Abstract

Patients with altered taste perception following stroke are at risk for malnutrition and associated complications that may impede recovery and adversely affect quality of life. Such deficits often induce and exacerbate depressive symptomatology, which can further hamper recovery. It is important for clinicians and rehabilitation specialists to monitor stroke patients for altered taste perception so that this issue can be addressed. The authors present the case of a patient who experienced an isolated ischemic infarct affecting a primary cortical taste area. This case is unusual in that the isolated injury allowed the patient to remain relatively intact cognitively and functionally, and thus able to accurately describe her taste-related deficits. The case is further used to describe the relevant neurological taste pathways and review potential taste-related therapies.

Keywords: dysgeusia, nutrition, rehabilitation, stroke, taste disorder

Patients with altered taste perception following stroke may be at risk for poor nutrition and depression that can impede their recovery and adversely affect their quality of life. Impaired taste perception can result from lesions in several locations including the pons, insular cortices, and specific thalamic nuclei.1–10 Several case reports have detailed altered taste as a result of isolated pontine lesions2–6,10 as well as both isolated right and left insular lesions.11,12 Deficits including ageusia (inability to taste), hypogeusia (decreased ability to taste), and dysgeusia (distorted ability to taste) have also been described.7,9,10

Taste perception was initially thought to be processed without decussation,2 but more recently complete or bilateral decreased perception has been attributed to isolated left insular infarcts,7,11–13 suggesting that this site may receive contralateral projections or function as an important higher order center for taste perception. Isolated insular infarcts affecting taste are uncommon, and thus the symptoms of altered taste may go unrecognized in patients experiencing larger middle cerebral artery (MCA) territorial infarcts, thereby limiting patient recovery and resulting in worse outcomes. Outcomes may be limited because of lack of awareness among clinicians and caretakers and few available resources for treatment.

We present a review of literature describing taste impairments following stroke as it relates to a case of dysgeusia secondary to unilateral ischemic insular infarction in a patient presenting with a complete left MCA syndrome successfully treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV-tPA).

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old woman with a history of sick sinus syndrome status post pacemaker placement was cooking dinner when she developed acute onset right-sided weakness and slid to the floor. She was confused and made repetitive movements but did not speak or follow commands. Her NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 19 on arrival in the emergency room. The clinical presentation was consistent with a complete left MCA distribution infarct. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed no intracranial hemorrhage, and the patient received weight-based IV-tPA therapy approximately 2.5 hours after symptom onset.

