Abstract

Targeting the adaptor protein (transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-activated protein kinase 1 (TAK1)-binding protein 1) (TAB1)-mediated non-canonical activation of p38α to limit ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury after an acute myocardial infarction seems to be attractive since TAB1/p38α interaction occurs specifically in very limited circumstances and possesses unique structural basis. However, so far no TAB1/p38α interaction inhibitor has been reported due to the limited knowledge about the interfaces. In this study, we sought to identify key amino acids essential for the unique mode of interaction with computer-guided molecular simulations and molecular docking. After validation of the predicted three-dimensional (3-D) structure of TAB1/p38α complex, we designed several peptides and evaluated whether they could block TAB1/p38α interaction with selectivity. We found that a cell-permeable peptide worked as a selective TAB1/p38α interaction inhibitor and decreased myocardial I/R injury. To our knowledge, this is the first TAB1/p38α interaction inhibitor.

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction is usually caused by coronary thrombosis that leads to critical tissue ischemia. Although coronary reperfusion is essential for myocardial salvage, it may at first exacerbate cellular damage sustained during the ischemic period. The corresponding adverse consequences are known as reperfusion injury.1,2 Despite years of studies, few intervention strategies and drugs are available to limit myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury.1,2

Multiple adverse events such as oxidative stress and intracellular calcium overload occur following myocardial I/R and contribute to cardiomyocyte death.1,2 Among the various intracellular signaling pathways activated during this process, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) seems to play a causative role in myocardial injury and dysfunction following I/R.3,4 The underlying mechanism(s) through which p38 activation contributes to I/R injury remain elusive but definitely involve apoptosis.3,4 p38α is the predominant isoform of p38 MAPK in the mammalian heart. It has been demonstrated that the activation of p38 MAPK during myocardial I/R primarily reflects p38α activation, which mediates injury.3,4 p38α activation during myocardial I/R results from its physical interaction with the adaptor protein transforming growth factor- (TGF-β)-activated protein kinase 1 (TAK1)-binding protein 1 (TAB1), but independent of the MAPK kinases (MKKs), namely MKK3 and MKK6.5,6,7,8,9 TAB1 can directly interact with p38α, but not with other p38 isoforms, in very limited circumstances, leading to phosphorylation at Thr180 and Tyr182 and subsequent activation of p38α with yet unclear mechanisms.4,10,11 These facts make TAB1/p38α interaction a very attractive target to limit myocardial I/R injury. The unique structural basis of TAB1/p38α interaction makes a prerequisite for the design of selective inhibitors. Circumstance specificity means that targeting TAB1/p38α interaction would potentially avoid disturbing the homeostatic function of p38α.4,11

The design of selective inhibitors to disrupt TAB1/p38α interaction depends on the elucidation of its structural basis. By comparison of the amino acid sequences of different p38 isoforms, the unique amino acids of p38α have been characterized with site-directed mutagenesis. Consequently, Thr218 and Ile275 of p38α have been demonstrated to be essential for the unique mode of TAB1/p38α interaction, but dispensable for the interaction between p38α and MKK3/6.12 However, due to the lack of the precise three-dimensional (3-D) structure of TAB1/p38α complex, it remains unclear whether there are other key amino acids in p38α essential for the unique mode of interaction. Furthermore, the corresponding key sites in TAB1 are still unknown. In this scenario, we sought to resolve these problems with computer-guided molecular simulations and molecular docking since such techniques have been successfully used in the study of protein–protein interfaces.13 In combination with sophisticated experimental techniques, we have identified the key sites essential for the unique mode of TAB1/p38α interaction. Moreover, we have established a cell-penetrating peptide which selectively blocks TAB1/p38α interaction.

