Abstract

Dominant theoretical explanations of racial disparities in criminal offending overlook a key risk factor associated with race: interpersonal racial discrimination. Building on recent studies that analyze race and crime at the micro-level, we specify a social psychological model linking personal experiences with racial discrimination to an increased risk of offending. We add to this model a consideration of an adaptive facet of African American culture: ethnic-racial socialization, and explore whether two forms—cultural socialization and preparation for bias—provide resilience to the criminogenic effects of interpersonal racial discrimination. Using panel data from several hundred African American male youth from the Family and Community Health Study, we find that racial discrimination is positively associated with increased crime in large part by augmenting depression, hostile views of relationships, and disengagement from conventional norms. Results also indicate that preparation for bias significantly reduces the effects of discrimination on crime, primarily by reducing the effects of these social psychological mediators on offending. Cultural socialization has a less influential but beneficial effect. Finally, we show that the more general parenting context within which preparation for bias takes place influences its protective effects.

Keywords: crime, ethnic-racial socialization, parenting, race, racial discrimination

“Being black in U.S. society means always having to be prepared for antiblack actions by whites—in most places and at many times of the day, week, month, or year. Being black means living with various types of racial discrimination from cradle to grave.” (Feagin 2010:187)

Racial discrimination persists and profoundly affects the life chances and routine situations of everyday life for racial minorities in the United States (Essed 1991; Feagin 1991). Despite the persistence of racism, the influence of racial discrimination on social behaviors remains extremely underdeveloped (Brown 2008). Criminal behavior is no exception. Although scholars have long been interested in explaining racial disparities in street crime—the idea that racial discrimination might be implicated in offending was presented as early as 1899 by Du Bois (“In the case of the Negro there were special causes for the prevalence of crime … he was the object of stinging oppression and ridicule, and paths of advancement open to many were closed to him.” [p. 241])—until very recently the idea that personal experiences with racial discrimination are directly implicated in the etiology of offending has been largely unexplored. This neglect is all the more remarkable given the evidence that African Americans, particularly males, engage in more street crime than do whites (Hawkins et al. 2000).1

Early sociological explanations of African Americans’ higher rate of offending centered not on the structural constraints imposed by racial stratification, but on the existence of ostensibly unique aspects of minority culture that subvert conventional behavior and encourage crime and violence (e.g., Miller 1958; Wolfgang and Ferracuti 1967). More recent structural perspectives explicitly incorporate racialized structural constraints, even institutional discrimination, and, yet, the proximal mechanism explaining offending among African Americans in these accounts remains deviant or dysfunctional cultural adaptations (Anderson 1999; Massey and Denton 1993; Oliver 1994; Sampson and Wilson 1995).

The (re)ascendance of strain theory in criminology and critical race theory in sociology has spawned a new approach that emphasizes the salience of racial inequality in micro-interactions. Recent studies, which focus on African Americans, point to interpersonal racial discrimination as an important risk factor for offending (e.g., McCord and Ensminger 2003; Simons et al. 2003; Unnever et al. 2009). This micro-level approach complements existing macro-level explanations of racial disparities in crime by identifying a race-specific interactional risk factor, thereby shedding light on within-place and within-race differences in offending. After all, there is significant variation in individual offending even in the most highly disadvantaged, segregated communities.

In the present study, we seek to build on this nascent literature in two ways. After replicating the finding that interpersonal racial discrimination increases offending among African American males—a group long subject to pernicious discriminatory treatment and viewed as “symbolic assailants” (Skolnick 1966)—we turn our attention to explicating how and why personal experiences with racial discrimination might influence offending. Although contributing to knowledge in important ways, past studies have been limited by one or more of the following: using a single-item measure of discrimination (e.g., Unnever et al. 2009); omitting intervening mechanisms (e.g., McCord and Ensminger 2003); or examining subsets of offending (e.g., aggression; Simons et al. 2006) or behavioral problem scales that combine measures of illegal and problematic behavior (e.g., lying to parents or teachers, staying out past curfew; Simons et al. 2003). The first goal of our study is to develop a theoretical model linking interpersonal racial discrimination to an increased risk of law violation. In doing so, we identify three social psychological mechanisms—emotional distress, relational frames, and beliefs about the legitimacy of conventional norms—to develop an explanatory process model.

The study’s second goal involves a consideration of African American culture but takes a decidedly different approach to culture than that mentioned above. We consider one way that African American culture shapes resilience to racial discrimination through ethnic-racial socialization—a class of adaptive and protective practices utilized by racial/ethnic minority families to promote functioning in a society stratified by race and ethnicity (Hughes 2003). In recent years, research has shown that these socialization practices are important to understanding African Americans’ resilience to racial discrimination (e.g., Fischer and Shaw 1999; Neblett et al. 2008). To date, research has not explored whether ethnic-racial socialization provides resilience to the criminogenic effects of racial discrimination; addressing this lacuna is a primary contribution of the present study. Drawing on extant work, we develop arguments to suggest that ethnic-racial socialization practices provide African American youth with competencies to facilitate noncriminal coping responses to racial discrimination. We argue that differences in the type and amount of ethnic-racial socialization help explain why most African Americans do not respond to racial discrimination with offending.2

In summary, the present study attempts to overcome gaps in our understanding of the race-crime linkage by taking a micro-level approach that integrates theory and research from sociology, criminology, and African American studies as well as insights from critical race theory to specify a model of racial discrimination, ethnic-racial socialization, and crime among African American youth. In doing so, we highlight race-specific risk and resilience factors and emphasize a fundamental tenet of critical race theory: “Racial stratification is ordinary, ubiquitous, and reproduced in mundane and extraordinary customs and experience, and critically impacts the quality of lifestyles and life chances of racial groups” (Brown 2003:294).

In the following pages, we discuss the theory and research undergirding our proposed model and test our hypotheses using several waves of data from a sample of roughly 300 African American male adolescents from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), a survey of black families from Iowa and Georgia. The FACHS is unique; it is the largest in-depth panel study of African Americans in the United States. It overcomes several limitations of previous studies, which tended to focus on poor African Americans living in disadvantaged segments of large cities and thus overlooked the diversity of the African American community and provided a limited and sometimes stereotypical view of this population. The FACHS examines black families in a variety of settings and includes respondents from a range of socioeconomic situations from the very poor to the upper middle class. With its developmental focus and wealth of familial information, the FACHS is particularly well-suited for testing the processes under consideration in the present study.3

RACE, DISCRIMINATION, AND CRIME

Racial disparities in street crime have long engaged the interest of sociologists and criminologists. Although differences are magnified by racial biases in the criminal justice system (Tonry 1995), research indicates that relative to whites, African Americans engage in significantly higher rates of street crime (e.g., Hawkins et al. 2000). Early sociological explanations located the source of higher offending among African Americans in autonomous deviant (black) subcultures, which condoned or encouraged crime, especially violence (Curtis 1975; Miller 1958; Wolfgang and Ferracuti 1967). Although dominating race and crime scholarship for a number of years, this “kinds-of-people” approach was shown to be inadequate, in large part, for its neglect of structural influences (Hawkins 1983).

For a number of years after the demise of cultural deficit explanations, the study of race and crime was “mired in an unproductive mix of controversy and silence” (Sampson and Wilson 1995:37). The classic works of Blau and Blau (1982), Sampson (1987), and later Massey and Denton (1993) and Sampson and Wilson (1995), among others, reignited scholarly research on racial disparities and crime, and replaced the cultural emphasis with a nuanced structural approach. Although differing in several important ways, these explanations all examine the study of race and crime from contextual lenses, focusing on variations in crime rates across communities that vary in ethnic-racial composition and levels of inequality. Here, race is “a marker for the constellation of social contexts” in which individuals are embedded (Sampson and Bean 2006:8). These “kinds-of-places” perspectives emphasize racialized structural forces, such as unemployment and housing discrimination, which converge to produce hypersegregated, economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. The social isolation and concentrated disadvantage of these communities impairs social organization, which weakens the control of crime and is conducive to the emergence of a deviant culture either encouraging or tolerating criminal behavior (Anderson 1999; Massey and Denton 1993; Sampson and Wilson 1995).4 High crime rates in areas with high concentrations of African American residents are the result.

