Abstract

Background

Residents and fellows perform a large portion of the hands-on patient care in tertiary referral centers. As frontline providers, they are well suited to identify quality and patient safety issues. As payment reform shifts hospitals to a fee-for-value–type system with reimbursement contingent on quality outcomes, preventive health, and patient satisfaction, house staff must be intimately involved in identifying and solving care delivery problems related to quality, outcomes, and patient safety. Many challenges exist in integrating house staff into the quality improvement infrastructure; these challenges may ideally be managed by the development of a house staff quality council (HSQC).

Methods

Residents and fellows at Scott & White Memorial Hospital interested in participating in a quality council submitted an application, curriculum vitae, and letter of support from their program director. Twelve residents and fellows were selected based on their prior quality improvement experience and/or their interest in quality and safety initiatives.

Results

In only 1 year, our HSQC, an Alliance of Independent Academic Medical Centers National Initiative III project, initiated 3 quality projects and began development of a fourth project.

Conclusion

Academic medical centers should consider establishing HSQCs to align institutional quality goals with residency training and medical education.

Keywords: Internship and residency, outcome assessment (health care), patient safety, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

The healthcare reimbursement structure is transitioning from one based on quantity (fee for service) to one based on quality (fee for value). Institutions positioned to provide high-quality patient care with improved patient safety and enhanced outcomes will become successful leaders in healthcare delivery. All hospital systems should strive to embrace and achieve these goals. However, significant barriers exist, and changes in culture and philosophy do not occur as quickly as desired.

In line with this quality-based movement, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires residents to have an educational experience in quality improvement during their training period. Meeting this mandate can be challenging, especially for smaller programs without extensive resources for quality improvement or available faculty time to engage in quality projects.1 Some programs have interpreted the requirement to mean that every resident must complete his or her own quality improvement project; however, this approach is not ideal. Parallel projects can lead to a multitude of concurrent changes that can overwhelm providers and adversely affect their attitudes about quality improvement or an already-limited supply of resources. Unfortunately, such problems can destruct good projects with the potential for meaningful outcomes.2

Historically, resident involvement in quality programs has not been robust. Nationally, only 32% of faculty and 29% of residents participate in institutional quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.3 Many institutions have engaged residents in patient safety and quality improvement training modules that emphasize a systems-based approach,2 but these programs do not place quality improvement directly into the hands of residents so they can learn how to physically implement changes. Other projects have included house staff in institutional quality initiatives4 but have struggled to involve residents beyond the department level. Therefore, strategies for the optimal incorporation of an integrated and collaborative resident quality experience with the overall hospital's institutional goals are needed.

The Alliance of Independent Academic Medical Centers (AIAMC) National Initiative (NI) is a multiinstitutional effort to unite academic medical education with hospital quality and safety strategies.5 Thirty-eight institutions participated in the most recent National Initiative, NI III: Improving Patient Care through Medical Education. The main goal for the NI III project at Scott & White Memorial Hospital (SWMH) was to actively engage house staff in quality improvement projects by providing education, mentorship, and analytical tools while developing a culture of quality and safety on a hospitalwide and individual level.

Acceptance into the AIAMC NI III program was based on the development of a faculty-mentored house staff quality council (HSQC). Our HSQC model was an adaptation of a similar council at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.6-7 The New York-Presbyterian project was the first of its kind to integrate resident education with involvement in hospital-based quality and safety initiatives. Although this council achieved great success, similar councils have been slow to develop nationally. In this article, we describe SWMH's HSQC, including its development, implementation, successes, and lessons learned.

FORMATION OF A HOUSE STAFF QUALITY COUNCIL

SWMH is a 635-bed tertiary care center with 35 ACGME and 17 non-ACGME residency and fellowship programs. Collectively, we have more than 450 active resident house staff on campus. SWMH is affiliated with the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine. Although our institution is dedicated to healthcare improvement through quality and safety initiatives, historically, resident involvement has been sporadic and without structure or sustainability. The idea to develop a quality council was initially presented to leaders in graduate medical education, department chairs, and residency and fellowship program directors for endorsement and feedback on strategies to ensure the council's efficacy and sustainability.

