Abstract

Background

Thoracic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hygroma is a rare and potentially devastating complication of the anterior thoracic approach to the spine. We present two cases in which this complication resulted in acute cranial nerve palsy and discuss the pathoanatomy and management options in this scenario.

Case reports

Two male patients presented to our department with neurological deterioration due to a giant herniated thoracic disc. The extruded disc fragment was noted pre-operatively to be calcified in both patients. A durotomy was performed at primary disc prolapse resection in the first patient, whereas an incidental durotomy during the procedure caused complication in the second patient. These were repaired primarily or sealed with Tachosil®. Both patients re-presented with acute diplopia. Imaging of both patients confirmed a massive thoracic cerebrospinal fluid hygroma and evidence of intracranial changes in keeping with intracranial hypotension, but no obvious brain stem shift. The hemithorax was re-explored and the dural repair was revised. The first patient made a full recovery within 3 months. The second patient was managed conservatively and took 5 months for improvement in his ophthalmic symptoms.

Conclusions

The risk of CSF leakage post-dural repair into the thoracic cavity is raised due to local factors related to the chest cavity. Dural repairs can fail in the presence of an acute increase in CSF pressure, for example whilst sneezing. Intracranial hypotension can result in subsequent hygroma and possibly haematoma formation. The resultant cranial nerve palsy may be managed expectantly except in the setting of symptomatic subdural haematoma or compressive pneumocephaly.

Keywords: Thoracic disc herniation, Cerebrospinal fluid fistula, Thoracic hygroma, Complication of surgery, Acute intracranial hypotension

Case reports

A 48-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented with an 18-month history of loss of balance, paraesthesia and numbness in the lower limbs. His neurological deficit was slowly progressive and at pre-operative clinical assessment was found to have an MRC grade 4 power in his lower limbs. An MRI scan of his whole spine revealed a giant thoracic disc herniation at level T9/10, causing marked cord compression (Fig. 1). A subsequent CT scan of this level confirmed the disc to be calcified and probably adherent to, but not penetrating, the dura (Fig. 2). He underwent a discectomy via a standard mini-thoracotomy approach [1] with excision of the ninth rib. A durotomy of diameter 1.5 × 2 cm was required for complete disc excision. This was repaired in layers using an adhesive Tachosil® in two layers. Tachosil® is a synthetic collagen mesh which is activated by moisture and can be used as a watertight matrix to occlude durotomies. It has an adherent side impregnated with fibrin, which binds to tissue. In this instance, the first layer was placed inside the dural tube and the second laid adhesive side down, over the fenestration, thereby “sandwiching” the dural border between the Tachosil layers. These layers were further reinforced with fibrin glue and gelfoam overlying the patch. No CSF leak was appreciated with intraoperative Valsalva manoeuvre. A chest drain was placed post-operatively. The patient had an unremarkable initial recovery. However, 3 weeks subsequent to discharge, the patient suffered a severe coughing fit and shortly after this experienced shortness of breath and double vision. The patient re-presented with respiratory failure and a Glasgow Coma Scale of 13, confused and drowsy. He complained of severe horizontal diplopia. A diagnosis of a sixth cranial nerve (abducens nerve) palsy was evident. MRI of the cranium revealed bilateral subdural effusion (Fig. 3). A chest drain was inserted to relieve the intrathoracic compression secondary to the massive CSF hygroma, (the term hygroma refers to any fluid-filled structure and can be applied anywhere in the body). This was confirmed on an urgent MRI of whole spine and a chest CT scan (Fig. 4). Upon insertion of the chest drain, approximately 300 ml of cerebrospinal fluid was expressed into the drainage receiver. This was at no time placed under suction to avoid worsening the intracranial hypotension by promoting further cerebrospinal fluid extravasation. The diagnosis was confirmed by detecting the presence of β2 transferrin in a sample of the fluid. Revision thoracotomy and dural repair were performed as described below. His abducens nerve palsy recovered completely in 3 months following the surgery.