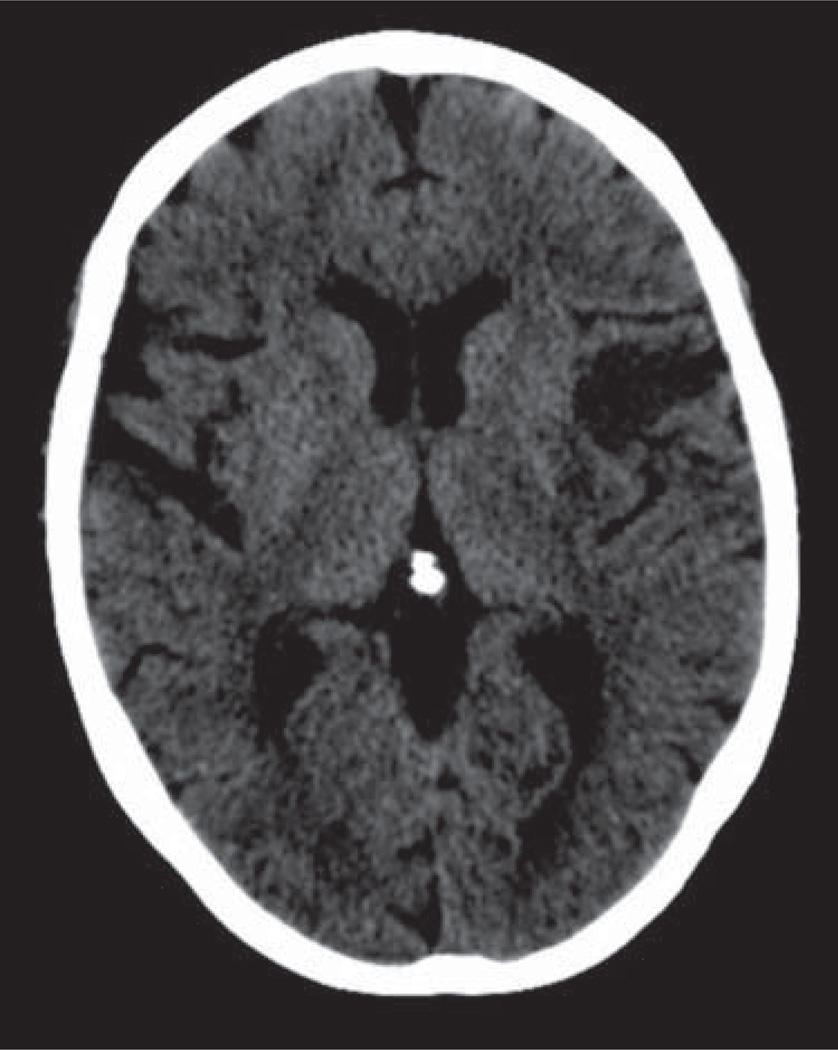

The patient’s exam improved after completion of the IV-tPA infusion to an NIHSS score of 10 with continued deficits of orientation, horizontal gaze palsy, right facial weakness, drift of the right arm and leg, aphasia, and dysarthria. A repeat CT head showed a hypodense lesion consistent with evolution of infarct within the insular cortex on the left (Figure 1), with CT angiography of the head and neck demonstrating no vascular occlusions or flow-limiting stenosis.

Figure 1.

CT head without contrast performed at approximately 30 hours after symptom onset shows hypodense region within the left anterior insular cortex. The remaining middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory shows normal gray-white differentiation.

During the hospitalization, the patient experienced continued improvement of her speech and was able to converse with staff and follow simple and some complex commands. She was noted to have occasional paraphasic errors and some difficulty with writing. The patient had only minor right-sided weakness and was able to sense vibration, proprioception, temperature, and pin equally in all 4 extremities. She was discharged to home with outpatient occupational and speech therapy.

Over the next several months, the patient continued to have difficulty with multistep tasks such as cooking. She was able to read only simple books. She had great difficulty in composing letters or e-mail and continued to have paraphasic errors, misspellings, and incorrect tense usage. Additionally, she reported that music was no longer enjoyable and described her prior favorite composers’ work as “loud noise.”

On follow-up visit at 6 months, the patient had lost ~14 lbs (6.35 kg) and complained of “distaste” for her preferred foods. The patient reported that she thought food tasted “like nothing” at the time she was hospitalized but did not think this was necessarily abnormal. Upon return to her home and her usual diet, she discovered that “everything tastes like dirt.” Her former favorite foods, including chicken, potatoes, ham, vegetables, wine, and coffee, were unappealing. The patient noted that not all of the foods taste alike, but they were perceived as unusual flavors that did not resemble food. This was most severe over the first several weeks to months following the stroke, resulting in her eating less and losing weight. She also felt isolated from family and friends because she did not enjoy sharing meals or going to restaurants for social occasions.

At 6 months, the patient’s speech and writing continued to improve as she participated in speech therapy and consistently spent time each day composing letters to family and reading. She graduated from children’s books to simple novels, but still had difficulty following intricate plots. The patient’s aversion to music was similarly rehabilitated by initially listening to solo instruments and graduating to more intricate compositions. She continued to lament her inability to hum or sing, but she was pleased to have regained pleasure from some elements of music.

The patient continued to sample different foods and by 9 months post stroke had identified several foods that she could taste and enjoy. She found that tomato sauce with pasta or beef dishes were the most palatable, and she replaced coffee with tea. She noted that sweet foods and sugar tasted as expected, and she was able to enjoy chocolate. One year following the stroke, she continued to perceive the taste of chicken and potatoes as “sawdust.”

Discussion

Defining taste

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are the 2 primary “chemical” senses. The 4 well-known taste receptors detect sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. The sweet and bitter receptors are relatively well established, but the sour receptor has only recently been identified and the salt receptor is not yet known.14 A fifth receptor, for a sensation called umami, was recently identified in 2000.15 The umami receptor detects the amino acid glutamate, a flavoring commonly found in meat and in artificial flavorings such as monosodium glutamate. Unlike taste, there are hundreds of olfactory receptors, each binding to a particular molecular feature. Odor molecules possess a variety of features and act to excite specific receptors more or less strongly. The combination of excitatory signals from different receptors makes up what is perceived as the molecule’s smell. It is important to be aware that taste is not the same as flavor. Flavor includes the smell of a food as well as its taste.

