Abstract

Aims:

To describe socio-demographic characteristics, psycho-social factors, psychiatric co-morbidity in hundred completed suicide victims.

Materials and Methods:

A detailed interview was carried out with family members of suicide victims using psychological autopsy questionnaire.

Results:

Males committed suicide significantly more often than females. The most common age group was 30-44 years, followed by 15-29 years. Most of them were married (68%) and majority (78%) had education less than 10th standard. Psychiatric morbidity was found in 94%, depression being the most common diagnosis (54%), followed by alcohol use disorders (42%). 40% of the victims had contact with mental health services and 50% with general health services in the 3 months preceding suicide.

Conclusions:

The rate of suicide is high in middle age and a very significant proportion of these suffer from diagnosable psychiatric disorders. Many of the suicide completers visit health services in the preceding few months of the event. In prevention of suicides, health professionals, both mental and general, can play a major role.

Keywords: Health services, psychiatric co-morbidity, suicide

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is defined as the human act of self-inflicted and self-intentional cessation of life. The nature of suicidal phenomenon is complex and the study of suicide even tougher as the person who has committed suicide is no longer available for psychological examination. The family already been stigmatized by the unfortunate event is not very forthcoming and not easily approachable. The description, both subjective and objective, is most likely to be colored by factors like the presence of psychiatric morbidity, overall effect of it on the relative who furnishes the data, fear of information being leaked out, etc., Thus, a true representation may not be obtained. Suicide's legal and social consequences lead to underreporting. The suicidal acts are associated with diagnosable psychiatric disorders and can be triggered by acute stress, shame, cult behavior, or various other reasons. Litman et al. were pioneers in using the psychological autopsy as a process to study the correlates of completed suicide.[1] It has been studied and published that diagnoses obtained from psychological autopsy are reliable, valid, and unaffected by bereavement. The acceptance rate was high (77.1%).[2]

The global average of suicide rate is 14.2 per lakh per year and the current national rate of suicide is 11.4 per lakh per year.[3] The highest suicide rate in the world has been reported among women in South India in the 15-19 years age group.[4] The number of suicide cases in India has been consistently on the rise every year. During the decade 2001-2010, the number of suicides in the country has recorded an increase of 23.9% as against the population, which had a growth rate of only 18.3%. An increasing trend in the suicide rate is observed during the period from 2006 to 2010.

Goa ranks 11th in the union of Indian states, with the recorded suicide rate of 18.5 per lakh per year.[3] The number of cases of suicides is on the rise and is an issue of major concern for those who come to face the brunt of the problem, including psychiatrists.

Hence, the present study was undertaken to investigate suicide cases with the following aims and objectives:

To describe socio-demographic characteristics of individuals with completed suicides

To obtain family members’ description of psychological history of suicide completers

To assess if victims sought medical or psychiatric help prior to suicide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The data were collected from the police department of the state at various levels, i.e., from police stations and the readers’ branches (police sub-department which maintains some details of the data), from the year 2001 to 2006. To draw a sample of hundred cases of suicide, every fifth reported case of suicide in the years 2005-2007 was included in the study. When refusal was encountered or family of suicide victim could not be traced, the next reported case was included. Seventeen families refused to take part in the study and relatives of four suicide victims could not be traced. The information pertaining to the occurrence of suicide and whereabouts of the family of suicide victim was obtained from the state police department and the leading daily newspapers’ offices. The family of the suicide victim was visited by the interviewer directly within 30-60 days after the suicide, which is similar to that in most of the Indian studies but shorter than that mentioned in western studies. Informed consent was obtained prior to interview. A detailed interview was carried out using psychological autopsy questionnaire (semi-structured questionnaire based on ICD-10). It includes a life events scale to establish life events in victim's life prior to the act of suicide. The number of family members present during the interview was two to four. The key informant in most cases was spouse followed by mother. The average time taken for interview was in the range of 3-4 h. A Konkani version of the questionnaire developed and standardized by the author was used for the families where English version could not be used for any reason. The data were analyzed to present suicide and its relationship with various socio-demographic variables, mental illness, significant family history, and contact with general practitioner and psychiatrist. The data were analyzed using Chi-square test and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The information regarding presence of psychiatric illness in the family members was collected from informants and based on whether a member is suffering from psychiatric illness of any type and taking treatment for the same.

RESULTS

The data of completed suicides in the state of Goa were studied for the years 2001-2006, and the completed suicide cases showed the following demographics. The proportion of males committing suicide was significantly higher than females, with male to female ratio of almost 70:30. Most suicides occurred in the ages between 15 and 44 years, with age groups 15-29 and 30-44 years having almost equal distribution. Most of the victims were married (53.1%), while unmarried victims constituted 39.5%. Among the completed suicide victims, 22% were illiterate, 48% had attained primary education, 30% had studied up to secondary level, and only 8% had level of education of higher secondary or more. Hanging was the most commonly adopted mode (44%), followed by poisoning (20%) and drowning (18.7%).

