Abstract

The high sensitivity of Fanconi’s anemia (FA) cells to drug induced DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICL) such as diepoxybutane (DEB) was used as a part of FA screening in the children with clinical suspicion of FA. The study considered a total of 66 children with the hematological and/or congenital phenotypic symptoms reminiscent of FA. Blood samples from patients with clinical suspicion of FA and controls were collected for chromosome fragility evaluation by the DEB test. According to the results of DEB test, the patients were divided into two subgroups: FA displaying typical DEB sensitive cellular response and non FA.

In this study, 10 out of 66 patients were found to have a FA cellular phenotype. The percentage of DEB-induced aberrant cells was increased more than 26 times in FA patients (range 22.00–82.00% with a mean of 48.32%) when compared to non FA patients (range 0.00–12.00% with a mean of 1.84%). The number of DEB-induced breaks/cells was more than 68 times higher in FA patients (range 0.26–4.39 with a mean of 1.37 breaks/cell) when compared to non FA patients (range 0.00–0.20 with a mean of 0.02 breaks/cell). The spontaneous chromosome fragility values in FA patients were overlapping those in non FA patients. Our results indicate that the DEB sensitivity test is the most reliable in vitro method for verification of the FA cellular phenotype.

Keywords: Chromosome fragility, Diepoxybutane (DEB), Fanconi’s anemia (FA)

INTRODUCTION

Fanconi’s anemia (MIM ID #227650) (FA) is a rare autosomal recessive and a rarely X-linked recessive chromosomal breakage disorder, found in 20 to 30% of children with inherited aplastic anemias (AA) [1,2]. The phenotypic heterogeneity of FA presents an appearance of peripheral pancytopenia, progressive bone marrow failure (BFM), developmental abnormalities, short stature and increased predisposition to cancer [2]. Fanconi’s anemia is a genetically heterogeneous disease, as 15 different FA complementary groups and corresponding genes have been currently identified [3–6]. The literature provides evidence that FA is an oxidative stress-related disease, defective for repair of oxidative DNA damage, confirming a direct link between reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, oxidative DNA damage and chromosomal breakages [7–10]. One of the main features of FA cells is an elevated incidence of spontaneous chromosomal aberrations, which could be further triggered by interstrand crosslinks (ICL) inducing agents such as diepoxybutane (DEB), mitomycin C (MMC), cis-platin and melphalan [11,12]. High sensitivity of FA cells to cytotoxic and clastogenic effects of ICL agents, provides a unique cellular marker that is used to distinguish FA from other BFM and chromosomal breakage syndromes [13]. In this study we used the DEB-induced chromosome fragility test for differential diagnosis of FA in Serbian children with clinical suspicion of FA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Samples

From February 2004 until March 2011, 66 children (41 boys and 25 girls, aged from one to 18 years) suspected of having FA were diagnosed and treated at the Mother and Child Health Care Institute of Serbia “Dr. Vukan Cupic” and the University Children’s Hospital, Belgrade, Serbia. These are the two largest pediatric hospitals in Serbia that cover about 80% of FA patients.

Blood samples from patients with clinical suspicion of FA and controls (healthy children of the same age as patients and other healthy individuals) were collected for chromosome fragility evaluation by the DEB test. Clinical data from patients with suspicion of FA were obtained from their clinicians, including age of onset of hematological disease and family screening results. According to the results of the DEB test, the patients were divided into two subgroups: FA displaying typical DEB sensitive cellular response and non FA.

The Diepoxybutane Test

The DEB sensitivity test on peripheral blood lymphocytes was performed using standard procedure [11,12,14] with minor modifications. Four blood cultures were prepared for each patient. Forty-eight hours after the culture set-up, two cultures were treated with DEB at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL [12], and the remaining cultures were left for spontaneous chromosome fragility evaluation. Cells were harvested 72 hours after initiation with the presence of colcemid during the last 2 hours (2.5 mg/mL). Staining with Giemsa solution was applied [12]. A total of 100 metaphase cells per subject were scored and analyzed for chromosome and chromatid aberrations, according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) [15]. Chromatid and chromosome breaks, and acentric fragments were scored as one break. Dicentric and ring chromosomes and radial figures were scored as two breaks [14,16]. Chromosome fragility evaluation parameters were: percentage of aberrant cells, number of breaks per cell and number of breaks per aberrant cell.

