Abstract

Objectives. To identify and characterize postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) pharmacy residency programs with a secondary emphasis on academia.

Methods. Residency programs were identified using the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) online directory of residencies, fellowships, and graduate programs and cross-referenced with the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) residency directory. An electronic questionnaire was developed and sent to residency program directors to collect attributes of each program. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results. Most programs were initiated during the past decade. More than two-thirds were ASHP-accredited and half had a primary specialty in ambulatory care. The average program structure consisted of clinical practice service (50.4%), experiential teaching (18.5%), classroom-based teaching (16.4%), research (10.7%), and service (3.7%). Most residents (90.0%) accepted an academic appointment upon completion of these programs.

Conclusions. Postgraduate year 2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia provide experiences in clinical practice, experiential and classroom teaching, research, and service. These residency programs result in participants obtaining academic positions after graduation.

Keywords: residency, academia, education, teaching

INTRODUCTION

Colleges and schools of pharmacy continue to face faculty shortages. This phenomenon was detailed by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), which documented 378 vacant and lost positions in 2010-2011.1 Of the vacant and lost positions, most (48.1%) were in clinical science and pharmacy practice. Approximately 28% of the vacant positions remained vacant for more than 1 year. Nearly 27% of the positions remained vacant because there were not enough qualified applicants in the pool (ie, candidates being judged unable to meet the expectations or requirements of the academic institution, an inadequate number of qualified candidates in the discipline, and a lack of response to the position announcement). This AACP survey also revealed difficulties with retention as approximately 14% of individuals moved to a practice position in the healthcare private sector. In addition, the number of accredited (full or candidate status) pharmacy degree programs in the United States has increased from 83 to 124 during the past decade, further increasing faculty vacancies.2 Therefore, there is a growing need to recruit qualified faculty members.

The 2002 AACP Task Force on the Role of Colleges and Schools in Residency Training stated that individuals with residency training could assist colleges and schools of pharmacy in many ways: as full-time faculty members, as preceptors to student pharmacists, as administrators at hospitals and clinics who could partner with colleges and schools of pharmacy on a common educational mission, as leaders who could support pharmacy education, and as pharmacist role models for patient care practice.3 In their 2004 Final Report, the AACP Council of Deans-Council of Faculties Faculty Recruitment and Retention Committee also recognized pharmacy residents as prime candidates to prepare for and fill faculty positions. Two recommendations made by the committee were to develop an educational component that would allow residents an opportunity to create and deliver educational programming to student pharmacists and to add teaching as a component to the residency program.4

Efforts to incorporate teaching experiences as part of postgraduate year 1 (PGY1) residency training have been described in the literature. Romanelli and colleagues reported the first teaching certificate training program for pharmacy residents in 2001. Three main requirements of the certificate program were attending formal seminars, completing small group and classroom-evaluated teaching, and submitting a teaching portfolio.5 Graduates also have used the tools gained during a teaching certificate program to help obtain their first faculty position.6,7 A PGY1 residency with an emphasis on academia has also been described. Academic requirements of the residency included providing classroom-based lectures and experiential teaching, assisting with case-based or problem-based group conference seminars, participating in clinical research, and serving as a primary preceptor.8

Postgraduate year 2 pharmacy residency programs are designed to increase the resident’s depth of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and abilities to raise the resident’s level of expertise in the area of focus.9 Although these programs prepare the resident to excel in a specialized area compared to PGY1 programs, they do not always prepare them for a full-time faculty position which consists of extensive activities pertaining to classroom-based and experiential teaching, research, and service. Postgraduate year 2 pharmacy residents generally have limited options to continue refining their teaching skills after completion of PGY1 residency training.10 Medina and colleagues described a teaching certificate program specifically designed for PGY2 residents that could expand these options.11 The residents were prepared for faculty and preceptor positions through advanced topic discussions which included course coordination, grading, active learning, and teaching with technology. A practice-based learning experience designed to provide both PGY1 and PGY2 residents an opportunity to serve as a primary preceptor while being guided and evaluated by a faculty member has also been described in the literature.12 The practice experience exposed the residents to teaching not solely focused on classroom-based teaching and the residents found it to be a valuable experience for a possible career in academia.

