Abstract

Objective:

We determined the rate of falls among cognitively normal, community-dwelling older adults, some of whom had presumptive preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD) as detected by in vivo imaging of fibrillar amyloid plaques using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and PET and/or by assays of CSF to identify Aβ42, tau, and phosphorylated tau.

Methods:

We conducted a 12-month prospective cohort study to examine the cumulative incidence of falls. Participants were evaluated clinically and underwent PiB PET imaging and lumbar puncture. Falls were reported monthly using an individualized calendar journal returned by mail. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to test whether time to first fall was associated with each biomarker and the ratio of CSF tau/Aβ42 and CSF phosphorylated tau/Aβ42, after adjustment for common fall risk factors.

Results:

The sample (n = 125) was predominately female (62.4%) and white (96%) with a mean age of 74.4 years. When controlled for ability to perform activities of daily living, higher levels of PiB retention (hazard ratio = 2.95 [95% confidence interval 1.01–6.45], p = 0.05) and of CSF biomarker ratios (p < 0.001) were associated with a faster time to first fall.

Conclusions:

Presumptive preclinical AD is a risk factor for falls in older adults. This study suggests that subtle noncognitive changes that predispose older adults to falls are associated with AD and may precede detectable cognitive changes.

Falls remain the leading cause of long-term disability, premature institutionalization, injury, and injury-related mortality in the older adult population.1 Persons with Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia have an increased risk of serious falls.2 Gait changes and falls have been associated with non-AD dementias.3 However, gait change may also be associated with AD and may precede cognitive changes.4,5 New guidelines and diagnostic criteria for AD6 now recognize a preclinical phase of the disease, detectable with imaging and CSF biomarkers.7 There are hypothesized models of ordered change in validated biomarkers that occur during the AD process.8 Only limited data have been available to indicate that cognitively normal older adults with positive AD biomarkers of presumptive preclinical AD are at increased risk of developing cognitive impairment and dementia.9,10 However, a stage of preclinical AD has been validated by AD biomarkers in asymptomatic individuals who carry a deterministic mutation for AD.11 By definition, older adults with presumptive preclinical AD do not have cognitive symptoms as recognized by current clinical methods. However, other changes may be detectable and could yield important information about the spectrum of clinical features of the disease. Physical changes such as weight loss12 and frailty13 have been identified in cognitively normal individuals who later develop AD dementia. Because motor slowing precedes cognitive impairment during the typical aging process,14,15 it is possible that preclinical AD could exacerbate this motor dysfunction and lead to an increased risk of falls.

METHODS

We examined the rate of falls in an existing cohort of cognitively normal, community-dwelling older adults, some of whom had preclinical AD as detected by CSF and imaging biomarkers. We hypothesized that cognitively normal older adults with preclinical AD would have a greater cumulative incidence of falls compared with cognitively healthy older adults without preclinical AD.

Overview and setting.

A 12-month prospective cohort study examined the cumulative incidence of falls among cognitively normal older adults, with and without preclinical AD, who participate in longitudinal studies of memory and aging at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis. Preclinical AD was determined based on biomarker results (see below). Fall status was ascertained monthly using a tailored calendar journal and fall hotline (see below). Recruitment and follow-up occurred from May 2010 until November 2011.

Participants.

Detailed information regarding recruitment, enrollment, and clinical assessment of the participants has been published.12 Briefly, participants are community-dwelling individuals without health conditions that could adversely affect longitudinal participation (e.g., renal failure requiring dialysis). Each participant receives an annual clinical assessment. Participants in the longitudinal studies undergo in vivo imaging of fibrillar amyloid plaques using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and PET16 and lumbar puncture (LP) to provide CSF samples.9

