Abstract

Brain cells die rapidly after stroke and any effective treatment must start as early as possible. In clinical routine, the tight time–outcome relationship continues to be the major limitation of therapeutic approaches: thrombolysis rates remain low across many countries, with most patients being treated at the late end of the therapeutic window. In addition, there is no neuroprotective therapy available, but some maintain that this concept may be valid if administered very early after stroke. Recent innovations have opened new perspectives for stroke diagnosis and treatment before the patient arrives at the hospital. These include stroke recognition by dispatchers and paramedics, mobile telemedicine for remote clinical examination and imaging, and integration of CT scanners and point-of-care laboratories in ambulances. Several clinical trials are now being performed in the prehospital setting testing prehospital delivery of neuroprotective, antihypertensive, and thrombolytic therapy. We hypothesize that these new approaches in prehospital stroke care will not only shorten time to treatment and improve outcome but will also facilitate hyperacute stroke research by increasing the number of study participants within an ultra-early time window. The potentials, pitfalls, and promises of advanced prehospital stroke care and research are discussed in this review.

Stroke has become a treatable disease: treatment with IV thrombolytics improves outcomes of acute ischemic stroke patients.1–4 Unfortunately, only a minority of eligible ischemic stroke patients receive recanalizing therapies.5

Recent developments in prehospital stroke management have revealed new perspectives for faster application of thrombolytic therapy. They have also reinvigorated research into neuroprotective drugs and therapies, which require administration very soon after stroke onset in order to preserve viable brain tissue. These innovations include the identification of stroke patients by dispatchers and by paramedics; collection and processing of informed consent to study participation via mobile cell phone and video; installation of modern diagnostics such as point-of-care laboratories, duplex sonography, and brain CT scanners in ambulances; and the integration of remote clinical examination and imaging review via mobile telemedicine as used for prehospital stroke thrombolysis in 2 current projects.6,7

As physicians who are involved in prehospital stroke research and whose aim is to further improve time-critical stroke treatments, we discuss the potentials, pitfalls, and promises of advanced prehospital stroke care and research.

THE “TIME IS BRAIN” RATIONALE OF ACUTE STROKE CARE

Following the occlusion of a cerebral artery, focal brain ischemia develops with gradients of reduced cerebral blood flow, which are most severe in the core of the lesion and more moderate in the perilesional zone. The so-called penumbra hypothesis states that the core of the focal ischemic lesion is irreversibly destined to die while the perilesional penumbra has lost its function due to reduced blood supply but has maintained metabolic and structural integrity and, hence, may be salvaged. Depending on site of arterial occlusion and collateral flow, the duration of perilesional penumbral survival may not be the same for all ischemic stroke subtypes. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence for the general association between time from onset and irreversible tissue damage—the so-called time is brain2 rationale. Indeed, research over the last 3 decades has identified a complex pathobiological cascade of events affecting the brain tissue over time and space unfolding excitotoxicity induced by massive presynaptic glutamate release, spreading depolarizations, inflammation, and delayed cell death mechanisms (apoptosis).8 However, while neuroprotective agents have reduced stroke lesion volumes and improved functional outcome in animal models, therapeutic efficacy has yet to be demonstrated in stroke patients,9 and many drug studies have thus far failed. This has sparked an intense scientific debate about this “translational roadblock.”10 While it is clear that early recanalization of an occluded vessel is a very effective means of salvaging tissue at risk for stroke, it is unclear whether any neuroprotective treatment is able to improve outcome without reperfusion. The concept of “freezing” the penumbra has been developed11: preserve brain tissue until blood supply is re-established.12 As intricate cascade of events occur within minutes rather than hours after stroke onset (e.g., presynaptic excitotoxic release of glutamate), classic neuroprotective treatment strategies may be effective only within the “golden hour,” i.e., within the first 60 to perhaps 90 minutes, or better still, the “diamond half hour,” i.e., within the first 30 minutes or less. Studying and treating large numbers of patients in this hyperacute time window requires optimized prehospital algorithms, which can hardly be achieved with standard posthospital-arrival pathways alone. Start of specific brain-protecting treatment has been shown to be effective in other diseases such as status epilepticus and hypoxia during cardiac arrest.13–15

