Abstract

Assessment has become a major aspect of accreditation processes across all of higher education. As the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) plans a major revision to the standards for doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) education, an in-depth, scholarly review of the approaches and strategies for assessment in the PharmD program accreditation process is warranted. This paper provides 3 goals and 7 recommendations to strengthen assessment in accreditation standards. The goals include: (1) simplified standards with a focus on accountability and improvement, (2) institutionalization of assessment efforts; and (3) innovation in assessment. Evolving and shaping assessment practices is not the sole responsibility of the accreditation standards. Assessment requires commitment and dedication from individual faculty members, colleges and schools, and organizations supporting the college and schools, such as the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Therefore, this paper also challenges the academy and its members to optimize assessment practices.

Keywords: assessment, standards, accreditation

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) plans to revise their standards and guidelines for doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs.1 A stakeholder’s conference was held in October 2012 to gather critical feedback on the state of pharmacy practice and education that could be used to inform the next version of standards for accreditation. Given the complex and ever-changing political environment within higher education, coupled with increasing demands on resources for both accreditors and the institutions they certify, it is important for members of the academy to periodically review standards and processes and to approach revision thoughtfully. This examination should be done with an eye toward the literature and evidence in higher education.2 ACPE’s plan to revise the standards provides an excellent opportunity to revisit the overall approach to assessment standards for PharmD programs. As assessment professionals in colleges and schools of pharmacy, the authors feel the obligation to comment on and share recommendations related to how assessment is addressed and operationalized in the upcoming standards revision. This paper sets forth recommendations intended to help strengthen and streamline assessment in the requirements for accreditation.

In addition, the authors intend for these recommendations to create dialogue and debate in the academy. Evolving and shaping assessment practices is not solely the responsibility of accreditation standards. This process requires commitment and dedication from individual faculty members, colleges and schools, and organizations supporting the college and schools, such as the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP). Therefore, this paper also challenges the academy to optimize assessment practices.

Any discussion of the future of assessment should begin with an understanding of the purpose, supporting structures, and the best practices that have accumulated to date. Assessment strategies and techniques are generally undertaken to gather data to be used to improve or to judge the worth of a performance, program, or entity (ie, accountability). Most often accreditation processes are associated with the accountability agenda for assessment. Indeed, the entire process of preparing a self-study report, being evaluated by a site team, and receiving an accreditation action is by definition a summative assessment of a program and thus can be defined as an accountability exercise. Administrators and educators may resonate more with the formative or improvement aspects of assessment practices, asking “How can we use data driven approaches to improve student learning, or improve the outcomes of programs or courses?” Both improvement and accountability roles for assessment are important and both should be included in the fabric of the standards that are used to determine accreditation of educational programs.

The fundamental role of accreditation in higher education is ensuring quality. In the United States, both the US Department of Education (USDE) and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) play important roles in ensuring the quality and effectiveness of accrediting bodies such as the ACPE. By a process known as recognition, which is similar to the accreditation process, accrediting bodies can be certified by USDE to ensure that they are maintaining the soundness of institutions and programs that receive federal funds. CHEA ensures that accrediting bodies contribute to maintaining and improving academic quality. As such, both CHEA and USDE have their own set of standards and recognition processes, and ACPE is recognized by both. USDE reviews ACPE every 5 years and CHEA reviews them every 10 years. Often these recognition standards translate into requirements seen in the standards for professional programs. For example, USDE requires that accreditors examine an institution’s success with respect to meeting their stated mission.3 This is in turn operationalized into ACPE standard 3 on evaluation of mission and goals for colleges and schools of pharmacy.1

