Abstract

Context:

The design of safe clinical trials targeting suicidal ideation requires operational definitions of what degree of suicidal ideation is too excessive to allow safe participation.

Aims:

We examined the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) to develop a psychometric cut-point that would identify patients having a suicidal emergency.

Settings and Design:

The Emergency Department (ED) and the out-patient clinic of a university hospital.

Materials and Methods:

We used the SSI to contrast 23 stable, depressed adult out-patients versus 11 depressed adult ED patients awaiting psychiatric admission for a suicidal emergency.

Statistical Analysis:

The performance of the SSI was examined with nominal logistic regression.

Results:

ED patients were older than out-patients (P<0.001), with proportionally more men (P<0.05), and were more ethnically diverse than the outpatients (P<0.005). Compared to out-patients, ED patients were more depressed (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score 23.1±3.8 vs. 11.7±7.3, P<0.005) and reported a greater degree of suicidal ideation (SSI scores 25.7±7.3 vs. 4.2±8.4, P<0.0001). Nominal logistic regression for the univariate model of SSI score and group yielded a score of 16 (P<0.0001) as the best cut-point in separating groups, with a corresponding Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve = 0.94. Of 34 patients in the total sample, only two were misclassified by SSI score = 16, with both of these being false positive for ED status. Thus, the sensitivity of the cut-point was 100% with specificity of 91%. When the model was expanded to include SSI along with age, gender, ethnicity, sedative-hypnotic use, and over-the-counter use, only SSI score remained significant as a predictor.

Conclusions:

A SSI score ≥16 may be useful as an exclusion criterion for out-patients in depression clinical trials.

Keywords: Depression, emergency department, suicidal ideation

INTRODUCTION

In preparation for an out-patient clinical trial to reduce suicidal ideation, we developed a psychometric cut-point to identify depressed patients with emergent suicidal ideation needing Emergency Department (ED) services. In general, design of clinical trials for suicide risk-reduction faces both practical and ethical dilemmas. On one hand, there is the need to include patients with some degree of suicidal ideation while on the other hand there is a need to exclude patients with unmanageable risk. Thus, it would be useful to define a cut-point assisting in identifying emergent levels of suicidal ideation of patients that should be excluded from clinical trial participation.

We previously reported on the relationship between sleep distress and suicidal ideation.[1] In this secondary analysis, our goal was to devise a psychometric cut-point with good sensitivity and specificity and thus formulate an operational rule for an exclusion criterion for emergent suicidality for a clinical trial designed to reduce suicidal ideation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting and population

Inclusion criteria

Participants were sought from a convenience sample of psychiatric out-patients and psychiatric ED patients who were consecutively recruited over the calendar year 2011. Participants were literate, English-speaking adults ≥18 years old, with a chart diagnosis of one of the following depressive illnesses with nil, mild, moderate or a severe degree of overall symptoms: Major depressive disorder without psychotic features, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, depressive disorder not otherwise specified, bipolar disorder type I-most recent episode depressive or bipolar disorder type II-most recent episode depressive.[2] Out-patients were consented during a routine, follow-up out-patient visit for mood disorder, with the clinical judgment that the patient was sufficiently stable that their next follow-up visit would also be an out-patient visit. ED patients were being held in the ED for psychiatric admission, expressly because of suicidal ideation. Research staff explained the study to participants before obtaining written, informed consent. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with a primary sleep disorder (e.g., sleep apnea) or restless leg syndrome were excluded.[1,3] Patients with a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, cognitive disorder (dementia) or borderline personality disorder were excluded. Patients who had received electroconvulsive therapy in the last 30 days or who met criteria for substance abuse or dependence in the last 30 days were excluded. All ED patients had a negative blood alcohol and negative urine drug screen at the time of presentation.

Clinical assessment

Psychiatric physicians, including both residents and faculty, conducted all patient assessments. Physicians collected demographic and clinical information, including age, gender, education level, race, marital status, presence or absence of chronic pain, and number of prior clinical encounters (both inpatient and out-patient) within our Department of Psychiatry. In the absence of a structured diagnostic interview, physicians recorded the number of clinical encounters (cataloged in ranges: 1-5, 6-10, 11-15, 16+) to reflect the sum of our prior clinical experience with the patients as an indirect measure of confidence in the diagnosis. Psychiatric diagnoses were ascertained by a review of the entire electronic health record (EHR).

