Abstract

Glick-Fiske's (1996) Ambivalent Sexism Inventory(ASI) and a new Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage (GRIM) inventory examine ambivalent sexism toward women, predicting power-related, gender-role beliefs about mate selection and marriage norms. Mainland Chinese, 552, and 252 U.S. undergraduates participated. Results indicated that Chinese and men most endorsed hostile sexism; Chinese women more than U.S. women accepted benevolent sexism. Both Chinese genders prefer home-oriented mates (women especially seeking a provider and upholding him; men especially endorsing male-success/female-housework, male dominance, and possibly violence). Both U.S. genders prefer considerate mates (men especially seeking an attractive one). Despite gender and culture differences in means, ASI-GRIM correlations replicate across those subgroups: Benevolence predicts initial mate selection; hostility predicts subsequent marriage norms.

Keywords: Hostile sexism, Benevolent sexism, Mate selection, Gender roles, Marriage norms

Introduction

According to Glick and Fiske's (1996, 2001) Ambivalent Sexism Theory, sexism is a multidimensional construct that encompasses two sets of sexist attitudes: hostile and benevolent. While hostile sexism communicates a clear antipathy toward women, benevolent sexism takes the form of seemingly positive but in fact patronizing beliefs about women. Glick and Fiske describe benevolent sexism as a set of attitudes that are sexist in viewing women stereotypically and restricting their roles, but that are subjectively positive in feeling tone and also tend to elicit behavior typically categorized as prosocial (e.g., helping) or intimacy seeking (e.g., self-disclosure). Its underpinnings lie in traditional stereotyping and masculine dominance (e.g., the man as the provider and woman as his dependent), and its consequences are often damaging.

This study focuses on revealing the core of ambivalent sexism in marriage: It investigates a series of power-related norms in people's ideology about marriage, tying the traditional role of women to family, limiting the career development and ambitions of women, giving them disproportionate housework and nurturing responsibility, and identifying women as obedient and dependent in supporting their husbands even if they sacrifice their own careers. We suggest that, for ambivalent sexists, imbalanced marital power is influenced by two mechanisms: enacting male dominance prior to marriage by mate selection criteria, and maintaining male dominance during marriage by power-related gender-role norms for both spouses. The study goes beyond previous research in assessing power-related gender-role opinions about marriage and relating them to ambivalent sexism. This study also goes beyond previous work by comparing Chinese and American samples, which might be expected to differ for a variety of cultural reasons.

Ambivalent Sexism Theory

Contrary to the traditional, typical definition of sexism as just antipathy toward women, Glick and Fiske (1996, 2001) presented a theory that sexism toward women is usually ambivalent, involving not only hostile sexism but also benevolent sexism. The theory posits that the relations between the genders are characterized by the coexistence of male dominance in society and intimate interdependence, hence eliciting ambivalent sexism. On the one hand, male predominance in economic, political, and social institutions supports hostile sexism, which characterizes women as inferior and incompetent. On the other hand, sexual reproduction makes men and women intimate and highly interdependent with each other, this relationship creating benevolent sexism, which characterizes women as needing to be protected. The relevant research supports both positive and negative attitudes that serve to justify unequal gender relations.

Glick and Fiske (1996, 1999) developed a scale to measure hostile and benevolent sexism toward women (the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory [ASI]). This 22-item measure assesses individual levels of hostile and benevolent sexism toward women. Whereas HS is a single factor (though originally viewed as having three components), BS includes three factors: protective paternalism (chivalry toward women), complementary gender differentiation (stereotypic roles for women), and heterosexual intimacy (believing men and women are incomplete without each other).

How do these subjectively hostile and benevolent attitudes co-exist? As combined positive and negative feeling, ambivalent sexism might seem to induce cognitive conflict. Actually, ambivalently sexist men avoid this inconsistency (Glick et al. 1997); they split women into “good” and “bad” subgroups that embody the positive and negative aspects of sexist ambivalence. This clear-cut distinction leads to an internally consistent attitude: Some types of women (career women, feminists, lesbians) deserve hostile treatment (Eagly and Karau 2002), whereas others (housewives and mothers) should be treated with benevolence. The subgroups of women reflect traditional power relationships and gender roles. The objects of benevolent sexism are those women who obey traditional gender roles with no threat to the power of men; the objects of hostile sexism are those whose behavior opposes traditional gender roles and threatens the dominance of a traditional patriarchy. Thus, benevolent sexism should be especially obvious in beliefs about complementary gender relationships, such as ideology about marriage.

Research and Theories About Marital Power

A widely accepted definition of marital power is “the potential ability of one partner to influence the other's behavior,” which is manifested “in the ability to make decisions affecting the life of the family” (Blood and Wolfe 1960, p. 11). Since then, broad investigations of the power relations between men and women reveal that the sexual asymmetry favors men in many societies (Kim and Emery 2003; Warner et al. 1986), and in some cultures the inequality in families is extreme.

Resource theory and patriarchal culture theory are the two basic theories that researchers usually use to understand family power. The basic tenet of resource theory is that each spouse is dependent based on how much that spouse contributes valuable resources to the marriage (Blood and Wolfe 1960; Blumstein and Schwartz 1983; Brayfield 1992; Gillespie 1971; Kulik 1999; McDonald 1980; Safilios-Rothschild 1967; Scanzoni and Szinovacz 1980; Whyte 1990). As the family breadwinner, the husband usually possesses relatively higher socioeconomic resources, and correspondingly usually acts as the important family decision maker.

Patriarchal norms theory emphasizes the influence of patriarchal culture on family power (Blumberg and Coleman 1989; Ferree 1990). In fully patriarchal societies that have not been influenced by egalitarian norms, marriages will be almost uniformly husband-dominated, regardless of either the husband's or the wife's resources. Indeed, a growing body of research has substantiated that gender-role ideology exerts a great influence on marital power, beyond the impact of structural resources (Goldscheider and Waite 1991; Greenstein 1996; Kamo 1988; Kulik 1999; Scanzoni and Szinovacz 1980; Wilkie et al. 1998).