DELAYS IN TIME TO TREATMENT—ALL LINKS OF THE RESCUE CHAIN ARE IMPORTANT

The efficacy of IV thrombolysis is a function of time: the earlier a stroke patient is treated, the greater the likelihood for a good recovery.2 Modeling of the potential for health gains from extension of the treatment time window for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has demonstrated that a majority of the population can gain substantially more from small reductions in onset to treatment time—for example, through improved prehospital notification and better in-hospital efficiency—than from extension of the window by 50% from 3 to 4.5 hours.16 Based on an adjusted analysis of the pooled randomized controlled IV tPA stroke trials, numbers needed to treat are only 4.5 within 90 minutes of onset but 9 between 91 and 180 minutes and 14 between 181 and 270 minutes.2 Unfortunately, data from stroke registries indicate that most patients who are treated within 3 hours of symptom onset receive tPA at a rather late time: median onset-to-treatment time was 140 minutes in Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke–Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST)17 and 146 minutes in the Get With the Guidelines Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) Registry.18 In either registry, more than half of the delays from onset to treatment were attributed to in-hospital procedures (mean door-to-needle times: 68 minutes in SITS-MOST and 78 minutes in GWTG-Stroke). Initiatives to optimize in-hospital procedures to achieve door-to-decision or door-to-needle times as low as 40 or even 20 minutes by introducing point-of-care laboratory test and streamlining procedures have been reported.19–21 However, even in those hospital systems with shortest door-to-needle times, onset-to-needle times remained relatively long (mean 13320 and 10821 minutes), usually due to long prehospital delays (mean onset-to-door time: 106 and 79 minutes, respectively). In order to achieve optimal reduction in onset-to-needle times, all steps of the stroke rescue chain need to be streamlined.

A major reason for long prehospital times is delay in seeking medical help either by the patient or by lay people witnessing the stroke. There have been multiple initiatives to improve stroke awareness with little evidence of effectiveness.22

Advanced notification to the receiving hospital by the Emergency Medical System (EMS) personnel of an inbound stroke patient permits early activation of the stroke team and readiness of in-hospital brain imaging facilities, and accelerates start of IV recombinant tPA after hospital arrival.23 Several stroke identification instruments have been developed and validated. They either enable dispatch centers24–26 to prioritize emergency services for stroke care27 or help EMS crews28–31 to prenotify hospital-based stroke teams. In order to shorten the time to treatment for a broad population, stroke needs to be prioritized both in EMS systems and in hospital organizations.

CURRENT APPROACHES TO ADVANCING PREHOSPITAL STROKE MANAGEMENT

Several projects are now initiating specific stroke workup before hospital arrival. They intend to improve triage to appropriate hospital facilities or to start treatment at the scene. Telemedicine with video examination of stroke patients in ambulances for earlier stroke recognition has been reported in 2 recent studies.32,33 While TeleStroke assessment appears feasible in general and has become routine care in many hospitals,34 data transmission based on the third-generation mobile communication technology currently available was not stable enough for routine use in the prehospital setting.33 The increasingly available fourth-generation technology is being tested in several regions and may offer major advantages by higher bandwidth (particularly in the upload stream) and by prioritizatized connection. Two studies are currently evaluating the potential of prehospital transcranial duplex sonography.35,36 If large cerebral artery occlusions can be detected before hospital arrival, patients could be admitted to specialized centers and in-hospital procedures could be accelerated by specific prenotification. However, feasibility of ultrasound examination is limited because reliability of this diagnostic method depends on the skills and experience of the investigator. The invention of simple helmet transducers and transmission of ultrasound imaging via telemedicine may facilitate the use of ultrasound in the future.37

A single-blind randomized trial recently completed in the United Kingdom assessed the feasibility of using ambulance services to recruit patients for ultra-acute stroke treatment trials and measured the effects of glyceryl trinitrate. Results of the trial are expected in the near future.38 The Paramedic-Initiated Lisinopril For Acute Stroke Treatment (PIL-FAST) pilot trial also focuses on feasibility of study recruitment in the prehospital setting.39 A small Finish study investigated the feasibility of administering subcutaneous insulin to control glucose in ambulances.40

Field Administration of Stroke Therapy–Magnesium (FAST-MAG), a major phase III neuroprotection trial with treatment start in the prehospital field, has completed recruitment in Los Angeles, California.41 Magnesium was chosen as the study drug for its presumed neuroprotective effects42 and had previously demonstrated safety in both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.43 The instruments being used in the study for prehospital stroke recognition28 and stroke severity rating44 are already part of the standard nationwide curriculum for paramedic stroke care and enabled competent training of the more than 3,300 participating paramedics in study procedures. A novel system for eliciting informed consent in the prehospital setting by remote physician-investigators via cell phone permitted study implementation without requiring paramedics to obtain repeated research ethics certification or imposing additional on-scene responsibilities.45