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic imaging (patient 1): pre-operative MRI scan showing a giant herniated disc at the T9/10 level with b marking the outline of the cord and epidural space draping the disc

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic imaging (patient 1): pre-operative CT scan showing calcification in the herniated disc

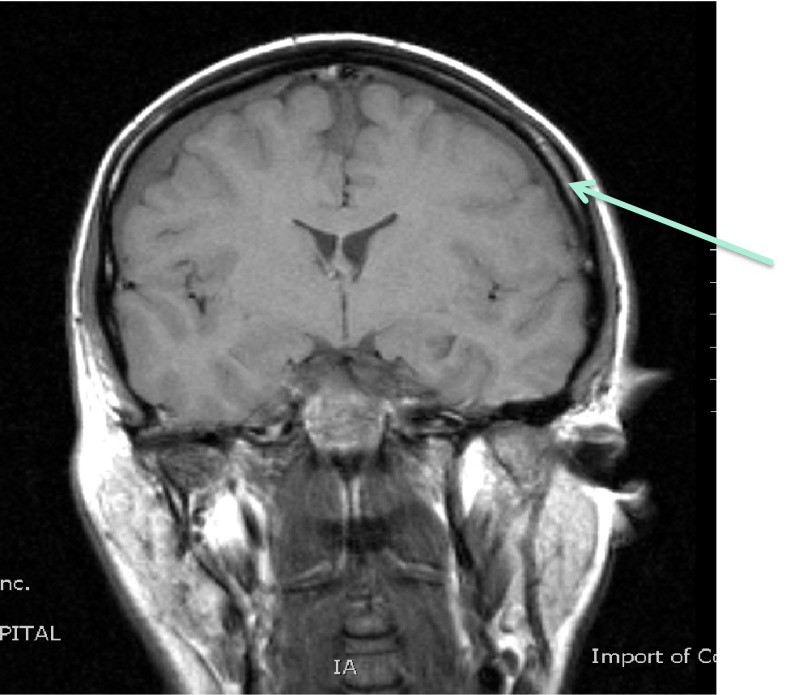

Fig. 3.

Procedure imaging section (patient 1): coronal T1-weighted image of the brain showing bilateral subdural effusions (arrowed) associated with intracranial hypotension

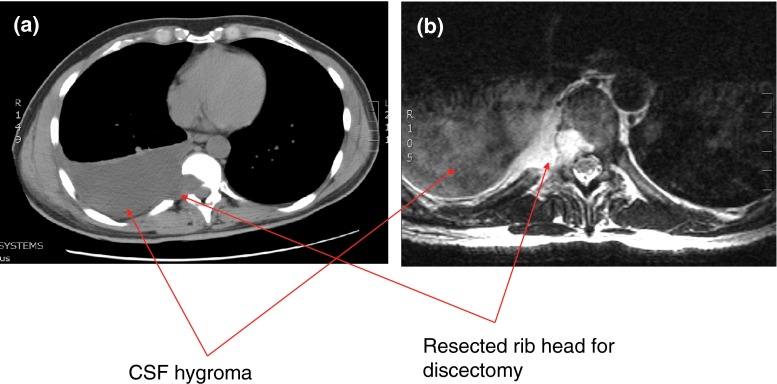

Fig. 4.

Diagnostic imaging (patient 1): CT and MRI scan showing a large intrathoracic CSF hygroma

