Abstract

This is the first study contrasting regional glucose metabolic rate (rCMRglu) responses to a serotonergic challenge in major depressive disorder (MDD) with and without comorbid alcohol dependence. In a university hospital, patients with MDD without a history of alcohol dependence (MDD only) and patients with MDD and comorbid alcohol dependence (MDD/ALC) were enrolled in this study. Subjects with comorbid borderline personality disorder were excluded. A bolus injection of approximately 5 mCi of 18fluorodeoxyglucose was administered 3 h after the administration of placebo or fenfluramine. We found an anterior medial prefrontal cortical area where MDD/ALC subjects had more severe hypofrontality than MDD only patients. This area encompassed the left medial frontal and left and right anterior cingulate gyri. This group difference disappeared after fenfluramine administration. The fact that the observed group difference disappeared after the fenfluramine challenge suggests that serotonergic mechanisms play a role in the observed differences between the groups.

Keywords: Depression, Alcohol dependence, Fenfluramine, Serotonin, Positron emission tomography

1. Introduction

Major depression and alcohol dependence (alcoholism) are often comorbid (Buydens-Branch et al., 1989; Cornelius et al., 1995, 1996; Davidson and Blackburn, 1998; Gilman and Abraham, 2001; Herz et al., 1990; McGrath et al., 2000; O’Sullivan et al., 1988; Roy et al., 1991a,b; Schuckit, 1986; Spak et al., 2000; Thase et al., 2001). The prevalence in the United States of a lifetime history of major depression is 5% in men and 19% in women who have alcoholism (Helzer and Pryzbeck, 1988; Regier et al., 1990; Schuckit and Winokur, 1972). Some prevalence rates are higher, according to the National Comorbidity Study (Kessler et al., 1997), over 32% of those surveyed with alcoholism also had a lifetime history of major depression. High prevalence rates of depression have also been reported in clinical samples of alcoholism. Miller et al. (1996) reported that 43.7% of over 6000 patients in addiction treatment reported a lifetime prevalence of depression. A recent study suggests that a median prevalence of current or lifetime alcohol problems in depression is 16% and 30%, respectively (Sullivan et al., 2005). Depressed subjects with alcoholism have more chronic impairment and more suicidal behavior than individuals with either diagnosis alone (Cornelius et al., 1995, 1996; O’Sullivan et al., 1988; Sher et al., 2003a, 2005; Thase et al., 2001).

The serotonergic system is involved in the pathophysiology of both depression and alcoholism (Fromme and D’Amico, 1999; Mann et al., 1999; Ratsma et al., 2002; Sher and Mann, 2003). Brain imaging positron emission tomography (PET) studies have used fenfluramine challenge to map regional serotonergic function based on regional glucose metabolic rate (rCMRglu) responses (Anderson et al., 2004; Mann et al., 1996a,b; Newman et al., 1998; Siever et al., 1999; Oquendo et al., 2003b, 2005; Ratsma et al., 2002). Previous PET studies that used fenfluamine administration demonstrated that psychopathology is associated with abnormal rCMRglu responses (Siever et al., 1999; Oquendo et al., 2003b; Anderson et al., 2004; Oquendo et al., 2005).

Fenfluramine causes a release of serotonin and regional brain metabolic responses to release of serotonin can be measured by 18fluorodeoxyglucose and PET. The time to peak concentration after a fenfluramine administration is between 2 and 4 h (Campbell and Turner, 1971). The hormonal response to the serotonin releasing agent/uptake inhibitor fenfluramine has been widely used as an indicator of central serotonin system function in humans (Mann et al., 1996a,b; Newman et al., 1998; Sher et al., 2003b). Fenfluramine acts both presynaptically to increase serotonin release and postsynaptically as a receptor agonist. Because of these dual properties, challenge tests using fenfluramine provide an overall indication of the ‘net’ activity of the serotonergic system, in contrast to other challenge agents where the information which can be derived is limited to an assessment either of serotonin release or of activity at one of the many types of postsynaptic receptors for serotonin. Because the serotonergic system is involved in the etiopathogenesis of both depression and alcoholism, the fenfluramine administration is an important research tool in research on depressive and alcohol use disorders.

To compare serotonin function in alcoholism and major depression we sought to map regional brain differences in serotonin responsiveness in MDD with and without comorbid alcoholism. It has been demonstrated that subjects with comorbid MDD and borderline personality disorder (BPD) have significant differences in the patterns of rCMRglu pathology compared to MDD patients without BPD (Oquendo et al., 2005). Therefore, we have excluded BPD patients from the study sample.

