Abstract

Objectives

The current study examined associations between PTSD symptoms and future interpersonal victimization among adolescents, after accounting for the impact of early victimization exposure, gender, ethnicity, and household income. In addition, problematic alcohol use was tested as a mediator of the relation between PTSD symptoms and subsequent victimization.

Method

Participants included a national longitudinal sample of adolescents (N = 3,604) who were ages 12 to 17 at the initial assessment; 50% were male; and 67% were white, 16% African American, and 12% Hispanic. Cohort-sequential latent growth curve modeling was used to examine associations among the study variables.

Results

Baseline PTSD symptoms significantly predicted age-related increases in interpersonal victimization, even after accounting for the effects of earlier victimization experiences. In addition, alcohol problems emerged as a partial mediator of this relation, such that one-quarter to one-third of the effect of PTSD symptoms on future victimization was attributable to the impact of PTSD symptoms on alcohol problems (which in turn predicted additional victimization risk). Collectively, the full model accounted for more than half of the variance in age-related increases in interpersonal victimization among youth.

Conclusion

Results indicate that PTSD symptoms serve as a risk factor for subsequent victimization among adolescents, over and above the risk conferred by prior victimization. This increased risk occurred both independently and through the impact of PTSD symptoms on problematic alcohol use. Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that the likelihood of repeated victimization among youth might be reduced through early detection and treatment of these clinical problems.

Keywords: Adolescents, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Alcohol, Victimization

Epidemiological studies estimate that 50-60% of adolescents have experienced interpersonal victimization, including sexual assault, physical assault, and/or witnessed violence, at some point during their lifetime (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2009; Kilpatrick et al., 2000). A strong risk factor for victimization among youth is a history of previous victimization (Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, 2008). For example, in a national sample of children and adolescents, exposure to a broad range of victimization types predicted revictimization within the next year, even after controlling for family demographic variables, stressful life events, and delinquency (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). The long-term adverse impact of victimization during childhood and early adolescence is similar, with re-victimization risk doubling during later adolescence (Humphrey & White, 2000) and remaining significantly elevated through adulthood (Arata, 2000; Desai, Arias, Thompson, & Basile, 2002).

Few studies have examined additional risk factors for adolescent victimization. However, in the adult literature, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms are frequently cited as an outcome of victimization that also predict exposure to additional violence (Cougle, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2009; Elwood et al., 2011; Messman-Moore, Brown, & Koelsch, 2005; Orcutt, Erickson, & Wolfe, 2002). For example, in a longitudinal study of veterans from Operation Desert Storm (1990-1991), PTSD symptoms predicted exposure to subsequent (non-combat-related) traumatic experiences in the two years following the war (Orcutt et al., 2002). A prospective study of college women also found PTSD symptoms to predict later sexual victimization, even after controlling for history of childhood sexual assault (Messman-Moore et al., 2005). Explanations for these findings have focused on the impaired attentional abilities associated with PTSD. Specifically, cognitive research indicates that individuals with PTSD have difficulty disengaging from trauma reminders (Pineles, Shipherd, Mostoufi, Abramovitz, & Yovel, 2009; Pineles, Shipherd, Welch, & Yovel, 2007), which might interfere with their ability to detect novel danger cues in real-life settings and make appropriate decisions about safety (Chu, 1992). Further, the persistent hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD might result in individuals learning to cope with or ignore emotional and physiological fear responses (Barlow, 2002). This can lead to difficulty distinguishing adaptive fear from pathological anxiety and might result in insufficient responses to objectively dangerous situations.

Of note, a few studies conducted with adults have identified differential prediction of victimization based on the three symptom clusters of PTSD (i.e., reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal); however, the results are inconsistent. For example, Cougle et al. (2009) found that the reexperiencing cluster, but not the avoidance or hyperarousal clusters, predicted victimization, whereas another study found that hyperarousal, but not the other clusters, predicted victimization (Risser, Hetzel-Riggin, & Thomsen, 2006).

Given evidence that PTSD symptoms serve as a risk factor of future victimization among adults, it is possible that the same might hold true for adolescents. To our knowledge, however, research has not yet examined these associations in an adolescent sample.1 It cannot be assumed that the findings from the adult literature necessarily apply to adolescents due to developmental differences in victimization experiences. For example, epidemiological studies indicate that, during adolescence, the vast majority of violent assaults (80%) are committed by someone that the victim knows well (e.g., a friend, classmate, or relative; Finkelhor & Ormrod, 2000). In contrast, stranger and acquaintance assaults become much more common as youth enter adulthood (Hashima & Finkelhor, 1999). In addition, victimizations that coincide with the unique cognitive, social, and emotional developmental tasks that characterize adolescence may lead to functional problems in these areas later in life (Cicchetti, 1989; Smith, Davis, & Fricker-Elhai, 2004). In light of this changing context for assaults from adolescence to adulthood, an examination of adolescent-specific victimization risk factors is warranted. The overarching purpose of the current study, therefore, was to test whether PTSD symptoms might increase risk for future victimization among adolescents, above and beyond the risk conferred by previous victimization. Analyses were conducted using a national, random, longitudinal sample of youth who were aged 12-17 at the initial assessment.

Another aim of this study was to provide a test of alcohol problems as a potential mediator of the relation between trauma-related distress and revictimization. Results from the adult literature suggest that PTSD symptoms predict problem drinking, which in turn increases the likelihood of future assault (Ullman, Najdowski, & Filipas, 2009). Much less is known about these relations in adolescent samples. Given that adolescence is the developmental period during which experimentation with alcohol typically begins, problematic alcohol use might serve as a potentially important mediator between PTSD and future revictimization in this age group. Alcohol problems are particularly salient during adolescence, given the emergence and upward developmental trajectory of these problems during this period, as well as the strong association between victimization history and alcohol problems among youth (Champion et al., 2004). Some evidence indicates that victimization in childhood and adolescence is associated with increases in victims’ perceptions of the benefits associated with substance use (Smith et al., 2004). Further, adolescents who experience symptoms of PTSD are at high risk for abusing alcohol (Blumenthal et al., 2008; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2008; Giaconia et al., 2000). Problematic alcohol use can put adolescents at risk for victimization by impairing their ability to detect danger cues (Davis, Stoner, Norris, George, & Masters, 2009), and adolescents who abuse alcohol are likely to associate with peers who engage in delinquent behavior, ultimately increasing their probability of assault (Barnow et al., 2004; Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002). Thus, in addition to examining the impact of PTSD symptoms and early victimization on future victimization in our adolescent sample, the present study investigated the role of problematic alcohol use as a potential mediator of these relations.

The first hypothesis was that PTSD symptoms would increase adolescents’ risk for future victimization, above and beyond the risk conferred by previous victimization. The second hypothesis was that alcohol problems would mediate the relation between PTSD symptoms and future victimization, such that adolescents endorsing more PTSD symptoms would be more likely to display problematic alcohol use, which in turn would predict higher rates of future victimization. Finally, though no predictions could be made about specific relations, we tested the three clusters of PTSD symptoms (reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal) as separate predictors of victimization, as past studies have shown differential albeit inconsistent prediction relations based on cluster. This represents the first longitudinal study of adolescents to examine the extent to which early victimization, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol problems predict age-related increases in these constructs. An additional strength of the study is that analyses are conducted using cohort-sequential latent growth curve modeling (LGM), which is an SEM-based approach that approximates a traditional longitudinal design and has the advantage of explicitly controlling for measurement error and cohort effects, while allowing age-related symptom changes to serve simultaneously as predictors and indicators of other variables (Byrne, 2010).