In this study sample of 100 cases, males (70%) committed suicide more often than females (30%) (P<0.01). The number of suicides was highest in the age group 30-44 years (42%) (P>0.001). The most vulnerable age groups were different in males and females. The most common age group among male suicide victims was 30-44 years (45.7%), and among females, the vulnerability in the age groups 15-29 years and 30-44 years was comparable. The results concerning marital status of suicide victims show that majority of the victims were married (68% vs. 32%; P<0.05). The association was stronger in the female gender. Majority of suicide victims had not attained higher levels of education. 78% of victims had education less than 10th standard (P<0.001). 40% of the male suicide victims were unemployed, suggesting that unemployment was an important contributing factor for suicide in males. There was higher risk of suicide in people living in urban areas than in rural areas (64% vs. 36%; P<05).

Overall, hanging (46%) was the most common means adopted by suicide victims (P<0.001). Hanging was also the most common means adopted for suicide by male victims (60%), while poisoning was the most common means adopted among female victims (40%).

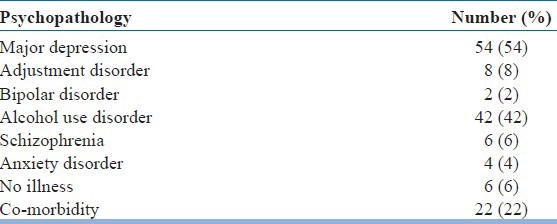

Psychiatric morbidity among suicide victims was high. 94% had at least one psychiatric illness (P<0.001). Major depressive disorder was the most common diagnosis (54%), followed by alcohol use disorders (42%). Co-morbidity was found in 22% of cases. Major depressive disorder and alcoholism were the most common co-morbid diagnoses [Table 1].

Table 1.

Psychiatric morbidity among suicide victims

Recent life events were present in 86% of suicide completers (P<0.001). Adolescents had difficulties with regards to their education, especially failure in exams. Among middle-aged men, economic problems were the main stressors, while among women it was interpersonal conflicts and rejections. Medical ailments were found to be present in 26% of suicide victims, significantly more common in elderly. 58% of suicide completers had past history of suicidal attempt. 40% of suicide completers had family history of mental illness (CI 30.40-49.60) and 16% had history of suicide in family members (CI 8.82-23.19).

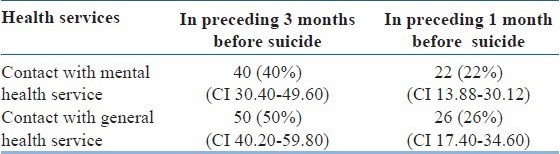

40% of the suicide victims had contact with the mental health services and a greater number (50%) had contact with general health services (general practitioners) in the preceding 3 months before suicide [Table 2].

Table 2.

Suicide victims’ contact with mental and general health services

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to analyze suicides in the state of Goa, which is an issue of increasing public concern in the state. It has been studied and published that diagnoses obtained from psychological autopsy are reliable and valid.

The data of total number of suicides in the state of Goa over 6 years, i.e., from 2001 to 2006, reveal that males commit suicide more often than females (2-2.5 times). This study shows that men commit suicide 2.3 times more often than women, which is marginally higher than that reported in Indian literature by Suresh Kumar (2004),[5] Shukla (1990),[6] and Nandi (1979).[7] Over the 6-year period, the number of suicides was highest in the age group 30-44 years. In this study, the most vulnerable age groups were different in males and females, as also reported earlier by Henriksson (1993).[8] The most vulnerable age group overall was 30-44 years, which was also the most common age group among male suicide victims, but among females, 15-29 years age group was the most vulnerable. Vijayakumar (1999)[9] in her study reported most of the suicides in the age group 20-29 years, and Conwel (1996)[10] too reported the rate to be high in young to middle age. The mean age of suicide victims in this study was 36 years, which is lesser than that reported earlier by Baxter and Appleby (1999).[11] Thus, one concludes that suicide is now becoming a more common cause of death among younger population than middle age. This is also in line with World Health Organization (WHO) report of 2001.[12] The lower prevalence of suicide among population of 50 years and above in our population could be attributed to the fact that in our culture, the aged continue to be integrated and respected in the family. Another factor could be the lower life expectancy of our population compared to that of western societies, and so our population itself is eschewed in favor of the young.