Anatomy of taste

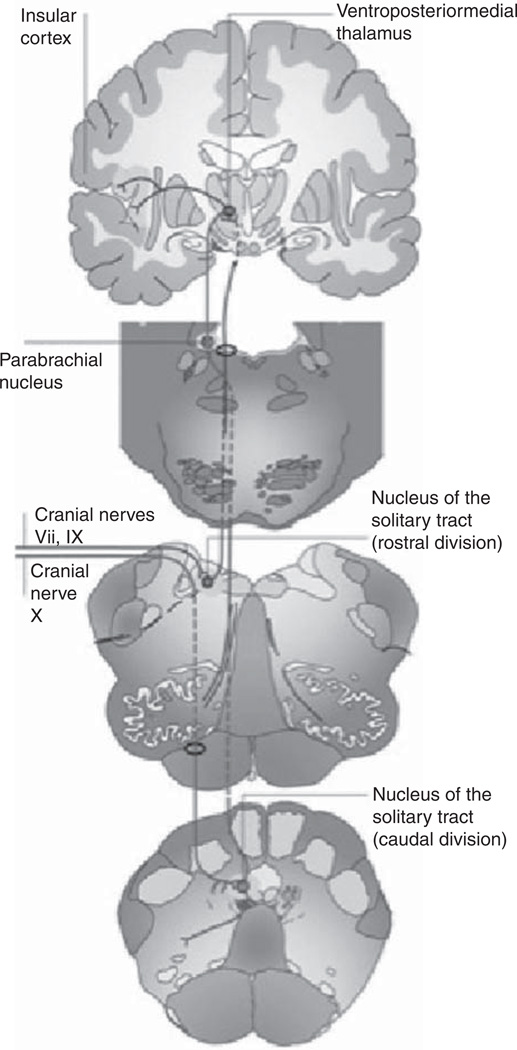

The anatomic gustatory pathway involves afferents from the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves with projections to the solitary tract nucleus (STN). Relay neurons from the STN form a gustatory lemniscus that ascends ipsilaterally through the pons2,2,5,16 (Figure 2). The gustatory pathway is less precisely defined thereafter. Landis et al suggest that the tract may decussate as it approaches the thalamic nuclei, including the ventroposteromedial nucleus (VPM) and dorsomedial nuclei (DM), based on hemigustatory symptoms reported in strokes of the midbrain, thalamus, or insular cortices.5 Pritchard and colleagues assert that the processing from pons to the parvicellular division of the thalamic VPM nucleus is ipsilateral, as is the following tract to gustatory cortex within the rostrodorsal insula.7 DM thalamic function appears to be related to the interpretation of tastes as pleasurable, as supported by the case of a patient who experienced loss of food and odor appeal despite intact perception of flavors and aromas following bilateral DM thalamic infarcts.8 As related to this section and those that follow, refer to Table 1, which summarizes several important studies and literature reports describing taste-related deficits occurring secondary to stroke and/or brain injury.

Figure 2.

Diagram of central taste pathway. Inputs from cranial nerves VII, IX, and X synapse in the medulla in the solitary nucleus. Ascending fibers travel ipsilaterally through the pons to their targets within the thalamus, the ventroposteriormedial (VPM), and dorsomedial (DM) nuclei. The projections from the thalamus are to the insular and orbitofrontal cortex, though the precise routes taken by these tracts are debated in the literature. Reprinted, with permission, from Bermudez-Rattoni F. Molecular mechanisms of taste-recognition memory. Nature Neurosci Rev. 2004;5:209-217. Copyright © Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Table 1.

Selected reports of taste deficits following stroke or brain injury

| Patients | Study type | Lesion location | Findings | Significance | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Anatomical pathologic study | Unilateral pontine tegmentum hemorrhage | Ipsilateral atrophy of neurons in nucleus solitarius, decreased fiber density in solitary tract | Suggests gustatory lemniscus travels ipsilaterally through pons after leaving STN | Goto et al, 19832 |

| 3 | Clinical | Unilateral pontine tegmentum hemorrhage | Hemiageusia | Suggests gustatory lemniscus travels ipsilaterally through pons after leaving STN | |

| 1 | Clinical | Unilateral pontine hemorrhage | Hemiageusia | Suggests gustatory lemniscus travels ipsilaterally through pons after leaving STN | Nakajima et al, 19833 |

