Abstract

Few data are available on physician perceptions of osteoporosis medication adherence. This study compared physician-estimated medication adherence with adherence calculated from their patients' pharmacy claims. Women aged ≥45 years, with an osteoporosis-related pharmacy claim between January 1, 2005 and August 31, 2008, and continuous coverage for ≥12 months before and after first (index) claim, were identified from a commercial health plan population. Prescribing physicians treating ≥5 of these patients were invited to complete a survey on their perception of medication adherence and factors affecting adherence in their patients. Pharmacy claims-based medication possession ratio (MPR) was calculated for the 12-month post-index period for each patient. Physicians who overestimated the percentage of adherent (MPR ≥0.8) patients by ≥10 points were considered “optimistic”. Logistic regression assessed physician characteristics associated with optimistic perception of adherence. A total of 376 (17.2%) physicians responded to the survey; 62.0% were male, 58.2% were aged 45 to 60 years, 55.3% had ≥20 years of practice, and 35.4% practiced in an academic setting. Participating physicians prescribed osteoporosis medications for 2748 patients with claims data (mean [SD] age of 62.0 [10.6] years). On average, physicians estimated 67.2% of their patients to be adherent; however, only 40% of patients were actually adherent based on pharmacy data. Optimistic physicians (73.4%) estimated 71.9% of patients to be adherent while only 32.2% of their patients were adherent based on claims data. Physicians in academic settings were more likely to be optimistic than community-based physicians (odds ratio 1.69, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.85). Overestimation of medication adherence may impede physicians' ability to provide high quality care for their osteoporosis patients.

Keywords: Postmenopausal osteoporosis, Adherence, Compliance, Persistence, Bisphosphonates

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a degenerative bone disease that is common in postmenopausal women [1]. In the United States (U.S.), 10 million men and women have osteoporosis and the number of affected individuals is expected to increase to 14 million by 2020 [1]. Fracture is the most costly consequence of osteoporosis and fracture-related costs are projected to increase from $17 billion in 2005 to over $22 billion by 2020 [2]. In Europe, osteoporotic fractures accounted for an estimated 1.75% of the total disease burden, and for more disability-adjusted life years lost than most common cancers with the exception of lung cancer [3].

Initial fractures increase the risk of subsequent fractures,with 40% to 60% of individuals with low-trauma fractures experiencing an additional fracture over 10 years, and a 34% higher risk of subsequent fracture among individuals with a previous high-trauma fracture compared with individuals without a fracture history [4,5]. Fractures can also increase subsequent mortality risk for up to 10 years post fracture [6].

Bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid) are commonly prescribed treatments for osteoporosis. Other osteoporosis agents prescribed in the U.S. include raloxifene (a selective estrogen receptor modulator [SERM]), teriparatide (a recombinant form of parathyroid hormone), calcitonin, and denosumab (a RANKL inhibitor) [7]. Estrogen replacement therapy is also prescribed for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, but its use has diminished with increasing long-term safety concerns, and product labeling suggests that if estrogen replacement therapy is prescribed for the prevention of osteoporosis, it should be considered only for women at significant risk of developing postmenopausal osteoporosis [8–10].

Osteoporosis treatment adherence correlates with improvement in bonemineral density and reduction of fracture risk [11]. However, nonadherence is common among osteoporosis patients and mitigates these clinical benefits [12–14]. Physicians who are unaware of what proportion of their own patients is nonadherent may overestimate the therapeutic benefits their patients are receiving, and may be less likely to inquire about their patients' adherence or to provide opportunities to discuss difficulties a patient may have in taking their medications. Although physician perceptions of patients' medication adherence have been examined in therapeutic areas as diverse as diabetes, hypertension, and HIV, little is known about physician perceptions of adherence in osteoporosis patients [15–19].

Our study was undertaken to 1) compare physician estimates of osteoporosis medication adherence in postmenopausal women with adherence measured using linked pharmacy claims data, and 2) assess physician characteristics associated with misclassification in the estimation of their patients' adherence.

Methods

Data source

All claims data were obtained from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRDSM) which includes information for 43 million individuals enrolled in a variety of Blue Cross/Blue Shield health plans in 14 states. Although the database covers the U.S., the largest proportion of enrollees resided in the Western region. An independent institutional review board approved the study protocol and questionnaire. Physicians provided formal consent to participate, and all survey data were de-identified and reported only in aggregate.

Identification of patients and physicians

Women aged ≥45 years with outpatient pharmacy claim(s) for an oral bisphosphonate (weekly or monthly), calcitonin, SERM, or teriparatide between January 1, 2005 and August 31, 2008 were identified using administrative claims data from the HIRDSM. Physicians were identified by linking eligible women to their prescribing physicians. If contact information for the prescribing physician was unavailable, the patient was excluded from the cohort.

