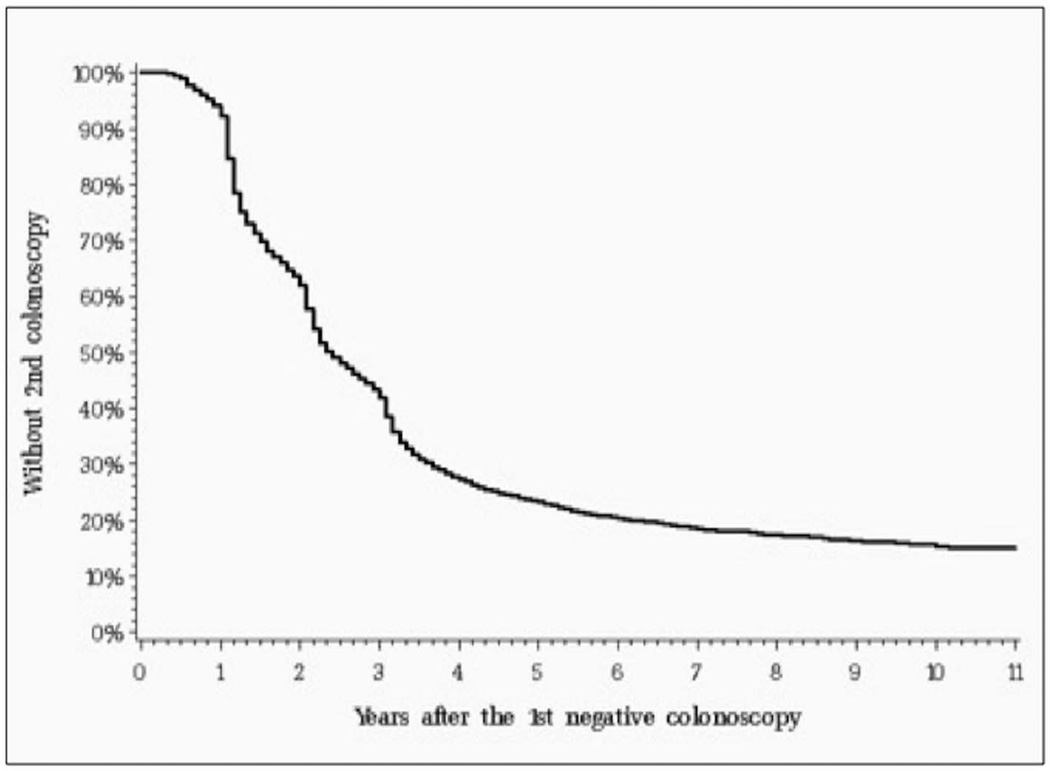

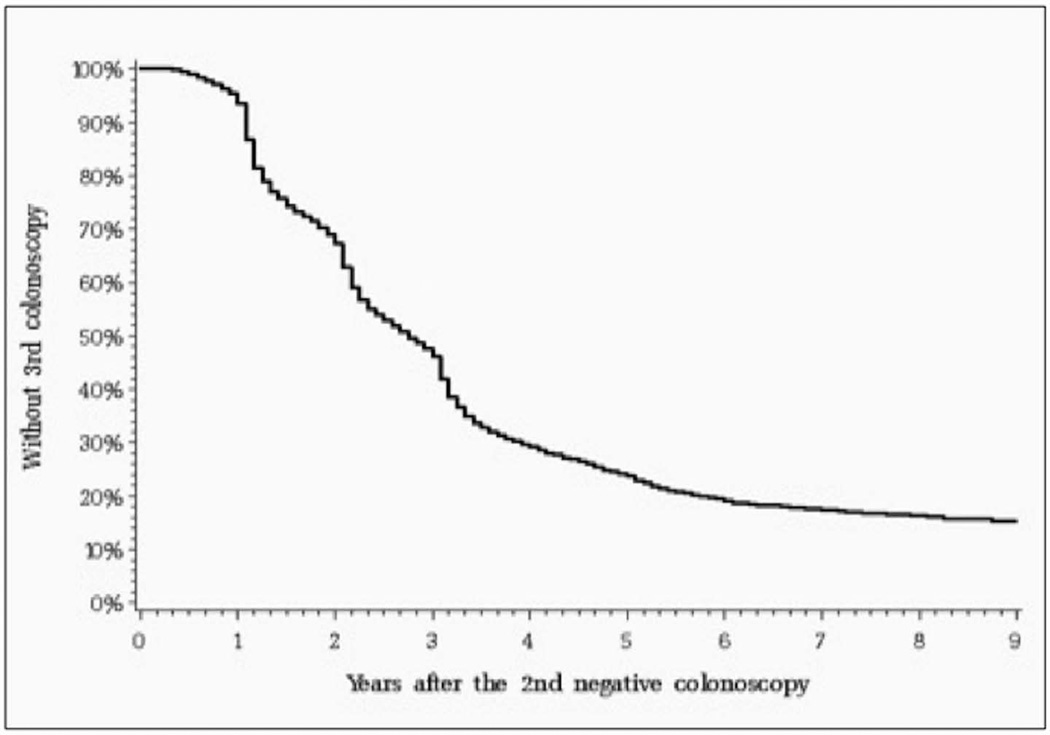

Table 2 shows the characteristics of our initial study cohort. We then used the Kaplan Meier method to estimate time to follow-up colonoscopies. Figure 1A shows the time from surgery to any initial colonoscopy, either diagnostic or surveillance. Similarly, Figures 1B and 1C show the time to any second and third colonoscopy in patients who underwent a normal first or second colonoscopy, respectively. Two findings are apparent. First, approximately 17.5% of patients never undergo a first surveillance colonoscopy, and an additional 14.8% of patients with a normal first colonoscopy do not undergo subsequent colonoscopies. Second, Figure 1B shows that a substantial proportion of patients undergo follow up colonoscopy within two years after their first normal colonoscopy, with a similar pattern shown in Figure 1C for patients after their second normal colonoscopy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients who underwent curative surgery for colorectal cancer during 1992–2005.

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 70419 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 67 – 69 | 10754 | 15.3 |

| 70 – 74 | 16465 | 23.4 | |

| 75 – 79 | 17713 | 25.2 | |

| >= 80 | 25487 | 36.2 | |

| Gender | Male | 31895 | 45.3 |

| Female | 38524 | 54.7 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 59860 | 85.0 |

| Black | 4541 | 6.4 | |

| Hispanic | 2663 | 3.8 | |

| Others | 3355 | 4.8 | |