Method

IRB approval was obtained prior to data collection. The 2005 National Survey of Adolescents-Replication was a nationwide standardized telephone interview of households with adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17, including an oversample of urban households. Sample selection and computer-assisted interviewing were conducted by Schulman, Ronca, and Bucuvalas, Inc. (SRBI), a survey research firm with extensive experience conducting sensitive interviews. A multistage, stratified, area probability, random digit dial six-stage procedure was used to construct the initial probability sample (see Kilpatrick et al., 2000). Once it was determined that a household had at least one youth in the targeted age range, screening and introductory interviews were conducted with parents to establish rapport. Verbal consent from a caregiver or legal guardian was obtained before interviewing the adolescents; all youth gave verbal assent. Strategies were used to ensure adolescent comfort when responding to interview questions. Interviewers ensured adolescents were in a private situation where they could answer freely. In addition, the interviews were designed to include closed-ended questions requiring only “yes,” “no,” or other one-word answers. Thus, if someone in the home were listening, they would be unlikely to hear anything that would violate the adolescent’s privacy. Adolescents were offered $10 to complete the interview. SRBI supervisors conducted random checks of interviewer adherence to assessment procedures.

Given the sensitive nature of some interview questions, several additional steps were taken to increase participant protection. Adolescents who reported during the interview that they (a) had been assaulted by a family member in the past year and (b) had not disclosed the assault to anyone were interviewed by a clinician on the project team to determine if they were in current danger. Those judged to be in danger were encouraged to make a voluntary report to child protective services (CPS). The clinician was prepared to make the report if the adolescent was unwilling to do so. All adolescents also were provided with the number to Child Help, a national telephone counseling program for at-risk youth.

During recruitment, 6,694 households were contacted that resulted in both a completed parent interview and identification of at least one eligible adolescent. Of these, 1,268 (18.9%) parents refused adolescent participation, 188 (2.8%) adolescents refused after their parents consented, 119 (1.8%) adolescent interviews were initiated but not completed, and 1,505 (22.5%) parent interviews were completed but the eligible adolescent was not available at any of our callbacks. The remaining 3,614 cases resulted in completed parent and adolescent interviews. Ten cases were excluded due to age at initial interview, resulting in a wave 1 sample size of 3,604 adolescents ages 12-17. The sample included adolescents from all four U.S. Census regions. Specifically, 34.3% of the adolescents resided in the South, 25.4% resided in the Midwest, 24.2% resided in the West, and 16.1% resided in the Northeast. Participant demographics are similar to national population estimates and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the National Survey of Adolescents-Replication

| Ethnicity |

Wave 1 Annual Household Income |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Cohort |

N | % Girls | % Caucasian |

% African American |

% Hispanic |

% Native Amer./ Alaskan |

% Asian/ Pacific Isl. |

<$20K | $20K to $50K |

> $50K | Not sure/ Refused |

| 12 | 488 | 47.5% | 65.4% | 16.0% | 10.7% | 2.9% | 5.0% | 14.8% | 32.4% | 48.2% | 4.7% |

| 13 | 573 | 48.2% | 65.0% | 17.3% | 11.5% | 3.6% | 2.6% | 13.1% | 31.2% | 48.3% | 7.3% |

| 14 | 631 | 47.4% | 66.9% | 15.9% | 13.1% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 13.5% | 30.1% | 50.1% | 6.3% |

| 15 | 641 | 50.1% | 66.5% | 15.8% | 11.9% | 2.6% | 3.2% | 12.8% | 30.4% | 50.9% | 5.9% |

| 16 | 647 | 52.1% | 66.6% | 16.8% | 11.7% | 1.6% | 3.3% | 10.8% | 27.4% | 53.2% | 8.7% |

| 17 | 624 | 53.7% | 72.0% | 13.7% | 10.7% | 2.1% | 1.5% | 11.7% | 26.3% | 53.7% | 8.3% |

| Total | 3604 | 49.8% | 67.0% | 15.9% | 11.6% | 2.5% | 2.9% | 12.8% | 29.6% | 50.7% | 6.9% |

|

| |||||||||||

| National Estimatesa |

-- | 48.7% | 60.6% | 15.2% | 17.3% | 3.3% | 3.6% | 12.9% | 27.8% | 59.3% | -- |

Note. Demographic variables were assessed using standard questions employed by the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1988). Age was measured as the current age in years at the time of the wave 1 interview (range = 12-17 years). No significant differences in gender, ethnicity, or income were found across cohorts (all chi-square p values > .10). Amer. = American; Isl. = Islander

National estimates reflect U.S. Census estimates of the adolescent population in 2005.

Waves 2 and 3 involved attempts approximately one year apart to re-contact all adolescents included in the original survey. Methods for locating participants who had moved/changed phone numbers included asking about planned moves during the previous year’s interview, acquiring updated contact information from directory assistance, and sending letters to last known addresses. As expected based on the random digit dialing method for participant selection, attrition across study waves was moderately high (33.5% between waves). Attrition was also slightly higher among non-Caucasian relative to Caucasian/non-Hispanic adolescents. Two sets of analyses examined whether attrition was systematically related to the three primary study variables, including interpersonal victimization, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol problems (defined later). First, participants completing versus not completing all three waves were compared. Effect size confidence interval analysis revealed no differences for PTSD symptoms or age (95% CIs include 0.0) and small magnitude differences for interpersonal victimization (Cohen’s d = −.19; 95% CI = −.25 to −.12) and alcohol problems (d = −.08; 95% CI = −.15 to −.01), with study completers endorsing slightly fewer problems at wave 1 relative to non-completers. Second, 200 participants who could not be located at wave 2 were located and re-interviewed during wave 3. Effect size confidence interval analysis revealed no differences between this group and completers for age, interpersonal victimization, or PTSD symptoms for this follow-up (all 95% CIs contained 0.0) and a small magnitude effect for alcohol problems (d = −.18; 95% CI = −.32 to −.03).

Collectively, these analyses suggest that the impact of missing data was minimal. In addition, the cohort-sequential design employed in the current study uses full information maximum likelihood estimation to include all participants and provides estimates based on multiple cohorts, which minimizes the impact of missing data at any individual wave (Byrne, 2010; Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006). Thus, all 3,604 participants contributed data to at least one chronological age group regardless of their pattern of missing data, with a total of 7,500 data points each for the interpersonal victimization, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol problems variables (2,304 participants provided data for at least two waves of data collection and 1,592 adolescents provided data for all three waves).