Over the past few decades, a wealth of research has tested these structural explanations (for reviews, see Peterson, Krivo, and Browning 2006; Sampson and Bean 2006). This research shows that racial segregation and concentrated disadvantage play important roles in explaining differences in crime rates across racialized space, and ethnographic work has identified and described the existence of cultural codes or cognitive landscapes, ostensibly adaptations to structural disadvantages (Anderson 1999; Oliver 1994). Despite the considerable scholarly attention to the topic, however, we still do not fully understand the link between race and crime (Oliver 2003; Peterson, Krivo, and Hagan 2006). Indeed, after finding “large, unexplained racial differences” in rates of offending, Krivo and Peterson (2000:557) argued that “new thinking and empirical analyses are required to gain a fuller understanding of the sources of this sizeable racial differential.”

We argue that macro-level approaches, which dominate the scholarly discourse on race and crime, are inadequate because they do not account for the way that race influences micro-interactions. A comprehensive explanation of race and crime must go beyond macro-level social facts to address the practice and lived reality of racism. Given their macro-level foci, existing explanations of the race-crime linkage overlook a key micro-level risk factor associated with race: interpersonal racial discrimination—the blatant, subtle, and covert actions, verbal messages, and paraverbal signals that are supported by white racism and malign, mistreat, or otherwise harm members of racial minorities (Essed 1991; Feagin 1991).5 In general, racial discrimination has not played a central role in explanations of black offending, and, when incorporated, has usually been limited to its institutional form. We posit that fertile ground for new thinking about race and crime involves moving a consideration of interpersonal discrimination to the fore, emphasizing the salience of race as a marker for racialized micro-level interactions, a “kinds-of-situations” approach.

Interpersonal Racial Discrimination and Offending

Interpersonal racial discrimination is a common experience for African American adults (e.g., Landrine and Klonoff 1996) and youth alike (e.g., Sellers et al. 2006), and a wealth of research demonstrates the deleterious consequences of racial discrimination on the physical and mental health of African Americans (e.g., Brown et al. 2000; Williams 1997). Building on this work conceptualizing interpersonal racial discrimination as an adverse, stressful experience, at least 11 recent studies examine the link between racial discrimination and individuals’ risk of externalizing problems, including self-reported violence (Caldwell et al. 2004; Simons et al. 2006; Stewart and Simons 2006), conduct problems or behavioral problems6 (Brody et al. 2006; DuBois et al. 2002; Nyborg and Curry 2003; Simons and Burt 2011; Simons et al. 2003), and delinquency (Unnever et al. 2009), as well as official reports of arrest (McCord and Ensminger 1997, 2003). This work indicates that racial discrimination is associated with externalizing problems whether examined cross-sectionally (Simons et al. 2003) or longitudinally (Caldwell et al. 2004), among adults (McCord and Ensminger 2003) and youth (DuBois et al. 2002). A number of different measures of discrimination are used, but all ask respondents to report whether they have experienced one or more negative acts because, from their perspective, they are black. Our attempt to replicate this work using a measure of self-reported commission of illegal acts leads to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Interpersonal discrimination increases individuals’ risks of offending.

Although growing evidence suggests that interpersonal racial discrimination increases the risk of offending, there is much less clarity about the process through which racial discrimination has its effect. Several recent studies point to various social psychological processes (e.g., Simons et al. 2003, 2006), but these findings have not been pulled together into a formal theoretical model, examined simultaneously, whilst predicting law-violating behavior. Building upon this work and drawing on strain and social learning theories, we conceptualize interpersonal racial discrimination as a highly stressful experience—a form of victimization—cumulative in its effect, which increases the risk of crime by producing distress and shaping cognitive frames about the way the world works.

Social Psychological Mechanisms

The harm of racial discrimination has been conceptualized within the stress process framework (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Pearlin 1989) as an acute stressor producing psychological and physiological distress (e.g., Clark et al. 1999). In criminology, general strain theory (Agnew 1992, 2005), a social psychological elaboration of classic strain theory (Merton 1938), applies the stress framework to criminal offending. This theory views crime as a way of coping with distress produced by strain, defined as negative social relations. Distress, or negative emotions, may pressure individuals to (1) attempt to achieve their goals or attain positively valued stimuli through illegitimate channels; (2) attack, escape, or seek revenge on the source of or a substitute for their negative emotions (often a more vulnerable and readily available substitute); and (3) manage or avoid their distress through other behaviors (for a review, see Agnew 2005).

According to general strain theory, then, racial discrimination generates distress, which increases the likelihood of offending. Two studies show that emotional distress partially explains the effects of racial discrimination on conduct problems (Simons et al. 2003) and violence (Simons et al. 2006). Although general strain theory emphasizes the role of anger as a mediator, the theory also proposes that other negative emotions play a mediating role in the strain–offending link. In this study, we examine the mediating role of depression, which can lead to crime in several ways.7 For example, depression increases impatience and irritability and reduces inhibitions and self-regulation (Berkowitz 1989), and it augments self-absorption while decreasing empathy (Simons et al. 2003). In addition, the hopelessness and disinterest in long-term goals concomitant to depressive symptoms reduce individuals’ stakes in conformity (DeCoster and Heimer 2001; Harris, Duncan, and Boisjoly 2002). A previous study using the FACHS data linked discrimination to conduct problems through depressive symptoms (Simons et al. 2003). This leads to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Depression partially mediates the effect of racial discrimination on offending.

Whereas Agnew (1992) highlights negative emotions, earlier strain theorists proposed that beliefs about the legitimacy of social norms and conventions might link discrimination to offending. In particular, Cloward and Ohlin (1960:121) contended that discrimination “justifies withdrawal of attributions of legitimacy from conventional rules of conduct,” including official norms, by eroding individuals’ beliefs that adherence to the rules of the system (defining normative conduct) will lead to fair and equitable rewards.8 Frequent experiences with discrimination may lead youth to perceive the conventional system and its representatives as unjust, thereby “cancel[ing] the individual’s obligation to the established system, and provid[ing] advance justification for his subsequent acts of deviance” (Cloward and Ohlin 1960:188). This expectation is consistent with Tyler’s (1990) model of procedural justice, which posits that people obey the law when they believe it is legitimate, a belief largely based on fair treatment. This idea is also consonant with Anderson’s (1978:130) conclusion from his ethnographic study that many of the “hoodlums” he observed “felt wronged by the system, and thus its rules do not seem to be legitimate.” From these perspectives, attenuated commitment to or disengagement from conventional norms links discrimination to offending. This leads to our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Disengagement from conventional norms partially mediates the effect of discrimination on offending.

Another way that racial discrimination might increase the likelihood of offending is through cognitive frames about relationships and the motives of interactional partners. Individuals have social schemas of relationships and others that vary on a continuum from benign to hostile. Research by Dodge and colleagues (Dodge 2006; Dodge, Bates, and Pettit 1990) indicates that abusive and disrespectful relationships teach individuals that others have hostile intentions and are untrustworthy. Persistent exposure to antagonistic relationships may lead to the development of a hostile view of relationships, whereby individuals impute hostile intentions in situations that are ambiguous or benign. This bias guides an individual’s attention to social cues, perceptions of intent, and situational definitions, and therefore shapes behavioral responses (Dodge 2006). Individuals with hostile views of relationships believe they must use coercive measures to obtain what they deserve and to punish wrongdoers. Such individuals are hypersensitive to threat and consider a strong, proactive response to be necessary (Dodge 1980).

From this perspective, racial discrimination—abusive and antagonistic interactions—impress upon minority youth that the world is a hostile place and thus aggressive and coercive behaviors are justified, making offending more likely. Past research shows that hostile attribution biases are held by violent and aggressive children, institutionalized delinquents (Slaby and Guerra 1988), and antisocial adults (Epps and Kendall 1995). Moreover, two studies find that hostile views explain a portion of racial discrimination’s effect on violent behavior and conduct problems (Simons et al. 2003, 2006). This leads to our next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: A hostile view of relationships partially mediates the effect of racial discrimination on offending.