Statistical Analyses

In a discriminatory analysis, Chi square test was used to evaluate the significance of difference between examined cultures of patients [14] and healthy controls. The FA and non FA groups were distinguished by cut-off values forming ranges as previously described [16].

RESULTS

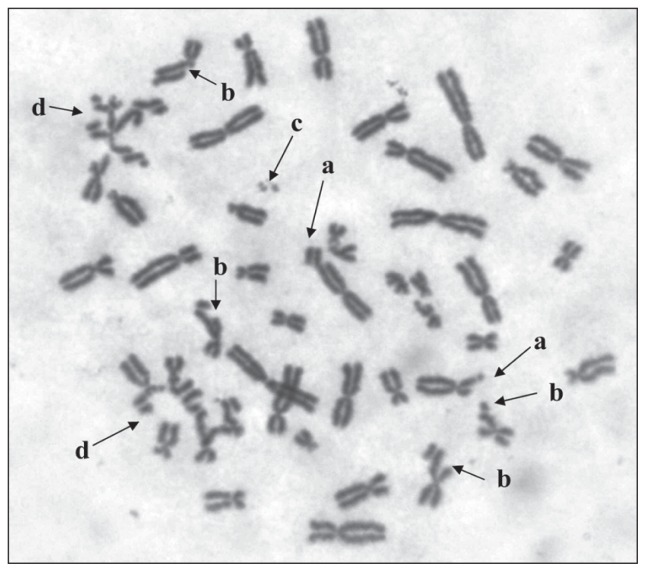

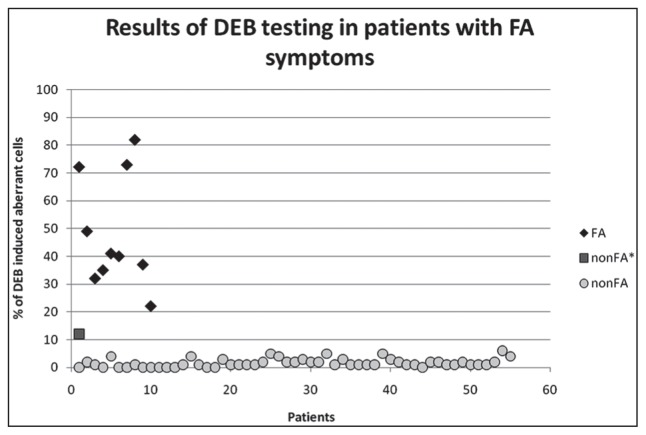

The chromosome fragility was evaluated by the DEB test in 66 patients with clinical suspicion of FA. The main criteria for the determination of chromosome fragility were as follows: percentage of aberrant cells, breaks/cell, breaks/aberrant cell. According to the results of the DEB test, the patients were divided into two subgroups: FA, displaying typical DEB sensitive cellular response, and non FA. A summary of the results obtained on spontaneous and DEB-induced fragility for both subgroups (FA and non FA) and controls are presented on Table 1. Ten (15.2%) out of 66 examined patients were found to have a FA cellular phenotype with increased number of DEB-induced chromatid and chromosome breaks and a variety of chromatid and chromosome interchanges (Figure 1, Table 2). The percentage of DEB-induced aberrant cells was increased more than 26 times in FA patients (range 22.00–82.00% with a mean of 48.32%) when compared to non FA patients (range 0.00–12.00% with a mean of 1.84%). Patient No. 8 reached the maximal percentage of DEB-induced aberrant cells of 82.00%, while the minimal value was 22.00% in patient No. 10 (Table 2). The number of DEB-induced breaks/cells was more than 68 times higher in FA patients (range 0.26–4.39 with a mean of 1.37 breaks/cell) when compared to non FA patients (range 0.00–0.20 with a mean of 0.02 breaks/cells) (Table 1). Patient No. 8. displayed the maximal value of 4.39 breaks/cell and FA patient No. 10 reached the minimal value of 0.26 breaks/cell. Statistical analysis showed significant difference between FA and non FA groups (Mann-Whitney test: p <0.0001) and no overlapping (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Evaluation of spontaneous and diepoxybutane-induced chromosome fragility findings in Fanconi’s anemia and non Fanconi’s anemia patient groups.