Physicians reviewed the EHR for all current medications and verified them with the participant. All psychotropic medications were permitted and were catalogued according to the following general categories, irrespective of dose:

Non-sedating antidepressants: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and bupropion

Sedating antidepressants: Trazodone, mirtazapine, tricyclic antidepressants

Antipsychotics: Typicals (e.g., haloperidol, fluphenazine, thiothixene) and atypicals (e.g., aripiprazole, zisprasidone, asenapine, quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone)

Mood stabilizers: Lithium, lamotrigine, valproate

Hypnotic/anxiolytics: Benzodiazepines, hydroxyzine, zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon

Over-the-counter (OTC) sleep aids: Melatonin, diphenhydramine, doxylamine.

Psychometrics

Physicians collected the following psychometrics on each patient:

Depression severity was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)[4]

The Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) is a well-validated instrument consisting of 19 items that evaluate three dimensions of suicide ideation: Active suicidal desire, specific plans for suicide and passive suicidal desire.[5,6] Each item is rated on a 3-point scale from 0 to 2 for a maximum score of 38 with a lower score indicating less severe suicidal ideation. Other investigators have found that a SSI score ≥3 predicts greater risk of suicide death over a time period of years.[7] The ascertainment of the SSI included a review of the patient's suicide attempt history.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics of continuous variables were calculated with means and standard deviations while discrete variables are presented as proportions. Differences in continuous variables between the out-patient and ED groups were tested by two-tailed t-tests. Between-groups differences in discrete variables were tested using Chi square analysis. Models to predict the out-patient status versus ED status were tested with logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic curves. A priori sample size calculations were not performed for this secondary analysis of this pilot study.

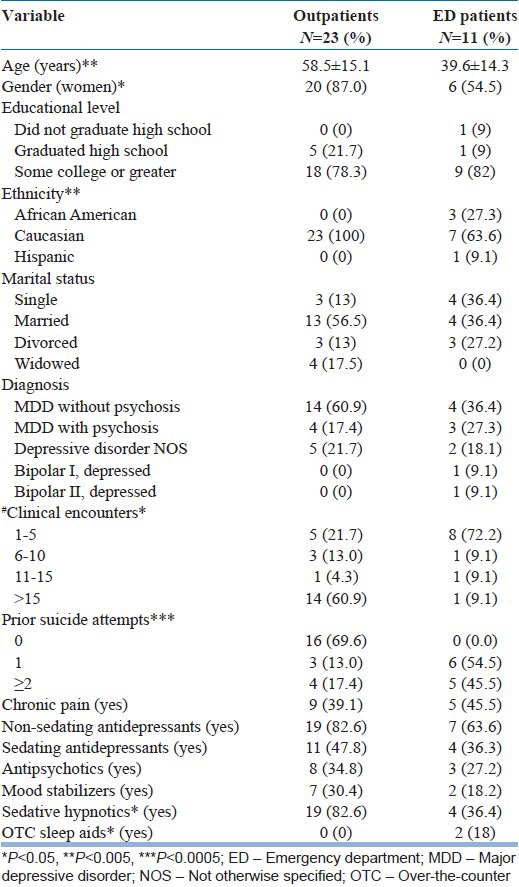

RESULTS

The sample included 23 outpatients and 11 ED patients. ED patients were younger than outpatients (t=2.0; df=32, P<0.001), with proportionally more men (χ2=4.1, df=1, P<0.05), and were more ethnically diverse than the outpatients (χ2=10.2, df=2, P<0.005). There were no significant differences in marital status, educational status or proportions of diagnoses. Compared with out-patients, ED patients had fewer prior psychiatric visits (χ2=10.8, df=3, P<0.05), were less likely to be receiving a sedative-hypnotic medication (χ2=7.1, df=1, P<0.01), but more likely to be taking an OTC sleep aid (χ2=4.7, df=1, P<0.05). The ED patients had made proportionately more suicide attempts than the out-patients (χ2=19.0, df=2, P<0.0001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

PHQ-9 total score was higher in the ED group (23.1±3.8) than in the out-patient groups (11.7±7.3) (P<0.005). SSI scores were higher in the ED patients (25.7±7.3) compared to the out-patient group (4.2±8.4) (P<0.0001).