In March 2012, all residents and fellows were invited to apply for a position on the council during its inaugural year. Candidates completed an application (Table 1) and furnished a curriculum vitae and letter of support from their program director. Twelve residents and fellows were selected after review of the self-nominated applications (Figure 1). Selection was based on prior quality improvement experience and/or expressed interest in quality and safety initiatives. Under the guidance of faculty mentors, the HSQC members organized the council and aligned its goals with those of the institution. Led by a chair and vice-chair, the council developed a mission and vision statement (Table 2) along with the council charter (Figure 2). Educational classes in quality improvement and patient safety and the initial project selection followed.

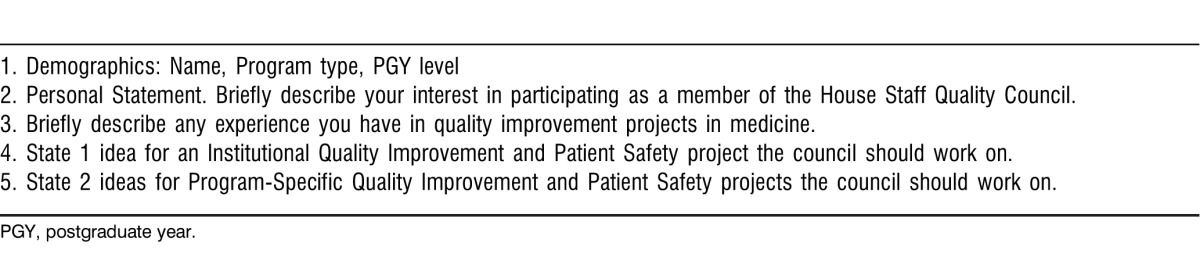

Table 1.

Application for the Scott & White Memorial Hospital House Staff Quality Council

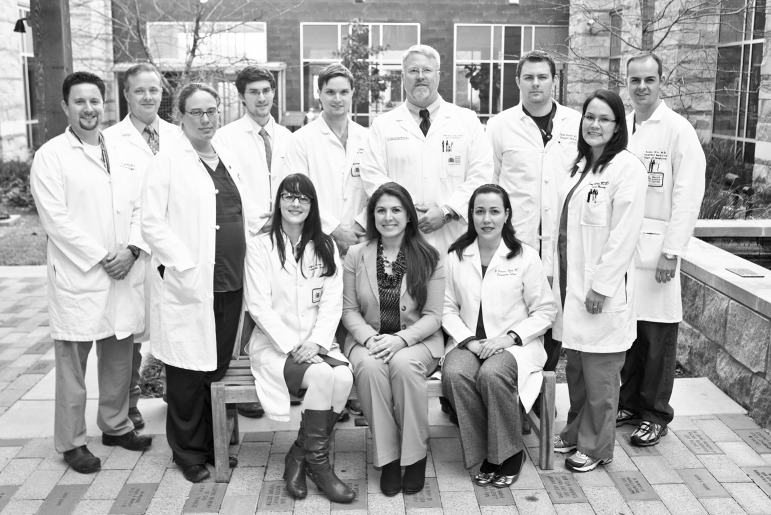

Figure 1.

Members of the inaugural Scott & White Memorial Hospital House Staff Quality Council (HSQC) are (from left to right, front row) Anna Best, MD (pathology); Jennifer Dixon, MD (general surgery, HSQC Chair); Hania Wehbe-Janek, PhD (mentor); Wilmary Rodriguez-Collado, MD (pulmonary and critical care); Sarah Hovland, MD, MPH (family medicine); (back row) Jason Campbell, DPM, MHA (podiatry); Russell McAllister, MD (mentor); Hayden Stagg, MD (general surgery); James Collins, MD (plastic surgery); John Erwin III, MD (mentor); Andrew Morris, DO (emergency medicine); and C. Scott Swendsen, MD (internal medicine, HSQC Vice-Chair). Members not pictured include Marri Brackman, DO (family medicine); Jeff Knabe, MD (orthopedic surgery); John Morelli, MD (radiology); Tiffany Berry, MD (mentor); Harry Papaconstantinou, MD (mentor).