| Parameters | Group | n | Mean | Media | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Spontaneous Chromosome Fragility | Breaks/cell | FA | 10 | 0.12 | 0.075 | 0.13 | 0.00–0.39 |

| Non FA | 56 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00–0.07 | ||

| Control | 94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.007 | 0.00–0.03 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Aberrant cells (%) | FA | 10 | 9.30 | 6.50 | 9.01 | 0.00–29.00 | |

| Non FA | 56 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.00–7.00 | ||

| Control | 94 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.00–3.00 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Breaks/aberrant cell | FA | 10 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 0.42 | 0.00–1.50 | |

| Non FA | 56 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00–1.50 | ||

| Control | 94 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.00–1.50 | ||

|

| |||||||

| DEB-Induced Chromosome Fragility | Breaks/cell | FA | 10 | 1.37 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 0.26–4.39 |

| Non FA | 56 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00–0.20 | ||

| Control | 94 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00–0.17 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Aberrant cells (%) | FA | 10 | 48.32 | 40.50 | 20.28 | 22.00–82.00 | |

| Non FA | 56 | 1.84 | 1.00 | 2.04 | 0.00–12.00 | ||

| Control | 94 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.56 | 0.00–8.00 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Breaks/aberrant cell | FA | 10 | 2.50 | 2.43 | 1.24 | 1.18–5.35 | |

| Non FA | 56 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.00–2.67 | ||

| Control | 94 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.00–3.40 | ||

SD: Standard deviation. Differences between FA and non FA groups for the parameterizations of induced breakage: p <0.001.

Figure 1.

The DEB-induced chromosome aberrations in patient No. 8 with FA: (a) chromosome break, (b) chromatid break, (c) acentric fragment, (d) chromatid exchanges.

Table 2.

Spontaneous and diepoxybutane-induced chromosome fragility in 10 patients with Fanconi’s anemia.

| Spontaneous Chromosome Fragility | DEB-Induced Chromosome Fragility | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA Patient | Breaks/Cell | Aberrant Cells (%) | Breaks/Aberrant Cell | Breaks/Cell | Aberrant Cells (%) | Breaks/Aberrant Cell |

| 1 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.15 | 72.22 | 2.97 |

| 2 | 0.07 | 5.00 | 1.40 | 1.50 | 49.00 | 3.06 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 32.00 | 2.97 |

| 4 | 0.08 | 8.00 | 1.00 | 0.68 | 35.00 | 1.94 |

| 5 | 0.27 | 18.00 | 1.50 | 0.58 | 41.00 | 1.41 |

| 6 | 0.12 | 9.00 | 1.33 | 0.48 | 40.00 | 1.20 |

| 7 | 0.18 | 15.00 | 1.20 | 1.75 | 73.00 | 2.40 |

| 8 | 0.39 | 29.00 | 1.34 | 4.39 | 82.00 | 5.35 |

| 9 | 0.03 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 37.00 | 2.46 |

| 10 | 0.06 | 5.00 | 1.20 | 0.26 | 22.00 | 1.18 |

| Mean | 0.12 | 9.30 | 1.10 | 1.37 | 48.32 | 2.49 |

| SD | 0.12 | 9.01 | 0.42 | 1.22 | 20.28 | 1.24 |

Figure 2.

The DEB-induced chromosomal breakage in the FA and non FA groups of patients.

