Abstract

Objective

To assess the costs associated with the provision of services for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of human immunodeficiency virus in two African countries.

Methods

In 2009, the costs to health-care providers of providing comprehensive PMTCT services were assessed in 20 public health facilities in Namibia and Rwanda. Information on prices and on the total amount of each service provided was collected at the national level. The costs of maternal testing and counselling, male partner testing, CD4+ T-lymphocyte (CD4+ cell) counts, antiretroviral prophylaxis and treatment, community-based activities, contraception for 2 years postpartum and early infant diagnosis were estimated in United States dollars (US$).

Findings

The estimated costs to the providers of PMTCT, for each mother–infant pair, were US$ 202.75–1029.55 in Namibia and US$ 94.14–342.35 in Rwanda. These costs varied with the drug regimen employed. At 2009 coverage levels, the maximal estimates of the national costs of PMTCT were US$ 3.15 million in Namibia and US$ 7.04 million in Rwanda (or < US$ 0.75 per capita in both countries). Adult testing and counselling accounted for the highest proportions of the national costs (37% and 74% in Namibia and Rwanda, respectively), followed by management and supervision. Treatment and prophylaxis accounted for less than 20% of the costs of PMTCT in both study countries.

Conclusion

The costs involved in the PMTCT of HIV varied widely between study countries and in accordance with the protocols used. However, since per-capita costs were relatively low, the scaling up of PMTCT services in Namibia and Rwanda should be possible.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer les coûts associés à la prestation de services pour la prévention de la transmission mère-enfant (PTME) du virus de l'immunodéficience humaine dans deux pays africains.

Méthodes

En 2009, les coûts pour les prestataires de soins liés à l'offre de services complets de PTME ont été évalués dans 20 établissements de santé publics en Namibie et au Rwanda. Des informations sur les prix et sur le montant total de chaque service fourni ont été recueillies au niveau national. Les coûts des conseils fournis et des tests réalisés par les mères, des dépistages des partenaires masculins, des comptages des lymphocytes-T CD4+ (cellules CD4+), de la prophylaxie et du traitement antirétroviral ou encore des activités communautaires, de la contraception pendant 2 ans après l'accouchement et du diagnostic précoce des nourrissons ont été estimés en dollars.

Résultats

Les coûts pour les prestataires de PTME, pour chaque couple mère-enfant, ont été estimés à 202,75-1029,55 dollars en Namibie et à 94,14-342,35 dollars au Rwanda. Ces coûts variaient selon le protocole médicamenteux utilisé. Au niveau de la couverture atteinte en 2009, les coûts nationaux maximum de la PTME ont été estimés à 3,15 millions de dollars en Namibie et à 7,04 millions de dollars au Rwanda (soit < 0,75 dollars par habitant dans les deux pays). Les conseils fournis et les tests réalisés par les adultes ont représenté la plus grande proportion des coûts nationaux (37% et 74% en Namibie et au Rwanda, respectivement), suivis du traitement médical et de la surveillance. Le traitement et la prophylaxie ont représenté moins de 20% des coûts de la PTME dans les deux pays étudiés.

Conclusion

Les coûts liés à la PTME du VIH ont varié considérablement d'un pays étudié à l'autre et selon les protocoles utilisés. Toutefois, étant donné que les coûts par habitant ont été relativement faibles, l'intensification des services de PTME en Namibie et au Rwanda devrait être possible.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar los costes asociados con la prestación de servicios para la prevención de la transmisión maternofilial del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana en dos países africanos.

Métodos

En el año 2009 se evaluaron los costes de los proveedores de atención sanitaria que prestaban servicios completos de prevención de la transmisión maternofilial en 20 centros sanitarios públicos en Namibia y Rwanda. La información sobre los precios y sobre la cantidad total de cada servicio prestado se recogió a nivel nacional. Los costes de las pruebas y el asesoramiento materno, las pruebas para las parejas masculinas, los recuentos de linfocitos T CD4+ (células CD4+), el tratamiento y profilaxis antirretrovirales, las actividades comunitarias, los anticonceptivos durante 2 años después del parto y el diagnóstico precoz de lactantes se calcularon en dólares americanos (US$).

Resultados

Para cada par madre-hijo, los costes estimados de los proveedores de servicios para prevenir la transmisión maternofilial fueron de US$ 202,75–1029,55 en Namibia y US$ 94,14–342,35 en Rwanda. Estos costes variaron según la terapia empleada. En los niveles de cobertura del 2009, las estimaciones máximas de los costes nacionales de la prevención de la transmisión maternofilial fueron de US$ 3,15 millones en Namibia y US$ 7,04 millones en Rwanda (o < US$ 0,75 per cápita en ambos países). Las pruebas y el asesoramiento de adultos representaron la mayor parte de los costes nacionales (37% en Namibia y 74% en Rwanda), seguidos por la gestión y la supervisión. El tratamiento y la profilaxis significaron menos del 20% de los costes de la prevención de la transmisión maternofilial en ambos países.

Conclusión

Los costes implicados en la prevención de la transmisión maternofilial del VIH variaron mucho entre los países de estudio y según los protocolos empleados. Sin embargo, puesto que los costes per cápita fueron relativamente bajos, sí sería posible ampliar los servicios de prevención de la transmisión maternofilial tanto en Namibia como el Rwanda.

ملخص

الغرض

تقييم التكاليف المرتبطة بتقديم الخدمات من أجل الوقاية من انتقال فيروس العوز المناعي البشري من الأم إلى الطفل (PMTCT) في بلدين أفريقيين.

