Abstract

Pleckstrin homology (PH) domains represent the 11th most common domain in the human proteome. They are best known for their ability to bind phosphoinositides with high affinity and specificity, although it is now clear that less than 10% of all PH domains share this property. Cases in which PH domains bind specific phosphoinositides with high affinity are restricted to those phosphoinositides that have a pair of adjacent phosphates in their inositol headgroup. Those that do not (PtdIns3P, PtdIns5P and PtdIns(3,5)P2) are instead recognized by distinct classes of domains including FYVE domains, phox homology (PX) domains, PHD fingers, and the recently identified PROPPINs. Of the 90% of PH domains that do not bind strongly and specifically to phosphoinositides, few are well understood. One group of PH domains appears to bind both phosphoinositides (with little specificity) and Arf family small G-proteins, and are targeted to the Golgi apparatus where both phosphoinositides and the relevant Arfs are both present. Here, the PH domains may function as coincidence detectors. A central challenge in understanding the majority of PH domains to establish whether the very low affinity phosphoinositide binding reported in many cases has any functional relevance. For PH domains from dynamin and from Dbl family proteins, this weak binding does appear to be functionally important, although its precise mechanistic role is unclear. In many other cases, it is quite likely that alternative binding partners are more relevant, and that the observed PH domain homology represents conservation of structural fold rather than function.

Background

Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domains were first pointed out as regions of approximately 120 amino acids that share sequence similarity with two such regions in pleckstrin [1,2], a major substrate of protein kinase C in platelets [3]. Following determination of NMR structures of PH domains from pleckstrin [4] and β-spectrin [5], and the efforts of many laboratories to identify protein targets for these small domains, Harlan et al. reported [6] that the N-terminal PH domain from pleckstrin can bind to the phosphoinositide PtdIns(4,5)P2. Detailed analysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding by the PH domain from the amino terminus of phospholipase C-δ1 (PLC-δ1) then provided the first demonstration of specific phosphoinositide recognition by a PH domain [7,8]. Subsequent X-ray crystallographic studies showed that the PLC-δ1 PH domain (PLCδ-PH) forms a cooperative set of precise interactions with the three phosphate groups in the PtdIns(4,5)P2 headgroup with clear stereospecificity [9]. The structure of PLCδ-PH bound to the PtdIns(4,5)P2 headgroup provided a conceptual foundation for understanding how PH and other domains recognize specific phosphoinositides in cellular membranes. A key role for such interactions in cell signaling was revealed when certain PH domains were found to be recruited transiently to the plasma membrane following activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathways by a wide array of cell surface agonists [10, 11]. It has since become clear that PH domains in this group specifically recognize PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (and/or PtdIns(3,4)P2), and do so through interactions that are closely related to those first seen for PLCδ-PH/PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding [12-14]. Our understanding of how certain PH domains bind specific phosphoinositides with high affinity has thus become quite sophisticated, both at structural and functional levels [15,16]. A few of the PH domains that bind particular phosphoinositides with high affinity and specificity have become frequently-used tools (when fused to green fluorescent protein [GFP]) for analyzing phosphoinositide distribution in cells [17].

Although we understand the PH domains outlined above rather well, it is important to appreciate that they constitute only a small fraction of the PH domains identified by sequence homology in the human (or other) proteome. PH domains are in fact the 11th most common type of domain in the human proteome, with 288 examples across 247 proteins according to the current SMART database [18]. Of these, perhaps 10% bind phosphoinositides with high affinity and specificity. Interestingly, high-affinity and specific recognition by PH domains has only been reported for PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,4)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Other phosphoinositides (notably PtdIns(3,5)P2 and PtdIns3P) have their own unique recognition domains, as will be discussed later. The function of the remaining 90% or so of human PH domains is not clear. Many bind phosphoinositides with low affinity and specificity [19,20], but the functional importance of this is not clear in most cases [21]. The burgeoning appearance of domains with the PH domain fold in alternate guises, with likely protein- or DNA-binding functions [22-25], also suggests that the function of many (if not most) PH domains may not involve phosphoinositides at all. The β-sandwich structure exhibited by the PH domain fold may simply represent a stable scaffold onto which many different binding functions can be imposed.

In this article, I will consider two main questions from the perspective of our work on PH domains and other phosphoinositide-binding domains in S. cerevisiae. First, I will consider the fact that phosphoinositide binding domains can be so sharply subdivided based on the phospholipids that they recognize. Second, I will consider the implications for PH domains in general from our recent genome-wide survey of the their phosphoinositide-binding properties in yeast.