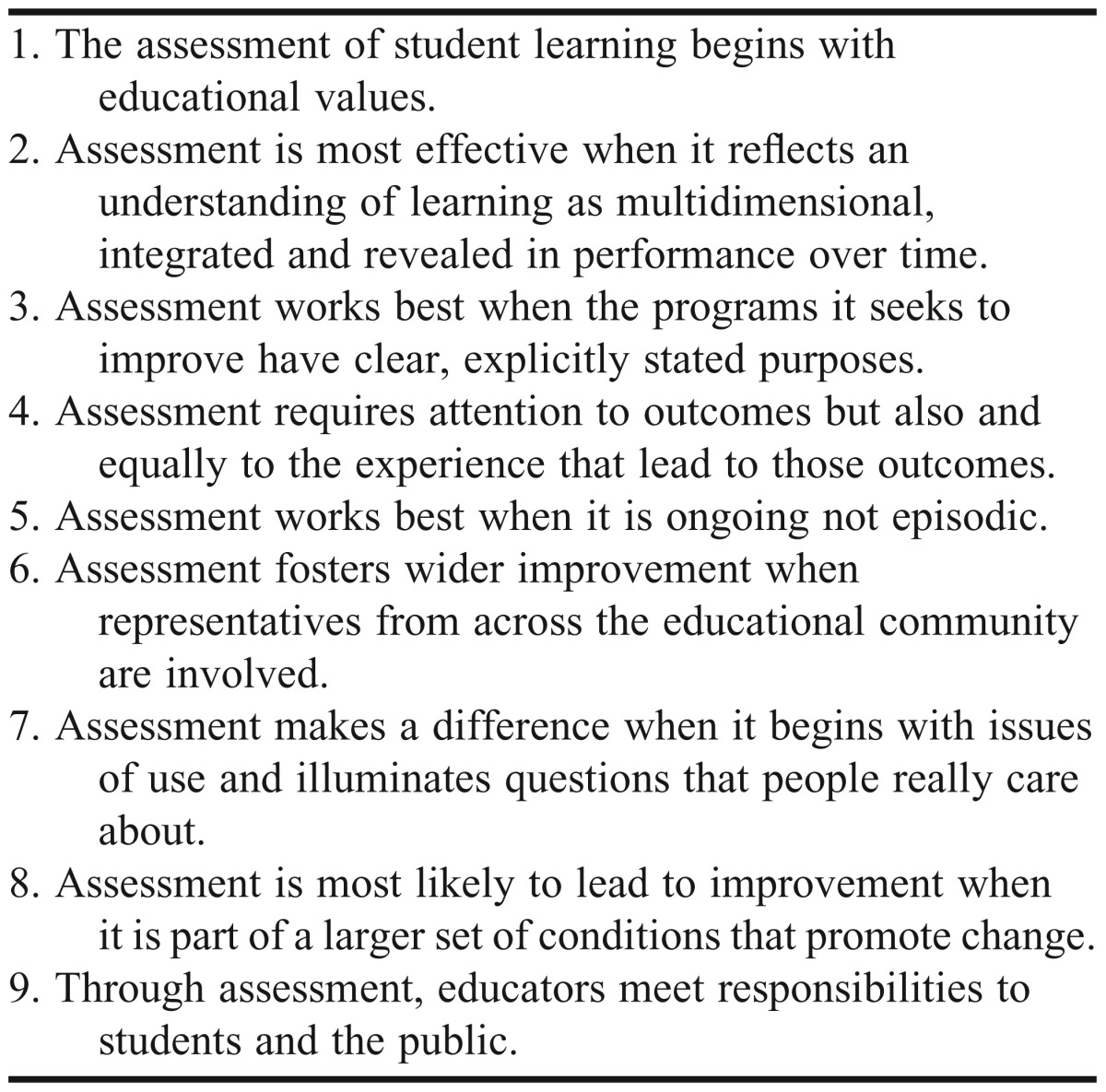

More than 20 years ago the American Association of Higher Education Assessment released “Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning.” 4 This document has been widely used in higher education. The principles were written with the intention of providing guidelines to lead institutions in making a difference by improving student learning through assessment (Table 1).5 Therefore, these principles address the improvement agenda for assessment and provide a grounded framework for the evolution of assessment practices and any recommendations for assessment for the next accreditation standards.

Table 1.

Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning4

This statement specifically addresses 3 goals that the authors recommend for evolving assessment in PharmD programs: (1) simplified standards with a focus on accountability and improvement, (2) institutionalization of assessment efforts, and (3) innovation in assessment.

GOALS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Goal 1: Simplified Standards With a Focus on Accountability and Improvement

The accreditation standards need to be simplified and this goal should be accomplished through a greater focus on assessment plans rather than assessment methods. In the Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree (hereafter referred to as “Standards 2007”), there are 30 standards and 151 guidelines. This is 2 to 3 times the number of accreditation standards for most other health professions colleges and schools.6 Up to 136 documents and/or data reports (required and optional) are requested for a self-study.7 Thirty-eight of these appear in multiple standards. In a profession marked by efficiency, a standards revision should result in reducing redundancy while maintaining high quality.

Guidelines, while originally intended to clarify the standards, have become numerous and wide ranging, with several potential negative effects. In order to meet “should” and “must” guidelines, colleges and schools are developing new programs or policies even though their existing programs or policies may have been sufficient to meet the standard’s intent. For example, standard 15 calls for the assessment and evaluation of student learning and curricular effectiveness. Colleges and schools can assess and evaluate through several methods including, but not limited to, embedded assessments, mile marker examinations, objective structured clinical examinations, national examinations, and/or portfolios. However, guideline 15.1 recommends portfolios and nationally standardized assessments (eg, Pharmacy Curriculum Outcomes Assessment ).1 Mired in a list of “should” statements, colleges and schools run the risk of pursuing the assessments named without fully considering alternative assessment methods or the need and purpose for a given assessment in their particular context. As an alternative to detailed guidelines recommending specific assessment methods, the authors recommend a focus on assessment plans. A strong assessment plan selects and uses methods most appropriate for a given college or school of pharmacy.8

Nationally, accreditation and assessment are shifting from being input-based to outcome-based.8 Standards 2007 includes several strong outcome standards, most notably standard 15 on “Assessment and Evaluation of Student Learning and Curricular Effectiveness.” However, Standards 2007 still contains several input standards. Many of the input standards fall within the standards for faculty and staff (standards 24-26) and the standards for facilities and resources (standards 27-30). Standards and guidelines in these areas focus on counting inputs to a pharmacy education (eg, library volumes, faculty degrees, types of facilities) rather than a college or school’s ability to achieve the outcome of well-educated pharmacists. Inputs proven to correlate with a college or school’s desired outcome should remain in an assessment plan, but do not warrant inclusion in revised ACPE standards.2