Measures

Interpersonal victimization

A series of behaviorally specific questions assessed adolescents’ exposure to sexual assault by any perpetrator, physical assault by any perpetrator, or physical abuse from a caregiver. Sexual assault was assessed with seven items that asked whether anyone, including a family or non-family member, had ever forced the adolescent to engage in 1) vaginal sex, 2) anal sex, 3) oral sex on the perpetrator, 4) oral sex from the perpetrator, 5) digital penetration, 6) fondling of the adolescent, or 7) fondling of the perpetrator. Five physical assault items asked whether anyone, including a family or non-family-member, had ever 1) attacked the adolescent with a gun or knife, 2) attacked the adolescent with a stick, club, or bottle, 3) attacked the adolescent without a weapon, 4) threatened the adolescent with a weapon, or 5) attacked the adolescent with fists. Physical abuse from a caregiver was measured with ten items that queried adolescent’s about their experience with different types of caregiver-perpetrated violence, including being 1) thrown against a hard surface, 2) beaten up with fists or kicked, 3) choked, 4) burned on purpose, 5) cut with a sharp object, 6) threatened with a weapon, 7) locked in a closet/tied up, 8) slapped/spanked so hard it caused bruises, 9) slapped/spanked so hard that medical attention was needed, or 9) pushed so hard it caused a fall. For specific wording of questions and details of this methodology, see Kilpatrick et al. (2000, 2003).

At wave 1, the number of victimization events reported in the sexual assault, physical assault, and physical abuse categories were moderately correlated (r range: .26 to .45). For the current study, a summary measure was created at wave 1 reflecting the total number of lifetime victimization events endorsed across all three categories (for a possible range of 0 to 22). At waves 2 and 3, adolescents were asked about events occurring since the last interview. Cumulative lifetime victimization was calculated at waves 2 and 3 by summing the adolescent’s endorsements at that wave with all previous waves. Thus, the wave 2 score reflects the sum of the number of events endorsed at waves 1 and 2, and the wave 3 score reflects the sum of events endorsed at all three waves. In all models, the interpersonal victimization intercept and slope were allowed to covary to control for their expected dependency occurring secondary to the summative method of computing cumulative exposure at waves 2 and 3.

PTSD symptoms

PTSD symptoms were measured using the NSA PTSD module (Kilpatrick et al., 2000). This structured diagnostic interview has 17 questions that assess each of the DSM-IV symptom criteria for PTSD with a yes/no response. Positive endorsements on the NSA PTSD module correspond to moderate-to-severe symptom severity ratings on the PTSD Checklist (PCL; Ruggiero, Rheingold, Resnick, Kilpatrick, & Galea, 2006). None of the PTSD module items is anchored to a specific traumatic event. Therefore, symptoms can relate to a broad range of trauma types (e.g., assault, accident, natural disaster). The PTSD module does not assess criterion A2 for PTSD (i.e., the experience of intense fear, helplessness, or horror during the traumatic event). This criterion was originally developed to ensure that PTSD was not overdiagnosed in light of the broad range of events that meet the DSM-IV definition of trauma (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). However, recent studies have produced mixed evidence for the utility of the A2 criteria. Some studies have found that endorsement of A2 predicts higher levels of PTSD (e.g., Boals & Schuettler, 2009; Hathaway, Boals, & Banks, 2010), whereas a recent large-scale study determined that assessment of the A2 criterion had minimal impact on prevalence estimates of PTSD and, perhaps more importantly, participants reporting A2 did not differ from those not reporting A2 in ratings of severity of dysfunction, including persistence of PTSD symptoms, diagnosis of co-morbid disorders, or suicidal ideation (Karam et al., 2010). Thus, the exclusion of A2 from the current study was expected to have little impact on the relations between PTSD and the other variables of interest. Research on the PTSD module provides support for the instrument’s concurrent validity and several forms of reliability (e.g., temporal stability, internal consistency, diagnostic reliability; Kilpatrick, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1989; Resnick, Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993; Ruggiero et al., 2006).

The wave 1 PTSD module probed for lifetime and past 6-month symptom occurrence, whereas past year and 6-month symptom occurrence were assessed at waves 2 and 3. To maintain a consistent metric across variables and study waves, past year PTSD symptom endorsement at wave 1 was estimated based on past 6-month symptom endorsement at wave 1 by solving regression equations derived from predicting past year PTSD symptoms from 6-month PTSD symptoms at waves 2 and 3 (both R2 = .95).

Alcohol problems

Past year problems due to alcohol use were assessed with questions from the NSA Substance Use module. Research on this module has provided solid evidence of reliability as well as associations in expected directions with relevant constructs, including interpersonal victimization, mental health problems, and familial drug use (Kilpatrick et al., 2000, 2003). Five questions with a yes/no response option assessed negative consequences of alcohol use over the preceding year, including 1) trouble with teachers/fellow students, 2) difficulties with friends, 3) being criticized by a family member, 4) having trouble with police, or 5) having an accident in the home because of drinking alcohol. The total number of past year alcohol problems endorsed was summed and could range from 0 to 5 at each wave.

Data analysis

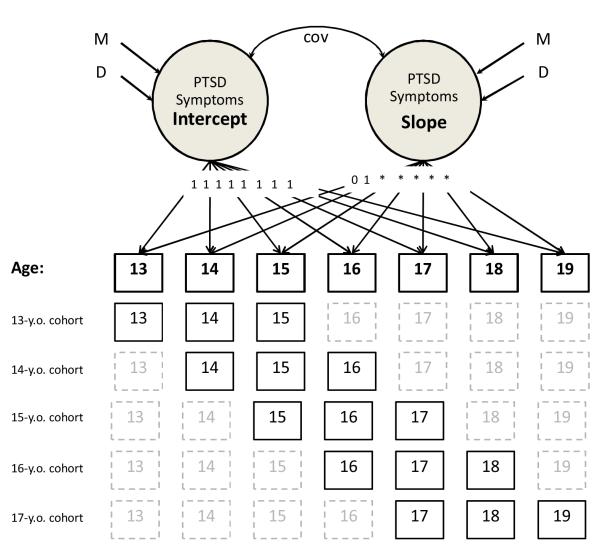

Cohort-sequential LGM was used to examine the interrelations among initial (baseline) levels and age-related changes in PTSD symptoms, alcohol problems, and interpersonal victimization. Individuals were 12 to 17 years of age at the initial interview and were re-interviewed two additional times at approximately one year intervals, resulting in six temporally overlapping cohorts, each providing data for three adjacent ages (e.g., 12-year-old cohort, 13-year-old cohort, etc.). Preliminary analysis revealed that none of the age 12 children reported alcohol problems. This cohort (n = 488) was therefore excluded from all models due to lack of variability (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The cohort-sequential design combined data across the remaining cohorts (N = 3,116; ages 13-17 at wave 1) to approximate a traditional longitudinal design of adolescents from age 13 to 19 (see Figure 1), while minimizing potential cohort effects by estimating symptoms at each age based on multiple cohorts across different years (Duncan et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Cohort-sequential latent growth curve model for PTSD symptoms. Variables represent baseline symptom levels at age 13 (intercept) and age-related increases from 13 to 19 (slope). Solid age boxes represent collected data, whereas dashed lines reflect data missing by design. Asterisks indicate that pathways were allowed to vary freely, with the exception that regression weights at each age are equal across cohorts. An identical procedure was used to model the alcohol problems and interpersonal victimization variables. Cov = covariance; D = variance; M = mean; y.o. = year-old.

LGM provides estimates of means and variances for two primary metrics: intercept and slope. Intercept means reflect the initial level of symptom endorsement (i.e., baseline at age 13), whereas slope means reflect the rate of change of these symptoms over time (Duncan et al., 2006). In contrast, significant variances in intercept and slope indicate individual differences in baseline symptom level and rate of change over time, respectively, and support the analysis of potential predictors of these differences.