PH domains bind strongly to phosphoinositides with two adjacent phosphates

Once it was appreciated that some PH domains specifically recognize membrane phosphoinositides, it seemed reasonable to suggest that there would be examples that bind to each of the naturally occurring phosphoinositides. Specific binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2 was identified first [7,8] – although there remain only one or two PH domains with this property [26]. The next group to be identified, including the Grp1 and Btk PH domains [27,28], was those PH domains that bind PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 with high affinity and specificity. The related PH domains from protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt, DAPP1, and the C-terminal PH domain from TAPP1 all bind both PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 [10,13,19,29-31]. The TAPP1 C-terminal PH domain shows a preference for PtdIns(3,4)P2 over PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 [31], but clearly binds both phospholipids [13]. PH domains with apparent specificity for PtdIns3P, PtdIns4P, or PtdIns(3,5)P2 have been reported based on lipid overlay experiments in which binding of GST/PH domain fusion proteins to nitrocellulose filters spotted with phosphoinositides is studied [26,30,32]. In each of these cases, however, other methods have shown the PH domain to bind PtdIns3P, PtdIns4P or PtdIns(3,5)P2 with low affinity. In our own surface plasmon resonance studies, we have never been able to detect significant specific binding of any PH domain to PtdIns3P, PtdIns4P or PtdIns(3,5)P2. The one PH domain for which clear specific PtdIns3P recognition has been reported with approaches other than overlay experiments is actually a previously unrecognized ‘split’ PH domain (from the GLUE domain of Vps36), and structural studies showed that this PH-like domain binds phosphoinositides in a manner quite distinct from that seen in other well known phosphoinositide-PH domain complexes [33].

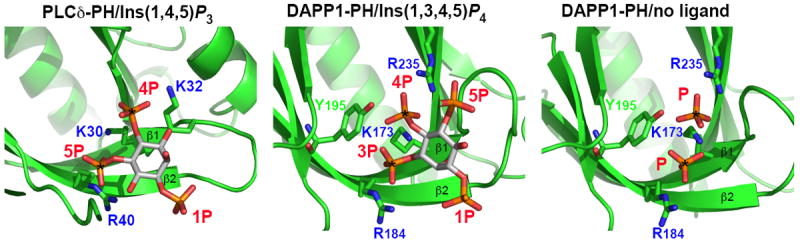

It therefore appears that high affinity and specific PH domains may be restricted to those that recognize PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,4)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Structural studies of PH domain/phosphoinositide interactions provide one appealing possible explanation for this. Common to all of the known structures is an array of basic side-chains that form an extensive hydrogen bonding network with two adjacent/vicinal phosphate groups on the inositol ring [9,12-14], as illustrated in Figure 1 (the two phosphates in each panel marked with asterisks). Indeed, even in the nominally unliganded Grp1 and DAPP1 PH domain crystal structures, these two sites were occupied by sulfate ions [14] or phosphate ions [13]. The two sites are occupied by the adjacent 4- and 5- phosphates of Ins(1,4,5)P3 when it is bound to PLCδ-PH [9] or ARNO-PH [34]. When Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 is bound to the DAPP1 (Figure 1), Btk, Grp1, ARNO, or PKB PH domains [12-14,34,35], almost identical locations are instead occupied by the adjacent 3- and 4-phosphate groups. The inositol ring is effectively flipped 180° between the PLCδ-PH and DAPP1-PH complexes in Figure 1 in order to accommodate this. Thus, the 3-phosphate of Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in the DAPP1-PH complex lies where the 5-phosphate is seen in the PLCδ-PH/Ins(1,4,5)P3 complex, while the location of the 4-phosphate is relatively unchanged (other than being effectively inverted by the 180° flip). It can be argued that this pair of vicinal phosphates (4- and 5, or 3- and 4), seen in all high affinity PH domain/inositol phosphate complexes, make the core set of interactions that drive phosphoinositide recognition by PH domains. Additional binding energy (and specificity) is derived from hydrogen bonds made with phosphate groups outside this vicinal pair (the 1-phosphate in PtdIns(4,5)P2/Ins(1,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2/Ins(1,3,4)P3; the 1- and 5-phosphates in PtdIns(3,4,5)P3/Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 complexes), but the vicinal pair seems to be critical. A sequence motif suggested initially by Skolnik and colleagues [36], and subsequently visualized in structural studies [13,14] has a conserved basic residue at the end of strand β1 (K30 in PLCδ-PH, K173 in DAPP1-PH: see Figure 1) and a second critical basic residue in the middle of strand β2 (R40 in PLCδ-PH, R184 in DAPP1-PH: see Figure 1). Together, these two side-chains appear to define hydrogen bonding interactions with the key pair of vicinal phosphate groups in the target phosphoinositide. The β1 lysine hydrogen bonds with both phosphates, and the β2 arginine hydrogen bonds with the phosphate in the 3/5 position. Our recent genome-wide analysis of PH domains in yeast [26] showed that all PH domains that bind reasonably strongly to phosphoinositides have these two basic amino acids conserved. This aspect of the motif was found in only one or two examples that did not bind strongly to phosphoinositides in our yeast study.

Figure 1. Location of the binding site for two adjacent phosphate groups in the PLC-d1 and DAPP1 PH domains.