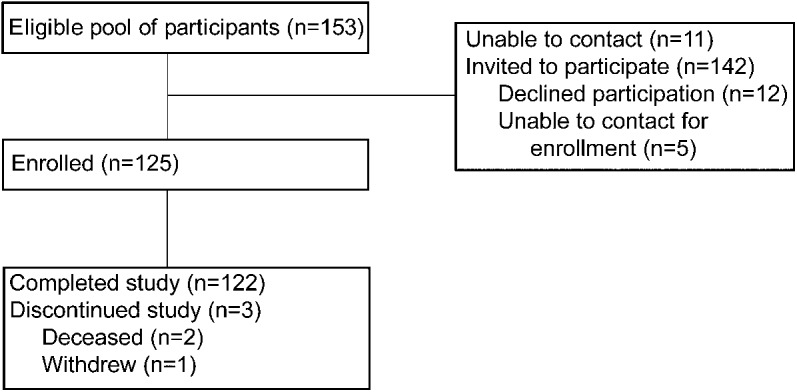

We invited individuals to participate in the current study if they met the following criteria: 1) age 65 years or older; 2) normal cognition as indicated by Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 017 at their most recent clinical and cognitive assessment; and 3) completed an imaging study within 1 year of that assessment and/or an LP to obtain CSF within 3 years of the assessment. Of the 153 participants who met eligibility criteria, 142 were able to be contacted for enrollment in this study. Five of these participants did not respond to further telephone contact attempts. After a telephone interview, 12 participants declined to consent. The final sample included 125 participants. Participants received a $5 grocery store gift card for each month they participated in the study. Two participants died during the follow-up period. One participant was lost to follow-up after the death of his spouse (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent.

Study protocols were approved by the Washington University Medical Center Human Subjects Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Materials.

Clinical examination.

During the clinical examination, experienced clinicians (neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, and geriatricians all trained in all assessment procedures by J.C.M.) interviewed the participant and a collateral source using a standardized protocol to generate a CDR.17 The CDR is determined based on performance in 6 domains—memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care—and has established reliability.18 CDR scores range from 0 (cognitive normality) to 3 (severe dementia). In individuals with CDR >0, the diagnosis of AD dementia and other dementing conditions is made in accordance with standard criteria.19 However, all participants in this study were CDR 0 at their entry into the study. The Mini-Mental State Examination20 is administered during the clinical examination. A neurologic examination characterizes gait as either normal or abnormal.

Psychometric assessment.

A 1.5-hour psychometric assessment is conducted according to a standard protocol21 a few weeks after the clinical assessment. Individual measures in the test battery include Logical Memory and Associate Learning from the Wechsler Memory Scale22 and the Free and Selective Reminding Test (sum of 3 free recall trials)23 to evaluate episodic memory; information from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale24 and the Boston Naming Test25 to evaluate semantic memory; Mental Control and Digit Span (forward and backward) from the Wechsler Memory Scale19 and Word Fluency for the letters s and p26 to evaluate working memory; and Block Design and Digit Symbol from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale24 and the Trail Making Test A27 to measure visuospatial ability and speeded psychomotor performance. Scores are converted to z scores using means and SDs from the initial assessment of a reference group of 310 participants who had a CDR of 0 at enrollment and throughout follow-up and had at least 2 follow-up assessments.21 These z scores were then averaged to form composites that represent the cognitive domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial abilities; and speeded psychometric performance.21

Biomarkers.

In vivo amyloid imaging was completed using a standard protocol that has been described in detail.28 Briefly, the PET imaging was conducted with a Siemens 961 HR ECAT scanner or a Siemens 962 HR + ECAT scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN). The PiB image analysis was achieved by registering each participant's PET PiB image set to a magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient echo MRI. Three-dimensional regions of interest (ROIs) were applied to images of the PET dynamic data, yielding regional time-activity curves.28 These curves were analyzed for PiB-specific binding using the Logan graphical analysis, with the cerebellum as reference.29 The Logan analysis yielded a tracer distribution volume ratio, which was then converted to an estimate of the binding potential (BP) for each ROI: BP = distribution volume ratio − 1. The BP expresses regional PiB binding values in a manner directly proportional to the number of binding sites. The BP values from the prefrontal cortex, gyrus rectus, lateral temporal cortex, and precuneus ROIs were averaged in each participant to calculate the mean cortical BP (MCBP).28

CSF (20–30 mL) was collected via an LP in the morning after an overnight fast following a standard protocol that has been reported elsewhere.9 Samples were gently inverted to avoid possible gradient effects, briefly centrifuged at low speed, and aliquoted into polypropylene tubes before freezing at –84°C.9 Samples were analyzed for total tau, phosphorylated tau181 (ptau181), and Aβ42 using an ELISA (Innotest; Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium).

Fall covariates.