In LGM, regression weights for the intercept are all set to 1.0, which allows the intercept to be interpreted as the baseline level of a variable. For the slope, the first two regression weights (i.e., ages 13 and 14) are set to 0.0 and 1.0. Regression weights for all other ages are allowed to be estimated freely to capture both linear and nonlinear change over time2, with the restriction that regression weights at each age are equal across cohorts. The intercept and slope for each variable are set to covary, which is necessary for model specification (Duncan et al., 2006). Amos 18.0.2 structural equation modeling software was used for all analyses.

Three commonly used fit indices were used to estimate how well each model fit the data: chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Non-significant chi-square values indicate perfect fit, but this index is heavily impacted by sample size. CFI values > .95 and RMSEA values < .05 indicate excellent fit; CFI values > .90 and RMSEA values < .08 indicate acceptable fit (Schweizer, 2010).

A four-tier data analytic approach was adopted to examine the study’s primary hypotheses. In the first tier (Figure 1), separate PTSD symptoms, alcohol problems, and interpersonal victimization models were created to examine baseline levels (intercept) and changes with age (slope) for these variables and determine the need to examine potential predictors of these changes.

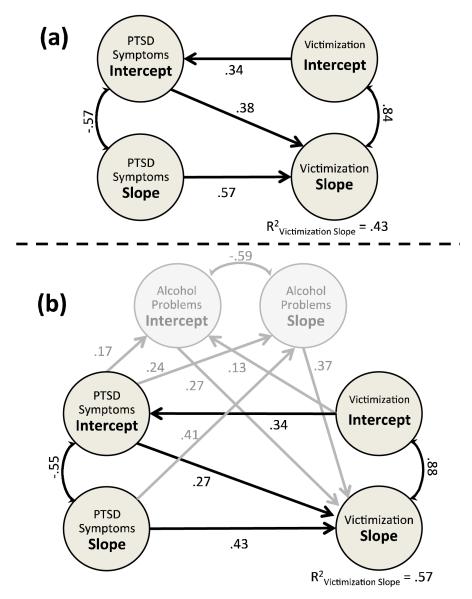

In Tier II, the PTSD symptoms and interpersonal victimization models were combined (Figure 2a). Cumulative interpersonal victimization by age 13 (baseline) was modeled to predict baseline PTSD symptoms, because the baseline interpersonal victimization variable reflects lifetime exposure, whereas the baseline PTSD symptoms variable reflects symptoms over the preceding year. In addition, baseline PTSD symptoms and age-related increases in PTSD symptoms were modeled to predict age-related increases in interpersonal victimization. Thus, regression weights for PTSD intercept and slope predicting interpersonal victimization slope reflect the impact of PTSD symptoms after accounting for previous interpersonal victimization.

Figure 2.

Results of the (a) Tier II and (b) Tier III models. PTSD symptoms and interpersonal victimization are modeled in Tier II (Figure 2a). Alcohol problems were added as a potential mediator of these relations in Tier III, and are shown in grey font (Figure 2b). Variables represent baseline symptom levels at age 13 (intercept) and age-related increases from 13 to 19 (slope). Single-headed arrow values reflect standardized β-weights; double-headed arrow values reflect correlations (r). Regression pathways for both models are all significant at p ≤ .002. Gender, ethnicity, and household income are included in both models but not depicted for readability.

In Tier III, the alcohol problems intercept and slope variables were added to the Tier II model as potential mediators, to examine the extent to which any increased risk for future victimization conveyed by baseline PTSD symptoms is attributable to the relation between PTSD symptoms and problematic alcohol use (Figure 2b). To examine the magnitude of any indirect (mediated) effect of PTSD symptoms on age-related increases in interpersonal victimization through alcohol problems, effect ratios were calculated. Effect ratios (indirect effect divided by total effect) estimate the proportion of each significant total effect attributable to the indirect effect and were used in lieu of the traditional “full” versus “partial” mediation tests as recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002).

In the final tier, we examined the extent to which any direct and indirect effects of PTSD symptoms on future alcohol problems and interpersonal victimization were attributable to specific clusters of PTSD symptoms (i.e., reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal).

Given that gender, ethnicity, and household income are correlates of violence exposure and mental health problems among youth (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Martinez & Richters, 1993; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006), these time-invariant predictors were tested in Tier I, and significant predictors were retained in the Tier II, III, and IV models. Gender was coded as boys = 0, girls = 1, and race/ethnicity was coded as Caucasian/non-Hispanic = 0, Non-Caucasian = 1. Annual household income was assessed using 10 ordered categories ranging from 1 (< $5000/year) to 10 (> $100,000/year). Ethnicity and household income were allowed to correlate (r = −.31) given evidence of continued socioeconomic inequality (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2007). Community type was also tested as a potential time-invariant predictor, coded as urban vs. suburban/rural3. Significance levels were set at p < .05 for all analyses; “trends” toward significance were not interpreted given the large sample size.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the interpersonal victimization, PTSD, and alcohol problems variables are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the interpersonal victimization variable by cohort, wave, and gender

| Interpersonal Victimization |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| Cohort | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| 13 | M | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.69 |

| SD | 0.96 | 0.79 | 1.03 | 1.44 | 1.22 | 2.02 | |

| %a | 20.2 | 18.1 | 21.5 | 21.9 | 21.8 | 24.1 | |

| 14 | M | 0.34 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.82 |

| SD | 1.03 | 1.60 | 1.17 | 1.77 | 1.49 | 1.84 | |

| %a | 20.8 | 28.4 | 19.5 | 31.7 | 22.5 | 32.4 | |

| 15 | M | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.90 |

| SD | 1.37 | 1.15 | 1.66 | 1.47 | 1.83 | 1.75 | |

| %a | 30.6 | 27.1 | 32.7 | 28.6 | 33.1 | 32.4 | |

| 16 | M | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 1.16 |

| SD | 1.43 | 1.53 | 1.75 | 2.01 | 1.96 | 2.28 | |

| %a | 33.9 | 27.0 | 33.7 | 31.9 | 40.5 | 32.2 | |

| 17 | M | 0.74 | 0.90 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.12 |

| SD | 1.49 | 1.88 | 2.10 | 2.14 | 2.54 | 2.15 | |

| %a | 33.6 | 35.5 | 37.3 | 36.8 | 34.0 | 34.5 | |

| Total | M | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.85 |

| SD | 1.43 | 1.68 | 1.54 | 1.96 | 1.77 | 1.91 | |

| %a | 26.4 | 25.7 | 27.3 | 28.0 | 28.8 | 29.0 | |

Values represents the percentage of youth that endorsed at least one victimization event.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for the PTSD and alcohol problems variables by cohort, wave, and gender

| PTSD |

Alcohol Problems |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Cohort | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| 13 | M | 0.74 | 1.35 | 0.79 | 1.94 | 0.73 | 1.76 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| SD | 1.28 | 2.25 | 1.60 | 2.67 | 1.75 | 2.74 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.34 | |

| %a | 2.4 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 7.3 | 2.7 | 11.5 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 5.8 | |

| 14 | M | 0.89 | 1.46 | 1.10 | 1.46 | 0.99 | 1.33 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| SD | 1.80 | 2.36 | 1.85 | 2.11 | 1.91 | 2.25 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.22 | |