الطريقة

في عام 2009، تم تقييم التكاليف التي يتكبدها مقدمو الرعاية الصحية في تقديم خدمات الوقاية من انتقال العدوى من الأم إلى الطفل في 20 مرفقاً صحياً عمومياً في ناميبيا ورواندا. وتم جمع المعلومات الخاصة بالأسعار وبالمبلغ الإجمالي لكل خدمة مقدمة على الصعيد الوطني. وتم تقدير تكاليف فحوصات الأمومة وإسداء المشورة والفحوصات التي تجرى على الشريك الذكر وإحصاء الخلايا اللمفاوية التائية المساعدة (CD4+) والوقاية والعلاج بمضادات الفيروسات القهقرية والأنشطة المجتمعية واستعمال وسائل منع الحمل لمدة سنتين بعد الوضع والتشخيص المبكر للرضع بالدولار الأمريكي.

النتائج

بلغت التكاليف التي تكبدها مقدمو خدمات الوقاية من انتقال فيروس العوز المناعي البشري من الأم إلى الطفل عن كل أم ورضيعها وفق التقديرات ما بين 202.75 إلى 1029.55 دولاراً أمريكياً في ناميبيا وما بين 94.14 إلى 342.35 دولاراً أمريكياً في رواندا. واختلفت هذه التكاليف باختلاف النظام الدوائي المستخدم. وعلى مستويات التغطية في عام 2009، بلغت أقصى تقديرات للتكاليف الوطنية للوقاية من انتقال العدوى من الأم إلى الطفل 3.15 مليون دولار أمريكي في ناميبيا و7.04 مليون دولار أمريكي في رواندا (أو أكثر من 0.75 دولاراً أمريكياً للفرد في كلا البلدين). وتُعزى أعلى نسب التكاليف الوطنية (37 % و74 % في ناميبيا ورواندا، على التوالي) إلى فحوصات البالغين وإسداء المشورة، يليها التدبير العلاجي والإشراف. ويُعزى أقل من 20 % من تكاليف الوقاية من انتقال العدوى من الأم إلى الطفل في كلا بلدي الدراسة إلى العلاج والوقاية.

الاستنتاج

اختلفت تكاليف الوقاية من انتقال فيروس العوز المناعي البشري من الأم إلى الطفل على نحو واسع بين بلدي الدراسة وحسب البروتوكولات المستخدمة. ولكن نظراً للانخفاض النسبي في التكاليف لكل فرد، ينبغي أن يكون تعجيل خدمات الوقاية من الانتقال العدوى من الأم إلى الطفل في ناميبيا ورواندا أمراً ممكناً.

摘要

目的

评估两?非洲国家提供预防母婴艾滋病毒传播(PMTCT)服务的相关成本。

方法

2009 年,对纳米比亚和卢旺达20 个公共卫生设施中卫生保健提供者提供全面PMTCT服务的成本进行评估。在国家层面上收集所提供每项服务的价格信息和合计金额。孕产妇检测和咨询、男性伴侣检测、CD4+T淋巴细胞(CD4+细胞)计数、抗逆转?病毒预防和治疗、社区活动、产后2 年避孕和婴儿早期诊?的成本以美元估计。

结果

纳米比亚每对母婴PMTCT的提供者的估计成本在是202.75-1029.55 美元,卢旺达是94.14-342.35 美元。这些成本因采用的用药方案而异。在2009 年的覆盖率水平下,PMTCT的最高估计成本在纳米比亚是315 万美元,在卢旺达是704 万美元(或两个国家人均都< 0.75 美元)。成人检测和咨询在全国成本中所占的比例最高(纳米比亚为37%,卢旺达?74%),其次是管理和监督。在这?个研究国家中,治疗和预防仅占PMTCT不到20%的成本比率。

结论

HIV的PMTCT所涉及的成本被研究国家之间差异很大,并与所使用的方案一致。然而,由于人均成本相对?低,在纳米比亚和卢旺达?大PMTCT服务规模应?是可能的。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить расходы, связанные с предоставлением услуги по профилактике передачи ВИЧ инфекции от матери к ребенку (ППВМР) в двух африканских странах.

Методы

В 2009 году проведена оценка расходов медицинских учреждений, предоставляющих комплексные услуги по ППВМР, в 20 учреждениях общественного здравоохранения Намибии и Руанды. Сбор информации по ценам и общей стоимости каждой предоставляемой услуги проводился на национальном уровне. Стоимость проведения консультации и анализа на ВИЧ у матерей, анализа на ВИЧ у партнеров (мужчин), показателя числа CD4+ Т-лимфоцитов (CD4+ клеток), профилактики и лечения антиретровирусными препаратами, предоставления услуг по месту жительства, противозачаточных мероприятий в течении двух лет после родов и ранняя диагностика у детей оценивалась в долларах США.

Результаты

Подсчитанные расходы медицинских учреждений, предоставляющих услуги по ППВМР, из расчета на каждую пару мать-ребенок, составили 202,75–1029,55 долларов США в Намибии и 94,14–342,35 долларов США в Руанде. Эти расходы варьируются в зависимости от используемой схемы приема лекарственных средств. Исходя из величины покрытия в 2009 году, максимальная оценка расходов по ППВМР составила 3,15 миллионов долларов США в Намибии и 7,04 миллионов долларов США в Руанде (или < 0,75 на душу населения в обеих странах). На проведение консультаций и анализов на ВИЧ у взрослых приходится наибольшая доля государственных расходов (37% и 74% в Намибии и Руанде, соответственно), за которыми следуют лечение и наблюдение. На лечение и профилактику приходится менее 20% всех расходов на ППВМР в обеих странах.