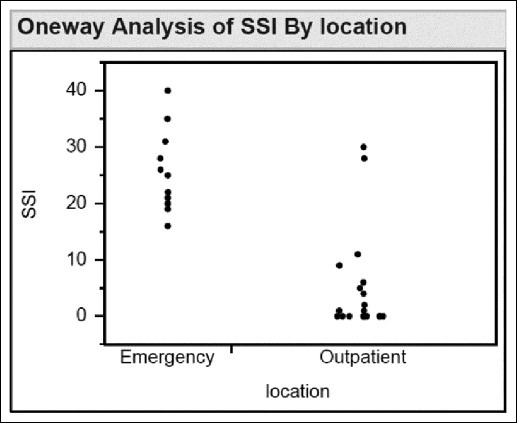

Creation of a ROC curve found that a SSI score of 16 maximized “sensitivity-(1-specificity)” with AUC=0.94 in predicting a patient's status as out-patient versus in the ED. Of 34 patients in the total sample, only 2 were misclassified by SSI score=16, with both of these being false positive for ED status [Figure 1]. Thus, the sensitivity of the cut-point was 100% with specificity of 91%. Nominal logistic regression for this univariate model yielded χ2=24.5, df=1, and P<0.0001. When the model was expanded to include the other variables, which were significantly different between out-patients and ED patients (age, gender, ethnicity, sedative-hypnotic use, and OTC use), only the SSI score remained significant as a predictor of ED versus outpatient status.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of scale for suicide Ideation scores according to patient locativon

DISCUSSION

A SSI score of 16 robustly separated stable, depressed out-patients from suicidal psychiatric ED patients. We had not anticipated the demographic differences between groups, but including age, gender, ethnicity, sedative-hypnotic use and OTC sleep aid use into a multivariate logistic regression did not change the inference that it is the SSI score that best predicts out-patient status versus ED status.

We do not recommend using our derived cut-point for SSI score as the sole criterion for patient inclusion or exclusion in clinical trials of suicide risk reduction, but it might serve as the initial guide. The principal value of having psychometric cut-points for inclusion into clinical trials of suicidal ideation is to provide a minimum “floor” for safety as well as to provide some degree of consistency in how participants are handled across sites in multi-site studies of suicide risk reduction.

This study has several limitations. The first is that the sample was collected at one site, and different results might be obtained at other sites with different risk assessment and admission practices. Second, the sampling technique was a convenience sample, which led to unanticipated inter-group imbalances in demographics. Although these imbalances were managed as co-variates in multivariate modeling, matching group enrollment on the basis of demographics would have been preferable. A third limitation is the wide, but uneven use of psychotropic medications, which may have unpredictable effects on suicidal ideation. While it is conceivable that data could have been collected on medication-free outpatients, it seems unlikely that medication-free status could be achieved for ED patients. A fourth limitation is the ascertainment of diagnosis by chart review and PHQ-9 definitions. A structured interview for diagnosis would be preferred. A fifth limitation is the small size sample.

In conclusion, a SSI score ≥16 powerfully discriminated between stable psychiatric outpatients being treated for depression versus psychiatric patients in an ED being held for admission for suicidal ideation. A SSI score ≥16 may be useful as an operating rule to exclude patients from clinical trials who are at excessive risk of suicide. These results need to be prospectively validated on other settings.

Footnotes

Source of Support: NIH award 1 R01 MH095776-01

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.McCall WV, Batson N, Webster M, Case LD, Joshi I, Derreberry T, et al. Nightmares and dysfunctional beliefs about sleep mediate the effect of insomnia symptoms on suicidal ideation. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:135–40. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–19. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:1039–46. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:371–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]