Postgraduate year 2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia have also emerged in an effort to better prepare residents for a position at a college or school of pharmacy. For example, one PGY2 community pharmacy residency established in 2009 developed a program to prepare future faculty members by providing advanced training in clinical community practice settings and college and school of pharmacy environments.13 However, little is known about existing PGY2 residency programs that have an emphasis on academia. To the authors’ knowledge, the advanced academic experiences gained during these residency programs have yet to be described in the literature. This study was conducted to identify and characterize PGY2 pharmacy residency programs with a secondary emphasis on academia to gain a better understanding of the training programs in preparing residents for future academic positions and potentially provide information for programs to initiate residencies aimed at academics.

METHODS

Postgraduate year 2 pharmacy residency programs with a secondary emphasis on academia were first identified using the ACCP Online Directory of Residencies, Fellowships, and Graduate Programs. This directory provides information about all residency programs, regardless of whether they are accredited or have submitted accreditation applications. The directory also enables programs to include both a primary and secondary specialty. A search was conducted of all US residency programs based on primary specialty. From the list of programs generated, only PGY2 residency programs that also listed a secondary specialty in academia, education, or teaching were included in the study sample.

The programs identified were then cross-referenced with the ASHP Online Residency Directory. This directory only provided information about residency programs that were accredited or had submitted accreditation applications that were pending. Postgraduate year 2 programs could be selected using the ASHP directory, but the directory did not include a secondary specialty category. The list of PGY2 programs found from the ACCP directory was located in the ASHP directory and the residency special features were reviewed. This cross-referencing with the ASHP directory was performed to validate the ACCP description. Finally, the residency program Web site was reviewed to gather further background information and ensure consistency of the information found from the online directories. Fourteen PGY2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia were found using this search method.

A 22-item questionnaire was created using Qualtrics online survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The UNC Odum Institute, an institute for research and social sciences, was consulted to assist in the design. The first 6 questions of the questionnaire were designed to confirm that the institution did have a PGY2 program with a secondary specialty in academia, education, or teaching, and to gather background information on the program (ie, the primary specialty area, the year the program began, accreditation status). Questions 7 through 11 were intended to determine the output from the residencies; that is, the number of residents completing the programs and whether they were offered and/or accepted an academic position upon completion of the program. Question 12 was designed to determine the percentage of time the resident was expected to devote to academic experiences in clinical practice, classroom-based and experiential teaching, research, and service. Questions 13 through 22 were intended to identify whether and how often the resident was expected to complete specific activities related to classroom-based and experiential teaching, clinical practice, research, and service. Skip logic patterns were built into the online questionnaire so that respondents would only answer questions relevant to their program. The electronic questionnaire underwent face-validation by 3 faculty members, 2 of whom were residency program directors, for appropriateness and functionality. The background, methods, and questionnaire were submitted to the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (IRB) and determined to be exempt from review.

The online questionnaire was then sent to residency directors of the 14 PGY2 programs via electronic mail (e-mail) and remained opened from June 4, 2012, to August 17, 2012. The questionnaire was designed to take approximately 20 minutes to complete and the residency program directors were offered the chance to win a $50 Visa gift card for completing the questionnaire. The e-mail explained the purpose of the questionnaire, stated that participation was voluntary, and included a link to the online questionnaire. Consent was provided by completion of the questionnaire. The introduction to the questionnaire explained that participation was voluntary and that the information provided would be kept confidential. A reminder e-mail was sent 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after launching the electronic questionnaire to residency directors who had yet to respond. One program director who did not respond to the reminder e-mails was called to determine if the survey instrument had been received and subsequently completed the survey instrument. Data were described and presented using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