Вывод

Расходы на услуги по профилактике передачи ВИЧ инфекции от матери к ребенку широко варьируются в исследованных странах и в зависимости от программы действий. Однако так как стоимость услуг на душу населения была относительно низкой, расширение масштабов предоставления услуг по ППВМР в Намибии и Руанде представляется возможным.

Introduction

It has been estimated that 330 000 children became infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 2011 and that most of these children lived in sub-Saharan Africa, where access to interventions for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV remains uneven and generally poor.1 Although one main goal of the maternal, neonatal and child health services that operate in sub-Saharan Africa is to achieve an HIV-free generation, sustained efforts and huge commitment will be required to reach this goal, given the severe limitations on health expenditure in the region.2–4 The countries of sub-Saharan Africa already spend a mean of 19% of their total health expenditures on HIV-related activities but, unfortunately, those total expenditures are extremely low. In a study of 30 countries, they were estimated to be less than 21 United States dollars (US$) per capita.5,6 The prevention and control of HIV infection in such countries are also heavily dependent on external funding7 that may not be sustainable in the long term.8–10

If investment in efforts to eliminate new HIV infections among children by 201511 is to be increased, further data on the costs of PMTCT interventions must be collected. This study aimed to collect accurate and reliable data on the costs and affordability of the provision of PMTCT services in Namibia and Rwanda.

Methods

Country selection and site sampling

Namibia and Rwanda were chosen for study because, although their epidemics of HIV infection were of similar magnitude, the two countries had different levels of PMTCT service coverage. In 2009, antiretroviral coverage among HIV-infected pregnant women in Namibia (88%) exceeded the threshold set for “universal” coverage (80%), whereas the corresponding coverage in Rwanda (65%) fell well below this threshold.12,13 In each of the two study countries, 10 health facilities were chosen at random for detailed investigation from among those public facilities that appeared to be delivering a comprehensive range of maternal, neonatal and child health services at the lowest level of the health pyramid (i.e. 105 primary health centres in Rwanda and 34 regional hospitals in Namibia).

Study design

The study followed a three-tiered approach. First, the costs of the routine delivery of PMTCT services to pregnant women or to mothers and HIV-exposed infants were calculated using a “micro-costing” or “ingredient-based” method in which costs were estimated by identifying the resources used for each “patient”. The value of the resources or “ingredients” was then estimated from the relevant quantities and corresponding unit prices, as described by Drummond et al.14 Second, in each study country, the estimated costs per woman–infant pair and records of the numbers of such pairs provided with PMTCT services nationally were used to generate an estimate of the total national cost of PMTCT services. Third, the affordability of the national PMTCT programme in each study country was assessed by estimating the per-capita costs for specific types of users of the PMTCT services and for the entire population.

Perspective and costing methods

All costs were estimated from the perspective of the providers of the PMTCT services. Estimates were based on the operating costs incurred by the providers and on any relevant donated items (e.g. credit for the mobile phones used to track patients who would otherwise have been lost to follow-up, which was financed by implementing partners). All costs were converted from local currencies into US$ using the mean conversion rates for 2009 (i.e. US$ 1 = 571 Rwandan francs and 7.4 Namibian dollars). Information on prices was collected, at the national level, from government and international partners. At the time of the study, the users of PMTCT services in Namibia and Rwanda were not charged. Any indirect costs to users or their families, such as transportation costs, and any capital costs associated with the services, were ignored. Costs incurred over more than 1 year were discounted at 3% per year.

Service package components

Costs were estimated for each of the seven major components of the PMTCT services provided in the study countries: HIV testing and counselling of pregnant women and, where applicable, their male partners; CD4+ cell counts (for treatment eligibility and treatment monitoring); provision of antiretroviral drugs to the mother–infant pairs (for both prophylaxis and treatment); community-based activities; provision of oral contraception for 2 years postpartum; prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole (a combination of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim) for HIV-exposed infants aged 6 weeks to 2 years, and early infant diagnosis. The only community-based activities taken into consideration were those found to be common in the two study countries (i.e. telephone calls and home-based visits); rarer activities (e.g. monthly support meetings and income generation) were ignored.

Unit costs

In a standardized framework involving three sets of information, the cost of each major component of the PMTCT services was estimated as Y = W + C + D, where W, C and D represent the relevant costs of the human workforce involved, the commodities used and the drugs prescribed (if any), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Components of the unit costs of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009.

| Activity | Cost components |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce | Commodities | Drugs | |

| Testing and counselling | Midwife, physician | Rapid test kit, ELISA, miscellaneous items | None |

| CD4+ cell counts | Midwife, laboratory technician, driver | Reagent, miscellaneous items | None |

| Provision of antiretrovirals | Midwife, physician | None | Antiretroviralsa |

| Community-based activities | Social worker | Transportation fare | None |

| SXTb prophylaxis | Nurse, social worker | None | SXTb |

| Family planning | Midwife, social worker | None | Oral contraceptives |

| Early infant diagnosis | Nurse, laboratory technician, driver | Reagent, miscellaneous items | None |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SXT, co-trimoxazole.

a Single-dose nevirapine, two- and three-drug combinations for prophylaxis, the antiretroviral therapy recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2006,15 or Options A or B recommended by WHO in 2010.16

b In paediatric and/or adult formulations.