This study views the resource theory and the patriarchal norms theory as two related theories that interact within family power structures. Resources define the dominant status in a family and elicit patriarchal norms in marriage; patriarchal norms enhance imbalanced resources between partners and increase patriarchal norms, and maintain the family power imbalance (male dominance) even when some women achieve greater incomes. As a kind of prejudiced gender-role ideology toward women, according to patriarchal norms theory, ambivalent sexism should relate to patriarchal norms that maintain power imbalance between partners.

Power-Related Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage

Traditional values in heterosexual dating and marriage relate to prescriptive gender-role norms about what men and women “should do” or “should be” and “should not do” or “should not be.” Many norms follow a basic rule that men are dominant in status and power, so they should be the protective provider, while women should be obedient and dependent. The main norms involve at least two such inter-related aspects: dominant or submissive traits in mate selection and gender-role norms in marriage. The main principles of gender role norms specifically related to dominance in marriage involve at least four such aspects: dominance or submission in the family, career competition or sacrifice, nurturing of the children and distribution of the housework, and attitudes about family violence toward women.

Dominant or Submissive Traits in Mate Selection

Some research on the criteria for an individual's mate selection indicate great gender differences between men and women (Fisman et al. 2006; Gutierres et al. 1999; Sprecher et al. 1994). Some evolutionary psychologists have argued that men have developed a preference for mates who show signs of fertility (e.g., youth, health, and sexual maturity) and that women have developed a preference for mates who control resources (Buss and Schmitt 1993; Cunningham 1986; Kenrick and Trost 1989). Related to this point, some research suggests that sex differences in mate preference for social dominance and physical attractiveness are fairly robust across samples and methodologies (Jensen-Campbell et al. 1995; Feingold 1990, 1992).

Regarding gender differences in mate selection, social psychologists who adopt the socio-cultural perspective have explained these differences in terms of culturally relative socialization pressures (e.g., Eagly and Wood 1999; Howard et al. 1987). That is, men's greater preference for a partner who is attractive and young and women's greater preference for a partner who can provide material wealth can be explained by traditional sex-role socialization and the poorer economic opportunities for women.

Overall, whether due to evolutionary or socio-cultural development, the gender difference in mate selection criteria tends to indicate that men should possess some stereotypic socially dominant provider-related resources such as high status, high ability, intelligence, economic success, etc. Accordingly, women should be stereotypically attractive, submissive, and obedient. This study explores the relationship of ambivalent sexism with such mate selection criteria, in a context that focuses specifically on marriage.

Dominance or Submission in the Family

The right of decision-making in a family reflects the power dynamics within that family. Most of the related research indicates that, due to men's resource advantage or socio-cultural influence, a traditionally accepted marriage norm is for the husband to be independent and the decision-maker, while the wife remains submissive and dependent (Kulik 1999; Lueptow et al. 1989). The present study also explores the relationship of ambivalent sexism to the traditional gender-role norm of the husband as the family decision-maker.

Career Competition or Sacrifice

Traditionally, husbands have exercised greater control in marriage, and this power is mainly linked with the income and status that men have provided as the breadwinner. In the modern world, one's career is the main source of socioeconomic status. Beyond the power imbalance created by mate selection criteria, different attitudes toward spouses’ career development may also enhance this imbalance. These differences arise when sexists accept the norm that the wife should support the husband's job even at the cost of her own job, while the husband is not required to support the wife's job to the same extent (Kinnier et al. 1991). In the present study, we also explore the relationship of ambivalent sexism with the traditional gender-role norm that the wife should sacrifice her career to support her husband's.

Male Success and Distribution of Housework

Tending to domestic tasks, including nurturing children and doing housework, is generally thought in traditional gender-role ideology to be more the woman's responsibility than the man's. This frees up men to pursue success in their stereotypic sphere outside the home. Ironically, according to resource and exchange theories, breadwinning for men and domestic labor for women induce men's greater power and women's lower status in the family (Coltrane 1996; Ferree 1990). Because women's domestic work is unpaid, it is undervalued and taken for granted as a basic duty. The present study also explores the relationship of ambivalent sexism with traditional gender-role norm for the wife to be responsible for child-rearing and household chores, in order to facilitate the husband's success outside the home. Previous work (Eastwick et al. 2006) relates ambivalent sexism in nine nations to men's preferences for a mate who is a good cook and housekeeper (and to women's preferences for a mate who is a good provider). We expand on those single-item measures here.

Family Violence Against Women

Family violence against women is a long-standing and common problem (Cousineau and Rondeau 2004; Gondolf 2004). In a sense, it reflects the physical power of men over women. Previous related research found that marital power and conflict in particular were strongly correlated with violence; a male-dominant marital power structure is highly correlated with husband-to-wife violence (Coleman and Straus 1990; Kim and Emery 2003; Sartin et al. 2006). As an extreme hostile behavior, we predict in the present research that hostile sexism is related to family violence against women.

Ambivalent Sexism

Benevolent sexism should be particularly influential in mate selection and marriage norms because it endorses soft control over women's roles as subordinate assistants and men's roles as authoritative providers. It submerges the intimate hierarchy. In a previous study emphasizing the dating context, American undergraduates preferred the romantic ideal of a traditional partner, to the extent they endorsed benevolent sexism, but not hostile sexism (Lee et al., under review). Hostile sexism should have less impact overall, especially in mate selection, where women still have a choice. In marriage norms, our emphasis here, men can afford to express hostile sexism; women are lower on hostile sexism in general because it is against their interests.

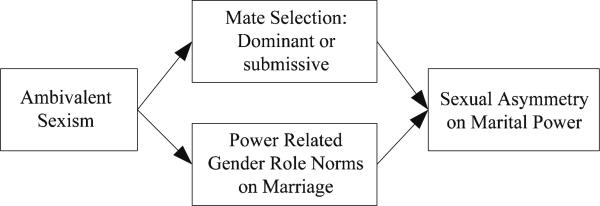

The main purpose of this study is to explore the core of ambivalent sexism in marital norms tying women to a disadvantaged subgroup. A basic premise of the current research is that two main mechanisms of ambivalent sexism reflect marital power: enacting male dominance at the beginning of a marriage by mate selection criteria and maintaining male dominance during marriage by power-related gender-role norms in marriage. Figure 1 shows the basic idea of these two mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Two main mechanisms of ambivalent sexism affecting marital power.