| SEER Regions | Connecticut | 7178 | 10.2 |

| Detroit | 7444 | 10.6 | |

| Hawaii | 1213 | 1.7 | |

| Iowa | 8706 | 12.4 | |

| New Mexico | 1867 | 2.7 | |

| Seattle | 4624 | 6.6 | |

| Utah | 1873 | 2.7 | |

| Atlanta/Rural Georgia | 2567 | 3.6 | |

| Kentucky | 4015 | 5.7 | |

| Louisana | 3210 | 4.6 | |

| New Jersery | 8305 | 11.8 | |

| California | 19417 | 27.6 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 36345 | 51.6 |

| Not Married | 34074 | 48.4 | |

| Census Track education (% adult less than 12 years education) | < 9.1% | 16246 | 23.4 |

| 9.1 – < 15.3% | 17032 | 24.5 | |

| 15.3 – < 23.4% | 16712 | 24.0 | |

| >= 23.4% | 19580 | 28.1 | |

| Census Track poverty (% adults below the poverty line) | < 4.1% | 15389 | 22.1 |

| 4.1 – < 7.7% | 16442 | 23.6 | |

| 7.7 – < 15.1% | 17168 | 24.7 | |

| >= 15.1% | 20571 | 29.6 | |

| Comorbidity | 0 | 61982 | 88.0 |

| 1 | 5209 | 7.4 | |

| 2 | 1865 | 2.6 | |

| >=3 | 1363 | 1.9 | |

| Year of diagnosis | 1992 | 3839 | 5.5 |

| 1993 | 3500 | 5.0 | |

| 1994 | 3581 | 5.1 | |

| 1995 | 3421 | 4.9 | |

| 1996 | 3435 | 4.9 | |

| 1997 | 3413 | 4.8 | |

| 1998 | 3569 | 5.1 | |

| 1999 | 3333 | 4.7 | |

| 2000 | 7295 | 10.4 | |

| 2001 | 7247 | 10.3 | |

| 2002 | 7198 | 10.2 | |

| 2003 | 7213 | 10.2 | |

| 2004 | 6774 | 9.6 | |

| 2005 | 6601 | 9.4 | |

| AJCC stage | 1 | 21052 | 29.9 |

| 2 | 27680 | 39.3 | |

| 3 | 21687 | 30.8 | |

| Grade | Well | 6604 | 9.4 |

| Moderate | 47510 | 67.5 | |

| Poor | 12678 | 18.0 | |

| Unknown | 3627 | 5.2 | |

Figure 1.