Upon enrolling in the fall study, each subject participated in a 10- to 15-minute telephone interview to ascertain covariates shown in previous studies to be related to falls. Alcohol abuse was measured using the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test–Geriatric Version,30 a 10-item interview validated for the older adult population. Scores of 2 or more are indicative of a probable alcohol problem.30 Limitations in the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL have been associated with an increased risk of falls. The Older American Resources and Services ADL scale was used to determine individuals' level of ADL/instrumental ADL impairment.31 The Older American Resources and Services scale is brief and easy to administer over the telephone. Respondents are asked about their ability to perform 14 activities, and responses are scored on a 0–2 scale, with higher scores indicating greater independence. Vision and number of prescription medications were assessed. Vision was screened using the question from the National Health Interview Survey: “In the past 12 months, have you had trouble seeing even when wearing glasses or contact lenses (yes or no)?”32 Prescription medications and dosages were reported by the participant; total number of medications used on a monthly basis was summed.

Prospective fall ascertainment.

A 12-month calendar journal, tailored with birthdays and other important personal dates, was produced for each participant to record whether or not a fall occurred daily. Personal dates were provided as a cue to help accurately recall when a fall event occurred. Each page of the 4.25” × 5.5” large-print calendar journal had space to record 1 week's fall outcome on each page. The calendar journal included fall survey pages to record details of a fall.

Upon receipt of the calendar journal in the mail, participants underwent a telephonic training session to learn to accurately use the calendar journal. Instruction was provided for where to place the journal, how to record details of falls using a fall form, and how to return calendar journal pages each month. Falls were defined as unintentional movement to the floor, the ground, or an object below knee level.33

We monitored fall documents and ascertained details of falls monthly as recommended by the Prevention of Falls Network Europe.33 Participants were mailed a reminder to return their calendar pages each month using a provided self-addressed stamped envelope. Pages not returned within 1 week of the due date or that were incomplete prompted a telephone call to the participant. Upon receipt of the pages, a $5 gift card was mailed. A report of a fall triggered a telephone interview to verify that the reported fall met the definition and to ascertain details of the fall. Participants who did not want to record the fall using the calendar journal were given the option of answering the journal questions via telephone with the study coordinator.

Statistical analysis.

Time to the first fall was operationalized as days enrolled in study to the first fall. Ratios of tau/Aβ42 and ptau/Aβ42 were calculated.9 High and low groups were constructed for all 4 biomarkers and the 2 ratios with the most extreme quartile were assigned as high for that variable.

The log-rank test was used to compare the Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the time to the first fall in the 2 groups for each biomarker and the ratios of tau/Aβ42 and ptau/Aβ42. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated using a Cox proportional hazards model with fall covariates including age, ADL ability, and number of medications with the PHREG procedure of SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Covariates that were statistically associated with time to fall (p < 0.05) were retained in the model. Time to first fall was tested for association with MCBP at baseline, after adjustment for fall risk factors. Each of the hypothesized potentially confounding variables—age, sex, number of medications, alcohol abuse, and ADL performance—was modeled to allow estimation of fall risk while holding the variable constant. Similar analyses were conducted for each of the CSF biomarkers, as well as the ratio of tau/Aβ42 and ptau/Aβ42. Only the addition of ADL performance improved the crude models. Therefore, the final models included ADL performance. In the survival analyses, data from participants who had no falls over the follow-up period were censored at 365 days. These comparisons were designed into the experiment, and not decided upon after inspecting the data. No adjustment was made for multiple testing. All p values are 2-sided to detect differences (p < 0.05).

RESULTS

There was no difference in demographic characteristics between those who enrolled in the study and those who declined. Data from 2 participants who died before completing the monitoring period were censored at that time (1 in month 7 and 1 in month 8). One participant was lost to follow-up upon the death of his spouse and was censored at that time (month 10). Of the enrolled participants, 119 had MCBP data and 88 had CSF data on biomarkers of Aβ42, tau, and ptau. There were 13 missing months of data (of 1,500 possible months) for a response rate of 99.1%; compliance excluding loss to follow-up due to death was calculated at 99.9%.