We hypothesized that metabolic activity in the prefrontal cortex would be blunted in MDD patients with comorbid alcoholism compared with MDD patients without a history of alcoholism. To our knowledge, this is the first such study of this kind.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Patients were recruited through advertising and referrals and admitted to a university hospital for participation in mood disorders research. All subjects gave written informed consent as required by the Institutional Review Board for Biomedical Research. Eighteen MDD patients without a history of alcoholism (MDD only) and 8 MDD patients with comorbid alcoholism (MDD/ALC) participated in the study. Some of these cases have been previously reported (Oquendo et al., 2005). All subjects met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for a current major depressive episode. Patients had to be free from prescribed medications known to affect brain serotonin, dopamine, or norepinephrine systems for a minimum of 14 days. The drug-free interval was longer for drugs with a long half-life (6 weeks for fluoxetine and 4 weeks for oral antipsychotics). Among psychotropics, small doses of short-acting benzodiazepines were permitted but had to be discontinued 72 h before the PETstudy. Patients were free from alcohol or drug abuse/dependence for at least 2 months. The duration of the substance abuse free status of the patients was established by a combination of urine and blood toxicological screenings, observation in the hospital, and a history obtained from the patient, the patient’s family and the referring physician. Seven MDD/ALC and 13 MDD only patients were treated as inpatients. Patients with high levels of suicidality were managed as inpatients during the medication-free state. Five MDD/ALC and 4 MDD only patients were tobacco smokers. There were no patients with psychotic symptoms among study participants. Subjects with BPD were excluded from the study sample. All subjects were free of medical illness, based on history, physical examination and laboratory tests including liver function tests, hematologic profile, thyroid function tests, urinalysis and toxicology.

2.2. Clinical evaluation

DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview I (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview II (SCID-II), respectively, for DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Current severity of depression was assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton, 1960) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1961). Lifetime aggression and hostility were assessed with the Aggression History Scale (Brown-Goodwin, revised) (Brown and Goodwin, 1986) and Buss-Durkee Hostility Scale (Buss and Durkee, 1957), respectively. Current hopelessness was measured with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck et al., 1974b). The Reasons for Living Inventory was used to assess possible protective factors against suicide attempts (Linehan et al., 1983). Current suicidal ideation was measured by the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (Beck et al., 1979). A lifetime history of all suicide attempts, including number of attempts and the method for each attempt, was recorded on the Columbia Suicide History Form (Oquendo et al., 2003a). A lethality scale was used to measure the degree of medical damage caused by each suicide attempt (Beck et al., 1975). The scale was scored from 0 to 8 (0 = no medical damage, 8 = death), with different anchor points for various suicide attempt methods. A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act committed with some intent to end one’s life. The degree of suicide intent was rated with the Suicide Intent Scale (Beck et al., 1974a). Further details regarding the patient assessment can be found in our previously published description of research instruments (Oquendo et al., 2003a).

2.3. Fenfluramine administration

Subjects had been studied on two consecutive days after fasting and not smoking from midnight and throughout the challenge test. They received placebo on the first day and fenfluramine on the second in a single blind design. At 8 AM, on each study day, an intravenous catheter was inserted and a solution of 5% dextrose and 0.45% saline was infused. An oral dose of approximately 0.8 mg/kg of fenfluramine (or identical pills containing placebo) was administered at 9:00 AM. Fenfluramine was always given on the second day to avoid enduring pharmacological effects. Blood samples were drawn 15 min before capsule administration, at the time of administration of the capsule and then hourly for 5 h. Prolactin response to fenfluramine administration was defined as follows: the maximum prolactin level during hours 2 through 5 minus the baseline prolactin level. Baseline was defined as the mean of the prolactin values at three time points: −15 min, 0, and 1 h. We elected to use these three time points to establish a baseline because the process of accommodation of prolactin levels to the insertion of the intravenous catheter sometimes took more than 1 h, such that hour 1 prolactin levels were occasionally lower than time 0 prolactin levels. Prolactin responses to fenfluramine administration and fenfluramine+norfenfluramine levels in the two diagnostic groups were compared using t-test.

2.4. Positron emission tomography studies

PET studies were performed on both days. In order to capture the maximal response to fenfluramine, a bolus injection of approximately 5 mCi 18FDG was administered 3 h after the administration of placebo/fenfluramine. Subjects gazed at a uniform visual stimulus (crosshairs) in a dimmed room during the first 15 min of the 18FDG distribution phase. Subjects were then transferred to the scanner where they lay supine. A custom made thermoplastic mask was used to minimize head movement. The head was positioned so that the lowest scanning plane was parallel to the canthomeatal line and approximately 1.0 cm above it, at that point the laser crosshair positions on the mask were marked. For the second study, the head was positioned as closely as possible to the first study by using the original mask and the laser light marks from the previous study. A Siemens ECAT EXACT 47 scanner (in plane spatial resolution 5.8 mm, axial resolution 4.3 mm FWHM at center) was used to acquire a 60-min emission scan in 3D mode as a series of twelve 5-min frames. The attenuation correction was based on a 15-min 68Ge/68Ga transmission scan. Images were reconstructed with a Shepp radial filter, cutoff frequency of 35 cycles per projection rays and a ramp axial filter, cutoff frequency of 0.5 S.