| 1 | Clinical | Unilateral pontine hemorrhage | Hemiageusia-contralateral | Suggests decussation of fibers at level of pons | Sunada et al, 19954 |

| 1 | Clinical | Ischemic infarct of right pons, medial cerebellar peduncle, and right cerebellum | Hemiageusia | Suggests gustatory lemniscus travels ipsilaterally through pons after leaving STN May decussate at or above midbrain as it approaches DM and VPM nuclei of thalamus | Landis et al, 20065 |

| 3 | Clinical | Pontine, thalamic, internal capsule infarcts | Hemiageusia ipsilateral to pontine lesion, contralateral to thalamic and internal capsule lesions | Suggests gustatory lemniscus ascends ipsilaterally through pons, crosses at or above midbrain | Onoda et al, 19996 |

| 4 | Clinical | Stroke or tumor invasion of dorsal insula | Hypogeusia or dysgeusia ipsilateral to lesion; however, left insular deficits associated with objective decrease in taste perception bilaterally | Supports ipsilateral tract from pons to VPM nucleus and continued ipsilateral communication with gustatory cortex in rostrodorsal insula | Pritchard et al, 19997 |

| 1 | Clinical | Bilateral DM thalamic infarcts | Appeal of food and odors lost; retained ability to perceive flavor and aromas | Left insula may receive bilateral taste input DM nucleus of thalamus plays role in interpretation of tastes as pleasurable | Rousseaux et al, 19966 |

| 1 | Clinical | Left insular infarction | Dysgeusia | Role of insular cortex in taste interpretation | Metin et al,200713 |

| 1 | Clinical | Left posterior insular infarct | Bilateral deficit in taste of salt and sour | Supports role of rostrodorsal insular cortex in taste processing | Cereda et al.200211 |

| 1 | Clinical | Left insular infarction | Contralateral hypersensitivity to taste | Suggests possibility of hyperintensity due to loss of cortical inhibition of left insula | Mak et al, 200512 |

| 4 | Clinical | Cortical infarcts with fronto-opercular involvement | Dysgeusia and changes in food preference | Role of fronto-opercular cortex in taste processing | Kim and Choi, 200221 |

| 1 | Clinical | Infarct in right posterior insula and frontoparietal cortex; chronic infarction in same areas on left | Dysgeusia only after bilateral MCA infarcts | Perception and processing of flavor may involve integration of information from several cortical regions; significant symptoms may become apparent with bilateral involvement | Moo and Wityk, 199918 |

| 24 | Clinical Patients reporting dysesthesia following stroke underwent evaluation for taste disorder by filter paper testing and electrogustometry | Infarct or hemorrhage in pons, cerebellum, thalamus, putamen, internal capsule, or insula | 9 of 11 reporting subjective dysgeusia showed impaired taste recognition 11 of 13 with dysesthesia only showed significant objective deficits in taste recognition | Stroke-induced taste disorder can result from damage to somatosensory pathways, independent of gustatory pathways Taste disorders are common in stroke and may not be noticed by patients | Etoh et al,2008l0 |

| 102 | Clinical Prospective, 1-year study to determine incidence of taste disorders following stroke | Hemispheric, subcortical, thalamic, brainstem | 31 demonstrated objective gustatory deficits, 7 demonstrated lateralized impairment | 30% of patients experienced dysgeusia or ageusia Predictors of taste disorder included male gender, higher NIHSS score, dysphagia, partial anterior circulation stroke, particularly frontal lobe involvement | Heckman et al, 20059 |

Note: STN = solitary tract nucleus; DM = dorsomedial nuclei; VPM = ventroposteromedial nucleus; NIHSS = NIH Stroke Study.

Cortical processing

The orbitofrontal cortex5,9 is believed to play a central role in taste processing given that it receives projections from the thalamic relays and is widely accepted as a primary site receiving olfactory projections.17 The insular cortex has also been suggested as a primary gustatory cortex,7,11,13 with its importance in the processing of gustatory information supported by several case series7,11–13,18 and a prospective observational study.9 Recent work by Chen et al supports the existence of a gustotopic map in the mammalian insular cortex, in which each taste modality is encoded by a specific group of neurons.19 Further investigation is needed to determine whether this same organization is present in the human brain.