Gender Differences

In general, men score higher on the ASI, both HS and BS, than women, which is not surprising given their stake in a traditionally sexist dominant role; we would expect to replicate that finding here, especially for HS. Women sometimes outscore men on BS in countries with the higher overall sexism scores (Glick et al. 2000). Of more interest here is the dynamic of ambivalent sexism regarding gender-role ideology in marriage.

Cultural Differences

Chinese and American samples provide an important comparison for a number of reasons. First, cultural psychology has focused so far on individualism-collectivism, primarily comparing Western and East Asian samples (Heine and Buchtel 2009). An individualist culture might have weaker ideology prescribing gender roles in marriage because people would be relatively more autonomous and less interdependent than in a more collectivist society. Second, individualist societies have higher relational mobility (Heine and Buchtel 2009), so again the prescriptions might be looser. Finally, prior research suggests that developing countries have higher sexism scores (e.g., Glick et al. 2000, 2004) and might therefore show more traditional gender dynamics than more developed countries (Eastwick et al. 2006; Lee et al., under review).

On a more speculative note, some literature (including the ASI) suggests that sexism reflects gender competition between men and women. And this competition may relate to resource scarcity and the shortage of social/career development chances. China is a developing country, and perhaps economic and power concerns are more important in a rapidly changing, developing country than in a more stable, developed country. Perhaps the gender competition in a developing area can be relatively more severe than in a more developed area. In addition, China specifically has a long history of male-female hierarchy built explicitly into traditional Confucian philosophy (Bond and Smith 1996), so this might contribute to cultural differences as well.

The fundamental dynamics of male societal dominance and male-female interdependence should be cultural universals (Rudman and Glick 2008). Although the absolute degrees of gender dominance and ambivalent sexism differ across cultures (Glick et al. 2000, 2004), one might expect culture to interact with these variables to create distinct versions of these phenomena (Bond and Smith 1996).

The cultural main effects hypothesis would posit that culture merely raises and lowers the sheer degrees of each kind of sexism and also of traditional marital opinions. For example, Chinese women, like American women, worry about their physical appearance presumably because it matters in both cultures, but it might still matter more in the U.S. The cultural interaction hypothesis would posit that hostile sexism operates more strongly in a culture with more traditional gender roles, whereas benevolent sexism operates more strongly in a culture with more egalitarian gender roles because it is a more subtle form of sexism. One previous study, using completely different measures, found that Chinese respondents were both more idealistic and pragmatic in their relationship beliefs (Sprecher and Toro-Morn 2002). In contrast, the cultural similarities hypothesis would emphasize China's rapid transition to the developed world, and the respondents as students might especially reflect a more individualist ideology characteristic of more developed countries.

BS-HS Differences

BS should relate broadly to mate preferences because BS predicts attitudes toward women in traditional roles such as intimate relationships. For men—and to the extent that they subscribe to it, for women—BS also should relate to gender-specific mate preferences, men's preferences for female subordination and women's preferences for male dominance in mate selection. Moreover, BS being a softer form of control should make it easier for women to accept at the mate-selection stage, so it should predict mate selection criteria for both genders.

HS on the other hand is a more raw form of power-related ideology and usually predicts attitudes toward nontraditional women. Here it would predict control over wives so they do not violate traditional expectations, once committed to marriage. To the extent it predicts marriage norms, HS should do so more strongly for men and for norms concerning sheer dominance, such as marital violence.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1

In men's mate selection criteria, BS will positively relate to female submissive characteristics such as being home-oriented and deferential.

Hypothesis 2

In women's mate selection criteria, BS will positively relate to male dominant characteristics such as capability to provide.

Hypothesis 3

For men and women, HS will positively relate to traditional imbalanced gender role norms in marriage. High HS participants will endorse male dominance in family decisions, the belief that the wife should assist her husband's career even at the cost of her own career, and that the wife should do more housework and be more responsible for nurturing children than is the husband. High HS participants in particular will tend to have relatively higher agreement on family violence toward women than low HS groups. BS may show weaker versions of these effects.

Method

Participants

Chinese Sample

The participants were 552 undergraduate and graduate students (266 male, 269 female; mean age=20.83 years; all unmarried; 55.6% participants had been involved in a serious or casual relationship.). All were students at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology but originally from different places throughout China. Respondents were either natural or social science majors, and completed the survey in their classroom.

American Sample

The participants were 252 Princeton University undergraduates (92 male, 160 female; mean age = 20.72 years; all unmarried; 62.3% participants had been involved in a serious or casual relationship.). Most participants were psychology majors, and completed the survey in a psychology lab.

Measure

All participants completed a survey entitled “Dating and Marriage Values Survey” that included the ASI (22 items); the other part formed the initial pool of 49 items from which the power-related Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage (GRIM) questionnaire was developed.

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI)

Glick and Fiske's Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) includes 22 items in two subscales: Hostile Sexism (HS, e.g., “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men”; “Most women fail to appreciate fully all that men do for them”) and Benevolent Sexism (BS, e.g., “Women should be cherished and protected by men”; “Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess”). The translation of the Chinese ASI entailed three steps: first, a Chinese psychological professional translated it from English into Chinese, then a professional English-Chinese translator back-translated it from Chinese to English, and then the former Chinese psychological professional compared the back-translated English copy with the original English copy, modifying the final Chinese translated copy. All the items were rated on a six-point scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly. The Cronbach α of HS and BS subscales in this study are acceptable at .75 and .74.

Power-Related Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage (GRIM)

To measure power-related gender-role opinions about marriage, we compiled a 49-item preliminary questionnaire. Most of the items had been used by the first author (Chen 1999) in research on traditional values and norms about dating and marriage. Besides these items, following some related research (Fisman et al. 2006; Gutierres et al. 1999; Yue et al. 2005; Xu 2000), we also added several new items related to gender-role, power, and equality ideology in close relationships, thus creating the current questionnaire. This GRIM survey consisted of two parts. Part 1 mainly related to mate-selection criteria, including 30 items about power- and equality-related spouse selection criteria. All the items were rated on a five-point scale ranging from least important to extremely important.