Magnesium was not found to be effective on the primary outcome in the Intravenous Magnesium Efficacy in Acute Stroke (IMAGES) trial,43 perhaps related to the long time window of 12 hours from stroke onset. In contrast to many previous trials with neuroprotective agents, the application of magnesium occurs within 2 hours of onset in all FAST-MAG patients, and within the first “golden hour” in 72%.46 More than 35% of acute ischemic stroke patients in FAST-MAG have received IV tPA in hospital after start of study agent infusion in the field, so the trial will have substantial power to test the hypothesis that magnesium preserves the penumbra until recanalizing therapies are started in-hospital.47

Two projects in Germany were primarily designed to target time to treatment in IV thrombolysis. Exclusion of intracranial hemorrhage is mandatory and coagulation tests are highly desirable before thrombolytic treatment. Both projects use portable CT scanners and point-of-care laboratory for prehospital stroke workup. The Mobile Stroke Unit project of the University of Homburg, Saarland, Germany, was first in installing such a CT scanner and point-of-care laboratory on an emergency vehicle.48 tPA treatment can be started at scene after exclusion of intracranial hemorrhage and coagulopathies48 and patients are then transported to hospital in a normal ambulance. The results of the controlled study show a remarkable reduction of time from alarm to therapy decision (median 35 minutes compared to 76 minutes in regular care).7 Time to treatment in those 12 patients who received tPA was approximately halved and onset-to-treatment time was only 72 minutes (median). However, scanning failures (mainly technical) were reported in a relevant number of patients (12 of 53).

The Stroke Emergency Mobile (STEMO) project of the Charité in Berlin has added new features.49 The scanner and point-of-care laboratory are installed in a fully equipped ambulance enabling hyperacute treatment and transport in the same vehicle (figure 1). During the scientific evaluation, STEMO is operated as an integrated ambulance of the Berlin emergency service and deployed when a previously validated stroke identification algorithm at the dispatch center yields a suspected acute stroke casualty.50 With the high number of approximately 3,000 strokes per year in a metropolitan area of 1.3 million people, STEMO is used with high frequency. The pilot study showed encouraging results for treatment safety and number of prehospital tPA applications (23 treatments within 52 days).6 The results from a large controlled study are expected in 2013.51

Figure 1. Stroke emergency mobile unit.

CT scanner on the left side; a separated shielded working station is placed on the right side including a point-of-care laboratory. The ambulance is used for immediate diagnostic workup and transportation of patients under intensive care conditions.

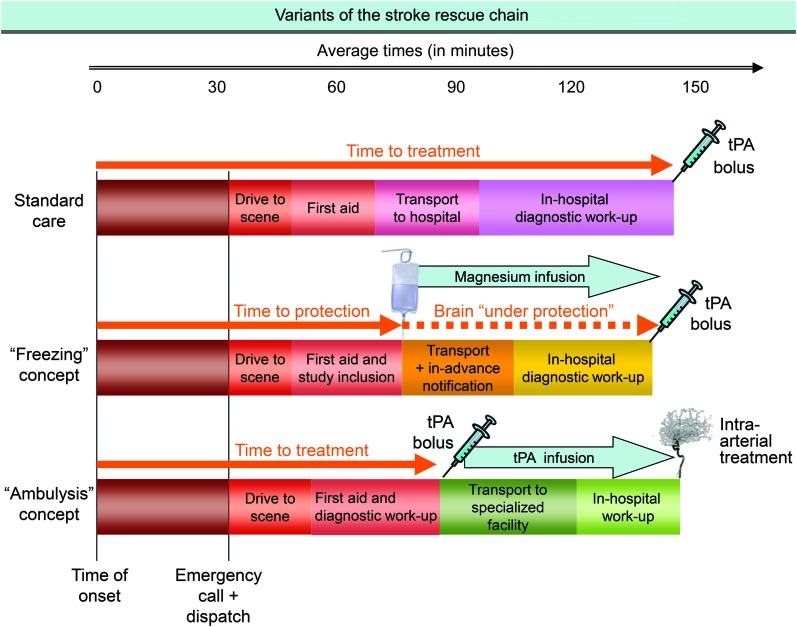

The different approaches of pre- and in-hospital stroke management are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Different approaches of pre- and in-hospital stroke management.

The first row represents standard care with hospital-based diagnostic workup and treatment. The second row illustrates the “freezing” concept like Field Administration of Stroke Therapy–Magnesium (FAST-MAG)44 with application of a neuroprotective agent by paramedics and delivery of patients after prenotification of hospital-based stroke teams. The third row exemplifies the “ambulysis”56 approach with prehospital brain imaging and point-of-care laboratory, starting IV thrombolysis in the field, and transport of patients to specialized facilities for interventional treatment (if indicated). tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.