Interpretation of taste: theories and mechanisms

Perception of taste, identification of flavor, and interpretation as hedonic or unpleasant are all functions of the gustatory pathway as a whole. Landis et al propose that central lesions cause disorders of perception (hemiageusia or hypoageusia), whereas peripheral nerve lesions result in altered taste interpretation with maintenance of taste perception.5 However, the cases described by Rousseaux8 with dorsomedial thalamic insult, Metin13 with insular infarct, and our current patient suggest that this distinction may not be so precise. Pritchard et al suggest that the gustatory pathway is one that builds on information processed at each level beginning with the receptors themselves and terminating in multiple cortical locations. Thus, although the cortical projections are not needed for taste perception, more sophisticated interpretations of flavor and the hedonic qualities of the flavor are perceived at cortical levels.7 This theory is supported by numerous functional MRI studies demonstrating that the insular, parietal, frontal opercular, and orbitofrontal cortical areas are activated with gustatory pathway stimulation.17,20 It is important to note that damage to the somatosensory pathways may also result in dysgeusia independent of central gustatory pathways, based on findings by Etoh et al,10 who studied objective dysgeusia (as measured with electrogustometry and filter paper testing) in patients with lesions in the pons, thalamus, putamen, or insula.

Our patient did not undergo formal taste and smell testing secondary to her progressive improvements, although in retrospect this may have been beneficial because both chemical senses are often confounded.2 Such testing may have provided psychophysical evidence (eg taste15 and smell5,7) that our patient had a definitive taste problem and not an olfactory problem. However, given that the patient reported certain food items tasted like “sawdust,” we believe that she was indeed experiencing a primary taste problem rather than a parosmia. Testing should be considered if the patient is not meeting goals of rehabilitation, because altered taste perception may lead to depression, weight loss, and malnutrition, all of which may act to confound rehabilitation efforts.

Consequences of altered taste

Many studies have demonstrated that medically acquired taste and smell disturbances can adversely affect quality of life. Affected patients may report changes in food preferences21 and find certain foods less palatable, leading to unintentional weight loss22–24 and decreased energy level. Many patients report avoiding social activities because of loss of enjoyment in dining out and other food-related group activities. Impaired taste can also indirectly result in undesirable health effects secondary to changes in dietary habits. In one case study, a patient with dysgeusia following minor stroke developed uncontrolled hypertension due to a dramatic increase in salt intake in an attempt to improve food flavor.25

Weight loss and malnutrition

Stroke patients experiencing taste loss or disturbance may have unintentional weight loss or difficulty maintaining a healthy weight.8,26,27 In a cohort of stroke survivors,28 24% experienced weight loss of greater than ~6.6 lbs (3 kg). Those identified as having eating difficulties were more likely to experience significant weight loss at 4-month follow-up.28 Weight loss often coincides with malnutrition in the setting of critical illness, leading to increased risk of poststroke complications,29 including gastrointestinal bleeding, pneumonia, and other infections.29,30 Acute stroke patients who are malnourished are at risk for poorer outcomes,28 independent of baseline nutritional status and age,29–31 and are also at risk for continued undernourishment during hospitalization.32 Patients with eating difficulties on admission have been shown to require longer hospital admissions and are more likely to require institutionalized care following discharge.33

Depression

Impaired olfaction occurs more frequently in patients with major depression34 and is associated with higher scores on depression inventories.35,36 Because olfaction and gustation are linked, it is plausible that patients with ageusia or dysgeusia following stroke may be at risk for depression. One pilot study of stroke patients at 6 months following hospital discharge showed a significant relationship between self-reported fatigue and impaired nutritional status, with women and older patients being most affected.37 Another study demonstrated that stroke patients with poorer nutrition are more likely to suffer from depression and report lower quality of life.27 Intervening on this cycle early in stroke recovery becomes paramount to optimize outcomes.

Identifying and addressing taste disorders

Taste disorders of patients following stroke are underdiagnosed owing to a lack of awareness and the failure to routinely test taste perception in this population. Patients not undergoing poststroke rehabilitation, and those lost to follow-up, may be particularly at risk. We therefore propose that all stroke patients, especially those identified as having eating difficulties, be screened for taste and olfactory disorders early in their course. Screening may involve asking questions regarding changes in taste and eating practices, objective qualitative assessments of smell and taste, or formal testing with taste strips38 or electrogustometry.39 Individualized attention to patient nutrition and activity has been shown to reduce risk of weight loss and improve certain functional outcomes as well as overall quality of life in acute stroke patients at risk for malnutrition.40 Dietary education, including the addition of flavor enhancers to food, may also be helpful.41 Education of care providers and implementation of practices designed to identify eating difficulties and provide supplementary nutrition may decrease incidence of malnutrition.42 Although there is currently no standard pharmacologic treatment for taste disorders, there is potential for use of existing medications or development of new substances that will enhance food palatability. One small study found that carbamazepine improved stroke-induced dysgeusia.10 Activation of cannabinoid receptors by delta-9-tetrahydrocannibinol has been shown to improve food palatability, thus increasing appetite and food intake, possibly through stimulation of dopamine production in the nucleus accumbens.43–46 Future research in this area will be helpful in identifying potential therapies.