Costs associated with antiretroviral provision were estimated per mother–infant pair. The prophylactic and treatment regimens considered were those in use in Namibia and Rwanda at the time of the study (Table 2). They differed widely in terms of the drugs used and the duration of their use – from single-dose nevirapine to various combinations of antiretroviral drugs for prophylaxis and as part of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for eligible pregnant women or mothers. The costs associated with the Option A and Option B prophylactic regimens recommended for pregnant women by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 201016 were also estimated, even though these recommendations had not been published at the time of the present study. The Namibian Ministry of Health has recently decided to use Option A prophylaxis, whereas the Rwandan Ministry of Health is now promoting the tenofovir-based Option B, but either country may shift from one option to the other in the future.17 In Namibia and Rwanda, as elsewhere, ART is only currently ensured for eligible pregnant women and mothers.

Table 2. Antiretroviral regimens for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009.

| Regimen | Pregnant women |

Mothers | Infants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepartum | Intrapartum | |||

| NVP | None | SD-NVP | None | NVP (either SD at birth or nothing) |

| 2 antiretrovirals for PMTCT prophylaxis | ZDV (as early as week 28) | NVP | ZDV/3TC (until 7 days postpartum) | SD-NVP at birth + ZDV (up to 1 or 4 weeks of age) |

| 3 antiretrovirals for PMTCT prophylaxis | ZDV/3TC/NVP (as early as week 28) | ZDV/3TC/NVP | ZDV/3TC (until 7 days postpartum) | SD-NVP at birth + ZDV (up to 1 or 4 weeks of age) |

| 2006 WHO ART recommendations15 | ZDV/3TC/NVPa | ZDV/3TC/NVPa | ZDV/3TC/NVPa | SD-NVP at birth + ZDV (up to 1 or 4 weeks of age) |

| 2010 WHO ART recommendations16 | ||||

| Option A | ZDV (as early as week 14) | ZDV/3TC/NVP | ZDV/3TC (until 7 days postpartum) | NVP (to end of BF + 1 week) |

| Option B | TDF/3TC/EFVb | TDF/3TC/EFVb | TDF/3TC/EFVb | NVP (up to 4–6 weeks of age) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; BF, breastfeeding; EFV, efavirenz; NVP, nevirapine; SD, single-dose; 3TC, lamivudine; TDF, tenofovir; WHO, World Health Organization; ZDV, zidovudine.

a As early as week 28 of gestation to 12 months postpartum (i.e. end of recommended BF).15

b As early as week 14 of gestation to 12 months postpartum (i.e. end of recommended BF) plus 1 week.

If more than one option existed for delivering a given PMTCT-related activity, only the most expensive option was used for the cost estimates. For instance, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis can be provided through either paediatric or adult formulations but, for settings where both formulations were available, we only estimated the costs associated with the provision of the more expensive, paediatric formulation.

National costs

For each study country, the estimated unit costs of each service component (e.g. the costs per mother–infant pair) were multiplied by published estimates18 of the numbers of individuals receiving each component nationally, to generate estimates of the corresponding national costs. The national estimates were therefore based on actual costs accrued rather than on available or budgeted resources.

National estimates were made using the numbers of pregnant women who were tested, male partners who were tested as part of PMTCT activities, HIV-infected pregnant women who were assessed for ART eligibility, and HIV-infected pregnant women or mothers who were receiving prophylaxis for PMTCT of HIV. The number of HIV-infected pregnant women or mothers receiving ART was also used, but only after adjustments had been made to take into account both the duration of breastfeeding and losses to follow-up in the course of treatment. Following the latest review on patient retention in ART programmes in sub-Saharan Africa, we assumed a retention rate at 12 months of 80.2%.19 As death was estimated to represent 41% of the attrition rate,19 we assumed that only 59% of the women lost to follow-up could be put back on ART via home-based visits. The costs of CD4+ cell counts for each woman on ART, after 6 and 12 months of breastfeeding, were included in the national estimates. The model used to generate the national estimates also took into account the numbers of HIV-exposed infants (i.e. those born to HIV-infected mothers) who were given antiretroviral prophylaxis at birth or who initiated co-trimoxazole prophylaxis within 2 months of birth. The number of HIV-infected mothers who received oral contraceptives for 2 years postpartum was used as a proxy for the number of infants on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis. In estimating the national costs of PMTCT services, the costs of early infant diagnosis were excluded because such diagnosis was considered to be the first step in paediatric HIV care and treatment rather than an element of the PMTCT programmes.

Expenditures related to the management and supervision of PMTCT services – the costs of routine PMTCT-related meetings at the health-facility level, the salaries of the individuals who supervised PMTCT services at the health-facility level, the salaries of the individuals who worked for the implementing partners or government office in charge of PMTCT services nationally, and the costs of holding PMTCT-related training sessions – were included in the national estimates.

Affordability

The estimated costs of the PMTCT programmes in Namibia and Rwanda, at the coverage levels seen in 2009, were considered in relation to each of several measures of programme performance: the number of paediatric HIV infections prevented (derived from data provided by the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates Modelling and Projections20), the number of HIV-infected pregnant women or mothers who received antiretroviral prophylaxis and treatment, the number of mother–infant pairs that received prophylaxis (including co-trimoxazole for HIV-exposed infants and antiretroviral drugs), the number of pregnant women who received HIV testing and counselling, and the overall number of individuals (women, male partners and infants) reached by the programme. Finally, for each study country, the cost per capita (based on the national population) of the PMTCT programme was estimated and converted to a percentage of the total health expenditure per capita.