While it is highly desirable to shorten stroke diagnosis and treatment times through prehospital management, we believe that there will be no “one-size-fits-all” approach: the preferred approach of prehospital stroke management will largely depend on existing EMS policies and available resources. In settings without physicians routinely working in the prehospital field, it might be more pragmatic to develop advanced prehospital management along with procedures that can be accomplished by paramedics as in the FAST-MAG trial.

In contrast, substantial infrastructural changes in the stroke rescue chain are needed to make stroke subtype-specific treatment approaches effective. The utilization of costly CT-equipped stroke ambulances can only be effective if a reasonably accurate stroke identification algorithm is in place at the dispatcher level. Otherwise, the specialized stroke ambulance will either not be used or will be called to a high number of patients with nonstroke diseases or strokes outside of the treatment window. Frequent and accurate deployment of the STEMO could only be realized after implementation of the prospectively validated Dispatcher Identification Algorithm for Stroke Emergencies (DIASE)50 with a sensitivity of 53% and positive predictive value of 48% for stroke.

At the moment, cost-effectiveness analyses are not available for any of the described approaches.

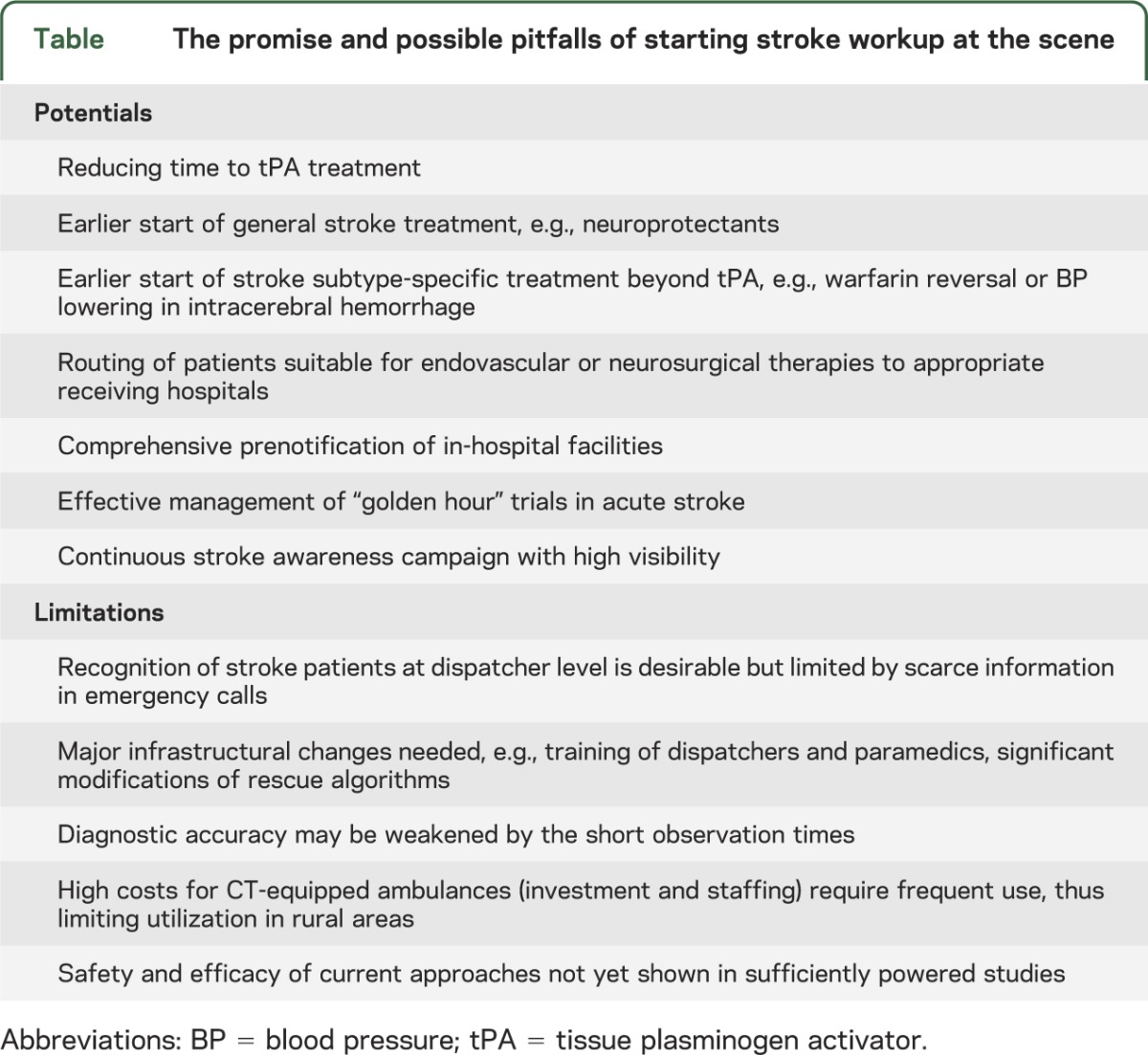

LIMITATIONS AND PITFALLS

See the table for limitations and pitfalls. The effective use of the new prehospital paramedic- and physician-delivered interventions depends on the recognition of stroke patients by dispatchers or ambulance staff. But even with best professional recognition, these approaches rely on stroke symptom awareness and preparedness of lay people who recognize stroke signs and call for EMS.52 Hence, despite limited evidence for their effectiveness, public stroke awareness campaigns will remain important for prehospital stroke care to be effective.22

Table.

The promise and possible pitfalls of starting stroke workup at the scene

Although at first glance CT-equipped ambulances may seem particularly suitable for rural regions, wide distances to patient homes are likely to attenuate time benefits and low numbers of stroke incidents will probably not allow economic deployment. A possible solution for middle-sized cities and their suburbs may be a collaboration of local ambulances and a centrally stationed stroke emergency ambulance in a “greet-and-meet” system. Alternatively, a paramedic-based approach (like FAST-MAG) could be used but needs close cooperation with hospital facilities in the covered region.

As a consequence of the limited information provided in emergency calls, stroke recognition at dispatcher level will always be far from optimal. Consequently, all EMS vehicles will need to remain stroke capable even in systems that adopt mobile CT equipment.

Even with excellent stroke expertise available on ambulances, diagnosis of stroke and differentiation from stroke mimics may be less accurate than in-hospital. The clinical course of symptoms is one of the most important parts of clinical diagnosis, and is available over a more extended observation period in-hospital, but this is usually not the case at the scene.

So far, specific prehospital stroke treatments have not been performed in sufficient numbers to justify declaring them safe. Even with using established concepts like IV thrombolysis, treatment in the prehospital setting may bear risks higher than those in-hospital because of mechanical stress during transport and the more limited possibilities of monitoring and intervention.