Results

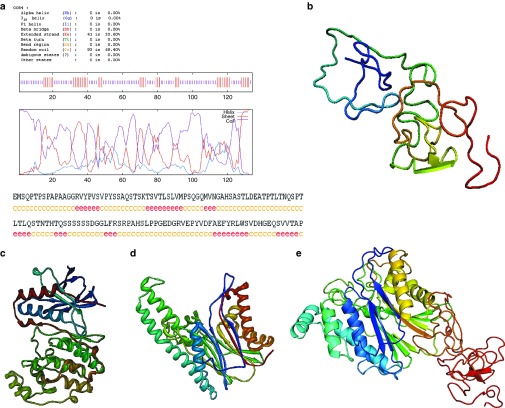

Molecular modeling of the 3-D structures of p38α and TAB1

Due to the poor sequence similarity of the C-terminal domain of human TAB1 (residues from 371 to 450, TAB1ΔN) to the known 3-D protein structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank, we first set out to construct the 3-D structure of TAB1ΔN using ab initio modeling method.14,15 Briefly, the secondary structure of TAB1ΔN was predicted using GOR (Garnier J, Osguthorpe DJ, and Robson B) IV method,16 which showed that 93 residues inclined to the random coil, whereas the other 41 residues exhibited a tendency to the extended strand (Figure 1a). The 3-D structure of TAB1ΔN was then obtained through considering the common bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles of the residues and through limiting the torsion angles (ϕ, ψ) of the residues due to the interactions of the side chains with its backbone with Ramachandran map.17 Further, minimizations were performed with Discover program under consistent valence force field (CVFF) and Charmm force field by using 40,000 steps of steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient minimization, until the gradient was <0.418 kJ/mol·Å. Finally, a 1,000 ps dynamics simulation was performed at 298 K to search the steady conformation. To account for the solvent effect, 5 Å water layer was added to the whole protein. The output conformers were collected at every 10 ps and totally 100 conformers were saved in the archive file. The optimal 3-D modeling structure of TAB1ΔN was chosen based on the low total energy and the priority suggested by profile_3D program (Figure 1b). Second, the crystal structures of human p38α and the N-terminal domain of human TAB1 (the residues from 1 to 370, TAB1ΔC) were extracted from Protein Data Bank (the entry codes are 1p38 and 2j4o, respectively) and used as templates. Under CVFF and Charmm force field, the hydrogen atoms were added. These structures were energy-minimized using Discover program followed by structural optimization using molecular dynamics calculations as stated above (Figure 1c,d). The heavy atom root-mean-square deviation values for p38α and TAB1ΔC were 2.3 and 3.4 Å, respectively. Thus, the molecular simulations were credible. Then the orientations of the COO− of TAB1ΔC and the NH4+ of TAB1ΔN were determined and the 3-D structure of full-length TAB1 was constructed. Under CVFF and AMBER force field, minimizations were performed, which was followed by structural optimization (Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

Molecular modeling of the three-dimensional (3-D) ribbon structures of human p38α and human TAB1 in the solvent. (a) The predicted secondary structure of TAB1ΔN with GOR IV method. (b) The optimized 3-D structure of TAB1ΔN based on ab initio modeling method. (c,d) The optimized 3-D structures of (c) p38α and (d) TAB1ΔC under CVFF and Charmm force field. (e) The optimized 3-D structure of full length TAB1 under CVFF and AMBER force field.

Molecular modeling of the 3-D TAB1/p38α complex structure

Because the surface electrostatic property is an important factor in the protein–protein interaction, the surface electrostatic potential distribution of TAB1 and p38α was analyzed with DELPHI program (Figure 2a,b). The 3-D rigid complex structure of TAB1 and p38α was then constructed with molecular docking.18,19 Among the candidates for the TAB1/p38α complex structure, the one with p38α Thr218 in the interfaces was chosen. The selected complex structure was energy-minimized using Discover program followed by structural optimization using molecular dynamics calculations as stated above (Figure 2c). It seemed that both hydrophobic interaction (Figure 2d) and electrostatic effect (Figure 2e) are involved in the binding. Based on the intermolecular hydrogen bond, distance geometry, and Van der Waals interaction mode, the binding sites between TAB1 and p38α were predicted and the key residues essential for the unique mode of interaction were determined. The predicted model suggests that Ile275 of p38α does not locate in the interfaces. However, it collaborates with Thr218 to maintain the unique local conformation of the protein. Consequently, even though Asn230 and Tyr258 of p38α are not unique amino acids, they constitute a unique interface together with Thr218 (Figure 2f). According to the predicted model, (i) Thr218 seems to form Van der Waals interaction with Ser399 and Ser401 of TAB1. Mutation of Thr218 to the corresponding residue (Gln218) in p38β, the closest homologue of p38α, should abolish TAB1/p38α interaction. (ii) Asp230, as the intermolecular hydrogen bond acceptor, seems to form two hydrogen bonds with Asn436 and Thr440 of TAB1. However, the big volume and the acid property of Asp230 seem to affect the binding activity. If the residue is replaced with Ala, the decreased volume and the neutral property should result in augmented binding activity. (iii) Tyr258 seems to anchor Ser399 and Asn436 of TAB1 via polar and π–π interactions. Mutation of Tyr258 to Ala should lead to reduced binding activity.

Figure 2.

The three-dimensional (3-D) modeling structure of TAB1/p38α complex. (a,b) The calculated surface electrostatic potential distribution of (a) p38α and (b) TAB1 based on DELPHI program. The red, blue, and white regions denote the negative electrostatic potential, the positive electrostatic potential, and the neutral electrostatic potential, respectively. (c–e) The predicted 3-D structure of TAB1/p38α complex (as shown in c). In this model, both (d) hydrophobic interaction and (e) electrostatic effect are involved in the binding. The red line denotes the main-chain carbon atom orientation of TAB1, and the green line denotes that of p38α. (f) The predicated key sites in the unique mode of TAB1/p38α interaction. The red line denotes the main-chain carbon atom orientation of TAB1, and the purple line denotes that of p38α.