| %a | 3.3 | 10.1 | 3.8 | 7.5 | 3.7 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 4.9 | |

| 15 | M | 1.12 | 1.76 | 1.13 | 2.11 | 1.15 | 1.75 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| SD | 1.74 | 2.23 | 1.99 | 2.91 | 2.29 | 2.67 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.41 | |

| %a | 4.7 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 12.4 | 5.2 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 11.1 | 6.5 | 8.5 | |

| 16 | M | 1.29 | 1.69 | 1.43 | 2.04 | 1.14 | 1.57 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.10 |

| SD | 1.73 | 2.28 | 2.34 | 2.69 | 2.13 | 2.72 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.32 | |

| %a | 3.9 | 12.5 | 6.3 | 10.1 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 14.7 | 8.4 | |

| 17 | M | 1.12 | 1.76 | 1.12 | 1.88 | 1.01 | 1.80 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| SD | 2.01 | 2.36 | 2.24 | 2.53 | 1.94 | 2.65 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.37 | |

| %a | 6.3 | 10.6 | 2.7 | 9.5 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 14.5 | 15.8 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 9.3 | 9.4 | |

| Total | M | 0.98 | 1.52 | 1.13 | 1.77 | 0.96 | 1.56 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| SD | 1.64 | 2.22 | 1.99 | 2.54 | 1.98 | 2.52 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.34 | |

| %a | 4.1 | 9.0 | 4.7 | 9.9 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 5.9 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.0 | |

For the PTSD variable, values represent the percentage of youth that met DSM-IV symptom criteria for PTSD. For the Alcohol Problems variable, values represent the percentage of youth that endorsed at least one alcohol use problem.

Tier I: Separate Interpersonal Victimization, PTSD, and Alcohol Problems Models

In Tier I, baseline levels and age-related changes in lifetime interpersonal victimization and past year PTSD symptoms and alcohol problems were modeled separately. Data for the separate Tier I models are not shown due to space limitations, but magnitude and significance levels are equivalent to those reported in Tiers II and III unless noted. All three models demonstrated adequate to excellent fit. Specifically, both the interpersonal victimization and PTSD symptom models fit the data well (both CFI > .95; both RMSEA < .04; both 90% CIRMSEA upper bounds ≤ .042). Model fit for the alcohol problems variable was slightly below acceptable levels for the CFI (.89) but excellent based on the RMSEA (.02, 90% CIRMSEA = .014 to .023); therefore, overall model fit was determined to be acceptable.

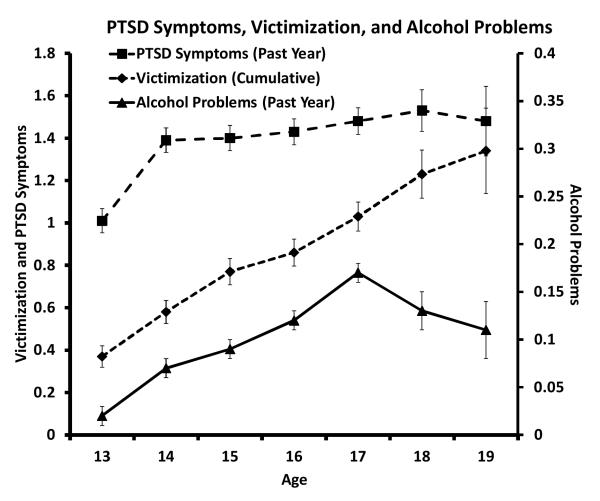

Intercept and slope were significant for all three separate models (all p values < .0005). Inspection of the slope means across models indicated that the quantity of interpersonal victimization, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol problems generally increased with age (all p values < .0005; see Figure 3). In addition, variances for intercept and slope were significant in all three models (all p values ≤ .0005), indicating significant individual differences in baseline levels and age-related changes for interpersonal victimization, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol problems.

Figure 3.

Cohort-sequentially modeled age-related changes in mean number of items endorsed for PTSD symptoms (squares), interpersonal victimization (diamonds), and alcohol problems (triangles). Error bars reflect standard error.

As noted previously, gender, ethnicity, household income, and community type were initially included as time-invariant predictors of all intercepts and slopes. Significant pathways were retained in all future models. Gender significantly predicted baseline PTSD symptoms (β = .18; p < .0005), and ethnicity predicted age-related changes in PTSD symptoms (β = .05; p < .03), interpersonal victimization (β = .08; p < .0005), and alcohol problems (β = −.07; p < .0005). In addition, household income predicted baseline victimization (β = −.09; p = .007) and age-related changes in victimization (β = −.12; p < .0005) and PTSD symptoms (β = −.08; p < .0005). Community type was not a significant predictor of any intercept or slope variables (all p values > .28). Collectively, the impact of these time invariant predictors on age-related increases in interpersonal victimization was modest (R2 = .02).

In sum, all three models fit the data adequately and were characterized by age-related increases in symptom endorsements. Gender differences were apparent only for PTSD symptoms at age 13 (girls endorsed more symptoms). Youth in households with a lower annual income were more likely to report a lifetime victimization experience by age 13. Age-related increases in interpersonal victimization and PTSD symptoms were slightly steeper for non-Caucasian relative to Caucasian/non-Hispanic adolescents and for adolescents in households with a lower annual income. Finally, age-related alcohol problem increases were slightly steeper for Caucasian/non-Hispanic relative to non-Caucasian adolescents. In addition, all three models featured significant individual differences in slope and intercept, indicating the need to examine potential predictors of these differences.

Tier II. Baseline PTSD Symptoms Predicting Future Interpersonal Victimization

In Tier II, the PTSD symptoms and interpersonal victimization models were combined to test the extent to which baseline PTSD symptoms predict age-related increases in interpersonal victimization after accounting for baseline interpersonal victimization (Figure 2a). The model fit the data well (CFI = .94, RMSEA = .03, 90% CIRMSEA = .027 to .032). All regression pathways were significant (all p values < .0005) and are described below.

Concurrent symptom relations (intercept predicting intercept, slope predicting slope)

Baseline interpersonal victimization was significantly associated with baseline PTSD symptoms (β = .34), as expected. In addition, age-related increases in PTSD symptoms were significantly related to age-related increases in interpersonal victimization (β = .57) after accounting for baseline interpersonal victimization and PTSD symptoms.

Temporal predictions (intercept predicting slope)

Importantly, baseline PTSD symptoms significantly predicted age-related increases in interpersonal victimization (β = .38), even after accounting for early interpersonal victimization. The interpersonal victimization slope variance remained significant (p < .0005), indicating that individual differences in age-related interpersonal victimization increases remained after accounting for baseline interpersonal victimization, baseline and age-related changes in PTSD symptoms, gender, ethnicity, and household income.

Collectively, the model explained 43% of the variance in age-related increases in interpersonal victimization (R2 = .43), relative to the 2% of variance explained by the Tier I victimization model. These findings indicate that early PTSD symptoms represent a significant risk factor for future increases in exposure to violent events, even after accounting for the impact of early interpersonal victimization, gender, ethnicity, and household income.

