Abstract

Background

Although smoking rates in the United States (US) are high, healthcare systems and clinicians can increase cessation rates through application of the US Public Health Service tobacco treatment guideline (2000, 2008). In primary care settings, however, guideline implementation remains low. This report presents the results from an assessment of patient tobacco use, quit attempts, and perceptions of provider treatment before (2004) and after (2010) guideline implementation.

Methods

By use of a systems approach, the Louisiana Tobacco Control Initiative integrated evidence-based treatment of tobacco use into patient care practices in Louisiana's public hospital system. This prospective study, designed to collect data at 2 time points for the purpose of evaluating the effect of the 5A protocol (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange), included 571 and 889 adult patients selected from primary care clinics in 2004 and 2010, respectively. Chi-square analyses determined differences between survey administrations, along with direct standardization of weighted rates to control for confounding factors.

Results

Patient reports indicated that provider adherence to the 5A clinical protocol increased from 2004 to 2010. Significant (P<0.001) improvements were observed for the assess (39% vs 72%), assist (24% vs 76%), and arrange (8% vs 31%) treatment variables. Patient-reported quit attempts increased, along with awareness of cessation services (from 19% to 70%, P<0.001), while use of cessation medications decreased (from 23% to 5%, P<0.002).

Conclusion

Following implementation of the guideline, significant improvements were noted in patient reports of provider treatment and awareness of cessation services.

Keywords: Guideline adherence, physician's practice patterns, smoking cessation

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use continues to lead the nation as a preventable cause of morbidity and mortality.1 Despite reductions over the past 3 decades in smoking among the nation's general population,2 rates of tobacco use remain high among low-income, less-educated, minority, and under- and uninsured groups.3 Louisiana's smoking prevalence (22%) is higher than the national average (17%).4 Nationwide, smoking rates vary by insurance coverage: 16% of those covered by private insurance smoke, compared to 30% of public insurance enrollees (Medicaid and Medicare) and 32% of uninsured residents.5 In Louisiana, a large proportion (25%) of residents is uninsured; 34% of these smoke.6

Healthcare providers and delivery systems can impact population-level cessation rates through implementation of the US Public Health Service (USPHS) clinical practice guideline (CPG) Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update that includes the 5A protocol: (1) ask about tobacco use, (2) advise all identified smokers to quit, (3) assess smokers' willingness to quit, (4) assist smokers in their quit attempt, and (5) arrange for follow-up contact. Furthermore, the CPG delineates standards for quality care, endorses the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments for tobacco use, and provides strategies for integrating screening and treatment into routine patterns of care. Nearly 70% of smokers visit a physician at least once a year, providing an opportunity for intervention.7 However, CPG implementation in primary care settings is less than optimal.8

Patients' perceptions of their care have become increasingly important to health systems as many seek to improve the quality and satisfaction with treatments and to provide patient-centered care.9,10 When tobacco users receive treatment according to the CPG, they report higher satisfaction with overall healthcare received relative to untreated tobacco users.7 Provider treatment of tobacco use can be measured by patient surveys (eg, Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, National Health Interview Survey), provider surveys, medical record reviews, and direct observation. However, limitations exist for each of these and results vary. While direct observation is the standard for assessing provider treatment, healthcare systems can benefit from precise, cost-effective, and practical approaches to obtaining patient perceptions of provider intervention.11,12 Patient surveys are more accurate than chart audits for assessing chronic disease advice, information dissemination, and, in some instances, general health promotion.13

In 2002, to accompany an increase in the excise tax on cigarettes, the Louisiana State University School of Public Health (LSUSPH), in partnership with Louisiana's safety-net healthcare system, created the Tobacco Control Initiative (TCI). The TCI, described in detail elsewhere,14 employed a systems approach to facilitate implementation of the CPG in the LSU network of public hospitals. This report presents results from an assessment of patient tobacco use, quit attempts, and perceptions of provider treatment before (2004) and after (2010) the CPG implementation in Louisiana's safety-net healthcare system.