To sum up our arguments thus far, we argue that interpersonal racial discrimination is an antagonistic, stressful experience, cumulative in its impact on increasing the risk of offending. We posit that racial discrimination produces distress, imparts messages about the unfairness of the social system, and shapes cognitive frames about relationships. We do not claim that this model is exhaustive, and thus we do not expect that the effects of racial discrimination on crime will be fully explained, as other factors may play a role, such as anger and defiance (e.g., Sherman 1993; Unnever and Gabbidon 2011). However, we believe the mechanisms under examination provide a parsimonious theoretical model linking interpersonal discrimination to offending and serve as a solid foundation from which to examine the protective effects of ethnic-racial socialization.

ETHNIC-RACIAL SOCIALIZATION AS A RESILIENCE FACTOR

A primary task for families is preparing their children to function successfully in society. This involves teaching children about the values and rules of society as well as expected future behavior (Clausen 1968). Through this process, known as socialization, individuals acquire an understanding of recognized roles, statuses, and prescribed behaviors and locate themselves and others in the social structure (Thornton et al. 1990). Effective socialization, then, is that which provides children with the necessary skills to function in society.

Given the persistence of white racism and racial stratification, racial minorities’ situations and experiences are distinct from that of white children and require unique competencies. Research shows that one adaptation minority families have made to this oppressive reality is ethnic-racial socialization (hereafter ERS)—a class of protective practices used to promote minority children’s pride and esteem in their racial group and to provide children with competencies to deal with racism (Hughes 2003; Neblett et al. 2008). Peters and Massey (1983:210) summarize results from their classic study as follows: “The knowledge that in America there is a pervasive negative stigma attached to being Black motivates some parents to emphasize Black identity, to teach children to respect, understand, and accept themselves as Black. [Black parents feel] that they have a dual task: to give their children a positive Black identity and to teach children how to cope in a hostile world.” A growing body of research documents the existence and importance of ERS in black families (for excellent reviews, see Hughes et al. 2006; Lesane-Brown 2006).

Although current evidence indicates that a majority of black parents engage in ERS, the content and frequency of these messages vary (e.g., Brown et al. 2007). Scholars have developed specific typologies representing different content messages that parents send to their children.9 Most conceptualizations of ERS encompass parents’ efforts to foster children’s knowledge and appreciation of cultural values (cultural socialization) and to prepare children for experiences with racism (preparation for bias; Hughes et al. 2006).

Cultural Socialization

Cultural socialization is defined as “parental practices that teach children about their racial or ethnic heritage; that promote cultural customs and traditions; and that promote children’s cultural, racial, and ethnic pride, either deliberately or implicitly. Examples include talking about important historical or cultural figures; exposing children to culturally relevant books, artifacts, music, and stories; celebrating cultural holidays,” and the like (Hughes et al. 2006:749). These caregiving strategies have evolved to promote a sense of cultural well-being and pride in minority children in a racist society (Peters 1985).

Learning about African American culture almost certainly occurs naturally in the home through tacit socialization (Boykin and Toms 1985; Brown et al. 2007). Yet, among most black parents, cultural socialization is a conscious activity, and this includes specific ethnic teachings (Hughes et al. 2006). By making culture salient and providing information about ethnic practices and the achievements of group members, caregivers build knowledge of and pride in cultural traditions and values. These practices undergird racial identities in African American youth (e.g., McHale et al. 2006), which are associated with more positive mental health and general psychological well-being (Caldwell et al. 2002; Sellers et al. 2006). Cultural socialization has also been directly linked to more favorable views of African Americans (Demo and Hughes 1990; Stevenson 1995), higher self-esteem (Stevenson et al. 1997), and higher academic achievement (Smith et al. 1999). Additionally, research indicates that cultural socialization is inversely related to externalizing behaviors (e.g., less fighting and better anger management, especially among boys) and internalizing problems (e.g., reduced depression, anxiety, and psychological distress [Bynum, Burton, and Best 2007; Caughy et al. 2002]).

In summary, studies that examine cultural socialization in African American families consistently report that it is associated with adaptive functioning. Based on this work, we expect that cultural socialization has a compensatory effect on racial discrimination.10 Specifically, this leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: Cultural socialization is inversely associated with offending, depression, disengagement from conventional norms, and hostile views of relationships (compensatory effect).

In addition to this compensatory effect, there is reason to believe that cultural socialization may help youths manage the challenges, such as discrimination, that accompany being black in the United States (Peters and Massey 1983). Research on this idea is scarce and mixed (Bynum et al. 2007; Harris-Britt et al. 2007); thus, we will also examine the possibility that cultural socialization moderates effects of discrimination on crime and the proposed intervening mechanisms.

Preparation for Bias

Most African Americans will face discrimination in their lives. Black youth who are not prepared to interpret and cope with racism are ill-prepared for the discrimination they will inevitably encounter in U.S. society (Spencer 1983; Stevenson et al. 1997). Cognizant of this reality, black parents report that a critical component of their parenting is making their children aware of racism and teaching their children how to deal with its various manifestations (Hughes et al. 2006; Lesane-Brown 2006). These various efforts by parents are called preparation for bias.

Preparation for bias reflects, at least in part, the translation of social experiences into proactive child socialization practices, a process that involves caregivers anticipating their children’s exposure to analogous social situations and explicating strategies to enhance their children’s capacity to interpret, respond, and cope with them (Phinney and Chavira 1995). Caregivers attempt to teach children coping behaviors that have proven helpful in the past, including various strategies that help overcome racism (Peters 1985). In addition, bias preparation reflects experiential wisdom passed along through generations (Hughes and Chen 1999).

Fewer studies have examined the effects of preparation for bias than cultural socialization, and the findings are mixed (Hughes et al. 2006). On one hand, preparation for bias has been linked to positive outcomes, including higher self-esteem and fewer depressive symptoms (e.g., Hughes and Chen 1999; Stevenson et al. 1997). On the other hand, bias preparation has been linked to negative outcomes such as lower academic performance, increased felt stigmatization, and increased fighting frequency (e.g., Stevenson et al. 1997).

Rather than exerting a direct effect, theory and research suggest that preparation for bias provides resilience by buffering the effects of racial discrimination. Preparation for bias potentially reduces the deleterious consequences of discrimination both because it warns youths about discrimination, thus making it less likely they are caught off guard, blame themselves, or feel alone in circumstances where they experience discrimination, and because it provides them with skills to cope with racial discrimination. Scholars argue that unexpected discrimination is more stressful (Cooper et al. 2008) and that preparation for bias helps adolescents appropriately attribute race-based unfair treatment to external sources (Crocker et al. 1991). More obviously, youths who have been taught prescriptions for coping with racist discrimination might handle these experiences more effectively (Hughes et al. 2006; Peters 1985; Spencer 1983). In the only study to directly examine ERS and styles of coping with discrimination, Scott (2004) found that among black adolescents, preparation for bias directly increased the use of adaptive coping strategies, such as social-support seeking and problem-solving, and indirectly augmented perceived control over discrimination experiences.

At least two studies have examined the protective or buffering effects of preparation for bias. In the first, Fischer and Shaw (1999) found that preparation for bias (“racism awareness teaching”) attenuated the effect of discrimination on decreased well-being and psychological distress in a sample of African American college students. More recently, Harris-Britt and colleagues (2007) found that preparation for bias buffered the effect of discrimination on lower self-esteem. Building on this work, we expect that preparation for bias buffers the effect of discrimination on crime, such that the link between discrimination and crime is weaker for youth who have received more preparation for bias. This leads to our sixth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: Preparation for bias reduces the effects of discrimination on crime (protective effect).

Based on our above discussion, we expect that bias preparation serves as a buffer in part by mitigating racial discrimination’s influence on the mediating mechanisms.