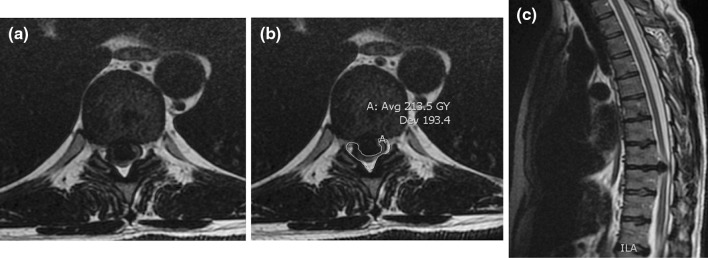

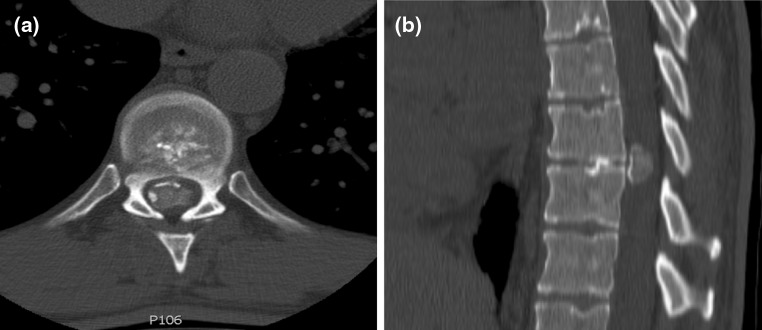

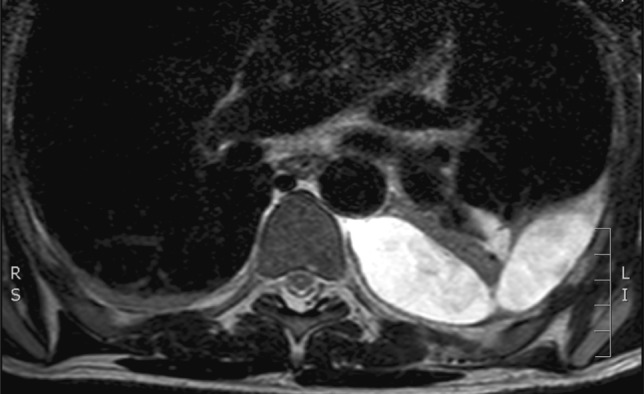

Our second case was a 46-year-old male who presented with subjective weakness in both lower limbs associated with altered sensations of several months’ duration. He had no objective neurological deficit, though his symptoms were gradually deteriorating. An MRI scan showed a giant herniated disc prolapse at T8/9 resulting in severe spinal cord compression (Fig. 5). A CT scan confirmed calcification of the herniated disc (Fig. 6). This patient underwent a left-sided thoracotomy with a hemivertebrectomy of T8 due to the extensive nature of calcification. The calcified disc was adhered to the dura and its removal resulted in an incidental durotomy. This was repaired primarily with Tachosil®. No CSF leak was appreciated with intra-operative Valsalva manoeuvre. A chest drain was placed post-operatively. Few days following the surgery, he developed diplopia due to bilateral abducens nerve palsy along with occasional headaches. An urgent MRI scan of the spine confirmed the presence of a contained CSF hygroma (Fig. 7). As his symptoms remained static, he was treated non-operatively with sequential radiological investigations to ensure that the CSF leak was not worsening. His bilateral abducens nerve palsy improved over a period of 5 months. He had a delayed T8/9 laminectomy to ensure that good posterior canal decompression was also achieved.

Fig. 5.

Diagnostic imaging (patient 2): pre-operative MRI scan showing a giant herniated disc at the T8/9 level

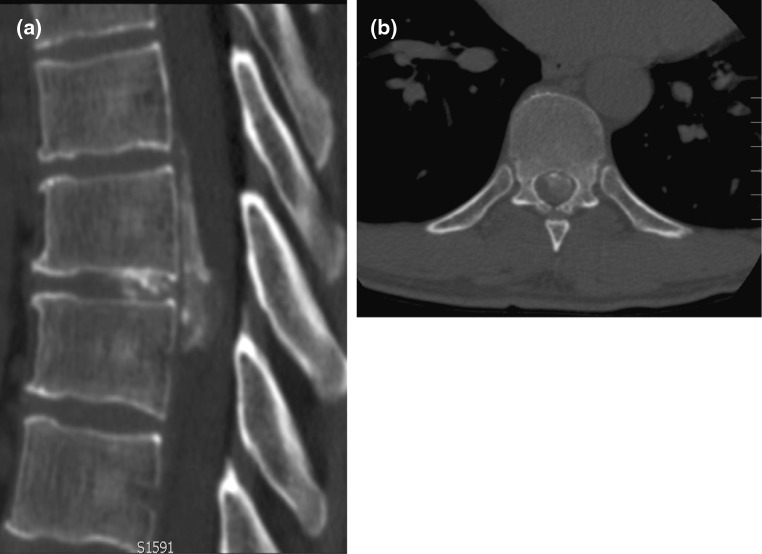

Fig. 6.