A. Time of first colonoscopy among patients who underwent curative surgical resection (N=70,419). This graph includes patients who underwent first colonoscopy for any indication (either surveillance or diagnostic). The median time between surgery and first surveillance colonoscopy was 18 months (25th–75th percentile 13–72 months).

B. Time of second surveillance colonoscopy after the first normal colonoscopy for 19,969 patients. This graph includes patients who underwent second colonoscopy for any indication (either surveillance or diagnostic). The median time between first and second surveillance colonoscopy was 29 months (25th–75th percentile 16–54 months).

C. Time of third surveillance colonoscopy after second normal colonoscopy for 11,666 patients. This graph includes both diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopies. This graph includes both diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopy. The median time between second and third surveillance colonoscopy was 33 months (25th–75th percentile 18–57 months).

The timing of any follow-up colonoscopies changed somewhat over the 1992–2002 study period. Table 3 presents the median and 25th and 75th percentiles for months between first normal colonoscopy and the second colonoscopy for any reason, and also between a second normal colonoscopy and any third colonoscopy. Between cancers initially treated in 1992–94 and 2001–03, there was a significant trend for somewhat longer median times between the first normal colonoscopy and any follow up colonoscopy, from 26 months in 1992–94 to 32 months in 2001–03. There was no clear temporal pattern of change over time in the interval between the second and third colonoscopy.

Table 3.

Change overtime in the intervals between the first and second and third colonoscopy during the study period.*

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | 1992–1994 | 1995–1997 | 1998–2000 | 2001–2003 | Log rank P-value*** |

|

| Time between first and second colonoscopy (months) | Q1 | 14* | 15 (15 – 16) | 17 (16 – 18) | 19 (18 – 20) | <0.0001 |

| Q2 | 26 (25 – 27) | 28 (27 – 30) | 31 (29 – 32) | 32 (30 – 34) | ||

| Q3 | 58 (51 – 66) | 52 (48 – 57) | 53 (50 – 60) | |||

| Time between second and third colonoscopy (months) | Q1 | 15 (14 – 15) | 18 (17 – 20) | 23 (21 – 24) | 22 (19 – 23) | 0.0106 |

| Q2 | 31 (28 – 33) | 36 (34 – 37) | 36 (35 – 37) | 29 (28 – 32) | ||

| Q3 | 60 (55 – 63) | 60 (56 – 64) | 56 (50 – 61) | |||

The median and 25th and 75th percentiles for months between a first normal colonoscopy following surgery for colorectal cancer and any follow up colonoscopy are given.

Requiring weekly data to estimate 95% confidence interval, the rate of colonoscopy jumped from 21.9% at 13 months to 28.8% at 14 months.

The log rank test assesses the rate of colonoscopy at the entire follow-up period between patients diagnosed at different eras.

To further investigate the potential use of colonoscopy earlier than recommended, we identified patients who received a second colonoscopy within two years of a normal first colonoscopy and those who received a third colonoscopy within two years of a normal second colonoscopy. Among these, we identified patients with a claim that suggested a diagnostic purpose for the colonoscopy. The remaining patients were considered to have undergone surveillance colonoscopy after a normal prior colonoscopy. Table 4 presents the percentage of patients who had early surveillance colonoscopy, stratified by patient, geographic and tumor characteristics. Overall, 32.1% of patients with a normal first colonoscopy underwent a second colonoscopy within two years for surveillance. Similarly, 27.3% of patients with second normal colonoscopy underwent a third colonoscopy within two years for surveillance. This occurred more often in younger patients, but was still at ≥ 20% for patients aged 80 or older. There were also marked variations among the SEER areas, with Seattle having rates approximately one third of those of New Mexico. Patients with previous colonoscopy by a surgeon or by a more recently trained physician were more likely to undergo a subsequent early surveillance colonoscopy.