Part 2 was 19 items (including four reversed items) about power-related gender-role norms in marriage, including four factors: dominance or submission in the family, career competition or sacrifice, nurturing the children and distributing the housework, and family violence against women. All the marriage-norms items were rated on a six-point scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly.

Results

Development of New Measures: GRIM

First, we address the psychometrics of the two parts of the new Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage measure, then we will turn to country and gender mean differences, and finally we will describe how ASI predicts the GRIM, our central goal here.

Reliability and Factor Analysis of Mate-Selection Criteria

We combined the samples from China and the U.S. to test the reliability and structure of the questionnaires because our ultimate aim is to use these measures as outcomes predicted by the ASI. In country-specific analyses, similar factor structures emerge, but because these theory-driven items were generated a priori, they are not maximally sensitive to cultural differences (see Lee et al., under review, for a more data-driven, culturally-tuned approach to dating-relationship ideals).

Using item-total correlations as the first-step filter, all 30 mate-selection items relate to the mean of the total items. So then we used exploratory factor analysis, with oblique rotation; the break in the scree plot and number of eigenvalues greater than one suggested a four-factor solution, accounting for 45.32% of the total variance. Selecting items with absolute loading values greater than .45 (see Table 1 for full wording of specific items), the first factor was mainly related to provider ability; the second factor was mainly related to consideration and respect for each other; the third factor was mainly related to submission and home-oriented values; the fourth factor was mainly related to appearance and interests. All four factors have acceptable reliabilities as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis with mate selection criteria.

| Items | Provider ability | Consideration and respect | Home-oriented and submissive | Appearance and attractive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Good appearance | .74 | |||

| A2 Enterprise | .65 | |||

| A3 Responsibility | .45 | |||

| A4 Thin | .68 | |||

| A5Appreciates communication | .62 | |||

| A6 Muscular | .59 | |||

| A7 Well-educated | .50 | |||

| A8 Consideration | .62 | |||

| A9 Sense of humor | .52 | |||

| A10 Has good job | .73 | |||

| A11 Value equality | .46 | |||

| A12 Home orientation | .67 | |||

| A13 Attractive | .59 | |||

| A14 Good provider | .73 | |||

| A15 Respect each other | .70 | |||

| A16 Holds traditional values | ||||

| A17 Protects me | .69 | |||

| A18 In control | .47 | |||

| A19 Ambitious | .62 | |||

| A20 Submissive | .71 | |||

| A21 Has similar hobbies or interests | ||||

| A22 High income, economic security | .75 | |||

| A23 High ability | .69 | |||

| A24 Gentleness | .45 | |||

| A25 Love sports | .49 | |||

| A26 Has similar values | .53 | |||

| A27 Good home maker | .76 | |||

| A28 Intelligent | .54 | |||

| A29 Independent | ||||

| A30 Friend | .67 | |||

| Cronbach α | .79 | .74 | .71 | .71 |

Reliability and Factor Analysis of Gender-Role Norms in Marriage

Again, we used item-total correlations as the first-step filter. All 19 items relate to the total-item mean. Then we used exploratory factor analysis, with oblique rotation (after deleting the four reversed items because of unreliability); the break in the scree plot and number of eigenvalues greater than one suggested a four-factor solution, accounting for 50.97% of the total variance. Selecting items with absolute loading values greater than .45 (see Table 2 for items), the first factor was mainly related to assisting and upholding the husband's authority; the second factor was mainly related to women nurturing children and doing housework, with men achieving success; the third factor was mainly related to attitudes about family violence toward women; the fourth factor reflected male dominance and shame at failure. All four factors have acceptable reliabilities, as indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis with gender role norms on marriage.

| Items | Assist and uphold | Success and housework | Family violence | Male dominance and shame |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1. The man who is not successful in career is at a disadvantage in his family. | .65 | |||

| B2. The man should be the King in the family | .49 | |||

| B3. Success children comes naturally to a mother. | ||||

| B4. The wife should spare no efforts to support her husband's career even at the price of her own career. | .72 | |||

| B5. The relationship wouldn't last long if the wife is doing better in her career than her husband. | .70 | |||

| B6. A good man should be able to provide a comfortable life for the woman he loves. | .76 | |||

| B7 Assisting the husband's career comes naturally to a wife. | .75 | |||

| B8. The man who fears his wife could never achieve anything significant. | .61 | |||

| B9. A woman who does not do housework is not a responsible woman. | .46 | |||

| B10. Listening to his wife shames a man. | .62 | |||

| B11. If the children are not well-educated, the mother is the first to be blamed. | .47 | |||

| B12. It is the duty of the wife to actively uphold the husband's authority. | .78 | |||

| B13. A man who does housework is too feminine. | .72 | |||

| B14. The woman who does not behave well should be treated severely. | .84 | |||

| B15. Some women deserve to be beaten. | .83 | |||

| Cronbach α | .75 | .70 | .79 | .71 |

Country and Gender Differences on ASI and GRIM

Table 3 gives the means, and Tables 4 and 5 give the results of MANOVAs for country x gender effects on the ASI and Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage (both mate selection and marriage norms). The overall results show significant main and interaction effects of gender and country on the whole-scale averages (see Table 4). Then, given these results, three separate MANOVAs were conducted, each with its own subscales, one for the ASI (HS, BS), and one for each of the two parts of the GRIM: the mate-selection criteria (four factors) and the gender-role norms in marriage (four factors).

Table 3.