Hypothesis 6a: Preparation for bias reduces the effects of discrimination on depression, hostile views, and disengagement from conventional norms.

We further expect that preparation for bias will reduce the likelihood that these intervening mechanisms will lead to crime when they do develop through its effects on coping. For example, family members may encourage youths to seek out supportive others to deal with depressive symptoms or suggest ways to respond to discrimination proactively and prosocially. This suggests the following:

Hypothesis 6b: Preparation for bias reduces the effects of depression, hostile views, and disengagement from conventional norms on crime.

Caregivers’ warnings about discrimination appear to be a protective factor rather than a compensatory one. We make no hypotheses about the direct effects of preparation for bias.

SUMMARY AND CAUSAL ORDER CONSIDERATIONS

In the present study, we examine the effects of race on crime at the micro-level, highlighting interpersonal discrimination as a race-specific risk factor for crime and cultural adaptations that provide African Americans with resilience. Specifically, replicating previous work, we predict that experiences with racial discrimination increase individuals’ likelihoods of offending (Hypothesis 1). Focusing on mechanisms, we argue that discrimination foments depression, hostile views of relationships, and disengagement from conventional norms, which in turn increase individuals’ offending (Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4). Noting that racial discrimination does not inevitably lead to criminal behavior, we focus on cultural practices that provide resilience to discrimination. We argue that familial cultural socialization, by strengthening racial identity and a sense of community, is inversely associated with crime, in part by reducing depression, disengagement from norms, and hostile views (Hypothesis 5). Furthermore, we predict that preparation for bias buffers the effect of racial discrimination on crime by inculcating competencies to handle discrimination in more adaptive ways (Hypothesis 6).

We test these hypotheses using data from the first four waves of the FACHS. Importantly, while we incorporate measures from all four waves, we focus on the effects of discrimination on crime concurrently (at Wave 4) using measures of ERS practices averaged across Waves 3 and 4. This modeling decision was necessitated by the availability of measures and grounded in our belief that discrimination has a more substantial effect on crime in the short term than in the long term.11 Although this may raise causal order questions, a recent study using the FACHS data showed that racial discrimination was related to increases in both general and violent delinquency over time, but neither general delinquency nor violence was significantly related to increases in racial discrimination (Martin et al. 2011). Furthermore, studies show that distress is not related to later reports of racial discrimination (e.g., Brown et al. 2000). Preliminary analyses testing the causal sequencing of crime, hostile views, disengagement from conventional norms, ERS, and reports of discrimination experiences suggest that the causal order is from racial discrimination to the intervening mechanisms and provide no support for an alternative perspective of reverse causal ordering (see Parts 1 and 2 of the online supplement [http://asr.sagepub.com/supplemental]). These cross-lagged models reveal that discrimination at Wave 3 is significantly related to increases in delinquency at Wave 4, while Wave 3 delinquency is not significantly associated with Wave 4 discrimination.

METHODS

Sampling

The FACHS is a longitudinal, multisite investigation of health and development among African American families living in Iowa and Georgia at the first interview (Gibbons et al. 2004; Simons et al. 2002).12 The FACHS was designed to analyze the particular risks and resources that disrupt or promote African American family functioning and youth development in various contexts. The sites sampled included rural, suburban, and metropolitan communities. Data were collected in Georgia and Iowa using identical research procedures.

Study families resided in neighborhoods that varied considerably on demographic characteristics, such as racial composition and economic level. Using 1990 Census data, block group areas (BGAs) were identified in Iowa and Georgia in which the percent of African American families was high enough to make recruitment economically practical (10 percent or higher) and in which the percent of families with children living below the poverty line varied considerably.13 Caregivers received $100 and youths received $70 for participation in Waves 1 and 2, and $125 each in Waves 3 and 4.

Sample

A total of 897 African American families (475 in Iowa and 422 in Georgia) participated in the first wave of FACHS. Each family included a 5th-grade target youth at Wave 1. Fifty-four percent were female. Most (84 percent) of the primary caregivers were the target’s biological mother, of whom 37 percent were married at Wave 1. The mean family income across the four waves of data collection was $32,259. In general, the sample was representative of the African American populations of the communities from which participants were recruited (Cutrona et al. 2000).

The families resided in a variety of settings. Based on criteria developed for the 2000 Census (Dalaker 2001), families’ residential settings were characterized as urban (n = 163), suburban (n = 594), or rural (n = 140). The racial composition of neighborhoods varied considerably. At Wave 4, the average percentage of African Americans in BGAs was 37 percent, and ranged from slightly less than 1 percent to 99 percent. One quarter of respondents lived in BGAs with less than 9 percent black residents, and 25 percent lived in BGAs with at least 60 percent black residents.

Of the 897 families who originally participated in the study, 779 (87 percent) remained in the sample at Wave 2, 767 (86 percent) were in Wave 3, and 714 (80 percent) were in Wave 4.14 Data collection was completed for the waves in 1998, 2001, 2004, and 2007. Youths were 10 to 12 years, 12 to 14 years, 15 to 17 years, and 17 to 20 years in Waves 1 through 4, respectively. This dataset allows for the examination of hypotheses with data spanning adolescence, a time when both offending (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1983) and ERS practices peak (Hughes et al. 2006). Because preliminary analyses revealed qualitative gender differences in the processes examined, we limit our focus to males in the sample. The present sample includes the 306 males interviewed at Wave 4. Ten cases (3 percent) had missing data from Wave 2. For these respondents, we used their Wave 1 scores.15

Measures

Delinquency

The primary dependent variable was generated using youth self-reports at Wave 4. This variable measures the number of different delinquent acts (out of 17) respondents committed in the past year, such as shoplifting (21 percent), aggravated assault (11 percent), marijuana use (33 percent), vandalism (10 percent), theft of personal property (17 percent), physical abuse of an animal (4 percent), breaking and entering (5 percent), assault with a weapon (6 percent), and completed or attempted robbery (2 percent).16 Previous research shows that self-reported survey items are reasonably reliable indicators of delinquent behavior and preferable to police reports (e.g., Huizinga and Elliott 1986). Items were culled from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version 4 (DISC-IV; American Psychiatric Association 1994). Although these items vary in seriousness, our model proposes that the effect of discrimination is general across offenses.17 We summed responses to create a variety count of delinquency.18 Considerable variation exists in the youths’ delinquency; 98 respondents (32 percent) reported committing at least four different offenses in the past year. The mean number of acts committed was 2.86 at Wave 4, and scores ranged from 0 (31 percent) to 15 (.3 percent). The Kuder-Richardson coefficient of reliability (KR20; Kuder and Richardson 1937), designed to assess the reliability of dichotomously scored scales, was .86.19 The control for previous delinquency was created by averaging Wave 1, 2, and 3 scores for the same instrument.

Racial discrimination

We measured youth experiences with racial discrimination at Wave 4 with a revised version of the Schedule of Racist Events (SRE; Landrine and Klonoff 1996). The SRE was designed for adult respondents; FACHS researchers revised the items to make them relevant for youth in late childhood through adolescence. Revisions included simplifying the language and replacing items dealing with discrimination in the workplace with items about discriminatory behaviors in the community (see Simons et al. 2003). Items in the revised SRE instrument assessed the frequency during the past year, ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (frequently), with which respondents experienced specific discriminatory behaviors “because of [his] race or ethnicity.”20 Eleven of the original 13 items were utilized in the present study.21 The measure incorporates racially based slurs and insults, physical threats, false accusations from law enforcement officials, and disrespectful treatment from others (α = .90).

Table 1 displays the discrimination items and their prevalence as well as the discrimination variety count (the number of different acts experienced at least once in the past year). The overwhelming majority (86 percent) of the sample reported experiencing racial discrimination in the past year. Within this majority, however, considerable variation exists in both the number of different discrimination experiences and the frequency of their occurrence. Underscoring the influence of racism on the lives of black male youth, 18 percent indicated that at least one of the items occurred on a frequent basis. On average, respondents experienced almost five different types of discrimination in the past year.

Table 1.