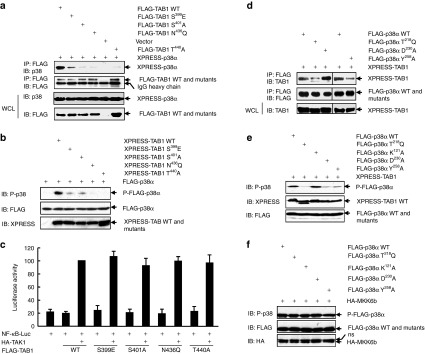

Validation of the predicted key sites involved in the unique mode of interaction

TAB1 and p38α co-overexpression leads to the interaction between exogenous TAB1 and exogenous p38α without disturbing the upstream kinases and other signaling pathways.10,12 Because such a strategy has been successfully used to identify Thr218 and Ile275 of p38α as key sites for the unique mode of TAB1/p38α interaction,10,12 we cotransfected 293T cells with a mammalian expression vector encoding tagged wild-type (WT) p38α or p38α mutants and a mammalian expression vector encoding tagged-TAB1 WT or mutants to analyze how the key sites might affect the binding activity. Co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that the interaction between exogenous TAB1 and exogenous p38α significantly decreased upon S399E, S401A, N436Q, or T440A mutation of TAB1, matching the prediction of modeling (Figure 3a). Consistently, the four TAB1 mutants led to sharply decreased levels of phosphorylation of co-overexpressed p38α as compared with TAB1 WT (Figure 3b). Whether the inability of these TAB1 mutants to interact with co-overexpressed p38α is caused by potential changes in the global structures of the proteins was then checked by analyzing their ability to facilitate TAK1 activation. It has been well established that co-overexpression of TAB1 with TAK1, but not overexpression of TAB1 alone, in mammalian cells leads to TAK1 activation, which consequently activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB).20 We co-expressed the NF-κB promoter-driven luciferase reporter with TAK1 and TAB1 WT or various mutants. The results showed that co-overexpression of TAB1 WT or mutants with TAK1 exhibited no significant differences in promoting NF-κB activation whereas overexpression of TAB1 WT or mutants alone did not lead to NF-κB activation (Figure 3c). Thus, these sites are specific for TAB1 to bind with p38α. As for TAB1 mutants, co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that the interaction between exogenous TAB1 and exogenous p38α decreased upon T218Q or Y258A mutation of p38α, but increased upon D230A mutation (Figure 3d). These data are consistent with the computational modeling. Then we analyzed TAB1 co-overexpression–dependent phosphorylation of these p38α mutants. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that the phosphorylation of p38α T218Q or Y258A under the condition of co-overexpression with TAB1 stepped down sharply as compared with p38α WT (Figure 3e). Interestingly, the phosphorylation of p38α D230A also decreased dramatically, suggesting only the most appropriate binding of TAB1 and p38α leads to optimal p38α phosphorylation (Figure 3e). Besides, mutation of an irrelevant site K121 showed no effect on p38α phosphorylation under the condition of co-overexpression with TAB1 (Figure 3e), suggesting that only mutation of the key sites essential for the unique mode of TAB1/p38α interaction hinders the consequent p38α phosphorylation. Moreover, the reduced phosphorylation of the p38α mutants T218Q, Y258A, and D230A under the condition of co-overexpression with TAB1 is not caused by potential changes in the global structures of the proteins because MKK6 co-overexpression–dependent phosphorylation was comparable between p38α WT and various mutants (Figure 3f). Taken together, these data suggest that the predicted complex structure is reasonable.

Figure 3.

Ser399, Ser401, Asn436, and Thr440 in TAB1 as well as Thr218, Asp230, and Tyr258 in p38α are critical to the unique mode of interaction. (a,b) 293T cells were cotransfected with tagged-p38α and tagged-TAB1 wild-type (WT) or TAB1 mutants. (a) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of cell lysates with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody was followed by immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-p38 antibody. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S3a. (b) How the mutation might affect TAB1 co-overexpression–dependent p38α phosphorylation was analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S3b. (c) 293T cells were cotransfected with the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) reporter pNF-κB-Luc, the control reporter pRL-TK, HA-TAK1, and FLAG-tagged TAB1 WT or TAB1 mutants. Luciferase activity was measured 36 hours after transfection. (d,e) 293T cells were cotransfected with XPRESS-TAB1 and FLAG-tagged p38α WT or p38α mutants. (d) IP of cell lysates with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody was followed by IB with an anti-TAB1 antibody. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S3c. (e) How the mutation might affect TAB1 co-overexpression–dependent p38α phosphorylation was analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S3d. (f) 293T cells were cotransfected with HA-MKK6b and FLAG-tagged p38α WT or p38α mutants. The phosphorylation of FLAG-p38α and expression of HA-MKK6b and FLAG-p38α were analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S3e. ns, not specific.

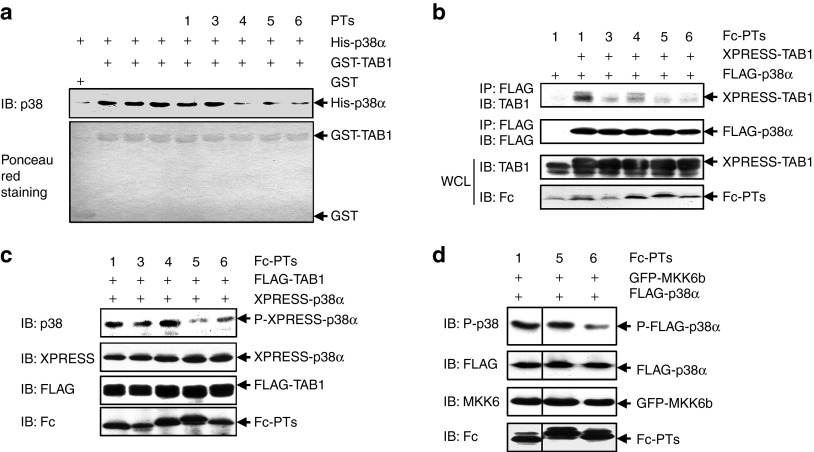

Design and characterization of candidate peptides potentially blocking TAB1/p38α interaction