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients who underwent a second or third surveillance colonoscopy within two years of a previous normal colonoscopy. ****

| Patients with normal first colonoscopy | Patients normal second colonoscopy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Category | N | Received 2nd surveillance colonoscopy* within 2 years after 1st normal colonoscopy |

p-value | N | Received 3rd Surveillance colonoscopy* within 2 years after 2nd normal colonoscopy |

p-value |

| Overall | 14144**** | 32.1 | 8047**** | 27.3 | |||

| Age (years) | 67 – 69 | 1755 | 45.0 | <0.0001 | 546 | 46.3 | <0.0001 |

| 70 – 74 | 3775 | 36.2 | 2314 | 30.9 | |||

| 75 – 79 | 4045 | 32.3 | 2515 | 27.7 | |||

| ≥ 80 | 4569 | 23.6 | 2672 | 20.0 | |||

| Gender | Male | 5957 | 34.2 | <0.0001 | 3457 | 28.7 | 0.0146 |

| Female | 8187 | 30.6 | 4590 | 26.3 | |||

| Ethnicity | White | 12352 | 32.1 | 0.3008 | 7046 | 27.2 | 0.3411 |

| Black | 819 | 33.9 | 418 | 29.0 | |||

| Hispanic | 435 | 32.2 | 252 | 31.0 | |||

| Other | 538 | 29.0 | 331 | 24.8 | |||

| SEER Regions | Connecticut | 1383 | 31.0 | <0.0001 | 821 | 21.7 | <0.0001 |

| Detroit | 1801 | 42.3 | 1254 | 35.9 | |||

| Hawaii | 214 | 26.2 | 131 | 19.9 | |||

| Iowa | 2408 | 35.1 | 1567 | 28.8 | |||

| New Mexico | 343 | 46.7 | 241 | 38.2 | |||

| Seattle | 938 | 16.4 | 532 | 13.5 | |||

| Utah | 425 | 33.7 | 238 | 28.2 | |||

| Atlanta/Rural Georgia | 608 | 28.1 | 347 | 22.2 | |||

| Kentucky | 784 | 25.3 | 307 | 27.0 | |||

| Louisiana | 619 | 30.4 | 242 | 28.9 | |||

| New Jersey | 1301 | 39.1 | 584 | 34.9 | |||

| California | 3320 | 28.0 | 1783 | 24.0 | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 8090 | 34.1 | <0.0001 | 4856 | 28.5 | 0.0026 |

| Not Married | 6054 | 29.5 | 3191 | 25.5 | |||

| Census Track education (% adult less than 12 years education) |

< 9.1% | 3398 | 30.1 | 0.0012 | 1932 | 25.5 | 0.0023 |

| 9.1 – < 15.3% | 3436 | 31.1 | 1984 | 25.4 | |||

| 15.3 – < 23.4% | 3514 | 34.4 | 2029 | 28.3 | |||

| ≥ 23.4% | 3625 | 32.9 | 1978 | 30.2 | |||

| Census Track below poverty |

< 4.1% | 3178 | 35.2 | 0.0001 | 1931 | 28.5 | 0.6407 |

| 4.1 – < 7.7% | 3417 | 32.3 | 1962 | 26.8 | |||

| 7.7 – < 15.1% | 3578 | 30.0 | 2057 | 26.5 | |||

| ≥ 15.1% | 3800 | 31.6 | 1973 | 27.6 | |||

| Comorbidity | 0 | 10810 | 28.9 | <0.0001 | 5617 | 27.3 | 0.0919 |

| 1 | 2092 | 43.3 | 1621 | 28.9 | |||

| 2 | 743 | 43.5 | 506 | 25.5 | |||

| ≥3 | 499 | 37.3 | 303 | 22.4 | |||

| Year of diagnosis |

1992 | 988 | 37.7 | <0.0001 | 719 | 32.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1993 | 870 | 39.3 | 646 | 30.0 | |||