The results concerning marital status of suicide victims over the 6-year period showed that majority (i.e., 53%) were married, whereas only 39% were unmarried. The results of our study also bring out the same fact that majority (i.e., 68%) were married, whereas only 32% were unmarried. The association was stronger in the female gender. The findings were similar to earlier Indian studies by Hegde (1980),[13] Shukla (1990),[6] and Suresh Kumar (2004),[5] and were contrary to those of western authors like Heinkkinen (1995),[14] Appleby (1999),[15] and Castle (2004).[16] The reasons for the same are several. The institution of marriage is more deeply ingrained in Indian culture than the west. Marital partners are virtually strangers to each other (due to arranged marriage), and so are the families. Hence, several adjustment problems could arise among married couples and their families, especially if mental illness is present in either partner. Divorce being socially frowned upon, suicide provides the only escape. This calls for measures to cultivate and improve upon coping style to face adjustment problems in married life. Family and couple therapy can play a major role.

Majority of suicide victims had not attained higher levels of education. It is observed that in 6 years’ suicide population, majority of suicide victims had not attained higher levels of education. Less than 30% had education above primary level and barely 8% had higher secondary education or more. In the study sample, 78% of victims had education less than 10th standard. Castle (2004)[16] reported that only 17% of suicide completers had studied up to college level. Persons having higher education possibly have better stress-handling and coping skills. There is in them comparatively better-developed social network and they have better knowledge of and access to health care. Therefore, provision of higher education may bring down the increasing number of suicides in the state.

Unemployment was an important contributing factor for suicide in males. King (1994),[17] Hawton (1988),[18] Cheng (2000),[19] Gupta (1992),[20] Ponnudurai (1997),[21] Venkoba Rao (1977),[22] and Nandi (1978)[23] gave similar observation.

Overall, hanging was the most common means adopted by suicide victims, seen in 44% of them over the six consecutive years (2001-2006). Among the sample of hundred suicide completers studied, 46% adopted hanging as means to commit suicide while 22% contributed each by poisoning and drowning. Hanging was also the most common means adopted for suicide by male victims, while poisoning was the most common means adopted among female victims. The results parallel those reported earlier by Henrikkson (1993),[8] Vijayakumar (1999),[9] and Hawton (1999).[24] Hanging as means adopted for suicide indicates a stronger suicidal intention, which led victims to choose more lethal and sure means to commit the act. Females have limited mobility outside home and have more accessibility to drugs, poison, kerosene, etc., and therefore adopt poisoning as the most common means for suicide.

The high levels of stress and inability to adjust with rapidly changing and demanding needs of urban life may be contributing to the high percentage of suicide victims in urban areas, as reported in this study.

In the study sample of hundred victims, psychiatric morbidity was found to be high among the suicide victims. 94% of victims were suffering from at least one psychiatric illness at the time of death. Various authors like Robbins (1959),[25] Barraclough (1997),[26] Baxter (1999),[11] and Kessing (2004)[27] have reported the presence of psychiatric illness in majority of suicide completers, the percentage ranging from 81% to 100%. Almost all the studies have found affective disorders to be the most common diagnosis among suicide completers. In our study, major depressive disorder was the most common diagnosis (54% of suicide completers), and if adjustment disorder and bipolar depression were taken along with major depressive disorder, the depressive syndrome made up 64% of suicide victims. Therefore, the need to ascertain and treat even mild to moderate depression becomes apparent. This should be one of the important strategies in the suicide prevention programs. The second most common area that needs attention is alcohol use disorders, which is the diagnosis among 42% of suicide victims in our study. Co-morbidity was found in 22% of cases. Major depression and alcoholism were the most common co-morbid diagnoses. Henriksson (1993),[8] Vijayakumar (1999),[9] Hawton (1988),[18] and Foster (1999)[28] have reported co-morbidity in 30-50% of suicide victims.

Rich (1991)[29] and Vijayakumar (1999)[9] found psychosocial stressors and life events in virtually all cases of suicide. Recent life events were present in 86% of suicide completers in our study.

Medical ailments were found to be present in 26% of suicide victims, significantly more common in elderly. Long duration illnesses like diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac ailments were more common. Inadequate support was a source of stress for elderly.

Suicidal ideation of yesterday is highly likely to become the suicide threat or attempt of today or completed suicide of tomorrow. Appleby (1999),[15] Vijayakumar (1999),[9] Hawton (2003),[30] and many others have reported high incidence of suicide attempts in suicide victims, ranging from 21% to 68%. In our sample, 58% of suicide completers had past history of suicidal attempt. This fact should guide us to assess patients in detail for the presence of any suicidal ideation, behavior, or communication, in the present or past, as important risk factor for eventual suicide and even the minimal of risk should be dealt with seriously and aggressively.