Youth Experiences with Discrimination at Wave 4

| Varietya |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination Items | Never (%) | Once or Twice (%) |

A Few Times (%) |

Frequently (%) |

# | % |

| How often has someone said something insulting to you…? |

40 | 37 | 19 | 4 | None | 14 |

| How often has a store-owner, sales clerk…treated you in a disrespectful way…? |

46 | 32 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| How often have the police hassled you…? |

46 | 22 | 18 | 13 | 2 | 9 |

| How often has someone ignored you or excluded you from some activity…? |

65 | 23 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 10 |

| How often has someone suspected you of doing something wrong…? |

38 | 33 | 20 | 9 | 4 | 8 |

| How often has someone yelled a racial slur or racial insult at you…? |

51 | 32 | 13 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| How often has someone threatened to harm you physically…? |

84 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 10 |

| How often have you encountered people who are surprised that you…did something really well? |

39 | 32 | 20 | 9 | 7 | 10 |

| How often have you been treated unfairly…? |

46 | 32 | 18 | 4 | 8 | 5 |

| How often have you encountered people who didn’t expect you to do well…? |

38 | 29 | 23 | 10 | 9 | 6 |

| How often has someone discouraged you from trying to achieve an important goal…? |

59 | 24 | 12 | 5 | 10 | 9 |

| 11 (All) | 4 | |||||

Note: As an introduction to the discrimination instrument, respondents were presented with the following statement: “Racial discrimination occurs when someone is treated in a negative or unfair way just because of their race or ethnic background. I want to ask you some questions about whether you have experienced racial discrimination. For each statement, please tell me if this situation has happened to you never, once or twice, a few times or several times.” Ellipses refer to “because of your race or ethnic background.”

Discrimination variety count, which counts the number of different discrimination items experienced at least once.

Ethnic-racial socialization

The items for the two ERS scales were adapted from instruments used by Hughes and colleagues and have demonstrated high validity and reliability (e.g., Hughes and Chen 1999). Item content for these measures were originally derived from stories and events described by African American parents participating in focus group interviews (Hughes and Dumont 1993). The items assessed the frequency of a range of familial behaviors and communications to children around the issue of race and ethnicity. For each item, the youth indicated the number of times that adults in their family engaged in the specific behavior during the past 12 months. Starting in Wave 3, respondents answered the ERS instrument. Because we expect effects of ERS to be lasting and cumulative, we combined (averaged) the scales from Waves 3 and 4 to create the measures used in the present study.22

Cultural socialization was measured with youth responses to five questions about how often adults in their family engaged in activities or communications that highlighted African American culture and history or promoted black pride. Coefficient alpha for the measure was approximately .85 at both waves, and the stability correlation was .36. Preparation for bias was measured with six questions that assessed messages youths received about prejudice and discrimination. The items covered explicit verbal communications regarding racial barriers as well as inadvertent messages. Coefficient alpha for the scale was above .86 in both waves, and the stability correlation was .27.

Table 2 presents the frequency of racial socialization practices based on Wave 3 reports, and as with discrimination, there is substantial variation in the amount of racial socialization across respondents. The prevalence of preparation for bias across the two waves is tantamount to cultural socialization (98 percent), and both are consonant with extant research on African Americans (e.g., Hughes et al. 2006).23

Table 2.

Frequency of Ethnic-Racial Socialization Practices at Wave 3

| Number of Times Adults in Family Engaged in Behavior in the Past Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (0) (%) |

1 to 2 (%) |

3 to 5 (%) |

5 to 10 (%) |

10+ (4) (%) |

Mean | |

| Cultural Socialization Items | ||||||

| Celebrated cultural holidays | 27 | 40 | 20 | 5 | 8 | 1.26 |

| Talked about important people or events |

15 | 37 | 28 | 12 | 9 | 1.64 |

| Taken places reflecting racial heritage |

33 | 42 | 18 | 4 | 4 | 1.04 |

| Encouraged to read books about heritage |

19 | 33 | 22 | 9 | 17 | 1.72 |

| Encouraged to learn about his- tory or traditions |

14 | 35 | 29 | 10 | 12 | 1.70 |

| Preparation for Bias Items a | ||||||

| People might limit you | 34 | 27 | 20 | 8 | 11 | 1.33 |

| People might treat you badly or unfairly |

28 | 28 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 1.50 |

| Will have to be better than others |

43 | 25 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 1.16 |

| Talked about discrimination or prejudice |

24 | 32 | 20 | 12 | 13 | 1.58 |

| Explained poor treatment on television |

29 | 35 | 17 | 6 | 13 | 1.39 |

| Talked to others about discrim- ination in your presence |

41 | 32 | 18 | 3 | 6 | 1.03 |

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Each preparation for bias item included the statement “because of your race.”

Intervening mechanisms

The three proposed mediators were measured at Wave 4 with self-reported multi-item scales; controls for prior scores were calculated at Wave 2.24 We created each scale by averaging responses across items. Hostile views of relationships was created with 12 items that assessed respondents’ agreement with statements such as, “When people are friendly, they usually want something from you”; “Some people oppose you for no good reason”; and “It is important to let others know that if they do something wrong to you, you will make them pay for it.” The scale measures the extent to which respondents displayed a hostile attribution bias and viewed coercive responses as instrumental (α = .80). The measure of depression consists of symptom counts for 22 items from the major-depression section of the DISC-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994). These questions gauge the extent to which respondents felt sad, irritable, tired, restless, or worthless; slept more than usual or had trouble sleeping; or had difficulty focusing and making decisions (KR20 = .84). Disengagement from conventional norms was measured with responses to seven questions that ascertained how wrong respondents considered the enactment of various deviant and criminal behaviors, such as physical assault, selling marijuana, cheating on a test, and shoplifting. Response categories ranged from 1 (not at all wrong) to 4 (very wrong) and were reverse coded (α = .83).

Control variables

We included two additional variables in the models to capture theoretically relevant characteristics of the youth and their families. ERS takes place in the context of a general relationship between caregivers and children. Therefore, when analyzing the effects of ERS, we controlled for general parenting quality. Drawing on extensive work on parenting, we conceptualized good parenting as authoritative parenting. This constellation of parenting practices emphasizes caregiver demandingness and responsiveness (Baumrind 1966). We measured authoritative parenting with combined youth and caregiver reports on several multi-item scales, including parental warmth, avoidance of harsh discipline, problem solving, inductive reasoning, and positive reinforcement (for more detail, see Burt, Simons, and Simons 2006).

We also controlled for youth age in years at the time of the interview, which is incorporated into the model after standardization. We considered additional controls, including household income; primary caregiver race, age, and sex; presence of a second caregiver in the home; and neighborhood disadvantage and racial composition. None of these variables significantly influenced the processes under consideration and, thus, were not included in the models.25 The means, standard deviations, and correlation matrix for the study variables are presented in Table A1 in the Appendix.

Analytic Strategy

The analysis proceeds in a series of steps. We first tested the effects of discrimination on crime directly and indirectly through the mediators (Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4) using structural equation modeling (SEM) with manifest variables (also known as path analysis). This estimation method has a number of advantages, including modeling of correlated error terms and multiple endogenous variables, but most importantly for our purposes, path analysis allows one to test direct and indirect effects, including the significance of specific paths, in a system of equations (Bollen 1989). We estimated the path analysis in MPlus 5.2 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010) with a continuous equation using maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square statistic that are robust to non-normality.26

In the next step, we assayed the extent to which ERS practices provided resilience to racial discrimination in a series of econometric models. Because the measure of crime represents counts of engagement in acts and is distributed with substantial overdispersion, models predicting crime were estimated using negative binomial regression models (Long 1997). When examining the effect of discrimination on the three mediating variables, we estimated OLS regression models predicting hostile views of relationships, Tobit models (due to the censored nature of the variable and distribution) predicting disengagement from conventional norms, and negative binomial models predicting counts of depression symptoms. Notably, because we are interested in the effects of racial discrimination on changes in crime, depression, hostile views, and disengagement from norms, we estimated the change in the outcome as a result of discrimination by controlling for the Wave 3 score to predict the Wave 4 outcome (the regressor variable method; Allison 1990). Finally, we evaluated the extent to which preparation for bias buffers discrimination (Hypothesis 6) by incorporating product terms (standard protocol delineated by Aiken and West [1991]) into the respective models. The standard errors in these models were adjusted with the Huber-White sandwich estimator using the BGAs as the clustering units and were estimated in Stata 12 (StataCorp 2011).