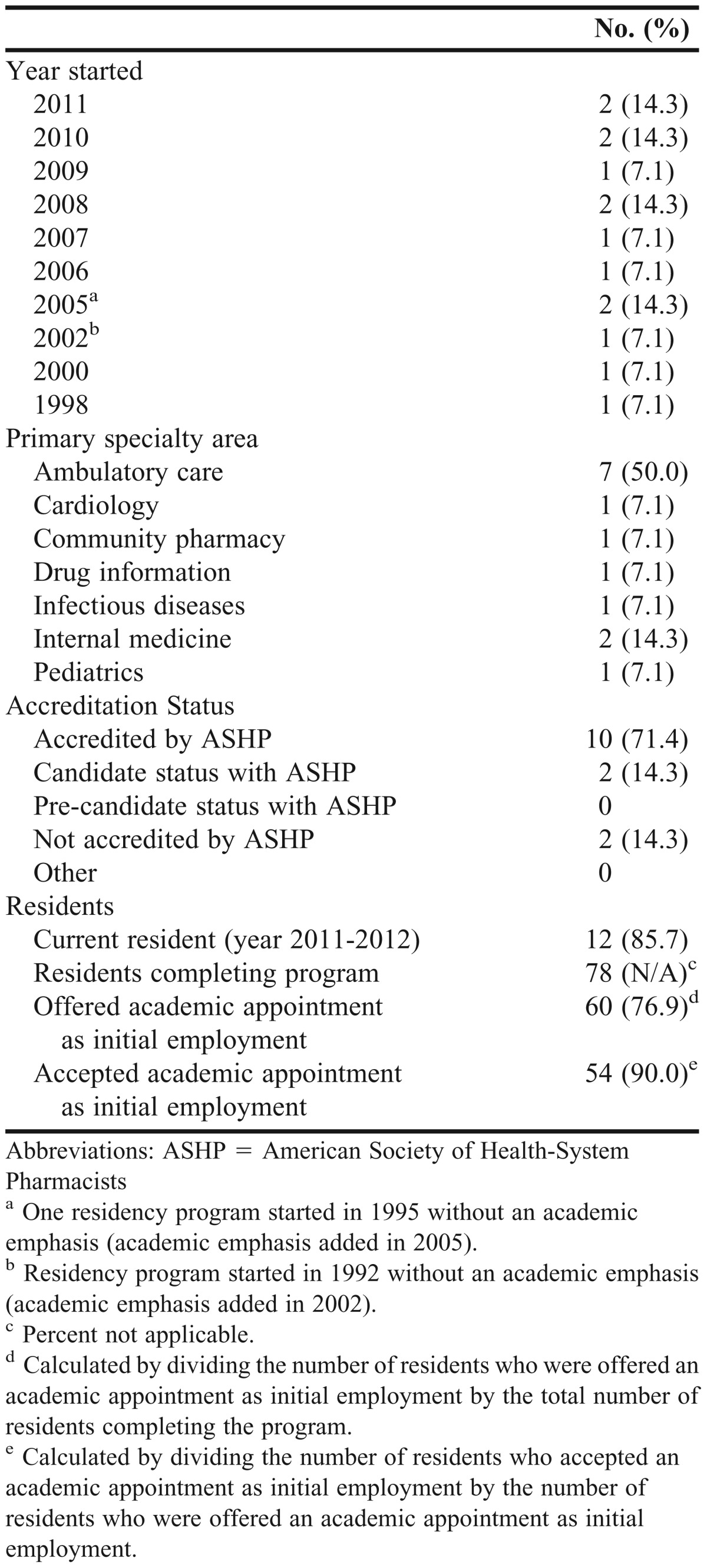

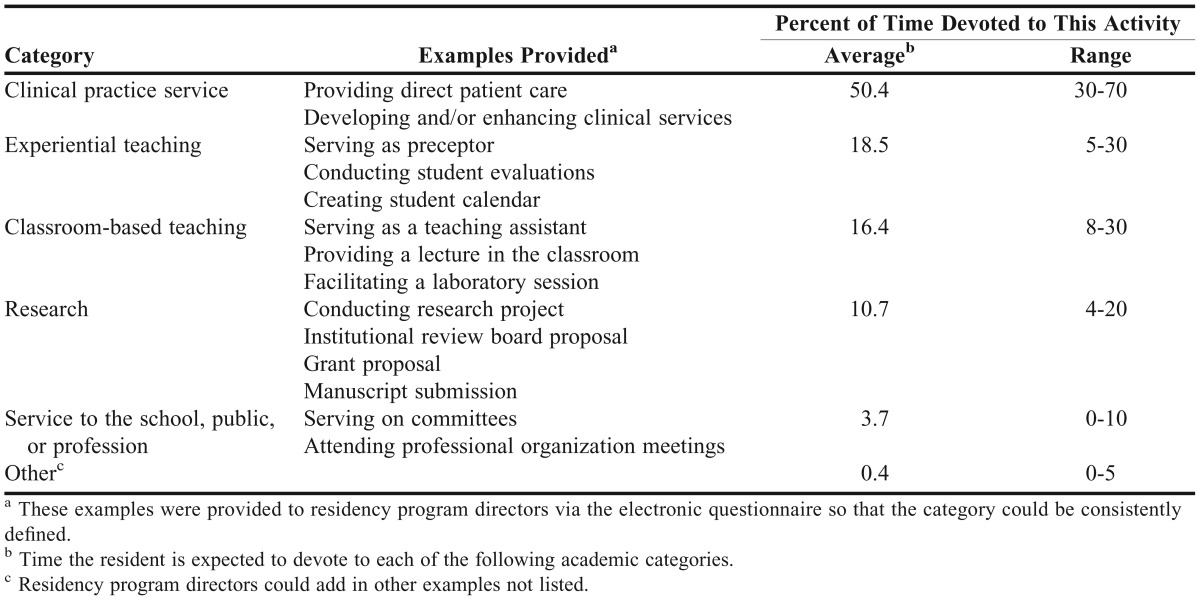

The electronic questionnaire was completed by all 14 residency program directors. The majority of programs (85.7%) were initiated or had an academic component added within the past decade and 2 programs were initiated prior to 2002. Seven programs (50.0%) were initiated within 5 years of this study (Table 1). Half of the programs were in the ambulatory care setting with the remaining half of the programs comprised of 6 other primary specialty areas. Almost three-fourths (71.4%) of programs were accredited by ASHP and 12 programs (85.7%) had at least 1 resident during the 2011-2012 residency year. Of the 78 total residents completing the programs, 60 residents (76.9%) were offered an academic appointment as initial employment. Fifty-four of the 60 residents (90.0%) accepted the position (Table 1). The structure of the residency programs consisted of clinical practice service (50.4%), experiential teaching (18.5%), classroom-based teaching (16.4%), research (10.7%), and service to the school, public, or profession (3.7%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of US Second-Year Pharmacy Residency Programs (N = 14)

Table 2.

Pharmacy Residency Program Structure (n = 14)