Means (±SDs) by country and gender on ambivalent sexism, mate selection, and gender-role norms in marriage.

| Effect |

ASI |

Mate selection criteria |

Gender-role norms in marriage |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Gender | HS | BS | Provider ability | Consideration and respect | Home-oriented and submissive | Appearance and attractive | Assist and uphold | Success and housework | Family violence | Male dominance and shame |

| Chinese | Male | 3.64±.75 | 3.88±.79 | 2.96±.72 | 3.83±.64 | 3.58±.75 | 3.23±.67 | 4.51±1.00 | 2.91±.89 | 2.91±1.31 | 2.70±.90 |

| Female | 3.09±.79 | 4.36±.72 | 4.03±.52 | 4.06±.49 | 3.51±.67 | 2.91±.66 | 4.89±.80 | 2.63±.81 | 2.32±1.76 | 2.45±.80 | |

| US | Male | 3.24±.79 | 3.35±.79 | 2.76±.57 | 4.36±.44 | 2.36±.87 | 3.78±.61 | 3.30±.93 | 2.95±.83 | 1.27±.49 | 1.84±.66 |

| Female | 2.89±.95 | 3.25±.87 | 3.49±.63 | 4.59±.32 | 2.52±.76 | 3.25±.75 | 3.03±.98 | 2.74±.84 | 1.30±.76 | 1.74±.61 | |

Table 4.

MANOVA on ASI (HS, BS), mate selection (four factors), and gender-role norms (four factors), by gender and country.

| Effect | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | Sig. | Partial eta squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 45.785 | 10 | 690 | .000 | .399 |

| Country | 147.223 | 10 | 690 | .000 | .681 |

| Gender × country | 6.338 | 10 | 690 | .000 | .084 |

Table 5.

Separate MANOVAs on ASI (HS, BS), mate selection (four factors), and gender role norms (four factors), by gender and country, with follow-up simple effects.

| Effect | ASI |

Mate selection |

Gender role norms |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | BS | Provider ability | Consideration and respect | Home-oriented and submissive | Appearance and attractive | Assist and uphold | Success and housework | Family violence | Male dominance and shame | ||

| Main effects | Gender | 20.655*** | 6.198** | 294.863*** | 25.309*** | .730 | 41.781*** | 1.412 | 2.027 | 4.953* | 3.198 |

| Country | 6.156* | 145.757*** | 35.129*** | 126.847*** | 278.343*** | 62.970*** | 340.566*** | 7.353*** | 115.586*** | 105.222*** | |

| 2-Way interaction | Country * Gender | 10.045*** | 18.897*** | 5.385* | .033 | 3.321 | 1.388 | 12.621*** | 4.724* | 6.348* | 2.673 |

| Simple effects | Country (on male level) | 19.208*** | 31.59*** | 5.842* | 103.386*** | .147 | 137.204*** | ||||

| Country (on female level) | 5.661* | 200.284*** | 93.880*** | 453.638*** | 1.636 | 23.946 | |||||

| Gender (on Chinese level) | 67.340*** | 52.623*** | 397.695*** | 24.014*** | 13.519*** | 19.016*** | |||||

| Gender (on US level) | 8.938*** | .709 | 83.450*** | 4.543* | 3.574 | .138 | |||||

All df between groups = l; df of country differences for males (within groups)=356, df of country differences for females (within groups)=427, df of gender differences in China (within groups)=533, df of gender differences in US (within groups)=250. Bold font highlights significant effects

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

The ASI (see Table 5) shows significant main and interaction effects of gender and country overall and the same separately on HS and BS, consistent with previous research (Glick et al. 2000). The Chinese sample scores higher on both HS and BS, as in many developing countries. In both samples, men score higher than women on HS, as is true all over the world, and simple effects analyses show further that this gender gap holds for both the U.S. and China. Men overall score lower than women on BS, but further simple effect analyses indicate significant gender differences within the Chinese sample but not the U.S. sample on BS; as is true in countries with higher sexism scores, Chinese women actually outscore men on BS (accepting the subjective positivity, even if it entails paternalism). U.S. women show the pattern typical in many developed countries of not accepting BS as much, so simple effects show that Chinese and U.S. women differ dramatically on BS, one of the largest effects on the ASI here.

On mate selection criteria, MANOVA (see Table 5) indicates significant gender effects on three of four factors (“Provider ability,” “Consideration and respect,” “Appearance”); significant country effects on all four factors; and a significant interaction effect on “Provider ability.” According to simple effects, all women emphasize “Provider ability,” but especially within China. Women also value “Consideration and respect,” while men give relatively higher scores on “Appearance.” Among the larger effects, Chinese more than U.S. participants value traditional gender roles of (male) “Provider ability” and (mutual) “Home-oriented and submissive,” whereas U.S. more than Chinese participants value (female) “Appearance” and (mutual) “Consideration and respect.” The two “mutual” values deserve comment: Both genders in China prefer a home-oriented mate (with women especially seeking a provider), whereas both genders in the U.S. prefer a considerate mate (with men especially seeking an attractive one). Male provider ability and female appearance fit predicted gender-role preferences.

On power-related gender-role norms in marriage, the MANOVA (see Table 5) indicates large, significant country effects on “Assist and uphold,” “Family violence,” and “Male dominance and shame” (with a much smaller but significant effect on “Success and housework”); Chinese participants accept all of these traditional norms more than U.S. participants do. The only significant gender difference, on accepting “Family violence,” shows men accepting this factor more than women do. However, significant interactions and simple effects qualify these main effects for three of the four factors. For “Assist and uphold,” the large country effect shows that, although all Chinese participants endorse this factor, Chinese women especially do. For “Success and housework,” although differences are small, Chinese men accept this more than Chinese women do. For “Family violence,” the large country effect reflects Chinese male somewhat more than Chinese female acceptance of this norm. A similar pattern occurs for “Male dominance and shame,” although the interaction is not significant.

Effects of HS and BS on GRIM

Finally, we turn to ASI correlations with both parts of the GRIM.

Chinese Sample

Tables 6 and 7 show the regressions with HS and BS predicting Chinese men's and women's mate-selection criteria and marriage norms. We had predicted that BS would operate more strongly in mate selection and HS more strongly in marriage roles. For men's mate selection criteria, as predicted, BS has significant effects on two of four factors: “Consideration and respect” and “Home-oriented and submissive.” Also as predicted, for women, BS has significant effects on three of four factors: the same two as men, plus “Provider ability.” Although not predicted, Men's HS has a significant but small effect only on “Home-oriented and submissive,” while women's HS has no significant effect on any of the mate-selection factors. This supports the primary role of BS in mate selection in the Chinese sample.