| 1994 | 876 | 35.8 | 642 | 30.5 | |||

| 1995 | 853 | 39.0 | 629 | 25.9 | |||

| 1996 | 839 | 33.6 | 689 | 27.1 | |||

| 1997 | 880 | 30.1 | 681 | 23.9 | |||

| 1998 | 940 | 33.1 | 706 | 23.4 | |||

| 1999 | 887 | 27.5 | 578 | 20.4 | |||

| 2000 | 1913 | 29.3 | 1251 | 23.8 | |||

| 2001 | 1860 | 30.1 | 925 | 27.8 | |||

| 2002 | 1781 | 28.4 | 581 | 39.1 | |||

| 2003 | 1457 | 31.2 | |||||

| AJCC stage | 1 | 4762 | 30.4 | 0.0004 | 2838 | 27.0 | 0.0297 |

| 2 | 5587 | 31.9 | 3147 | 26.3 | |||

| 3 | 3741 | 34.5 | 2035 | 29.5 | |||

| Grade | Well | 1361 | 31.5 | 0.7045 | 765 | 25.1 | 0.1824 |

| Moderate | 9735 | 32.0 | 5528 | 27.9 | |||

| Poor/Unknown | 2283 | 32.8 | 1284 | 26.3 | |||

| Physician specialty** |

Gastroenterology | 6542 | 29.8 | <0.0001 | 3748 | 25.5 | 0.0041 |

| Generalist | 987 | 32.9 | 594 | 26.1 | |||

| Surgeon | 5703 | 34.7 | 3134 | 29.3 | |||

| Other | 317 | 31.3 | 187 | 27.3 | |||

| Years since graduation of the colonoscopist *** |

< 10 | 536 | 41.8 | <0.0001 | 369 | 30.4 | 0.5395 |

| 10 – 19 | 3921 | 34.0 | 2450 | 26.9 | |||

| 20 – 29 | 4658 | 30.6 | 2625 | 26.8 | |||

| >=30 | 2731 | 30.4 | 1346 | 27.1 | |||

Surveillance colonoscopy is defined as a colonoscopy with no diagnosis or prior procedure suggesting it was done for diagnostic reasons. Among all the patients who underwent a colonoscopy within 2 years after the first and second any colonoscopy diagnostic indication was found in 21% and 23% patients, respectively.

Data on physician specialty was missing for 595 patients (4.2%) and 384 patients (4.8%) for 1st and 2nd colonoscopy, respectively.

Data on year of graduation was missing for 2298 patients (16.3%) and 1257 patients (15.6%) for 1st and 2nd colonoscopy, respectively. Specialty and experience were all characteristics of the previous colonoscopy; for example in the analysis of early second surveillance colonoscopy, these are the characteristics related to first colonoscopy.

These analyses are limited to patients with a normal colonoscopy, with at least two years of follow-up data after that colonoscopy, to assess receipt of early subsequent surveillance colonoscopy. Surveillance colonoscopy is a colonoscopy lacking a diagnosis indicating it might be done to evaluate a specific symptom.

Table 5 presents the results of multivariable analyses of odds of receiving an early surveillance colonoscopy. Most of the associations found in the bivariate analyses in Table 4 are maintained. There is a clear decline in older patients, with no association with gender, ethnicity, marital status or education. There was a temporal decrease in odds of receiving early surveillance between the early 1990’s and the 2000’s. Tumor stage and grade had a modest or no effect on odds of receiving early surveillance colonoscopy. Surgeons and more recently trained physicians were more likely to be associated with early surveillance colonoscopy.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis of patient characteristics associated with odds of receiving an early second or third surveillance colonoscopy within two years after a normal colonoscopy.

| Second Surveillance Colonoscopy within 2 years after the 1st normal colonoscopy* |

Third Surveillance Colonoscopy within 2 years after the normal 2nd colonoscopy* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Category | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Age | 67 – 69 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 70 – 74 | 0.80 | (0.73, 0.87) | 0.69 | (0.60, 0.80) | |

| 75 – 79 | 0.73 | (0.67, 0.80) | 0.63 | (0.55, 0.73) | |

| ≥ 80 | 0.55 | (0.50, 0.60) | 0.47 | (0.40, 0.54) | |

| Gender | Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.97 | (0.91, 1.03) | 0.96 | (0.88, 1.05) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 0.95 | (0.84, 1.09) | 0.96 | (0.79, 1.17) | |

| Hispanic | 0.93 | (0.78, 1.11) | 0.98 | (0.77, 1.25) | |

| Other | 1.02 | (0.85, 1.23) | 1.08 | (0.84, 1.40) | |

| SEER Regions | Connecticut | 1.92 | (1.59, 2.31) | 1.62 | (1.23, 2.14) |

| Detroit | 2.45 | (2.05, 2.92) | 2.55 | (1.99, 3.28) | |

| Hawaii | 1.61 | (1.15, 2.25) | 1.29 | (0.79, 2.10) | |

| Iowa | 2.09 | (1.76, 2.49) | 2.15 | (1.67, 2.76) | |

| New Mexico | 2.83 | (2.26, 3.55) | 2.73 | (1.99, 3.75) | |

| Seattle | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Utah | 2.02 | (1.61, 2.53) | 1.99 | (1.43, 2.79) | |

| Atlanta/Rural Georgia | 1.70 | (1.36, 2.12) | 1.58 | (1.15, 2.19) | |

| Kentucky | 1.69 | (1.35, 2.11) | 1.93 | (1.38, 2.71) | |

| Louisiana | 2.02 | (1.61, 2.52) | 1.97 | (1.39, 2.79) | |

| New Jersey | 2.79 | (2.31, 3.36) | 2.52 | (1.89, 3.35) | |

| California | 1.84 | (1.55, 2.19) | 1.78 | (1.38, 2.29) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 1.06 | (0.99, 1.13) | 1.03 | (0.94, 1.13) |

| Not Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Census Track education (% adult < 12 years education) |