Conclusion

The pathways for processing smell and taste disorders are continuing to be elucidated through characterization of deficits in cases such as the patient described herein. Recognition of potential deficits in areas essential for the processing of smell, taste, and flavor perception will allow clinicians to optimally screen, evaluate, and counsel patients to improve their quality of life following stroke. Future research to identify taste-enhancing therapies will help improve health and quality of life in patients affected by stroke-induced taste disorders.

Acknowledgments

Dr. John W. Cole was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Baltimore, Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service; the Department of Veterans Affairs Stroke Research Enhancement Award Program; the University of Maryland General Clinical Research Center (grant M01 RR 165001), General Clinical Research Centers Program, National Center for Research Resources; and the National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01 NS069208-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ropper AH, Samuels MA. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto N, Yamamoto T, Kaneko M, Tomita H. Primary pontine hemorrhage and gustatory disturbance: clinicoanatomic study. Stroke. 1983;14(4):507–511. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakajima Y, Utsumi H, Takahashi H. Ipsilateral disturbance of taste due to pontine haemorrhage. J Neurol. 1983;229(2):133–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00313454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunada I, Akano Y, Yamamoto S, Tashiro T. Pontine haemorrhage causing disturbance of taste. Neuroradiology. 1995;37(8):659. doi: 10.1007/BF00593388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landis BN, Leuchter I, San Millan Ruiz D, Lacroix JS, Landis T. Transient hemiageusia in cerebrovascular lateral pontine lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(5):680–683. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.086801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onoda K, Ikeda M. Gustatory disturbance due to cerebrovascular disorder. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(1):123–128. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pritchard TC, Macaluso DA, Eslinger PJ. Taste perception in patients with insular cortex lesions. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113(4):663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rousseaux M, Muller P, Gahide I, Mottin Y, Romon M. Disorders of smell, taste, and food intake in a patient with a dorsomedial thalamic infarct. Stroke. 1996;27(12):2328–2330. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.12.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heckmann JG, Stossel C, Lang CJ, Neundorfer B, Tomandl B, Hummel T. Taste disorders in acute stroke: a prospective observational study on taste disorders in 102 stroke patients. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1690–1694. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000173174.79773.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etoh S, Kawahira K, Ogata A, Shimodozono M, Tanaka N. Relationship between dysgeusia and dysesthesia in stroke patients. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118(1):137–147. doi: 10.1080/00207450601044686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cereda C, Ghika J, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J. Strokes restricted to the insular cortex. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1950–1955. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038905.75660.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mak YE, Simmons K, Gitelman D, Small D. Taste and olfactory intensity perception changes following left insular stroke. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119(6):1693–1700. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.6.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metin B, Melda B, Birsen I. Unusual clinical manifestation of a cerebral infarction restricted to the insulate cortex. Neurocase. 2007;13(2):94–96. doi: 10.1080/13554790701316100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarmolinsky DA, Zuker CS, Ryba NJP. Common sense about taste: from mammals to insects. Cell. 2009;139(2):234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindemann B. A taste for umami. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(2):99–100. doi: 10.1038/72153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uesaka Y, Nose H, Ida M, Takagi A. The pathway of gustatory fibers of the human ascends ipsilaterally in the pons. Neurology. 1998;50(3):827–828. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolls ET, Critchley HD, Mason R, Wakeman EA. Orbitofrontal cortex neurons: role in olfactory and visual association learning. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75(5):1970–1981. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moo L, Wityk RJ. Olfactory and taste dysfunction after bilateral middle cerebral artery stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;8(5):353–354. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3057(99)80011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Gabitto M, Peng Y, Ryba NJP, Zuker C. A gustotopic map of taste qualities in the mammalian brain. Science. 2011;333(6047):1262–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1204076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Small DM, Zald DH, Jones-Gotman M, et al. Human cortical gustatory areas: a review of functional neuroimaging data. Neuroreport. 1999;10(1):7–14. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199901180-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JS, Choi S. Altered food preference after cortical infarction: Korean style. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(3):187–191. doi: 10.1159/000047774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Lara K, Sosa-Sanchez R, Green-Renner D, et al. Influence of taste disorders on dietary behaviors in cancer patients under chemotherapy. Nutr J. 2010;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutton JL, Baracos VE, Wismer WV. Chemosensory dysfunction is a primary factor in the evolution of declining nutritional status and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finsterer J, Stllberger C, Kopsa W. Weight reduction due to stroke-induced dysgeusia. Eur Neurol. 2004;51(1):47–49. doi: 10.1159/000075089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czupryniak L, Loba J. Loss of taste-induced hypertension: caveat for taste modulation as a therapeutic option in obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2007;12(1):e11–e13. doi: 10.1007/BF03327775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woschnagg H, Stollberger C, Finsterer J. Loss of taste is loss of weight. Lancet. 2002;359(9309):891. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry L, McLaren S. An exploration of nutrition and eating disabilities in relation to quality of life at 6 months post-stroke. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(4):288–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonsson AC, Lindgren I, Norrving B, Lindgren A. Weight loss after stroke: a population-based study from the Lund Stroke Register. Stroke. 2008;39(3):918–923. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.497602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FOOD Trial Collaboration. Poor nutritional status on admission predicts poor outcomes after stroke: observational data from the FOOD Trial. Stroke. 2003;34(6):1450–1456. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000074037.49197.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davalos A, Ricart W, Gonzalez-Huix F, et al. Effect of malnutrition after acute stroke on clinical outcome. Stroke. 1996;27(6):1028–1032. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandian JD, Jyotsna R, Singh R, et al. Premorbid nutrition and short term outcome of stroke: a multicentre study from India. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(10):1087–1092. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.233429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo SH, Kim JS, Kwon SU, Yun SC, Koh JY, Kang DW. Undernutrition as a predictor of poor clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(1):39–43. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westergren A, Ohlsson O, Hallberg IR. Eating difficulties in relation to gender, length of stay, and discharge to institutional care, among patients in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(10):523–533. doi: 10.1080/09638280110113430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pause BM, Miranda A, Goder R, Aldenhoff JB, Ferstl R. Reduced olfactory performance in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35(5):271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, et al. Smell and taste disorders: a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117(5):519–528. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870170065015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopinath B, Anstey KJ, Sue CM, Kifley A, Mitchell P. Olfactory impairment in older adults is associated with depressive symptoms and poorer quality of life scores. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(9):830–834. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318211c205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westergren A. Nutrition and its relation to mealtime preparation, eating, fatigue and mood among stroke survivors after discharge from hospital: a pilot study. Open Nurs J. 2008;2:15–20. doi: 10.2174/1874434600802010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller C, Kallert S, Renner B, et al. Quantitative assessment of gustatory function in a clinical context using impregnated “taste strips.”. Rhinology. 2003;41(1):2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berling K, Knutsson J, Rosenblad A, von Unge M. Evaluation of electrogustometry and the filter paper disc method for taste assessment. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockholm) 2011;131(5):488–493. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.535850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ha L, Hauge T, Spenning AB, Iversen PO. Individual, nutritional support prevents undernutrition, increases muscle strength and improves QoL among elderly at nutritional risk hospitalized for acute stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(5):567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiffman SS, Sattely-Miller EA, Taylor EL, et al. Combination of flavor enhancement and chemosensory education improves nutritional status in older cancer patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2007;11(5):439–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westergren A, Axelsson C, Lilja Andersson P, et al. Study circles improve the precision in nutritional care in special accommodations. Food Nutr Res. 2009:53. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v53i0.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Luca MA, Solinas M, Bimpisidis Z, Goldberg SR, Di Chiara G. Cannabinoid facilitation of behavioral and biochemical hedonic taste responses. Neuropharmacology. 2011;63(1):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abel EL. Cannabis: effects on hunger and thirst. Behav Biol. 1975;15(3):255–281. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)91684-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foltin RW, Fischman MW, Byrne MF. Effects of smoked marijuana on food intake and body weight of humans living in a residential laboratory. Appetite. 1988;11(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(88)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeomans MR, Gray RW. Opioid peptides and the control of human ingestive behaviour. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26(6):713–728. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]