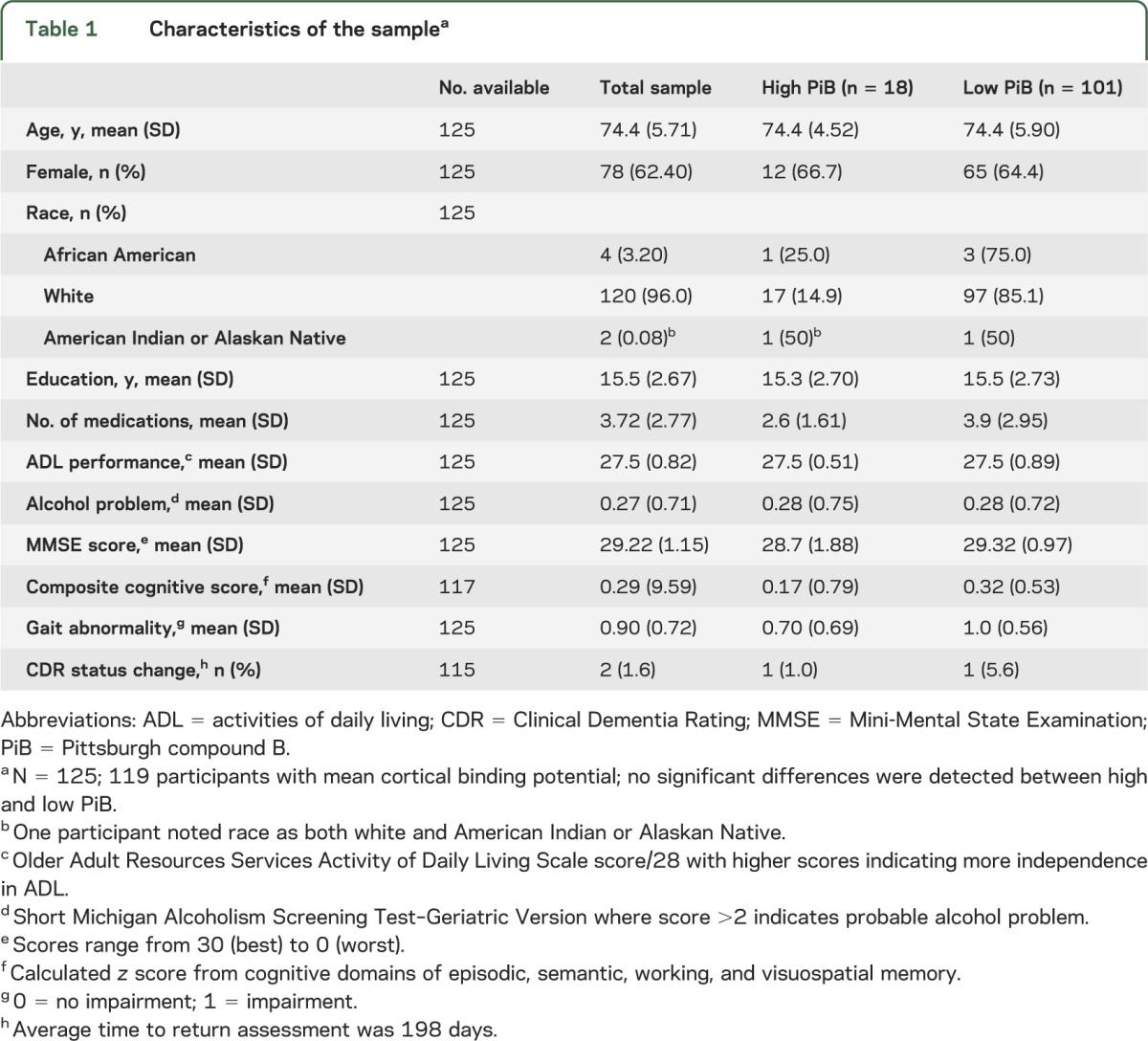

The low and high PiB uptake groups did not differ significantly by age, sex, years of education, number of medications, ADL scores, cognitive status, or gait (table 1). At the conclusion of the study, 115 participants had returned for their annual clinical examination. Of those, 2 participants converted from CDR 0 to 0.5 (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the samplea

The 125 participants had a total of 154 falls over the 365-day monitoring period; 75 individuals had at least one fall over a follow-up period ranging from 0 to 365 days (x̄ = 212 days). The number of falls ranged from 0 to 12 with 36 of the 75 fallers reporting only one fall. Of the 73 participants who completed a telephone interview about their first fall, 14 reported seeking medical attention. No one reported hospitalization. The majority of the falls occurred in the community during walking. There were no differences between the groups regarding the nature or location of the falls.