The index date was set to the date of the first osteoporosis pharmacy claim for the eligible osteoporosis medications. Patients were required to have continuous health plan coverage for ≥12 months before and after the index date, and to be new to pharmacologic therapy (i.e., no osteoporosis medication claims in the 12-months pre-index). Patients who had claims for≥2 osteoporosismedications at index,who were diagnosed with malignant neoplasmor Paget's disease, or were receiving medication consistent with the treatment of Paget's disease in the 12-months pre-index, or who had claims for skilled-nursing facility care on the index date were excluded from this study.

Physician survey

Physicians who prescribed index osteoporosis medication for ≥5 study cohort patients between March 15, 2010 and June 22, 2010 were invited via mail, email, or fax to participate in the survey. This ensured that the sample included a range of prescribing physicians, rather than exclusively those who were high volume prescribers of osteoporosis medications. The 26-item physician questionnaire was used to collect information on their demographics (gender, age, geographic region, specialty, years in practice, practice setting, and patient volume), their perceptions of treatment adherence in the postmenopausal osteoporosis patients they treated, approaches to managing osteoporosis, and their perceptions of factors that influenced patient adherence (Table 1). The survey was available in hardcopy and online; the online version was pilot-tested by 10 physicians prior to full implementation. Participating physicians were allowed to terminate the survey at any point and received $100 upon completion. A 20% response rate was targeted.

Table 1.

Physician survey content

| Physician characteristics | Gender, age, years in practice, geographic region, specialty, practice setting, academic affiliation, and patient volume |

| Diagnosing and managing postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) | Equipment used and patient characteristics considered to diagnose osteoporosis Initiating therapy with samples and/or prescriptions |

| Follow-up intervals after prescribing osteoporosis agent(s) | |

| PMO medication adherence | Level of adherence needed for clinical benefit |

| Factors that influence patient adherence Physician behaviors used to support patient adherence (ask patients about problems with their medication; ask family/caregiver about medication adherence; review medical records or pharmacy data for indications of refills) | |

| What percentage of your patients do you estimate adhere to post-menopausal osteoporosis (PMO) medication therapy after 1 year? Adherence is defined as both persistence and compliance (following dosing instructions at least 80% of the time). |

Study measures

The measures for the primary analysis of this study were patients' osteoporosis medication adherence and physician perceptions of patients' osteoporosis medication adherence. Patients' medication adherence was assessed by calculating the medication possession ratio (MPR) for each patient using pharmacy data. MPR was defined as the total number of days of osteoporosis medication supplied in the 12-month post-index period divided by 365 days. Patients with MPR ≥0.8 were considered adherent.

Physician perceptions of patients' medication adherence were assessed from the following survey question: “What percentage of your patients do you estimate adhere to post-menopausal osteoporosis (PMO) medication therapy after 1 year? Adherence is defined as both persistence and compliance (following dosing instructions at least 80% of the time).” Although common definitions of adherence used for research purposes usually distinguish between persistence (i.e. non-discontinuation) and compliance, the question combined these concepts in recognition that a clinician is usually most interested in whether the patient is taking the drug as prescribed, which requires both persistence and compliance. Moreover, self-reported data about drug use provided by patients to their treating physicians during office visits has uncertain validity to help doctors accurately identify and discriminate between nonpersistence and noncompliance, which often overlap. Response categories for this question were recorded in deciles. Separate responses were obtained for weekly oral bisphosphonates, monthly oral bisphosphonates, SERMs, calcitonin, and teriparatide. Physician perceptions of adherence were compared with the pharmacy claims-based MPR, which was considered the gold standard metric.

The analysis determined the differences between the physician's estimate of the percentage of his/her patients that were adherent and the percentage of that physician's patients in the study cohort who achieved pharmacy claims-based MPR ≥0.8. Physicians who overestimated the percentage adherent by at least 10 points were classified as optimistic; all other physicians were considered non-optimistic. In other words, optimistic physicians misclassified at least 10% of their patients as adherent whose MPRs were actually <0.8. To illustrate, if a physician estimated that 90% of his/her patients were adherent, but only 75% had pharmacy claims-based MPR ≥0.8, the difference was 15 points and the physician was considered to be optimistic.

Several other survey questions were designed to measure physician recommendations regarding follow-up visit intervals and perceptions of factors influencing osteoporosis medication adherence, including physician behaviors that could be supportive of improved patient adherence. For comparative purposes, claims data were also used to assess the interval between patient visits with the prescribing physician by assessing the number of days between the visits closest to (before and after) the patient's index date.