Figures were generated using the coordinates of PLCδ-PH bound to Ins(1,4,5)P3 [9] (left panel) and DAPP1-PH [13] bound to Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (middle panel) or with bound phosphates from the crystallization buffer (right panel). Each PH domain is in the same orientation, and the view is centered on the inositol phosphate binding site. Strands β1 and β2 of the PH domain are marked, as are the phosphate groups and the key basic side-chains involved in hydrogen bonding to the phosphates. The two vicinal phosphates that appear to be in a common location in these and all other high-affinity PH domains [34] are marked with asterisks. Note that the orientations of Ins(1,4,5)P3 in the left panel and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in the middle panel are related by a 180° rotation about an axis close to a line that can be drawn between the 1- and 4-phosphates. K30/R40 in PLCδ-PH and K173/R184 in DAPP1-PH are the key basic residues in the β1/β2 loop motif first identified by Skolnik and colleagues [36].

Thus, an important characteristic of phosphoinositides that are specifically (and tightly) bound by PH domains is that their headgroup contains a pair of vicinal phosphate groups. Structural studies to date indicate that PH domain/phosphoinositide interactions are driven largely (if not exclusively) by interactions with the inositol phosphate headgroup. PLCδ-PH, for example, binds ~10-fold more strongly to free Ins(1,4,5)P3 than to PtdIns(4,5)P2 in membranes [7], and Grp1-PH binds ~20-fold more strongly to Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 than to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in a neutral lipid background [19,37]. As described in the next section, the dominance of headgroup interactions and reliance on a pair of adjacent phosphates is unique to PH domains.

Phosphoinositides without two adjacent phosphates are recognized by other types of domain

In the absence of PH domains that bind specifically and strongly to PtdIns3P, PtdIns4P, PtdIns5P or PtdIns(3,5)P2 – i.e. phosphoinositides that do not have two adjacent phosphates in their headgroup – one might expect that other classes of domain exist to fulfill this function. Indeed FYVE domains and PX domains have been known for some time to bind specifically to PtdIns3P [15,16,38,39]. All known FYVE domains select this phosphoinositide. For PX domains, our own studies have indicated that all yeast examples are PtdIns3P-specific [40], but a few cases have been reported in mammals of PX domains that may bind PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 or PtdIns(4,5)P2 [41-43]. Structural studies of FYVE and PX domains have provided reasonably clear views of how they recognize PtdIns3P. Their interactions with PtdIns3P-containing membranes are clearly less reliant on headgroup binding alone than is the case with PH domains. Although the pattern of phosphate groups in the PtdIns3P headgroup is important in defining specificity, interactions with other parts of the lipid and/or membrane are required for high-affinity membrane association.

FYVE Domains

In the case of zinc finger-like FYVE domains [44], side-chains from a basic motif in the first β-strand [(R/K)(R/K)HHCR] account for nearly all hydrogen bonds seen between the PtdIns(3)P headgroup and the FYVE domain [45]. Hydrogen bonds are made with the 1- and 3-phosphates of the PtdIns3P headgroup, but also with the 4-, 5-, and 6-hydroxyls of the inositol chair (which would be disrupted if these positions were phosphorylated) – thus defining the PtdIns3P-specificity of the FYVE domain. Despite this specificity, FYVE domains bind the isolated PtdIns3P headgroup (Ins(1,3)P2) with rather low affinity (KD >20μM [45]). By contrast with PH domains, FYVE domains bind much more strongly to their target lipid in membranes than to the isolated inositol phosphate headgroup [46]. This appears to result in part from the insertion of nonpolar side-chains from a ‘membrane interaction loop’ of the FYVE domain into the membrane interior [44,47,48]. In addition, coiled coil-mediated FYVE domain dimerization has been shown to be important for high-avidity PtdIns3P recognition by some FYVE domains within the cell [45,49,50].

PX Domains

PX domains, like FYVE domains, also make relatively few direct hydrogen bonds with the inositol phosphate headgroup of PtdIns3P [51], suggesting that their affinity for Ins(1,3)P2 is quite low. Specificity appears to be defined by the pattern of hydrogen bonds with the 1- and 3-phosphates as well as 4- and 5-hydroxyl groups of the PtdIns3P headgroup. A crystal structure of the p40phox PX domain bound to dibutanoyl-PtdIns3P [51] indicated that direct van der Waals interactions are also made between the PX domain and the glycerol backbone of the phospholipid, involving a ‘membrane interaction loop’ that NMR and monolayer studies further suggest to penetrate the lipid bilayer to enhance binding to PtdIns3P in membranes [52,53]. Thus, PX domains again invoke additional membrane-interaction mechanisms to enhance affinity.