Each college and school has unique assets and constraints. In order to ensure student learning while acknowledging these assets and constraints, institution-specific decisions regarding assessment methods are needed. To this end, the authors recommend that the new standards focus on a college or school’s plan for assessment, as well as the evidence of implementation of the plan and the use of results for positive change. Assessment ultimately measures a college’s mission and goals, and therefore no 2 assessment plans are the same.9

Simplifying standards in favor of a focus on assessment plans has several advantages. First, when colleges and schools have a strong voice in what they are assessing and the assessment methods they will use, the information produced is more likely to be used.4 A cycle of assessment forms wherein information is gathered, analyzed, and processed, programs are changed and updated, and information is gathered again.10 A focus on assessment plans fosters both the accountability and improvement goals of assessment and facilitates many of the principles of good practices for assessing student learning (Table 1).

In addition, as faculty members and other stakeholders see the utility of a transparent assessment process organized in a strong assessment plan, a culture of assessment is formed. In turn, a strong assessment plan and culture of assessment create scaffolding for innovation. The assessment plan identifies an area in need of improvement. Within a culture of assessment, faculty and staff members are free to design new ways to solve the identified problem that is a good fit within their existing programs, resources, and goals.

Recommendation 1. Require college- or school-specific plans for student learning outcomes assessment instead of prescribing specific assessment methods. Institutional (or programmatic) assessment focuses on understanding how well the institution is achieving its mission and goals.11 The current standards state expectations for this level of assessment in “Standard 3: Achievement of Mission and Goals.” A college or school’s programmatic assessment often includes indicators of student success, such as job placement and licensure rates, as well as measures of student learning. In other words, student learning outcomes assessment is a subcomponent of program assessment. Similar to program-level assessment, plans for student learning outcomes assessment are vital to success.

The next ACPE standards and guidelines should explicitly require an assessment plan that emphasizes achievement of student learning outcomes and documents curricular effectiveness. Fundamentally, an assessment plan is a written statement of agreement that describes the measures and processes to be used in examining the educational program.12 The plan is developed with significant input from faculty members, professional staff members, students, and administrators. In addition, alumni, employers, and organizational leaders may provide useful input.9 Palomba and Banta advise that “The plan must be seen as a starting point for conducting the assessment program, not the final word.”12

Assessment planning begins with a discussion of assessment’s purposes.9 In addition to improvement and accountability purposes, assessment plans must recognize the needs of relevant external audiences for assessment information, including accrediting bodies. However, the plan should also recognize the college or school’s mission, incorporating assessment of college or school specific foci or strengths (eg, marks of distinction, points of pride).12 A strong assessment plan must have the support of upper administration.8

The goals and objectives for learning are the basis for evaluation. Therefore, defined student learning outcomes are needed.8,9,11,12 An outcomes-based education has been stressed by the academy and the only way to achieve this goal is via well-defined competencies.11 Assessment plans must also include the methods, instruments, and activities that will be used by the institution. These assessments are selected with attention to the relevance and usefulness of the information that would be collected.12 A mixture of direct measures, where students are required to display their knowledge and skills, as well as indirect measures, where students reflect on their learning and abilities, is needed.9 In addition, consideration should be given to the balance of objective tests and performance measures, as well as the balance of quantitative and qualitative methods. Finally, to increase confidence in making changes, multiple measures are recommended.

A timeline for administration of the major components must also be included along with provisions for administering the plan (ie, roles and responsibilities).12 In addition, the plan should also include some examination of anticipated costs, including costs related to faculty development efforts.

Importantly, the framework for using assessment information must be described. This description should outline the anticipated analysis of data, types of reports that will be prepared, and intended audiences, as well as the mechanisms for discussion, review, and decision making based on the assessment data. The results of assessment should be linked to other educational processes such as curriculum review.9,12

Emphasis on assessment plans is consistent with other health professions accreditation agencies. Although not all of the other health professions’ accreditation agencies specifically require assessment plans for student-learning outcomes, 8 require formal ongoing assessment of programmatic effectiveness.13-20 The level of detail required in the self-study varies depending on the accreditation agency. Most of the agencies do not require specific assessment methods.13,14,18-20

To enhance accountability, programs must routinely evaluate their assessment plans. The next version of ACPE standards and guidelines should state an expectation for evaluation of assessment plans. A strong plan will include the specific time and methods to be used for evaluation of the assessment program itself. This evaluation must include whether or not: the assessment process is leading to improvements, appropriate constituencies are represented, problems with the processes have been identified, activities need to be modified, and information is being made available to the appropriate groups.12 In addition, Palomba and Banta suggest 4 criteria to be used in evaluating assessment processes, modified from the Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation. These criteria include utility, feasibility, propriety, and accuracy. Consideration should also be given to continuity of assessment over time, to allow for determination of trends, and at critical junctures, such as pre-post curriculum change. A final consideration is flexibility. Colleges and schools must have the flexibility to experiment and to make changes as the successfulness of the assessment plan is evaluated.9 Colleges and schools are encouraged to consider these criteria in evaluating assessment plans.