Statistical analysis

Geographic region and patient volume were assessed for all invited physicians and participating physicians using available health plan data. Only data from completed surveys were included in the analyses reported here. Frequency distributions and other descriptive statistics were generated for the responses to each survey question. The statistical significance of differences between optimistic and non-optimistic physicians was assessed using Chi-square test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to assess physician characteristics associated with optimistic estimates of adherence while controlling for covariates that were significant in descriptive analyses. Physician characteristics and perceptions of factors that influence patient medication adherence that differed significantly between optimistic and non-optimistic physicians in descriptive analyses were included in the multivariate model. All analyses were completed using SAS® v9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC).

Results

The patient cohort included 2748women (mean [SD] age 62.0 [10.6] years) who had initiated osteoporosis therapy. The largest group of patients resided in the West (41.7%) and the smallest group in the Northeast (11.4%). The remainder of the cohort was split equally between the Midwest and the South. The index medication for the majority of patients in the study cohort was a bisphosphonate (2419, 88.0%).

Of the 2184 physicians who were invited to participate, 376 (17.2%) completed the survey. Table 2 shows that the majority were male (62.0%); between the ages 45 and 60 years (58.2%); and had been in practice for ≥20 years (55.3%). Over one-third (35.9%) were in solo practice and a similar proportion (35.4%) reported academic affiliation. The majority of survey participants were OB/GYN, internal medicine, or family/general practice physicians (33.8%, 30.9%, 23.7%, respectively); 56.9% had 6 to 10 patients in the study cohort, 31.6% had 5 patients, and 11.4% had more than 10 patients (data not shown). The distribution of region and patient volume were generally similar for participating physicians and all invited physicians (data not shown).

Table 2.

Demographics of participating physicians

| All physicians N = 376 |

Optimistic physiciansa N = 277 |

Non-optimistic physiciansa N = 99 |

p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender – n (%) | 0.69 | |||

| Male | 233 (62.0) | 173 (62.5) | 60 (60.6) | |

| Female | 141 (37.5) | 102 (36.8) | 39 (39.4) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0 | |

| Age group, years – n (%) | 0.67 | |||

| 30 to 44 | 76 (20.2) | 56 (20.2) | 20 (20.2) | |

| 45 to 60 | 219 (58.2) | 157 (56.7) | 62 (62.6) | |

| >60 | 76 (20.2) | 60 (21.7) | 16 (16.2) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Years in practice – n (%) | 0.90 | |||

| <5 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 to <10 | 29 (7.7) | 20 (7.2) | 9 (9.1) | |

| 10 to <15 | 59 (15.7) | 45 (16.2) | 14 (14.1) | |

| 15 to <20 | 78 (20.7) | 56 (20.2) | 22 (22.2) | |

| ≥20 | 208 (55.3) | 154 (55.6) | 54 (54.6) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Practice environment | ||||

| Practice setting – n (%) | 0.22 | |||

| Solo practice | 135 (35.9) | 106 (38.3) | 29 (29.3) | |

| Group practice | 234 (62.2) | 166 (59.9) | 68 (68.7) | |

| Others | 5 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (2.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Associated with an academic teaching center – n (%) | 0.04 | |||

| Yes | 133 (35.4) | 106 (38.3) | 27 (27.3) | |

| No | 241 (64.1) | 169 (61.0) | 72 (72.7) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Geographic region – n (%) | 0.98 | |||

| Northwest | 146 (38.8) | 108 (39.0) | 38 (38.4) | |

| Midwest | 88 (23.4) | 65 (23.5) | 23 (23.2) | |

| South | 93 (24.7) | 67 (24.2) | 26 (26.3) | |

| West | 48 (12.8) | 36 (13.0) | 12 (12.1) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Estimated patients seen in a typical week in primary setting – n (%) | ||||

| Responding physicians | 374 (99.5) | 275 (99.3) | 99 (100) | |

| Mean (SD) | 126 (84) | 124 (73) | 134 (109) | 0.39 |

| Median | 110 | 115 | 100 |

Optimistic physicians overestimated the actual percentage of their patients who were adherent by ≥10 points. All remaining physicians were considered non-optimistic.

Chi-square test (Fisher exact test if n < 5) was used for comparing categorical variables, Student t-test compared continuous variables between groups.