Finally, with the changes in emergency service infrastructure needed for low- and high-tech approaches of prehospital care, and the significant costs for high-tech stroke ambulances, the implementation of the new systems into regular care is far from assured.

PREHOSPITAL STROKE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT: THE PROMISE OF FASTER AND BETTER TREATMENT NOT LIMITED TO IV tPA

Making hyperacute stroke workup available at the scene is projected not only to avoid transport delays but also to streamline the required procedures and provide a highly specialized team (consisting of a stroke physician, paramedic, and technician) with everything they need for acute stroke diagnosis and treatment.

Although time-dependent treatment effects are best shown for IV tPA treatment, prehospital stroke management may provide benefits beyond thrombolysis, as the following examples illustrate:

Hemorrhage: as growth of intracerebral hematoma is aggravated in patients under oral anticoagulation53 and rapid reversal of anticoagulation has been shown to attenuate this effect in animal experiments,54 immediate prehospital application of prothrombin complex concentrate may improve outcome of this subset of patients with otherwise poor prognosis. The same applies to blood pressure management in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. With earlier diagnosis of the hemorrhage by prehospital CT, lowering blood pressure according to guidelines55 can start before hospital arrival.56 Two pilot trials of lowering prehospital blood pressure are under way in the United Kingdom.39,57

Triage: prehospital stroke assessment using deficit severity scales may enable paramedics to identify patients likely to be harboring large-artery occlusions and to deliver them directly to centers qualified and equipped for endovascular recanalization interventions.44 Biomarkers may also be helpful in differentiating ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes when available as point-of-care tests.58 Detailed prehospital workup with CT angiography allows the determination of stroke subtype including definitive assessment of large-artery occlusion in ischemic stroke or vessel leak (so-called dot sign) in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. This information may assist prehospital triage of patients with targeted admission to specialized centers. Although evidence for acute interventional and surgical treatment of stroke is scarce, guidelines recommend considering these therapeutic options for specific stroke subtypes such as proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion59 (also in combination with bridging IV tPA) or intraventricular hemorrhage with occlusive hydrocephalus.55

PREHOSPITAL STROKE MANAGEMENT OPENS THE DOOR TO TREATMENT TRIALS IN THE GOLDEN HOUR

Allowing study inclusion and application of study drugs in the prehospital setting would open the door to early treatment windows of 60 (to maximally 90) minutes, a goal that could hardly be achieved in “conventional” hospital-based trials. Already in the FAST-MAG trial in a mixed ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke population, the median last-seen-well to study drug treatment time is 47 minutes. With newly available stroke identification algorithms at the dispatcher level,24,50 specialized stroke ambulances can encounter acute stroke patients at high frequency, facilitating prehospital trials in specific stroke subtypes. In fact, there are several examples where earlier treatment would increase the likelihood of a trial success: even failed approaches like activated factor VII administration in intracerebral hemorrhage60 may be tested in this new setting—a post hoc analysis of the FAST trial suggested that the drug was beneficial when applied within 150 minutes of symptom onset in a subset of patients.61