Recommendation 2: Require evidence of use of student learning assessment data to influence programmatic change. To enhance improvement in curricula, programs must routinely use data from assessment plans to create change. Evidenced-based processes and practices are becoming increasingly important in an ever-changing world. Patients receive care based on the weight of evidence that given treatments or medications will address their ailments. Similarly, educational changes including curricular reform, should be based on data that support the need for such efforts. While the current standards state that colleges and schools “must use the analysis of outcome measures for continuous improvement of the curriculum and its delivery,” evidence is not required.1 To enhance accountability, the next version of the ACPE standards should explicitly require evidence of programmatic change based on the use of student learning assessment data.

As outlined in the Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning (Principle 8), assessment is most likely to lead to improvement when it is part of a larger set of conditions that promote change.4 Strong assessment requires attention to “closing the loop” and ensuring that data are used to create improvements.21 Baker, in a study of 9 institutions, found that the use of evidence for the purpose of studying processes and practices that improve student learning was central to successfully improving student learning outcomes.22

In addition, many pharmacy programs are engaged in or contemplating major curricular change. Successful curricular change is accompanied by a corresponding organizational change process. Kotter has proposed a model for organization change that can be applied to educational institutions undergoing curricular change.23,24 Farris and colleagues argued that assessment can influence and assist with each stage of the organizational change process.25 For instance, assessment evidence can be used in creating direction and momentum for curricular revisions, recognizing progress in improving student learning, and inspiring additional evolution of curricula. When examining assessment data and planning for improvements, colleges and schools are encouraged to not underestimate the significance of organizational change processes that are associated with a major curricular revision.

Given the importance of assessment in directing and supporting curricular change, the next version of the ACPE standards should increase accountability for data use. Blaich recommends creating discussion among a wide array of stakeholders and using these conversations identify 1 to 2 areas to focus for improvement efforts and resources.26 Colleges and schools should provide evidence of data-driven discussion and prioritization of improvement efforts as part of the accreditation process. In addition, a number of health professions accreditation agencies require a description of curricular revisions based on assessment data.13,15,16,19 Colleges and schools should be required to provide descriptions of curricular revisions based on student learning assessment data.

Recommendation 3: Refine the assessment guidelines by using an assessment appendix to provide alternatives. To further encourage innovation, the next version of the ACPE standards and guidelines should move many of the “should” statements in the current guidelines to a separate appendix. Statements within the guidelines are often interpreted as “must” statements because no alternatives are provided. Use of an Assessment Appendix could encourage alternative approaches to achieve assessment priorities by providing multiple examples of methods to address various types of assessment concerns. The content of this guidance document could be revised and expanded over time as assessment practices evolve as a science. The AACP’s Assessment Special Interest Group should convene a task force to assist with the development of an evidence based guidance document for consideration by ACPE. Unlike the accreditation standards themselves, which rightfully require extensive review and discussion prior to revision, the proposed guidance document might be revised using a less time-consuming, fast-track process.

Goal 2: Institutionalization of Assessment Efforts

Strong programmatic and student learning assessment requires considerable planning and investment. An identified person (or team) leading assessment can provide direction, expertise, and dedicated time. However, as assessment practices expand and become institutionalized, deliberate efforts and strategic decisions must be made in order to sustain and continue to evolve assessment. Several strategies are needed to ensure a meaningful and productive assessment program within a college or school of pharmacy.

Recommendation 4: Integrate assessment with the CQI process. Successful implementation of assessment plans involves active engagement in the assessment cycle. This cycle is based on the elements of continuous quality improvement (CQI), a systematic approach of analysis that uses the principles of scientific inquiry and centers around continual improvement based on data in an effort to meet or exceed customer expectations.27-30 Although it may not be clear to busy faculty members and administrators, assessment and CQI are closely linked. The CQI process is customer focused, driven by a goal, and based on data that suggest a need for improvement.30 Application of CQI principles to higher education has been described in the literature by pharmacy31,32 and other health-related disciplines including nursing,30 physician’s assistant,27 and medical29 training programs.

The concept of assessment being an ongoing rather than episodic process is consistent with the fifth principle of Good Practices.4 Not uncommonly, the Plan-Do-Check-Adjust (PDCA) cycle is used to implement the CQI process. PDCA allows for a continuous cycle for identifying a problem, defining and gathering data needed to assess the problem, taking action to resolve the problem, checking whether the intervention was effective at addressing the problem, and adjusting the plan as needed to allow for further improvement.27

A key element of the CQI process requires that the college or school think strategically and analytically about the data that are needed to address a given curricular problem so that targeted interventions can occur that lead to product improvement.33 In higher education, that product should be the student and the learning that takes place in the student.34 The CQI process allows for colleges and schools to ensure accountability while also remaining sufficiently flexible to allow for continuous improvement in their programs.