METHODS

Sampling

In May 2004, patients ≥18 years old and using LSU as their principal source of primary care were evaluated. Eligible participants met the condition of 1 or more visits to an LSU primary care clinic in the prior year. A follow-up survey was conducted in January 2010. Participants were eligible in 2010 if they had had 1 or more visits to an LSU primary care clinic during survey administration.

A stratified, 2-stage, cluster sampling plan was used in 2004 and 2010. In 2004, the first stage included 10 public hospitals in the system and 44 nonpediatric primary care clinics. For each clinic, the survey was conducted during approximately 70 operating days during the quarter; for each stratum, 2 of these operating days (a total of 44 × 2 = 88) were selected as the first-stage cluster sample. The second stage in 2004 involved choosing specific participants within each clinic-day combination. After further stratifying by age and gender, subjects were selected randomly from appointments scheduled for the clinic on the selected days.

In 2010, the first-stage cluster sampling plan included 7 public hospitals in the system and 29 nonpediatric clinics. For each clinic, a survey time was assigned over a 2-week period. Each day, the surveyors were required to visit 1 clinic for about 2 hours, either in the morning or the afternoon, thus designating a total of 10 slots for the 2-week period (10 weekdays). The second stage in 2010 included participants within each clinic-day combination. In this survey, all subjects presenting to the clinic during the assigned time slot were included. Because clinic patient loads varied, the samples collected for each stratum were determined in proportion to the relative patient volume of each clinic.

Survey Instrument

Both surveys contained items found in other national surveys (eg, National Health Interview Survey, Adult Tobacco Survey, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System). The 2004 survey consisted of 8 sections: Health Status, Health Care Access, Demographics, Tobacco Use, Quit Attempts and Methods to Quit, Stages of Change for Quitting, Physician and Health Professional Behavior, and Other Tobacco Use. The 2010 survey consisted of 3 sections: Tobacco Use, Quit Attempts and Methods to Quit, and Physician and Health Professional Behavior.

Survey Administration

In 2004, surveys were administered by interviewers and conducted in a private area in the clinic prior to the patients' interaction with the healthcare provider. After agreeing to take the survey, patients completed consent procedures and were informed they would be compensated $10 for their time. The response rate was 95%. Participants' responses were recorded on a hard copy of the survey instrument. Payment was mailed after the interview.

In 2010, considerations of cost and sustainability resulted in changes to the survey methodology. Self-administered surveys were distributed to all patients presenting for a clinic visit with the request to complete them prior to their clinic visit. A TCI tobacco cessation coordinator provided clinic intake clerks with surveys, clipboards, and pencils that were given to all patients at appointment check-in. This approach yielded a 99% response rate. Because survey participation was both voluntary and anonymous, and the survey was made available to all patients, it was not necessary for patients to complete an informed consent or patient privacy form. Participants did not receive compensation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the LSU Health Sciences Center and by the Research Review Committee of each facility.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the demographic characteristics of respondents were derived. For the purpose of comparing 2004 and 2010 patients, the results were standardized by the gender and age population distribution in 2010. All analyses were weighted to account for the complex sampling design. Chi-square analyses were conducted to explore 2004 and 2010 differences among patients who were smokers. Weighting of analytical procedures was accomplished with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To allow valid comparison of groups, direct standardization (or adjustment) of rates was used to minimize the influence of confounding factors.