Based on the previous report12 and the data above, five peptides were designed and chemically synthesized to disrupt TAB1/p38α interaction. Peptide PT2 was supposed to target the hydrophobic docking groove in p38α peptides PT3 and PT4 were supposed to bind with Ile275 and its surrounding unique residues since the maintenance of the unique local conformation is vital for the unique mode of interaction; peptide PT5 was expected to bind with the unique interface including Thr218; peptide PT6 should interfere with both the hydrophobic docking groove and the unique interface; whereas peptide PT1 was supposed to work as the control peptide (Supplementary Figure S1). The ability of chemically synthesized peptides to interfere with the interaction between Escherichia coli (E. coli)-derived TAB1 and E. coli-derived p38α was first analyzed except PT2 because of its poor solubility. GST (glutathione S-transferase)-pull down assays revealed that chemically synthesized PT4, PT5, and PT6 significantly suppressed TAB1/p38α interaction whereas PT1 and PT3 showed no effect (Figure 4a). To examine whether PT4, PT5, PT6, as well as PT2 could block TAB1/p38α interaction in cells, we cloned the peptides into a mammalian expression vector in frame with sequence encoding a pentadecapeptide linker (Gly4-Ser)3, followed by the Fc portion of a human IgG1. These chimeric genes directed the expression of recombinant fusion protein Fc-PTs. Co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that the interaction between co-overexpressed TAB1 and p38α was significantly inhibited by Fc-fused PT2, PT4, PT5, and PT6, as compared with Fc-PT1 (Figure 4b). With Fc-PT1 as control, immunoblotting analysis revealed that Fc-PT5 and Fc-PT6, but not Fc-PT2 and Fc-PT4, significantly suppressed TAB1 co-overexpression–dependent p38α phosphorylation (Figure 4c). We further analyzed whether Fc-PT5 and Fc-PT6 have some selectivity. With Fc-PT1 as control, immunoblotting analysis revealed that Fc-PT6, but not Fc-PT5, inhibited MKK6 co-overexpression–induced p38α phosphorylation (Figure 4d). Taken together, these data suggest that PT5, but not other designed peptides, might work as a selective inhibitor of TAB1/p38α interaction.

Figure 4.

Design and validation of candidate peptides potentially blocking the interaction. (a) Glutathione-Sepharose beads bound with Escherichia coli (E. coli)-derived GST-TAB1 or GST were incubated with E. coli-derived His-p38α in the presence or absence of chemically synthesized peptides (final concentration: 2 μmol/l). After washing the beads, the bound proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting (IB) analysis. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S4a. (b,c) 293T cells were cotransfected with tagged-TAB1, tagged-p38α, and a vector encoding various peptides in fusion with the Fc portion of a human IgG1. (b) Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody was followed by IB with an anti-TAB1 antibody. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S4b. (c) How the peptides might affect TAB1 co-overexpression–dependent p38α phosphorylation was analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S4c. (d) 293T cells were cotransfected with GFP-MKK6b, FLAG-p38α, and a vector encoding various peptides in fusion with the Fc portion of a human IgG1. How the peptides might affect MKK6 co-overexpression–dependent p38 phosphorylation was analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S4d. GFP, green fluorescent protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

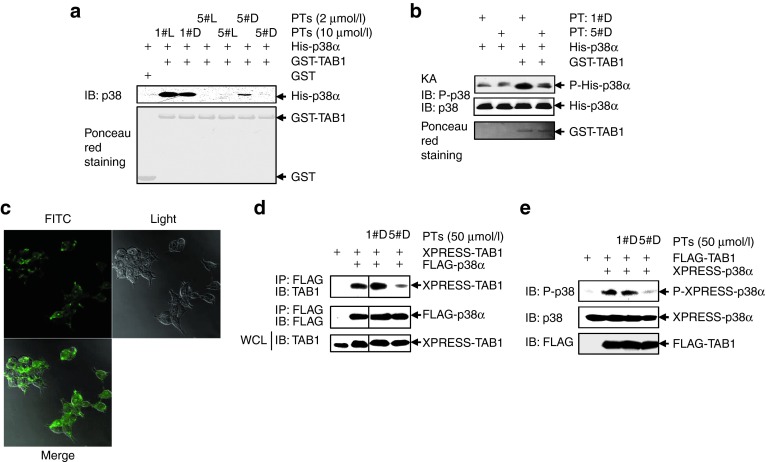

The cell-penetrating and protease-resistant form of peptide PT5 (5#D-PT) blocks co-overexpression–induced TAB1/p38α interaction