Pharmacy claims-based adherence compared to physician perceptions

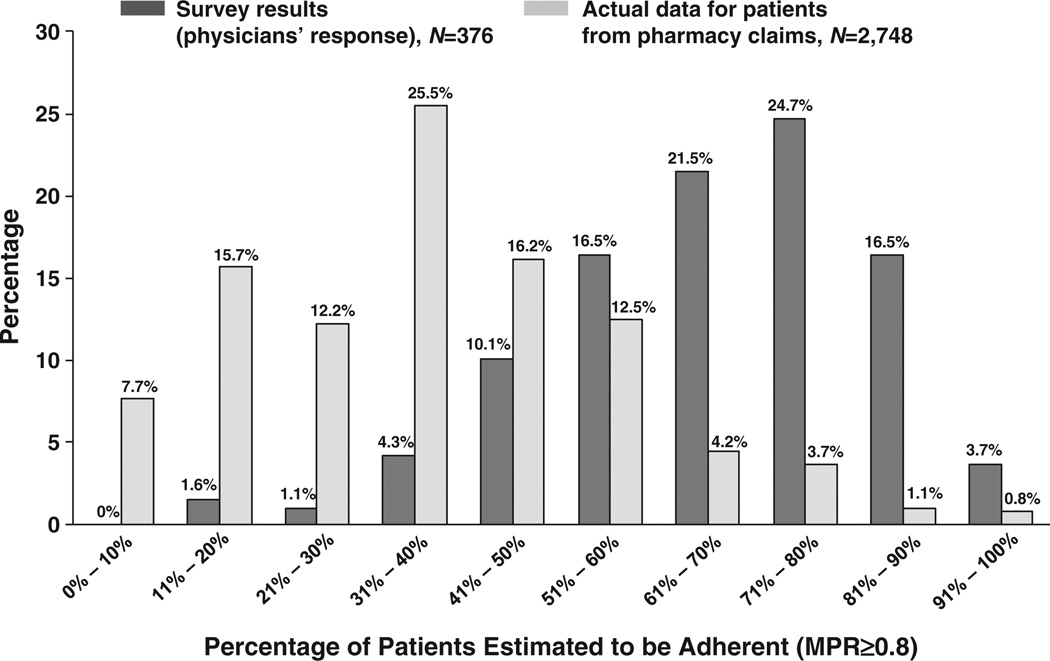

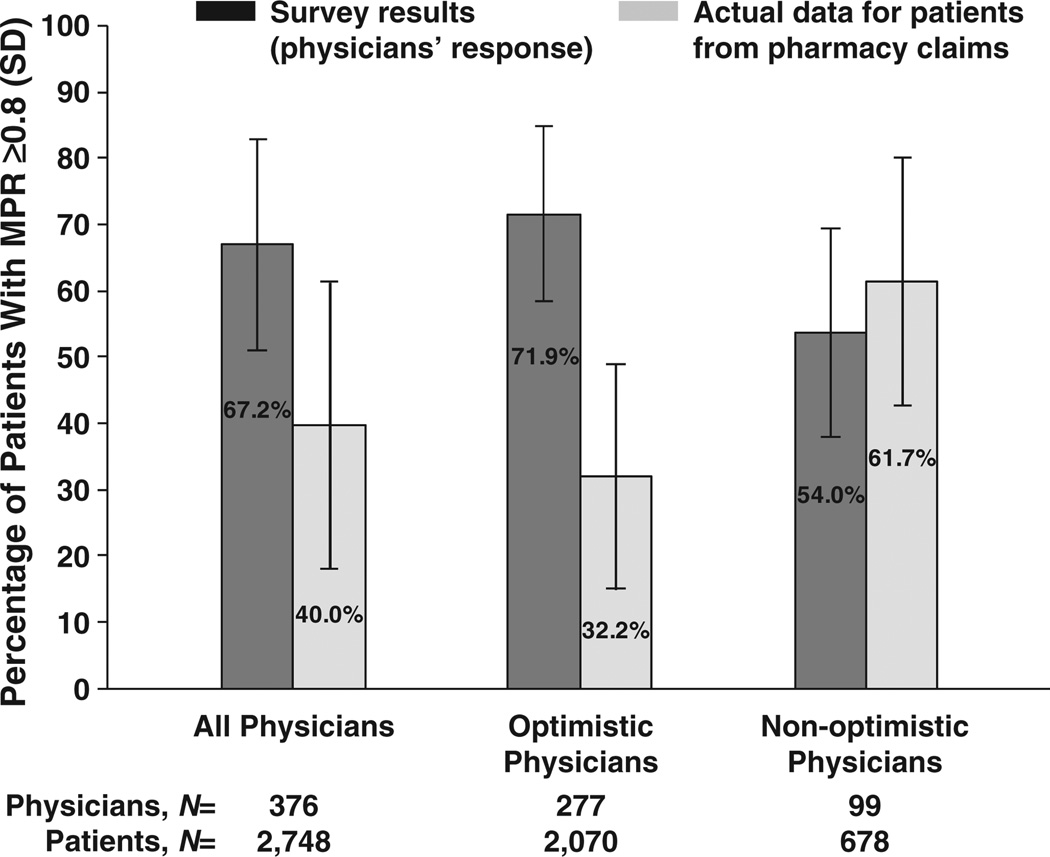

Physician estimates of adherence generally exceeded claims-based adherence (Fig. 1). On average, physicians estimated that 67.2% of their patients were adherent whereas 40.0% of these physicians' patients were adherent based on pharmacy claims data results (Fig. 2). A total of 73.7% of physicians were “optimistic” in their perception of adherence. Optimistic physicians (i.e., at least a 10% overestimation) on average overestimated the percentage of their patients who were adherent by 39.7 percentage points (71.9% vs. 32.2%)while non-optimistic physicians on average underestimated the percentage of their patients who were adherent by 7.7 percentage points (54.0% vs. 61.7%).

Fig. 1.

Osteoporosis medication adherence assessed by responding physicians and actual patient data from pharmacy claims.

Fig. 2.

Physician perceptions vs. actual patient data from pharmacy claims: estimated percentage adherent.

Side effects, medication cost, forgetfulness, lack of apparent benefit, and drug safety concerns were the most common reasons (ranked by percentage of survey participants) physicians reported for patient nonadherence to medication regimens (Table 3). A greater percentage of optimistic physicians than non-optimistic physicians reported affordability as a reason patients choose to adhere (34.7% vs. 23.2%, p = 0.04). Thus, this factor, along with physician demographic characteristics that differed between the two groups, was included in the logistic regression to assess predictors of optimistic estimation.

Table 3.

Physician-reported factors that influence adherence with osteoporosis medications (ranked by percentage of respondents)

| Percentage of respondents |

|

|---|---|

| Question: Please rank up to 5 factors (1 being most important) you believe would help motivate or increase patient adherence to prescription medication for the treatment of osteoporosis | |

| Lower cost of medication | 78.7 |

| Medication with fewer side effects | 75.3 |

| Less frequent dosing | 48.4 |

| More convenient dosing forms | 45.7 |

| Patient involvement in treatment | 43.1 |

| Question: Please rank up to 5 reasons (1 being the top reason) you believe patients do not adhere, meaning patients do not regularly take, their prescribed osteoporosis medication therapy | |

| Side effects of medication | 89.4 |

| Affordability of medication | 86.7 |

| Patient forgets to take medication | 70.2 |