RESULTS

Changes in Demographic Status

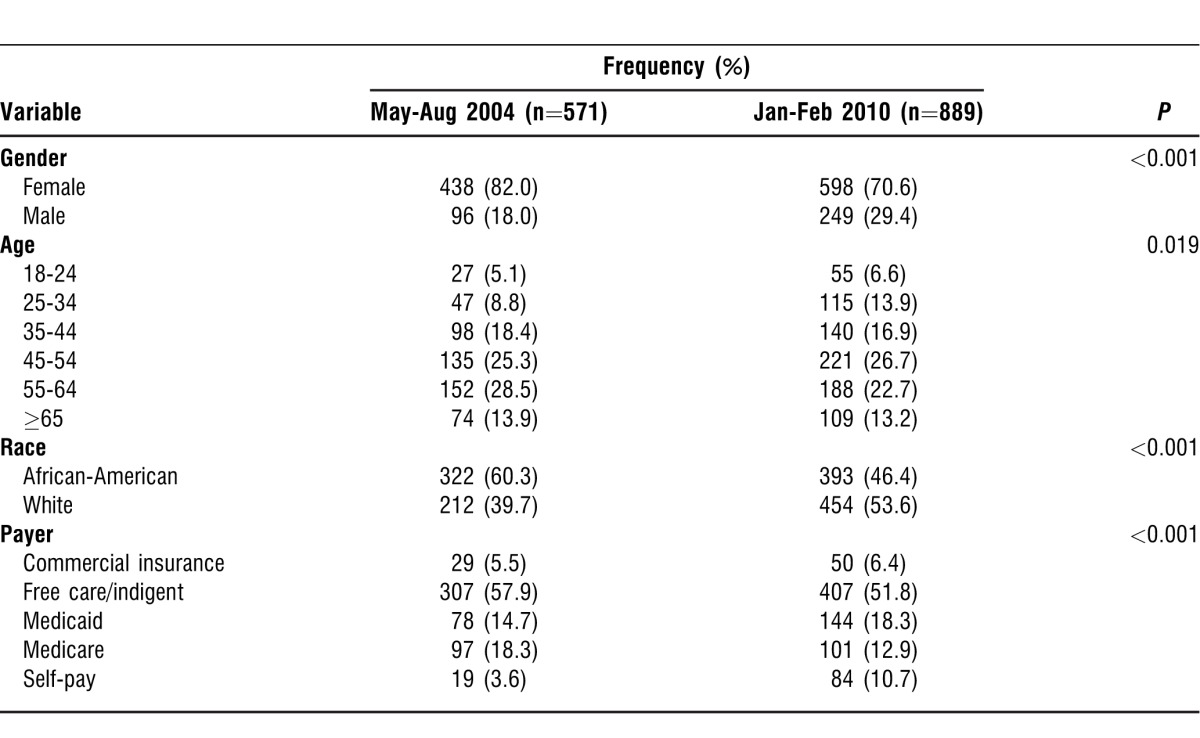

Included in the results were 571 patients in 2004 and 889 patients in 2010, representing the 7 hospitals in the Louisiana public hospital system that participated in both administrations of the survey. Table 1 shows the demographics for the samples. About two-thirds of the patients were ≥45 years old. The sample was predominantly female (82% in 2004 vs 71% in 2010). In 2004, most of the patients were African-American (60%). In 2010, however, more than half the patients were white (54%). Most patients were lower income, with 58% of the participants reporting free care (indigent) status in 2004 and 52% in 2010.

Table 1.