Table 6.

Effects of HS and BS on mate-selection criteria (β; Chinese sample).

| Male (N=266) |

Female (N=269) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | BS | HS | BS | |

| Provider ability | –.01 | .10 | –.01 | .34** |

| Consideration and respect | .09 | .29** | –.05 | .23** |

| Home-oriented and submissive | .15** | .29** | .07 | .18** |

| Appearance and interests | .05 | .01 | –.02 | .06 |

Bold font highlights significant effects

p<.01

Table 7.

Effects of HS and BS on gender-role norms on marriage (β; Chinese sample).

| Male (N=266) |

Female (N=268) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | BS | HS | BS | |

| Assist and uphold | .21** | .46** | –.02 | .40** |

| Success and housework | .27** | .04 | .10 | .05 |

| Family violence | .28** | –.01 | .19** | –.06 |

| Male dominance and shame | .20** | .00 | .24** | .09 |

Bold font highlights significant effects

p<.01

Moving to marriage norms (Table 7), where we predicted more HS effects for both men and women; men's HS indeed does have significant effects on all four factors. Women's HS also has significant effects on two of four factors: “Family violence” and “Male dominance and shame.” BS has significant effects for both men and women only on “Assist and uphold.”

Overall, in China, 11 out of 16 predicted effects emerged (BS for mate selection and HS for marriage, separately for men and women). All 11 effects are at least medium-sized Betas of .18 to .46. And out of 16 effects predicted not to be significant, only three were unexpectedly significant.

U.S. Sample

Tables 8 and 9 show the regressions of HS and BS effects on U.S. men's and women's mate selection and marriage norms. U.S. sample sizes were much smaller, so the smaller effects are not always significant, even though the same effect sizes (.15–.25) would have been significant in the Chinese sample. Hence, we discuss both significant effects and those marginal Beta effect sizes over .14, for better comparison to the Chinese sample.

Table 8.

Effects of HS and BS on mate-selection criteria (β; U.S. sample).

| Male (N=92) |

Female (N=160) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | BS | HS | BS | |

| Provider ability | –.01 | .11 | .02 | .46** |

| Consideration and respect | .04 | .09 | –.10 | .04 |

| Home-oriented and submissive | .27* | .17*** | –.05 | .28** |

| Appearance and interests | .14*** | .16*** | .11 | .12 |

Bold font highlights significant effects. Italics indicate marginal effects

p<.05

p<.01

p<.10

Table 9.

Effects of HS and BS on gender role norms in marriage (β; U.S. sample).

| Male (N=92) |

Female (N=160) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | BS | HS | BS | |

| Assist and uphold | .34** | .31** | .18** | .50** |

| Success and housework | .36* | .08 | .31** | .28** |

| Family violence | .17*** | .03 | .34** | .07 |

| Male dominance and shame | .20*** | .16*** | .27** | .31** |

Bold font highlights significant effects. Italics indicate marginal effects

p<.05

p<.01

p<.10

As predicted for mate-selection criteria, men's BS has at least marginal effects on two of four factors (Table 8): “Home-oriented and submissive” and “Appearance.” For women, BS also has marginally significant effects on two of four mate selection criteria: “Provider ability” and “Home-oriented and submissive.” Thus, BS effects on mate selection criteria are slightly fewer and weaker than for the Chinese sample, but in the same direction. Out of eight possible HS coefficients, only one was significant, and for men: “Home-oriented and submissive.” Overall, analyses reveal the predicted pattern of mate selection effects in four of eight predicted BS effects and seven of eight predicted HS non-effects. Because some results are marginal, they must be interpreted with caution.

Turning to marriage norms, as predicted, men's HS has significant or marginal effects on all four factors; women's HS also as predicted has significant effects on all four factors of gender role norms in marriage. Thus, six of eight predicted HS effects emerge significantly, and two more are marginal.

Although not predicted, men's BS has significant effects on “Assist and uphold”; women's BS has significant effects on three of four gender role norms in marriage: “Assist and uphold,” “Success and housework,” and “Male dominance and shame.” These American BS effects on marriage norms were not predicted, but we return to them later.

Culture and Gender Differences in Effects of HS and BS on GRIM

Table 10 summarizes the culture and gender comparisons for the predicted effects of BS on mate selection and HS on marriage norms. Although the means had shown various gender and cultural differences, the ASI-GRIM correlational dynamics seem mostly similar across country and gender. Starting with gender, F tests show significant HS-BS gender differences for regression betas on “Provider ability” (F=8.22, p=.03), “Assist and uphold” (F=7.95, p=.03) and “Family violence”(F=24.02, p=.00). BS mainly predicts mate selection (“Provider ability” for women, as well as lesser effects for both genders on “Home-oriented”), whereas HS mainly predicts marriage norms (“Family violence” and “Assist and uphold”), with the exception that BS also predicts one of women's marriage norms (“Assist and uphold”). U.S. women's BS also predicts other marriage norms; perhaps in a less traditional, more individualist, more developed culture, women expect the softer sexism of BS to extend beyond courtship to marriage. This fits the greater emphasis on romance in U.S. close-relationship ideals (Lee et al., under review).

Table 10.

Gender and cultural differences for effects of HS and BS on GRIM (β).

| Mate selection |

Marriage norms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | American | Chinese | American | |||||

| Men | ||||||||

| HS | Home-oriented | .15 | Home-oriented | .27 | Assist and uphold | .21 | Assist and uphold | .34 |

| Success and housework | .27 | Success and housework | .36 | |||||

| Family violence | .28 | Family violence | .17 | |||||

| Male dominance/shame | .20 | Male dominance/shame | .19 | |||||

| BS | Consideration | .29 | Assist/uphold | .46 | Assist/uphold | .31 | ||

| Home-oriented | .29 | Home-oriented | .17 | |||||

| Attractive | .16 | Male dominance/shame | .16 | |||||

| Women | ||||||||

| HS | Assist and uphold | .24 | ||||||

| Success and housework | .31 | |||||||

| Family violence | .19 | Family violence | .34 | |||||

| Male dominance/shame | .24 | Male dominance/shame | .27 | |||||

| BS | Provider | .34 | Provider | .46 | Assist and uphold | .40 | Assist and uphold | .50 |

| Consideration | .23 | Success and housework | .28 | |||||

| Home-oriented | .18 | Home-oriented | .28 | Male dominance/shame | .31 | |||

Turning to country differences, similar effects of HS and BS occur on mate selection and marriage norms in Chinese and U.S. samples. F tests show no significant country difference except of BS effects on “Consideration and respect” (F=24.93, p=.04). Chinese participants’ BS shows bigger effects on “Consideration and respect” than US sample.