PtdIns(3,5)P2 Recognition

It is currently less clear how PtdIns(3,5)P2 is specifically recognized. The ESCRT complex component Vps24p has been reported to bind PtdIns(3,5)P2 specifically [54], as have the ENTH domains of Ent3p and Ent5p in S. cerevisiae [55,56]. However, we have been unable to detect high-affinity binding of these proteins (or their constituent domains) to PtdIns(3,5)P2 using a variety of approaches [57,58]. On the other hand, the PROPPINS [57], exemplified by Svp1p/Atg18p from S. cerevisiae [59], represent a novel group of β-propeller proteins that do bind PtdIns(3,5)P2 with high affinity and specificity. A basic motif with the consensus sequence E/Q-ψ-R-R-G in the β-propeller of Svp1p/Atg18p, which is conserved in other PROPPINs, is critical for PtdIns(3,5)P2 binding [59] and suggests that the β-propeller itself constitutes the phosphoinositide-binding site. Other members of the family may be more promiscuous in their phosphoinositide recognition, binding both PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 [60,61], but the PROPPINs certainly appear to represent a novel class of phosphoinositide-recognition protein that is distinct from PH domains in not requiring a pair of vicinal phosphates. A thorough understanding of how PROPPINs recognize PtdIns(3,5)P2 and PtdIns3P awaits determination of their structures, as well as analysis of the extent to which they may penetrate the membrane surface.

PHD Fingers

The one remaining phosphoinositide that we have not discussed is PtdIns5P – again lacking pairs of vicinal phosphates in the headgroup. PtdIns5P has been reported to bind specifically to the PHD (for plant homeodomain) zinc fingers of the nuclear candidate tumor suppressor ING2 [62] and a plant trithorax homolog [63]. These proteins are thought to function as nuclear receptors for this phosphoinositide.

Thus, while phosphoinositides that have a pair of vicinal phosphates appear to be targeted by PH domains that bind to them primarily through interactions with the inositol phosphate headgroup, other phosphoinositides are recognized by quite different groups of domains that utilize a combination of membrane-targeting mechanisms for their association with bilayers containing PtdIns3P or PtdIns(3,5)P2, for example. Whereas FYVE, PX, and other domains have all been observed to penetrate their target membranes, it is generally viewed that PH domains do not require such interactions to drive specific phosphoinositide-driven membrane association [64]. It should be noted, however, that several studies do suggest that the PLC-δ1 PH domain is membrane active [65-67] – although the details and thermodynamic consequences are not yet clear.

Unique puzzles presented by the OSBP/FAPP1/Osh1p group of PH domains

One group of PH domains presents interesting puzzles with regard to both their phosphoinositide-binding characteristics and their subcellular localization. Given what I have outlined above, in vitro phosphoinositide binding by these PH domains is difficult to explain, since they appear to bind similarly to all phosphoinositides tested – regardless of the presence of two vicinal phosphates. Moreover, when their subcellular localization is analyzed, some of these PH domains are found to be associated specifically with the Golgi [26,68,69], despite the fact that other PH domains with identical phosphoinositide-binding specificities are instead plasma membrane-targeted. These findings suggest the existence of additional non-phosphoinositide targets.

in vitro Phosphoinositide Binding by OSBP/FAPP1/Osh Family PH Domains

The PH domains from oxysterol binding protein (OSBP), Goodpasture antigen binding protein (GPBP), FAPP1, and the S. cerevisiae OSBP homologs Osh1p and Osh2p all bind in vitro with reasonable affinity (KD values in the ~1 to ~20μM range) to PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns4P and other phosphoinositides [26,68]. Although FAPP1’s PH domain was identified in lipid overlay studies as a PtdIns4P-specific PH domain [30], this specificity is not apparent with other approaches [68] (Keleti and Lemmon, unpublished). Nonetheless, the fact that this group of PH domains binds with similar affinity to PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2, for example, sets them apart from other PH domains, since PtdIns4P does not possess a pair of vicinal phosphate groups. In our studies of the Osh2p PH domain, KD values for binding to vesicles containing PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,5)P2, PtdIns3P and PtdIns4P fell within the narrow range of 1-1.5μM [26], arguing that the presence of 3 rather than 2 phosphates does not significantly increase binding affinity, and nor does the occurrence of two vicinal phosphates. These PH domains all contain the basic motif in their β1/β2 loop region that was mentioned previously. It is possible that the basic side-chains in the β1/β2 loop motif of these PH domains are arranged differently in space, such that they select two phosphate groups in an inositol headgroup that are separated by an unsubstituted hydroxyl. Without other restrictions on the orientation of the headgroup, this would allow PtdIns3P, PtdIns4P, PtdIns(3,5)P2, and PtdIns(4,5)P2 to bind with similar affinities – although one might expect relatively low affinities for such an unconstrained binding site. To test this hypothesis, structural studies of one or more of these PH domains is required, bound to a series of different headgroups. An alternative possibility is that this group of PH domains achieves high-affinity binding to phosphoinositide-containing vesicles by inserting unidentified hydrophobic regions of the domain into the membrane – similar to the insertion of the ‘membrane interaction loop’ employed by FYVE and PX domains. Under these circumstances, binding to the inositol phosphate headgroup of phosphoinositides by the OSBP/GPBP/FAPP1/Osh PH domains might have very low affinity and specificity – with the binding energy lost compared with other PH domains replaced by membrane penetration.