| Results of medication are not apparent | 58.5 |

| Drug safety | 56.6 |

Results of the logistic regression analysis (Table 4) indicated that physicians in academic settings were more likely to be optimistic than community-based physicians (odds ratio [OR] 1.69, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.85). Physicians who stated that affordability was an important reason that patients choose to adhere were also more likely to significantly overestimate their patients' adherence (OR 1.80, 95% CI: 1.06, 3.09).

Table 4.

Logistic regression: physician characteristics associated with optimistic estimates of patients' adherence (N = 374)

| Characteristics of responding physicians that were significant in unadjusted comparisons |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Primary specialty | |

| General or family practice (reference group) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Internal medicine | 1.82 (0.94, 3.54) |

| OB/GYN | 0.90 (0.49, 1.65) |

| Other | 0.91 (0.40, 2.04) |

| Academic affiliation | |

| No (reference group) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Yes | 1.69 (1.01, 2.85) |

| Believe ‘affordability of medication’ is the reason that patients choose to adhere | |

| No (reference group) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Yes | 1.80 (1.06, 3.09) |

CI = confidence interval.

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit: 0.84, indicating adequate fit of the model.

Two physicians who did not respond to all included questions were excluded from this analysis.

Follow-up intervals

Nearly one-third (30.9%) of surveyed physicians recommended a 3-month interval for the next follow-up appointment, 24.3% recommended a 4- to 6-month interval, and 24.8% recommended an interval ≥6 months. According to the claims data, 2353 (85.6%) study patients visited their prescribing physician in the 12-months post-index. For those patients with a follow-up visit, the median interval between the medical or pharmacy claim just prior to or on the index date for the prescribing physician and the first post-index visit was 53 days (inter-quartile range [IQR] = 73 days). The median follow-up interval was 53.5 days for patients of academic physicians and 52.0 days for patients of community-based physicians (p = 0.2885). The mean (95% CI) number of visits with the prescribing physician during the 12-months post-index was 5.6 (95 % CI: 4.9, 6.3) for patients of academic physicians and 6.2 (95% CI: 5.7, 6.7) for patients of community-based physicians.