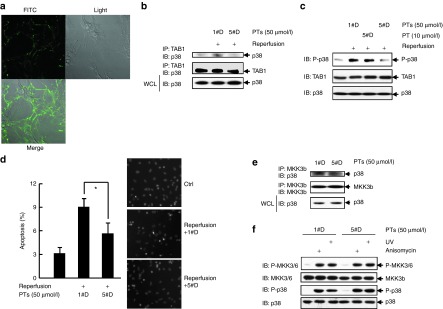

To evaluate how PT5 might affect TAB1/p38α interaction and p38α phosphorylation in a more physiological/pathological setting, we have to use cell-penetrating form of the peptide. The cell permeability was obtained by linking the 10-amino acid HIV TAT (48–57) transporter sequence to the C-terminal of the peptide. In addition, we synthesized not only the l-form (the physiological form, 5#L-PT) of the peptide but also the protease-resistant all-D-retroinverso form (5#D-PT) to expand its half-life in vivo. A successful example of such strategy is D-JNKI-1, a peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase.21 To compare the inhibitory effects of 5#L-PT and 5#D-PT on TAB1/ p38α interaction, GST-pull down assays with E. coli-derived TAB1 and E. coli-derived p38α were performed. As shown in Figure 5a, 2 μmol/l 5#D-PT was less potent to disrupt TAB1/p38α interaction than 2 μmol/l 5#L-PT. However, 10 μmol/l 5#D-PT completely blocked TAB1/p38α interaction. Moreover, in vitro protein kinase assays revealed that 10 μmol/l 5#D-PT blocked E. coli-derived TAB-mediated phosphorylation, but not basal phosphorylation, of E. coli-derived p38α (Figure 5b). To monitor peptide delivery, 5#D-PT was further conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Confocal microscopy revealed that FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT could be efficiently delivered into 293T cells (Figure 5c). A total of 50 μmol/l 5#D-PT significantly suppressed co-overexpression–induced TAB1/p38α interaction (Figure 5d) and p38α phosphorylation (Figure 5e) in 293T cells, whereas 50 μmol/l 1#D-PT exhibited little effects. Thus, 5#D-PT might be used as a cell-permeable inhibitor of TAB1/p38α interaction.

Figure 5.

The cell-penetrating and protease-resistant form of peptide PT5 (5#D-PT) blocks co-overexpression–induced TAB1/p38α interaction. (a) GST-pull down assays were performed as described in Figure 4a. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S5a. (b) Escherichia coli (E. coli)-derived His-p38α was incubated with or without E. coli-derived GST-TAB1 in the presence of 1#D-PT or 5#D-PT for 60 minutes at 30 °C in kinase buffer. A total of 20 μmol/l nonradioactive adenosine triphosphate was included to drive the kinase reaction. The samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S5b. (c) 293T cells were incubated with 50 μmol/l FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT for 30 minutes. The images were captured by confocal microscopy. (d,e) 293T cells were cotransfected with tagged-TAB1 and tagged-p38α. 1#D-PT or 5#D-PT was added into the medium 6 hours later. (d) Cell lysates were harvested 30 hours post-transfection. Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody was followed by IB with an anti-TAB1 antibody. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S5c. (e) How 5#D-PT might affect TAB1 co-overexpression–dependent p38α phosphorylation was analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S5d. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GST, glutathione S-transferase; KA, kinase assay; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

5#D-PT blocks the interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38α during simulated I/R with selectivity

Based on these observations, we sought to analyze whether 5#D-PT affects the interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38α. Typically, the interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38α occurs during myocardial I/R.5,6,7,8,9 Since all the key amino acids involved in the unique mode of interaction have their equivalents in rat TAB1 or rat p38a (Supplementary Figure S2), we employed a well established cell culture model of simulated I/R with rat cardiomyocytes. Confocal microscopy revealed that FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT could be efficiently delivered into cardiomyocytes (Figure 6a). Consistent with the previous reports,8 co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that simulated ischemia for 60 minutes followed by reperfusion for 10 minutes led to enhanced interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38 (Figure 6b), with p38α as the predominant isoform in cardiomyocytes.3,4 Addition of the cell-penetrating peptide 5#D-PT completely prevented the increase in the interaction (Figure 6b). TAB1/p38α interaction has been demonstrated to result in endogenous p38α phosphorylation and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes.5,6,7,8,9 As expected, 5#D-PT significantly inhibited endogenous p38 phosphorylation during simulated I/R (Figure 6c) and significantly reduced the number of apoptotic cells after simulated I/R (Figure 6d). On the other hand, 5#D-PT showed no inhibitory effect on the interaction of endogenous MKK3 and endogenous p38 in cardiomyocytes (Figure 6e). Moreover, 5#D-PT showed no inhibitory effect on the phosphorylation of endogenous p38 in cardiomyocytes in response to anisomycin and ultraviolet, two stimuli which significantly activated endogenous MKK3/6 (Figure 6f). Collectively, these data suggest that 5#D-PT blocks the interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38α during simulated ischemia and reperfusion with selectivity.

Figure 6.