Targeting of OSBP/FAPP1/Osh Family PH Domains to the Golgi

Levine and Munro [70,71] first noted that the PH domains from OSBP and its S. cerevisiae homolog Osh1p are selectively recruited to the Golgi. In subsequent studies, they found that the OSBP, FAPP1, and GPBP PH domains are all specifically targeted to the Golgi in a manner that depends on the production of PtdIns4P at the Golgi by the phosphoinositide 4-kinase Pik1p [68]. In our own analysis of S. cerevisiae PH domains [26], we found that the Osh1p PH domains was clearly Golgi-localized when analyzed as a GFP fusion proteins, whereas other PH domains with identical in vitro phosphoinositide-binding characteristics (notably the Skm1p PH domain) were associated with the plasma membrane. Levine and Munro determined that Golgi localization of the OSBP PH domain in yeast is sensitive both to reductions in PtdIns4P production in the Golgi and to mutations in the ARF1 small GTPase [68]. Interactions with mammalian ARF1 have also been reported for the OSBP and FAPP1 PH domains [72]. Thus, it appears that these PH domains may have dual targets: one phosphoinositide, one protein – a small G protein in this case. PH domains from this class may be targeted specifically to the Golgi because it is the only cellular location at which the phospholipid and protein targets of the PH domain co-exist. Thus, the PH domains from OSBP, FAPP1, Osh1p, etc may effectively be coincidence detectors.

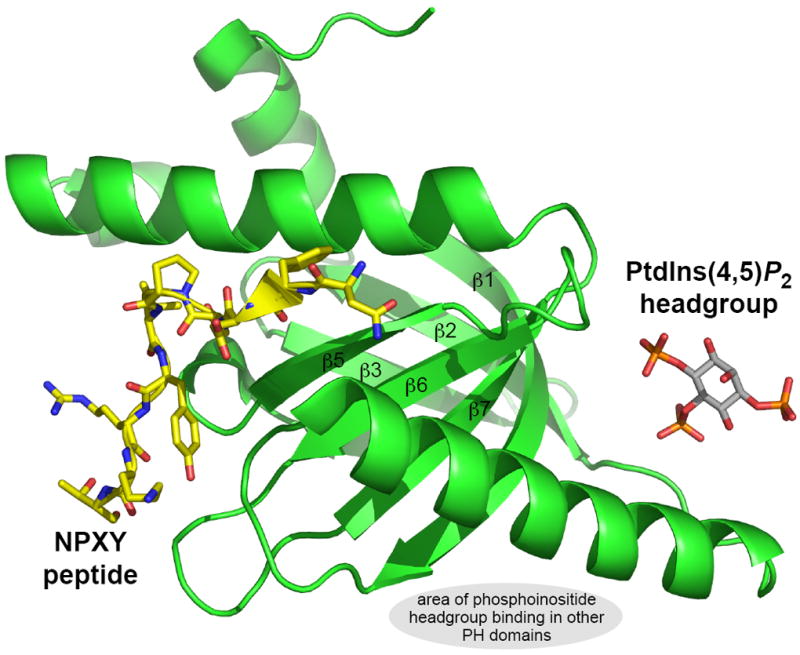

The fact that many proteins and modules that display the PH domain fold are involved in protein/protein rather than protein/phospholipid interactions [21,73] lends credence to this argument. Indeed, there are now several examples of PH domains and PTB domains in which simultaneous binding of a protein ligand and a phosphoinositide to the same PH domain [74] or (PH-like) PTB domain [75,76] has been directly visualized. An example is shown in Figure 2, where an NPXY-containing peptide and the PtdIns(4,5)P2 headgroup were observed bound to the same PTB domain (from disabled-1 [75]). It is possible that protein/lipid coincidence detection of this sort is a property of many PH domains and of otherwise characterized domains that possess the remarkably common PH domain fold.

Figure 2. The disabled-1 (dab1) PTB domain bound simultaneously to PtdIns(4,5)P2 headgroup and an NPXY-containing peptide.

Coordinates were from the structure determined by Stolt et al. [75]. This complex represents an example of how proteins and phosphoinositides may cooperate in driving membrane association of a PTB domain, and indeed PH domains such as those from the OSBP family. The gray oval marks the broad area in which phosphoinositides bind to the other PH domains discussed here.

What do other PH domains do ?