The next ACPE standards should increase accountability for integration of assessment data into CQI initiatives within a college or school. Colleges and schools should use the PDCA cycle for assessment and share the data with appropriate support structures in a way that allows for continuous improvement. Assessment data should be considered, when appropriate, in decisions relating to curricular changes, accreditation processes, annual budgeting and other strategic planning initiatives.

Recommendation 5: Promote a culture of assessment. Typically, culture is considered a “shared system of meaning” among individuals that influences their behavior and decisions. Considering this definition, administrators and educators must determine what a culture of assessment is and how it can be established in colleges and schools of pharmacy. In the following guidelines, ACPE implies that a culture of assessment should be established within colleges and schools of pharmacy:

• Guideline 1.6: The college or school’s value should include a stated commitment to a culture that, in general, respects and embraces quality assurance and continuous quality improvement through assessment and evaluation.

• Guideline 15.2: A system of evaluation of curricular effectiveness must be developed that, in general, should…include input from faculty, students, administrators, preceptors, practitioners, state board of pharmacy members, alumni, and others.1

Creating a culture of assessment can be a difficult endeavor as faculty members may have preconceived beliefs concerning assessment.35 Faculty members feel overcommitted and may consider assessment as one more thing they are required to do or as an educational fad. Furthermore, they may view these activities as “unfunded” mandates and see little being done with the data. In contrast, there may be fears on how the assessment data will be used, in particular, whether data will be used against them. They may see themselves as already “doing” assessment through their individual activities and see programmatic assessment as limiting their academic freedom. Identifying and addressing faculty concerns are key components of creating a culture of assessment at any institution.36

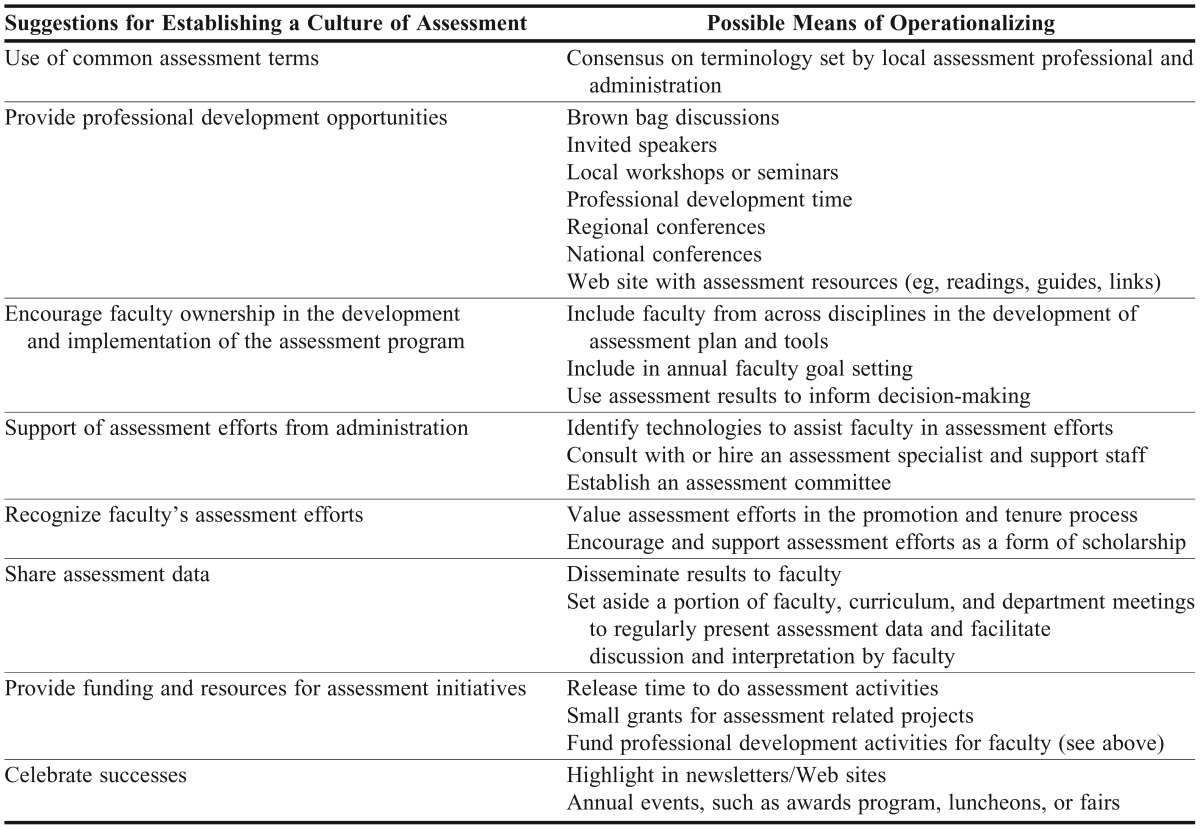

Though there is limited discussion of establishing an assessment culture in the pharmacy literature, recommendations and descriptions of others’ experiences have been published in the higher education literature.10,35,37-39 Among the recommendations, several themes emerge, including the use of common assessment terms, provision of professional development on the assessment of student learning outcomes, faculty ownership of development and implementation of an assessment program, administrative support and understanding of assessment efforts, recognition of assessment efforts in faculty evaluation and departmental reviews, sharing of assessment data, providing funding and resources for assessment initiatives, and celebrating successes. Consistent with the sixth principle of good practices,4 all key stakeholders (faculty and staff members) must be included in the process, in order to have a culture of assessment.