Most physicians reported that they monitored their osteoporosis patients by using repeat dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning (83%), asking patients about their adherence (95%), asking patients about problems with their medications (83%), and monitoring medical or pharmacy records for indications of ongoing refills (37%).

The majority of respondents believed that notices to alert physicians when patients have missed or delayed refilling would be somewhat or very useful (51% and 20%, respectively). Fewer physicians reported that health plan-generated reminders to patients would be somewhat or very useful (36% and 7%, respectively).

Discussion

Medication nonadherence is a critically important issue associated with nearly all chronic illnesses, but relatively little is known about how accurately physicians perceive their patients' adherence to osteoporosis medication regimens. Although our finding that physicians tended to overestimate their patients' adherence may not be surprising, to our knowledge this is one of the first studies to quantify the differences between perceived and actual levels of adherence for osteoporosis patients. On average, prescribing physicians in our sample estimated that 67% of their postmenopausal osteoporosis patients were adherent during the first year on therapy. Pharmacy claims, however, showed that only 40% of their patients in the study cohort were adherent. Our analyses also indicated that physicians in academic settings were more likely to overestimate adherence than community-based physicians.

Our results are consistent with the limited published literature, which reports that physician perceptions of osteoporosis adherence often exceed actual and patient-reported adherence,[20,21] and improve upon previous studies by directly comparing each physician's perception with actual adherence among his or her own patients. Although our study does not address the issue of primary nonadherence (i.e., patients who do not fill the initial prescription), our findings suggest that many physicians may be unaware of, and therefore unable to address, nonadherence that occurs after the initial prescription is filled. Physicians in our sample reported a very high rate of asking patients about adherence and problems with their medication, while overestimating the percentage of adherent patients. This may in part reflect physicians' reliance on asking patients whether they are continuing to take their medications rather than determining if the patient is taking the appropriate number of doses at the appropriate intervals. Focusing solely on this aspect of medication taking behavior, however, may lead to an overestimation of medication use. In our sample, for example, approximately 15% of the patients who were still on medication at 1 year filled their medications erratically and had MPR <0.8. For this reason, it appears advisable for physicians to probe beyond simply asking whether the patient is continuing to take the medication in order to understand a patient's refill patterns and to confirm compliance with recommended dosing instructions (e.g., taking a bisphosphonate on an empty stomach). One potential mechanism to enable physicians to independently assess adherence is to use pharmacy database links to electronic medical record systems that provide real-time information about medication refill patterns at the point of care.

Reasons reported by physicians for patient nonadherence and factors they believed were likely to contribute to improve adherence were also explored in this study. The top reasons (ranked by percentage of respondents) physicians reported for patient nonadherence with osteoporosis medications were medication side effects and affordability. Physicians also reported that availability of medication with lower costs, fewer side effects, and less frequent/more convenient dosing would increase adherence. Patients have reported that fear of side effects (not necessarily the actual experience of side effects) [22–26], lack of perceived benefits and insufficient awareness of disease-related consequences [20,26,27], and inconvenient or complex dosing requirements [20,26,28–32] influence adherence. A recent literature review noted that side effects, drug effectiveness, and mode of administration influence adherence with osteoporosis medications to a greater degree than dosing frequency [33]. To some degree, the factors that physicians in our sample perceived as important align with the adherence literature. However, when physicians misperceive the relative importance of these various factors, they may fail to spend adequate amounts of office visit time with patients discussing the most important issues that influence their patients' adherence, and providing closer follow-up of adherence. The challenge may be in finding ways to quantify and effectively communicate the risks and benefits associated with the prescribed medication so that patients better understand the potential impact of nonadherence. Improvements in patients' understanding of the consequences of the disease and of the trade-offs associated with therapy should lead to improved medication adherence and increased therapeutic benefit.

Office visits provide opportunities for physicians to assess their patients' adherence, increase patients' understanding of the benefits of therapy, discuss relevant test results, and help patients address side effects and other medication-related concerns — activities which have been correlated with improved adherence [11,12,34]. These studies suggested that patient adherence to osteoporosis medication might improve if physicians spent more time explaining the medication benefits and side effects. The quality of these patient–physician interactions (the extent to which the visit met patient expectations, satisfaction with the relationship, and overall satisfaction with the interaction) has also been shown to have a significant effect on adherence [35]. In addition to overestimating adherence as reported here, it is possible that some physicians overestimate the amount, quality (patient understanding of physician questions and instructions), and actionable content of the doctor–patient interactions may also influence physician perceptions of patient medication use. Although more research is needed to understand possible explanations, it is clear that there is a gap between physician understanding of patient nonadherence and actual patient behavior.