Data collection

Teams of data collectors and team supervisors obtained data from the 20 study facilities over a two-week period in October and November 2009. Team supervisors included representatives from national authorities, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Bordeaux University. Data collectors included trained nurses and physicians from the public health sector of the country in which the data were being collected. International consultants, along with UNICEF country office staff, trained the data collectors. The training included an overview of costing methods, an in-depth review of the survey tools and practical exercises. A “time-and-motion” approach was used to document the PMTCT-related activities performed at each study facility. A national consultant helped oversee the fieldwork, collected national-level data over the following 3 weeks and resolved inconsistencies. Data on the salaries of physicians, laboratory technicians, nurses, midwives, social workers and staff involved in health administration were obtained from the relevant national authorities. Monthly earnings – including bonuses, overtime and any performance-based financing payments – were converted to hourly rates according to the official number of hours to be worked, per month, by health personnel in each study country. Data on the prices of HIV screening tests, antiretroviral drugs and other miscellaneous items – syringes, gloves, test tubes, etc. – were collected from national centres for medical supplies. The costs of transporting such items from national supply centres to the health facilities where the items were to be used and the cost of subsequent storage were taken to be equivalent to 10% of the prices paid at the supply centres. Expenditure data were obtained from implementing partners through face-to-face interviews or from expenditure-tracking reports.

Results

Unit costs

Table 3 summarizes the unit cost estimates associated with each PMTCT-related activity. Namibia had generally higher unit costs than Rwanda, attributable mainly to higher health personnel salaries.

Table 3. Maximum estimated unit costs of activities pertaining to the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009.

| Activity | Cost (US$)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Namibia | Rwanda | |

| Testing and counselling | 21.56 | 9.99 |

| CD4+ cell count | 17.03 | 11.17 |

| Treatment and prophylaxis | ||

| NVP | 1.54 | 0.18 |

| 2 antiretrovirals for PMTCT prophylaxis | 25.62 | 63.91 |

| 3 antiretrovirals for PMTCT prophylaxis | 92.76 | 32.68 |

| 2006 WHO ART recommendations15 | 483.83 | 165.61 |

| 2010 WHO ART recommendations16 | ||

| Option A | 326.70 | 136.69 |

| Option B | 766.78 | 203.33 |

| SXT prophylaxis for the HIV-exposed infant | 48.11 | 16.64 |

| Family planning | 113.67 | 34.53 |

| Early infant diagnosis | 60.92 | 10.91 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NVP, nevirapine; SXT, co-trimoxazole; US$, United States dollars; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Depending on the activity, the costs shown are per mother–infant pair, per woman, per individual or per infant.

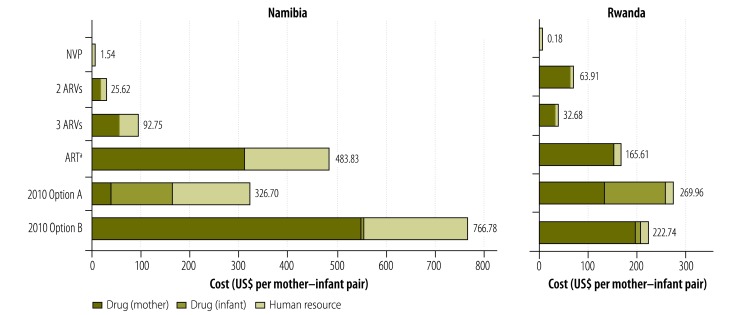

The estimated costs of providing antiretrovirals to each mother–infant pair ranged from less than US$ 1.00 for single-dose nevirapine in Rwanda to approximately US$ 750 for the Option B regimen in Namibia (Fig. 1). The estimated costs of antiretroviral drugs were higher in Namibia (US$ 1.54–759.67 per mother–infant pair) than in Rwanda (US$ 0.18–203.33), with the sole exception of the two-drug antiretroviral combination used for prophylaxis (Table 3). On average, human resources accounted for 34% of the costs of antiretroviral drug provision in Namibia but for only 4% of such costs in Rwanda (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Estimated unit costs of antiretroviral provision, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009

ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; NVP, nevirapine; US$, United States dollars.

a As early as week 28 of gestation to 12 months postpartum.15

Note: 2010 Options A and B represent the drug regimens recommended by the World Health Organization in 2010.16

The maximum estimated per-patient cost of HIV testing and counselling was more than twice as high in Namibia (US$ 21.56) as in Rwanda (US$ 9.99) (Table 3). Similarly, the unit costs of early infant diagnosis, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and contraceptive provision were 3- to 6-fold higher in Namibia than in Rwanda.