In order to optimize the effectiveness of assessment practices, colleges and schools should work to create a culture of assessment. The next ACPE standards should require that colleges and schools make explicit efforts at establishing a culture of assessment, which would include identifying and addressing faculty concerns. The ACPE standards should not be prescriptive in how colleges and schools encourage a culture of assessment, as each institution is unique. Colleges and schools may want to consider the recommendations for establishing a culture of assessment presented in this paper (Table 2) and identify appropriate actions for their college or school. AACP should serve as a resource to colleges and schools by providing assistance and by developing programming for faculty members and administrators.

Table 2.

Methods in Creating a Culture of Assessment10,35,37-39

Recommendation 6: Foster engagement and collaboration in assessment. Hutchings has argued that “the real promise of assessment depends on significantly growing and deepening faculty involvement.”40 The next ACPE standards should encourage broad, substantive involvement and productive collaboration in assessment-related activities. Colleges and schools should nurture assessment involvement by faculty and staff members. As researchers and scholars, faculty can readily appreciate and value an evidenced-based process of inquiry to inform their teaching and student-learning improvement activities. Faculty members are most likely to embrace teaching and learning assessment if: (1) it helps them do their best work, (2) it improves student outcomes, and (3) it is rewarded activity.34 The potential to involve staff members, such as student affairs professionals, is often overlooked and underused.41

Quality assessment requires involvement of and collaboration between individuals. Collaboration in assessment activities can help share the workload, aid motivation, and produce stronger projects.42 Colleges and schools are urged to consider opportunities for collaboration. Opportunities for collaboration may exist between departments within the school or may be available across local health professions programs. Opportunities may also exist with other pharmacy schools in the geographic area and/or with pharmacy colleges and schools with similar missions and operations. Collaborations are a strategic decision and an investment that can significantly assist the program in meeting its goals by evolving into rich communities of practice.43

Goal 3: Innovation in Assessment

The current ACPE guidelines already call for colleges and schools to foster and assess experimentation and innovation in their plans to address curricular effectiveness (guideline 15.2).1 In order to address reluctance in developing new assessment approaches, the next ACPE standards should outline expectations related to innovation. For instance, innovations must be carefully planned. Innovations should be initiated based on a clear rationale and/or a documented need. Plans for innovations must draw on related literature and existing evidence where available. Consequences for poor student performance based on a new, innovative assessment should be no-stakes or low stakes. Adequate student feedback and remediation should be provided. Innovations should be designed to be feasible given the resources available. Pilot projects in assessment should be encouraged. Pilots may involve a portion of students, a focused scope of knowledge, skills, attitudes or behaviors and/or be limited in some other fashion. Innovations can then be “scaled up” as experience is gained.

Innovations must be closely monitored and evaluated. The goal of innovation is to produce assessment evidence that is ideally direct, relevant, verifiable, representative, cumulative and, importantly, actionable.44 Criteria for success should be outlined prior to launching the innovation, as well as the individuals or group responsible for the evaluation and the timeline for evaluation. Communication with faculty members, staff members, and students regarding the innovation project should be encouraged. Colleges and schools should promote assessment-related innovations by providing faculty members time to pursue innovative projects, arranging for staff and/or consulting support, encouraging documentation of innovations in annual reporting, recognizing work related to innovations in annual reviews, and discussing innovations in college and school communications.

Recommendation 7: Promote and nurture scholarship in assessment. Standards 2007 requires (standard 25) faculty members to be “committed to the advancement of the profession and the pursuit of research and other scholarly activities.”1 To support improvement in pharmacy education, the academy, with support from AACP, must recognize and continue to encourage the importance of the scholarship of assessment. Just as colleges and schools expect students to embrace innovation, internalize scientific methodology, develop evidence-based practices, and exhibit leadership, so should institutions and accreditation bodies expect faculty assessment practitioners to do likewise. “If the academy wants to model innovation and leadership to its students, an active program of research is essential.” 6

Assessment is scientific inquiry similar to faculty scholarship in other facets of academic work. Framing the discussion of assessment as a scholarly activity occurring in the classroom (or college) can assist in gaining faculty buy-in to assessment efforts. As Abate, Stamatakis, and Haggett recommended in 2003, colleges and schools should “add well-designed, documented, and evaluable assessment-related practices to the definition of the scholarship of teaching and learning.”8 Colleges and schools should provide time for assessment-related scholarship, as well as recognizing the scholarship of assessment as part of promotion and tenure decisions.