Regions of significant differences in rCMRglu between MDD only and MDD/ALC subjects on placebo day and fenfluramine day were evaluated using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM), Version 99 (SPM99; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) (Friston, 1995). Automated image coregistration (Woods et al., 1992) was used to align the 12 frames within each study (Mann et al., 1996a,b). The resulting summed image was transformed into MNI standard stereotaxic atlas space. Each image was smoothed by applying an isotropic Gaussian kernel to increase the signal to noise ratio. Proportional scaling was applied within each condition controlling for global CMRglu. For each group, the adjusted mean rCMRglu and variance were computed at each voxel for both placebo day and fenfluramine day. These were used to perform a t-test and p values (uncorrected and corrected for multiple comparisons) were computed for the differences of the means between groups for each study day at each voxel. A whole brain parametric map was constructed based on t values displaying all voxels with p<0.01 (Friston, 1995).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, clinical, and physiological data

Demographic and clinical characteristics of MDD/ALC and MDD only patients are presented in Table 1. MDD only patients had lower aggression (p=0.003) scale scores and tended to have lower hostility (p = 0.07) scale scores compared to MDD/ALC subjects. There were no other differences in demographic or clinical features between the two groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of depressed patients with and without comorbid alcoholism

| Variable | Depressed patients without comorbid alcoholism |

Depressed patients with comorbid alcoholism |

Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (N) | SD (%) | Mean (N) | SD (%) | df | t (χ2) | P | |

| Demographic | |||||||

| Age (years) | 41.44 | 13.84 | 44.88 | 15.05 | 24 | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| Gender (% male) | (10) | (55.6) | (5) | (62.3) | 1 | (0.10) | 0.74 |

| Marital status (% married) | (4) | (22.2) | (1) | (12.5) | 1 | (0.34) | 0.56 |

| Education (years) | 15.56 | 3.42 | 15.38 | 3.30 | 24 | −1.26 | 0.91 |

| Body weight (kg) | 79.80 | 16.63 | 74.80 | 12.44 | 24 | 0.76 | 0.46 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.85 | 4.70 | 25.26 | 2.01 | 24 | −0.91 | 0.37 |

| Clinical assessment | |||||||

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | 21.67 | 3.93 | 22.88 | 3.40 | 24 | 0.75 | 0.46 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 31.78 | 8.04 | 34.00 | 11.98 | 24 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Beck Hopelessness Inventory | 12.94 | 4.62 | 12.25 | 3.95 | 24 | −0.37 | 0.72 |

| Brown–Goodwin Aggression Scale | 14.94 | 3.94 | 22.25 | 7.53 | 24 | 3.27 | 0.003 |

| Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory | 31.71 | 10.60 | 40.25 | 10.38 | 23 | 1.89 | 0.07 |

| Course of illness | |||||||

| Number of previous hospitalizations | 2.06 | 3.41 | 1.29 | 1.11 | 24 | −0.58 | 0.59 |

| Number of previous depressive episodes | 3.56 | 2.33 | 3.38 | 2.13 | 24 | −0.19 | 0.85 |

| Age at first hospitalization | 32.85 | 14.47 | 36.00 | 13.54 | 18 | 0.48 | 0.64 |

| Age of first major depressive episode | 28.44 | 16.34 | 26.38 | 14.98 | 24 | −0.30 | 0.76 |

| Age of onset of heavy drinking (years) | 23.83 | 3.97 | |||||

| Time between onset of heavy drinking and participation in the study (years) |

28.17 | 12.67 | |||||

| Trauma experience | |||||||

| Childhood abuse | (6) | (33.3) | (2) | (25.0) | 1 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Suicidal behavior | |||||||

| Suicide attempt status | (8) | (44.4) | (2) | (25.0) | 1 | (0.89) | 0.34 |

| Number of previous suicide attempts in attempters |

3.38 | 4.78 | 1.5 | 0.71 | 8 | −0.53 | 0.61 |

| Suicide intent at the time of the most lethal attempt |

18.12 | 4.32 | 23.50 | 0.71 | 8 | 1.68 | 0.13 |

| Maximum lethality of suicide attempts | 4.38 | 2.00 | 6.00 | 1.41 | 8 | 1.10 | 0.32 |

Prolactin levels rose significantly after fenfluramine was administered compared to prolactin levels after placebo administration (p < 0.001) but there was no statistically significant difference in prolactin responses to fenfluramine administration or in maximum fenfluramine+norfenfluramine levels between the two groups.