Discussion

The current study explores the influence of ambivalent sexism on power-related gender roles in marriage by analyzing the relationship of hostile and benevolent sexism with power-related mate selection and marriage norms. Our basic position is as follows: Just as for Hostile Sexism, the core of Benevolent Sexism is real “sexism,” because BS is an oppressive “benevolence”; both hostile and benevolent sexism operate in marriages by assigning women a low status in both the society and family. The main mechanism of ambivalent sexism in marriage includes two aspects: (a) enacting male dominance at the beginning of a marriage by mate selection criteria; (b) maintaining male dominance during the marriage by power-related gender-role norms. Ambivalent sexists of both genders endorse these criteria and norms, though sexist men more than sexist women, especially on hostile sexism. Benevolent sexism operates for both genders in mate selection and especially for American women in marriage norms. Hostile sexism operates more in marriage norms, and somewhat more for men. Although their means differ, the Chinese and American samples showed similar dynamics.

Hypotheses

Our first hypothesis was that men's BS would positively relate to mate selection criteria favoring female submissive characteristics, such as being home-oriented and deferential. This was supported by both Chinese and American data emphasizing a docile, traditional role for potential mates, except American men showed this BS effect to a more marginal and smaller degree.

Our second hypothesis was that women's BS would positively relate to mate selection criteria favoring traditional male dominant characteristics such as ability to provide. This was supported by both Chinese and American data emphasizing male provider abilities. Overall, in both the Chinese and the U.S. samples, higher BS men tend to select home-oriented and submissive partners, while women tend to select provider partners who also are traditional. This is consistent with our hypotheses, although we did not anticipate high-BS Chinese women's insistence on mutual consideration.

Our third hypothesis was that HS in particular would positively relate to men's and women's traditional imbalanced gender-role norms in marriage. Consistent with this hypothesis, both Chinese and American high-HS men and women were concerned with marriage norms specifying women's roles: in housework but not in success, assisting and upholding male authority, and supporting male dominance while avoiding male shame. All these results are basically consistent with our third hypothesis.

Country Comparisons

The Chinese and U.S. samples show similar effects of HS and BS, indicating the pan-cultural dynamics of ASI. Chinese participants’ BS shows bigger effects on “Consideration and respect” than does the US sample. This may be due to Chinese traditional marriage values which emphasize “consideration and respect for each other as for a guest,” and other causes that also need be explored. American women show bigger sexism effects (both HS and BS) on marriage norms. Perhaps, when U.S. women diverge from the less-sexist country and gender averages, they endorse the whole set of traditional marriage norms more strongly.

The Chinese and U.S. results overall, however, support the cultural main effects hypothesis more than the cultural interaction hypothesis. That is, the main culture difference is that the Chinese sample has a relatively higher score on the ASI than the U.S. sample. This could be due to China's longer traditional history, which makes it relatively harder to change a cultural tradition, along with its developing status and changing norms. Other main culture differences are Chinese men and women both emphasize traditional marriage values (such as “Provider ability,” “Assist and uphold,” “Family violence,” and “Male dominance and shame”), whereas U.S. participants emphasize “Consideration and respect” with U.S. men emphasizing “Appearance.” Some differences may be due to China's longer traditional history, but others may also due to the different economic level between Chinese and U.S. For example, in China, almost all married women need to work even when they have a child (Ma 1997). In the U.S., some women quit their job to become housewives when they have a child, not an option in China.

Gender Comparisons

The significant HS gender difference is understandable, due to men and women's different self-role identification. HS mainly reflects men's prejudice toward women, and women are typically less sexist toward themselves. Nevertheless, Chinese women's BS has relatively higher score (and stronger effects on provider ability) than men's BS. Due to the superficial benefits of BS for women, many people (especially women in more sexist or less-developed countries) usually think BS is a kind of protection and respect attitude toward women. So women more easily accept BS than HS. And due to the superficial benefits of some traditional marriage norms to women, they also more easily accept “Provider ability,” whereas men focus on appearance (especially U.S.) and even family violence (in China). These results show traditional gender role norms often are more accepted by men than women due to their different role identification and group benefits (Fisman et al. 2006; Gutierres et al. 1999; Sprecher et al. 1994), but women buy into the more subtle versions.

Given the shortage of current research, we can only begin to explore the relationship of ambivalent sexism and power-related ideology in marriage. We hope that the power-related Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage (GRIM) scale will be useful beyond the current studies. However, we have not yet explored this relationship in regard to real marital power. Substantial literatures suggest that what people say (i.e., their expressed ideology) does not always correspond to what they actually do (Ajzen and Fishbein 1977; Fiske 2004). People may profess more egalitarian attitudes than their subsequent behavior would suggest. So, the results here might well underestimate the level of sexism (benevolent or otherwise) in subsequent relationships/marriages. In future studies, researchers may recruit married participants and explore the relationships of ambivalent sexism, power-related ideology in marriage, and real marital power. Moreover, we used survey methods to describe the relationship in the current research; future researchers may use experimental methods to explore the causality more fully.

Acknowledgment

This research was sponsored by Chinese Ministry of Education's Social Science Research Program (08JA630027) for the first author and by Princeton University's research funds for the second author.