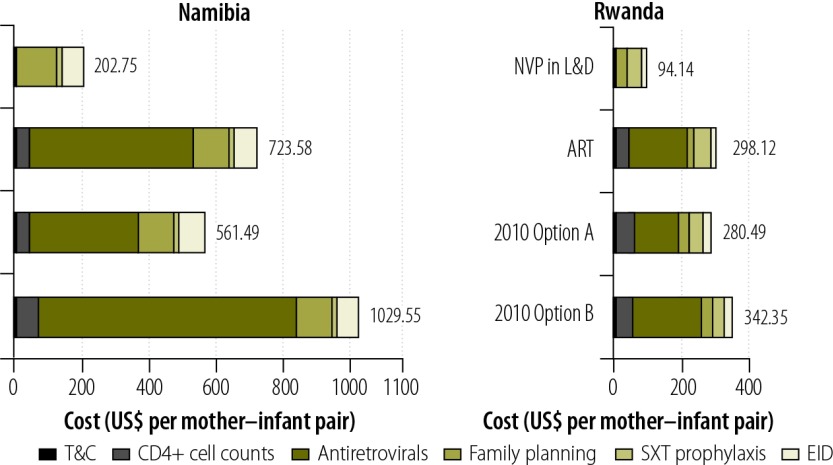

Fig. 2 gives the estimated total costs of all PMTCT services, per mother–infant pair, according to the antiretroviral regimen assumed to be in use. The regimen assumed to be in use had a marked effect on these costs. Under the same conditions, in 2009 in Rwanda, Options A and B would have cost 6% less and 15% more per mother–infant pair, respectively, than the ART regimen recommended by WHO in 2006;15 in 2009 in Namibia, Options A and B would have cost 29% less and 42% more per mother–infant pair, respectively, than the ART regimen recommended in 2006.

Fig. 2.

Estimated total costs, per mother-infant pair, of all regimens and services for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009

ART, antiretroviral therapy; EID, early infant diagnosis; L&D, labour and delivery; NVP, nevirapine; SXT, co-trimoxazole; T&C, testing and counselling; US$, United States dollars.

a As early as week 28 of gestation to 12 months postpartum.15

Note: 2010 Options A and B represent the drug regimens recommended by the World Health Organization in 2010.16

In all modelled scenarios except for those involving single-dose nevirapine, antiretroviral prophylaxis accounted for the largest proportion of the unit costs of PMTCT services (Fig. 2). On average, the costs of providing antiretrovirals accounted for 66% of total unit costs in Namibia and for 55% of such costs in Rwanda. In each study country, this proportion would drop to 1% or less if the antiretroviral regimen in use for the PMTCT of HIV were restricted to single-dose nevirapine.

The total estimated costs of PMTCT services included the estimated costs of an initial CD4+ cell count to determine ART eligibility and of subsequent counts needed to monitor treatment. CD4+ cell counts accounted, on average, for 6% and 15% of the total estimated costs of PMTCT services in Namibia and Rwanda, respectively.

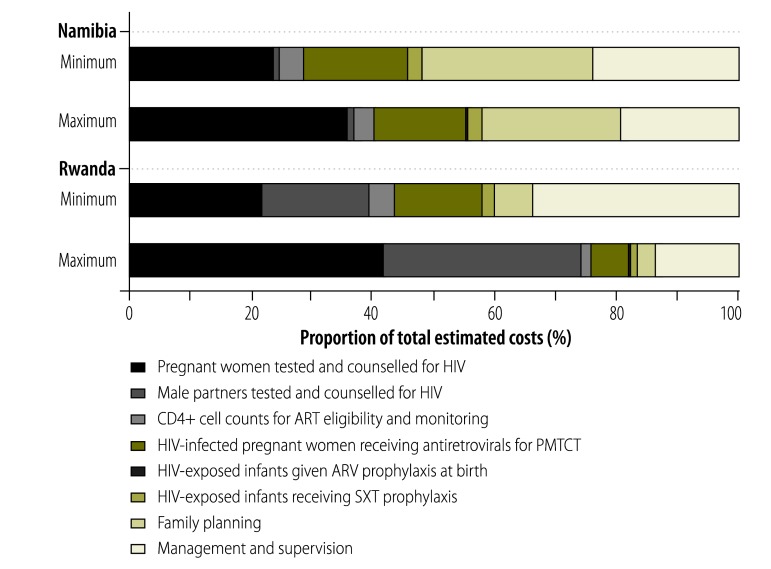

National estimates

For 2009, national estimates of the costs of PMTCT services ranged from US$ 2.57 million to US$ 3.15 million in Namibia and from US$ 2.83 million to US$ 7.04 million in Rwanda. Of the main PMTCT-related services that were considered, HIV testing and counselling accounted for the largest proportions of the estimated national costs (25–37% and 39–74% of the totals in Namibia and Rwanda, respectively; Fig. 3), followed by management and supervision (19–24% and 14–34% of the totals in Namibia and Rwanda, respectively). Unexpectedly, the costs of providing antiretroviral drugs to HIV-infected pregnant women/mothers accounted for relatively small proportions of the estimated total national costs of PMTCT services in both Namibia and Rwanda (15–17% and 6–14%, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Components of the total estimated costs of the national programmes for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009

ART, antiretroviral therapy;a ARV, antiretroviral; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SXT, co-trimoxazole.

a As early as week 28 of gestation to 12 months postpartum;15

Note: Proportions are shown for both the minimum and maximum estimated total costs for each country.

Affordability

At 2009 coverage levels, the costs per HIV infection averted were generally lower in Namibia (US$ 2050–2515) than in Rwanda (US$ 1909–4738). However, the costs per individual reached by the national PMTCT programme were much lower in Rwanda (US$ 5–13) than in Namibia (US$ 46–57). In both countries, the cost of the PMTCT programme per inhabitant was less than US$ 0.75 (Table 4).