Diagnostic imaging (patient 2): pre-operative CT scan showing calcification in the herniated disc

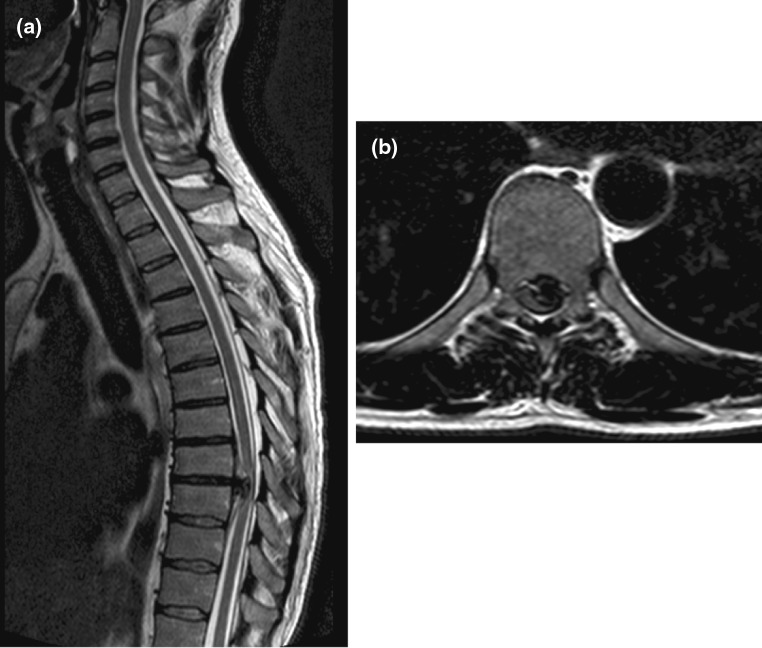

Fig. 7.

Diagnostic imaging (patient 2): post-operative MRI scan showing a large intrathoracic CSF hygroma

Introduction

Dural lesion subsequent to the anterior approach to the thoracic spine is a recognised complication and is often inevitable in the presence of a calcified disc fragment abutting the dura mater. A planned durotomy may be performed to achieve full resection. Several techniques for repair have been described, each in the context of difficult access and the inability to perform a primary repair. Subsequent massive thoracic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hygroma is a rare complication of the anterior thoracic approach to the spine. Its true incidence is unknown, but within the published literature to date less than 50 cases could be identified. The sequelae of a massive cerebrospinal fluid leakage are described and manifest with the symptoms of intracranial hypotension. These include diplopia, nausea, drowsiness, postural headache and photophobia. Latent complications include compressive pneumocephaly, bacterial meningitis and remote subdural haematoma.

Epidemiology, pathology and rationale for treatment

Symptomatic thoracic disc herniations are rare. The incidence is approximately one case per million per year [1]. Those requiring operative intervention represent an even smaller number. Of all operations performed for compressive discogenic pathologies, the thoracic region comprises only 1.8 % at most [1–4]. Hott et al. suggested a classification of herniations occupying more than 40 % of the spinal canal to be regarded as ‘giant’ [5]. It is important to derive from pre-operative imaging the degree of calcification of the extruded fragment and hence its adherence to the dura or herniation through the dura. This information guides the surgical technique required to remove the disc and allows the surgeon to predict complications such as dural tear, avoid this and utilise a planned durotomy around the lesion.

Both anterior and posterior surgical techniques have been described for the surgical management of thoracic disc herniations [1, 4–7]. The anterior approach provides good visualisation and surgical access, but carries potential morbidity associated with thoracotomy. A mini-thoracotomy with microsurgical decompression may decrease the approach-related morbidity [1, 7]. Posterior laminectomy for thoracic discectomy has been associated with unsatisfactory results since first reported by Logue [8]. However, Borm et al. argue in a recent article that a tailored posterior approach based on the anatomic location and nature of the disc along with the general health of the patient can yield satisfactory results [6]. In a prospective cohort study of 167 cases, Quint et al. conclude that thoracoscopic discectomy provides satisfactory results and can be used in calcified discs as well [9]. Cho et al. recently described a minimally invasive oblique paraspinal approach using 3-D navigation and tubular retractors with the aid of a robotic holder [10]. They do not, however, recommend this approach for a sequestrated, calcified or hard disc herniation. Similarly, the posterior transdural approach may offer an alternative surgical option for selected patients with thoracic paracentral soft discs [11]. This approach, too, is not deemed suitable for giant and calcified discs which may require extensive manipulation [11, 12].