The spontaneous chromosome fragility(percentage of aberrant cells and breaks/cell)values in 10FA patients were overlapping those in non FA patients (Table 1). Nine out of 10 FA patients showed an increased rate of spontaneous breaks, while only one patient in this group (patient No. 3.) had no spontaneous breaks (Table 2). Thus, the mean percentage of spontaneous aberrant cells in the FA group was 9.30% (range 0.00–29.00%) and the mean value of spontaneous breaks/cells was 0.12 (range 0.00–0.39) (Table 1). In the non FA group of patients, the mean values of spontaneous breakages were 0.93% for percentage of aberrant cells (range 0.00–7.00%) and 0.01 for breaks/cell (range 0.00–0.06) (Table 1). Because of overlapping, these two groups could not be distinguished by the spontaneous breakage. Controls and the non FA group displayed similar values of spontaneous chromosome fragility with the mean percentage of aberrant cells 0.34% (range 0.00–3.00%) and the mean breaks/cell 0.00 (range 0.00–0.03) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Fanconi’s anemia is rare autosomal recessive disorder, characterized by a high clinical and genetic heterogeneity [14,16–21]. Diagnosis of FA on the basis of clinical features is often difficult and unreliable, due to the possible overlap of the FA phenotype with that of a variety of genetic and non genetic BFM syndromes [2,22]. Nowadays, chromosome fragility induced by ICL-inducing agents, such as DEB or MMC is the most widely used test for the diagnosis of FA. We report here the results of the DEB-induced chromosome fragility test as screening for FA in Serbian children with clinical suspicion of FA.

This study revealed 10 (15.2%) out of 66 examined patients to have a FA cellular phenotype with increased DEB-induced chromosome fragility. A lower incidence of FA in the cohort of 66 patients with pediatric AA when compared to published data (25–30%) [1], could not be the true frequency of FA in Serbian patients with pediatric AA, as there might be the chance of selection bias, assuming that not all of patients with AA underwent DEB testing.

In our study, the spontaneous chromosome fragility (percentage of aberrant cells and breaks/cell) values in 10 FA patients were overlapping those in non FA patients. The International Fanconi’s Anemia Registry (IFAR) study showed that the range of spontaneous chromosome breaks in FA group of 104 patients (0.02–1.90 breaks/cell with a mean of 0.27) was overlapping with the range found in a non FA group of 224 patients (0.00–0.12 breaks/cell with a mean of 0.02) [16]. In this study, the unreliability of base line of chromosome breakage in differential diagnosis of FA [16,22] was confirmed. Thus, baseline breakage frequency was proven not to be a useful method for discrimination of FA patients.

According to the DEB sensitivity test, the percentage of DEB-induced aberrant cells in the examined groups was increased more than 26 times in FA patients when compared to non FA patients. The number of DEB-induced breaks/cells was more than 68 times higher in FA patients when compared to non FA patients. There was a clear discrimination between FA and non FA subgroups with no overlapping. The IFAR study, also significantly differed the FA group from the non FA group on the basis of DEB-induced chromosome fragility. The percentage of induced aberrant cells in their study was 85.15% in FA patients and 5.12% in the non FA group [16]. Similarly, the mean of DEB-induced breaks/cell in FA patients was 8.96, while in the non FA group it was 0.06 [16]. These two groups showed no overlapping. Our results are in the line with IFAR report [16] and other similar studies [22–24] because FA and non FA groups could be distinguished by the percentage of DEB-induced aberrant cells (FA 22.00–82.00% vs. non FA 0.00–12.00%) and breaks/cell (FA 0.26–4.39 vs. non FA 0.00–0.20).