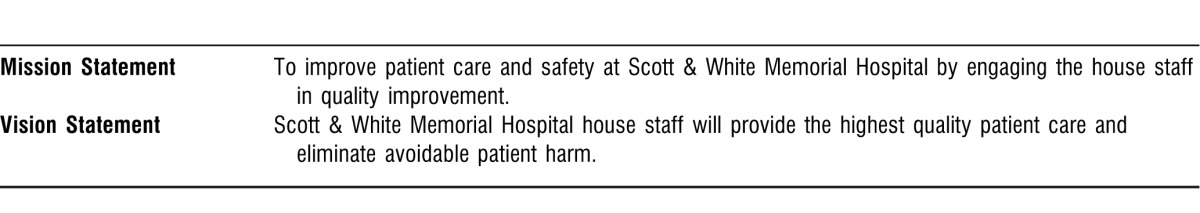

Table 2.

Mission and Vision for the House Staff Quality Council

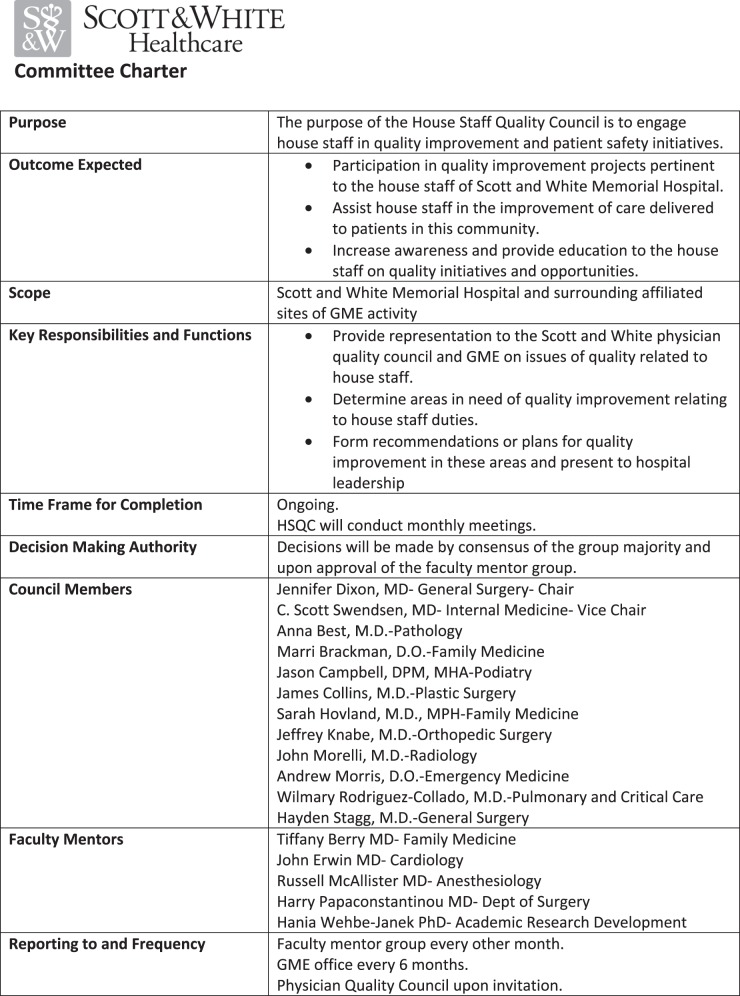

Figure 2.

Committee charter for the Scott & White Memorial Hospital House Staff Quality Council, 2012-2013.

Inaugural Year Activities

As a strong statement of institutional and resident commitment, SWMH enrolled all HSQC members in established process improvement training that uses the Toyota Lean methodology to build the skills necessary to develop and implement effective quality initiatives. Additionally, leaders in the quality improvement field gave brief presentations at the beginning of each meeting to further the members' educational development. To develop early momentum and because of the need to clearly define goals and prioritize projects, the council held bimonthly meetings for the first 2 months, followed by monthly meetings at which attendance continued to be greater than 50% of the membership.