It is clear that some PH domains recognize phosphoinositides with high affinity and specificity. The additional examples outlined above may recognize both phosphoinositides and another – possibly protein – target. In S. cerevisiae, we found that only one of the 33 PH domains identified by the SMART database [18] binds both strongly and specifically to a particular phosphoinositide [26]. This is the Num1p PH domain, which binds to PtdIns(4,5)P2, and shares localization properties in yeast and mammalian cells with the PLC-δ1 PH domain. Thus, the property for which PH domains first became known is actually a rare property for the domain class, only relevant for 3% of yeast PH domains. Our yeast studies showed that only six additional PH domains (from Boi1p, Boi2p, Cla4p, Osh1p, Osh2p, and Skm1p) possess reasonably strong phosphoinositide binding in vitro. All of these PH domains were clearly membrane targeted (to the plasma membrane or Golgi) when analyzed as a GFP fusion protein except for the Boi1p and Boi2p PH domains (although the Boi2p PH domain was membrane targeted according to a Ras recruitment assay [36]). Three other PH domains (from Yil105cp/Slm1p, Ynl047wp/Slm2p, and Opy1p) also showed plasma membrane targeting in our yeast study. Membrane association of the Slm1p and Slm2p PH domains was dependent on PtdIns(4,5)P2 production, and Audhya et al.[77] have since determined that Slm1p and Slm2p form a tight complex and function downstream of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and the TORC2 kinase complex to control organization of the actin cytoskeleton. On the other hand plasma membrane localization of the Opy1p C-terminal PH domain appeared to be phosphoinositide-independent based on our studies of yeast mutants [26], and it remains unclear what drives it to the plasma membrane.

The remaining 23 yeast PH domains showed no evidence of membrane association when analyzed as GFP fusion proteins (although the Ask10p, Caf120p, and Ybl060wp PH domains did show evidence for membrane association in the more sensitive Ras rescue assay). Yet, the majority of these PH domains (some 14 PH domains that showed no evidence for membrane association in any assay) appeared to bind very weakly to phosphoinositides according to lipid overlay assays [26]. This experience has been repeated with many mammalian PH domains, and indeed with many putative phosphoinositide proteins in general [58]. The question that arises is whether the low affinity, occasionally specific, phosphoinositide binding observed in these studies is functionally important – or whether it is simply an artifact (indeed, many proteins will bind highly charged species nonspecifically, and this property is exploited for cation exchange chromatography, for example).

A series of recent studies argue that weak phosphoinositide binding by the PH domains that follow Dbl homology (DH) domains is important for regulating the Dbl family of Rho-guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) [78,79]. In these cases, the GEF is targeted to the membrane (where the Rho GTPase is located) by domains other than the PH domain. Once membrane-targeted, the Dbl protein will experience rather high local concentrations of phosphoinositides, and it is thought that in this context the low affinity PH domain/phosphoinositide interaction is sufficient to promote conformational changes that may allosterically activate the GEF [32,79]. The large GTPase dynamin represents another example in which very low affinity phosphoinositide binding has functional importance. The isolated dynamin PH domain binds to the PtdIns(4,5)P2 headgroup with a KD in the millimolar range [28,80], and binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2-containing liposomes can only be detected when the PH domain is dimerized [81]. Yet, three separate groups, with three independent mutations [82-84], found that impairing the already weak binding of the PH domain to PtdIns(4,5)P2 significantly impairs dynamin function in receptor-mediated endocytosis. It is not yet understood precisely how such low-affinity phosphoinositide binding contributes to dynamin function. One possibility is that dynamin oligomerization allows the PH domain to drive high-avidity multivalent membrane association of dynamin oligomers [21,81]. Alternatively, this binding might play a more direct role in membrane scission by dynamin. As with all such cases in which low affinity phosphoinositide binding by a PH domain is suspected to be important, detailed studies specific to that protein will need to be completed.

Conclusions

Since their identification in 1993, the broad family of PH domains and structural relatives has burgeoned. A very small proportion of PH domains bind phosphoinositides with high affinity and specificity, and drive their host proteins to particular cellular membranes in a way that can be precisely regulated. With the emergence of FYVE domains and PX domains, PROPPINs, and other examples, PH domains that perform this function now appear to be greatly outnumbered by other domains. However, PH domains remain the primary domain class with specificity and high affinity for phosphoinositides with two vicinal phosphates in their headgroup. A subclass of PH domains with little specificity for phosphoinositides (OSBP-relatives) appears to detect the coincidence of phosphoinositides and another target that may be a small G-protein, and this can define precise subcellular localization. In these cases, binding of the PH domain to its protein target may resemble that seen for well described protein-protein interactions driven by modules such as PTB and EVH domains that share the PH domain fold [21,73]. Perhaps one of the biggest challenges for understanding the general properties of this large class of domains is to determine whether the frequently observed low-affinity and promiscuous phosphoinositide binding has functional importance. In a few cases, there are strong signs that such phosphoinositide binding is critical. However, it remains possible that it is a red herring in many cases, and the role played by weak phosphoinositide binding needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis for this functionally heterogeneous domain family.

Acknowledgments

Work in this area in the author’s laboratory is support by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM056846.