Demographic Status

Changes in Tobacco Use

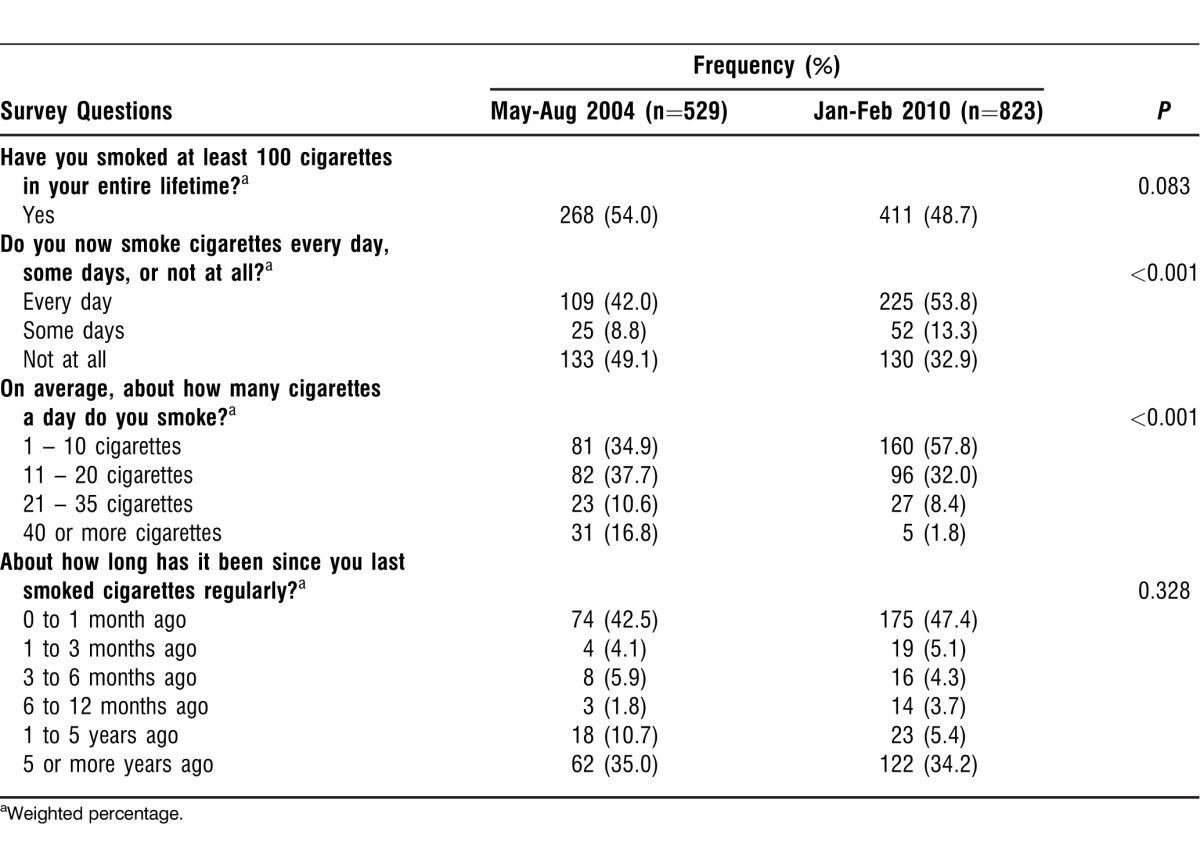

To compare patients in 2004 and 2010, the results were standardized by gender and age distribution using the 2010 population distribution. Chi-square analyses were conducted to explore 2004 and 2010 differences among patients who were smokers. Table 2 shows the tobacco use status in 2004 and 2010. In general, the proportion of ever smokers was similar (54% vs 49%; P=0.083). Between 2004 and 2010, no significant differences were found for the period of time since ever smokers had last smoked cigarettes (P=0.328). However, the percentage of heavy smokers (those who smoke more than 11 cigarettes per day) was higher in 2004 than in 2010 (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Tobacco Use in Patients Who Have Smoked at Least 100 Cigarettes in Their Lifetimes