To benefit other institutions, colleges and schools should encourage faculty and assessment professionals to disseminate advancements and innovations at AACP meetings and in the Journal. As an organization, AACP should continue to support the development of mechanisms that can be used at national, regional, and local levels to recognize and encourage the scholarship of teaching, learning, and assessment. In particular, AACP should advocate that the scholarship of assessment be rewarded at the college or school level in the same ways as other scholarship.

Recommendation 8: Encourage advancements in the assessment of the affective domain. One of the challenges that assessment professionals are struggling with is assessing outcomes that fall within the affective domain. The proposed Assessment Appendix (see Recommendation 3) would facilitate the efforts of institutions to build college- or school-specific assessment plans that incorporate the affective domain.

The affective domain includes a number of highly relevant topics requiring attention. For instance, current ACPE standards and guidelines call for the assessment of professionalism in our students,1 but the instruments and processes to be used for this assessment require further investigation. The development of other affective traits such as leadership and advocacy, self-assessment, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurship are believed to be important for the preparation of pharmacists who can be effective and thrive in practice models designed to maximize their contributions to society.45 In addition, the anticipated inclusion of some of these harder-to-measure affective outcomes in the forthcoming revision of the AACP CAPE standards suggests the need for colleges and schools to develop innovative approaches to their measurement.

Additionally, ACPE standards and guidelines, version 2.0, contains multiple mentions of interprofessional team goals and activities. Assessing teamwork is particularly in need of flexibility to allow creation of validated measurement approaches. In 2009, the national education associations of 6 health professions formed a collaborative called The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC, https://ipecollaborative.org/). Through its reports (https://ipecollaborative.org/Resources.html), the IPEC Collaborative has developed core competencies and strategies to implement these core competencies. However, assessment of these interprofessional competencies is in its infancy.

On a broader plane, the successful combination of data from multiple existing assessments could offer efficiencies of effort and cost. ACPE requires several standardized assessments, such as the curriculum quality surveys; however, the most useful and informative balance between local assessment and the standardized assessments has yet to be found. At the highest level of assessment, there is yet no assessment to predict how well pharmacy graduates will perform when they are several years into their careers. In addition, innovation, scholarship, and collaboration in the affective domain are needed, in order to advance the academy’s ability to foster student learning. Colleges and schools are urged to focus efforts in this area.

SUMMARY

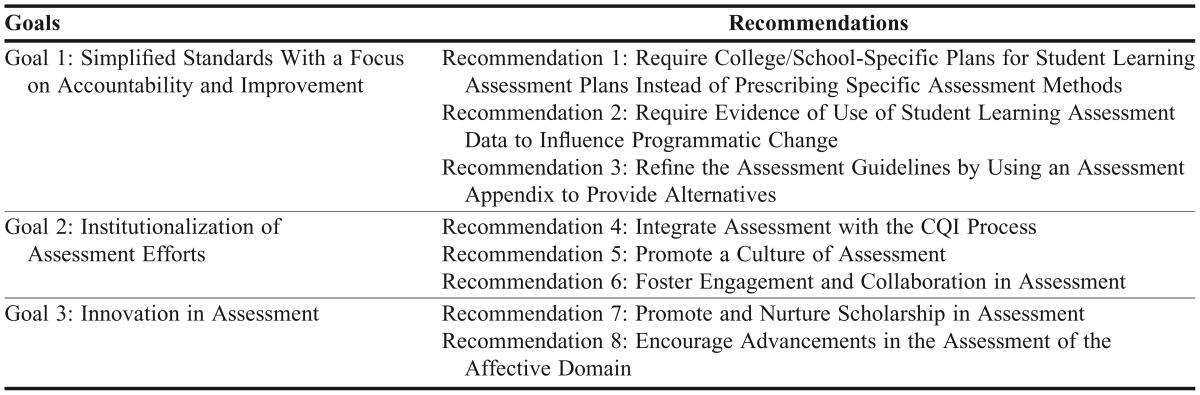

The upcoming revision of the accreditation standards for PharmD programs provides an outstanding opportunity to help shape the way colleges and schools of pharmacy approach the assessment of their mission and demonstrate the educational outcomes of their training programs. The academy has the opportunity to showcase its efforts and strengthen approaches to display innovation and scholarship in the area of educational assessment of its graduates. The authors anticipate that the goals and recommendations offered herein, which are summarized in Table 3, serve as a basis for dialogue and debate within ACPE and the academy in seeking to improve the practice of pharmacy by strengthening the educational programs of colleges and schools.

Table 3.