Our results suggest that most physicians (55.2%) recommended following up with patients within 3 to 6 months after initiating osteoporosis therapy. The majority (85.6%) of patients in our sample visited their prescribing physicians at least once during the 12 months after their initial osteoporosis medication fill. The median follow-up interval was just under 2 months and was similar for patients of academic and community-based physicians. While this result is consistent with the recommended follow-up interval, this finding also suggests that a considerable proportion of patients were not being seen by their prescribing physicians in the time period considered optimal. Furthermore, since the risk of medication-related side effects and therapy discontinuation is higher in the early months of therapy [36], these physicians may be missing opportunities to discuss and address side effects, clarify instructions regarding dosing, and educate patients on the benefits of osteoporosis medications. In other words, if patients have no follow-up visits or longer follow-up intervals, physicians have fewer opportunities to exhibit the supportive behaviors that the majority reported providing for their osteoporosis patients.

The findings of this study are subject to inherent limitations. On the physician survey, we chose to use the term“adherence” to include both the concept of persistence (duration of therapy) and compliance (doses taken as prescribed), in an effort to promote consistency between the physician responses and the calculation of MPR. We acknowledge that results may have differed if we had used the terminology recommended by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomic and Outcomes Research [37]. In an effort to include a broad spectrum of physicians (rather than just high-volume prescribers), we required that each participating physician have ≥5 patients in the study cohort. Results may have differed if only high-prescribing physicians were surveyed. Generalizability may be limited by the relatively low response rate for the physician survey, and by the fact that the sampling methodology relied on identification of women enrolled in a commercial health plan who filled ≥1 prescription for an osteoporosis medication. These patients may not be representative of all postmenopausal osteoporosis patients, e.g., those who received prescriptions but never filled them or those insured through other types of plans such as Medicare or Medicaid. Patients in the study cohort may comprise a minority of their prescribing physician's patient population, which may account for some of the observed differences between physician estimates of adherence levels and adherence calculated from pharmacy claims for patients in the study cohort. Furthermore, physicians' assumptions about copayment levels and pharmacy benefits structures for their practice overall may have influenced their estimates of adherence levels, and their assumptions may have differed from the actual benefits structures that applied to their patients in the study cohort. In addition, as is typical for pharmacy claims studies, we credited patients for the full days supply for each prescription fill which may result in overestimating the actual medication use. On the other hand, samples or medication obtained through sources outside of the health plan were not considered, which could lead to underestimation of the MPR.

In summary, physicians may be in a unique position to support their patients in achieving adherence with osteoporosis medications. However, we found that physicians tended to overestimate patient adherence. This overestimation may impede physicians' ability to recognize and address problems patients have in achieving high adherence with medication regimens. Physician beliefs about the chief impediments to adherence also appeared to differ somewhat from the patient's perspective. Increasing physicians' awareness of their patients' pharmacy claims-based adherence may enhance physician–patient communication regarding medication adherence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank David Macarios and Claire Merinar (Amgen Inc.) for contributions to the study design, Julie Brown (RAND) for assistance in designing the questionnaire, and Stacey Yager,Amanda Yu, and Rakesh Luthra (HealthCore Inc.) for assistance with data analysis. We would also like to thank Yeshi Mikyas (Amgen Inc.) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding source: This study was funded by Amgen Inc. whose employees and consultants collaborated in designing the study, analyzing and interpreting the data, and writing the manuscript. All listed authors approved submission of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement: BSS, AB, JDK, and HNV are employees of and have stock ownership in Amgen Inc. SWW and JLA are consultants to Amgen Inc., and have received remuneration for participation in this study. QC is an employee of HealthCore Inc., which received a grant from Amgen Inc. to conduct the research. JRC receives support from the NIH (AR053351) and AHRQ (R01HS018517) and is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Amgen Inc., and Roche, and has conducted research for Amgen Inc., Roche, Merck, and Eli Lilly.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey R. Curtis, Email: jcurtis@uab.edu.

Qian Cai, Email: ccai@healthcore.com.

Sally W. Wade, Email: sally.worc@gmail.com.

Bradley S. Stolshek, Email: Stolshek@amgen.com.

John L. Adams, Email: johnlloydadams@gmail.com.

Akhila Balasubramanian, Email: akhilab@amgen.com.