5#D-PT blocks the interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38α during simulated I/R with selectivity. (a) Rat cardiomyocytes were incubated with 50 μmol/l FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT for 30 minutes. The images were captured by confocal microscopy. (b) Cardiomyocytes were cultured under normoxic conditions or exposed to 60 minutes of simulated ischemia followed by 10 minutes of reperfusion in the presence of 1#D-PT or 5#D-PT. After cell lysates were harvested, anti-TAB1 immunoprecipitation followed by anti-p38 MAPK immunoblotting was performed. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S6a. (c) Cardiomyocytes were treated as described as in b. After cell lysates were harvested, how 5#D-PT might affect endogenous TAB1-mediated endogenous p38α phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting (IB). Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S6b. (d) Cardiomyocytes were cultured under normoxic conditions or exposed to 60 minutes of simulated ischemia followed by 60 minutes of reperfusion in the presence of 1#D-PT or 5#D-PT. Apoptosis was quantified by Hoechst staining. Left, mean ± SD (n = 3), *P < 0.05; right, representative images. (e) Cardiomyocytes were cultured in the presence of 1#D-PT or 5#D-PT for 60 minutes. After cell lysates were harvested, anti-MKK3b immunoprecipitation followed by anti-p38 MAPK IB was performed. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S6c. (f) Cardiomyocytes were stimulated with or without 1 μg/ml anisomycin or 60 J/m2 ultraviolet and incubated for 20 minutes. Phosphorylation and expression of endogenous MKK3/6 and endogenous p38 were analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S6d. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion.

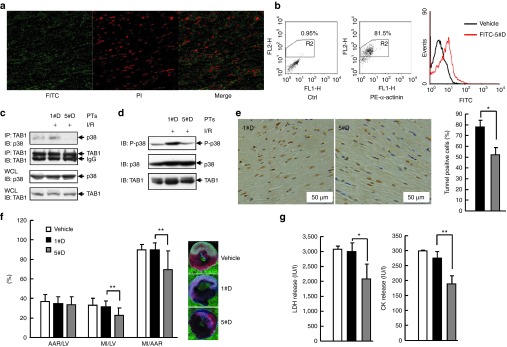

5#D-PT limits myocardial I/R injury in rats

To assess the in vivo relevance of the above findings, rat I/R model was established and FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT was administered by a single intravenous bolus injection 30 minutes before reperfusion. Transduction of FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT into rat heart tissue was confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure 7a) and by flow cytometry analysis of isolated primary rat cardiomyocytes (Figure 7b). Therefore, we used the same procedure to evaluate the effects of 5#D-PT on I/R-induced interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38a in vivo. Co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that I/R-induced interaction of endogenous TAB1 and endogenous p38 in vivo was impaired upon 5#D-PT administration (Figure 7c). TAB1/p38α interaction has been demonstrated to result in endogenous p38α phosphorylation and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes.5,6,7,8,9 As expected, I/R-induced endogenous p38 phosphorylation in vivo was blocked upon 5#D-PT administration (Figure 7d). Furthermore, 5#D-PT administration significantly reduced I/R-induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes in vivo (Figure 7e). Consequently, administration of 5#D-PT, but not 1#D-PT, 30 minutes before reperfusion led to reduced infarct size even though the area at risk was similar among vehicle-, 1#D-PT– and 5#D-PT–treated groups (Figure 7f). No differences existed in heart rate or temperature among the different groups (data not shown). The reduced infarct size was associated with decreased in vivo release of lactate dehydrogenase and creatine kinase, indicator of cardiomyocyte death (Figure 7g). Thus, in vivo administration of 5#D-PT protects myocardium from I/R damage, in keeping with the protective actions observed in cultured myocytes.

Figure 7.

5#D-PT reduces myocardial I/R injury in rats. (a,b) FITC-conjugated 5#D-PT (green) was administered by a single intravenous bolus injection 30 minutes before reperfusion. (a) Heart tissue was harvested 30 minutes after reperfusion and was cut in a cryomicrotome (−20 °C). After counterstained with propidium iodide (PI, red), tissue sections were subjected to confocal microscopy. (b) Adult primary cardiomyocytes were isolated 30 minutes after reperfusion and were subjected to intracellular staining with an antibody against α-actinin followed by flow cytometry analysis. α-Actinin+ cells were gated and histograms of FITC intensity were shown. (c) Rats were subjected to myocardial I/R or left untreated, proteins were isolated from heart tissue frozen 30 minutes after reperfusion. Then, anti-TAB1 immunoprecipitation followed by anti-p38 MAPK immunoblotting (IB) was performed. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S7a. (d) Rats were treated as described as in c. After cell lysates were harvested, how 5#D-PT might affect endogenous TAB1-mediated endogenous p38 phosphorylation in vivo was analyzed by IB. Densitometric readings were shown in Supplementary Figure S7b. (e) Apoptotic cardiomyocytes in the infarct border zone 24 hours after myocardial I/R was quantified by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay and hematoxylin staining. Left, representative images; right, mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. (f) Twenty-four hours after myocardial I/R, the left ventricle (LV) were dissected, then the area at risk (AAR) and myocardial infarct (MI) size were determined by Evans blue and 1% 2,3,5-triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride staining. Data from 9–16 mice per group are summarized. **P < 0.01. (g) Twenty-four hours after myocardial I/R, the LDH/CK levels in animal blood samples were determined. Data from 9–16 mice per group are summarized. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. CK, creatine kinase; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

Recent advances in computer hardware and software have led to the development of increasingly successful molecular simulations of protein structural dynamics and molecular docking.13 These advances have resulted in models that increasingly agree with experimental observations, providing new insights into biological mechanisms.13 Here, in combination with sophisticated experimental techniques, we have identified Asp230 and Tyr258, as well as Thr218, in p38α are critical for the specific interaction with TAB1, whereas the corresponding key sites in TAB1 were Ser399, Ser401, Asn436, and Thr440. Moreover, we have established a cell-penetrating peptide which selectively blocks the interaction between TAB1 and p38α and significantly limits myocardial I/R injury in vitro and in vivo.