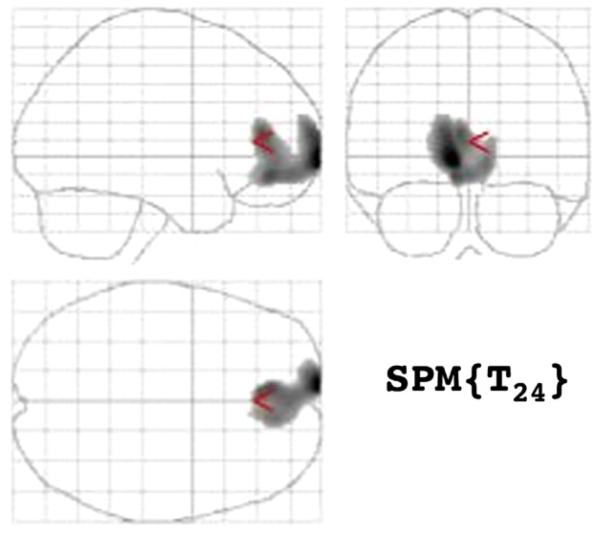

3.2. rCMRglu in MDD with or without a history of alcoholism

Comparing rCMRglu after placebo and fenfluramine administration between MDD only and MDD/AUD patients, we found after placebo a large (cluster size 1912) anterior medial prefrontal cortex area (Fig. 1) where MDD/AUD patients had more severe hypofrontality than MDD only patients. This area encompassed the left medial frontal (BA 10) and left and right anterior cingulate gyri (BA 32). This group difference disappeared after fenfluramine administration.

Figure 1.

Areas of greater relative regional cerebral metabolis, rate for glucose (rCMRglu) in depressed subjects without comorbid alcohol dependence compared to depressed subjects with comorbid alcohol dependence.

| Extent of Cluster P (voxels, Z) |

Voxel height corrected p (Z) |

(x, y, z) coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| 0.013 (1912, 3.41) | 0.794 (3.41) | −8, 70, −2 |

| 0.989 (2.98) | −8, 44, −10 | |

| 0.993 (2.94) | −4, 40, 10 | |

| 0.998 (2.83) | −2, 54, −10 | |

| 0.999 (2.77) | 10, 46, −4 |

4. Discussion

We found higher aggression and hostility in depressed subjects with comorbid alcoholism compared to their non-alcoholic counterparts. We also found a higher hypofrontality in MDD/ALC compared to MDD only patients. The administration of fenfluramine eliminated this difference.

4.1. PFC in depression and alcoholism

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that abnormalities in the PFC are associated with major depression and alcoholism (Drevets, 2000; Mayberg et al., 2000; Milak et al., 2005; Peterson et al., 1990; Phillips et al., 2003; Volkow and Fowler, 2000). In our study, both patient groups consisted of subjects with major depressive episode in the context of major depressive disorder. Therefore, the observed differences in the metabolic activity may be attributed to the fact that one group of subjects had comorbid alcoholism while their counterparts did not. Indeed, reduced glucose utilization in the orbitofrontal/ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex has been observed in detoxified alcoholics (Volkow and Fowler, 2000). The literature suggests that alcohol’s most pronounced effects appear to be on cognitive abilities associated with the prefrontal cortex (Peterson et al., 1990; Arbuckle et al., 1994; Fuster, 1997; Lyvers and Maltzman, 1991; Sayette et al., 1994; Bush et al., 2000; Carter et al., 1998). In an early study, alcohol significantly impaired tests associated with prefrontal cortex, had a less pronounced effect on tests associated with temporal cortex and did not appear to impair performance on standard intelligence tests (Peterson et al., 1990). Subsequently, a variety of studies have been conducted which demonstrate alcohol’s specific interference with cognitive capacities thought to be mediated by the prefrontal cortex, including attention, abstract reasoning, abstraction, and working memory (Arbuckle et al., 1994; Fuster, 1997; Lyvers and Maltzman, 1991; Sayette et al., 1994). Dysfunction of the medial prefrontal cortex interferes with conflict monitoring (Bush et al., 2000; Carter et al., 1998), a task that may be especially important in individuals with alcoholism who decide to remain abstinent despite alcohol craving. PFC abnormalities may be one of the mechanisms that make abstinence so difficult in many cases.