The incidence of a massive subarachnoid-pleural fistula following anterior thoracic surgery has been described by Hentschel et al. in a series of 770 patients, with 2.8 % following anterior surgery and 0.23 % following a posterior approach [13]. This cohort represented patients in whom thoracic spine resections were undertaken for tumour pathology. No such series exist describing this complication in the post-operative group for benign discogenic disease. A review of the literature reveals 44 described cases of massive pleura-dural fistula. It can be observed that 77 % of these cases were caused by trauma of varying aetiologies and only two (4.5 %) of the cases were described as subsequent to post-operative thoracic disc resection [2, 9, 14–17]. Recently, two cases of spontaneous thoracic CSF leakage in the presence of thoracic disc hernias were described [18]. It must be concluded that subarachnoid-pleural fistula subsequent to an anterior resection of thoracic disc is a very rare entity. Massive cerebrospinal fluid leakage and subsequent intracranial hypotension have several potentially fatal consequences. Common sequelae are pneumocephaly and synchronous central nervous system infection [13, 19]. A rare clinical finding in this instance is bruit hydroaerique, wherein the patient complains of a splashing sound upon rapid movement of the head [20]. Acute meningitic infection may be managed with antibiotic chemotherapy and by addressing the dural injury that allowed entry of the pathogen.

Rarely, intracranial hypotension can result in a cerebral subdural haematoma. The mechanism of this injury is postulated as downward cerebral displacement, subsequent to CSF loss and intracerebral hypotension. This results in tension and occlusion of the superior cerebellar bridging veins, which is thought to result in venous infarction and haemorrhage [21, 22]. A review of the literature reveals only five cases of confirmed remote subdural haemorrhage subsequent to spinal surgery [16]. Two of these were subsequent to thoracic spinal surgery, while the remainder were associated with lumbar surgery. This is a rare yet significant complication that carries a mortality in the traumatic setting of up to 66 % [23].

Management of the subarachnoid-pleural fistula and subsequent thoracic CSF hygroma is dependent on the clinical presentation. The symptoms have been described above and when the diagnosis is suspected, effusive collections may be visualised primarily on a plain chest radiograph. It is then necessary to image the previous operative site. The decision must then be taken, based on the clinical findings, whether to reexplore the operative site or attempt managing the leakage with conservative means such as bed rest or divertive CSF drainage, usually distal to the fenestration. This may be augmented with repeated needle thoracocentesis and positive pressure ventilation via a noninvasive ventilator, which the patient uses at intervals during the day [24–27]. Katz et al. describe an attempt at this technique which eventually controlled leakage and allowed healing. The case was complicated by infection and symptomatic pneumocephalus [28]. A decision to adopt this conservative approach is difficult, especially when local factors (i.e. the negative pressure environment of the thorax) which antagonise the CSF leakage are considered. The thoracic cavity is by definition a negative pressure environment and hence is likely to continue to exacerbate drainage down a pressure gradient through the dural injury site. This persistent process may prevent healing and closure of the dural fenestration. Hence, a primary drainage of the presenting CSF collection via chest drain, attached to an underwater seal receiver, is often advocated. This allows decompression of the CSF hygroma and allows re-expansion of the lung into the hemithorax (a vacuum drain is contraindicated in this instance). Insertion of a drain allows sampling of the fluid collection to be performed and the diagnosis of CSF hygroma, confirmed based on the presence of β2 transferrin in the aspirate. Drainage of the primary thoracic CSF hygroma must be performed under close supervision. The average volume of CSF within the cranial vault is 150 ml. The hemithoracic cavity can easily accommodate 500 ml of fluid in the presence of ongoing negative intrathoracic pressure. There is, therefore, potential for further extravasation of fluid if the fistula is not addressed. If a conservative treatment route is adopted, the patient needs to be monitored closely, both clinically and radiologically with a provision in place for an urgent intervention in the event of any worsening.