< 9.1% | ||||

| 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 9.1 – < 15.3% | 0.99 | (0.91, 1.09) | 0.98 | (0.86, 1.11) | |

| 15.3 – < 23.4% | 1.03 | (0.94, 1.12) | 1.03 | (0.91, 1.17) | |

| ≥ 23.4% | 1.00 | (0.91, 1.09) | 1.08 | (0.95,1.24) | |

| Comorbidity | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.46 | (1.35, 1.57) | 1.09 | (0.98, 1.21) | |

| 2 | 1.49 | (1.32, 1.67) | 0.96 | (0.80, 1.15) | |

| ≥3 | 1.29 | (1.11, 1.50) | 0.85 | (0.66, 1.08) | |

| Year of diagnosis |

1992 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1993 | 1.03 | (0.89, 1.19) | 0.94 | (0.77, 1.13) | |

| 1994 | 0.95 | (0.82, 1.11) | 0.98 | (0.81, 1.18) | |

| 1995 | 1.04 | (0.90, 1.21) | 0.82 | (0.67, 1.00) | |

| 1996 | 0.91 | (0.78, 1.06) | 0.89 | (0.74, 1.09) | |

| 1997 | 0.81 | (0.69, 0.95) | 0.78 | (0.64, 0.96) | |

| 1998 | 0.89 | (0.76, 1.04) | 0.77 | (0.63, 0.94) | |

| 1999 | 0.76 | (0.64, 0.89) | 0.68 | (0.55, 0.85) | |

| 2000 | 0.77 | (0.67, 0.88) | 0.74 | (0.62, 0.89) | |

| 2001 | 0.77 | (0.67, 0.88) | 0.82 | (0.68, 1.00) | |

| 2002 | 0.73 | (0.63, 0.84) | 1.15 | (0.95, 1.41) | |

| 2003 | 0.80 | (0.69, 0.92) | |||

| AJCC stage | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 1.05 | (0.98, 1.13) | 0.96 | (0.87, 1.06) | |

| 3 | 1.10 | (1.02, 1.19) | 1.06 | (0.95, 1.18) | |

| Grade | Well | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Moderate | 1.03 | (0.93, 1.14) | 1.14 | (0.98, 1.33) | |

| Poor/Unknown | 1.07 | (0.94, 1.20) | 1.09 | (0.91, 1.31) | |

| Physician Specialty |

Gastroenterology | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Generalist | 1.06 | (0.94, 1.20) | 1.00 | (0.84,1.19) | |

| Surgeon | 1.14 | (1.07, 1.22) | 1.10 | (0.99, 1.21) | |

| Other | 0.96 | (0.79, 1.17) | 0.90 | (0.67, 1.19) | |

| Years since graduation of the colonoscopist |

< 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | (0.75, 1.13) | |

| 10 – 19 | 0.83 | (0.72, 0.96) | 0.92 | (0.75, 1.13) | |

| 20 – 29 | 0.77 | (0.67, 0.89) | 0.94 | (0.77, 1.15) | |

| >=30 | 0.77 | (0.67, 0.90) | 0.94 | (0.76, 1.16) | |

Surveillance colonoscopy is defined as a colonoscopy with no diagnosis or prior procedure suggesting it was done for diagnostic reasons.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that some patients with colorectal cancer who have undergone curative resection undergo surveillance colonoscopy more frequently than recommended by the guidelines, while other patients never receive any surveillance colonoscopy. We sought to estimate the magnitude and predictors of overutilization of surveillance colonoscopy.

We found that 32% and 27% of patients underwent early second and third surveillance colonoscopy for no clear indication, respectively. This is a conservative estimate, as we defined colonoscopy performed within two years as early surveillance colonoscopy. The current recommendation by most gastroenterology and oncology societies is to perform a second surveillance at three years and a third surveillance colonoscopy at five years.11, 13 Further, we included only patients whose prior colonoscopy was not associated with any additional procedure like biopsy or polyp removal. The histologic findings in some of these patients undergoing additional procedures would have been non-adenomatous (e.g., hyperplastic polyps, normal colon mucosa) requiring no need to shorten the surveillance interval. Of interest, potential clinical indications for more frequent surveillance, such as tumor stage or histological grade, had no or minimal association with receipt of early surveillance.