RESULTS

Effects of Discrimination on Delinquency

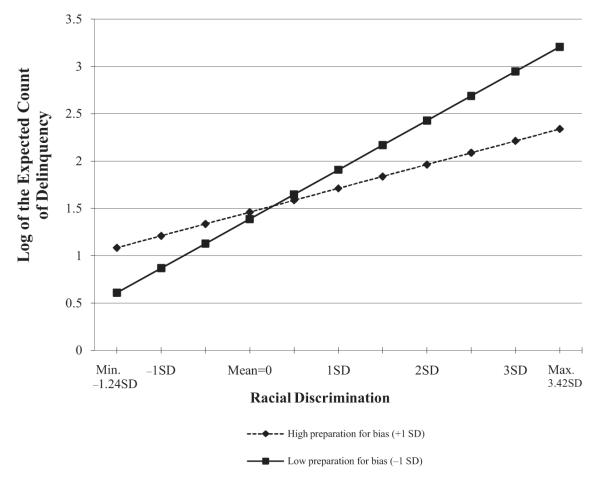

Following the initial estimation of the model, in which we included all potential paths, we constrained insignificant paths (t < 1.5), which were not part of the hypothesized model, and residual correlations to zero to improve model fit. The model fit indices improved with the elimination of the paths and the chi-square difference between the baseline model and the reduced model was not significant (χ2 = 1.237(4), p = .872), supporting the adoption of the reduced model. Figure 1 displays results of the reduced path analyses of racial discrimination on delinquency (standardized coefficients presented). The fit indices for the model indicate good model fit and inspection of the residuals and modifications indices do not indicate any areas of poor fit.27 Overall, the model explains 40 percent of the variation in delinquency.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model of Racial Discrimination on Delinquency

Note: Model fit statistics: χ2(df) = 1.93(5) p = .84; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.03; RMSEA = .00. Standardized estimates are displayed. R2 for the constructs are in parentheses.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Consistent with our hypotheses, Figure 1 shows that racial discrimination exerts a significant and appreciable effect on disengagement from norms, hostile views, and depression. Each of these variables, in turn, has a significant influence on delinquency, net of the effects of prior delinquency and age. Not unexpectedly, racial discrimination continues to have a significant direct (unmediated) effect on offending.

Table 3 displays the decomposition of direct and indirect effects of racial discrimination on delinquency.28 Overall, racial discrimination has a considerable total effect on crime (βs = .36), supporting Hypothesis 1. Consistent with Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4, racial discrimination significantly increases delinquency indirectly through disengagement from conventional norms, hostile views, and depression. Slightly more than 67 percent of the effects of discrimination are indirect through these three variables, with depression accounting for more than half of this mediation. Collectively, these results provide support for our theoretical model, indicating that racial discrimination increases individual offending, and that it does so in large part by augmenting hostile views of relationships, disengagement from conventional norms, and depression.29

Table 3.

Effects of Racial Discrimination on Delinquency (n = 306)

| Standardized Estimate | |

|---|---|

| Total Effects | .356** |

| Indirect Effects | .239** |

| Specific Paths | |

| Discrimination --> Disengage from Norms --> Delinquency | .053** |

| Discrimination --> Hostile Views of Rels. --> Delinquency | .058* |

| Discrimination --> Depression --> Delinquency | .128** |

Note: Estimates based on SEM in Figure 1. Significance tests based on delta method standard errors.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

ERS As Resilience

Our next question was whether ERS practices provide resilience to the criminogenic effects of discrimination. Table 4 presents results testing these hypotheses. Standardized coefficients are displayed for the OLS and Tobit models predicting hostile views and disengagement from norms. For the negative binomial models predicting crime and depression, the table presents the percent change in the expected count for a standard deviation increase in the predictor (%β), holding all other variables constant (calculated as [100 × (eβ − 1)]). Notably, the models displayed in Table 4 reproduce the findings from the path model of a strong effect of discrimination on delinquency. Illustratively, the expected count of offending for an individual who did not report experiencing racial discrimination is 1.48, rises to 2.49 at the mean of discrimination, and increases to 5.30 at two standard deviations above the mean of racial discrimination.

Table 4.

Models Examining Resilience Effects of Ethnic-Racial Socialization on Delinquency and Intervening Mechanisms

| Delinq. | Hostile View |

Disen- gage. Norms |

Depres- sion |

Delinq. | Hostile View |

Disen- gage. Norms |

Depres- sion |

Delinq. | Delinq. | Delinq. | Delinq. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Outcome VaraiblesW4 | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

Model 7 |

Model 8 |

Model 9 |

Model 10 |

Model 11 |

Model 12 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Independent Variables | %β | β | β | %β | %β | β | β | %β | %β | %β | %β | %β |

| Racial DiscriminationW4. | 53.8*** | .337*** | .205*** | 36.5*** | 53.3*** | .339*** | .206*** | 37.3*** | 29.3*** | 27.3*** | 29.7*** | 29.3*** |

| Control for Prior Outcome | 26.6*** | .167*** | .103* | 23.7*** | 27.2*** | .168*** | .108* | 22.2** | 22.3*** | 20.6*** | 21.1*** | 22.1*** |

| Age | 6.6 | −.112* | −.056 | −2.2 | 6.8 | −.106* | −.046 | −2.1 | 11.4* | 11.4* | 10.9† | 11.9* |

| Cultural SocializationW3+W4. | −2.3 | −.082 | −.153* | 8.3 | −4.4 | −.074 | −.166** | 7.7 | −.6 | 1.7 | 1.3 | .5 |

| Preparation for BiasW3+W4 | −1.5 | .191** | .092 | 7.4 | 4.8 | .185** | .145 | 11.8 | −.6 | −.4 | −4.3 | .6 |

| Authoritative ParentingW3+W4 | −16.3** | −.130* | −.274*** | −12.6* | −15.3** | −.129* | −.274*** | −12.8 | −5.9 | −8.0 | −5.5 | −5.5 |

| Hostile View of Relationships | 21.6*** | 24.4*** | 22.6*** | 23.2*** | ||||||||

| Disengagement from Conventional Norms |

30.4*** | 28.9*** | 30.4*** | 29.8*** | ||||||||

| Depression. | 45.3*** | 43.1*** | 47.7*** | 46.7*** | ||||||||

| Discrimination X Prep. for Bias | −15.1* | .014 | −.116* | −10.1 | −12.1* | |||||||

| Hostile View X Prep. for Bias | −14.8** | |||||||||||

| Disengage. Norms X Prep. for Bias | −14.1** | |||||||||||

| Depression X Prep. for Bias | −12.4* | |||||||||||

| R 2 | .16 | .22 | .19 | .13 | .17 | .22 | .20 | .13 | .35 | .36 | .35 | .35 |

Note: N = 306. Standardized estimates shown. Standard errors corrected for block-group clustering using the Huber-White sandwich estimator. The results for models predicting hostile view are OLS models, for rejection of norms they are left censored Tobit models, and for crime and depression they are based on negative binomial models. For the OLS models, the R2 reported is the adjusted R2 and for the Tobit models and NB models the ML (Cox-Snell) R2. %β indicates the percent change in the expected count of crime for a standard deviation increase in the predictor, net of other variables.

p < .07;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Turning to the effects of ERS practices and focusing first on compensation effects, we predicted that cultural socialization would be inversely associated with offending and the intervening mechanisms (Hypothesis 5). In contrast to our hypothesis, Model 1 of Table 4 reveals that cultural socialization does not compensate for the effects of discrimination. Neither preparation for bias nor cultural socialization has a significant direct effect on delinquency. However, it could be the case that cultural socialization reduces the effect of the criminogenic mediators. Results show, however, that cultural socialization is not related to changes in hostile views (Model 2) or depression (Model 4). Cultural socialization does compensate for the effects of racial discrimination on disengagement from conventional norms (β = −.15; Model 3), net of the significant effect of authoritative parenting (β = −.27). Results in Table 4 thus provide evidence that cultural socialization compensates for some of discrimination’s negative effects, but this does not translate into direct reductions in offending.