The site of dural injury post-thoracic surgery is usually evident from the primary resection. In the first case, it originated from the formal durotomy we performed to enable resection of the extruded disc fragment. If the site of dural injury is occult, a CT myelography or radionuclide cisternography may be employed to locate the site of injury. Both have their disadvantages—the former is described with a high rate of false negatives and the latter, although more sensitive, lacks anatomical details which aid pre-operative planning [13, 29]. At re-exploration, the options for repair depend largely on the morphology of the dural injury involved. To achieve a direct repair, the described technique involves the use of synthetic collagen patches, which combined with layered fibrin glue, have been used to create a watertight seal [16]. These may be applied directly to the dura to achieve a repair of the defect. An indirect repair technique involves the purposeful formation of a contained pseudomeningocele over the defect, if local access to the dural edges is not possible for performing a repair. In this instance, the use of allo and autograft patches have been described, including allograft pleural membrane as an onlay technique over the limited anterior corpectomy [30]. This graft can then be stitched to the surrounding intact parietal pleura, creating the intentional controlled pseudomeningocele which alleviates the need to address the dural insufficiency directly. Other options include harvest of muscle [13], omentum [28], fat and fascia lata patches [30], once again in combination with fibrin glue to plug over the primary resection site. In all of these situations, except in the instance of a dural injury around a nerve root, primary repair is not usually possible.

Cranial nerve palsy is sometimes seen associated with neurological compromise subsequent to intracranial hypotension [31–33]. This complication resulting from massive thoracic cerebrospinal fluid hygroma subsequent to spinal surgery is described only once previously in the literature [34]. In this case, the cranial nerve palsy resolved spontaneously. Among the cranial nerves associated with ophthalmolplegia, the sixth cranial nerve is the most frequently involved, either unilaterally or bilaterally [31, 32] with horizontal diplopia and blurred vision [31, 32, 35]. According to the review of Zada et al. in patients with cranial nerve manifestations resulting in ocular deficits secondary to intracranial hypotension, 83 % of patients had an abducens (6th) nerve palsy, 14 % had oculomotor (3rd) nerve palsy and 7 % had trochlear (4th) nerve paresis. Abducens nerve palsy due to intracranial hypotension is a benign condition and about 80 % of patients recover spontaneously. However, if symptoms continue for 8 months or more, the possibility of permanent damage increases [33]. Previously, the abducens nerve has been suggested to be susceptible to stretch by brain displacement or traction due to its long intracranial course. More recently, a specific mechanism for the development of abducens nerve damage has been postulated [32, 35]. Anatomically, this nerve exits the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and pons, rises upward along the clivus, crosses branches of the basilar artery and pierces the dura mater. Then, the nerve sharply bends over the ridge of the petrous apex of the temporal bone. The abducens nerve runs in the same vector as that adopted during typical caudal displacement of the brain in the presence of intracranial hypotension. As a result, the force of traction associated with changes in intracranial pressure is fully transmitted to the nerve. The nerve can be stretched by downward displacement of the pons and may also be compressed at the dura, petrous apex or basilar artery if the penetration aperture for the nerve in the dura or petrous apex is sharply edged, or if branches of the basilar artery are well developed. Although there was evidence of intracranial hypotension, interestingly brain stem shift was not seen in either of our patients.