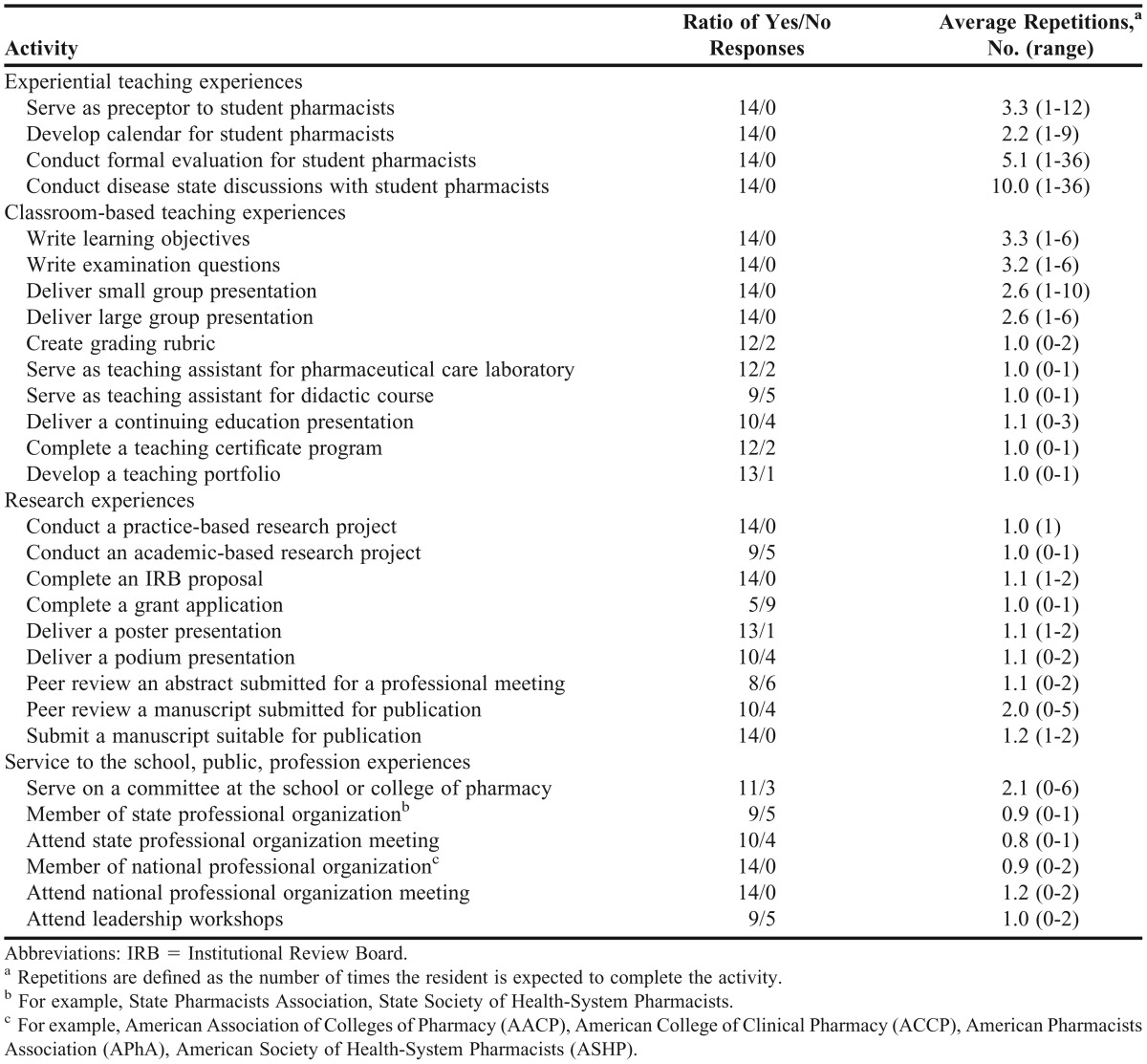

All residency program directors reported enhancing a clinical service as part of residents’ clinical practice responsibilities and more than half (57.1%) of programs provided residents with an opportunity to develop a clinical service. All programs prepared participants to pursue becoming a Board Certified Pharmacotherapy Specialist (BCPS) or Board Certified Ambulatory Care Pharmacist (BCACP) after completion of residency training. Experiential teaching responsibilities provided by all programs included having residents serve as preceptors to student pharmacists, develop a calendar for student pharmacists, conduct formal evaluations, and lead disease state discussions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Academic Experiences Offered by Pharmacy Residency Programs in the United States (n = 14)

Classroom-based teaching experiences common among all programs included writing learning objectives and examination questions, and delivering small and large group presentations. Most programs required residents to develop a teaching portfolio (92.9%), complete a teaching certificate, create a grading rubric, and serve as a teaching assistant for a pharmaceutical care laboratory (85.7%). In addition, approximately two-thirds of programs required residents to serve as a teaching assistant for a classroom-based course and almost three-fourths had residents deliver a continuing education program (Table 3).