Changes in Patient Perceptions of Physician and Health Professional Behaviors

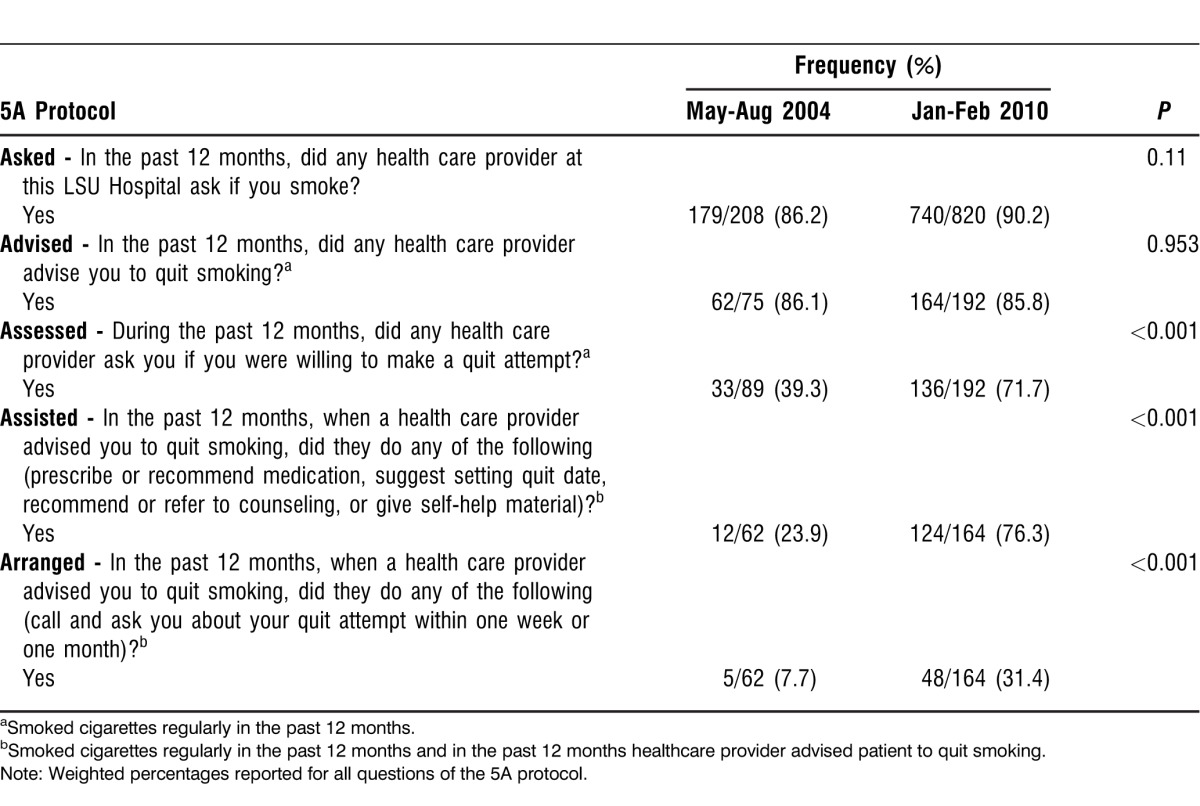

To determine if, in their interactions with smokers, healthcare providers were following the CPG related to smoking cessation, smokers were questioned about interactions with healthcare providers. Specifically, smokers were asked about their tobacco use and whether the healthcare provider gave advice to quit smoking. Table 3 shows the patient-reported healthcare provider behaviors regarding the CPG 5A protocol: ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange. In 2004 and 2010, 86%-90% of patients reported that their healthcare provider had asked and advised them to quit smoking in the past 12 months. In 2010, however, healthcare providers did a better job in assessing, assisting, and arranging. Table 3 shows that 72% of patients had been assessed during the past 12 months in 2010, but only 39% of patients were assessed during the previous 12 months in 2004 (P<0.001). Similarly, 76% of patients had been assisted in the past 12 months in 2010, but only 24% of patients had been assisted in the previous 12 months in 2004 (P<0.001). In addition, 31% of patients had cessation services arranged in 2010, but only 8% of patients had services arranged in 2004 (P<0.001).

Table 3.