4.2. Serotonin, depression, and alcoholism

In our study, the observed differences in the metabolic activity in the PFC disappeared after the administration of fenfluramine, a serotonin releasing agent/uptake inhibitor. This suggests that higher hypofrontality in MDD/ALC subjects may be related to serotonergic abnormalities or may be correctable or effectively treated by enhancement of serotonergic activity.

Serotonergic mechanisms are involved in the mechanisms of depression and alcohol misuse (Agren and Reibring, 1994; Doudet et al., 1995; Enoch et al., 2003; Heinz et al., 1998, 2002; Messa et al., 2003; Neumeister, 2003; Sher and Mann, 2003). In the PFC, the density of serotonin transporters and 5-HT2A receptors is highest in the anterior cingulate and adjacent medial PFC (BA32, 33, 24, 11, 10 and medial BA9) (Rosel et al., 2002). In patients suffering from major depression, PET studies with the radioligand 11C-5-HTP suggested that tracer uptake in the medial PFC cortex may mirror an increased synthesis of serotonin in this brain area (Agren and Reibring, 1994). In accordance with this hypothesis, a PET study observed that serotonin 5-HT2 receptors were down-regulated in the frontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex of drug-naïve patients suffering from major depression, but did not differ from normal control values in euthymic patients who had responded to SSRI medication (Messa et al., 2003).

Studies suggest that central serotonin turnover is regulated by the medial prefrontal cortex (Juckel et al., 1999). Glucose utilization in the PFC, especially the orbitofrontal cortex, is inversely correlated with CSF 5-HIAA concentrations in a non-human primate model of excessive alcohol intake (Doudet et al., 1995). Low glucose utilization in the medial PFC and high CSF 5-HIAA concentrations are correlated with high levels of depression in detoxified male alcoholics (Williams et al., 2004). A voxel-based analysis showed that within the medial PFC, the negative correlation between CSF 5-HIAA and glucose metabolism was strongest in the left orbitofrontal and ventromedial PFC. Another study demonstrated that in subjects with alcoholism, severity of depression was associated with low serotonin availability in the raphe area and high concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA in CSF (Heinz et al., 2002). A significant reduction (a mean of about 30%) in the availability of brainstem serotonin transporters was found in patients with alcoholism, which was significantly correlated with lifetime alcohol consumption and with ratings of depression and anxiety during withdrawal (Heinz et al., 1998). It is possible, that individuals with comorbid MDD and alcoholism use alcohol to “restore” the serotonergic balance and to improve metabolic activity in the PFC. Indeed, acute alcohol intake has been associated with increased levels of serotonin and its metabolite 5-HIAA, suggesting increased serotonergic release or turnover, respectively (LeMarquand et al., 1994). The idea that alcohol use “restores” the serotonin balance is consistent with our findings.

Low doses of alcohol activate the 5-HT3 receptor (Lovinger and White, 1991; Samson and Harris, 1992) which, in turn, increases dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Jiang et al., 1990). This dynamic association between serotonergic activity and dopamine release provides a potential modulatory mechanism for the reinforcing effects of alcohol (LeMarquand et al., 1994; Nevo and Hamon, 1995).

Treatment response to SSRIs was associated with an increase in glucose metabolism in the medial, ventrolateral and dorsolateral areas of the PFC and with a decrease in metabolism in the (subgenual) cingulate and insula (Buchsbaum et al., 1997; Kennedy et al., 2001; Mayberg et al., 2000). This is consistent with our observation that the administration of fenfluramine abolishes the difference between the groups. This is also consistent with the observations suggesting that serotonergic antidepressants have a significant effect on comorbid depressive symptoms regardless of whether alcoholism is a primary or secondary disorder (Thase et al., 2001; Cornelius et al., 2004; Sher, 2006). The SSRIs have become the antidepressants of first choice for depressed patients with alcoholism because they are more readily prescribed at therapeutic doses, better tolerated by an average patient, and much safer in overdose. The high suicide risk of depressed patients with alcoholism makes the safety in overdose a compelling strength. Some patients with alcoholism may be less tolerant to side effects of SSRIs compared with depressed patients without comorbid alcoholism (Thase et al., 2001).