Research experiences reported by all residency program directors included conducting a practice-based research project, completing an IRB proposal, and submitting a manuscript suitable for publication. Approximately two-thirds of programs also required residents to complete an academic-based research project and more than two-thirds had the residents peer-review a manuscript submitted for publication. Most programs (92.9%) had the residents deliver a poster presentation and more than two-thirds (71.4%) had the residents deliver a podium presentation. More than half of the program directors reported having the residents peer-review an abstract submitted for a professional meeting and less than half (35.7%) reported having the residents complete a grant application (Table 3).

All program directors reported having the residents become a member of a national professional pharmacy organization and attend a national meeting. Approximately two-thirds of program directors reported having the residents become a member of a state professional pharmacy organization and attend a state meeting. Approximately three-fourths of program directors required that the residents serve on a committee at the college or school of pharmacy and approximately two-thirds required the residents to attend a leadership workshop (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The majority of PGY2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia were started during this past decade with an effort to prepare future faculty members. These programs are graduating residents who are being offered and accepting academic appointments as their initial employment. Within the framework of PGY2 residency training, these programs are able to provide residents with numerous teaching, research, and service opportunities. According to the ASHP Accreditation Standard for PGY2 pharmacy residency programs, the purpose of the second-year residency is to increase the resident’s depth of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and abilities to raise the resident’s level of expertise in the specific area of practice.9 This study revealed that approximately 50% of the residents’ time was devoted to clinical practice service, either developing a new service or enhancing an existing service. The ASHP PGY2 Pharmacy Residency Accreditation Standard also states that in those practice areas where board certification exists, graduates are prepared to pursue such certification. According to the respondents to this survey, all residents were prepared to sit for either the BCPS or BCACP examination, depending on their primary specialty area of practice.

Clinical faculty members are expected to have substantial clinical experience before entering academia but, surprisingly, many have limited experience with classroom-based teaching responsibilities.14 Faculty members often learn a basic teaching skillset on the job, which includes writing learning objectives and multiple-choice questions for class and examinations, and developing continuing education programs. As many schools or colleges of pharmacy do not mandate teacher training for new faculty members, the burden is often placed on the junior faculty member to seek out this training. This survey revealed that residents graduating from a PGY2 residency program with an emphasis on academia were indeed receiving a significant amount of training with regard to teaching. On average, approximately 35% of the residents’ time was devoted to experiential and classroom-based teaching experiences. Residents were independently serving as a primary preceptor to student pharmacists, creating the student calendar, and conducting formal evaluations at their practice sites. They were also serving as teaching assistants, writing examination questions, creating grading rubrics, and delivering presentations and continuing education seminars. In addition, the majority of programs required the residents to complete a formal teaching certificate program and prepare a teaching portfolio.

Junior faculty members are often faced with the challenge of learning and enhancing their skills pertaining to research development during the first few years in their new position. This includes becoming skilled with IRB submission, obtaining grants, and publishing their work.14 Few residency projects actually result in journal publication. When surveyed, faculty members often responded that they had insufficient skill, time, and training when it came to conducting research.15,16 This survey revealed that approximately 10% of the residents’ time was being devoted to research endeavors. Some programs also required the residents to complete a second research project that had an academic focus. To further prepare residents for research responsibilities, some program directors had them complete a grant application, review abstracts and manuscripts submitted for a professional meeting or publication, and present the results of their findings at a professional meeting.

Service responsibilities also remain an important component to the academic institution. Pharmacy faculty members have an obligation to make contributions and improvements to the school, public, and profession. They serve on committees to shape operational and administrative functions, and play an integral role in advancing the goals of the profession through membership and service to professional organizations and societies.17 The respondents in this survey indicated that residents spent approximately 4% of their time providing service to the school, public, and profession. Despite this low percentage of time, residents became members of national professional pharmacy organizations and were encouraged to attend national meetings. In addition, residents became involved with a professional organization at the state level. Many residents also contributed to service activities at the college or school of pharmacy by serving on committees.