Preparation for bias, on the other hand, is not directly associated with disengagement from conventional norms (Model 3) or depression (Model 4). It is significantly associated with hostile views of relationships, but in a direction toward increased hostile views (β = .19, Model 2). This finding, while not expected, is not enigmatic. We will return to this finding shortly.

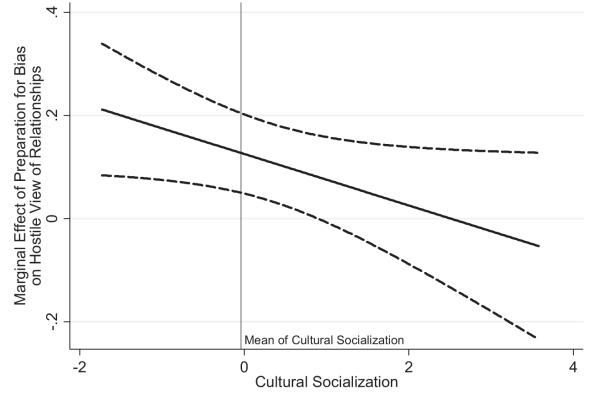

We next turn to the question of whether ERS practices buffer the effects of discrimination. Instructively, we first estimated the protective effects of both preparation for bias and cultural socialization. None of the product terms with cultural socialization were significant or substantively meaningful; we therefore removed them from the models. Model 5 of Table 4 displays results of the model testing whether preparation for bias reduces the effect of discrimination on offending (Hypothesis 6). Results provide evidence in support of the hypothesis; the interaction term is significant and negative (%β = −15.1). To facilitate interpretation of the effect, we graphed the interaction. Figure 2 displays the effects of racial discrimination on delinquency at one standard deviation above and below the mean of preparation for bias and reveals the buffering effects of preparation for bias.

Figure 2.

Effects of Racial Discrimination on the Log Expected Count of Crime at One Standard Deviation Above and Below the Mean of Preparation for Bias (Based on Model 5 of Table 4)

Having found support for our prediction that preparation for bias buffers the effects of discrimination on offending, the final question we sought to answer was how it reduced these effects. Specifically, we considered whether preparation for bias attenuated the effects of discrimination on the intervening mechanisms (Hypothesis 6a) or mitigated their effects on offending (Hypothesis 6b). As Table 4 shows, preparation for bias does not decrease the effects of racial discrimination on hostile views (Model 6) or depression (Model 8). We find partial support for Hypothesis 6a, in that preparation for bias does reduce the effects of discrimination on disengagement from conventional norms in Model 7 (β = −.12), and graphs of this interaction support the buffering hypothesis.30

We then turned to our final hypothesis, that preparation for bias reduces the effects of hostile views, depression, and rejection of norms on crime. Results shown in Models 9 through 11 are consistent with Hypothesis 6b and suggest that the primary way that preparation for bias reduces crime is by buffering the effects of these criminogenic mechanisms on offending. Preparation for bias reduces the effects of all three mediators significantly. Looking at hostile views of relationships in Model 9, for example, we see that the coefficient for the product term is significant and negative (%β = −14.8). We observe the same pattern for the product terms between preparation for bias and disengagement from norms (Model 10) and depression (Model 11). Illustratively, Figure 3 graphs the interaction between preparation for bias and disengagement from conventional norms (Model 10); it is consistent with Hypothesis 6b and conclusions from the point estimates that preparation for bias reduces the effects of disengagement from norms on offending. Returning to Table 4, the interaction term in Model 12 reveals that preparation for bias also attenuates the unmediated effects of racial discrimination on delinquency.

Figure 3.

Effects of Disengagement from Conventional Norms on Crime at One Standard Deviation Above and Below the Mean of Preparation for Bias (Based on Model 10 of Table 4)

In summary, results from Table 4 suggest that ERS practices provide resilience against the criminogenic effects of racial discrimination. Cultural socialization, while beneficial in a variety of other domains (Hughes et al. 2006), appears to play only a small role in this regard, significantly compensating for the effects of racial discrimination on disengagement from conventional norms. Preparation for bias, on the other hand, significantly reduces the effects of discrimination on offending. It does so primarily by decreasing the effects of hostile views, disengagement from norms, and depression on increased offending. The unexpected finding that preparation for bias directly increases hostile views sullies the beneficial buffering effects. To better understand this unexpected finding, we conducted additional analyses.

Supplementary Analyses

Effects of specific parenting practices, including ERS, depend on the general caregiving context (McHale et al. 2006). There is reason to believe that the effects of preparation for bias on increases in hostile views are influenced by other parenting behaviors. We explored two possibilities in this regard. First, we considered the possibility that in the context of a warm, supportive familial environment, preparation for bias might protect youth without producing a general distrusting view of others. At least one study has found that quality parenting moderates the direct effects of preparation for bias on task persistence and school emotional engagement (Smalls 2009). We thus tested the hypothesis that authoritative parenting moderates the effect of preparation for bias on increases in hostile views of relationships, predicting a family context effect.

In addition, we examined the possibility that preparation for bias accompanied by cultural socialization would have less of an effect on increases in hostile views, based on the idea that warnings of discrimination undergirded by caregiver teachings about cultural pride and racial heritage would have less of an influence on negative beliefs about relationships in general. We incorporated product terms between preparation for bias and these two measures in the models to test these predictions. Table 5 displays these results.

Table 5.

OLS Models Examining Moderators of the Effect of Preparation for Bias on Hostile Views of Relationships

| Independent Variables | Model 1 β |

Model 2 β |

|---|---|---|

| Racial DiscriminationW4 | .335*** | .337** |

| Hostile ViewW2 | .156** | .167*** |

| Age | −.104* | −.105* |

| Cultural SocializationW3+W4 | −.075 | −.069 |

| Preparation for BiasW3+W4 | .206*** | .203** |

| Authoritative ParentingW3+W4 | −.130** | −.133** |

| Cultural Socialization X Preparation for Bias | −.105* | |

| Parenting X Preparation for Bias | −.103† | |

| Adjusted R2 | .26 | .26 |

Note: N = 306. Standardized estimates shown. Standard errors corrected for block-group clustering using the Huber-White sandwich estimator.

p < .07;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

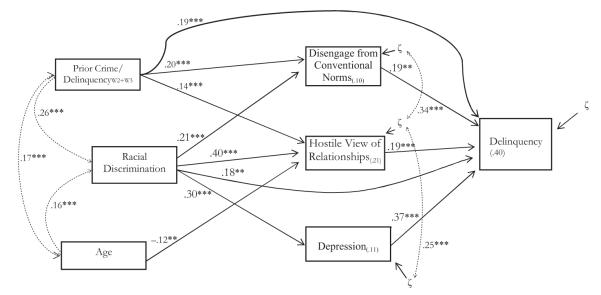

The results in Table 5 support our hypotheses. The interaction between preparation for bias and cultural socialization is negative and significant (Model 1). Figure 4 graphs the marginal effect of preparation for bias on hostile views across levels of cultural socialization and indicates that at high levels of cultural socialization, preparation for bias does not increase hostile views. Turning to authoritative parenting, Model 2 in Table 5 reveals that the interaction between authoritative parenting is negative and marginally significant (p = .06), and graphs of this relationship (not shown) also show that at high levels of authoritative parenting, preparation for bias does not substantially augment hostile views. These results indicate that preparation for bias increases hostile views only in the absence of quality parenting or cultural socialization.

Figure 4.