Tier III: Alcohol Problems as a Mediator of the PTSD-Interpersonal Victimization Association

In Tier III, the alcohol problems model was added to the Tier II model to examine the extent to which the increased risk for future interpersonal victimization conveyed by early PTSD symptoms was attributable to the association between PTSD symptoms and problematic alcohol use (Figure 2b). Specifically, the alcohol problems intercept and slope were added as potential mediators, such that baseline interpersonal victimization and PTSD symptoms predicted baseline alcohol problems. In addition, the PTSD symptoms slope and alcohol problems slope predicted the victimization slope. Finally, baseline PTSD symptoms and baseline alcohol problems predicted the victimization slope. The model fit the data well (CFI = .92, RMSEA = .03, 90% CIRMSEA = .026 to .029). All regression pathways among PTSD, alcohol problems, and victimization intercepts and slopes were significant (all p values < .0005) and are described below; all regression coefficients from time invariant predictors (gender, ethnicity, and household income) were significant at p ≤ .02 and highly similar in magnitude to the values reported in Tier I.

Concurrent symptom relations (intercept predicting intercept, slope predicting slope)

Baseline interpersonal victimization was associated with baseline PTSD symptoms (β = .34) and alcohol problems (β = .13). In addition, baseline PTSD symptoms were associated with concurrent alcohol problems (β = .17). Age-related increases in PTSD symptoms were related to age-related increases in alcohol problems (β = .41) and interpersonal victimization (β = .43). Finally, age-related increases in alcohol problems were related to age-related increases in interpersonal victimization (β = .37).

Temporal predictions (intercept predicting slope)

Baseline PTSD symptoms predicted age-related increases in both alcohol problems (β = .24) and interpersonal victimization (β = .27), even after accounting for baseline levels of these variables. In addition, baseline alcohol problems predicted age-related increases in interpersonal victimization (β = .27). Examination of the calculated indirect (mediated) effects [not shown in Figure 2b; indirect effect = total effect – direct effect] indicated that both baseline PTSD symptoms (β = .13) and age-related increases in PTSD symptoms (β = .15) exerted significant indirect effects on age-related increases in interpersonal victimization through baseline and age-related increases in alcohol problems, respectively.

Examination of the effect ratios (ER) revealed that the indirect effects accounted for only approximately one-fourth to one-third of the total effect of PTSD symptoms intercept and slope on interpersonal victimization slope (ER = .33 and .26, respectively)4. In other words, the impact of PTSD symptoms on age-related increases in interpersonal victimization is primarily a direct effect, indicating that PTSD symptoms represent a significant risk factor for additional interpersonal victimization above and beyond the risk conveyed by alcohol problems and prior interpersonal victimization (ΔR2 = .14 between Tier II and Tier III).

The interpersonal victimization slope variance remained significant, indicating that individual differences in age-related increases in interpersonal victimization remained after accounting for baseline victimization, gender, ethnicity, household income, and baseline and age-related changes in PTSD symptoms and alcohol problems. Collectively, the full model accounted for more than half of the variance in age-related increases in interpersonal victimization (R2 = .57).

Tier IV: PTSD Symptom Clusters

A final set of analyses was conducted to examine whether the relations between baseline PTSD symptoms and later alcohol problems and interpersonal victimization was attributable to specific PTSD symptom clusters (i.e., reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal). Symptom counts were obtained for each cluster at each wave in a manner identical to that described for overall PTSD symptoms. The PTSD symptom clusters were moderately correlated with each other across waves (r range: .32 to .39).

Each symptom cluster was separately substituted for the overall PTSD symptoms variable in the Tier III model. All three full models demonstrated excellent fit (all CFI ≥ .91; all RMSEA = .03; all 90% CIRMSEA upper bounds < .032). Results for all three separate PTSD Cluster models were highly similar to the overall PTSD symptoms model. In addition, the percentage of variance in age-related increases in interpersonal victimization was highly similar across models (R2 range: .50 to .57) and consistent with the results of the overall PTSD symptoms model (Tier III). Finally, ECVI indices were used to compare relative fit across these non-nested models and revealed highly similar values across all three cluster models and the overall model (ECVI range = .39 to .42; all 90% CI overlapped substantially and fell between .36 and .46). Collectively, these analyses suggest that the impact of PTSD symptoms on age-related increases in interpersonal victimization is attributable to PTSD symptoms as a whole, rather than to any particular cluster of PTSD symptoms.

Discussion

The current study examined relations among PTSD symptoms, alcohol problems, and interpersonal victimization using cohort-sequential LGM with a longitudinal sample of adolescents. Results indicate that PTSD symptoms, alcohol problems, and interpersonal victimization were all significantly related, both initially and in their patterns of age-related change. Specifically, exposure to interpersonal victimization by age 13 predicted concurrent PTSD symptoms and alcohol problems, and age 13 PTSD symptoms predicted concurrent alcohol problems. This is consistent with past research indicating that victimized youth are at elevated risk for experiencing PTSD symptoms and engaging in problematic alcohol use (Blumenthal et al., 2008). Further, these problems were significantly related throughout adolescence and, in general, the number of reported PTSD symptoms, alcohol problems, and victimization experiences significantly increased with age (see Figure 3). This is not surprising given that older youth have had more time during which they could have experienced a traumatic event and subsequently developed symptoms of PTSD. In addition, previous longitudinal research has documented increased alcohol use and related problems over the course of adolescence (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007; Li, Duncan, & Hops, 2001).

Findings also revealed small but significant relations between key demographic variables (i.e., youth gender, ethnicity, and household income) and the PTSD, alcohol problems, and interpersonal victimization outcomes. The patterns of association were consistent with what has been reported in past studies (Turner et al., 2006; Kilpatrick et al., 2003), and have been discussed previously in several comprehensive literature reviews (see Johnston et al., 2007; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1994; Trickey, Siddaway, Meiser-Stedman, Serpell, & Field, 2012).

The first study hypothesis was that PTSD symptoms would increase adolescents’ risk for future interpersonal victimization independently of the role of previous victimization. The results support this hypothesis, with age 13 (baseline) PTSD symptoms predicting significant age-related increases in victimization, even after accounting for the effects of earlier victimization experiences, gender, ethnicity, and household income. This finding is consistent with what has been reported in the adult literature (Cougle et al., 2009; Elwood et al., 2011; Messman-Moore et al., 2005; Orcutt et al., 2002) and extends this line of research to adolescents. Further, results indicate that the impact of PTSD symptoms on age-related increases in victimization is attributable to PTSD symptoms in general as opposed to any particular symptom cluster. These results add to the inconsistent literature regarding differential prediction of re-victimization as a function of PTSD symptom cluster (e.g., Cougle et al., 2009; Noll et al., 2006; Risser et al., 2006) and suggest that, for adolescents, an elevation in any of the three moderately correlated clusters confers risk for future victimization.