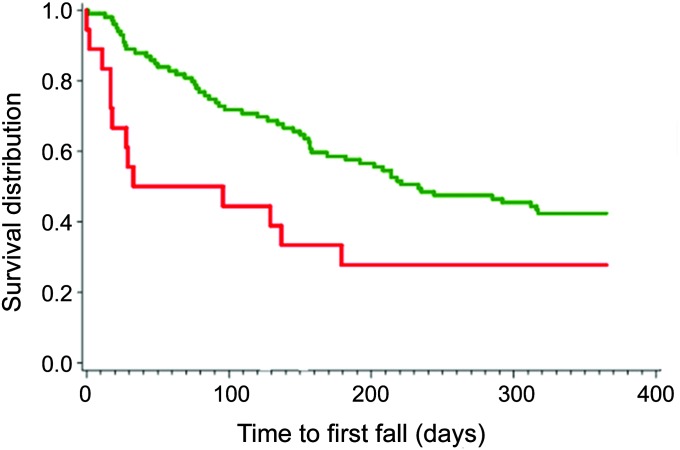

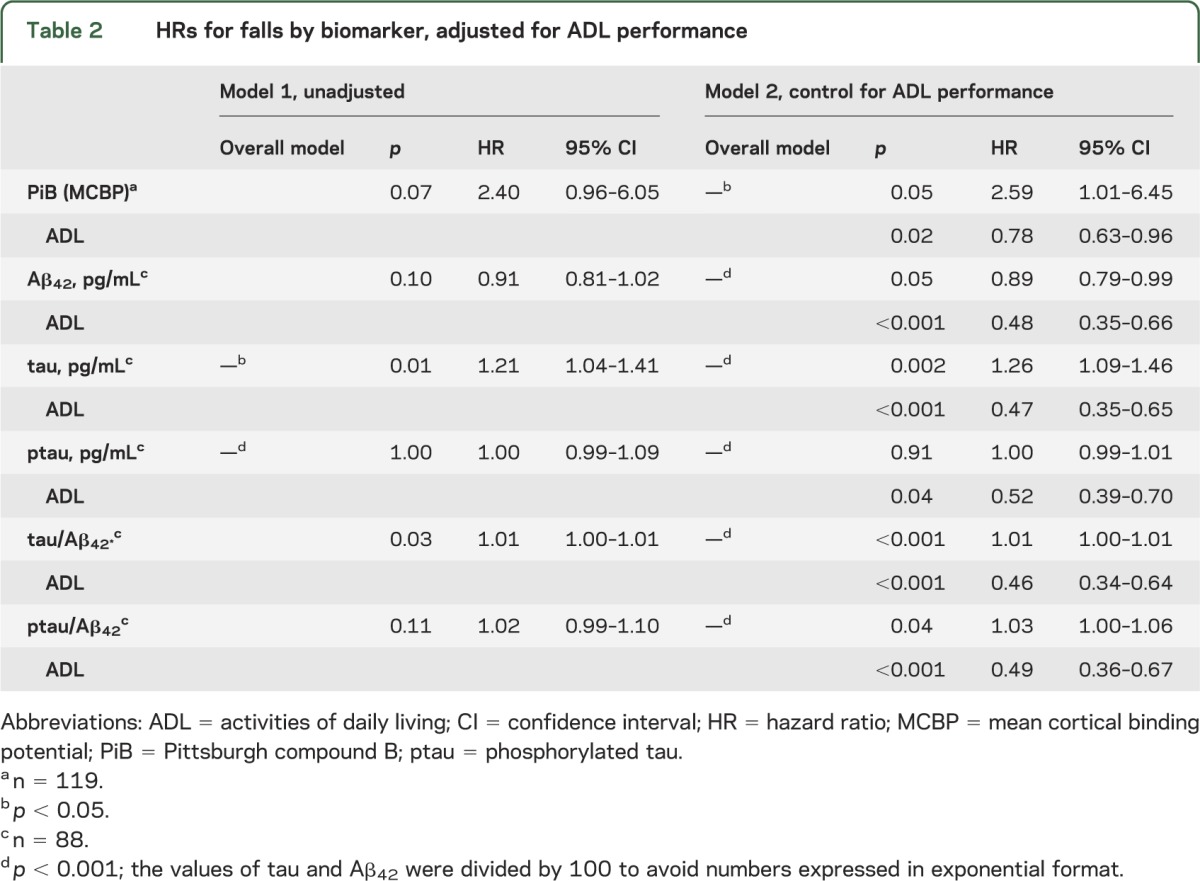

Seventy-five percent of participants in the high PiB uptake group (n = 18) and 60% of participants in the low PiB uptake group (n = 101) had at least one fall. The adjusted cumulative incidence of first fall was increased in the high PiB group when controlled for ADL performance (hazard ratio 2.95, 95% confidence interval 1.01–6.45, p = 0.05). In the adjusted model, the risk of falls is increased indicating ADL performance was a negative confounder. Likewise, the time to fall was significantly different for each CSF biomarker when adjusted for ADL performance (table 2). Kaplan-Meier curves for the high PiB uptake and healthy control groups are presented in figure 2.