It seems that the binding affinity does not correlate with the level of TAB1-mediated phosphorylation: even though D230A mutation in p38α resulted in increased binding activity, TAB1-dependent phosphorylation of p38α D230A decreased dramatically (Figure 3d,e). TAB1-mediated p38α phosphorylation likely represents autophosphorylation.10 It has been proposed that p38α undergoes conformational changes before autophosphorylation happens. Thus, it seems that the binding affinity might be very critical and subtle changes might interfere with the appropriate conformational changes and the optimal p38α autophosphorylation.22 Thus, only the optimal binding affinity (not higher or lower) leads to the optimal p38α autophosphorylation.

The above notion helps to explain how the cell-permeable peptide 5#D-PT binds to p38α without mimicking the effects of TAB1. Although 5#D-PT blocks TAB1/p38α interaction in vitro and in vivo, we were unable to detect its binding to p38α (data not shown). This is not a surprise, since the binding affinity of TAB1/p38α interaction was predicted to be −386.48 kJ/mol, whereas that of 5#D-PT/p38α interaction was predicted to be −152.83 kJ/mol, according to our computational modeling (data not shown). As 5#D-PT blocked E. coli-derived TAB-mediated phosphorylation, but not basal phosphorylation, of E. coli-derived p38α as revealed by in vitro protein kinase assays (Figure 5b), it seems that the abundant amount of 5#D-PT prevents TAB1 binding to p38α, but the low-binding affinity excludes the possibility of the peptide to mimic the effects of TAB1 binding (in terms of promoting p38α phosphorylation). Further studies are required to address this issue.

Our data further support the notion that targeting TAB1/p38α interaction is promising to limit I/R injury after an acute myocardial infarction. Apoptosis has been revealed as a mechanism through which p38 activation contributes to myocardial I/R injury.3,4 Indeed, 5#D-PT administration blocked I/R-induced endogenous p38 activation and reduced I/R-induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo (Figures 6 and 7). Therefore, this peptide inhibitor reduces infarct size through, at least partially, suppressing p38 activation and the consequent apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. The heart contains resident inflammatory/immune cells, extracellular matrix components, and fibroblasts as well as cardiomyocytes. Oxidative stress leads to the recruitment of more inflammatory/immune cells following myocardial I/R.1,2 TAB1/p38α interaction occurs in cardiomyocytes in response to myocardial I/R.3,4 Our data show that 5#D-PT can gain entry to cardiomyocytes (Figure 7a,b). However, this peptide inhibitor might also distribute into other types of cells in the heart. It remains unknown whether in vivo TAB1/p38α interaction happens in other types of cells in the heart during myocardial I/R. If it does happen, 5#D-PT might inhibit apoptosis of cardiomyocytes indirectly through targeting those cells. Moreover, the mechanisms underlying the in vivo protective role of this peptide inhibitor might be much more complicated than suppressing apoptosis of cardiomyocytes: in vivo p38 activation has been suggested to employ other mechanisms including enhancing oxidative stress and inflammation to augment myocardial injury.3,4,23 Because TAB1-mediated non-canonical activation of p38 in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes is not associated with the expression of proinflammatory genes,24 it is possible that in vivo I/R-induced p38 activation in cardiomyocytes augments oxidative stress and inflammation through crosstalk with other components in the heart. Another possibility is that in vivo I/R-induced p38 activation in cells other than cardiomyocytes in the heart augments oxidative stress and inflammation. Our present work cannot address these issues. The use of mouse models with conditional knockout of p38α in different types of cells in the heart might provide valuable clues.

Nevertheless, we have identified a peptide inhibitor which may have potential as a therapeutic to attenuate myocardial I/R injury. The maximal concentration of the peptide (molecular weight: 3,136.5) added to rats in vivo should be 32 μmol/l since the average plasma volume of a rat is about 10 ml.25 Thus, the peptide inhibitor may be more efficient in vivo than in vitro. Besides, it seems that amyloidogenic light chains induce cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction and apoptosis via a non-canonical p38α MAPK pathway.26 Thus this peptide may also have potential as a therapeutic to attenuate such cardiac dysfunction. At least, it can work as a tool to analyze the effects mediated by TAB1/p38α interaction under various circumstances including, but not restricted to, cardiac dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Animal handling. Animals were purchased from Institutes of Experimental Animals, Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Beijing, China) and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. All experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care.