The second hypothesis was that alcohol problems would mediate the relation between PTSD symptoms and future victimization, over and above the impact of early victimization. Alcohol problems emerged as a partial mediator, such that the indirect effect of PTSD symptoms through increased alcohol problems accounted for approximately one-quarter to one-third of the total effect of PTSD symptoms on victimization. In addition, alcohol problems contributed to future victimization risk independently of PTSD symptoms. Collectively, the full model accounted for more than half of the variance in age-related increases in interpersonal victimization among youth. This represents a new finding in the adolescent victimization literature. Past studies have demonstrated that adolescents with PTSD are at higher risk for developing alcohol problems, perhaps because alcohol can serve the function of experiential avoidance of distressing emotional responses (Blumenthal et al., 2008). Further, alcohol use has been linked to victimization through impaired detection of danger cues (e.g., Davis et al., 2009) and the increased likelihood of delinquent peer association (Barnow et al., 2004; Fergusson et al., 2002). However, this is the first study of which we are aware that has identified alcohol problems as a mechanism linking PTSD symptoms with subsequent victimization in an adolescent sample. This finding is particularly salient for adolescents, given the rarity of alcohol problems during this developmental period and the strong association between victimization history and alcohol problems documented in past studies of this age group (Champion et al., 2004). Further, this finding fits well with past research documenting elevated rates of a cluster of risk-taking behaviors, including substance use, sexual risk taking, and impulsive behaviors, among victimized youth (e.g., Champion et al., 2004; Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynsky, 1997). Thus, one possible explanation for the results is that alcohol use problems are one of a number of risk-taking behaviors that put youth at high risk for revictimization.

Though alcohol problems provided a partial explanation, the relation between PTSD symptoms and subsequent victimization was primarily a direct effect, indicating that PTSD confers risk for victimization above and beyond the risk conferred by both alcohol problems and past victimization. Studies of adult samples provide potential explanations for this direct path from the three PTSD symptom clusters to future victimization. For example, PTSD may impede an adolescent’s ability to detect novel danger cues accurately, due to interference from reexperiencing symptoms, and/or overengagement of attentional resources to trauma reminders (Pineles et al., 2007, 2009). In addition, hyperarousal symptoms may lead to perception of risk that has high sensitivity for danger cues but low specificity for differentiating dangerous from non-dangerous situations (Barlow, 2002; Chu, 1992). Over time, these factors can lead to difficulty distinguishing adaptive fear from PTSD-related anxiety and may result in a lack of appropriate emotional and behavioral responses in the presence of novel, objectively dangerous situations. Each of these potential mechanisms deserves attention in future research.

Limitations

This study employed a large, national, random sample of adolescents to examine associations between PTSD symptoms, alcohol problems, and interpersonal victimization. However, despite these and other methodological strengths (e.g., controlling for measurement error and cohort effects, use of LGM mediation), the following limitations must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study relied exclusively on adolescent self-report interviews, which may be subject to retrospective report bias and shared method variance. The findings may have differed if data were collected from different sources; however, past studies have found adolescents to be more accurate reporters of their internalizing problems (e.g., PTSD) compared to parents or teachers (e.g., Cantwell, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1997). In addition, parent and adolescent symptom ratings are highly correlated over time, and self-reports appear to be more sensitive to early symptom emergence compared to parent reports (Cole et al., 2002).

A second limitation was the moderately high refusal and attrition rates and the use of telephone survey methodology that excludes youth residing in households without landline telephone service. However, refusal rates were similar to or lower than those reported in other studies (Cole et al., 2002), and missing data analysis indicated that attrition was either unrelated or weakly related to our primary variables of interest. Further, the pattern of age-related symptom changes for all three syndromes was consistent with the literature (Johnston et al., 2007; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010). Nevertheless, it is impossible to know whether non-completers differed from completers during waves at which the former were not assessed. Regarding telephone survey methodology, epidemiological data indicate that only 7.3% of U.S. children lived in households without a landline phone (i.e., households that had only cellular service or no phone service) in the first half of 2005 (Blumberg & Luke, 2008), which was the year of initial study recruitment. It should be noted that this national percentage increased over the study period, with 16.5% of children living in households without landlines by the second half of 2007 (Blumberg & Luke, 2008). Thus, although the exclusion of adolescents living in households without landlines has the potential to bias results, this issue was more prevalent during the latter part of the study, when it would have a greater influence on attrition (see discussion above) than recruitment. In terms of assessment, the measure of alcohol use problems utilized in the study was conservative, as it 1) focused on problems related to alcohol use rather than alcohol use itself, and 2) relied on adolescents to identify and report on the negative effects of their own alcohol use. However, these questions were designed to be as behaviorally specific as possible in order to decrease reporting bias. Finally, third variable explanations for our finding that PTSD symptoms predict and temporally precede future victimization cannot be ruled out conclusively, despite our control for gender, ethnicity, household income, prior victimization, and alcohol problems, as well as previous research demonstrating that re-victimization risk was independent of family demographics, stressful life events, and delinquency (Finkelhor et al., 2007). For example, certain aspects of an adolescent’s proximal environment (e.g., residing with chronically abusive parents and/or in a high-crime neighborhood) might make it difficult to escape repeat victimization and also increase the likelihood for developing PTSD.

Clinical and Research Implications

The current study indicates that PTSD symptoms serve as a significant risk factor for subsequent alcohol problems and interpersonal victimization among adolescents, even after accounting for previous victimization, current alcohol problems, gender, ethnicity, and household income. In addition, alcohol problems conferred additional victimization risk both secondary to and independently of PTSD symptoms. Collectively, PTSD symptoms and alcohol problems accounted for 57% of the variance in future interpersonal victimization, independent of the impact of early victimization. Thus, the current findings suggest that PTSD behaviors/symptoms, which are frequently described by patients as methods of maintaining safety in a dangerous environment (e.g., avoidance of, or hypervigilance during, perceived high-risk situations), have the opposite effect – significantly increasing the likelihood that the adolescent will experience additional interpersonal violence/victimization. In light of these findings, it is recommended that clinicians screen for PTSD symptoms and problematic alcohol use when adolescents present for treatment and, when detected, target these risk factors through the delivery of evidence-based interventions (see www.abct.org/sccap/ for a list of established treatments for adolescent clinical problems, including PTSD and substance use). Results from this community sample suggest that treating PTSD symptoms and alcohol problems might decrease the risk of future victimization. However, this hypothesis needs to be tested with a clinical sample. Future research with adolescents should also focus on identifying additional mechanisms through which PTSD confers risk for future victimization. Given that all three PTSD symptom clusters appear to play a role in this increased risk, multiple mechanisms should be considered, including impaired differentiation of adaptive fear versus maladaptive anxiety, impaired discrimination between objectively dangerous versus nondangerous situations, and inappropriate allocation of attentional resources. Another area for future research is the exploration of co-occurring depressive symptoms, additional high-risk behaviors (e.g., illicit drug use, high-risk sexual behavior), exposure to non-interpersonal trauma, as well as treatment effects – all of which are likely mechanisms through which PTSD symptoms impact risk for future victimization.

Footnotes

A few studies have reported positive associations between general measures of distress (e.g., global anxiety, depression) and future victimization among youth (Cuevas, Finkelhor, Clifford, Ormrod, & Turner, 2010; Lindhorst, Beadnell, Jackson, Fieland, & Lee, 2009). In addition, one study examined PTSD symptoms as a risk factor for assault in a mixed group of adults and adolescents (Noll, Trickett, Susman, & Putnam, 2006). However, studies have not yet examined the association between PTSD and revictimization in an exclusively adolescent sample.

Allowing these slope weights to be estimated freely resulted in significantly improved model fit relative to forcing a linear or quadratic solution for all models tested (all chi-square difference tests p < .0005). Thus, positive slope values reflect a general increase in symptom reporting with increasing age, rather than a strictly linear increase (see Figure 3).