While this study has identified and characterized several PGY2 residencies with an emphasis on academia, a few limitations should be noted. Because of the timing of when the electronic questionnaire was launched (approximately 3 weeks prior to completion of the 2011-2012 residency year), residents in these programs with an emphasis on academia may have been waiting on employment offers. This may have affected the percentage of residents offered an academic appointment as initial employment. The search method used cannot guarantee that all PGY2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia were identified. The ACCP and ASHP online residency directories do not primarily categorize PGY2 residency programs using the terms academia, education, or teaching. Also, including a secondary specialty such as academia, education, or teaching using the ACCP online directory is optional and the ASHP online directory does not include a secondary specialty. Of the approximate 350 PGY2 residency programs found using the online directories, only 14 were identified as specifically listing a secondary specialty in academia, education, or teaching. A full, detailed review of all available PGY2 residency programs was not conducted to investigate any emphasis on academia that was not documented in the online directories. This would have required manual review of residency descriptions and potential verification through e-mail or phone contact.

CONCLUSION

Several PGY2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia were initiated during the past decade. The experiences and repetitions gained in clinical practice, classroom-based and experiential teaching, research, and service have allowed many residents in this sample of PGY2 programs to obtain an academic appointment with a college or school of pharmacy as initial employment upon completion of the program. Creating more PGY2 residency programs with an emphasis on academia may serve to better prepare residents for a faculty position and ultimately reduce the shortage of qualified candidates. Future research should follow the growth of this type of residency but also attempt to capture residents’ perspectives both during residency and early in their faculty career.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Joel Farley, PhD, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, and Teresa Edwards, MA, UNC Odum Institute, for their assistance in developing and reviewing the electronic questionnaire. We also acknowledge Sally Morris, UNC Odum Institute, for assisting us with using the Qualtrics online survey software.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vacant budgeted and lost faculty positions-academic year 2010-11, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Institutional Research Brief Number 12. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Documents/IRB%20No%2012%20-%20Faculty%20vacancies.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Academic pharmacy’s vital statistics. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. http://www.aacp.org/about/Pages/Vitalstats.aspx. Accessed March 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee M, Bennett M, Chase P, et al. Final report and recommendations of the 2002 AACP task force on the role of colleges and schools in residency training. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article S2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.AACP. COD-COF faculty recruitment and retention committee final report - June 2004, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. http://www.aacp.org/governance/councildeans/Documents/AACPCommitteeonRetentionFinalReport.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Brandt BF. Certificate program in teaching for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2001;58(10):896–8. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.10.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Getting JP, Sheehan AH. Perceived value of a pharmacy resident teaching certificate program. Am J Pharm Edu. 2008;72(5):Article 104. doi: 10.5688/aj7205104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falter RA, Arrendale JR. Benefits of a teaching certificate program for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(21):1905–1906. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillema S, Ly A. A pharmacy practice residency (PGY1) with an emphasis on academia. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(1):Article 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP accreditation standard for postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) pharmacy residency programs. http://www.ashp.org/s_ashp/docs/files/RTP_PGY2AccredStandard.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrs JC, Fujisaki BS, Marcus KB, et al. Portland pharmacy practice resident teaching certificate (PPRTC) program. Poster presented at Annual Meeting of American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Chicago, IL;2008 July 19-23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina MS, Herring HR. An advanced teaching certificate program for postgraduate year 2 residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2284–2286. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slazak EM, Zurick GM. Practice-based learning experience to develop residents as clinical faculty members. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(13):1224–1227. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. PGY2 community pharmacy residency program. http://pharmacy.unc.edu/programs/residencies/community-pharmacy-residency-program/pgy2. Accessed March 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erstad BL. Surviving and thriving in the academic setting. American College of Clinical Pharmacy Clinical Faculty Survival Guide. In: Zlatic TD, editor. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2010. pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Dell KM, Shah SA. Evaluation of pharmacy practice residents’ research abstracts and publication rate. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(4):524–527. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robles JR, Youmans SL, Byrd DC, Polk RE. Perceived barriers to scholarship and research among pharmacy practice faculty: survey report from the AACP Scholarship/Research Faculty Development Task Force. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(1):Article 17. doi: 10.5688/aj730117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zgarrick DP. Getting Started as a Pharmacy Faculty Member. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2010. pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]