We have observed higher aggressiveness and hostility in the depressed group with comorbid alcoholism compared to the other group. It is commonly proposed that lower serotonin activity is tied to increased aggression/impulsivity (Verona and Patrick, 2000), which in turn is presumed to enhance the probability of suicidal behavior (Mann et al., 1999, 2001). A number of studies identified abnormalities of the serotonin system in prefrontal cortex in suicide victims (Mann et al., 1996a,b; Stanley and Mann, 1983; Stanley et al., 1982). There are fewer presynaptic serotonin transporter sites in the prefrontal cortex of suicide completers. Autoradiographic studies of prefrontal cortex in suicide victims localize this abnormality to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Arango et al., 1995). This effect is related to suicide and is independent of a history of major depression (Mann et al., 2000). Reduced serotonin input in the PFC may underlie decreased behavioral inhibition in individuals with alcoholism and a greater probability of acting on suicidal feelings. This may be one of the mechanisms that contribute to higher aggression and hostility as well as increased suicidality in persons with alcoholism.

This study has some limitations. As in most complex brain imaging studies, the sample is relatively small. The study was single blind: subjects always received placebo first. We also did not use a healthy comparison group. The results of our study should be treated with caution until replicated.

In summary, higher aggression and hostility in MDD patients with alcoholism may be related to greater hypofrontality in this patient group. The fact that the observed group difference disappeared after the fenfluramine challenge suggests that serotonergic mechanisms play a role in the observed differences between the groups. It also suggests that serotonergic antidepressants may be useful in the treatment of MDD patients with comorbid alcoholism.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Juan J. Carballo holds an Alicia Koplowitz Fellowship in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The authors thank Dianne M. Currier, Ph.D. and Nita Makhija, Ed.M. for their help in preparing the manuscript.