However, the level of variability in DEB-induced aberrant cells between the 10 patients with FA is very high with ranges from 22.00 to 82.00% (see Tables 1 and 2; Figure 2). Part of this high variability in the patients with FA is due to the existence of subgroup of patients who have lower values of chromosome fragility parameters (Table 2; borderline patients Nos. 3, 4 and 10). This subgroup corresponds to FA patients with T-cell mosaicism, who represent 15–25% of all FA patients [25–27]. Somatic mosaicism is produced when one of the pathogenic mutations is reverted in a hematopoietic precursor cell [27–29]. In previously published studies, FA patients with <40% of aberrant cells were considered mosaic, while those with a proportion between 40 and 60% were considered as possible mosaics; FA patients with proportion >60% of aberrant cells were considered as non mosaic patients with FA [30]. Similarly, in our study, all FA patients with <35 % of aberrant cells were considered mosaic (patients Nos. 1 and 3, −20%), while those with a proportion >60% of aberrant cells were considered non mosaic patients with FA, awaiting for additional evidence of mosaicism. However, the high level of variability of DEB-induced aberrant cells we found in the group of non FA patients, with range from 0.00 to 12.00%, due to the borderline DEB sensitivity of some patients. These patients might be considered mosaic FA or they represent non FA patients with higher sensitivity (up to 16%) to ICL agents due to an unknown genetic background [30].