Physician and Health Professional Behaviors

Changes in Patient-Reported Quit Attempts and Methods

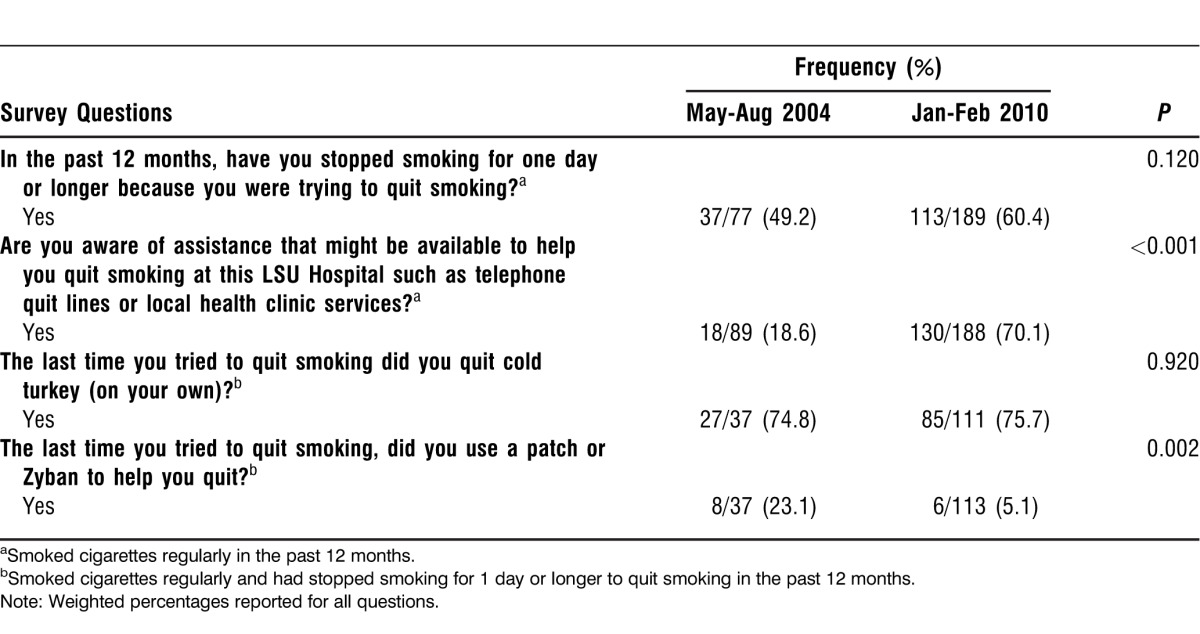

Table 4 shows the quit-smoking behaviors reported by patients who smoked. Although the proportion of smokers who stopped smoking for 1 day or longer was higher in 2010 (60%) vs 2004 (49%), the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.120). In 2010, a significantly higher proportion of smokers reported being aware of assistance (70%) such as telephone quit lines or cessation services at local LSU hospitals; however, only 19% of smokers were aware of such assistance in 2004 (P<0.001). Nearly the same percentage of those who smoked cigarettes regularly and had stopped smoking for 1 day or longer to quit smoking in the past 12 months (75% in 2004 and 76% in 2010, P=0.920) reported that they tried to quit smoking on their own (cold turkey). A significant difference was found in the use of an aid to quit smoking. More smokers in 2004 than in 2010 stated they used a stop-smoking product such as a nicotine patch or bupropion hydrochloride (Zyban) (23% in 2004 vs 5% in 2010, P=0.002).

Table 4.

Quit Attempts and Methods

DISCUSSION

The survey findings suggest that integrating the USPHS CPG in a large public hospital system impacts patient tobacco use, quit attempts and methods for quitting, and perceptions of provider treatment behavior. In 2010, fewer respondents reported ever smoking and heavy smoking. While the decrease among ever smokers may be attributed to statewide prevention programs and media campaigns focused on averting smoking initiation, the decrease in those smoking 11 or more cigarettes per day may result from successful quit attempts either on their own or from utilizing cessation services in the LSU Health System. Since 2004, TCI has made free group behavioral counseling, self-help material, access to low-cost pharmacotherapy, and, more recently, access to free quit-line telephone counseling available to aid patient quit attempts. Compared to 2004, more respondents in 2010 reported smoking ≤10 cigarettes per day, daily smoking, and having smoked in the previous month. This trend suggests an emergence of differing levels of smokers and their cessation pathways: smokers who are able to quit and maintain abstinence, smokers who quit and relapse, and recalcitrant smokers.15 Relapsing and recalcitrant smokers are likely recycled in the health system16 and may need tailored services to improve quit attempts and abstinence rates.17 However, the smoking rate of survey participants in both 2004 and 2010 was higher than the rates reported for patients in other primary care settings18,19 and for patients who are uninsured.20

Patient respondents reported an increase in all of the provider treatment measures, except advice to quit, which remained unchanged. There was a slight increase in provider screening for tobacco use and significant increases in providers who assessed patient willingness to quit, assisted patients with their quit attempts, and arranged follow-up for patients after the clinic visit.