Statistics analysis. The data were shown as mean ± SD. The Student's t-test was used to compare the difference between the two groups. The difference was considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Methods. Detailed methods are presented in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. The predicted models of the interaction between p38α and the designed peptides (PT2-6) with PT1 as control. Figure S2. Sequence alignment of hTAB1 versus rTAB1 or hp38α versus rp38α. Figure S3. Densitometric readings of Figure 3a,b,d–f. Figure S4. Densitometric readings of Figure 4b–d. Figure S5. Densitometric readings of Figure 5a,b,d,e. Figure S6. Densitometric readings of Figure 6b,c,e,f. Figure S7. Densitometric readings of Figure 7c,d. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Jianping Ren for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30973547, 31100544), Key Natural Science Program of Beijing (7101008), and National Key Basic Research Program of China (2010CB911904). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: a neglected therapeutic target. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:92–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI62874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion–from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denise Martin E, De Nicola GF, Marber MS. New therapeutic targets in cardiology: p38 alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase for ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2012;126:357–368. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marber MS, Rose B, Wang Y. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway–a potential target for intervention in infarction, hypertrophy, and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumphune S, Bassi R, Jacquet S, Sicard P, Clark JE, Verma S, et al. A chemical genetic approach reveals that p38alpha MAPK activation by diphosphorylation aggravates myocardial infarction and is prevented by the direct binding of SB203580. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2968–2975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno M, Bassi R, Gorog DA, Saurin AT, Jiang J, Heads RJ, et al. Diverse mechanisms of myocardial p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation: evidence for MKK-independent activation by a TAB1-associated mechanism contributing to injury during myocardial ischemia. Circ Res. 2003;93:254–261. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000083490.43943.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Miller EJ, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Russell RR, 3rd, Young LH. AMP-activated protein kinase activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase by increasing recruitment of p38 MAPK to TAB1 in the ischemic heart. Circ Res. 2005;97:872–879. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000187458.77026.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler B, Feil R, Hofmann F, Willenbockel C, Drexler H, Smolenski A, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I inhibits TAB1-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase apoptosis signaling in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32831–32840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota A, Zhang J, Ping P, Han J, Wang Y. Specific regulation of noncanonical p38alpha activation by Hsp90-Cdc37 chaperone complex in cardiomyocyte. Circ Res. 2010;106:1404–1412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge B, Gram H, Di Padova F, Huang B, New L, Ulevitch RJ, et al. MAPKK-independent activation of p38alpha mediated by TAB1-dependent autophosphorylation of p38alpha. Science. 2002;295:1291–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1067289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shen B, Lin A. Novel strategies for inhibition of the p38 MAPK pathway. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Zheng M, Chen J, Xie C, Kolatkar AR, Zarubin T, et al. Determinants that control the specific interactions between TAB1 and p38α. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3824–3834. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3824-3834.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JA, McClendon CL. Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces. Nature. 2007;450:1001–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature06526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F, Menziani C, Scheer A, Cotecchia S, De Benedetti PG. Ab initio modeling and molecular dynamics simulation of the alpha 1b-adrenergic receptor activation. Methods. 1998;14:302–317. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov S, Nikiforovich GV, Marshall GR. Ab initio modeling of small, medium, and large loops in proteins. Biopolymers. 2001;60:153–168. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:2<153::AID-BIP1010>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier J, Gibrat JF, Robson B. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence. Meth Enzymol. 1996;266:540–553. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran GN. Protein Structure and Crystallography. Science. 1963;141:288–291. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3577.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Li Y, Shen B. The design of antagonist peptide of hIL-6 based on the binding epitope of hIL-6 by computer-aided molecular modeling. Peptides. 2004;25:1123–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Han G, Feng J, Wang J, Wang R, Xu R, et al. Glutamic acid decarboxylase-derived epitopes with specific domains expand CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Lin SC, Huang Y, Kang YJ, Rich R, Lo YC, et al. XIAP induces NF-kappaB activation via the BIR1/TAB1 interaction and BIR1 dimerization. Mol Cell. 2007;26:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsello T, Clarke PG, Hirt L, Vercelli A, Repici M, Schorderet DF, et al. A peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase protects against excitotoxicity and cerebral ischemia. Nat Med. 2003;9:1180–1186. doi: 10.1038/nm911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin R, Lebendiker M, Engelberg D, Livnah O. Structures of p38alpha active mutants reveal conformational changes in L16 loop that induce autophosphorylation and activation. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sy JC, Seshadri G, Yang SC, Brown M, Oh T, Dikalov S, et al. Sustained release of a p38 inhibitor from non-inflammatory microspheres inhibits cardiac dysfunction. Nat Mater. 2008;7:863–868. doi: 10.1038/nmat2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Kang YJ, Han J, Herschman HR, Stefani E, Wang Y. TAB-1 modulates intracellular localization of p38 MAP kinase and downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6087–6095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton JC, Dark JM, Garland HO, Morgan MR, Pidgeon J, Soni S. Changes in water and electrolyte balance, plasma volume and composition during pregnancy in the rat. J Physiol (Lond) 1982;330:81–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Guan J, Jiang B, Brenner DA, Del Monte F, Ward JE, et al. Amyloidogenic light chains induce cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction and apoptosis via a non-canonical p38alpha MAPK pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4188–4193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912263107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.