By admitting suitable patients to hospitals that run acute stroke trials, specialized stroke ambulances may also enhance recruitment of patients for trials that need specific hospital-based facilities such as MRI in mismatch-based or wake-up stroke studies62 or interventional neuroradiology for intra-arterial intervention.

OUTLOOK

The long held vision of hyperacute prehospital stroke treatment has become a reality as a result of the creation and validation of new EMS dispatcher and paramedic algorithms and scales and the implementation of stroke ambulances equipped with imaging and laboratory technologies. These advances could make existing stroke treatments more effective and help to develop new therapeutic strategies. However, it is clear that these innovations will not replace but rather complement existing prehospital and in-hospital stroke care strategies.

At the moment, neither safety nor clinical nor cost-effectiveness data have been shown for any of these new approaches. While perspectives look promising in this upcoming field, systematic research is needed to assess their real value.

GLOSSARY

- DIASE

Dispatcher Identification Algorithm for Stroke Emergencies

- EMS

Emergency Medical System

- GWTG-Stroke

Get With the Guidelines Stroke

- PIL-FAST

Paramedic-Initiated Lisinopril For Acute Stroke Treatment

- FAST-MAG

Field Administration of Stroke Therapy–Magnesium

- IMAGES

Intravenous Magnesium Efficacy in Acute Stroke

- SITS-MOST

Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke–Monitoring Study

- STEMO

Stroke Emergency Mobile

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Heinrich J. Audebert, MD: initiation of the joint manuscript, draft of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Jeffrey Saver, MD: drafting parts of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Sidney Starkman, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Kennedy R. Lees, MD: drafting parts of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Matthias Endres, MD: drafting parts of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE

H.J. Audebert is an employee of the Charité Universitätsmedizin and is an investigator in the Center for Stroke Research Berlin (CSB), which receives funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Berlin Technology Foundation (with cofunding by the EU within the European Regional Development Fund [ERDF]). He reports consultancy honoraria by Lundbeck Pharma, Pfizer, and Bayer Vital as well as speaker honoraria from Takeda Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Bayer Vital, Roche, UCB Pharma, and Sanofi. J.L. Saver is an employee of the University of California, Regents, which holds a patent on retriever devices for stroke. He is an investigator in the NIH MR and Recanalization of Stroke Clots Using Embolectomy (MR RESCUE) and International Management of Stroke (IMS) 3 multicenter clinical trials, for which the UC Regents receive payments based on clinical trial performance; has served as an unpaid site investigator in multicenter trials run by ev3, for which the UC Regents received payments based on the clinical trial contracts for the number of subjects enrolled; and was an unpaid site investigator in a multicenter registry run by Concentric, for which the UC Regents received payments based on the clinical trial contracts for the number of subjects enrolled. The University of California, Regents, receives funding for the services of J.L.S. as scientific consultant regarding trial design and conduct to ev3 and Chestnut Medical. S. Starkman is an employee of the University of California, Regents, which holds a patent on retriever devices for stroke. He is an investigator in the NIH MR RESCUE and International Management of Stroke (IMS) 3 multicenter clinical trials, for which the UC Regents receive payments based on clinical trial performance; has served as an unpaid site investigator in multicenter trials run by ev3, for which the UC Regents received payments based on the clinical trial contracts for the number of subjects enrolled; and is a paid site investigator in a multicenter registry run by Concentric, for which the UC Regents received payments based on the clinical trial contracts for the number of subjects enrolled. K.R. Lees has chaired data monitoring committees for sponsors of studies in acute stroke, including Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferrer, Glasgow Biomedicine, Grifols, Lundbeck, and PhotoThera; and has received speakers fees from Boehringer Ingelheim. His department receives research funding from the European Union Framework 7 program (FP7), Genentech, and the NIH. M. Endres is an employee of the Charité Universitätsmedizin and is an investigator in the CSB, which receives funding from the BMBF and the Berlin Technology Foundation (with cofunding by the EU within the ERDF). He has received grant support from AstraZeneca, Roche, and Sanofi, has participated in advisory board meetings of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Pfizer, and Sanofi, and has received honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Berlin Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Desitin, Eisei, Ever, Glaxo Smith Kline, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Takeda, and Trommsdorff. He receives funding from the DFG (Excellence cluster NeuroCure; SFB TR 43, KFO 247, KFO 213), BMBF (Center for Stroke Research Berlin), EU (Eustroke, ARISE, WakeUp), Volkswagen Foundation (Lichtenberg Program), and Corona Foundation. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet 2010;375:1695–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1317–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandercock P, Wardlaw JM, Lindley RI, et al. The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:2352–2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leys D, Ringelstein EB, Kaste M, Hacke W. Facilities available in European hospitals treating stroke patients. Stroke 2007;38:2985–2991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber JE, Ebinger M, Rozanski M, et al. Prehospital thrombolysis in acute stroke: results of the PHANTOM-S pilot study. Neurology 2013;80:163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter S, Kostopoulos P, Haass A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with stroke in a mobile stroke unit versus in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci 1999;22:391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Collins VE, Macleod MR, Donnan GA, et al. 1,026 experimental treatments in acute stroke. Ann Neurol 2006;59:467–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endres M, Engelhardt B, Koistinaho J, et al. Improving outcome after stroke: overcoming the translational roadblock. Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;25:268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murata Y, Rosell A, Scannevin RH, et al. Extension of the thrombolytic time window with minocycline in experimental stroke. Stroke 2008;39:3372–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnan GA, Baron JC, Ma H, Davis SM. Penumbral selection of patients for trials of acute stroke therapy. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 2001;345:631–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2002;346:549–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James M, Monks T, Pitt M, Stein K. Increasing the Proportion of patients treated with thrombolysis: reducing in-hospital delays has substantially more Impact than extension of the time window. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;(suppl 2):p602–p603 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Davalos A, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3-4.5 h after acute ischaemic stroke (SITS-ISTR): an observational study. Lancet 2008;372:1303–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation 2011;123:750–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter S, Kostopoulos P, Haass A, et al. Point-of-care laboratory halves door-to-therapy-decision time in acute stroke. Ann Neurol 2011;69:581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meretoja A, Strbian D, Mustanoja S, et al. Reducing in-hospital delay to 20 minutes in stroke thrombolysis. Neurology 2012;79:306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohrmann M, Schellinger PD, Breuer L, et al. Avoiding in hospital delays and eliminating the three-hour effect in thrombolysis for stroke. Int J Stroke 2011;6:493–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecouturier J, Rodgers H, Murtagh MJ, et al. Systematic review of mass media interventions designed to improve public recognition of stroke symptoms, emergency response and early treatment. BMC Public Health 2010;10:784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin CB, Peterson ED, Smith EE, et al. Emergency medical service hospital prenotification is associated with improved evaluation and treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:514–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buck BH, Starkman S, Eckstein M, et al. Dispatcher recognition of stroke using the National Academy Medical Priority Dispatch System. Stroke 2009;40:2027–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Govindarajan P, Ghilarducci D, McCulloch C, et al. Comparative evaluation of stroke triage algorithms for emergency medical dispatchers (MeDS): prospective cohort study protocol. BMC Neurol 2011;11:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramanujam P, Guluma KZ, Castillo EM, et al. Accuracy of stroke recognition by emergency medical dispatchers and paramedics–San Diego experience. Prehosp Emerg Care 2008;12:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berglund A, Svensson L, Sjostrand C, et al. Higher prehospital priority level of stroke improves thrombolysis frequency and time to stroke unit: the Hyper Acute STroke Alarm (HASTA) study. Stroke 2012;43:2666–2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kidwell CS, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Weems K, Saver JL. Identifying stroke in the field. Prospective validation of the Los Angeles prehospital stroke screen (LAPSS). Stroke 2000;31:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bray JE, Martin J, Cooper G, et al. Paramedic identification of stroke: community validation of the Melbourne ambulance stroke screen. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005;20:28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, Brott T, Broderick J. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harbison J, Hossain O, Jenkinson D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of stroke referrals from primary care, emergency room physicians, and ambulance staff using the face arm speech test. Stroke 2003;34:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergrath S, Reich A, Rossaint R, et al. Feasibility of prehospital teleconsultation in acute stroke: a pilot study in clinical routine. PLoS One 2012;7:e36796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liman TG, Winter B, Waldschmidt C, et al. Telestroke ambulances in prehospital stroke management: concept and pilot feasibility study. Stroke 2012;43:2086–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Audebert HJ, Kukla C, Clarmann von Claranau S, et al. Telemedicine for safe and extended use of thrombolysis in stroke: the Telemedic Pilot Project for Integrative Stroke Care (TEMPiS) in Bavaria. Stroke 2005;36:287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlachetzki F, Herzberg M, Holscher T, et al. Transcranial ultrasound from diagnosis to early stroke treatment: part 2: prehospital neurosonography in patients with acute stroke: the Regensburg stroke mobile project. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;33:262–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prehospital Transcranial Duplex in Patients with Acute Stroke. 2012. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01069276. Accessed April 29, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holscher T, Dunford JV, Schlachetzki F, et al. Prehospital stroke diagnosis and treatment in ambulances and helicopters-a concept paper. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:743–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ankolekar S, Sare G, Geeganage C, et al. Determining the feasibility of ambulance-based randomised controlled trials in patients with ultra-acute stroke: study protocol for the Rapid Intervention with GTN in Hypertensive Stroke Trial (RIGHT, ISRCTN66434824). Stroke Res Treat 2012;2012:385753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw L, Price C, McLure S, et al. Paramedic Initiated Lisinopril For Acute Stroke Treatment (PIL-FAST): study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials 2011;12:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nurmi J, Lindsberg PJ, Happola O, et al. Strict glucose control after acute stroke can be provided in the prehospital setting. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:436–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Field Administration of Stroke Therapy–Magnesium (FAST-MAG) trial. 2012. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00059332. Accessed May 3, 2012