The underlying reasons for this pattern of overutilization are probably related to physician practice patterns and patient demands. There is significant variability in physician recommendations as well as physician adherence to the guidelines for surveillance colonoscopy intervals and follow up in colorectal cancer survivors.25–27 A survey of colorectal surgeons in the United States on the follow up and surveillance of colorectal cancer survivors revealed that only 49% adhered to guidelines. In that study, the surveillance intervals recommended by the surgeons varied from annually (14% of physicians) to once in five years (10% of physicians).26 Similar variability exists among the primary care providers (PCP) and oncologists, who generally comprise the first point of contact for follow up of colorectal cancer patients.25,27 The awareness of and adherence to the guidelines among PCPs and oncologists plays a very important role in the utilization pattern of surveillance colonoscopy. Often, the endoscopist does not see the patient in the clinic prior to performing the colonoscopy. These patients are referred directly for the procedure by either their PCP or oncologist.

Another potential explanation for performance of surveillance colonoscopy at intervals shorter than recommended is imbedded in patient behavior and demands. Colorectal cancer survivor patients may be anxious about tumor recurrence and may request that procedures be performed more frequently than recommended by guidelines.28–30

We observed significant regional variation in the use of early second and third surveillance colonoscopy. Patients in some SEER regions were more than twice as likely to undergo early surveillance colonoscopy than those in other regions. Areas with higher rates of early second surveillance colonoscopy consistently had similarly higher rates of early third surveillance colonoscopy. The regional variation is likely related to variation in practice patterns and health care delivery systems.16, 31, 32

It is troubling that a significant percentage of patients older than 80 years underwent early surveillance colonoscopy. There are no clear recommendations on the age limit for performance of surveillance colonoscopy after curative colorectal cancer resection. Guidelines from American Cancer Society and US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommend discontinuing surveillance colonoscopy in patients with a life expectancy less than 10 years.11 In this study, we also found that patients with multiple comorbidities had a higher likelihood of receiving an early surveillance colonoscopy with no clear indication. It is unclear why these patients undergo surveillance colonoscopy more often. It may be that patients with multiple comorbidities see multiple medical providers, increasing their risk of being recommended for another surveillance colonoscopy.

There was a significant decrease in occurrence of early surveillance colonoscopy during the study period (1992–2003). This was noted for the second surveillance colonoscopy. We analyzed the trend of colonoscopy utilization over the study period and found a significantly increasing interval (Table 3). This decrease in occurrence of early surveillance colonoscopy may be related to increased awareness among physicians about post cancer surveillance guidelines. In 1997, Winawer et al. published guidelines endorsed by major gastroenterology, surgery and oncology societies.12 In these guidelines, the authors stated there is no evidence to suggest that the rate of progression of adenomatous polyps to cancer was different among patients who have had cancer from those in average-risk individuals.

In our study we also found under-utilization of surveillance colonoscopy (Figure 1). Cooper et al. and others have tried to address the predictors of under-utilization of surveillance colonoscopy.15–19 Decreased rates of surveillance colonoscopy were associated with advanced age, African American race and with multiple co-morbidities. It is also likely that the overuse of limited resources may play a role in many patients not receiving the surveillance colonoscopy at the recommended intervals.

Our study had several limitations. Some procedures could be performed sooner than recommended by the guidelines due to suboptimal bowel preparation of the prior examination. Details of the colonoscopy, such as the quality of bowel preparation and the actual procedure findings, were not known from the administrative data. However, to minimize the effect of bowel preparation, we did not include any repeat procedures performed within three months of the surgery or prior colonoscopy. The estimates obtained in this study are for are for the population greater than 66 years, and cannot be extrapolated to younger populations.

Our study shows that many patients who underwent curative resection for colorectal cancer receive surveillance colonoscopy sooner than recommended by the guidelines. This study provides an estimate of the magnitude of the overuse and is the first step in evaluating this problem. Future studies are required to further assess the influence of physician practice parameters as well as patient behaviors, which lead to more frequent performance of surveillance colonoscopy than recommended by the guidelines.