Marginal Effects of Preparation for Bias on Hostile Views of Relationships across Observed Levels of Cultural Socialization (Based on Model 1 of Table 5)

Note: Dashed lines give 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

“The toxin of racism that runs through the veins of society has yet to find an antidote. Racism can traumatize, hurt, humiliate, enrage, confuse, and ultimately prevent optimal growth and functioning of individuals and communities.” (Harrell 2000:42)

This article argues that interpersonal racial discrimination is an important source of offending among African Americans and thus a contributor to racial disparities in crime. Most contemporary approaches to the study of race and crime have taken a macro-level approach, incorporating institutional racial discrimination as a factor shaping crime rates indirectly through community-level resources, but rarely as a criminogenic risk factor in its own right. Contextual lenses are unable to focus on micro-sociological factors, such as the way race influences interactions. This has created a gap in our understanding of racial disparities in crime, especially how micro-level instantiations of racism influence offending behavior.

Building on several recent studies highlighting the criminogenic nature of interpersonal racial discrimination, the present study takes a micro-sociological approach, relating racial stratification processes to interactional experiences. Arguing that African Americans’ experiences with racial discrimination are recurring, unpredictable, and cumulative in their negative impact, we extended these studies in two ways. First, we specified a theoretical model explaining both why and how personal experiences with racial discrimination increase individuals’ risks of offending. Conceptualizing interpersonal racial discrimination as a stressful, antagonistic, even traumatizing experience, we showed that interpersonal racial discrimination increases offending in large part by increasing hostile views of relationships, disengagement from conventional norms, and depression. These three social psychological mechanisms explained 67 percent of the sizeable relationship between personal experiences with racial discrimination and delinquency.

These results, combined with other research, suggest that experiences with racial discrimination may play a central role in explaining racial disparities in crime and highlight race as a marker for kinds-of-situations (discriminatory interactions). Racial discrimination harms African Americans in a multitude of ways, including by increasing their risk of criminal offending. These findings imply that reducing or eradicating racial discrimination—in addition to being a just goal in its own right—would also be a potent crime reduction strategy.

The second goal of this study was to examine whether a cultural resource among African American families known as ethnic-racial socialization (ERS) provides resilience to the criminogenic effects of interpersonal racial discrimination. A growing number of studies highlight the beneficial effects of ERS, but this is the first study to examine whether it protects against the criminogenic effects of racial discrimination. Our results suggest that it does. In particular, our study highlights the effects of preparation for bias, which protected against the criminogenic effects of discrimination in two ways. First, preparation for bias reduced the effects of racial discrimination on disengagement from norms; second, and more influentially, it attenuated the effect of emotional distress, hostile views, and disengagement from norms on increased offending. Thus, preparation for bias largely operated to reduce negative behavioral responses rather than cognitive or affective ones. These results suggest that preparation for bias protects against racial discrimination primarily by inculcating competencies that allow individuals to cope in noncriminal ways with cognitive-affective factors engendered by discrimination.

Preparation for bias was not a panacea. Indeed, it directly increased hostile views of relationships in the absence of supportive parenting or cultural socialization. There are several potential explanations for this family context effect of preparation for bias on hostile views. For example, mistrust or cynicism resulting from warnings about discrimination may be counterbalanced by caregivers’ prosocial behavior toward their children, which nurtures a benign view of others (Dodge 2006). In addition, by encouraging identification and solidarity with African American culture and heritage, cultural socialization could increase feelings of community and cooperation—sentiments that decrease hostile attribution biases (Dodge 2006). Similarly, celebration of African American achievements and success could impress upon youth that they too can succeed in the face of oppression. Success in important tasks, in turn, has been shown to increase benign views of relationships (Dodge 2006). Alternatively, cultural socialization and authoritative parenting might be capturing unspecified aspects of parenting or parent-child relationships that are consequential for preparation for bias. While further research is needed, our results suggest that preparation for bias is optimally accompanied by cultural socialization and authoritative parenting. When these findings are replicated, future research should further investigate the conditions under which preparation for bias leads to positive outcomes.

The results also suggest that cultural socialization provides some resilience against the criminogenic effects of discrimination. Cultural socialization played a compensatory role by decreasing rejection of conventional norms. That cultural socialization played a less significant role than preparation for bias is not surprising, given that the raison d’être of the latter is to protect against discrimination.

This research adds to the growing number of studies highlighting the role of ERS in promoting resilience. In the past, some social scientific work has denigrated the survival strategies that African Americans developed under conditions of racial oppression and exclusion, using themes of black “cultural deficiency” to blame blacks for their position in society (e.g., Wolfgang and Ferracuti 1967). We adopt a different approach, emphasizing adaptive features of African American culture that provide resilience against criminogenic racial conditions. Importantly, the onus should not be placed on minority groups to deal with discrimination. Certainly, foremost efforts should be focused on extirpating racial discrimination.

Although we believe the results of this study make an important contribution to the body of work on racial discrimination, ERS, and crime, it is not without limitations. First, the sample consists of African American families originally living in various communities in Iowa and Georgia. We assume that processes identified here are not limited to this sample or these contexts, an assumption bolstered by our finding that the prevalence of discrimination and its relationship with depression among the FACHS youth is analogous to that observed among African American adolescents of similar age from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL; Seaton et al. 2008). Moreover, although no nationally representative studies examine the influence of racial discrimination on crime or delinquency, current findings are similar to those found in community samples of adolescents in other areas of the country, including Michigan (Caldwell et al. 2002), North Carolina (DuBois et al. 2002), and California (Unnever et al. 2009). Nonetheless, it is important that future research replicate these findings using different samples. An additional qualification is our focus on males. Future research must attend to females.

Another caveat is related to our measure of racial discrimination. One potential criticism is our use of a perceptual measure of discrimination. We assumed our respondents were relatively accurate in reporting instances of racial discrimination, and a growing body of research attests to the validity of perceptual measures of discrimination and, specifically, the SRE instrument (Landrine and Klonoff 1996). It is important that future researchers continue to explore the validity of and improve upon perceived discrimination measures and assess intergroup and intragroup racial discrimination separately (for suggestions, see Brown 2001, 2008; Clark 2004).

Despite these limitations, this investigation contributes in important ways to our understanding of the race-crime linkage generally and the criminogenic effects of interpersonal racial discrimination, specifically. Future research should take a multilevel approach, as race is simultaneously a marker for both macro-level contexts and micro-level situations. Moreover, contexts shape interactions, such that the racial composition of various life contexts influences the nature of race-related experiences, including racial discrimination and ERS (Sampson and Wilson 1995; Stevenson et al. 2005).

Future research also needs to go beyond measuring whether or not parents transmit various ERS messages and capture specific skill- or identity-building activities or communications so that we can better understand how ERS shapes racism-related coping strategies. Additional research is needed on the impact of other sources of ERS, such as peers and the media, given that adolescents are exposed to many other messages about ethnicity and race from nonfamilial sources.

Overall, findings from the present study reaffirm the functional premise of critical race theory and emphasize the importance of considering the influence of race and racism from a micro-sociological perspective. From a policy standpoint, this research underscores the need to consider and attack racism at multiple levels and emphasizes the crime-reduction potential of a broad antiracist movement. Given that we have not yet found an antidote for racism, this study highlights adaptive cultural practices that can reduce some of the harmful effects of racism on African American youth. Absent a great decline in discriminatory behavior, ERS is one tool that black families are using to reduce discrimination’s effects on offending.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology and the 2011 Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. We would like to thank Tanja Link, Jennifer Lundquist, Christopher Lyons, Andrew Papachristos, Brea Perry, Carter Reese, Eric Stewart, and Don Tomaskovic-Devey for generously providing careful review and valuable comments. We are also grateful for the constructive suggestions from the ASR editors and anonymous reviewers.

Funding This study is based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation, which was supported by a Phelps-Stokes Fellowship at the University of Georgia. This research uses data from the FACHS, a project designed by Ron Simons, Frederick Gibbons, and Carolyn Cutrona, and funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH48165, MH62669), the Center for Disease Control (029136-02), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA021898), and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Biography