A strong family history of psychopathology and suicidal behavior has been reported in suicide victims by Vijayakumar (1999),[9] Barraclough (1997),[26] Gupta (1992),[20] and Ponnudurai (1997).[21] In our sample, 40% of suicide completers had family history of mental illness and 16% had history of suicide in family members. Probably familial psychopathology endows genetic vulnerability, decreases social support, and increases distress at home, thereby increasing the risk of suicide.

King (1994),[17] Gunell (1994),[31] and Foster (1999)[28] have reported that almost 90% of suicide victims were in contact with general practitioner at the time of death and about half of them were in contact with mental health services in the preceding 3 months. 40% of the suicide victims in our sample had contact with the mental health services in the preceding 3 months and 22% in the preceding month before suicide. A greater number (50%) had contact with general health services (general practitioners) in the preceding 3 months before suicide. Hence, a significant number of suicide victims make contact with or communicate their suicidal thoughts to general or mental health personnel. It indicates that if an action was taken in time, it might have prevented suicidal deaths. Therefore, it is also imperative that we consider every suicidal communication, verbal or nonverbal, seriously and act immediately. Educating and sensitizing the general practitioners about signs and symptoms of various psychiatric illnesses, especially mood disorders, their management, and if required early referral, will be beneficial.

The prevention of suicide still continues to be a major challenge to the field of psychiatry. Our progress in this area will depend on the amount of effort and research we put in toward understanding suicides.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Litman RE, Curphey T, Schneidnan ES. Investigations of equivocal suicide. J Am Med Assoc. 1963;184:924–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly TM, Mann J. Validity of DSM III-R diagnosis by psychological autopsy: A comparison with clinician ante mortem diagnosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:337–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Crime Records Bureau. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya S. Indian teens have world's highest suicide rate. Lancet. 2004;363:1117–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suresh Kumar PN. An analysis of suicide attempters versus completers in Kerela. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:144–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla GD, Verma BL, Mishra DN. Suicide in Jhansi city. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Banerjee G, Ghosh A, Horal GC, Choudhary A, et al. Is suicide preventable by restricting the availability of lethal agents? A rural survey of West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;21:251–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Kuoppasalmi KI, et al. Mental disorders and co-morbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:935–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayakumar L, Rajkumar S. Are risk factors for suicide universal? A case-controlled study in India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:407–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conwel Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED. Relationship of age and axis I diagnosis in victims of completed suicide: A psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1001–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter D, Appleby L. Case register study of suicide risk in mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:322–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geneva: WHO; 2001. WHO- Report on suicide prevention: Emerging from darkness. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hegde RS. Suicide in rural community. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:368–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Marttunen MJ. Social factors in suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167:747–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.6.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appleby L, Cooper J, Amos T, Faragher B. Psychological autopsy study of suicide by people aged under 35. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:168–74. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castle K, Duberstein PR, Meldnum S, Conner KR, Conwel Y. Risk factors for suicide in Blacks and Whites: An analysis of data from the 1993 National Mortality follow back survey. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:452–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King E. Suicide in mentally ill. An epidemiological sample and implications for clinicians. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:658–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawton K, Fogg J. Other causes of death following attempted suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:359–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng AT, Chen TH, Chen CC, Jenkins R. Psychological and psychiatric risk factors for suicide: Case-control psychological autopsy study. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:360–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta SC. Suicide risk in depressives and schizophrenics. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:298–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponnudurai B. Suicide in India. Indian J Psychol Medicine. 1997;19:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venkoba Rao A. Suicide. J Indian Med Association. 1977;68:250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Borali GC. Suicide in West Bengal: A century apart. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;20:155–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawton K, Houston K, Shepperd R. Suicide in young people. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:271–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins E, Gassner S, Kayes J, Wilkinson RH, Jr, Murphy GE. The communication of suicidal intent: A study of 134 consecutive cases of successful (completed) suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 1959;115:729–33. doi: 10.1176/ajp.115.8.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris EC, Barraclough BM. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–28. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessing LV. Severity of depressive episodes according to ICD-10: Prediction of risk of relapse and suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:153–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster T, Gillepsie K, McClelland R, Patterson C. Risk factors of suicide independent of DSM III-R axis I disorder: Case-control psychological autopsy. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich CL, Warsradt GM, Nemiroff RA, Fowler RC, Young D. Suicide, stressors, and lifecycle. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:524–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatheall R. Suicide following self-harm: Long term follow up study of patients who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:537–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunnell D, Frankel S. Prevention of suicide: Aspirations and evidence. BMJ. 1994;308:1227–33. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6938.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]