Acknowledgements

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

This work was supported in part by the Comparative Effectiveness Research on Cancer in Texas (CERCIT) Grant #RP101207, funded by The Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) and the National Institutes of Health (1R01 CA134275 and 1K05 CA134923).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Amanpal Singh: (study concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript)

Yong-Fang Kuo: (statistical analysis, critical revision of the manuscript)

James S. Goodwin: (study concept and design, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript, administrative, technical or material support; study supervision)

Financial Disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist

References

- 1.Society AC. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor WE, Donohue JH, Gunderson LL, et al. The Mayo Clinic experience with multimodality treatment of locally advanced or recurrent colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(2):177–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02557371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rectum SSFSCa. [accessed March 29, 2012]; http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html.

- 4.Jacob BP, Salky B. Laparoscopic colectomy for colon adenocarcinoma: an 11-year retrospective review with 5-year survival rates. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(5):643–649. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson RM, Perencevich NP, Malcolm AW, Chaffey JT, Wilson RE. Patterns of recurrence following curative resection of adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1980;45(12):2969–2974. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800615)45:12<2969::aid-cncr2820451214>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckardt VF, Stamm H, Kanzler G, Bernhard G. Improved survival after colorectal cancer in patients complying with a postoperative endoscopic surveillance program. Endoscopy. 1994;26(6):523–527. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Follow-up after curative resection of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1783–1799. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang T, Cui Y, Huang WS, et al. The role of postoperative colonoscopic surveillance after radical surgery for colorectal cancer: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3 Pt 2):609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castells A, Bessa X, Daniels M, et al. Value of postoperative surveillance after radical surgery for colorectal cancer: results of a cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(6):714–723. doi: 10.1007/BF02236257. discussion 23-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lautenbach E, Forde KA, Neugut AI. Benefits of colonoscopic surveillance after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220(2):206–211. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199408000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rex DK, Kahi CJ, Levin B, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after cancer resection: a consensus update by the American Cancer Society and the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(6):1865–1871. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(2):594–642. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson AB, Desch CE, Flynn PJ, et al. 2000 update of American Society of Clinical Oncology colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(20):3586–3588. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony T, Simmang C, Hyman N, et al. Practice parameters for the surveillance and follow-up of patients with colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(6):807–817. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0519-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Reynolds HL. Receipt of guideline-recommended follow-up in older colorectal cancer survivors : a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2029–2037. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salz T, Weinberger M, Ayanian JZ, et al. Variation in use of surveillance colonoscopy among colorectal cancer survivors in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:256. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu CY, Delclos GL, Chan W, Du XL. Post-treatment surveillance in a large cohort of patients with colon cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(5):329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper GS, Payes JD. Temporal trends in colorectal procedure use after colorectal cancer resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(6):933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elston Lafata J, Simpkins J, Schultz L, et al. Routine surveillance care after cancer treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2005;43(6):592–599. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163656.62562.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora G, Mannalithara A, Singh G, Gerson L, Triadafilopoulos G. Risk of perforation from a colonoscopy in adults: a large population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3 Pt 2):654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin T, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):880–886. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren J, Klabunde C, Mariotto A, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(12):849–857. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00008. W152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeff L, Manninen D, Dong F, et al. Is there endoscopic capacity to provide colorectal cancer screening to the unscreened population in the United States? Gastroenterology. 2004;127(6):1661–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown M, Klabunde C, Mysliwiec P. Current capacity for endoscopic colorectal cancer screening in the United States: data from the National Cancer Institute Survey of Colorectal Cancer Screening Practices. Am J Med. 2003;115(2):129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians' and oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano P, Efron J, Vernava AM, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Strategies of follow-up for colorectal cancer: a survey of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10(3):199–207. doi: 10.1007/s10151-006-0280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nissen MJ, Beran MS, Lee MW, Mehta SR, Pine DA, Swenson KK. Views of primary care providers on follow-up care of cancer patients. Fam Med. 2007;39(7):477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papagrigoriadis S, Heyman B. Patients' views on follow up of colorectal cancer: implications for risk communication and decision making. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(933):403–407. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.933.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stiggelbout AM, de Haes JC, Vree R, et al. Follow-up of colorectal cancer patients: quality of life and attitudes towards follow-up. Br J Cancer. 1997;75(6):914–920. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489–2495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson FE, McKirgan LW, Coplin MA, et al. Geographic variation in patient surveillance after colon cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):183–187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neils DM, Virgo KS, Longo WE, et al. Geographic variation in follow-up after rectal cancer surgery. Int J Oncol. 2007;30(3):735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]