Community type was also tested as an ordered categorical variable based on distance from urban areas (0 = urban, 1 = suburban, 2 = rural). Results were unchanged when this variable was substituted for the dichotomous categorical variable described above.

Effect ratios are computed as the indirect effect divided by the total effect (direct effect + indirect effect). For example, the indirect effect of PTSD intercept on victimization slope reported above (β = .13) was divided by the sum of the PTSD intercept to victimization slope direct effect shown in Figure 2b (β = .26) and the indirect effect reported above to calculate the percentage of the total effect of PTSD intercept on victimization slope attributable to the indirect effect of PTSD intercept through alcohol problems [.13/(.27 +.13) = .33].

Contributor Information

Michael R McCart, Medical University of South Carolina Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences 67 President St., Suite MC406, MSC 861 Charleston, South Carolina 29425 mccartm@musc.edu.

Kristyn Zajac, Medical University of South Carolina zajac@musc.edu.

Michael J Kofler, University of Central Florida Michael.Kofler@ucf.edu.

Daniel W Smith, Medical University of South Carolina smithdw@musc.edu.

Benjamin E Saunders, Medical University of South Carolina saunders@musc.edu.

Dean G Kilpatrick, Medical University of South Carolina kilpatdg@musc.edu.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM. From child victim to adult victim: A model for predicting sexual revictimization. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:28–38. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barnow S, Schultz G, Lucht M, Ulrich I, Preuss U-W, Freyberger H-J. Do alcohol expectancies and peer delinquency/substance use mediate the relationship between impulsivity and drinking behavior in adolescence? Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2004;39:213–219. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Wireless substitution: Early release of estimates based on data from the National Health Interview Survey, July – December 2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Retrieved April 8, 2010]. 2007. from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/wireless 200705.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal H, Blanchard L, Feldner MT, Babson KA, Leen-Feldner EW, Dixon L. Traumatic event exposure, posttraumatic stress, and substance use among youth: A critical review of the empirical literature. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2008;4:228–254. [Google Scholar]

- Boals A, Schuettler D. PTSD symptoms in response to traumatic and non-traumatic events: The role of respondent perception and A2 criterion. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. 2nd Ed Routledge; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion HIO, Foley KL, DuRant RH, Hensberry R, Altman D, Wolfson M. Adolescent sexual victimization, use of alcohol and other substances, and other health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu JA. The revictimization of adult women with histories of childhood abuse. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research. 1992;1:259–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. How research on child maltreatment has informed the study of child development: Perspectives from developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1989. pp. 377–431. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Tram JM, Martin JM, Hoffman KB, Ruiz MD, Jacquez FM, Maschman TL. Individual differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescence: A longitudinal investigation of parent and child reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Resnick H, Kilpatrick DG. A prospective examination of PTSD symptoms as risk factors for subsequent exposure to potentially traumatic events among women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:405–411. doi: 10.1037/a0015370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas CA, Finkelhor D, Clifford C, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Psychological distress as a risk factor for re-victimization in children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Stoner SA, Norris J, George WH, Masters NT. Women’s awareness of and discomfort with sexual assault cues: Effects of alcohol consumption and relationship type. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:1106–1125. doi: 10.1177/1077801209340759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith J. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2006. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2007. U.S. Census Bureau. Current population reports, series P60-233. [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Arias I, Thompson MP, Basile KC. Childhood victimization and subsequent adult victimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence & Victims. 2002;17:639–653. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve Modeling. 2nd Ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elwood LS, Smith DW, Resnick HS, Gudmundsdottir B, Amstadter AB, Hanson RF, Kilpatrick DG. Predictors of rape: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:166–173. doi: 10.1002/jts.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: Evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1997;21:789–803. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, Horwood J. Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: A fixed effects regression analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;39:419–430. doi: 10.1023/a:1015774125952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Characteristics of crimes against juveniles. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2000. (NCJ 179034) [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Re-victimization patterns in a national longitudinal sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:479–502. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormrod RK, Hamby SL. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1411–1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Hauf AC, Paradis AD, Wasserman MS, Langhammer DM. Comorbidity of substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders in a community sample of adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:253–262. doi: 10.1037/h0087634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashima PY, Finkelhor D. Violent victimization of youth versus adults in the National Crime Victimization Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:799–820. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway LM, Boals A, Banks JB. PTSD symptoms and dominant emotional response to a traumatic event: An examination of DSM-IV Criterion A2. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2010;23:119–126. doi: 10.1080/10615800902818771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2006: Volume I, secondary school students. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2007. (NIH Publication No. 07-6205) [Google Scholar]

- Karam EG, Andrews G, Bromet E, Petukhova M, Ruscio AM, Salamoun M, Kessler RC. The role of criterion A2 in the DSM-IV diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence. Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. The National Women’s Study PTSD Module. National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina; Charleston, SC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Duncan TE, Hops H. Examining developmental trajectories in adolescent alcohol use using piecewise growth mixture modeling analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:199–210. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Beadnell B, Jackson LJ, Fieland K, Lee A. Mediating pathways explaining psychosocial functioning and revictimization as sequelae of parental violence among adolescent mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:181–190. doi: 10.1037/a0015516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Richters JE. The NIMH community violence project II: Children’s distress symptoms associated with violence exposure. Psychiatry. 1993;56:22–35. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Brown AL, Koelsch LE. Posttraumatic symptoms and self-dysfunction as consequences and predictors of sexual revictimization. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:253–261. doi: 10.1002/jts.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, Susman EJ, Putnam FW. Sleep disturbances and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:469–480. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3rd Ed McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt H, Erickson DJ, Wolfe J. A prospective analysis of trauma exposure: The mediating role of PTSD symptomatology. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:259–266. doi: 10.1023/A:1015215630493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Shipherd JC, Mostoufi SM, Abramovitz SM, Yovel I. Attentional biases in PTSD: More evidence for interference. Behavior Research & Therapy. 2009;47:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Shipherd JC, Welch LP, Yovel I. The role of attentional biases in PTSD: Is it interference or facilitation? Behavior Research & Therapy. 2007;45:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risser HJ, Hetzel-Riggin MD, Thomsen CJ. PTSD as a mediator of sexual revictimization: The role of reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:687–698. doi: 10.1002/jts.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Rheingold AA, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Galea S. Comparison of two widely used PTSD-screening instruments: Implications for public mental health planning. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:699–707. doi: 10.1002/jts.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL. Violent victimization and offending: Individual-, situational-, and community-level risk factors. In: Reiss AJ, Roth JA, editors. Understanding and preventing violence, volume 3: Social Influences. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1994. pp. 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer K. Some guidelines concerning the modeling of traits and abilities in test construction. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2010;26(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Davis JL, Fricker-Elhai AE. How does trauma beget trauma? Cognitions about risk in women with abuse histories. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9:292–303. doi: 10.1177/1077559504266524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickey D, Siddaway AP, Meiser-Stedman R, Serpell L, Field AP. A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:122–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Najdowski CJ, Filipas HH. Child sexual abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use: Predictors of revictimization in adult sexual assault survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2009;18:367–385. doi: 10.1080/10538710903035263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Dutton MA. Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]