Table 4. Cost estimates for national programmes for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, Namibia and Rwanda, 2009.

| Cost | Range of estimates (US$) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Namibia | Rwanda | |

| Per paediatric HIV infection averted | 2050–2515 | 1909–4738 |

| Per HIV-infected pregnant woman reached | 344–422 | 394–979 |

| Per mother–infant pair reached | 292–356 | 226–836 |

| Per pregnant woman reached | 49–60 | 10–24 |

| Per person reached | 46–57 | 5–13 |

| Per inhabitant of the country | 0.26–0.32 | 0.28–0.70 |

| Total national cost | 2 570 475–3 153 270 | 2 838 706–7 038 892 |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; US$, United States dollars.

Discussion

When this study was launched, published data on the costs of providing PMTCT services in resource-limited settings in general, and in sub-Saharan Africa in particular, were very scarce.21–23 Furthermore, it was unclear if the wide cost variations that had been reported were the result of differences in practice, price differentials and/or costing methods. In the present study, comparable information was collected from two countries by applying a consistent definition for the PMTCT-service “package” and using identical methods for data collection and analysis. The micro-costing methods that were followed also helped to provide accurate and detailed estimates of the cost structures pertaining to PMTCT services in each study country.

Some of the differences observed between Namibia and Rwanda in unit cost estimates reflect differences in the way in which PMTCT services are provided and/or in the PMTCT algorithms in use. For example, the health centres studied in Rwanda lacked the capacity to perform CD4+ cell counts. Blood samples had to be transported to other facilities and this generated transport costs. On the other hand, the health centres studied in Namibia were all regional hospitals equipped to perform CD4+ cell counts “in house”.

In general, the costs of PMTCT per mother–infant pair varied substantially with the study country and the antiretroviral regimen in use or assumed to be in use. Estimates of such costs were highest in Namibia, owing largely to better remuneration of the health personnel than in Rwanda. Even when performance-based financing payments were included, the estimated mean hourly incomes of Rwandan physicians and nurses/midwives in 2009 appeared extremely low (US$ 2.67 and US$ 1.23, respectively) and much lower than their Namibian equivalents (US$ 43.62 and US$ 10.57, respectively).

In attempts to determine all of the expenses associated with PMTCT services, costs need to be broken down by task. The cost of the same antiretroviral drugs can vary widely by country. This needs to be considered when the recommendations in international guidelines, such as those that have recently introduced the antiviral regimens known as Options A and B,24 are tailored to suit a particular country.

According to our estimates, in 2009, the national PMTCT programme in Rwanda cost twice as much as the corresponding Namibian programme. The costs of prophylaxis were not a major component of the total costs of the PMTCT programme in either country, even after infant prophylaxis and co-trimoxazole provision were taken into account. Instead, HIV testing and counselling represented the largest share of the national costs, partly because in Rwanda these services are offered to pregnant women and their male partners rather than to pregnant women only. At the time of the present study, mean coverage of male partners with HIV testing and counselling was approximately 84% in the Rwandan PMTCT programme, as opposed to merely 10% in sub-Saharan Africa as a whole.18,25 Rwanda’s attempt to reach all pregnant women’s male partners should be viewed as a model rather than an exception. It allows the early referral of HIV-positive men to the Rwandan programme for HIV care and encourages HIV-negative men to follow strategies for the prevention of HIV infection.

At the levels of coverage seen in 2009, both of the national PMTCT programmes investigated cost no more than US$ 0.75 per inhabitant. PMTCT services took up a very small proportion of total health expenditure in both Rwanda (1.27–3.18%) and Namibia (0.17–0.21%) in 2009 and appeared to represent good value for the money spent on them. However, current uncertainty regarding long-term investment in HIV prevention and care should not be underestimated.8–10 Most industrialized countries are experiencing an economic downturn that is expected to substantially reduce the overseas aid they provide.26

The present study has several limitations. First, the objective was to cost the components of a defined package of PMTCT interventions. Hence, we ignored certain activities that support PMTCT but that fall outside the sphere of national PMTCT programmes, such as the primary prevention of HIV infection among women of reproductive age. However, we did account for the reduction of unintended pregnancies in HIV-infected women owing to the provision of oral contraception for 2 years postpartum.27–29 Second, because we restricted costing methods to operating costs only, our estimates cannot be easily compared with values from the few relevant studies that have included capital costs. Third, to estimate national costs we multiplied unit costs by the reported numbers of individuals using particular PMTCT services in each country. We were unable to assess the accuracy of the reported numbers, most of which came from a WHO review18 rather than directly from the Namibian and Rwandan governments. The value for PMTCT service coverage reported for Côte d’Ivoire, in the same WHO review (41%)18 was found to be much higher than the corresponding value derived from national survey data (18%).30,31 Fourth, the health facilities selected for detailed investigation were obtained from a list of facilities that provided a comprehensive range of PMTCT services. Our national costs may therefore be over-estimates, as they were determined on the assumption that all individuals reached by the national PMTCT programmes only attended facilities that provided such a range of services. Despite these limitations, our cost estimates appear reasonable and are similar to the corresponding estimates made elsewhere. In Nigeria, for example, the cost of providing tenofovir–lamivudine–efavirenz beginning on week 14 of gestation was estimated to be US$ 401 per pregnancy.22 This estimate fits within the cost range for similar treatment in the present study (US$ 350–1000).