Table 2.

HRs for falls by biomarker, adjusted for ADL performance

Figure 2. Time to first fall for participants with high and low PiB uptake.

Kaplan-Meier curve per PiB status. Red curves represent participants with high PiB status; green curves represent participants with low PiB status. PiB = Pittsburgh compound B.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is the increased risk of experiencing a fall among older adults with preclinical AD as detected using PiB PET imaging and CSF biomarkers. In unadjusted analyses, the faster time to first fall was also associated with ratios of CSF biomarkers and individual levels of tau, but not with individual levels of CSF Aβ42 or ptau. After adjustment for age and ADL performance, only the individual level of ptau was not related with time to first fall.

There is evidence to suggest that gait disorders are associated with or predict decline in cognitive function.34,35 The pathobiological mechanisms associated with preclinical AD and falls are unknown but the phenomenon of motor changes preceding cognitive changes is consistent with other studies of mobility problems experienced among persons with very early clinical signs of AD34 or mild cognitive impairment.34,35 Our findings extend the results of these studies to suggest that higher rates of falls may occur among persons early in the disease process, even before cognitive impairment. Viewed in context of other studies that examine the relationship between movement or falls and cognition, these findings provide new evidence of the link between falls and future cognitive decline.

Although it may be possible in the future to predict the development of AD dementia based on individual profiles of clinical data, neuroimaging studies, and CSF biomarkers, how the cascade of pathophysiologic changes may relate to the onset of clinical manifestation is not currently established.8 A better understanding of the mechanism of these falls and where they occur in the development of the disease may help with future diagnosis. This study supports the existence of a preclinical phase of AD and adds new information about the potential broad systemic changes that may be occurring in addition to protein deposition in the brain.13

The advantages of this study include a well-characterized sample of older adults and the high level of compliance among study participants. One limitation of the current study is the homogeneous nature of the sample. This sample of older adults was primarily white and well educated. In the general population of older adults, falls are more prevalent among white people compared to minorities and among those with higher education compared to those with lesser education.36 The fall rate in the healthy controls (60%) was higher than expected in the general population (33%),37 which may be attributed to demographic characteristics of the sample. In addition, other forms of pathology may have been present (e.g., brain small-vessel disease), which may have increased the risk of falls. These important covariates should be controlled in future studies.

Another possible limitation of the study is the use of self-reported measures of fall. Although all participants were judged to be cognitively normal (CDR 0) and fall ascertainment methods were intensive, underreporting of falls cannot be ruled out. However, strategies were used to aid in the recall of fall events and underreporting falls is more likely with recurrent falls.38 Our sample reported a greater than expected rate of falls. It is unknown whether our enhanced surveillance methods or characteristics of the sample resulted in increased reported falls.

Despite limitations, this study points to the importance of understanding not only the cognitive impairments associated with AD, but also the motor changes that appear to precede cognitive changes. Additional research is needed to assess the extent of fall risk among healthy older adults with preclinical AD and to begin to explore the mechanism causing falls differentially in these groups. Continued study of this phenomenon could provide a better understanding of the clinical presentation of preclinical AD and an underlying mechanism of the cause of falls.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge Judy Smith, PhD, Goldfarb School of Nursing; Lyn Byun, MSOT, Washington University School of Medicine; and Jane Works-Conte, MED, Washington University, for their assistance in collecting fall data. The authors are grateful for the reviewer's comments and helpful suggestions. The authors thank Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan for their generous support and the study participants for their dedication.