References

- 1.Haslam RJ, Koide HB, Hemmings BA. Nature. 1993;363:309–310. doi: 10.1038/363309b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer BJ, Ren R, Clark KL, Baltimore D. Cell. 1993;73:629–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90244-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyers M, Rachubinski RA, Stewart MI, Varrichio AM, Shorr RGL, Haslam RJ, Harley CB. Nature. 1988;333:470–473. doi: 10.1038/333470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon HS, Hajduk PJ, Petros AM, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Fesik SW. Nature. 1994;369:672–675. doi: 10.1038/369672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macias MJ, Musacchio A, Ponstingl H, Nilges M, Saraste M, Oschkinat H. Nature. 1994;369:675–677. doi: 10.1038/369675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harlan JE, Hajduk PJ, Yoon HS, Fesik SW. Nature. 1994;371:168–170. doi: 10.1038/371168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM, O’Brien R, Sigler PB, Schlessinger J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10472–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia P, Gupta R, Shah S, Morris AJ, Rudge SA, Scarlata S, Petrova V, McLaughlin S, Rebecchi MJ. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16228–16234. doi: 10.1021/bi00049a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson KM, Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Sigler PB. Cell. 1995;83:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC, Toker A. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fruman DA, Rameh LE, Cantley LC. Cell. 1999;97:817–820. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baraldi E, Djinovic Carugo K, Hyvönen M, Lo Surdo P, Riley AM, Potter BVL, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Saraste M. Structure. 1999;7:449–460. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson KM, Kavran JM, Sankaran VG, Fournier E, Isakoff SJ, Skolnik EY, Lemmon MA. Mol Cell. 2000;6:373–384. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lietzke SE, Bose S, Cronin T, Klarlund J, Chawla A, Czech MP, Lambright DG. Mol Cell. 2000;6:385–394. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiNitto JP, Cronin TC, Lambright DG. Sci STKE. 2003;(213):re16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2132003re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemmon MA. Traffic. 2003;4:201–213. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rusten TE, Stenmark H. Nature Methods. 2006;3:251–258. doi: 10.1038/nmeth867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavran JM, Klein DE, Lee A, Falasca M, Isakoff SJ, Skolnik EY, Lemmon MA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30497–30508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi H, Kanematsu T, Misumi Y, Sakane F, Konishi H, Kikkawa U, Watanabe Y, Katan M, Hirata M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1359:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM. Biochem J. 2000;350:1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandemark AP, Blanksma M, Ferris E, Heroux A, Hill CP, Formosa T. Mol Cell. 2006;22:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furst J, Schedlbauer A, Gandini R, Garavaglia ML, Saino S, Gschwentner M, Sarg B, Lindner H, Jakab M, Ritter M, Bazzini C, Botta G, Meyer G, Kontaxis G, Tilly BC, Konrat R, Paulmichl M. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31276–31282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gervais V, Lamour V, Jawhari A, Frindel F, Wasielewski E, Dubaele S, Egly JM, Thierry JC, Kieffer B, Poterszman A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:616–622. doi: 10.1038/nsmb782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prehoda KE, Lee DJ, Lim WA. Cell. 1999;97:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu JW, Mendrola JM, Audhya A, Singh S, Keleti D, DeWald DB, Murray D, Emr SD, Lemmon MA. Mol Cell. 2004;13:677–688. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klarlund JK, Guilherme A, Holik JJ, Virbasius A, Czech MP. Science. 1997;275:1927–1930. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salim K, Bottomley MJ, Querfurth E, Zvelebil MJ, Gout I, Scaife R, Margolis RL, Gigg R, Smith CIE, Driscoll PC, Waterfield MD, Panayotou G. EMBO J. 1996;15:6241–6250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowler S, Currie RA, Downes CP, Alessi DR. Biochem J. 1999;342:7–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dowler S, Currie RA, Campbell DG, Deak M, Kular G, Downes CP, Alessi DR. Biochem J. 2000;351:19–31. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas CC, Dowler S, Deak M, Alessi DR, van Aalten DM. Biochem J. 2001;358:287–294. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumeister MA, Martinu L, Rossman KL, Sondek J, Lemmon MA, Chou MM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11457–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teo H, Gill DJ, Sun J, Perisic O, Veprintsev DB, Vallis Y, Emr SD, Williams RL. Cell. 2006;125:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronin TC, DiNitto JP, Czech MP, Lambright DG. EMBO J. 2004;23:3711–3720. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas C, Deak M, Alessi D, van Aalten D. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isakoff SJ, Cardozo T, Andreev J, Li Z, Ferguson KM, Abagyan R, Lemmon MA, Aronheim A, Skolnik EY. EMBO J. 1998;17:5374–5387. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corbin JA, Dirkx RA, Falke JJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16161–16173. doi: 10.1021/bi049017a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellson CD, Andrews S, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1099–1105. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.6.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillooly DJ, Simonsen A, Stenmark H. Biochem J. 2001;355:249–258. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu JW, Lemmon MA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44179–44184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanai F, Liu H, Field SJ, Akbary H, Matsuo T, Brown GE, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:675–678. doi: 10.1038/35083070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song X, Xu W, Zhang A, Huang G, Liang X, Virbasius JV, Czech MP, Zhou GW. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8940–8944. doi: 10.1021/bi0155100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JS, Kim JH, Jang IH, Kim HS, Han JM, Kazlauskas A, Yagisawa H, Suh PG, Ryu SH. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4405–4413. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misra S, Hurley JH. Cell. 1999;97:657–666. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumas JJ, Merithew E, Sudharshan E, Rajamani D, Hayes S, Lawe D, Corvera S, Lambright DG. Mol Cell. 2001;8:947–958. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sankaran VG, Klein DE, Sachdeva MM, Lemmon MA. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8581–8587. doi: 10.1021/bi010425d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kutateladze T, Overduin M. Science. 2001;291:1793–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5509.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stahelin RV, Long F, Diraviyam K, Bruzik KS, Murray D, Cho W. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26379–26388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillooly DJ, Morrow IC, Lindsay M, Gould R, Bryant NJ, Gaullier JM, Parton RG, Stenmark H. EMBO J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stenmark H, Aasland R, Toh BH, D’Arrigo A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24048–24054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bravo J, Karathanassis D, Pacold CM, Pacold ME, Ellson CD, Anderson KE, Butler PJ, Lavenir I, Perisic O, Hawkins PT, Stephens L, Williams RL. Mol Cell. 2001;8:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stahelin RV, Burian A, Bruzik KS, Murray D, Cho W. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14469–14479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheever ML, Sato TK, de Beer T, Kutateladze TG, Emr SD, Overduin M. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:613–618. doi: 10.1038/35083000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitley P, Reaves BJ, Hashimoto M, Riley AM, Potter BV, Holman GD. J Biol Chem. 2002 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306864200. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eugster A, Pecheur EI, Michel F, Winsor B, Letourneur F, Friant S. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3031–3041. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friant S, Pecheur EI, Eugster A, Michel F, Lefkir Y, Nourrisson D, Letourneur F. Dev Cell. 2003;5:499–511. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michell RH, Heath VL, Lemmon MA, Dove SK. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Narayan K, Lemmon MA. Methods. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dove SK, Piper RC, McEwen RK, Yu JW, King MC, Hughes DC, Thuring J, Holmes AB, Cooke FT, Michell RH, Parker PJ, Lemmon MA. EMBO J. 2004;23:1922–1933. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stromhaug PE, Reggiori F, Guan J, Wang CW, Klionsky DJ. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3553–3566. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeffries TR, Dove SK, Michell RH, Parker PJ. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2652–2663. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gozani O, Karuman P, Jones DR, Ivanov D, Cha J, Lugovskoy AA, Baird CL, Zhu H, Field SJ, Lessnick SL, Villasenor J, Mehrotra B, Chen J, Rao VR, Brugge JS, Ferguson CG, Payrastre B, Myszka DG, Cantley LC, Wagner G, Divecha N, Prestwich GD, Yuan J. Cell. 2003;114:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alvarez-Venegas R, Sadder M, Hlavacka A, Baluska F, Xia Y, Lu G, Firsov A, Sarath G, Moriyama H, Dubrovsky JG, Avramova Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6049–6054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600944103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho W, Stahelin RV. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:119–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.133337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tuzi S, Uekama N, Okada M, Yamaguchi S, Saito H, Yagisawa H. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28019–28025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varnai P, Lin X, Lee SB, Tuymetova G, Bondeva T, Spat A, Rhee SG, Hajnoczky G, Balla T. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27412–27422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flesch FM, Yu JW, Lemmon MA, Burger KN. Biochem J. 2005;389:435–441. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levine TP, Munro S. Curr Biol. 2002;12:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roy A, Levine TP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44683–44689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levine TP, Munro S. Curr Biol. 1998;8:729–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Levine TP, Munro S. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1633–1644. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Godi A, Di Campli A, Konstantakopoulos A, Di Tullio G, Alessi DR, Kular GS, Daniele T, Marra P, Lucocq JM, De Matteis MA. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:393–404. doi: 10.1038/ncb1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blomberg N, Baraldi E, Nilges M, Saraste M. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:441–445. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lodowski DT, Pitcher JA, Capel WD, Lefkowitz RJ, Tesmer JJ. Science. 2003;300:1256–1262. doi: 10.1126/science.1082348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stolt PC, Jeon H, Song HK, Herz J, Eck MJ, Blacklow SC. Structure. 2003;11:569–579. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yun M, Keshvara L, Park CG, Zhang YM, Dickerson JB, Zheng J, Rock CO, Curran T, Park HW. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36572–36581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Audhya A, Loewith R, Parsons AB, Gao L, Tabuchi M, Zhou H, Boone C, Hall MN, Emr SD. EMBO J. 2004;23:3747–3757. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rossman KL, Sondek J. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:163–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Worthylake DK, Rossman KL, Sondek J. Structure. 2004;12:1078–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zheng J, Cahill SM, Lemmon MA, Fushman D, Schlessinger J, Cowburn D. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:14–21. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klein DE, Lee A, Frank DW, Marks MS, Lemmon MA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27725–27733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Achiriloaie M, Barylko B, Albanesi JP. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1410–1415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee A, Frank DW, Marks MS, Lemmon MA. Curr Biol. 1999;9:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vallis Y, Wigge P, Marks B, Evans PR, McMahon HT. Curr Biol. 1999;9:257–260. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]