In summary, this paper provides detailed and up-to-date information on the costs of PMTCT-related services in two countries of sub-Saharan Africa. Such information is needed to estimate the additional resources needed to scale up PMTCT services within the context of the Millennium Development Goals. It should also help resource-limited countries, external funders and multilateral agencies to plan activities and identify cost drivers and areas of potential savings in their attempts to reach the global goal of eliminating paediatric HIV infection by 2015.

Funding:

This work was supported through funding from the HIV Section, UNICEF, New York. Between 2009 and 2011, HT was a fellow of the French charity SIDACTION. Funding sources played no role in the design of the study, analysis of the data or interpretation of the results.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012 Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2012. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 2.65/277 Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS: intensifying our efforts to eliminate HIV/AIDS New York: United Nations; 2011. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2011/06/20110610_UN_A-RES-65-277_en.pdfhttp://[accessed 20 January 2013].

- 3.Cavagnero E, Daelmans B, Gupta N, Scherpbier R, Shankar A, Countdown Working Group on Health Policy and Health Systems Assessment of the health system and policy environment as a critical complement to tracking intervention coverage for maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet. 2008;371:1284–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, Berman P, Boerma T, Bryce J, et al. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet. 2010;375:2032–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amico P, Aran C, Avila C. HIV spending as a share of total health expenditure: an analysis of regional variation in a multi-country study. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirigia JM, Preker A, Carrin G, Mwikisa C, Diarra-Nama AJ. An overview of health financing patterns and the way forward in the WHO African Region. East Afr Med J. 2006;83:S1–28. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v83i9.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izazola-Licea JA, Wiegelmann J, Arán C, Guthrie T, De Lay P, Avila-Figueroa C. Financing the response to HIV in low-income and middle-income countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(Suppl 2):S119–26. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181baeeda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The global economic crisis and HIV prevention and treatment programmes: vulnerabilities and impact Washington: World Bank; 2009. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTHIVAIDS/Resources/375798-1103037153392/TheGlobalEconomicCrisisandHIVfinalJune30.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 9.The Global Fund: a bleak future ahead. Lancet. 2010;376:1274. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mugyenyi P. Flat-line funding for PEPFAR: a recipe for chaos. Lancet. 2009;374:292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global plan towards the elimination of new infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive, 2011–2015 Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2011. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/20110609_jc2137_global-plan-elimination-hiv-children_en-1.pdfhttp://[accessed 20 January 2013].

- 12.Republic of Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) country report; reporting period 2008–2009 Windhoek: Directorate of Special Programmes, Division Expanded National HIV/AIDS Coordination; 2010. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/namibia_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 13.Republic of Rwanda. United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV and AIDS: country progress report January 2008 – December 2009 Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2010. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/rwanda_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 14.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants in resource-limited settings: towards universal access, recommendations for a public health approach Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/pmtct/en/index.html [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 16.Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: recommendations for a public health approach, 2010 version Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599818_eng.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013]. [PubMed]

- 17.Bachman G, Phelps BR. PMTCT and community: updates & PEPFAR perspectives Toronto: Coalition for Children Affected by AIDS; 2012. Available from: http://www.ccaba.org/wp-content/uploads/Bachman-and-Phelps-presentation.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 18.Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. progress report, 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/tuapr_2009_en.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 19.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [Internet]. Spectrum/EPP 2011. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/datatools/spectrumepp2011/ [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 21.Desmond C, Franklin L, Steinberg M. The prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission: costing the service in four sites in South Africa Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2004. Available from: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/PMTCT_Costing.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 22.Shah M, Johns B, Abimiku A, Walker DG. Cost-effectiveness of new WHO recommendations for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a resource-limited setting. AIDS. 2011;25:1093–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMennamin T, Fellow A, Fritsche G. Cost and revenue analysis in six Rwandan health centers: 2005 cost and revenues Cambridge: Management Sciences for Health; 2007. Available from: http://erc.msh.org/toolkit/toolkitfiles/file/Rwanda_Core_Plus_Final_Report.pdf [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 24.Programmatic update: use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants, executive summary, April 2012 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/programmatic_update2012/en/index.html [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 25.Irakoze A, Nsanziman S, Mababazi J, Remera E, Nsabimana G, Tsague L et al. Uptake of HIV testing in pregnant women and their male partners in Rwanda PMTCT program Jan 2005–June 2011 16th International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa; 2011 4–8 Dec; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Available from: http://www.icasa2011addis.org [accessed 20 January 2013].

- 26.Ventelou B, Arrighi Y, Greener R, Lamontagne E, Carrieri P, Moatti JP. The macroeconomic consequences of renouncing to universal access to antiretroviral treatment for HIV in Africa: a micro-simulation model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petruney T, Robinson E, Reynolds H, Wilcher R, Cates W. Contraception is the best kept secret for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.051458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duerr A, Hurst S, Kourtis AP, Rutenberg N, Jamieson DJ. Integrating family planning and prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2005;366:261–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66917-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds HW, Janowitz B, Wilcher R, Cates W. Contraception to prevent HIV-positive births: current contribution and potential cost savings in PEPFAR countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(Suppl 2):ii49–53. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stringer EM, Ekouevi DK, Coetzee D, Tih PM, Creek TL, Stinson K, et al. PEARL Study Team Coverage of nevirapine-based services to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in 4 African countries. JAMA. 2010;304:293–302. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coffie PA, Kanhon SK, Touré H, Ettiegne-Traoré V, Stringer E, Stringer JS, et al. Nevirapine for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a nation-wide coverage survey in Côte d’Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821ea539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]