These increases may indicate that TCI's effort to galvanize the clinical and patient-level cessation interventions by the LSU Health System were effective, and this systems-based approach may serve as a model for future statewide intervention efforts to decrease patient tobacco use through the systematic implementation and evaluation of the USPHS CPG for treating tobacco use by healthcare providers. Identification and documentation of tobacco users were obtained from nursing assessment forms, followed by TCI referral forms, and finally from electronic medical records with prompts and reminders for intervention. Systemwide adoption of a tobacco treatment policy, training to improve provider intervention skills, and provider feedback on clinical performance via an electronic dashboard occurred throughout the system. These multilevel cessation interventions, including counseling and medication, have been successful in improving adherence to the USPHS CPG for treatment of tobacco use in primary care settings.21 Although few studies have reported patient perceptions of provider adherence to the 5A approach (ask, advise, assess, assist, arrange) in primary care settings, overall our results were more favorable than those found by others in similar settings11,18,22,23 and in studies of the uninsured.8

Respondents reported an increase in quit attempts, and significantly more reported awareness of assistance to help them quit. These increases suggest that TCI's efforts to ensure that all providers were trained to identify and discuss best-practice treatment options with their patients were effective. In addition, TCI employed dedicated tobacco specialists to coordinate cessation services and to support clinicians at each facility. The present results regarding quit attempts were less favorable than results reported in primary care settings19 but higher than in studies among the uninsured.8

Between 2004 and 2010, no change was seen in respondents who reported making a quit attempt on their own (cold turkey), and fewer respondents reported making a quit attempt by using a nicotine patch or Zyban. This finding suggests efforts to increase quit attempts using evidence-based strategies were not equally effective. However, the decrease in use of a patch or Zyban may also be explained by increased access to and availability of varenicline (Chantix) starting in 2006,24 an option that was not on the 2004 survey.

Study limitations should be noted. One limitation is that patient responses were based on their previous clinic visit (ie, surveys were conducted before their current clinic visit). This delayed measurement and reliance on recall may overestimate performance.12 A second limitation is that the results were based on a self-report method. Further, several commonly used methods to assess provider cessation counseling have limitations. Patient surveys may under-23 or overestimate,25,26 provider surveys may overestimate,23,27 paper medical charts may underestimate,25,26,28,29 and electronic medical records may underestimate all items on the 5A protocol, except for asking about tobacco use.11 Direct observation, the ideal method, is burdensome and costly.29 Healthcare systems can benefit from precise, cost-effective, and practical approaches to assessing treatment for tobacco use, and this type of onsite survey distribution proved to be an effective strategy for data collection in Louisiana's public hospital system.