Role of the funding source

Funding for this study was partially provided by NIMH Grant MH40695; the NIMH had no further role in this study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Leo Sher designed the study, managed literature searches, and worked on all versions of the manuscript. Mathew S. Milak managed analyses of neuroimaging data and contributed to the study design. Leo Sher and Juan J. Carballo undertook the statistical analysis of clinical and physiological data. Ramin V. Parsey, Thomas B. Cooper, Kevin M. Malone, Maria A. Oquendo and J. John Mann contributed to the implementation of the study and the interpretation of the study results. Ramin V. Parsey, Maria A. Oquendo, J. John Mann and Juan J. Carballo worked on the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Agren H, Reibring L. PET studies of presynaptic monoamine metabolism in depressed patients and healthy volunteers. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27:2–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) APA Press; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AD, Oquendo MA, Parsey RV, Milak MS, Campbell C, Mann JJ. Regional brain responses to serotonin in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2004;82(3):411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango V, Underwood MD, Gubbi AV, Mann JJ. Localized alterations in pre- and postsynaptic serotonin binding sites in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex of suicide victims. Brain Res. 1995;688(1-2):121–133. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00523-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle TY, Chaikelson JS, Gold DP. Social drinking and cognitive functioning revisited: the role of intellectual endowment and psychological distress. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55(3):352–361. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RW, Morris JB, Beck AT. Cross-validation of the Suicidal Intent Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1974a;34(2):445–446. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1974.34.2.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974b;42(6):861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M. Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1975;132(3):285–287. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979;47(2):343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Goodwin FK. Human aggression and suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1986;16(2):223–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1986.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Wu J, Siegel BV, Hackett E, Trenary M, Abel L, Reynolds C. Effect of sertraline on regional metabolic rate in patients with affective disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 1997;41(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000;4(6):215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J. Consult. Psychol. 1957;21(4):343–349. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buydens-Branch L, Branchey MH, Noumair D. Age of alcoholism onset. I. Relationship to psychopathology. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1989;46(3):225–230. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810030031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DB, Turner P. Plasma concentrations of fenfluramine and its metabolite, norfenfluramine, after single and repeated oral administration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1971;43:465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, Cohen JD. Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection and the online monitoring of performance. Science. 1998;280(5364):747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Mezzich J, Cornelius MD, Fabrega H, Jr., Ehler JG, Ulrich RF, Thase ME, Mann JJ. Disproportionate suicidality in patients with comorbid major depression and alcoholism. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152(3):358–364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Day NL, Thase ME, Mann JJ. Patterns of suicidality and alcohol use in alcoholics with major depression. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20(8):1451–1455. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Clark DB, Salloum IM, Bukstein OG, Kelly TM. Interventions in suicidal alcoholics. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28(5 Suppl.):89S–96S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000127418.93914.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KM, Blackburn IM. Co-morbid depression and drinking outcome in those with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33(5):482–487. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/33.5.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudet D, Hommer D, Higley JD, Andreason PJ, Moneman R, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. Cerebral glucose metabolism, CSF 5-HIAA levels and aggressive behavior in rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152(12):1782–1787. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC. Functional anatomical abnormalities in limbic and prefrontal cortical structures in major depression. Prog. Brain Res. 2000;126:413–431. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Schuckit MA, Johnson BA, Goldman D. Genetics of alcoholism using intermediate phenotypes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003;27(2):169–176. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000052702.77807.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ. Commentary and opinion: II. Statistical parametric mapping: ontology and current issues. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15(3):361–370. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D’Amico EJ. Neurobiological bases of alcohol’s psychological effects. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 422–455. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM. Network memory. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(10):451–459. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Higley JD, Gorey JG, Saunders RC, Jones DW, Hommer D, Zajicek K, Suomi SJ, Lesch KP, Weinberger DR, Linnoila M. In vivo association between alcohol intoxication, aggression, and serotonin transporter availability in nonhuman primates. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1023–1028. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Jones DW, Bissette G, Hommer D, Ragan P, Knable M, Wellek S, Linnoila M, Weinberger DR. Relationship between cortisol and serotonin metabolites and transporters in alcoholism [correction of alcolholism] Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002;35(4):127–134. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR. The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1988;49(3):219–224. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz LR, Volicer L, D’Angelo N, Gadish D. Additional psychiatric illness by Diagnostic Interview Schedule in male alcoholics. Compr. Psychiatry. 1990;31(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(90)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang LH, Ashby CR, Jr., Kasser RJ, Wang RY. The effect of intraventricular administration of the 5-HT3 receptor agonist 2-methylserotonin on the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo chronocoulometric study. Brain Res. 1990;513(1):156–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91103-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Mendlin A, Jacobs BL. Electrical stimulation of rat medial prefrontal cortex enhances forebrain serotonin output: implications for electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SH, Evans KR, Kruger S, Mayberg HS, Meyer JH, McCann S, Arifuzzman AI, Houle S, Vaccarino FJ. Changes in regional brain glucose metabolism measured with positron emission tomography after paroxetine treatment of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):899–905. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMarquand D, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C. Serotonin and alcohol intake, abuse, and dependence: findings of animal studies. Biol. Psychiatry. 1994;36(6):395–421. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Nielsen SL, Chiles JA. Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the reasons for living inventory. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983;51(2):276–286. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovinger DM, White G. Ethanol potentiation of 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor-mediated ion current in neuroblastoma cells and isolated adult mammalian neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40(2):263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers MF, Maltzman I. Selective effects of alcohol on Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86(4):399–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb03417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Henteleff RA, Lagattuta TF, Perper JA, Li S, Arango V. Lower 3H-paroxetine binding in cerebral cortex of suicide victims is partly due to fewer high affinity, non-transporter sites. J. Neural Transm. 1996a;103(11):1337–1350. doi: 10.1007/BF01271194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Malone KM, Diehl DJ, Perel J, Nichols TE, Mintun MA. Positron emission tomographic imaging of serotonin activation effects on prefrontal cortex in healthy volunteers. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996b;16(3):418–426. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199605000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Oquendo M, Underwood MD, Arango V. The neurobiology of suicide risk: a review for the clinician. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1999;60(2):7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Huang YY, Underwood MD, Kassir SA, Oppenheim S, Kelly TM, Dwork AJ, Arango V. A serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and pre-frontal cortical binding in major depression and suicide. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57(8):729–738. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Brent DA, Arango V. The neurobiology and genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: a focus on the serotonergic system. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24(5):467–477. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Brannan SK, Tekell JL, Silva JA, Mahurin RK, McGinnis S, Jerabek PA. Regional metabolic effects of fluoxetine in major depression: serial changes and relationship to clinical response. Biol. Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):830–843. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath PJ, Nunes EV, Quitkin FM. Current concepts in the treatment of depression in alcohol-dependent patients. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2000;23(4):695–711. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messa C, Colombo C, Moresco RM, Gobbo C, Galli L, Lucignani G, Gilardi MC, Rizzo G, Smeraldi E, Zanardi R, Artigas F, Fazio F. 5-HT(2A) receptor binding is reduced in drug-naive and unchanged in SSRI-responder depressed patients compared to healthy controls: a PET study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167(1):72–78. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milak MS, Parsey RV, Keilp J, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Neuroanatomic correlates of psychopathologic components of major depressive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):397–408. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NS, Klamen D, Hoffmann NG, Flaherty JA. Prevalence of depression and alcohol and other drug dependence in addictions treatment populations. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 1996;28(2):111–124. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1996.10524384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumeister A. Tryptophan depletion, serotonin, and depression: where do we stand? Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2003;37(4):99–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo I, Hamon M. Neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory mechanisms involved in alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Neurochem. Int. 1995;26(4):305–336. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)00139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman ME, Shapira B, Lerer B. Evaluation of central serotonergic function in affective and related disorders by the fenfluramine challenge test: a critical review. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1998;1(1):49–69. doi: 10.1017/S1461145798001072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan K, Rynne C, Miller J, O’Sullivan S, Fitzpatrick V, Hux M, Cooney J, Clare A. A follow-up study on alcoholics with and without co-existing affective disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1988;152:813–819. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ. Risk factors for suicidal behavior: utility and limitations of research instruments. In: First MB, editor. Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Vol. 22. APPI Press; Washington, DC: 2003a. pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Placidi GP, Malone KM, Campbell C, Keilp J, Brodsky B, Kegeles LS, Cooper TB, Parsey RV, van Heertum RL, Mann JJ. Positron emission tomography of regional brain metabolic responses to a serotonergic challenge and lethality of suicide attempts in major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003b;60(1):14–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Krunic A, Parsey RV, Milak M, Malone KM, Anderson A, van Heertum RL, Mann JJ. Positron emission tomography of regional brain metabolic responses to a serotonergic challenge in major depressive disorder with and without borderline personality disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;6:1163–1172. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JB, Rothfleisch J, Zelazo PD, Pihl RO. Acute alcohol intoxication and cognitive functioning. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1990;51(2):114–122. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):515–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratsma JE, Van Der SO, Gunning WB. Neurochemical markers of alcoholism vulnerability in humans. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(6):522–533. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.6.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosel P, Arranz B, Urretavizcaya M, Oros M, San L, Vallejo J, Navarro MA. Different distributions of the 5-HT re-uptake complex and the postsynaptic 5-HT(2A) receptors in Brodmann areas and brain hemispheres. Psychiatry Res. 2002;111(2–3):105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, DeJong J, Lamparski D, Adinoff B, George T, Moore V, Garnett D, Kerich M, Linnoila M. Mental disorders among alcoholics. Relationship to age of onset and cerebrospinal fluid neuropeptides. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1991a;48(5):423–427. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810290035006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, DeJong J, Lamparski D, George T, Linnoila M. Depression among alcoholics. Relationship to clinical and cerebrospinal fluid variables. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1991b;48(5):428–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810290040007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Harris RA. Neurobiology of alcohol abuse. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13(5):206–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90065-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Gulliver SB, Colby SM, Sirota AD, Niaura R, Abrams DB. The effects of cue exposure on reaction time in male alcoholics. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55(5):629–633. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Genetic and clinical implications of alcoholism and affective disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):140–147. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Winokur G. A short term follow up of women alcoholics. Dis. Nerv. Syst. 1972;33(10):672–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. Alcoholism and suicidal behavior: a clinical overview. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;113(1):13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicide. In: Soares JC, Gershon S, editors. Textbook of Medical Psychiatry. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2003. pp. 701–711. [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Oquendo MA, Li S, Huang Y, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Lower CSF homovanillic acid levels in depressed patients with a history of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003a;28(9):1712–1719. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Oquendo MA, Li S, Ellis S, Brodsky BS, Malone KM, Cooper TB, Mann JJ. Prolactin response to fenfluramine administration in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression and healthy controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003b;28(4):560–574. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Zalsman G, Mann JJ. The relationship of aggression to suicidal behavior in depressed patients with a history of alcoholism. Addict. Behav. 2005;30(6):1144–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ, Buchsbaum MS, New AS, Spiegel-Cohen J, Wei T, Hazlett EA, Sevin E, Nunn M, Mitropoulou V. d, l-fenfluramine response in impulsive personality disorder assessed with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20(5):413–423. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spak L, Spak F, Allebeck P. Alcoholism and depression in a Swedish female population: co-morbidity and risk factors. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000;102(1):44–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Mann JJ. Increased serotonin-2 binding sites in frontal cortex of suicide victims. Lancet. 1983;1(8318):214–216. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92590-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Virgilio J, Gershon S. Tritiated imipramine binding sites are decreased in the frontal cortex of suicides. Science. 1982;216(4552):1337–1339. doi: 10.1126/science.7079769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. The prevalence and impact of alcohol problems in major depression: a systematic review. Am. J. Med. 2005;118(4):330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Salloum IM, Cornelius JD. Comorbid alcoholism and depression: treatment issues. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 20):32–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Patrick C. Suicide risk in externalizing syndromes: temperamental and neurobiological underpinnings. In: Joiner TE, Rudd D, editors. Suicide Science: Expanding the boundaries. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 2000. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2000;10(3):318–325. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams W, Reimold M, Kerich M, Hommer D, Bauer M, Heinz A. Glucose utilization in the medial prefrontal cortex correlates with serotonin turnover rate and clinical depression in alcoholics. Psychiatry Res. 2004;132(3):219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1992;16(4):620–633. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]