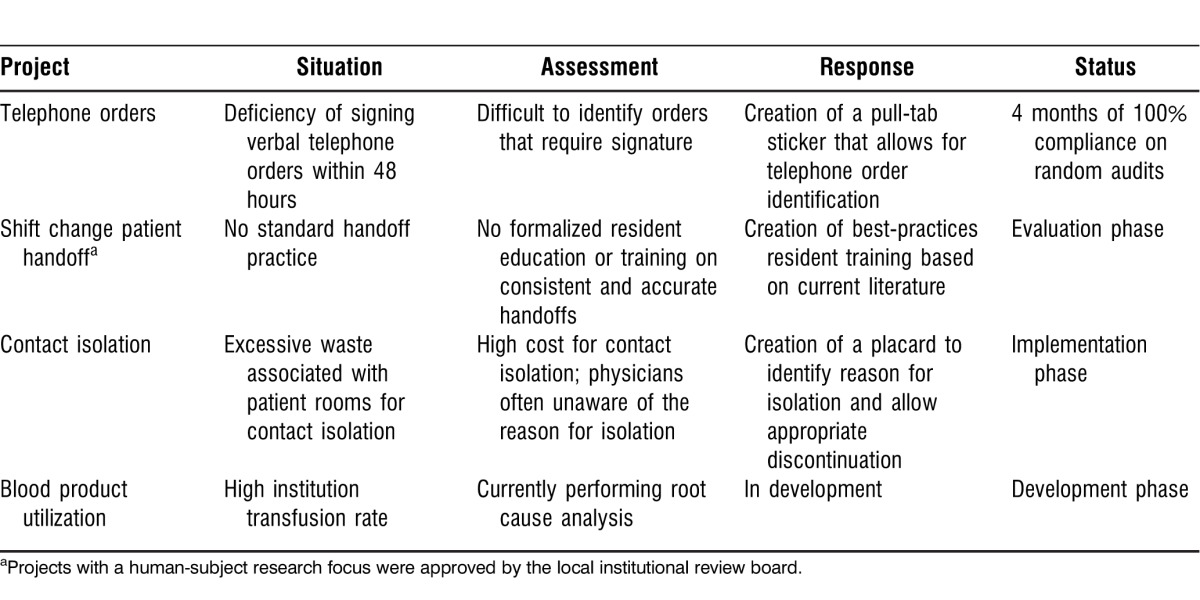

Projects started in the first year are listed in Table 3. For each project, council members performed background research and root cause analysis with the assistance of a coach. Through the quality improvement department, continuous learning improvement coaches assisted in defining measurable metrics and identifying target goals. The council and its initial projects were fully supported by the institution's chief medical officer who attended several of the council's meetings.

Table 3.

Scott & White Memorial Hospital House Staff Quality Council Initial Projects

Creating alliances with hospital groups already in existence was a focus of the first year. We had to systematically engage many nursing groups and leaders to prioritize projects and move them forward. Buy-in from nursing leadership was critical in developing many of the projects, although in some cases buy-in was slow to evolve. Support from high-level leadership within the institution—including the chief medical officer, the chief quality officer, and the chief nursing officer—was critical to success. Their involvement allowed effective integration and merging of HSQC members within established hospital leadership groups.

Barriers in the first year were expected and mainly consisted of concerns about gathering active residents together at one meeting time and their ability to balance the quality improvement projects with their clinical duties. We attempted to incorporate a member from each major specialty area (internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, etc.) for the council to be truly representative of the institution's entire house staff. However, establishing a universal meeting time for residents across such a large spectrum of specialties within the confines of work-hour regulations was difficult. Early in the process, we found that this barrier could be overcome by holding face-to-face meetings less frequently and performing most committee communication via email or in smaller subcommittee meetings.

The HSQC devised action plans for 3 of the initial projects during the inaugural year; the fourth project is in development. The HSQC's initial year culminated in the council chair's attendance at the annual AIAMC meeting where she led a presentation about the project.

We were pleased to have recruited and selected resident physicians who were highly motivated toward active participation and who maintained high attendance. We believe that the high degree of engagement was caused by resident volunteerism in the self-nominating application process. More than half of the participants are dedicated, contributing members who are working on several projects.

Sustainability

To ensure the council's continued success, the inaugural HSQC developed a sustainability plan endorsed by the faculty mentors. The plan addresses council membership, meeting attendance, and project involvement. Members may continue council involvement by renewing their annual commitment as long as they remain in a residency position, attend 50% or more of monthly meetings, and actively participate in 1 or more projects. Members are asked to hold council positions for subsequent years to allow for continuity and further development of the relationships between hospital leadership and council members. The number of years a council member may serve is only limited by the length of the participant's residency, and applicants may only apply for membership upon completion of their intern year. The chair and vice chair are selected by a majority vote from members who have served at least 1 year.