Although high sensitivity to ICL-inducing agents is the hallmark of FA cells, an accurate diagnosis is compromised in some cases, especially in mosaic patients. Recently, Castella et al.[30] proposed a new chromosome fragility index that provides a clear cut-off diagnostic level unambiguously distinguishing patients with FA, including mosaic from non FA individuals, which should be improved in the near future. However, molecular investigation and identification of the FA complementary group for each DEB sensitive FA patient is the next step necessary in establishing the diagnosis of FA, its therapy management and genetic counseling of affected families.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of Serbia (Grant No. 173046).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter BP. Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. In: Handin RI, Stossel TP, Lux SE, editors. Blood: Principles and Practice of Hematology. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1995. pp. 227–291. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagby GC, Lipton JM, Sloand EM, Schiffer CA. Marrow failure. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2004:318–336. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moldovan GL, D’Andrea AD. How the Fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:223–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(10):735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrg2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaz F, Hanenberg H, Schuster B, Barker K, Wiek C, Erven V, Neveling K, Endt D, Kesterton I, Autore F, Fraternali F, Freund M, Hartmann L, Grimwade D, Roberts RG, Schaal H, Mohammed S, Rahman N, Schindler D, Mathew CG. Mutation of the RAD51C gene in a Fanconi anemia-like disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):406–409. doi: 10.1038/ng.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoepker C, Hain K, Schuster B, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Rooimans MA, Steltenpool J, Oostra AB, Eirich K, Korthof ET, Nieuwint AW, Jaspers NG, Bettecken T, Joenje H, Schindler D, Rouse J, de Winter JP. SLX4, a coordinator of structure-specific endonucleases, is mutated in a new Fanconi anemia subtype. Nat Genet. 2011;43(2):138–141. doi: 10.1038/ng.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dallapiccola B, Porfirio B, Mokini V, Alimena G, Isacchi G, Gandini E. Effect of oxidants and antioxidants on chromosomal breakage in Fanconi’s anemia lymphocytes. Hum Genet. 1985;69(1):62–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00295530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joenje H, Eriksson AW, Frants RR, Arwert F, Houwen B. Erythrocyte superoxide dismutase deficiency in Fanconi’s anemia. Nature. 1978;290(8057):142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindler D, Hoehn H. Fanconi anemia mutation causes cellular susceptibility to ambient oxygen. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43(4):429–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrovic S, Leskovac A, Kotur-Stevuljevic J, Joksic I, Guc-Scekic M, Vujic D, Joksic G. Gender-related differences in the oxidant state of cells in Fanconi anemia heterozygotes. Biol Chem. 2011;392(7):625–632. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auerbach AD. A test for Fanconi’s anemia. Blood. 1988;72(1):366–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auerbach AD. Diagnosis of Fanconi anemia by diepoxybutane analysis. In: Dracopoli NC, editor. Short Protocols in Human Genetics: a Compendium of Methods From Current Protocols in Human Genetics. Hoboken: J Wiley; 2004. pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasaki MS, Tonomura A. A high susceptibility of Fanconi’s anemia to chromosome breakage by DNA cross linking agents. Cancer Res. 1973;33(8):1829–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wegner R-D, Stumm M. Diagnosis of chromosomal instability syndromes. In: Wegner R-D, editor. Diagnostic Cytogenetics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1999. pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaffer LG, Tommerup N, editors. An International System for Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN 2009) Basel: S. Karger; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auerbach AD, Rogatko A, Schroeder-Kurth TM International Fanconi Anemia Registry. Relation of clinical symptoms to diepoxybutane sensitivity. Blood. 1989;73(2):391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alter BP. Fanconi’s anemia and malignancies. Am J Hematol. 1996;53(2):99–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199610)53:2<99::AID-AJH7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dokal I, Vulliamy T. Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Haematologica. 2010;95(8):1236–1240. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.025619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmer C, Sanchez S, Ramos S, Molina B, Frias S, Carnavale A. DEB test for Fanconi anemia detection in patients with atypical phenotypes. Am J Med Genet. 2004;124(1):35–39. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu JM, Buchwald M, Walsh CE, Young NS. Fanconi anemia and novel strategies for therapy. Blood. 1994;12(84):3995–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Najean Y, Pecking A, Le Danvic M. Androgen therapy in aplastic anemia in childhood. A prospective study of 352 cases. Scand J Haematol. 1976;22(4):343–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kook H, Cho D, Cho SH, Hong WP, Kim CJ, Park JY, Yoon WS, Ryang DW, Hwang TJ. Fanconi anemia screening by diepoxybutane and mitomycin C tests in Korean children with bone marrow failure syndromes. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13(6):623–628. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1998.13.6.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho SH, Kook H, Kim GM, Yoon WS, Cho TH, Hwang TJ. A clinical study of Fanconi’s anemia. Korean J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;4(1):70–77. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilgin H, Akarsu AN, Bokesoy FI. Cytogenetic and phenotypic findings in Turkish patients with Fanconi anemia. Tr J Med Sci. 1999;29(2):151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soulier J, Leblanc T, Larghero J, Dastot H, Shimamura A, Guardiola P, Esperou H, Ferry C, Jubert C, Feugeas JP, Henri A, Toubert A, Socie G, Baruchel A, Sigaux F, D’Andrea AD, Gluckman E. Detection of somatic mosaicism and classification of Fanconi anemia patients by analysis of the FA/BRCA pathway. Blood. 2005;105(3):1329–1336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwee ML, Poll EH, van de Kamp JJ, de Koning H, Eriksson AW, Joenje H. Unusual response to bifunctional alkylating agents in a case of Fanconi anaemia. Hum Genet. 1983;64(4):384–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00292372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo Ten Foe JR, Kwee ML, Rooimans MA, Oostra AB, Veerman AJ, van Weel M, Pauli RM, Shahidi NT, Dokal I, Roberts I, Altay C, Gluckman E, Gibson RA, Mathew CG, Arwert F, Joenje H. Somatic mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: molecular basis and clinical significance. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5(3):137–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross M, Hanenberg H, Lobitz S, Friedl R, Herterich S, Dietrich R, Gruhn B, Schindler D, Hoehn H. Reverse mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: natural gene therapy via molecular self-correction. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;98(2–3):126–135. doi: 10.1159/000069805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Youssoufian H. Natural gene therapy and the Darwinian legacy. Nat Genet. 1996;13(3):255–256. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castella M, Pujol R, Callén E, Ramírez MJ, Casado JA, Talavera M, Ferro T, Muñoz A, Sevilla J, Madero L, Cela E, Beléndez C, de Heredia CD, Olivé T, de Toledo JS, Badell I, Estella J, Dasí Á, Rodríguez-Villa A, Gómez P, Tapia M, Molinés A, Figuera Á, Bueren JA, Surrallés J. Chromosome fragility in patients with Fanconi anaemia: diagnostic implications and clinical impact. J Med Genet. 2011;48(4):242–250. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.084210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]