- 42.Izumi Y, Roussel S, Pinard E, Seylaz J. Reduction of infarct volume by magnesium after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1991;11:1025–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muir KW, Lees KR, Ford I, Davis S. Magnesium for acute stroke (Intravenous Magnesium Efficacy in Stroke trial): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nazliel B, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS, et al. A brief prehospital stroke severity scale identifies ischemic stroke patients harboring persisting large arterial occlusions. Stroke 2008;39:2264–2267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanossian N, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS, et al. Simultaneous ring voice-over-Internet phone system enables rapid physician elicitation of explicit informed consent in prehospital stroke treatment trials. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;28:539–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saver JL, Eckstein M, Stratton S, Pratt F, et al. ; for the FAST-MAG Investigators and Nurse-Coordinators Field Administration of Stroke Therapy–Magnesium (FAST-MAG) Phase 3 Trial. Ongoing Clinical Trial Poster Session Abstract Booklet. New Orleans: International Stroke Conference; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanossian NK-TM, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS, et al. ; for the FAST-MAG Investigators and Coordinators Field neuroprotective therapy followed by intravenous thrombolysis in a phase 3 clinical trial. Stroke 2012;43:A65 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fassbender K, Walter S, Liu Y, et al. "Mobile stroke unit" for hyperacute stroke treatment. Stroke 2003;34:e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.PHANTOM-S. The pre-hospital acute neurological therapy and optimization of medical care in stroke patients study. 2012. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01382862. Accessed April 29, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krebes S, Ebinger M, Baumann AM, et al. Development and validation of a dispatcher identification algorithm for stroke emergencies. Stroke 2012;43:776–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ebinger M, Rozanski M, Waldschmidt C, et al. PHANTOM-S: the prehospital acute neurological therapy and optimization of medical care in stroke patients study. Int J Stroke 2012;7:348–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodgson C, Lindsay P, Rubini F. Can mass media influence emergency department visits for stroke? Stroke 2007;38:2115–2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flibotte JJ, Hagan N, O'Donnell J, Greenberg SM, Rosand J. Warfarin, hematoma expansion, and outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2004;63:1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun L, Zhou W, Ploen R, et al. Rapid reversal of anticoagulation prevents excessive secondary hemorrhage after thrombolysis in a thromboembolic model in rats. Stroke 2011;42:3524–3529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, 3rd, Anderson C, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2010;41:2108–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kostopoulos P, Walter S, Haass A, et al. Mobile stroke unit for diagnosis-based triage of persons with suspected stroke. Neurology 2012;78:1849–1852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bath P. RT: The RIGHT Trial: Rapid Intervention with Glyceryl Trinitrate (GTN) in Hypertensive Stroke; ISRCTN66434824. 2012. Available at: http://www.right-trial.org/rightprotocolv11.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foerch C, Niessner M, Back T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein for differentiating intracerebral hemorrhage and cerebral ischemia in patients with symptoms of acute stroke. Clin Chem 2012;58:237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams HP, Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation 2007;115:e478–e534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2127–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayer SA, Davis SM, Skolnick BE, et al. Can a subset of intracerebral hemorrhage patients benefit from hemostatic therapy with recombinant activated factor VII? Stroke 2009;40:833–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Efficacy and safety of MRI-based thrombolysis in wake-up stroke (WAKE-UP). Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01525290?term=wake-up&rank=1. Accessed June 15, 2012.