Procedure

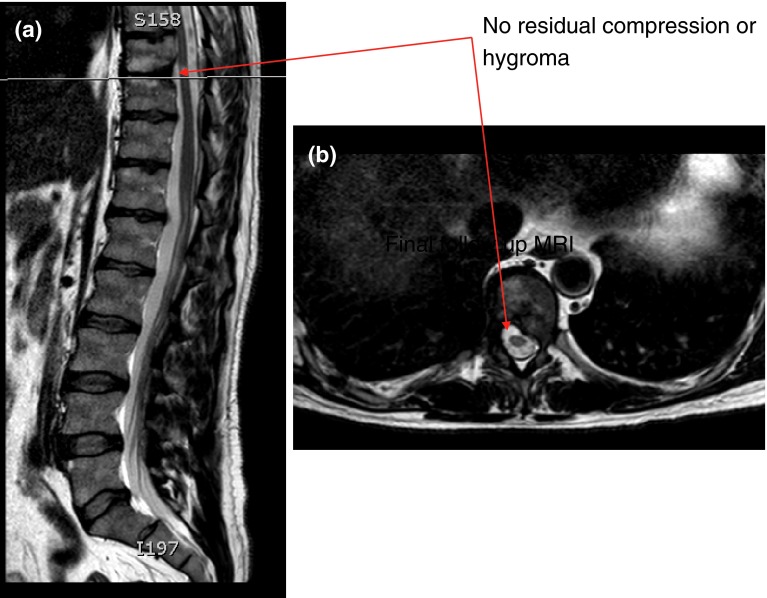

The first patient was subsequently transferred to the operating theatre and the previous operative wound site re-explored. No obvious leak was seen. The previous dural patch was revised with further application of collagen patch material and was sealed with fibrin glue. A watertight seal was confirmed on application of an intra-operative Valsalva manoeuvre. After reinflation of the lung using positive end expiratory pressure, applied via the ventilator, the wound was carefully closed in layers over a chest drain as before. An airtight seal was obtained as is routine in this procedure. Post-operatively, the patient was observed to gradually improve over a period of 72 h. During this time, his respiratory function was maintained with no artificial support and the chest drain was removed on post-operative day 3. He was discharged, fully ambulant to his own home on post-operative day 8. His abducens nerve palsy was noted to improve gradually over 3 months, as did his reported diplopia. Follow-up MRI revealed absence of spinal cord compression and hygroma (Fig. 8). The second patient was treated non-operatively with due vigilance as his psudomeningocele was contained. He had gradual improvement of his diplopia in 5 months.

Fig. 8.

Procedure imaging section (patient 1): final follow-up MRI scan showing no residual compression or hygroma