Contributor Information

Zhixia Chen, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

Susan T. Fiske, Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA

Tiane L. Lee, Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA

References

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:888–918. [Google Scholar]

- Blood R, Wolfe D. Husbands and wives. Free Press; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg RL, Coleman MT. A theoretical look at the gender balance of power in the American couple. Journal of Family Issues. 1989;10:225–250. doi: 10.1177/019251389010002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein P, Schwartz P. American couples: Money, work, and sex. William Morrow; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bond MH, Smith PB. Cross-cultural social and organizational psychology. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:205–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayfield AA. Employment resources and housework in Canada. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Schmitt DP. Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review. 1993;100:204–232. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZX. An investigation of university students’ love values. Psychology. 1999;7:78–53. (in Chinese). (陈志霞 (1999). 大 学生恋爱价值观的调查分析.心理学, 7, 78–53) [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DH, Straus MA. Marital power, conflict and violence in a nationally representative sample of American couples. In: Straus M, Gelles R, editors. Physical violence in American families. Transaction; Somerset, NJ: 1990. pp. 287–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Family man: Fatherhood, housework and gender equity. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau M-M, Rondeau G. Toward a transnational and cross-culture analysis of family violence: issues and recommendations. Transnational and Cross-culture Research. 2004;10:935–949. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MR. Measuring the physical in physical attractiveness: quasi-experiments on the sociobiology of female facial beauty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:925–935. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review. 2002;109:573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Wood W. The origins of sex differences in human behavior: evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist. 1999;54:408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick PW, Eagly AH, Glick P, Johannesen-Schmidt M, Fiske ST, Blum A, et al. Is traditional gender ideology associated with sex-typed mate preferences? A test in nine nations. Sex Roles. 2006;54:603–614. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Gender differences in effects of physical attractiveness on romantic attraction: a comparison across five research paradigms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:981–993. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Gender differences in mate selection preferences: a test of the parental investment model. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:125–139. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree M. Beyond separate spheres: feminism and family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:866–884. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Social beings: A core motives approach to social psychology. Wiley; Hoboken: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fisman R, Iyengar SS, Kamenica E, Simonson I. Gender differences in mate selection: evidence from speed dating experience. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2006;121:673–697. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie D. Who has the power? The marital struggle. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1971;33:445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Diebold J, Bailey-Werner B, Zhu L. The two faces of Adam: ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:1323–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST. The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:491–492. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST. Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:519–537. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST. An ambivalent alliance: hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications of gender inequality. American Psychologist. 2001;56:109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST, Mladinic A, Saiz JL, Abrams D, Masser B, et al. Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:763–775. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Lameiras M, Fiske ST, Eckes T, Masser B, Volpato C, et al. Bad but bold: ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:713–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, Waite LJ. New families, no families? The transformation of the American home. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf E. International research on family violence. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein TN. Gender ideology and perception of the fairness of the division of household labor: effects on marital quality. Social Forces. 1996;74:1029–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierres SE, Kenrick DT, Partch JJ. Beauty, dominance, and the mating game: contrast effects in self-assessment reflect gender differences in mate selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1126–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Buchtel EE. Personality: the universal and the culturally specific. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:369–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JA, Blumstein P, Schwartz P. Social or evolutionary theories? Some observations on preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Graziano WG, West SG. Dominance, prosocial orientation, and female preferences: do nice guys really finish last? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Kamo Y. Determinants of household division of labor: resources, power, and ideology. Journal of Family Issues. 1988;9:177–200. doi: 10.1177/019251388009002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick DT, Trost MR. A reproductive exchange model of heterosexual relationships: Putting proximate economics in ultimate perspective. In: Hendrick C, editor. Close relationships: Review of personality and social psychology. Vol. 10. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1989. pp. 92–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-Y, Emery C. Marital power, conflict, norm consensus, and marital violence in a nationally representative sample of Korean couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnier RT, Katz EC, Berry MA. Successful resolutions to the career-versus-family conflict. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1991;69:439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kulik L. Marital power relations, resources and gender role ideology: a multivariate model for assessing effects. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1999;30:189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lueptow LB, Guss MB, Hyden C. Sex role ideology, marital status, and happiness. Journal of Family Issues. 1989;10:383–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ma HQ. The reality and countermeasures of Chinese women's obtaining employment. Human Resource Development of China. 1997;6:25–28. (马焕琴(1997).我国妇女就业现状与对策. 中国人力资源开发, 6, 25–28 ) [Google Scholar]

- McDonald GW. Family power: The assessment of a decade of theory and research, 1970–1979. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1980;42:841–854. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman LA, Glick P. The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations. Guilford; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sartin RM, Hansen DJ, Huss MT. Domestic violence treatment response and recidivism: a review and implications for the study of family violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Safilios-Rothschild C. A comparison of power structure and marital satisfaction in urban Greek and French families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1967;29:345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Scanzoni J, Szinovacz M. Family decision-making: A developmental sex role model. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Sullivan Q, Hatfield E. Mate selection preferences: gender differences examined in a national sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:1074–1080. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.6.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Toro-Morn M. A study of men and women from different sides of earth to determine if men are from Mars and women are from Venus in their beliefs about love and romantic relationships. Sex Roles. 2002;46:131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Warner RL, Lee GR, Lee J. Social organization, spousal resources, and marital power: a cross-culture study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte MK. Dating, mating, and marriage. Aldine de Gruyter; Hawthorne, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie JR, Ferree MM, Ratcliff KS. Gender and fairness: marital satisfaction in two-earner couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:577–594. [Google Scholar]

- Xu AQ. Mate selection criteria: 50 years flux and its cause. Sociology Research. 2000;6:18–30. (in Chinese). (徐安琪 (2000).择 偶标准:五十年变迁及其原因分析.社会学研究, 6, 11–30) [Google Scholar]

- Yue GA, Chen H, Zhang YY. Verification of evolutionary hypothesis on human mate selection mechanism in cross-culture context. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2005;37:561–568. (in Chinese). (乐国安,陈浩,张彦彦 (2005),.进化心理学择偶心 理机制假设的跨文化检验—以天津、、BOSTON两地征婚启 事的内容分析为例.心理学报, 37, 561–568) [Google Scholar]