GLOSSARY

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- ADL

activities of daily living

- BP

binding potential

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- LP

lumbar puncture

- MCBP

mean cortical binding potential

- PiB

Pittsburgh compound B

- ptau

phosphorylated tau

- ROI

region of interest

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Susan Stark: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision or coordination, obtaining funding. Catherine Roe: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, analysis or interpretation of data, statistical analysis. Elizabeth Grant: acquisition of data, statistical analysis. Holly Hollingsworth: statistical analysis. Tammie Benzinger, Anne Fagan, and Virginia Buckles: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, study concept or design, acquisition of data, obtaining funding. John Morris: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, obtaining funding.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by NIH Alzheimer's Disease Research Center P50AG005681; Healthy Aging Senile Dementia P01AG003991; Antecedent Biomarkers for AD: The Adult Children Study P01AG026276; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Center Core for Brain Imaging P30NS04805609; and generous support from Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan.

DISCLOSURE

S. Stark is funded by NIH grant NIA P50 AG05681-27, HUD grant MOLHH0196-09, and CDC grant 1K01DD00033301, and received research support from The Retirement Research Foundation and the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation. C. Roe, E. Grant, and H. Hollingsworth report no disclosures. T. Benzinger has current research funding from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and has previously served on an advisory board for Eli Lilly. A. Fagan reports consulting for Eli Lilly and Company and Roche. V. Buckles reports no disclosures. J. Morris reports that neither he nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Morris has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by Janssen Immunotherapy and Pfizer. Dr. Morris has served as a consultant for Eisai, Esteve, Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Program, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer. He receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, and U19AG032438. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1279–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchner DM, Larson EB. Falls and fractures in patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. JAMA 1987;257:1492–1495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer's dementia. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silbert L, Dodge H, Lhana D, et al. In home continuous monitoring of gait speed: a sensitive method for detecting motor slowing associated with smaller brain volumes and dementia risk [abstract]. Presented at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference; July 2012; Vancouver

- 5.Mielke M, Savica R, Drubach D, et al. Slow gait predicts cognitive decline: a population based cohort study [abstract]. Presented at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference; July 2012; Vancouver

- 6.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JC, Selkoe DJ. Recommendations for the incorporation of biomarkers into Alzheimer clinical trials: an overview. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32:S1–S3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:280–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid (42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol 2007;64:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, et al. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2009;66:1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:795–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DK, Wilkins CH, Morris JC. Accelerated weight loss may precede diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1312–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Nontraditional risk factors combine to predict Alzheimer disease and dementia. Neurology 2011;77:227–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camicioli R, Howieson D, Oken B, Sexton G, Kaye J. Motor slowing precedes cognitive impairment in the oldest old. Neurology 1998;50:1496–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzpatrick AL, Buchanan CK, Nahin RL, et al. Associations of gait speed and other measures of physical function with cognition in a healthy cohort of elderly persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62:1244–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh compound-B. Ann Neurol 2004;55:306–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schafer K, et al. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies. Neurology 1997;48:1508–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer disease centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson DK, Storandt M, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Longitudinal study of the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1254–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wechsler D, Stone C. Manual: Wechsler Memory Scale. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grober E, Lipton R, Hall C, Crystal H. Memory impairment on free and cued selective reminding predicts dementia. Neurology 2000;54:827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler D. Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1955 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodglass H, Kaplan E. Boston Naming Test Scoring Booklet. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thurstone L, Thurstone L. Examiner Manual for the SRA Primary Mental Abilities Test. Chicago: Science Research Associates; 1949 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armitage S. An analysis of certain psychological tests used in the evaluation of brain injury. Psychol Monogr 1946;60:1–48 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mintun MA, LaRossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006;67:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996;16:834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blow F. Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test—Geriatric Version (MAST-G). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Alcohol Research Center; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults: the Duke Older Americans Resources and Services procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) adult questions [online]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/quest_data_related_1997_forward.htm#2009_NHIS. Accessed December 12, 2012

- 33.Lamb SE, Jorstand-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1618–1622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander NB, Hausdorff JM. Guest editorial: linking thinking, walking, and falling. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:1325–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu-Ambrose TY, Ashe MC, Graf P, Beattie BL, Khan KM. Increased risk of falling in older community-dwelling women with mild cognitive impairment. Phys Ther 2008;88:1482–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanlon JT, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum GG, Studenski S. Falls in African American and white community-dwelling elderly residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M473–M478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tinetti ME. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2003;348:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming J, Matthews FE, Brayne C. Falls in advanced old age: recalled falls and prospective follow-up of over-90-year-olds in the Cambridge City over-75s Cohort Study. BMC Geriatr 2008;8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]