Additionally, the graduate medical education program directors' council approved our formal request to provide each council member with 4 hours of protected and dedicated time per month to work on HSQC-related projects, attend meetings, and/or pursue scholarly activities.

KEYS TO SUCCESS

The HSQC has been successful in initiating quality improvement projects that are pertinent to the house staff and patient care and are uniquely aligned with hospital quality goals. Our house staff have been motivated and empowered to complete projects and create meaningful change. A key component of our HSQC success and project implementation has been the multidisciplinary support, mentorship, and involvement from nursing and support staff. The mentor group actively challenges the council members to grow and pursue greater knowledge to enhance the successes they have achieved in improvement projects. The group has been embraced by hospital leadership and has shown itself to be a significant asset. The projects completed are meaningful and add value to the hospital by bringing together teams of frontline healthcare providers and staff for continuous quality improvement.

The HSQC development has been a successful endeavor in terms of resident-led patient safety and quality initiatives. As shown in Table 3, the council has had success in bringing projects to fruition. The first completed project addressed the problem of unsigned telephone orders. Current random hospital audits show dramatic improvement and 100% compliance because telephone orders are now identified by a pull-tab sticker. The shift change handoff project included a formal protocol and education process for residents. Resident satisfaction improved after the initiation of this program as measured by surveys in the departments of family medicine and internal medicine. Plans are now underway to expand the protocols and individualize them for all additional departments. The council is assisting the infection control department in its project to better identify patients in need of contact precautions. This project has been ideal for creating bonds with other hospital quality groups, which is critical for effective project implementation and success. The final project initiated by the HSQC involves the reduction of inappropriate blood product usage. Root cause analysis has been completed, and new protocols are being planned with the help of hospital faculty across several departments.

CONCLUSIONS

We attribute the success of our HSQC to high levels of faculty mentorship, strong support from hospital administrators, and resident council members dedicated to education and patient quality improvement.

Engaging residents with education and training in quality and patient safety tools serves as an asset for career development. Resident involvement in quality improvement projects has been correlated with continued interest and participation in these activities throughout their careers.8 Many current HSQC members have expressed interest in continuing quality work when they complete their training. Academic medical centers should consider the development of HSQCs to align institutional quality goals with residency training and medical education.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Systems-Based Practice, and Practice-Based Learning and Improvement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chase SM, Miller WL, Shaw E, Looney A, Crabtree BF. Meeting the challenge of practice quality improvement: a study of seven family medicine residency training practices. Acad Med. 2011 Dec;86(12):1583–1589. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823674fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voss JD, May NB, Schorling JB, et al. Changing conversations: teaching safety and quality in residency training. Acad Med. 2008 Nov;83(11):1080–1087. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818927f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigue C, Seoane L, Gala RB, Piazza J, Amedee RG. Developing a practical and sustainable faculty development program with a focus on teaching quality improvement and patient safety: an Alliance for Independent Academic Medical Centers National Initiative III project. Ochsner J. 2012 Winter;12(4):338–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stueven J, Sklar DP, Kaloostian P, et al. A resident-led institutional patient safety and quality improvement process. Am J Med Qual. 2012 Sep-Oct;27(5):369–376. doi: 10.1177/1062860611429387. Epub 2012 Feb 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alliance of Independent Academic Medical Centers. National Initiative. Improving Patient Care through Medical Education: a National Initiative of Independent Academic Medical Centers. 2013 http://www.aiamc.org/ni-phase-iii.php. Accessed March 22, [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleischut PM, Faggiani SL, Evans AS, et al. John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards. The effect of a novel Housestaff Quality Council on quality and patient safety. Innovation in patient safety and quality at the local level. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 Jul; 2011;38(7):311–317. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischut PM, Evans AS, Nugent WC, Faggiani SL, Kerr GE, Lazar EJ. Perspective: call to action: it is time for academic institutions to appoint a resident quality and patient safety officer. Acad Med. 2011 Jul;86(7):826–828. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821da286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz VA, Carek PJ, Johnson SP. Impact of quality improvement training during residency on current practice. Fam Med. 2012 Sep;44(8):569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]