Outcome

The patient was followed up after discharge at regular intervals in the outpatient clinic. In the first patient, abducens nerve palsy was noted to have resolved fully at 3e months, whereas the second patient took 5 months for gradual improvement. The compressive neurological symptoms were also improved following the procedures to remove the calcified thoracic disc.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed to various aspects of preparation of this manuscript. There was equal contribution by Khurana A and Brousil J.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Russo A, Balamurali G, Nowicki R, Boszczyk BM. Anterior thoracic foraminotomy through mini-thoracotomy for treatment of giant thoracic disc herniations. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(2):212–220. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozgen S, Boran B, Elmaci I, Ture U, Pamir M (2000) Treatment of the subarachnoid fistula: A case report. Neurosurg Focus 9(1):ecp 1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Brown CW, Deffer PA, Akmakjian J, et al. The natural history of thoracic disc herniation. Spine. 1992;17(6):S97–S101. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199206001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick WE, Will SF, Benzel EC. Surgery for thoracic disc disease. Complication avoidance: overview and management. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(4):e13. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.4.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hott JS, Feiz-Erfan I, Kenny K, Dickman CA. Surgical management of giant herniated thoracic discs: analysis of 20 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(3):191–197. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.3.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Börm W, Bäzner U, König RW, Kretschmer T, Antoniadis G, Kandenwein J. Surgical treatment of thoracic disc herniations via tailored posterior approaches. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(10):1684–1690. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1821-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moran C, Ali Z, McEvoy L, Bolger C (2012) Mini-open retropleural transthoracic approach for the treatment of giant thoracic disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37(17):E1079–1084 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Logue V. Thoracic intervertebral disc prolapse with spinal cord compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1952;15(4):227–241. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.15.4.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quint U, Bordon G, Preissl I, Sanner C, Rosenthal D. Thoracoscopic treatment for single level symptomatic thoracic disc herniation: a prospective followed cohort study in a group of 167 consecutive cases. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(4):637–645. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2103-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho JY, Lee SH, Jang SH, Lee HY. Oblique paraspinal approach for thoracic disc herniations using tubular retractor with robotic holder: a technical note. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(12):2620–2625. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2438-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon SJ, Lee JK, Jang JW, Hur H, Lee JH, Kim SH. The transdural approach for thoracic disc herniations: a technical note. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(7):1206–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppes MH, Bakker NA, Metzemaekers JD, Groen RJ. Posterior transdural discectomy: a new approach for the removal of a central thoracic disc herniation. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(4):623–628. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1990-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hentschel SJ, Rhines LD, Wong FC, Gokaslan ZL, McCutcheon IE. Subarachnoid fistula after resection of thoracic tumours. J Neurol. 2004;100(4 Suppl):332–336. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.4.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raffa SJ, Benglis DM, Levi AD. Treatment of a persistent iatrogenic cerebrospinal fluid-pleural fistula with a cadaveric dural-pleural graft. Spine J. 2009;9(4):e25–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizuno J, Mummaneni PV, Rodts GE, Barrow DL. Recurrent subdural haematoma caused by cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:183–185. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung YY, Ju C, Kim SW. Bilateral subdural haematoma due to an unnoticed dural tear during spine surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;47:316–318. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.47.4.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd C, Sahn SA. Subarachnoid pleural fistula due to penetrating trauma: case report and review of the literature. Chest. 2002;122:2252–2256. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasiloglu ZI, Abuzayed B, Imal AE, Cagil E, Albayram S. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension due to intradural thoracic osteophyte with superimposed disc herniation: report of two cases. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl 4):S383–S386. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1828-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assietti R, Kibble MB, Bakay M, Salcman AE, Batzdorf U. Iatrogenic cerebrospinal fluid fistula to the pleural cavity: case report and literature review. Neurosurgery. 1993;6:1104–1108. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199312000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown WM, 3rd, Symbas PN. Pneumocephalus complicating routine thoracotomy: symptoms, diagnosis and management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59(1):234–236. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)00434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadduck WM. Cerebellar haemorrhage complicating cervical laminectomy. Neurosurgery. 1981;9(2):185–189. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladehoff M, Zachow C. Cerebellar haemorrhage and tension pneumocephalus after resection of a Pancoast tumour. Acta Neurochir. 2005;147(5):561–564. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0402-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilberger JE, Harris M, Diamond D. Acute subdural haematoma: morbidity, mortality and operative timing. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(2):212–218. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.2.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samandouras G, Bajtajic V, Cross F, Hamlyn P. Cranial sudural hygroma complicating thoracic surgery. JBJS Br. 2004;84 A:2033–2037. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salerni AA, KuivillaTE Drvaric DM. Traumatic subarachnoid pleural fistula in a child. A case report. Clin Orthop. 1991;264:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyunoya T, Gross T, Rooney C, Mendoza S, Kline J. Massive pleural transudate following a vertebral fusion in a 4 year old woman. Chest. 2003;123:1280–1283. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eismont F, Wiesel S, Rothman R. Treatment of dural tears associated with spine surgery. JBJS. 1981;63A:1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz SS, Savitz MH, Osei C, Harris L. Successful treatment of lumboperitoneal shunting of a spinal subclavicular fistula following thoracotomy. Neurosurgery. 1982;11(6):795–796. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez P, Guyot M, Mangione P, Valli N, Basse-Cathalinat B, Ducassou D. Subarachnoid pleural fistula complicating thoracoscopy: value of In-111DTPA myeloscintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 1999;24(2):985–986. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199912000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamji MF, Sundaresan S, Da Silva V, Seely J, Shamji FM. Subarachnoid-pleural fistula: applied anatomy of the thoracic spinal nerve root. ISRN Surg. 2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/168959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zada G, Solomon TC, Giannotta SL. A review of ocular manifestations in intracranial hypotension. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E8. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/11/E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishio I, Williams BA, Williams JP. Diplopia: a complication of dural puncture. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:158–164. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200401000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koeppen AH. Abducens palsy after lumbar puncture. Proc Wkly Semin Neurol. 1967;17(2):68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashok T, Ajoy PS, Rajasekaran S. Abducens nerve palsy associated with pseudomeningocele after lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 2011;37(8):E511–E513. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182373b95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schober P, Loer SA, Schwarte LA. Paresis of cranial nerve VI (N. abducens) after thoracic dural perforation. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76(12):1085–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]