CONCLUSION

This study—which examined patient tobacco use, quit attempts and methods, and perceptions of physician behavior to treat tobacco use among primary care patients in Louisiana's safety-net healthcare system—found positive changes between 2004 and 2010. During this time frame, practice guidelines for the treatment of tobacco use and dependence were implemented. Obviously, these results do not indicate cause and effect because this study was a nonrandomized and noncontrolled observation. Other extraneous factors may have promoted improvements in many of the items measured; however, some differences are quite large and statistically significant. Therefore, these results overall indicate a positive trend in patient behaviors and perceptions of provider care after implementation of the 5A clinical protocol. These observations have implications for eliminating tobacco use at the population level, especially among ethnic/racial minorities, those of low socioeconomic status, and the under- and uninsured. Future studies should examine the effects of implementation experimentally in a randomized-controlled trial and compare patient responses to clinician (electronic) documentation. Furthermore, tailored interventions that target relapsed and recalcitrant smokers and the use of evidence-based strategies during quit attempts are warranted. Decreasing tobacco use is a top objective of Healthy People 2020.30 Improving the quality of treatment through a systems-based approach may impact the disproportionate use of tobacco in especially disparate populations.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Louisiana Cancer Research Consortium.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Systems-Based Practice, and Practice-Based Learning and Improvement.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health;; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrett BE, Dube SR, Trosclair A, Caraballo RS, Pechacek TF. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cigarette smoking - United States, 1965-2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011 Jan 14;60((Suppl)):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness - United States, 2009-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Feb 8;62(5):81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Control State Highlights 2012. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health;; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2009: With Special Feature on Medical Technology. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010:465–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Report. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals;; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service;; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, Shaw L, Engstrom MC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults—National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jun 15;61((Suppl)):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleich SN, Ozaltin E, Murray CK. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ. 2009 Apr;87(4):271–278. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Silverman CB, et al. Measuring provider adherence to tobacco treatment guidelines: a comparison of electronic medical record review, patient survey, and provider survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005 Apr;7((Suppl 1)):S35–S43. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houston TK, Richman JS, Coley HL, et al. DPBRN Collaborative Group. Does delayed measurement affect patient reports of provider performance? Implications for performance measurement of medical assistance with tobacco cessation: a Dental PBRN study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008 May 8;8:100. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green ME, Hogg W, Savage C, et al. Assessing methods for measurement of clinical outcomes and quality of care in primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012 Jul 23;12:214. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moody-Thomas S, Celestin M, Jr, Horswell R. Use of systems change and health information technology to integrate comprehensive tobacco cessation services in a statewide system for delivery of healthcare. Open J Prev Med. 2013;3(1):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wynd CA. Smoking patterns, beliefs, and the practice of healthy behaviors in abstinent, relapsed, and recalcitrant smokers. J Vasc Nurs. 2007 Jun;25(2):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Partin MR, An LC, Nelson DB, et al. Randomized trial of an intervention to facilitate recycling for relapsed smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Oct;31(4):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.021. Epub 2006 Aug 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman SE. A framework for tobacco control: lessons learnt from Veterans Health Administration. BMJ. 2008 May 3;336(7651):1016–1019. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39510.805266.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hahn KA, et al. Self-report versus medical records for assessing cancer-preventive services delivery. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17(11):2987–2994. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralston S, Kellett N, Williams RL, Schmitt C, North CQ. Practice-based assessment of tobacco usage in southwestern primary care patients: a Research Involving Outpatient Settings Network (RIOS Net) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007 Mar-Apr;20(2):174–180. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.02.060018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen KA, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2010 Sep-Oct;51((3-4)):199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.007. Epub 2010 Jun 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahluwalia JS, Gibson CA, Kenney RE, Wallace DD, Resnicow K. Smoking status as a vital sign. J Gen Intern Med. 1999 Jul;14(7):402–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.09078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA. Stafford RS, Singer DE. National patterns in the treatment of smokers by physicians. JAMA. 1998 Feb 25;279(8):604–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.USFDA. FDA Approves Novel Medication for Smoking Cessation: US Food and Drug Administration, May 11, 2006. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm108651.htm Accessed March 14, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pbert L, Adams A, Quirk M, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Luippold RS. The patient exit interview as an assessment of physician-delivered smoking intervention: a validation study. Health Psychol. 1999 Mar;18(2):183–188. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson A, McDonald P. Comparison of patient questionnaire, medical record, and audio tape in assessment of health promotion in general practice consultations. BMJ. 1994 Dec 3;309(6967):1483–1485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6967.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montaño DE, Phillips WR. Cancer screening by primary care physicians: a comparison of rates obtained from physician self-report, patient survey, and chart audit. Am J Public Health. 1995 Jun;85(6):795–800. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson JM, Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, McCarty MC, Vessey J. Patient recall versus physician documentation in report of smoking cessation counselling performed in the inpatient setting. Tob Control. 2000 Dec;9(4):382–388. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Smith TF, et al. How valid are medical records and patient questionnaires for physician profiling and health services research? A comparison with direct observation of patients visits. Med Care. 1998 Jun;36(6):851–867. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.USDHHS. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Tobacco Use Objectives. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=41. Accessed March 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]