Summary of Goals for New Assessment-Related Standards/Guidelines and Associated Recommendations

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Inc. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/standards.asp. Accessed February 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray FB. Six misconceptions about accreditation in higher education. Change. 2012;44(4):52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eaton JS. An overview of US accreditation. Council for Higher Education Accreditation. August 2012. http://www.chea.org/Research/index.asp#overview. Accessed January 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astin AW, Banta TW, Cross P, et al. Principles of good practice for assessing student learning. December 1992. American Association for Higher Education. http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/PrinciplesofAssessment.html. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchings P, Ewell P, Banta T. AAHE principles of good practice: aging nicely. 2012. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/PrinciplesofAssessment.html. Accessed February 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svensson CK, Ascione FJ, Bauman JL, et al. Are we producing innovators and leaders or change resisters and followers? Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(7):Article 124. doi: 10.5688/ajpe767124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Documentation and data required for self-study report (rubric v4.0, April 2011) https://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/resources.asp. Accessed January 22, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abate MA, Stamatakis MK, Haggett RR. Excellence in curriculum development and assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 89. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palomba CA, Banta TW. Assessment Essentials: Planning, Implementing and Improving Assessment in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990. The essentials of successful assessment; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suskie LA. Assessing Student Learning: A Common Sense Guide, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson HM, Moore DL, Anaya G, Bird E. Student learning outcomes assessment: a component of program assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2):Article 39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palomba CA, Banta TW. Assessment Essentials: Planning, Implementing and Improving Assessment in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1999. Developing definitions, goals and plans; pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education. CAPTE accreditation handbook. http://www.capteonline.org/AccreditationHandbook/. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education. ACOTE accreditation. http://www.aota.org/en/Education-Careers/Accreditation.aspx. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Optometric Association. Optometric degree programs resources. Accreditation Council on Optometric Education. http://www.aoa.org/x12707.xml. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. Inc. Standards of accreditation. http://www.arc-pa.org/acc_standards/. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education. Baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/ccne-accreditation/standards-procedures-resources/baccalaureate-graduate. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Dental Association. Accreditation. http://www.ada.org/100.aspx. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Council on Podiatric Medical Education. Accreditation information for colleges. http://www.cpme.org/colleges/content.cfm?ItemNumber=2445&navItemNumber=2241. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school: LCME accreditation standards. http://www.lcme.org/standard.htm. Accessed March 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maki PA. Assessing for Learning: Building a Sustainable Commitment Across the Institution. Sterling, VA: Stylus; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker GR, Jankowski N, Provezis S, Kinzie J. Using assessment results: promising practices of institutions that do it well. July 2012. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/NILOAReports.htm. Accessed February 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Bus Rev. 2007;1:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farris KB, Demb A, Janke KK, Kelley K, Scott S. Assessment to transform competency-based curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 158. doi: 10.5688/aj7308158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blaich C, Wise K. From gathering to using assessment results: lessons from the Wabash National Study. 2011. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/occasionalpapers.htm. Accessed February 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radawski D. Continuous quality improvement: origins, concepts, problems, and applications. Perspect Physician Assist Educ. 1999;10(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what will it take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593–624. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman MT, Headrick LA, Langley AE, Thomas JX. Teaching medical faculty how to apply continuous quality improvement to medical education. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24(11):640–652. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30412-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yearwood E, Singleton J, Feldman HR, Colombraro G. A case study in implementing CQI in a nursing education program. J Prof Nurs. 2001;17(6):297–304. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2001.28187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ried LD. A model for curricular quality assessment and improvement. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):Article 196. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7510196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Timpe EM, Gupchup GV, Scott VG. Incorporating a continuous quality improvement process into pharmacy accreditation for well-established programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(3):Article 38. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Achieving the Dream. Public Agenda. Cutting Edge Series No. 3: Building institutional capacity for data-informed decision making. 2012 http://www.publicagenda.org/files/ATD_CuttingEdge_No3_FINAL.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hersh RH, Keeling RP. Changing institutional culture to promote assessment of higher learning. Occasional Paper #17. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/occasionalpapers.htm. Accessed February 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown K. Community college strategies: why aren’t faculty jumping on the assessment bandwagon—and what can be done to encourage their involvement. Assess Update. 2001;13(2):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angelo TA. Doing assessment as if learning matters most. AAHE Bulletin. 1999;51(9):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brill RT. A decade of progress: learned principles. Assess Update. 2008;20(6):12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiner WF. Establishing a culture of assessment: fifteen elements of success – how many does your campus have? July/August 2009. http://www.aaup.org/article/establishing-culture-assessment. Accessed February 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennion DH, Harris M. Creating an assessment culture at Eastern Michigan University: a decade of progress. Assess Update. 2005;17(2):7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchings P. Opening doors to faculty involvement in assessment. Occasional Paper #4. April 2010. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/documents/PatHutchings_000.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuh JH. Gansemer-Topf. The role of student affairs in student learning assessment. Occasional Paper #7. February 2013. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/occasionalpapers.htm. Accessed February 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janke KK, Kelley KA, Soliman SR. The power of many: building capacity for assessment through cross institutional collaboration. Assess Update. 2013;25(1)(1):15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janke KK, Seaba HH, Welage LS, et al. Building a multi-institutional community practice to foster assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(4):Article 58. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ewell P. CHEA workshop on accreditation and student learning outcomes. http://www.chea.org/pdf/workshop_outcomes_ewell_02.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mason HL, Assemi M, Brown B, et al. Report of the 2010-2011 Academic Affairs Standing Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):Article S12. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7510S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]