Hema N. Viswanathan, Email: hemav@amgen.com.

Joel D. Kallich, Email: jkallich@bighealthdata.net.

References

- Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17:25–54. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c617e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2007;297:387–394. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM, Bauer DC, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Lewis CE, Barrett-Connor E, Cummings SR. High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA. 2007;298:2381–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colon-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:380–390. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen MD, Keam SJ. Denosumab: a review of its use in the treatment of postmen-opausal osteoporosis. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:63–82. doi: 10.2165/11203300-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PREMARIN® (conjugated estrogens tablets, USP) Available at: http://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabelingaspx?id=131. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher SW, Colditz GA. Failure of estrogen plus progestin therapy for prevention. JAMA. 2002;288:366–368. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE. Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens. 2002;20(Suppl):S62–S65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgstrom F, Herings RM, Silverman SL. Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med. 2009;122:S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookhart MA, Avorn J, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS, Arnold M, Polinski JM, Patrick AR, Mogun H, Solmon DH. Gaps in treatment among users of osteoporosis medications: the dynamics of noncompliance. Am J Med. 2007;120:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–1460. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DT, Silverman S. Review of adherence to medications for the treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2006;4:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11914-006-0011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud K, Tosteson AN, Varon SF, Anthony M, Daizadeh N, Wade S. Design of the POSSIBLE UStrade mark Study: postmenopausal women's compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga MM, Bleich SN, Beach MC, Clark JM, Cooper LA. Disparity in physician perception of patients' adherence to medications by obesity status. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1932–1937. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot L, Couris CM, Tainturier V, Jaglal S, Colin C, Schott AM. Trends in HRT and anti-osteoporosis medication prescribing in a European population after the WHI study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1047–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LG, Liu H, Hays RD, Golin CE, Beck CK, Asch SM, Ma Y, Kaplan AH, Wenger NS. How well do clinicians estimate patients' adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.09004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wens J, Vermeire E, Royen PV, Sabbe B, Denekens J. GPs' perspectives of type 2 diabetes patients' adherence to treatment: a qualitative analysis of barriers and solutions. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huas D, Debiais F, Blotman F, Cortet B, Mercier F, Rousseaux C, Berger V, Gaudin AF, Cotte FE. Compliance and treatment satisfaction of post menopausal women treated for osteoporosis. Compliance with osteoporosis treatment. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copher R, Buzinec P, Zarotsky V, Kazis L, Iqbal SU, Macarios D. Physician perception of patient adherence compared to patient adherence of osteoporosis medications from pharmacy claims. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:777–785. doi: 10.1185/03007990903579171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteoporosis treatment options expand. Mayo Clin Health Lett. 2010;28:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgener M, Arnold M, Katz JN, Polinski JM, Cabral D, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Older adults' knowledge and beliefs about osteoporosis: results of semistructured interviews used for the development of educational materials. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:673–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickney CS, Arnason JA. Correlation between patient recall of bone densitometry results and subsequent treatment adherence. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1156–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di Munno O, Giannini S, Minisola S, Sinigaglia L, Adami S. Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:914–921. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Hammond CS, Moncur MM, Ray GT, Hebert GM, Pressman AR, Ettinger B. Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NH. Compliance with treatment regimens in chronic asymptomatic diseases. Am J Med. 1997;102:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B, McCoy K, Taggart H. Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:259–262. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler D, Kung AW, Fuleihan Gel H, Gonzalez Gonzalez JG, Gaines KA, Verbruggen N, Melton ME. Patients with osteoporosis prefer once weekly to once daily dosing with alendronate. Maturitas. 2004;48:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE. Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:856–861. doi: 10.4065/80.7.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JA, Lewiecki EM, Smith ME, Petruschke RA, Wang L, Palmisano JJ. Patient preference for once-weekly alendronate 70 mg versus once-daily alendronate 10 mg: a multicenter, randomized, open-label, crossover study. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1871–1886. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M, Vered I, Foldes AJ, Cohen YC, Shamir-Elron Y, Ish-Shalom S. Treatment preference and tolerability with alendronate once weekly over a 3-month period: an Israeli multi-center study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:143–149. doi: 10.1007/BF03324587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Glendenning P, Inderjeeth CA. Efficacy, side effects and route of administration are more important than frequency of dosing of anti-osteoporosis treatments in determining patient adherence: a critical review of published articles from 1970 to 2009. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:741–753. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R. The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1117–1123. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor–patient communication. Patients' response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535–540. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196903062801004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Xi J, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E. Improving the prediction of medication compliance: the example of bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Med Care. 2009;47:334–341. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818afa1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.